Indiana

| State of Indiana | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||

| Nickname(s): The Hoosier State | |||||

| Motto(s): The Crossroads of America | |||||

| |||||

| Official language | English | ||||

| Spoken languages | English, Spanish, other languages | ||||

| Demonym | Hoosier | ||||

| Capital (and largest city) | Indianapolis | ||||

| Largest metro | Indianapolis metropolitan area | ||||

| Area | |||||

| • Total |

36,418 sq mi (94,321 km2) | ||||

| • Width | 140 miles (225 km) | ||||

| • Length | 270 miles (435 km) | ||||

| • % water | 1.5 | ||||

| • Latitude | 37° 46′ N to 41° 46′ N | ||||

| • Longitude | 84° 47′ W to 88° 6′ W | ||||

| Population | |||||

| • Total | 6,619,680 (2015 est)[1] | ||||

| • Density |

182/sq mi (70.2/km2) Ranked 16th | ||||

| Elevation | |||||

| • Highest point |

Hoosier Hill[2][3] 1,257 ft (383 m) | ||||

| • Mean | 700 ft (210 m) | ||||

| • Lowest point |

Confluence of Ohio River and Wabash River[2][3] 320 ft (97 m) | ||||

| Before statehood | Indiana Territory | ||||

| Admission to Union | December 11, 1816 (19th) | ||||

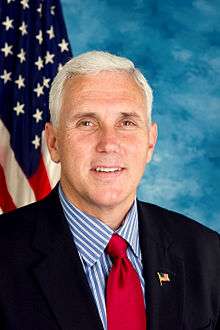

| Governor | Mike Pence (R) | ||||

| Lieutenant Governor | Eric Holcomb (R) | ||||

| Legislature | |||||

| • Upper house | Indiana Senate | ||||

| • Lower house | Indiana House of Representatives | ||||

| U.S. Senators |

Dan Coats (R) Joe Donnelly (D) | ||||

| U.S. House delegation |

7 Republicans, 2 Democrats (list) | ||||

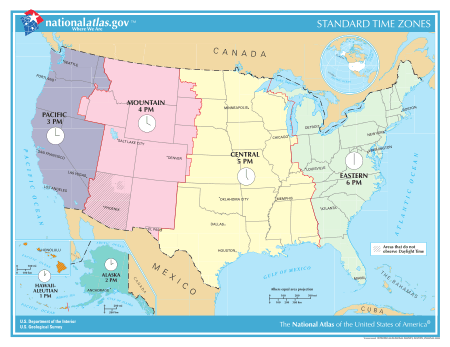

| Time zones |

| ||||

| • 80 counties | Eastern: UTC −5/−4 | ||||

| • 12 counties in Evansville Metro Area, Gary Metro Area For more information, see Time in Indiana | Central: UTC −6/−5 | ||||

| ISO 3166 | US-IN | ||||

| Abbreviations | IN, Ind. | ||||

| Website |

www | ||||

| Indiana state symbols | |

|---|---|

|

The Flag of Indiana | |

|

The Seal of Indiana | |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Cardinal |

| Fish | Largemouth Bass |

| Flower | Peony |

| Tree | Tulip tree |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Water |

| Colors | Blue and gold |

| Firearm | Grouseland Rifle |

| Food | Sugar cream pie |

| Mineral | Coal |

| Motto | The Crossroads of America |

| Poem | "Indiana" |

| Rock | Salem Limestone |

| Ship | USS Indianapolis (4), USS Indiana (4) |

| Soil | Miami |

| Song | official "On the Banks of the Wabash, Far Away" unofficial "Back Home Again in Indiana" |

| Sport | Basketball |

| State route marker | |

| |

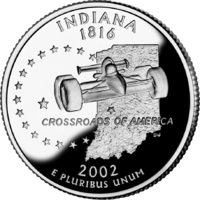

| State quarter | |

|

Released in 2002 | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Indiana ![]() i/ɪndiˈænə/ is a U.S. state located in the midwestern and Great Lakes regions of North America. Indiana is the 38th largest by area and the 16th most populous of the 50 United States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th U.S. state on December 11, 1816.

i/ɪndiˈænə/ is a U.S. state located in the midwestern and Great Lakes regions of North America. Indiana is the 38th largest by area and the 16th most populous of the 50 United States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th U.S. state on December 11, 1816.

Before becoming a territory, varying cultures of indigenous peoples and historic Native Americans inhabited Indiana for thousands of years. Since its founding as a territory, settlement patterns in Indiana have reflected regional cultural segmentation present in the Eastern United States; the state's northernmost tier was settled primarily by people from New England and New York, Central Indiana by migrants from the Mid-Atlantic states and from adjacent Ohio, and Southern Indiana by settlers from the Southern states, particularly Kentucky and Tennessee.[4]

Indiana has a diverse economy with a gross state product of $298 billion in 2012.[5] Indiana has several metropolitan areas with populations greater than 100,000 and a number of smaller industrial cities and towns. Indiana is home to several major sports teams and athletic events including the NFL's Indianapolis Colts, the NBA's Indiana Pacers, the WNBA's Indiana Fever, the Indianapolis 500, and Brickyard 400 motorsports races.

Etymology

The state's name means "Land of the Indians", or simply "Indian Land".[6] It also stems from Indiana's territorial history. On May 7, 1800, the United States Congress passed legislation to divide the Northwest Territory into two areas and named the western section the Indiana Territory. In 1816, when Congress passed an Enabling Act to begin the process of establishing statehood for Indiana, a part of this territorial land became the geographic area for the new state.[7][8][9]

A resident of Indiana is known as a Hoosier. The etymology of this word is disputed, but the leading theory, as advanced by the Indiana Historical Bureau and the Indiana Historical Society, has "Hoosier" originating from Virginia, the Carolinas, and Tennessee (a part of the Upland South region of the United States) as a term for a backwoodsman, a rough countryman, or a country bumpkin.[10][11]

History

Aboriginal inhabitants

The first inhabitants in what is now Indiana were the Paleo-Indians, who arrived about 8000 BC after the melting of the glaciers at the end of the Ice Age. Divided into small groups, the Paleo-Indians were nomads who hunted large game such as mastodons. They created stone tools made out of chert by chipping, knapping and flaking.[12] The Archaic period, which began between 5000 and 4000 BC, covered the next phase of indigenous culture. The people developed new tools as well as techniques to cook food, an important step in civilization. Such new tools included different types of spear points and knives, with various forms of notches. They made ground-stone tools such as stone axes, woodworking tools and grinding stones. During the latter part of the period, they built earthwork mounds and middens, which showed that settlements were becoming more permanent. The Archaic period ended at about 1500 BC, although some Archaic people lived until 700 BC.[12] Afterward, the Woodland period took place in Indiana, where various new cultural attributes appeared. During this period, the people created ceramics and pottery, and extended their cultivation of plants. An early Woodland period group named the Adena people had elegant burial rituals, featuring log tombs beneath earth mounds. In the middle portion of the Woodland period, the Hopewell people began developing long-range trade of goods. Nearing the end of the stage, the people developed highly productive cultivation and adaptation of agriculture, growing such crops as corn and squash. The Woodland period ended around 1000 AD.[12] The Mississippian culture emerged, lasting from 1000 until the 15th century, shortly before the arrival of Europeans. During this stage, the people created large urban settlements designed according to their cosmology, with large mounds and plazas defining ceremonial and public spaces. The concentrated settlements depended on the agricultural surpluses. One such complex was the Angel Mounds. They had large public areas such as plazas and platform mounds, where leaders lived or conducted rituals. Mississippian civilization collapsed in Indiana during the mid-15th century for reasons that remain unclear.[12] The historic Native American tribes in the area at the time of European encounter spoke different languages of the Algonquian family. They included the Shawnee, Miami, and Illini. Later they were joined by refugee tribes from eastern regions including the Delaware who settled in the White and Whitewater River Valleys.

European exploration and sovereignty

In 1679 the French explorer René-Robert Cavelier, Sieur de La Salle was the first European to cross into Indiana after reaching present-day South Bend at the Saint Joseph River.[13] He returned the following year to learn about the region. French-Canadian fur traders soon arrived, bringing blankets, jewelry, tools, whiskey and weapons to trade for skins with the Native Americans. By 1702, Sieur Juchereau established the first trading post near Vincennes. In 1715 Sieur de Vincennes built Fort Miami at Kekionga, now Fort Wayne. In 1717, another Canadian, Picote de Beletre, built Fort Ouiatenon on the Wabash River, to try to control Native American trade routes from Lake Erie to the Mississippi River. In 1732 Sieur de Vincennes built a second fur trading post at Vincennes. French Canadian settlers, who had left the earlier post because of hostilities, returned in larger numbers. In a period of a few years, British colonists arrived from the East and contended against the Canadians for control of the lucrative fur trade. Fighting between the French and British colonists occurred throughout the 1750s as a result.

The Native American tribes of Indiana sided with the French Canadians during the French and Indian War (also known as the Seven Years' War). With British victory in 1763, the French were forced to cede all their lands in North America east of the Mississippi River and north and west of the colonies to the British crown.

The tribes in Indiana did not give up; they destroyed Fort Ouiatenon and Fort Miami during Pontiac's Rebellion. The British royal proclamation of 1763 designated the land west of the Appalachians for Indian use, and excluded British colonists from the area, which the Crown called Indian Territory. In 1775 the American Revolutionary War began as the colonists sought more self-government and independence from the British. The majority of the fighting took place near the East Coast, but the Patriot military officer George Rogers Clark called for an army to help fight the British in the west.[14] Clark's army won significant battles and took over Vincennes and Fort Sackville on February 25, 1779.[15] During the war, Clark managed to cut off British troops, who were attacking the eastern colonists from the west. His success is often credited for changing the course of the American Revolutionary War.[16] At the end of the war, through the Treaty of Paris, the British crown ceded their claims to the land south of the Great Lakes to the newly formed United States, including American Indian lands.

The frontier

In 1787 the US defined present-day Indiana as part of its Northwest Territory. In 1800 Congress separated Ohio from the Northwest Territory, designating the rest of the land as the Indiana Territory.[17] President Thomas Jefferson chose William Henry Harrison as the governor of the territory and Vincennes was established as the capital.[18] After Michigan Territory was separated and the Illinois Territory was formed, Indiana was reduced to its current size and geography.[17]

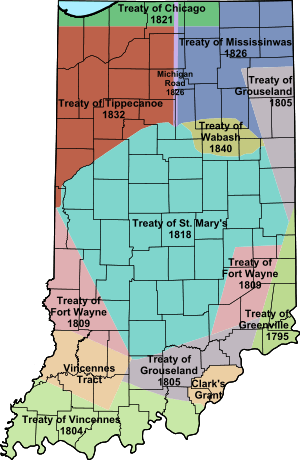

Starting with the Battle of Fallen Timbers in 1794 and Treaty of Greenville, 1795, Indian titles to Indiana lands were extinguished by usurpation, purchase, or war and treaty. About half the state was acquired in the St. Mary's Purchase from the Miami in 1818. Purchases weren't complete until the Treaty of Mississinwas in 1826 acquired the last of the reserved Indian lands in the northeast.

A portrait of the Indiana frontier about 1810: The frontier was defined by the treaty of Fort Wayne in 1809, adding much of southwestern lands around Vincinnes and southeastern lands adjacent to Cincinnati, to areas along the Ohio River as part of U.S. territory. Settlements were military outposts, Fort Ouiatenon in the northwest and Fort Miami (later Fort Wayne) in the northeast, Fort Knox and Vincinnes settlement on the lower Wabash, Clarksville (across from Louisville), Vevay, and Corydon along the Ohio River, the Quaker Colony in Richmond on the eastern border, and Conner's Post (later Connersville) on the east central frontier. Indianapolis wouldn't be a populated place for 15 more years, and central and northern Indiana Territory remained savage wilderness. Indian presence was waning, but still a threat to settlement. Only two counties, Clark and Dearborn in the extreme southeast, had been organized. Land titles issued out of Cincinnati were sparse. Migration was chiefly by flatboat on the Ohio River westerly, and wagon trails up the Wabash/White River Valleys (west) and Whitewater River Valleys (east).

In 1810 the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his brother Tenskwatawa encouraged other tribes in the territory to resist European settlement. Tensions rose and the US authorized Harrison to launch a preemptive expedition against Tecumseh's Confederacy; the US gained victory at the Battle of Tippecanoe on November 7, 1811. Tecumseh was killed in 1813 during the Battle of Thames. After his death, armed resistance to United States control ended in the region. Most Native American tribes in the state were later removed to west of the Mississippi River in the 1820s and 1830s after US negotiations and purchase of their lands.[19]

Statehood and settlement

In order to decrease the threat of Indian raids following the Battle of Tippecanoe, Corydon, a town in the far southern part of Indiana, was named the second capital of the Indiana Territory in May 1813.[17] Two years later, a petition for statehood was approved by the territorial general assembly and sent to Congress. An Enabling Act was passed to provide an election of delegates to write a constitution for Indiana. On June 10, 1816, delegates assembled at Corydon to write the constitution, which was completed in 19 days. President James Madison approved Indiana's admission into the union as the nineteenth state on December 11, 1816.[15] In 1825, the state capital was moved from Corydon to Indianapolis.[17]

Many European immigrants went west to settle in Indiana in the early 19th century. The largest immigrant group to settle in Indiana were Germans, as well as numerous immigrants from Ireland and England. Americans who were primarily ethnically English migrated from the Northern Tier of New York and New England, as well as the mid-Atlantic state of Pennsylvania.[20][21] The arrival of steamboats on the Ohio River in 1811, and the National Road at Richmond in 1829 greatly facilitated settlement of northern and western Indiana.

Following statehood, the new government worked to transform Indiana from a frontier into a developed, well-populated, and thriving state, beginning significant demographic and economic changes. The state's founders initiated a program, Indiana Mammoth Internal Improvement Act, that led to the construction of roads, canals, railroads and state-funded public schools. The plans bankrupted the state and were a financial disaster, but increased land and produce value more than fourfold.[22] In response to the crisis and in order to avert another, in 1851, a second constitution was adopted. Among its provisions were a prohibition on public debt and extension of suffrage to African-Americans.

Civil War

During the American Civil War, Indiana became politically influential and played an important role in the affairs of the nation. As the first western state to mobilize for the United States in the war, Indiana had soldiers participating in all of the major engagements. The state provided 126 infantry regiments, 26 batteries of artillery and 13 regiments of cavalry to the cause of the Union.[23] In 1861 Indiana was assigned a quota of 7,500 men to join the Union Army.[24] So many volunteered in the first call that thousands had to be turned away. Before the war ended, Indiana contributed 208,367 men to fight and serve in the war. Casualties were over 35% among these men: 24,416 lost their lives in the conflict and over 50,000 more were wounded.[25] The only Civil War battle fought in Indiana was the Battle of Corydon, which occurred during Morgan's Raid. The battle left 15 dead, 40 wounded, and 355 captured.[26]

Indiana remained a largely agricultural state; post-war industries included food processing, such as milling grain, distilling it into alcohol, and meatpacking; building of wagons, buggies, farm machinery, and hardware.

Early 20th century

With the onset of the industrial revolution, Indiana industry began to grow at an accelerated rate across the northern part of the state. With industrialization, workers developed labor unions and suffrage movements arose in relation to the progress of women.[27] The Indiana Gas Boom led to rapid industrialization during the late 19th century by providing cheap fuel to the region.[28] In the early 20th century, Indiana developed into a strong manufacturing state with ties to the new auto industry.[20] Haynes-Apperson, the nation's first commercially successful auto company, operated in Kokomo until 1925. The construction of the Indianapolis Motor Speedway and the start of auto-related industries were also related to the auto industry boom.[29]

During the 1930s, Indiana, like the rest of the nation, was affected by the Great Depression. The economic downturn had a wide-ranging negative impact on Indiana, such as the decline of urbanization. The Dust Bowl further to the west resulted in many migrants fleeing into the more industrialized Midwest. Governor Paul V. McNutt's administration struggled to build a state-funded welfare system to help the overwhelmed private charities. During his administration, spending and taxes were both cut drastically in response to the Depression, and the state government was completely reorganized. McNutt ended Prohibition in the state and enacted the state's first income tax. On several occasions, he declared martial law to put an end to worker strikes.[30] World War II helped lift the economy in Indiana, as the war required steel, food and other goods that were produced in the state.[31] Roughly 10 percent of Indiana's population joined the armed forces, while hundreds of industries earned war production contracts and began making war material.[32] Indiana manufactured 4.5 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking eighth among the 48 states.[33] The expansion of industry to meet war demands helped end the Great Depression.[31]

Modern era

With the conclusion of World War II, Indiana rebounded to levels of production before the Great Depression. Industry became the primary employer, a trend that continued into the 1960s. Urbanization during the 1950s and 1960s led to substantial growth in the state's cities. The auto, steel and pharmaceutical industries topped Indiana's major businesses. Indiana's population continued to grow during the years after the war, exceeding five million by the 1970 census.[34] In the 1960s the administration of Matthew E. Welsh adopted its first sales tax of two percent.[35] Indiana schools were desegregated in 1949. In 1950, the Census Bureau reported Indiana's population as 95.5% white and 4.4% black.[36] Governor Welsh also worked with the General Assembly to pass the Indiana Civil Rights Bill, granting equal protection to minorities in seeking employment.[37]

Beginning in 1970, a series of amendments to the state constitution were proposed. With adoption, the Indiana Court of Appeals was created and the procedure of appointing justices on the courts was adjusted.[38]

The 1973 oil crisis created a recession that hurt the automotive industry in Indiana. Companies such as Delco Electronics and Delphi began a long series of downsizing that contributed to high unemployment rates in manufacturing in Anderson, Muncie, and Kokomo. The restructuring and deindustrialization trend continued until the 1980s, when the national and state economy began to diversify and recover.[39]

Geography

With a total area (land and water) of 36,418 square miles (94,320 km2), Indiana ranks as the 38th largest state in size.[40] The state has a maximum dimension north to south of 250 miles (400 km) and a maximum east to west dimension of 145 miles (233 km).[41] The state's geographic center (39° 53.7'N, 86° 16.0W) is in Marion County.[42]

Located in the midwestern United States, Indiana is one of eight states that make up the Great Lakes Region.[43] Indiana is bordered on the north by Michigan, on the east by Ohio, and on the west by Illinois,[44] while Lake Michigan borders Indiana on the northwest and the Ohio River separates Indiana from Kentucky on the south.[42][45]

The average altitude of Indiana is about 760 feet (230 m) above sea level.[46] The highest point in the state is Hoosier Hill in Wayne County at 1,257 feet (383 m) above sea level.[40][47] The lowest point at 320 feet (98 m) above sea level is located in Posey County, where the Wabash River flows into the Ohio River.[40][42] Only 2,850 square miles (7,400 km2) have an altitude greater than 1,000 feet (300 m) and this area is enclosed within 14 counties. About 4,700 square miles (12,000 km2) have an elevation of less than 500 feet (150 m), mostly concentrated along the Ohio and lower Wabash Valleys, concentrated from Tell City and Terre Haute to Evansville and Mount Vernon.[48]

The state includes two natural regions of the United States, the Central Lowlands and the Interior Low Plateaus.[49] The till plains make up the northern and central allotment of Indiana. Much of its appearance is a result of elements left behind by glaciers. Central Indiana is mainly flat with some low rolling hills (except where rivers cut deep valleys through the plain, like at the Wabash River and Sugar Creek) and soil composed of glacial sands, gravel and clay, which results in exceptional farmland.[44] Northern Indiana is also very similar except for the presence of higher and hillier terminal moraines and many kettle lakes in some regions. In northwest Indiana there are various sand ridges and dunes, some reaching nearly 200 feet in height. These are located along the Lake Michigan shoreline and also inland to the Kankakee River Valley. The unglaciated southern segment of the state carries a different and off-balance surface, characterized in places by profound valleys and rugged, hilly terrain much different from the rest of the state. Here, bedrock is exposed at the surface and isn't buried in glacial till like further north. Because of the prevalent limestone, there are numerous caves in the area. The soil is fertile in the valleys of southern Indiana.

Hydrology

Major river systems in Indiana include the Whitewater, White, Blue, Wabash, St. Joseph, and Maumee rivers.[50] According to the Indiana Department of Natural Resources, in 2007 there were 65 rivers, streams, and creeks of environmental interest or scenic beauty, which included only a portion of an estimated 24,000 total river miles within the state.[51]

The Ohio River forms Indiana's southern border with Kentucky. The major cities of New Albany and Evansville are located on the river.

The Wabash River, which is the longest free-flowing river east of the Mississippi River, is the official river of Indiana.[52][53] At 475 miles (764 km) in length, the river bisects the state from northeast to southwest before flowing south, mostly along the Indiana-Illinois border. The river has been the subject of several songs, such as On the Banks of the Wabash, The Wabash Cannonball and Back Home Again, In Indiana.[54][55]

There are about 900 lakes listed by the Indiana Department of Natural Resources.[56] To the northwest, Indiana borders Lake Michigan, where the Port of Indiana operates the state's largest shipping port. Tippecanoe Lake, the deepest lake in the state, reaches depths at nearly 120 feet (37 m), while Lake Wawasee is the largest natural lake in Indiana.[57] At 10,750 acres (summer pool level), Lake Monroe is the largest lake in Indiana.

Climate

Indiana has a humid continental climate, with cold winters and warm, wet summers.[58] The extreme southern portion of the state is within the humid subtropical climate area and receives more precipitation than other parts of Indiana.[44] Temperatures generally diverge from the north and south sections of the state. In the middle of the winter, average high/low temperatures range from around 30 °F/15 °F (−1 °C/-10 °C) in the far north to 39 °F/22 °F (4 °C/-6 °C) in the far south.[59]

In the middle of summer there is generally a little less variation across the state, as average high/low temperatures range from around 84 °F/64 °F (29 °C/18 °C) in the far north to 90 °F/69 °F (32 °C/21 °C) in the far south.[59] The record high temperature for the state was 116 °F (47 °C) set on July 14, 1936 at Collegeville. The record low was −36 °F (−38 °C) on January 19, 1994 at New Whiteland. The growing season typically spans from 155 days in the north to 185 days in the south.

While droughts occasionally occur in the state, rainfall totals are distributed relatively equally throughout the year. Precipitation totals range from 35 inches (89 cm) near Lake Michigan in northwest Indiana to 45 inches (110 cm) along the Ohio River in the south, while the state's average is 40 inches (100 cm). Annual snowfall in Indiana varies widely across the state, ranging from 80 inches (200 cm) in the northwest along Lake Michigan to 14 inches (36 cm) in the far south. Lake effect snow accounts for roughly half of the snowfall in northwest and north central Indiana due to the effects of the moisture and relative warmth of Lake Michigan upwind. The mean wind speed is 8 miles per hour (13 km/h).[60]

In a 2012 report, Indiana was ranked eighth in a list of the top 20 tornado-prone states based on National Weather Service data from 1950 through 2011.[61] A 2011 report ranked South Bend 15th among the top 20 tornado-prone cities in the United States,[62] while another report from 2011 ranked Indianapolis eighth.[63][64][65] Despite its vulnerability, Indiana is not a part of tornado alley.[66]

| Average Precipitation in Indiana[67] | ||||||||||||

| Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Annum |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.48 | 2.27 | 3.36 | 3.89 | 4.46 | 4.19 | 4.22 | 3.91 | 3.12 | 3.02 | 3.44 | 3.13 | 41.49 |

| Location | July (°F) | July (°C) | January (°F) | January (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indianapolis | 85/66 | 29/19 | 35/20 | 2/–6 |

| Fort Wayne | 84/62 | 29/17 | 32/17 | 0/–8 |

| Evansville | 88/67 | 31/19 | 41/24 | 5/–4 |

| South Bend | 83/63 | 28/17 | 32/18 | 0/–8 |

| Bloomington | 87/65 | 30/18 | 39/21 | 4/–6 |

| Lafayette | 84/62 | 29/17 | 31/14 | –0/–10 |

| Muncie | 85/64 | 29/18 | 34/19 | 1/–7 |

Time zones

Indiana is one of thirteen U.S. states that are divided into more than one time zone. Indiana's time zones have fluctuated over the past century. At present most of the state observes Eastern Time; six counties near Chicago and six near Evansville observe Central Time. Debate continues on the matter.

Before 2006, most of Indiana did not observe daylight saving time (DST). Some counties within this area, particularly Floyd, Clark, and Harrison counties near Louisville, Kentucky, and Ohio and Dearborn counties near Cincinnati, Ohio, unofficially observed DST by local custom. Since April 2006 the entire state observes DST.

Indiana counties and statistical areas

Indiana is divided into 92 counties. As of 2010, the state includes 16 metropolitan and 25 micropolitan statistical areas, 117 incorporated cities, 450 towns, and several other smaller divisions and statistical areas.[69][70] Marion County and Indianapolis have a consolidated city-county government.[69]

Major cities

Indianapolis is the capital of Indiana and its largest city.[69][71] Indiana's four largest metropolitan areas are Indianapolis, Fort Wayne, Evansville, and South Bend.[72] The table below lists the ten largest municipalities in the state based on the 2014 United States Census Estimate.[73]

| Largest cities or towns in Indiana 2014 United States Census Bureau Estimate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Name | County | Pop. | ||||||

| Indianapolis  Fort Wayne |

1 | Indianapolis | Marion | 848,788 |  Evansville  South Bend | ||||

| 2 | Fort Wayne | Allen | 258,522 | ||||||

| 3 | Evansville | Vanderburgh | 120,346 | ||||||

| 4 | South Bend | St. Joseph | 101,190 | ||||||

| 5 | Carmel | Hamilton | 86,682 | ||||||

| 6 | Fishers | Hamilton | 86,325 | ||||||

| 7 | Bloomington | Monroe | 83,565 | ||||||

| 8 | Hammond | Lake | 78,384 | ||||||

| 9 | Gary | Lake | 77,909 | ||||||

| 10 | Lafayette | Tippecanoe | 70,654 | ||||||

Demographics

Population

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1800 | 2,632 | — | |

| 1810 | 24,520 | 831.6% | |

| 1820 | 147,178 | 500.2% | |

| 1830 | 343,031 | 133.1% | |

| 1840 | 685,866 | 99.9% | |

| 1850 | 988,416 | 44.1% | |

| 1860 | 1,350,428 | 36.6% | |

| 1870 | 1,680,637 | 24.5% | |

| 1880 | 1,978,301 | 17.7% | |

| 1890 | 2,192,404 | 10.8% | |

| 1900 | 2,516,462 | 14.8% | |

| 1910 | 2,700,876 | 7.3% | |

| 1920 | 2,930,390 | 8.5% | |

| 1930 | 3,238,503 | 10.5% | |

| 1940 | 3,427,796 | 5.8% | |

| 1950 | 3,934,224 | 14.8% | |

| 1960 | 4,662,498 | 18.5% | |

| 1970 | 5,193,669 | 11.4% | |

| 1980 | 5,490,224 | 5.7% | |

| 1990 | 5,544,159 | 1.0% | |

| 2000 | 6,080,485 | 9.7% | |

| 2010 | 6,483,802 | 6.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 6,619,680 | 2.1% | |

| Source: 1910–2010[74] 2015 estimate[1] | |||

The United States Census Bureau estimates that the population of Indiana was 6,619,680 on July 1, 2015, a 2.10% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[1]

The state's population density was 181.0 persons per square mile, the 16th highest in the United States.[69] As of the 2010 U.S. Census, Indiana's population center is located northwest of Sheridan, in Hamilton County (+40.149246, -086.259514).[69][75][76]

In 2005, 77.7% of Indiana residents lived in metropolitan counties, 16.5% lived in micropolitan counties and 5.9% lived in non-core counties.[77]

Race and ethnicity

The racial makeup of the state (based on the 2011 population estimate) was:

- 86.8% White American (81.3% non-Hispanic white)

- 9.4% Black or African American

- 1.7% Asian

- 1.7% biracial or multi-racial

- 0.4% Native American

- 0.1% Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islanders.[78]

Hispanic or Latino of any race made up 6.2% of the population.[78] The Hispanic population is Indiana's fastest-growing ethnic minority.[79] 28.2% of Indiana's children under the age of 1 belonged to minority groups (note: children born to white hispanics are counted as minority group).[80]

| Racial composition | 1990[81] | 2000[82] | 2010[83] |

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 90.6% | 87.5% | 84.3% |

| Black | 7.8% | 8.4% | 9.1% |

| Asian | 0.7% | 1.0% | 1.6% |

| Native | 0.2% | 0.3% | 0.3% |

| Native Hawaiian and other Pacific Islander | - | - | - |

| Other race | 0.7% | 1.6% | 2.7% |

| Two or more races | - | 1.2% | 2.0% |

Age and gender

Based on population estimates for 2011, 6.6% of the state's population is under the age of five, 24.5% is under the age of 18, and 13.2% is 65 years of age or older.[78] From the 2010 U.S. Census demographic data for Indiana, the median age is 37.0 years.[84]

Ancestry

German is the largest ancestry reported in Indiana, with 22.7% of the population reporting that ancestry in the Census. Persons citing American (12.0%) and English ancestry (8.9%) are also numerous, as are Irish (10.8%) and Polish (3.0%).[85] Most of those citing American ancestry are actually of English descent, but have family that has been in North America for so long, in many cases since the early colonial era, that they identify simply as American.[86][87][88][89] In the 1980 census 1,776,144 people claimed German ancestry, 1,356,135 claimed English ancestry and 1,017,944 claimed Irish ancestry out of a total population of 4,241,975 making the state 42% German, 32% English and 24% Irish.[90]

Population growth and decline

Population growth since 1990 has been concentrated in the counties surrounding Indianapolis, with four of the top five fastest-growing counties in that area: Hamilton, Hendricks, Johnson, and Hancock. The other county is Dearborn County, which is near Cincinnati, Ohio. Hamilton County has also been the fastest-growing county in the area consisting of Indiana and its bordering states of Illinois, Michigan, Ohio and Kentucky, and is the 20th fastest-growing county in the country.[91]

Cities and towns

With a population of 829,817, Indianapolis is the largest city in Indiana and 12th largest in the United States, according to the 2010 Census. Three other cities in Indiana have a population greater than 100,000: Fort Wayne (253,617), Evansville (117,429) and South Bend (101,168).[92] Since 2000, Fishers has seen the largest population rise amongst the state's 20 largest cities with an increase of 100 percent.[93]

Hammond and Gary have seen the largest population declines regarding the top 20 largest cities since 2000, with a decrease of 6.8 and 21.0 percent respectively.[93] Other cities that have seen extensive growth since 2000 are Noblesville (39.4 percent), Greenwood (81 percent), Carmel (21.4 percent) and Lawrence (9.3 percent). Meanwhile, Evansville (−4.2 percent), Anderson (−4 percent) and Muncie (−3.9 percent) are cities that have seen the steepest decline in population in the state.[94]

Indianapolis has largest population of the state's metropolitan areas and 33rd largest in the country.[95] The Indianapolis metropolitan area encompasses Marion County and nine surrounding counties in central Indiana.

Median household income in Indiana

As of the 2010 U.S. Census, Indiana's median household income was $44,616, ranking it 36th among the United States and the District of Columbia.[97] In 2005, the median household income for Indiana residents was $43,993. Nearly 498,700 Indiana households had incomes from $50,000 to $74,999, accounting for 20% of all households.[98]

Hamilton County's median household income is nearly $35,000 higher than the Indiana average. At $78,932, it ranks seventh in the country among counties with less than 250,000 people. The next highest median incomes in Indiana are also found in the Indianapolis suburbs; Hendricks County has a median of $57,538, followed by Johnson County at $56,251.[98]

Religion

| Affiliation | % of Indiana population | |

|---|---|---|

| Christianity | 80 | |

| Evangelical Protestant | 34 | |

| Mainline Protestant | 22 | |

| Catholic | 18 | |

| Black Protestant | 6 | |

| Mormon | 1 | |

| Jehovah's Witnesses | 1 | |

| Orthodox | 0.5 | |

| Other Christianity | 0.5 | |

| Judaism | 1 | |

| Buddhism | 0.5 | |

| Islam | 0.5 | |

| Hinduism | 0.5 | |

| Other Faiths | 1 | |

| Unaffiliated | 16 | |

| Don't Know/No Answer | 0.5 | |

| Total | 100 | |

Although the largest single religious denomination in the state is Catholic (747,706 members), most of the population are members of various Protestant denominations. The largest Protestant denomination by number of adherents in 2010 was the United Methodist Church with 355,043.[100] A study by the Graduate Center found that 20 percent are Roman Catholic, 14 percent belong to different Baptist churches, 10 percent are other Christians, nine percent are Methodist, and six percent are Lutheran. The study found that 16% of Indiana is affiliated with no religion.[101]

Indiana is home to the St. Meinrad Archabbey, one of two Catholic archabbeys in the United States and one of 11 in the world. The Lutheran Church–Missouri Synod has one of its two seminaries in Fort Wayne. Two conservative denominations, the Free Methodist Church and the Wesleyan Church, have their headquarters in Indianapolis as does the Christian Church.[102][103]

The Fellowship of Grace Brethren Churches maintains offices and publishing work in Winona Lake.[104] Huntington serves as the home to the Church of the United Brethren in Christ.[105] Anderson is home to the headquarters of the Church of God.[106] The headquarters of the Missionary Church is located in Fort Wayne.[107]

The Friends United Meeting of the Religious Society of Friends, the largest branch of American Quakerism, is based in Richmond,[108] which also houses the oldest Quaker seminary in the United States, the Earlham School of Religion.[109] The Islamic Society of North America is headquartered in Plainfield.[110]

Language

Spanish is the second-most-spoken language in Indiana, after English .

Law and government

Indiana has a constitutional democratic republican form of government with three branches: the executive, including an elected governor and lieutenant governor; the legislative, consisting of an elected two-house General Assembly; and the judicial, the Supreme Court of Indiana, the Indiana Court of Appeals and circuit courts.

The Governor of Indiana serves as the chief executive of the state and has the authority to manage the government as established in the Constitution of Indiana. The governor and the lieutenant governor are jointly elected to four-year terms, with gubernatorial elections running concurrent with United States presidential elections (1996, 2000, 2004, 2008, etc.).[111] The governor may not serve more than two consecutive terms.[111] The governor works with the Indiana General Assembly and the Supreme Court of Indiana to govern the state and has the authority to adjust the other branches. Special sessions of the General Assembly can be called upon by the governor as well as have the power to select and remove leaders of nearly all state departments, boards and commissions. Other notable powers include calling out the Indiana Guard Reserve or the Indiana National Guard in times of emergency or disaster, issuing pardons or commuting the sentence of any criminal offenders except in cases of treason or impeachment and possessing an abundant amount of statutory authority.[111][112][113] The lieutenant governor serves as the President of the Senate and is responsible for ensuring that the senate rules are acted in accordance with by its constituents. The lieutenant governor can only vote to break ties. If the governor dies in office, becomes permanently incapacitated, resigns or is impeached, the lieutenant governor becomes governor. If both the governor and lieutenant governor positions are unoccupied, the Senate President pro tempore becomes governor.[114]

The Indiana General Assembly is composed of a 50-member Senate and 100-member House of Representatives. The Senate is the upper house of the General Assembly and the House of Representatives is the lower house.[111] The General Assembly has exclusive legislative authority within the state government. Both the Senate and House of Representatives can introduce legislation, with the exception that the Senate is not authorized to initiate legislation that will affect revenue. Bills are debated and passed separately in each house, but must be passed by both houses before they can be submitted to the Governor.[115] The legislature can nullify a veto from the governor with a majority vote of full membership in the Senate and House of Representatives.[111] Each law passed by the General Assembly must be used without exception to the entire state. The General Assembly has no authority to create legislation that targets only a particular community.[115][116] The General Assembly can manage the state's judiciary system by arranging the size of the courts and the bounds of their districts. It also can oversee the activities of the executive branch of the state government, has restricted power to regulate the county governments within the state, and has exclusive power to initiate the method to alter the Indiana Constitution.[115][117]

The Indiana Supreme Court is made up of five judges with a Court of Appeals composed of 15 judges. The governor selects judges for the supreme and appeal courts from a group of applicants chosen by a special commission. After serving for two years, the judges must acquire the support of the electorate to serve for a 10-year term.[111] In nearly all cases, the Supreme Court does not have original jurisdiction and can only hear cases that are petitioned to the court following being heard in lower courts. Local circuit courts are where the majority of cases begin with a trial and the consequence decided by the jury. The Supreme Court does have original and sole jurisdiction in certain specific areas including the practice of law, discipline or disbarment of Judges appointed to the lower state courts, and supervision over the exercise of jurisdiction by the other lower courts of the State.[118][119]

The state is divided into 92 counties, which are led by a board of county commissioners. 90 counties in Indiana have their own circuit court with a judge elected for a six-year term. The remaining two counties, Dearborn and Ohio, are combined into one circuit. Many counties operate superior courts in addition to the circuit court. In densely populated counties where the caseload is traditionally greater, separate courts have been established to solely hear either juvenile, criminal, probate or small claims cases. The establishment, frequency and jurisdiction of these additional courts varies greatly from county to county. There are 85 city and town courts in Indiana municipalities, created by local ordinance, typically handling minor offenses and not considered courts of record. County officials that are elected to four-year terms include an auditor, recorder, treasurer, sheriff, coroner and clerk of the circuit court. All incorporated cities in Indiana have a mayor and council form of municipal government. Towns are governed by a town council and townships are governed by a township trustee and advisory board.[111][120]

Politics

From 1880 to 1924, a resident of Indiana was included in all but one presidential election. Indiana Representative William Hayden English was nominated for Vice-President and ran with Winfield Scott Hancock in the 1880 election.[121] In 1884 former Indiana Governor Thomas A. Hendricks was elected Vice-President of the United States. He served until his death on November 25, 1885, under President Grover Cleveland.[122] In 1888 Indiana Senator Benjamin Harrison was elected President of the United States and served one term. He remains the only U.S. President from Indiana. Indiana Senator Charles W. Fairbanks was elected Vice-President in 1904, serving under President Theodore Roosevelt until 1909.[123] Fairbanks made another run for Vice-President with Charles Evans Hughes in 1916, but they both lost to Woodrow Wilson and Indiana Governor Thomas R. Marshall, who served as Vice-President from 1913 until 1921.[124] Not until 1988 did another presidential election involve a native of Indiana, when Senator Dan Quayle was elected Vice-President and served one term with George H. W. Bush.[44] Governor Mike Pence was elected Vice-President in 2016, to serve with Donald Trump.

Indiana has long been considered to be a Republican stronghold,[125][126] particularly in Presidential races, but the Cook Partisan Voting Index (CPVI) now rates Indiana as only R+5, a smaller Republican edge than is assigned to 20 of the 28 "red" states. Indiana was one of only ten states to support Republican Wendell Willkie in 1940.[44] On 14 occasions has the Republican candidate defeated the Democrat by a double digit margin in the state, including six times where a Republican won the state by more than 20%.[127] In 2000 and 2004 George W. Bush won the state by a wide margin while the election was much closer overall. The state has only supported a Democrat for president five times since 1900. In 1912, Woodrow Wilson became the first Democrat to win the state with 43% of the vote. Twenty years later, Franklin D. Roosevelt won the state with 55% of the vote over incumbent Republican Herbert Hoover. Roosevelt won the state again in 1936. In 1964, 56% of voters supported Democrat Lyndon B. Johnson over Republican Barry Goldwater. Forty-four years later, Democrat Barack Obama narrowly won the state against John McCain 50% to 49%.[128] In the following election, Republican Mitt Romney won back the state for the Republican party with 54% of the vote over incumbent Obama who won 43%.[129]

While only five Democratic presidential nominees have carried Indiana since 1900, 11 Democrats were elected governor during that time. Before Mitch Daniels became governor in 2005, Democrats had held the office for 16 consecutive years. Indiana elects two senators and nine representatives to Congress. The state has 11 electoral votes in presidential elections.[127] Seven of the districts favor the Republican Party according to the CPVI rankings; there are currently seven Republicans serving as representatives and two Democrats. Historically, Republicans have been strongest in the eastern and central portions of the state, while Democrats have been strongest in the northwestern part of the state. Occasionally, certain counties in the southern part of the state will vote Democratic. Marion County, Indiana's most populous county, supported the Republican candidates from 1968 to 2000, before backing the Democrats in the 2004, 2008, and 2012, elections. Indiana's second most populous county, Lake County, strongly supports the Democratic party and has not voted for a Republican since 1972.[127] In 2005, the Bay Area Center for Voting Research rated the most liberal and conservative cities in the United States on voting statistics in the 2004 presidential election, based on 237 cities with populations of more than 100,000. Five Indiana cities were mentioned in the study. On the liberal side, Gary was ranked second and South Bend came in at 83. Among conservative cities, Fort Wayne was 44th, Evansville was 60th and Indianapolis was 82nd on the list.[130]

Military installations

Indiana is home to several current and former military installations. The largest of these is the Naval Surface Warfare Center Crane Division, located approximately 25 miles southwest of Bloomington, which is the third largest naval installation in the world, comprising approximately 108 square miles of territory.

Other active installations include Air National Guard fighter units at Fort Wayne, and Terre Haute airports (to be consolidated at Fort Wayne under the 2005 BRAC proposal, with the Terre Haute facility remaining open as a non-flying installation). The Army National Guard conducts operations at Camp Atterbury in Edinburgh, Indiana, helicopter operations out of Shelbyville Airport and urban training at Muscatatuck Urban Training Center. The Army's Newport Chemical Depot, which is now closed and turning into a coal purifier plant. Also, Naval Operational Support Center Indianapolis is home to several Navy Reserve units, two Marine Reserve units, and a small contingent of active and full-time-support reserve personnel.

Indiana was formerly home to two major military installations; Grissom Air Force Base near Peru (realigned to an Air Force Reserve installation in 1994) and Fort Benjamin Harrison near Indianapolis, now closed, though the Department of Defense continues to operate a large finance center there (Defense Finance and Accounting Service).

Economy

| Top publicly traded companies in Indiana for 2014 according to revenues with State and U.S. rankings | |||||

| State | Corporation | US | |||

| 1 | Anthem Inc. | 38 | |||

| 2 | Eli Lilly and Company | 129 | |||

| 3 | Cummins Inc. | 168 | |||

| 4 | Steel Dynamics | 355 | |||

| 5 | NiSource | 448 | |||

| 6 | Calumet Lubricants | 467 | |||

| 7 | Simon Property Group | 479 | |||

| 8 | Berry Plastics | 528 | |||

| 9 | Zimmer Holdings | 531 | |||

| 10 | CNO Financial Group | 548 | |||

| 11 | Thor Industries | 636 | |||

| 12 | LVB Acquisition | 719 | |||

| 13 | Republic Airways Holdings | 819 | |||

| 14 | Vectren | 842 | |||

| 15 | hhgregg | 845 | |||

| 16 | Springleaf Financial | 886 | |||

| 17 | KAR Auction Services | 918 | |||

| 18 | Allison Transmission | 996 | |||

|

Source: Fortune[131] | |||||

In 2000 Indiana had a work force of 3,084,100.[132] The total gross state product in 2010 was $275.7 billion.[133] A high percentage of Indiana's income is from manufacturing.[134] The Calumet region of northwest Indiana is the largest steel producing area in the U.S. Indiana's other manufactures include pharmaceuticals and medical devices, automobiles, electrical equipment, transportation equipment, chemical products, rubber, petroleum and coal products, and factory machinery.

Despite its reliance on manufacturing, Indiana has been much less affected by declines in traditional Rust Belt manufactures than many of its neighbors. The explanation appears to be certain factors in the labor market. First, much of the heavy manufacturing, such as industrial machinery and steel, requires highly skilled labor, and firms are often willing to locate where hard-to-train skills already exist. Second, Indiana's labor force is located primarily in medium-sized and smaller cities rather than in very large and expensive metropolises. This makes it possible for firms to offer somewhat lower wages for these skills than would normally be paid. Firms often see in Indiana a chance to obtain higher than average skills at lower than average wages.[135]

Indiana is home to the international headquarters and research facilities of pharmaceutical company Eli Lilly in Indianapolis, the state's largest corporation, as well as the world headquarters of Mead Johnson Nutritionals in Evansville.[136] Overall, Indiana ranks fifth among all U.S. states in total sales and shipments of pharmaceutical products and second highest in the number of biopharmaceutical related jobs.[137]

Indiana is located within the U.S. Corn Belt and Grain Belt. The state has a feedlot-style system raising corn to fatten hogs and cattle. Along with corn, soybeans are also a major cash crop. Its proximity to large urban centers, such as Indianapolis and Chicago, assure that dairying, egg production, and specialty horticulture occur. Other crops include melons, tomatoes, grapes, mint, popping corn, and tobacco in the southern counties.[138] Most of the original land was not prairie and had to be cleared of deciduous trees. Many parcels of woodland remain and support a furniture-making sector in the southern portion of the state.

In 2011 Indiana was ranked first in the Midwest and sixth in the country for best places to do business according to CEO magazine.[139]

State budget

Indiana does not have a legal requirement to balance the state budget either in law or its constitution. Instead, Indiana has a constitutional ban on assuming debt. Indiana has a Rainy Day Fund and for healthy reserves proportional to spending. Indiana is one of the few states in the U.S. which do not allow a line-item veto.

Indiana has a flat state income tax rate of 3.4%. Many Indiana counties also collect income tax. The state sales tax rate is 7% with exemptions for food, prescription medications and over-the-counter medications.[140] In some jurisdictions an additional Food and Beverage Tax is charged, at a rate of 1% (Marion County's rate is 2%), on sales of prepared meals and beverages.[141]

Property taxes are imposed on both real and personal property in Indiana and are administered by the Department of Local Government Finance. Property is subject to taxation by a variety of taxing units (schools, counties, townships, cities and towns, libraries), making the total tax rate the sum of the tax rates imposed by all taxing units in which a property is located. However, a "circuit breaker" law enacted on March 19, 2008 limits property taxes to one percent of assessed value for homeowners, two percent for rental properties and farmland and three percent for businesses.

In Fiscal year 2011 Indiana reported one of the largest surpluses among U.S states, with an extra $1.2 billion in its accounts. Gov. Mitch Daniels, a Republican, authorized bonus payments of up to $1,000 for state employees on Friday, July 15, 2011. An employee who "meets expectations" will get $500, those who "exceed expectations" will receive $750 and "outstanding workers" will see an extra $1,000 in their August paychecks[142]

Energy

Indiana's power production chiefly consists of the consumption of fossil fuels, mainly coal. Indiana has 24 coal power plants, including the largest coal power plant in the United States, Gibson Generating Station, located across the Wabash River from Mount Carmel, Illinois. Indiana is also home to the coal-fired plant with the highest sulfur dioxide emissions in the United States, the Gallagher power plant just west of New Albany.[143]

The state has an estimated coal reserves of 57 billion tons; state mining operations produces 35 million tons of coal annually.[144] Indiana also possesses at least 900 million barrels of petroleum reserves in the Trenton Field, though not easily recoverable. While Indiana has made commitments to increasing use of renewable resources such as wind, hydroelectric, biomass, or solar power, however, progress has been very slow, mainly because of the continued abundance of coal in Southern Indiana. Most of the new plants in the state have been coal gasification plants. Another source is hydroelectric power.

Wind power is now being developed. New estimates in 2006 raised the wind capacity for Indiana from 30 MW at 50 m turbine height to 40,000 MW at 70 m, and to 130,000 MW at 100 m, in 2010, the height of newer turbines.[145] As of the end of 2011, Indiana has installed 1,340 MW of wind turbines.[146]

- Sources of energy (2009)

See table below for individual facilities.

| Fuel | Capacity | Percent of total consumed | Percent of total production | Number of plants/units |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coal | 22,190.5 MW | 63% | 88.5% | 28 plants |

| Natural gas | 2,100 MW | 29% | 10.5% | 15 facilities *Often used in peaking stations |

| Wind (Currently the fastest-growing form of energy in Indiana) |

530.5 MW 1,836.5 MW when all current wind farms are complete |

? | ? | 4 farms appx 1,000–1,100 towers total |

| Coal gasification | 600 MW | ? | ? | 1 facility under construction |

| Petroleum | 575 MW | 7.5% | 1.5% | 10 units |

| Hydroelectric | 64 MW | 0.0450% | 0.0100% | 1 plant |

| Biomass | 28 MW | 0.0150% | 0.0020% | 1 facility |

| Wood and Waste | 18 MW | 0.0013% | 0.0015% | 3 units |

| Geothermal and/or Solar | 0 MW | 0.0% | 0.0 | No facilities at this time |

| Nuclear | 0 MW | 0.0% | 0.0 | No facilities at this time |

| Total | 22,797.5 MW * only includes top number of wind |

100% | 100% | 46 generating facilities |

Transportation

Airports

Indianapolis International Airport serves the greater Indianapolis area and has finished constructing a new passenger terminal. The new airport opened in November 2008 and offers a new midfield passenger terminal, concourses, air traffic control tower, parking garage, and airfield and apron improvements.[147]

Other major airports include Evansville Regional Airport, Fort Wayne International Airport (which houses the 122d Fighter Wing of the Air National Guard), and South Bend International Airport. A long-standing proposal to turn Gary Chicago International Airport into Chicago's third major airport received a boost in early 2006 with the approval of $48 million in federal funding over the next ten years.[148]

The Terre Haute International Airport has no airlines operating out of the facility but is used for private flying. Since 1954, the 181st Fighter Wing of the Indiana Air National Guard has been stationed at the airport. However, the Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) Proposal of 2005 stated that the 181st would lose its fighter mission and F-16 aircraft, leaving the Terre Haute facility as a general-aviation only facility.

The southern part of the state is also served by the Louisville International Airport across the Ohio River in Louisville, Kentucky. The southeastern part of the state is served by the Cincinnati/Northern Kentucky International Airport also across the Ohio River in Hebron, Kentucky. Most residents of Northwest Indiana, which is primarily in the Chicago Metropolitan Area, use the two Chicago airports, O'Hare International Airport and Chicago Midway International Airport.

Highways

The major U.S. Interstate highways in Indiana are Interstate 64 (I-64), I-65, I-265, I-465, I-865, I-69, I-469, I-70, I-74, I-80, I-90, I-94, and I-275. The various highways intersecting in and around Indianapolis, along with its historical status as a major railroad hub, and the canals that once crossed Indiana, are the source of the state's motto, the Crossroads of America. There are also many U.S. routes and state highways maintained by the Indiana Department of Transportation. These are numbered according to the same convention as U.S. Highways. Indiana allows highways of different classifications to have the same number. For example, I-64 and Indiana State Road 64 both exist (rather close to each other) in Indiana, but are two distinct roads with no relation to one another.

County roads

Most Indiana counties use a grid-based system to identify county roads; this system replaced the older arbitrary system of road numbers and names, and (among other things) makes it much easier to identify the sources of calls placed to the 9-1-1 system. Such systems are easier to implement in the glacially flattened northern and central portions of the state. Rural counties in the southern third of the state are less likely to have grids and more likely to rely on unsystematic road names (e.g., Crawford, Harrison, Perry, Scott, and Washington Counties).

There are also counties in the northern portions of the state that have never implemented a grid, or have only partially implemented one. Some counties are also laid out in an almost diamond-like grid system (e.g., Clark, Floyd, Gibson, and Knox Counties). Such a system is also almost useless in those situations as well. Knox County once operated two different grid systems for county roads because the county was laid out using two different survey grids, but has since decided to use road names and combine roads instead.

Notably, the county road grid system of St. Joseph County, whose major city is South Bend, uses perennial (tree) names (i.e. Ash, Hickory, Ironwood, etc.) in alphabetical order for North-South roads and Presidential and other noteworthy names (i.e., Adams, Edison, Lincoln Way, etc.) in alphabetical order for East-West roads. There are exceptions to this rule in downtown South Bend and Mishawaka. Hamilton county just continues the numbered street system from Downtown Indianapolis from 96th Street at the Marion County line to 296th street at the Tipton County line.

Rail

Indiana has more than 4,255 railroad route miles, of which 91 percent are operated by Class I railroads, principally CSX Transportation and the Norfolk Southern Railway. Other Class I railroads in Indiana include the Canadian National Railway and Soo Line Railroad, a Canadian Pacific Railway subsidiary, as well as Amtrak. The remaining miles are operated by 37 regional, local, and switching and terminal railroads. The South Shore Line is one of the country's most notable commuter rail systems, extending from Chicago to South Bend. Indiana is currently implementing an extensive rail plan that was prepared in 2002 by the Parsons Corporation.[149] Many recreational trails, such as the Monon Trail and Cardinal Greenway, have been created from abandoned rails routes.

Ports

Indiana annually ships over 70 million tons of cargo by water each year, which ranks 14th among all U.S. states. More than half of Indiana's border is water, which includes 400 miles (640 km) of direct access to two major freight transportation arteries: the Great Lakes/St. Lawrence Seaway (via Lake Michigan) and the Inland Waterway System (via the Ohio River). The Ports of Indiana manages three major ports which include Burns Harbor, Jeffersonville, and Mount Vernon.[150]

In Evansville, three public and several private port facilities receive year-round service from five major barge lines operating on the Ohio River. Evansville has been a U.S. Customs Port of Entry for more than 125 years. Because of this, it is possible to have international cargo shipped to Evansville in bond. The international cargo can then clear Customs in Evansville rather than a coastal port.

Education

Indiana's 1816 constitution was the first in the country to implement a state-funded public school system. It also allotted one township for a public university.[151] However, the plan turned out to be far too idealistic for a pioneer society, as tax money was not accessible for its organization. In the 1840s, Caleb Mills pressed the need for tax-supported schools, and in 1851 his advice was included in the new state constitution.

Although the growth of the public school system was held up by legal entanglements, many public elementary schools were in use by 1870. Most children in Indiana attend public schools, but nearly 10% attend private schools and parochial schools. About one-half of all college students in Indiana are enrolled in state-supported four-year schools.

The largest educational institution is Indiana University, the flagship campus of which was endorsed as Indiana Seminary in 1820. Indiana State University was established as the state's Normal School in 1865; Purdue University was chartered as a land-grant college in 1869. The three other independent state universities are Vincennes University (Founded in 1801 by the Indiana Territory), Ball State University (1918) and University of Southern Indiana (1965 as ISU - Evansville).

Many of the private colleges and universities in Indiana are affiliated with religious groups. The University of Notre Dame and the University of Saint Francis are popular Roman Catholic schools. Universities affiliated with Protestant denominations include Anderson University, Butler University, Indiana Wesleyan University, Taylor University, Franklin College, Hanover College, DePauw University, Earlham College, Valparaiso University, University of Indianapolis,[111] and University of Evansville.[152]

The state's community college system, Ivy Tech Community College of Indiana, serves nearly 200,000 students annually, making it the state's largest public post-secondary educational institution and the nation's largest singly accredited statewide community college system.[153] In 2008, the Indiana University system agreed to shift most of its associate (2-year) degrees to the Ivy Tech Community College System.[154]

The state has several universities ranked among the best in 2013 rankings of the U.S. News & World Report. The University of Notre Dame is ranked among the top 20, with Indiana University Bloomington and Purdue University ranking in the top 100. Indiana University - Purdue University Indianapolis (IUPUI) has recently made it into the top 200 U.S. News & World Report rankings. Butler, Valparaiso, and the University of Evansville are ranked among the top ten in the Regional University Midwest Rankings. Purdue's engineering programs are ranked eighth in the country. In addition, Taylor University is ranked first in the Regional College Midwest Rankings and Rose-Hulman Institute of Technology has been considered the top Undergraduate Engineering school (where a doctorate is not offered) for 15 consecutive years.[155][156][157][158]

Sports

Professional teams

As of 2013 Indiana has produced more National Basketball Association (NBA) players per capita than any other state. Muncie has produced the most per capita of any American city, with two other Indiana cities in the top ten.[159] It has a rich basketball heritage that reaches back to the formative years of the sport itself. The Indiana Pacers of the NBA play their home games at Bankers Life Fieldhouse; they began play in 1967 in the American Basketball Association (ABA) and joined the NBA when the leagues merged in 1976. Although James Naismith developed basketball in Springfield, Massachusetts in 1891, Indiana is where high school basketball was born. In 1925, Naismith visited an Indiana basketball state finals game along with 15,000 screaming fans and later wrote "Basketball really had its origin in Indiana, which remains the center of the sport." The 1986 film Hoosiers is inspired by the story of the 1954 Indiana state champions Milan High School. Professional basketball player Larry Bird was born in West Baden Springs and was raised in French Lick. He went on to lead the Boston Celtics to the NBA championship in 1981, 1984, and 1986.[160]

Indianapolis is home to the Indianapolis Colts. The Colts are members of the South Division of the American Football Conference. The Colts have roots back to 1913 as the Dayton Triangles. They became an official team after moving to Baltimore, MD, in 1953. In 1984, the Colts relocated to Indianapolis, leading to an eventual rivalry with the Baltimore Ravens. After calling the RCA Dome home for 25 years, the Colts currently play their home games at Lucas Oil Stadium in Indianapolis. While in Baltimore, the Colts won the 1970 Super Bowl. In Indianapolis, the Colts won Super Bowl XLI, bringing the franchise total to two. In recent years the Colts have regularly competed in the NFL playoffs.

Auto racing

Indiana has an extensive history with auto racing. Indianapolis hosts the Indianapolis 500 mile race over Memorial Day weekend at the Indianapolis Motor Speedway every May. The name of the race is usually shortened to "Indy 500" and also goes by the nickname "The Greatest Spectacle in Racing." The race attracts over 250,000 people every year making it the largest single day sporting event in the world. The track also hosts the Allstate 400 at the Brickyard (NASCAR) and the Red Bull Indianapolis Grand Prix (MotoGP). From 2000 to 2007, it hosted the United States Grand Prix (Formula One). Indiana features the world's largest and most prestigious drag race, the NHRA Mac Tools U.S. Nationals, held each Labor Day weekend at Lucas Oil Raceway at Indianapolis in Clermont, Indiana. Indiana is also host to two major unlimited hydroplane racing power boat race circuits in the major H1 Unlimited league: Thunder on the Ohio (Evansville, Indiana) and the Madison Regatta (Madison, Indiana).

Teams and venues

The following table shows the professional sports teams in Indiana. Teams in bold are in major professional leagues.

| Club | Sport | League | Venue (capacity) | Attendance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Indianapolis Colts | American football | National Football League | Lucas Oil Stadium (62,400) | 65,375 |

| Indiana Pacers | Basketball | National Basketball Association | Bankers Life Fieldhouse (18,165) | 16,706 |

| Indy Eleven | Soccer | North American Soccer League | Michael Carroll Stadium (12,000) | 10,465 |

| Indianapolis Indians | Baseball | International League (AAA) | Victory Field (14,230) | 9,433 |

| Indiana Fever | Basketball | Women's National Basketball Association | Bankers Life Fieldhouse (18,165) | 7,900 |

| Indy Fuel | Ice Hockey | ECHL | Fairgrounds Coliseum (6,300) | 3,837 |

| Fort Wayne Komets | Ice Hockey | ECHL | Allen County War Memorial Coliseum (8,352) | 7,277 |

| Fort Wayne Mad Ants | Basketball | NBA Development League | War Memorial Coliseum (13,000) | 2,910 |

| Evansville Thunderbolts | Ice Hockey | Southern Professional Hockey League | Ford Center (9,000) | |

The following is a table of sports venues in Indiana that have a capacity in excess of 30,000:

| Facility | Capacity | City | Tenants |

|---|---|---|---|

| Indianapolis Motor Speedway | 257,325 | Speedway | Indianapolis 500 |

| Notre Dame Stadium | 80,795 | South Bend | Notre Dame Fighting Irish |

| Lucas Oil Stadium | 63,000 | Indianapolis | Indianapolis Colts |

| Ross-Ade Stadium | 62,500 | West Lafayette | Purdue Boilermakers |

| Memorial Stadium | 52,929 | Bloomington | Indiana Hoosiers |

College sports

Indiana has had great sports success at the collegiate level.

In men's basketball, the Indiana Hoosiers have won five NCAA national championships and 21 Big Ten Conference championships. The Purdue Boilermakers were selected as the national champions in 1932 before the creation of the tournament, and have won 22 Big Ten championships. The Boilermakers along with the Notre Dame Fighting Irish have both won a national championship in women's basketball.

In college football, the Notre Dame Fighting Irish have won 11 consensus national championships, as well as the Rose Bowl Game, Cotton Bowl Classic, Orange Bowl and Sugar Bowl. Meanwhile, the Purdue Boilermakers have won 10 Big Ten championships and have won the Rose Bowl and Peach Bowl.

Schools fielding NCAA Division I athletic programs include:

See also

- Index of Indiana-related articles

- Outline of Indiana – organized list of topics about Indiana

References

- 1 2 3 "Table 1. Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for the United States, Regions, States, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015" (CSV). U.S. Census Bureau. December 24, 2015. Retrieved December 24, 2015.

- 1 2 "Elevations and Distances in the United States". United States Geological Survey. 2001. Retrieved October 21, 2011.

- 1 2 Elevation adjusted to North American Vertical Datum of 1988.

- ↑ William Vincent D'Antonio; Robert L. Beck. "Indiana – Settlement patterns and demographic trends". eb.com. Retrieved January 3, 2012.

- ↑ "Gross Domestic Product by State". U. S. Bureau of Economic Analysis. Retrieved April 17, 2014.

- ↑ An earlier use of the name dates to the 1760s, when it referenced a tract of land under control of the Commonwealth of Virginia, but the area's name was discarded when it became a part of that state. See Hodgin, Cyrus (1903). "The Naming of Indiana" (pdf transcription). Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana, Historical Society. Wayne County, Indiana, Historical Society. 1 (1): 3–11. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ↑ A portion of the Northwest Territory's eastern section became the state of Ohio in 1803. The Michigan Territory was established in 1805 from part of the Indiana Territory's northern lands and four years later, in 1809, the Illinois counties were separated from the Indiana Territory to create the Illinois Territory. See John D. Barnhart; Dorothy L. Riker (1971). Indiana to 1816: The Colonial Period. The History of Indiana. I. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Bureau and the Indiana Historical Society. pp. 311–13,337, 353, 355, and 432.

- ↑ Stewart, George R. (1967) [1945]. Names on the Land: A Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States (Sentry edition (3rd) ed.). Houghton Mifflin. p. 191.

- ↑ Hodgin, Cyrus (1903). "The Naming of Indiana" (pdf transcriptionaccessdate=2014-1-16). Papers of the Wayne County, Indiana, Historical Society. Wayne County, Indiana, Historical Society. 1 (1): 3–11.

- ↑ Haller, Steve (Fall 2008). "The Meanings of Hoosier: 175 Years and Counting" (PDF). Traces of Indiana and Midwestern History. Indianapolis: Indiana Historical Society. 20 (4): 5 and 6. ISSN 1040-788X. Retrieved January 23, 2014.

- ↑ Graf, Jeffery. "The Word Hoosier". Indiana University – Bloomington. Retrieved February 27, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 "Prehistoric Indians of Indiana" (PDF). State of Indiana. Retrieved July 5, 2009.

- ↑ Allison, p. 17.

- ↑ Brill, p. 31–32.

- 1 2 "Northwest Ordinance of 1787". State of Indiana. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ Brill, p. 33.

- 1 2 3 4 "Government at Crossroads: An Indiana chronology". The Herald Bulletin. January 5, 2008. Retrieved July 22, 2009.

- ↑ Brill, p. 35.

- ↑ Brill, pp. 36–37.

- 1 2 "The History of Indiana". History. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- ↑ Data on selected ancestry groups.

- ↑ Vanderstel, David G. "The 1851 Indiana Constitution by David G. Vanderstel". State of Indiana. Retrieved July 24, 2009.

- ↑ Funk, pp. 23–24, 163.

- ↑ Gray 1995, p. 156.

- ↑ Funk, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Foote, Shelby (1974). The Civil War; a Narrative, Red River to Appomattox. Random House. pp. 343–344.

- ↑ Gray 1995, p. 202.

- ↑ Gray 1995, p. 13.

- ↑ Brill, p. 47.

- ↑ Branson, Ronald. "Paul V. McNutt". County History Preservation Society. Archived from the original on December 4, 2008. Retrieved July 26, 2009.

- 1 2 Pell, p. 31.

- ↑ Gray 1995, p. 350.

- ↑ Peck, Merton J. & Scherer, Frederic M. The Weapons Acquisition Process: An Economic Analysis (1962) Harvard Business School p.111

- ↑ Haynes, Kingsley E.; Machunda, Zachary B (1987). Economic Geography. pp. 319–333.

- ↑ Gray 1995, p. 382.

- ↑ "Indiana - Race and Hispanic Origin: 1800 to 1990". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved December 28, 2012.

- ↑ Gray 1995, pp. 391–392.

- ↑ Indiana Historical Bureau. "History and Origins". Indiana Historical Bureau. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- ↑ Singleton, Christopher J. "Auto industry jobs in the 1980s: a decade of transition" (PDF). United States Bureau of Labor Statistics. Retrieved July 28, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Profile of the People and Land of the United States". National Atlas of the United States. Retrieved August 17, 2012.

- ↑ Moore, p. 11.

- 1 2 3 "The Geography of Indiana". Netstate. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ "NOAA's Great Lakes Region". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. April 25, 2007. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Indiana". Funk & Wagnalls New World Encyclopedia. Funk & Wagnalls.

- ↑ Meredith, Robyn (March 7, 1997). "Big-Shouldered River Swamps Indiana Town". The New York Times. Retrieved August 19, 2009.

- ↑ Logan, Cumings, Malott, Visher, Tucker & Reeves, p. 82

- ↑ Pell, p. 56.

- ↑ Moore, p. 13.

- ↑ Logan, Cumings, Malott, Visher, Tucker & Reeves, p. 70

- ↑ Logan, William N.; Edgar Roscoe Cumings; Clyde Arnett Malott; Stephen Sargent Visher; et al. (1922). Handbook of Indiana Geology. Indiana Department of Conservation/. p. 257.

- ↑ "Information Bulletin #4 (Second Amendment), Outstanding Rivers List for Indiana" (PDF). Natural Resources Commission. May 30, 2007. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ Boyce, Brian M (August 29, 2009). "Terre Haute's Top 40: From a trickle in Ohio to the Valley's signature waterway, the Wabash River is forever a part of Terre Haute". Tribune-Star. Retrieved September 24, 2009.

- ↑ Jerse, Dorothy (March 4, 2006). "Looking Back: Gov. Bayh signs bill making Wabash the official state river in 1996". Tribune-Star. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- ↑ Ozick, Cynthia (November 9, 1986). "Miracle on Grub street; Stockholm". The New York Times.

- ↑ Fantel, Hans (October 14, 1984). "Sound; CDs make their mark on the Wabash Valley". The New York Times.

- ↑ "INDIANA LAKES LISTING" (PDF). Retrieved January 26, 2015.

- ↑ Leider, Polly (January 26, 2006). "A Town With Backbone: Warsaw, Ind.". CBS News. Retrieved September 29, 2009.

- ↑ Bridges, David (November 28, 2007). "Life in Indiana — Telegraph Mentor". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- 1 2 "NWS Climate Data". NWS. Retrieved December 23, 2010.

- ↑ "Indiana — Climate". City-Data.com. Retrieved July 4, 2009.

- ↑ Engineering Analysis Inc. (April 12, 2012). "Mississippi Remains #1 Among Top Twenty Tornado-Prone States". mindspring.com. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ Engineering Analysis Inc. (October 28, 2011). "Six States Contain Twelve of the Top Twenty Tornado-Prone Cities (revised version)". mindspring.com. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ Kellogg, Becky (March 8, 2011). "Tornado Expert Ranks Top Tornado Cities". The Weather Channel. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ In an earlier 2008 report, Indiana was listed as one of the most tornado-prone states in the United States, ranking sixth, while South Bend was ranked the 14th most tornado-prone city in the country, ahead of cities such as Houston, Texas, and Wichita, Kansas. See Mecklenburg, Rick (May 1, 2008). "Is Indiana the new Tornado Alley?". SouthBendTribune.com. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ In a published list of the most tornado-prone states and cities in April 2008, Indiana came in first and South Bend ranked 16th. See Henderson, Mark (May 2, 2008). "Top 20 Tornado Prone Cities and States Announced". WIFR. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ↑ Henderson, Mark (May 2, 2008). "Top 20 Tornado Prone Cities and States Announced". WIFR. Retrieved August 17, 2009.

- ↑ "Climate Facts". Indiana State Climate Office. Retrieved May 29, 2009.

- ↑ "Indiana climate averages". Weatherbase. Retrieved November 12, 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Guide to 2010 Census State and Local Geography - Indiana". U.S. Census Bureau. April 21, 2014. Retrieved August 13, 2012.

- ↑ A 2008 news report indicated there were 13 metropolitan areas in Indiana. See Dresang, Joel (July 30, 2008). "Automaking down, unemployment up". Milwaukee Journal Sentinel. Retrieved August 14, 2009.

- ↑ Indiana's territorial capitals were Vincennes and later Corydon, which also became Indiana's first state capital when it became a state.

- ↑ "Indiana". Indiana Business Research Center, Indiana University, Kelley School of Business. Retrieved August 14, 2012.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". census.gov. Retrieved March 5, 2016.

- ↑ Resident Population Data. "Resident Population Data – 2010 Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved December 23, 2012.

- ↑ "2010 Census Centers of Population by state". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved August 15, 2012.

- ↑ Over the previous decade, Indiana's population center has shifted slightly to the northwest. In the 2000 U.S. Census, Indiana's center of population was located in Hamilton County, in the town of Sheridan. See "Population and Population Centers by State". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on June 22, 2013. Retrieved November 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Metro and Nonmetro Counties in Indiana" (PDF). Rural Policy Research Institute. Retrieved October 10, 2009.