Indigenous peoples

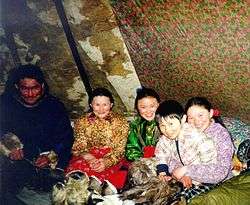

Indigenous peoples, also known as first peoples, aboriginal peoples, native peoples, or autochthonous peoples, are ethnic groups who are descended from and identify with the original inhabitants of a given region, in contrast to groups that have settled, occupied or colonized the area more recently. Groups are usually described as indigenous when they maintain traditions or other aspects of an early culture that is associated with a given region. Not all indigenous peoples share these characteristics. Indigenous peoples may be either settled in a given locale/region or exhibit a nomadic lifestyle across a large territory, but are generally historically associated with a specific territory on which they depend. Indigenous societies are found in every inhabited climate zone and continent of the world.[1][2]

Since indigenous peoples are often faced with threats to their sovereignty, economic well-being, and their access to resources on which their cultures depend, a special set of political rights in accordance with international law have been set forth by international organizations such as the United Nations, the International Labour Organization and the World Bank.[1] The United Nations has issued a Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples to guide member-state national policies to collective rights of indigenous people—such as culture, identity, language, and access to employment, health, education, and natural resources. Estimates put the total population of indigenous peoples from 220 million to 350 million.[3]

Etymology

The adjective indigenous is derived from the Latin word indigena, which is based on the root gen- 'to be born' with an archaic form of the prefix in 'in'.[4] Any given people, ethnic group or community may be described as indigenous in reference to some particular region or location that they see as their traditional tribal land claim.[5] Other terms used to refer to indigenous populations are aboriginal, native, original, or first (as in Canada's First Nations).

The use of the term peoples in association with the indigenous is derived from the 19th century anthropological and ethnographic disciplines that Merriam-Webster Dictionary defines as "a body of persons that are united by a common culture, tradition, or sense of kinship, which typically have common language, institutions, and beliefs, and often constitute a politically organized group".[6]

During the late twentieth century, the term Indigenous people began to be used to describe a legal category in indigenous law created in international and national legislation; it refers to culturally distinct groups affected by colonization.[7]

James Anaya, former Special Rapporteur on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples, has defined indigenous peoples as "living descendants of pre-invasion inhabitants of lands now dominated by others. They are culturally distinct groups that find themselves engulfed by other settler societies born of forces of empire and conquest".[8][9]

They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal system. The International Day of the World's Indigenous People falls on 9 August as this was the date of the first meeting in 1982 of the United Nations Working Group of Indigenous Populations of the Subcommission on Prevention of Discrimination and Protection of Minorities of the Commission on Human Rights.

National definitions

Throughout history, different states designate the groups within their boundaries that are recognized as indigenous peoples according to international or national legislation by different terms. Indigenous people also include people indigenous based on their descent from populations that inhabited the country when non-indigenous religions and cultures arrived—or at the establishment of present state boundaries—who retain some or all of their own social, economic, cultural and political institutions, but who may have been displaced from their traditional domains or who may have resettled outside their ancestral domains.

The status of the indigenous groups in the subjugated relationship can be characterized in most instances as an effectively marginalized, isolated or minimally participative one, in comparison to majority groups or the nation-state as a whole. Their ability to influence and participate in the external policies that may exercise jurisdiction over their traditional lands and practices is very frequently limited. This situation can persist even in the case where the indigenous population outnumbers that of the other inhabitants of the region or state; the defining notion here is one of separation from decision and regulatory processes that have some, at least titular, influence over aspects of their community and land rights.

In a ground-breaking 1997 decision involving the Ainu people of Japan, the Japanese courts recognised their claim in law, stating that "If one minority group lived in an area prior to being ruled over by a majority group and preserved its distinct ethnic culture even after being ruled over by the majority group, while another came to live in an area ruled over by a majority after consenting to the majority rule, it must be recognised that it is only natural that the distinct ethnic culture of the former group requires greater consideration."[10]

The presence of external laws, claims and cultural mores either potentially or actually act to variously constrain the practices and observances of an indigenous society. These constraints can be observed even when the indigenous society is regulated largely by its own tradition and custom. They may be purposefully imposed, or arise as unintended consequence of trans-cultural interaction. They may have a measurable effect, even where countered by other external influences and actions deemed beneficial or that promote indigenous rights and interests.

United Nations

In 1972 the United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations (WGIP) accepted as a preliminary definition a formulation put forward by Mr. José R. Martínez-Cobo, Special Rapporteur on Discrimination against Indigenous Populations. This definition has some limitations, because the definition applies mainly to pre-colonial populations, and would likely exclude other isolated or marginal societies.[11]

Indigenous communities, peoples, and nations are those that, having a historical continuity with pre-invasion and pre-colonial societies that developed on their territories, consider themselves distinct from other sectors of the societies now prevailing in those territories, or parts of them. They form at present non-dominant sectors of society and are determined to preserve, develop, and transmit to future generations their ancestral territories, and their ethnic identity, as the basis of their continued existence as peoples, in accordance with their own cultural patterns, social institutions and legal systems.

The primary impetus in considering indigenous identity comes from the post-colonial movements and considering the historical impacts on populations by the European imperialism. The first paragraph of the Introduction of a report published in 2009 by the Secretariat of the Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues published a report,[12] states

For centuries, since the time of their colonization, conquest or occupation, indigenous peoples have documented histories of resistance, interface or cooperation with states, thus demonstrating their conviction and determination to survive with their distinct sovereign identities. Indeed, indigenous peoples were often recognized as sovereign peoples by states, as witnessed by the hundreds of treaties concluded between indigenous peoples and the governments of the United States, Canada, New Zealand and others.[13]

In May 2016, the Fifteenth Session of the United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues (UNPFII) affirmed that indigenous people' (also termed aboriginal people, native people, or autochthonous people) are distinctive groups protected in international or national legislation as having a set of specific rights based on their linguistic and historical ties to a particular territory, prior to later settlement, development, and or occupation of a region.[14] The session affirms that since indigenous peoples are vulnerable to exploitation, marginalization, oppression, forced assimilation, and genocide by nation states formed from colonizing populations or by politically dominant, different ethnic groups, special protection of individuals and communities maintaining ways of life indigenous to their regions, are entitled to special protection.

History

Classical antiquity

Greek sources of the Classical period acknowledge the prior existence of indigenous people(s), whom they referred to as "Pelasgians". These peoples inhabited lands surrounding the Aegean Sea before the subsequent migrations of the Hellenic ancestors claimed by these authors. The disposition and precise identity of this former group is elusive, and sources such as Homer, Hesiod and Herodotus give varying, partially mythological accounts. However, it is clear that cultures existed whose indigenous characteristics were distinguished by the subsequent Hellenic cultures (and distinct from non-Greek speaking "foreigners", termed "barbarians" by the historical Greeks).

Greco-Roman society flourished between 250 BC and 480 AD and commanded successive waves of conquests that gripped more than half of the globe. But because already existent populations within other parts of Europe at the time of classical antiquity had more in common culturally speaking with the Greco-Roman world, the intricacies involved in expansion across the European frontier were not so contentious relative to indigenous issues.[15]

But when it came to expansion in other parts of the world, namely Asia, Africa, and the Middle East, then totally new cultural dynamics had entered into the equation, so to speak, and one sees here of what was to take the Americas, South East Asia, and the Pacific by storm a few hundred years later. The idea that peoples who possessed cultural customs and racial appearances strikingly different from those of the colonizing power is no new idea borne out of the Medieval period or the Enlightenment.

European expansion and colonialism

The rapid and extensive spread of the various European powers from the early 15th century onwards had a profound impact upon many of the indigenous cultures with whom they came into contact. The exploratory and colonial ventures in the Americas, Africa, Asia and the Pacific often resulted in territorial and cultural conflict, and the intentional or unintentional displacement and devastation of the indigenous populations.

The Canary Islands had an indigenous population called the Guanches whose origin is still the subject of discussion among historians and linguists.[16]

Population and distribution

Indigenous societies range from those who have been significantly exposed to the colonizing or expansionary activities of other societies (such as the Maya peoples of Mexico and Central America) through to those who as yet remain in comparative isolation from any external influence (such as the Sentinelese and Jarawa of the Andaman Islands).

Precise estimates for the total population of the world's Indigenous peoples are very difficult to compile, given the difficulties in identification and the variances and inadequacies of available census data. The United Nations estimates that there are over 370 million indigenous people living in over 70 countries worldwide.[17] This would equate to just fewer than 6% of the total world population. This includes at least 5000 distinct peoples[18] in over 72 countries.

Contemporary distinct indigenous groups survive in populations ranging from only a few dozen to hundreds of thousands and more. Many indigenous populations have undergone a dramatic decline and even extinction, and remain threatened in many parts of the world. Some have also been assimilated by other populations or have undergone many other changes. In other cases, indigenous populations are undergoing a recovery or expansion in numbers.

Certain indigenous societies survive even though they may no longer inhabit their "traditional" lands, owing to migration, relocation, forced resettlement or having been supplanted by other cultural groups. In many other respects, the transformation of culture of indigenous groups is ongoing, and includes permanent loss of language, loss of lands, encroachment on traditional territories, and disruption in traditional lifeways due to contamination and pollution of waters and lands.

Indigenous peoples by region

Indigenous populations are distributed in regions throughout the globe. The numbers, condition and experience of indigenous groups may vary widely within a given region. A comprehensive survey is further complicated by sometimes contentious membership and identification.

Africa

In the post-colonial period, the concept of specific indigenous peoples within the African continent has gained wider acceptance, although not without controversy. The highly diverse and numerous ethnic groups that comprise most modern, independent African states contain within them various peoples whose situation, cultures and pastoralist or hunter-gatherer lifestyles are generally marginalized and set apart from the dominant political and economic structures of the nation. Since the late 20th century these peoples have increasingly sought recognition of their rights as distinct indigenous peoples, in both national and international contexts.

Though the vast majority of African peoples are indigenous in the sense that they originate from that continent and middle and south east Asia—in practice, identity as an indigenous people per the modern definition is more restrictive, and certainly not every African ethnic group claims identification under these terms. Groups and communities who do claim this recognition are those who, by a variety of historical and environmental circumstances, have been placed outside of the dominant state systems, and whose traditional practices and land claims often come into conflict with the objectives and policies implemented by governments, companies and surrounding dominant societies.

Given the extensive and complicated history of human migration within Africa, being the "first peoples in a land" is not a necessary precondition for acceptance as an indigenous people. Rather, indigenous identity relates more to a set of characteristics and practices than priority of arrival. For example, several populations of nomadic peoples such as the Tuareg of the Sahara and Sahel regions now inhabit areas where they arrived comparatively recently; their claim to indigenous status (endorsed by the African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights) is based on their marginalization as nomadic peoples in states and territories dominated by sedentary agricultural peoples.

Americas

Indigenous peoples of the American continent are broadly recognized as being those groups and their descendants who inhabited the region before the arrival of European colonizers and settlers (i.e., Pre-Columbian). Indigenous peoples who maintain, or seek to maintain, traditional ways of life are found from the high Arctic north to the southern extremities of Tierra del Fuego.

The impact of European colonization of the Americas on the indigenous communities has been in general quite severe, with many authorities estimating ranges of significant population decline primarily due to disease but also violence. The extent of this impact is the subject of much continuing debate. Several peoples shortly thereafter became extinct, or very nearly so.

All nations in North and South America have populations of indigenous peoples within their borders. In some countries (particularly Latin American), indigenous peoples form a sizable component of the overall national population—in Bolivia they account for an estimated 56%–70% of the total nation, and at least half of the population in Guatemala and the Andean and Amazonian nations of Peru. In English, indigenous peoples are collectively referred to by different names that vary by region and include such ethnonyms as Native Americans, Amerindians, and American Indians. In Spanish or Portuguese speaking countries one finds the use of terms such as pueblos indígenas, amerindios, povos nativos, povos indígenas, and in Peru, Comunidades Nativas (Native Communities), particularly among Amazonian societies like the Urarina[19] and Matsés. In Chile there are indigenous tribes like the Mapuches in the Center-South and the Aymaras in the North, also the Rapa Nui indigenous to Easter Island are a Polynesian tribe.

In Brazil, the term índio (Portuguese pronunciation: [ˈĩdʒi.u] or ˈĩdʒju) is used by most of the population, the media, the indigenous peoples themselves and even the government (FUNAI is acronym for the Fundação Nacional do Índio) (National Indio Foundation), although its Hispanic equivalent indio is widely not considered politically correct and falling into disuse.

%2C_1933_-_1942_-_NARA_-_519947.jpg)

Aboriginal peoples in Canada comprise the First Nations,[20] Inuit[21] and Métis.[22] The descriptors "Indian" and "Eskimo" are falling into disuse in Canada.[23][24] There are currently over 600 recognized First Nations governments or bands encompassing 1,272,790 2006 peoples spread across Canada with distinctive Aboriginal cultures, languages, art, and music.[25][26][27] National Aboriginal Day recognises the cultures and contributions of Aboriginals to the history of Canada

The Inuit have achieved a degree of administrative autonomy with the creation in 1999 of the territories of Nunavik (in Northern Québec), Nunatsiavut (in Northern Labrador) and Nunavut, which was until 1999 a part of the Northwest Territories. The self-ruling Danish territory of Greenland is also home to a majority population of indigenous Inuit (about 85%).

In the United States, the combined populations of Native Americans, Inuit and other indigenous designations totalled 2,786,652 (constituting about 1.5% of 2003 US census figures). Some 563 scheduled tribes are recognized at the federal level, and a number of others recognized at the state level.

In Mexico, approximately 6,011,202 (constituting about 6.7% of 2005 Mexican census figures) identify as Indígenas (Spanish for natives or indigenous peoples). In the southern states of Chiapas, Yucatán and Oaxaca they constitute 26.1%, 33.5% and 35.3%, respectively, of the population. In these states several conflicts and episodes of civil war have been conducted, in which the situation and participation of indigenous societies were notable factors (see for example EZLN).

The Amerindians make up 0.4% of all Brazilian population, or about 700,000 people.[28] Indigenous peoples are found in the entire territory of Brazil, although the majority of them live in Indian reservations in the North and Center-Western part of the country. On 18 January 2007, FUNAI reported that it had confirmed the presence of 67 different uncontacted tribes in Brazil, up from 40 in 2005. With this addition Brazil has now overtaken the island of New Guinea as the country having the largest number of uncontacted tribes.[29]

Asia

The vast regions of Asia contain the majority of the world's present-day Indigenous populations, about 70% according to IWGIA figures.

Western Asia

The Yazidis are indigenous to the Sinjar mountain range in northern Iraq.

The indigenous people of Northern Iraq are the Assyrians.[30] They claim descent from the ancient Neo-Assyrian Empire and Akkadians, and lived in what was Assyria, their original homeland.

South Asia

The indigenous peoples of the Chittagong Hill Tracts are the Buddhist Chakma people (Jumma people).

The most substantial populations are in India, which constitutionally recognizes a range of "Scheduled Tribes" within its borders. These various peoples (collectively referred to as Adivasis, or tribal peoples) number about 68 million (1991 census figures, approximately 8% of the total national population).

There are also indigenous people residing in the hills of Northern, North-eastern and Southern India like the Ladakhi, Kinnaurs, Lepcha, Bhutia (of Sikkim), Naga (of Nagaland), Karbi (formely known as Mikir & are in Assam, Nagaland, Meghalaya, Arunachal Pradesh, Manipur, and even in Bangladesh), Bodo, Munda people of Chota Nagpur Plateau, Mizo (of Mizoram), Kodava (of Kodagu), Toda, Kurumba, Kota (of the Nilgiris), Irulas and others.

The Jats are indigenous people of ancient India, and can be tracked down to 4th century BC.[31]

North Asia

The Russians invaded Siberia and conquered the indigenous natives in the 17th-18th centuries.

Nivkh people are an ethnic group indigenous to Sakhalin, having a few speakers of the Nivkh language, but their fisher culture has been endangered due to the development of oil field of Sakhalin from 1990s.[32]

Eastern Asia

Ainu people are an ethnic group indigenous to Hokkaidō, the Kuril Islands, and much of Sakhalin. As Japanese settlement expanded, the Ainu were pushed northward and fought against the Japanese in Shakushain's Revolt and Menashi-Kunashir Rebellion, until by the Meiji period they were confined by the government to a small area in Hokkaidō, in a manner similar to the placing of Native Americans on reservations.[33]

The Dzungar Oirats are the natives of Dzungaria in Northern Xinjiang.

The Pamiris are the native people of Tashkurgan in Xinjiang.

The Ryukyuan people are indigenous to the Ryukyu Islands.

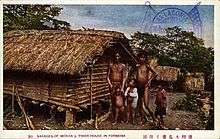

The languages of Taiwanese aborigines have significance in historical linguistics, since in all likelihood Taiwan was the place of origin of the entire Austronesian language family, which spread across Oceania.[34][35][36]

Southeast Asia

The Cham are the indigenous people of the former state of Champa which was conquered by Vietnam in the Cham–Vietnamese wars during Nam tiến. The Cham in Vietnam are only recognized as a minority, and not as an indigenous people by the Vietnamese government despite being indigenous to the region.

The Degar (Montagnards) are the natives of the Central Highlands (Vietnam) and were conquered by the Vietnamese in the Nam tiến.

The Khmer Krom are the native people of the Mekong Delta and Saigon which were acquired by Vietnam from Cambodian King Chey Chettha II in exchange for a Vietnamese princess.

The Javanese, Sundanese, Bantenese, Betawi, Tengger, Osing, Badui, Madurese, Malays, Batak, Minangkabau, Acehnese, Lampung, Kubu, Dayak, Banjar, Makassarese, Buginese, Mandar, Minahasa, Buton, Gorontalo, Toraja, Bajau, Balinese, Sasak, Nuaulu, Manusela, Wemale, Dani, Bauzi, Asmat are indigenous peoples in Indonesia. There are over 300 ethnic groups in Indonesia.[37] 200 million of those are of Native Indonesian ancestry.

The indigenous people of Cordillera Administrative Region in the Philippines are the Igorot people.

The indigenous peoples of Mindanao are the Lumad peoples and the Moro (Tausug, Maguindanao Maranao and others) who also live in the Sulu archipelago.

Europe

In Europe, present-day indigenous populations as recognized by the UN are relatively few, mainly confined to northern and far-eastern reaches of this Eurasian peninsula. Nevertheless, the ethnic groups traditionally inhabiting most, if not all, European countries are considered to be indigenous to Europe. This includes the majority populations.

Notable minority indigenous populations in Europe include the Basque people of northern Spain and southern France, the Sami people of northern Scandinavia, the Nenets and other Samoyedic peoples of the northern Russian Federation, and the Komi peoples of the western Urals, beside the Circassians in the North Caucasus.

Oceania

In Australia the indigenous populations are the Aboriginal Australians, within which are many different nations and tribes, and the Torres Strait Islanders. These groups are often spoken of as Indigenous Australians.

Many of the present-day Pacific Island nations in the Oceania region were originally populated by Polynesian, Melanesian and Micronesian peoples over the course of thousands of years. European colonial expansion in the Pacific brought many of these under non-indigenous administration. During the 20th century several of these former colonies gained independence and nation-states were formed under local control. However, various peoples have put forward claims for Indigenous recognition where their islands are still under external administration; examples include the Chamorros of Guam and the Northern Marianas, and the Marshallese of the Marshall Islands.

The remains of at least 25 miniature humans, who lived between 1,000 and 3,000 years ago, were recently found on the islands of Palau in Micronesia.[38]

In most parts of Oceania, indigenous peoples outnumber the descendants of colonists. Exceptions include New Zealand and Hawaii. According to the 2013 census, New Zealand Māori make up 14.9% of the population of New Zealand, with less than half (46.5%) of all Māori residents identifying solely as Māori. The Māori are indigenous to Polynesia and settled New Zealand relatively recently, the migrations were thought to have occurred in the 13th century CE. In New Zealand pre-contact Māori tribes were not a single people, thus the more recent grouping into tribal (iwi) arrangements has become a more formal arrangement in more recent times. Many Māori tribal leaders signed a treaty with the British, the Treaty of Waitangi, which formed the modern geo-political entity that is New Zealand.

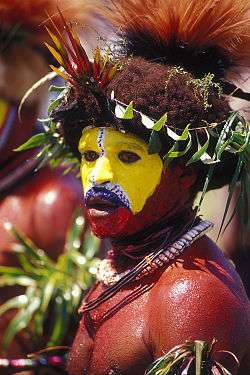

The independent state of Papua New Guinea (PNG) has a majority population of indigenous societies, with more than 700 different tribal groups recognized out of a total population of just over 5 million. The PNG Constitution and other Acts identify traditional or custom-based practices and land tenure, and explicitly set out to promote the viability of these traditional societies within the modern state. However, conflicts and disputes concerning land use and resource rights continue between indigenous groups, the government, and corporate entities.

Indigenous rights and other issues

| Part of a series on |

| Indigenous rights |

|---|

| Rights |

| Governmental organizations |

| NGOs and political groups |

| Issues |

| Legal representation |

| Category |

Indigenous peoples confront a diverse range of concerns associated with their status and interaction with other cultural groups, as well as changes in their inhabited environment. Some challenges are specific to particular groups; however, other challenges are commonly experienced.[39] These issues include cultural and linguistic preservation, land rights, ownership and exploitation of natural resources, political determination and autonomy, environmental degradation and incursion, poverty, health, and discrimination.

The interaction between indigenous and non-indigenous societies throughout history has been complex, ranging from outright conflict and subjugation to some degree of mutual benefit and cultural transfer. A particular aspect of anthropological study involves investigation into the ramifications of what is termed first contact, the study of what occurs when two cultures first encounter one another. The situation can be further confused when there is a complicated or contested history of migration and population of a given region, which can give rise to disputes about primacy and ownership of the land and resources.

Wherever indigenous cultural identity is asserted, common societal issues and concerns arise from the indigenous status. These concerns are often not unique to indigenous groups. Despite the diversity of Indigenous peoples, it may be noted that they share common problems and issues in dealing with the prevailing, or invading, society. They are generally concerned that the cultures of Indigenous peoples are being lost and that indigenous peoples suffer both discrimination and pressure to assimilate into their surrounding societies. This is borne out by the fact that the lands and cultures of nearly all of the peoples listed at the end of this article are under threat. Notable exceptions are the Sakha and Komi peoples (two of the northern indigenous peoples of Russia), who now control their own autonomous republics within the Russian state, and the Canadian Inuit, who form a majority of the territory of Nunavut (created in 1999). In Australia, a landmark case, Mabo v Queensland (No 2),[40] saw the High Court of Australia reject the idea of terra nullius. This rejection ended up recognizing that there was a pre-existing system of law practiced by the Meriam people.

It is also sometimes argued that it is important for the human species as a whole to preserve a wide range of cultural diversity as possible, and that the protection of indigenous cultures is vital to this enterprise.

Human rights violation

The Bangladesh Government has stated that there are "no Indigenous Peoples in Bangladesh".[41] This has angered the Indigenous Peoples of Chittagong Hill Tracts, Bangladesh, collectively known as the Jumma.[42] Experts have protested against this move of the Bangladesh Government and have questioned the Government's definition of the term "Indigenous Peoples".[43][44] This move by the Bangladesh Government is seen by the Indigenous Peoples of Bangladesh as another step by the Government to further erode their already limited rights.[45]

Both Hindu and Chams have experienced religious and ethnic persecution and restrictions on their faith under the current Vietnamese government, with the Vietnamese state confisticating Cham property and forbidding Cham from observing their religious beliefs. Hindu temples were turned into tourist sites against the wishes of the Cham Hindus. In 2010 and 2013 several incidents occurred in Thành Tín and Phươc Nhơn villages where Cham were murdered by Vietnamese. In 2012, Vietnamese police in Chau Giang village stormed into a Cham Mosque, stole the electric generator, and also raped Cham girls.[46] Cham in the Mekong Delta have also been economically marginalised, with ethnic Vietnamese settling on land previously owned by Cham people with state support.[47]

The French, the Communist North Vietnamese, and the anti-Communist South Vietnamese all exploited and persecuted the Montagnards. North Vietnamese Communists forcibly recruited "comfort girls" from the indigenous Montagnard peoples of the Central Highlands and murdered those who didn't comply, inspired by Japan's use of comfort women.[48] The Vietnamese viewed and dealt with the indigenous Montagnards in the CIDG from the Central Highlands as "savages" and this caused a Montagnard uprising against the Vietnamese.[49] The Vietnamese were originally centered around the Red River Delta but engaged in conquest and seized new lands such as Champa, the Mekong Delta (from Cambodia) and the Central Highlands during Nam Tien, while the Vietnamese received strong Chinese influence in their culture and civilization and were Sinicized, and the Cambodians and Laotians were Indianized, the Montagnards in the Central Highlands maintained their own native culture without adopting external culture and were the true indigenous natives of the region, and to hinder encroachment on the Central Highlands by Vietnamese nationalists, the term Pays Montagnard du Sud-Indochinois PMSI emerged for the Central Highlands along with the natives being addressed by the name Montagnard.[50] The tremendous scale of Vietnamese Kinh colonists flooding into the Central Highlands has significantly altered the demographics of the region.[51] The anti-ethnic minority discriminatory policies by the Vietnamese, environmental degradation, deprivation of lands from the natives, and settlement of native lands by a massive amount of Vietnamese settlers led to massive protests and demonstrations by the Central Highland's indigenous native ethnic minorities against the Vietnamese in January–February 2001 and this event gave a tremendous blow to the claim often published by the Vietnamese government that in Vietnam There has been no ethnic confrontation, no religious war, no ethnic conflict. And no elimination of one culture by another.[52]

Health issues

In December 1993, the United Nations General Assembly proclaimed the International Decade of the World's Indigenous People, and requested UN specialized agencies to consider with governments and indigenous people how they can contribute to the success of the Decade of Indigenous People, commencing in December 1994. As a consequence, the World Health Organization, at its Forty-seventh World Health Assembly established a core advisory group of indigenous representatives with special knowledge of the health needs and resources of their communities, thus beginning a long-term commitment to the issue of the health of indigenous peoples.[53]

The WHO notes that "Statistical data on the health status of indigenous peoples is scarce. This is especially notable for indigenous peoples in Africa, Asia and eastern Europe", but snapshots from various countries, where such statistics are available, show that indigenous people are in worse health than the general population, in advanced and developing countries alike: higher incidence of diabetes in some regions of Australia;[54] higher prevalence of poor sanitation and lack of safe water among Twa households in Rwanda;[55] a greater prevalence of childbirths without prenatal care among ethnic minorities in Vietnam;[56] suicide rates among Inuit youth in Canada are eleven times higher than the national average;[57] infant mortality rates are higher for indigenous peoples everywhere.[58]

Indigenous worldviews and the global community

International relations (IR) is inherently one born from the Western European modes of thought, and from a view of its early structures and theoretical foundations, including the work of European scholars Hobbes, Locke, and Rousseau, it fails to incorporate Indigenous understandings, which consequently further perpetuate colonization rather than prevent it. International organizations are founded under theoretical IR approaches, and assume the nature of humans, but contradict with the assumption of the nature of humans being inherently competitive and therefore draw conclusions that the Hobbesian "Social Contract" should not exist in International bodies today.

The contradiction seen when comparing the western European tradition of defining human nature to western European nature itself has impacted the ways at which colonial states, like Canada, interact with Indigenous peoples whom became subject to western European models of thought in respect to the definition of human nature, and therefore pure theoretics regarding IR in respect to colonial-Indigenous relations falls short. The shortcoming is mainly due to the vast assumptions made regarding the nature of humans, which fail to consider Indigenous forms of "international relations". The treaty process during the years of pioneer settlement for example served as legal weapons by the western European world to lay claim through its own laws and understands to the vast territory that Indigenous people have been in relationship with since time immemorial. "As exemplified in jurisprudential, statute, and constitutional law, Canada imagines that indigenous peoples have already been incorporated into the state. That is, the Canadian state assumes that indigenous peoples already come under Canadian political jurisdiction[59]". The problem then, in summary, is that IR’s failed ability to relate in an intimate way with the worldviews and teaching that govern Indigenous people is not really International Relations but rather just another naturalized colonial tactic perhaps even un-beware to its beholder. A failure to incorporate Indigenous understandings in the overarching western-European founded study of IR isn’t the problem of Indigenous peoples not being able to adapt or engage with its colonizer as a recognized Westphalia state but that the failed assumption that the western European foundational models of human nature are correct. IR's foundational theories then serve better in understanding western European states of nature.

A key difference in the models of knowledge from an Indigenous worldview and that of the western European founded model is the ways at which both groups behave as collectives in response to one another; cooperation verse competition respectively. In the nature of cooperation women, children, elders, men, all members of society have a place in building the way forward for generations.[60] In the nature of competition only the strongest or those with the means to security have a place in society and those outside that privilege become wards of the protectorate. Ways of contemporary decolonization seek to establish the legitimacy and un-naturalize the assumptions of the nature of humans and institute rather many forms or understanding ourselves, Indigenous and non- Indigenous.

Non-indigenous viewpoints

Indigenous peoples have been denoted primitives, savages,[61] or uncivilized. These terms were common during the heights of European colonial expansion, but still continue in modern times.[62]

During the 17th century, indigenous peoples were commonly labeled "uncivilized". Some philosophers such as Thomas Hobbes considered indigenous people to be merely 'savages', while others are purported to have considered them to be "noble savages". Those who were close to the Hobbesian view tended to believe themselves to have a duty to "civilize" and "modernize" the indigenous. Although anthropologists, especially from Europe, used to apply these terms to all tribal cultures, it has fallen into disfavor as demeaning and is, according to many anthropologists, not only inaccurate, but dangerous.

Survival International runs a campaign to stamp out media portrayal of indigenous peoples as 'primitive' or 'savages'.[63] Friends of Peoples Close to Nature considers not only that indigenous culture should be respected as not being inferior, but also sees their way of life as a lesson of sustainability and a part of the struggle within the "corrupted" western world, from which the threat stems.[64]

After World War I, however, many Europeans came to doubt the morality of the means used to "civilize" peoples. At the same time, the anti-colonial movement, and advocates of indigenous peoples, argued that words such as "civilized" and "savage" were products and tools of colonialism, and argued that colonialism itself was savagely destructive. In the mid 20th century, European attitudes began to shift to the view that indigenous and tribal peoples should have the right to decide for themselves what should happen to their ancient cultures and ancestral lands.

See also

- Collective rights

- Colonialism

- Disappeared Indigenous Women

- Ethnic minority

- Genocide of indigenous peoples

- Human rights

- The Image Expedition

- Indigenism

- Indigenous rights

- Indigenous intellectual property

- Intangible cultural heritage

- Indigenous Peoples Climate Change Assessment Initiative

- Isuma

- List of indigenous peoples

- List of ethnic groups

- List of active NGOs of national minorities

- Uncontacted peoples

- United Nations Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues

- Unrepresented Nations and Peoples Organization

- Virgin soil epidemic

- Environmental racism in Europe

References

- 1 2 Sanders, Douglas (1999). "Indigenous peoples: Issues of definition". International Journal of Cultural Property. 8: 4–13. doi:10.1017/S0940739199770591.

- ↑ Acharya, Deepak and Shrivastava Anshu (2008): Indigenous Herbal Medicines: Tribal Formulations and Traditional Herbal Practices, Aavishkar Publishers Distributor, Jaipur- India. ISBN 978-81-7910-252-7. p. 440

- ↑ Bodley 2008:2

- ↑ "indigene, adj. and n." OED Online. Oxford University Press, September 2016. Web. 22 November 2016.

- ↑ Mario Blaser, Harvey A. Feit, Glenn McRae, In the Way: Indigenous Peoples, Life Projects, and Development, IDRC, 2004, p.53

- ↑ Silke Von Lewinski, Indigenous Heritage and Intellectual Property: Genetic Resources, Traditional Knowledge, and Folklore, Kluwer Law International, 2004, pp.130-131

- ↑ Robert K. Hitchcock, Diana Vinding, Indigenous Peoples' Rights in Southern Africa, IWGIA, 2004, p.8 based on Working Paper by the Chairperson-Rapporteur, Mrs. Erica-Irene A. Daes, on the concept of indigenous people. UN-Dokument E/CN.4/Sub.2/AC.4/1996/2 (, unhchr.ch)

- ↑ S. James Anaya, Indigenous Peoples in International Law, 2nd ed., Oxford University press, 2004, p.3; Professor Anaya teaches Native American Law, and is the third Commission on Human Rights Special Rapporteur on the Human Rights and Fundamental Freedoms of Indigenous People

- ↑ Martínez-Cobo (1986/7), paras. 379-382,

- ↑ Judgment of the Sapporo District Court, Civil Division No. 3, 27 March 1997, in (1999) 38 ILM, p.419

- ↑ STUDY OF THE PROBLEM OF DISCRIMINATION AGAINST INDIGENOUS POPULATIONS, p.10, Paragraph 25, 30 July 1981, UN EASC

- ↑ State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, p.1 Archived 15 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ State of the World's Indigenous Peoples, Secretariat of Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, UN, 2009 Archived 15 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Coates 2004:12

- ↑ Hall, Gillette, and Harry Anthony Patrinos. Indigenous Peoples, Poverty and Human Development in Latin America. New York: Palgrave MacMillan, n.d. Google Scholar. Web. 11 Mar. 2013

- ↑ Old World Contacts/Colonists/Canary Islands. Ucalgary.ca (22 June 1999). Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ http://www.un.org/esa/socdev/unpfii/documents/5session_factsheet1.pdf

- ↑ "Indigenous issues". International Work Group on Indigenous Affairs. Retrieved 5 September 2005.

- ↑ Dean, Bartholomew 2009 Urarina Society, Cosmology, and History in Peruvian Amazonia, Gainesville: University Press of Florida ISBN 978-0-8130-3378-5

- ↑ "Civilization.ca-Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage-Culture". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. Government of Canada. 12 May 2006. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ↑ "Inuit Circumpolar Council (Canada)-ICC Charter". Inuit Circumpolar Council > ICC Charter and By-laws > ICC Charter. 2007. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ↑ "In the Kawaskimhon Aboriginal Moot Court Factum of the Federal Crown Canada" (PDF). Faculty of Law. University of Manitoba. 2007. p. 2. Retrieved 18 September 2009.

- ↑ "Words First An Evolving Terminology Relating to Aboriginal Peoples in Canada". Communications Branch of Indian and Northern Affairs Canada. 2004. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ "Terminology of First Nations, Native, Aboriginal and Métis" (PDF). Aboriginal Infant Development Programs of BC. 2009. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 July 2010. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ↑ "Aboriginal Identity (8), Sex (3) and Age Groups (12) for the Population of Canada, Provinces, Territories, Census Metropolitan Areas and Census Agglomerations, 2006 Census – 20% Sample Data". Census > 2006 Census: Data products > Topic-based tabulations >. Statistics Canada, Government of Canada. 06/12/2008. Retrieved 18 September 2009. Check date values in:

|date=(help) - ↑ "Assembly of First Nations - Assembly of First Nations-The Story". Assembly of First Nations. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ↑ "Civilization.ca-Gateway to Aboriginal Heritage-object". Canadian Museum of Civilization Corporation. 12 May 2006. Retrieved 2 October 2009.

- ↑ Brazil urged to protect Indians. BBC News (30 March 2005). Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ Brazil sees traces of more isolated Amazon tribes. Reuters.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees. "Refworld - World Directory of Minorities and Indigenous Peoples - Turkey : Assyrians". Refworld.

- ↑ Ranjan, Amitav (21 September 2003). "Sahib Singh wanted to visit Serbia to meet fellow Jats". The Indian Express (New Delhi). Retrieved 15 March 2016.

- ↑ "Natives in Russia's far east worry about vanishing fish". The Economic Times. India. Agence France-Presse. 25 February 2009. Retrieved 5 March 2011.

- ↑ Recognition at last for Japan's Ainu, BBC NEWS

- ↑ Blust, R. (1999), "Subgrouping, circularity and extinction: some issues in Austronesian comparative linguistics" in E. Zeitoun & P.J.K Li, ed., Selected papers from the Eighth International Conference on Austronesian Linguistics. Taipei: Academia Sinica

- ↑ Fox, James J.""Current Developments in Comparative Austronesian Studies"" (PDF). (105 KB). Paper prepared for Symposium Austronesia Pascasarjana Linguististik dan Kajian Budaya. Universitas Udayana, Bali 19–20 August 2004.

- ↑ Diamond, Jared M. ""Taiwan's gift to the world"" (PDF). (107 KB). Nature, Volume 403, February 2000, pp. 709–710

- ↑ Kuoni - Far East, A world of difference. Page 88. Published 1999 by Kuoni Travel & JPM Publications

- ↑ Pygmy human remains found on rock islands, Science | The Guardian

- ↑ Bartholomew Dean and Jerome Levi (eds.) At the Risk of Being Heard: Indigenous Rights, Identity and Postcolonial States University of Michigan Press (2003)

- ↑ Mabo v Queensland (No 2) (1992) 175 CLR 1 F.C. 92/014 "http://www.austlii.edu.au/au/cases/cth/HCATrans/1991/23.pdf"

- ↑ No 'indigenous', reiterates Shafique. bdnews24.com (18 June 2011). Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ Ministry of Chittagong Hill Tracts Affairs. mochta.gov.bd. Retrieved on 2012-03-28.

- ↑ INDIGENOUS PEOPLEChakma Raja decries non-recognition. bdnews24.com (28 May 2011). Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ 'Define terms minorities, indigenous'. bdnews24.com (27 May 2011). Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ Disregarding the Jumma. Himalmag.com. Retrieved on 2011-10-11.

- ↑ "Mission to Vietnam Advocacy Day (Vietnamese-American Meet up 2013) in the U.S. Capitol. A UPR report By IOC-Campa". Chamtoday.com. 14 September 2013. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 17 June 2014.

- ↑ Taylor, Philip (December 2006). "Economy in Motion: Cham Muslim Traders in the Mekong Delta" (PDF). The Asia Pacific Journal of Anthropology. The Australian National University. 7 (3): 238. doi:10.1080/14442210600965174. ISSN 1444-2213. Retrieved 3 September 2014.

- ↑ "Conclusions". Montagnard Human Rights Organization (MHRO). 2010. Archived from the original on 6 October 2012.

- ↑ Graham A. Cosmas. MACV: The Joint Command in the Years of Escalation, 1962-1967. Government Printing Office. pp. 145–. ISBN 978-0-16-072367-4.

- ↑ Oscar Salemink (2003). The Ethnography of Vietnam's Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization, 1850-1990. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 28–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2579-9.

- ↑ Oscar Salemink (2003). The Ethnography of Vietnam's Central Highlanders: A Historical Contextualization, 1850-1990. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 29–. ISBN 978-0-8248-2579-9.

- ↑ McElwee, Pamela (2008). "7 Becoming Socialist or Becoming Kinh? Government Policies for Ethnic Minorities in the Socialist Republic of Viet Nam". In Duncan, Christopher R. Civilizing the Margins: Southeast Asian Government Policies for the Development of Minorities. Singapore: NUS Press. p. 182. ISBN 978-9971-69-418-0.

- ↑ "RESOLUTIONS AND DECISIONS. WHA47.27 International Decade of the World's Indigenous People. The Forty-seventh World Health Assembly," (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Hanley, Anthony J. Diabetes in Indigenous Populations, Medscape Today

- ↑ Ohenjo, Nyang'ori; Willis, Ruth; Jackson, Dorothy; Nettleton, Clive; Good, Kenneth; Mugarura, Benon (2006). "Health of Indigenous people in Africa". The Lancet. 367 (9526): 1937. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68849-1.

- ↑ Health and Ethnic Minorities in Viet Nam, Technical Series No. 1, June 2003, WHO, p. 10

- ↑ Facts on Suicide Rates, First Nations and Inuit Health, Health Canada

- ↑ "Health of indigenous peoples". Health Topics A to Z. Retrieved 17 April 2011.

- ↑ Asch, Michael (2005). "Levi-Strauss and the Political: "the Elementary Structures of Kinship" and the Resolution of Relations between Indigenous People and Settler States.". Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 11 (3): 425. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9655.2005.00244.x.

- ↑ Little Bear, Leroy (July 2009). "Naturalizing Indigenous Knowledge: Synthesis Paper". Canadian Council on Learning: 1–28.

- ↑ Charles Theodore Greve (1904). Centennial History of Cincinnati and Representative Citizens, Volume 1. Biographical Publishing Company. p. 35. Retrieved 2013-05-22.

- ↑ See Oliphant v. Suquamish Indian Tribe, 435 U.S. 191 (1978); also see Robert Williams, Like a Loaded Weapon

- ↑ Survival International website – About Us/FAQ. Survivalinternational.org. Retrieved on 2012-03-28.

- ↑ "Friends of Peoples close to Nature website – Our Ethos and statement of principles". Archived from the original on 26 February 2009. Retrieved 23 January 2010. Retrieved from Internet Archive 13 December 2013.

Further reading

- African Commission on Human and Peoples’ Rights (2003). "Report of the African Commission's Working Group of Experts on Indigenous Populations/Communities" (PDF). ACHPR & IWGIA.

- Baviskar, Amita (2007). "Indian Indigeneitites: Adivasi Engagements with Hindu NAtionalism in India". In Marisol de la Cadena & Orin Starn. Indigenous Experience today. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-519-5.

- Bodley, John H. (2008). Victims of Progress (5th. ed.). Plymouth, England: AltaMira Press. ISBN 0-7591-1148-0.

- de la Cadena, Marisol; Orin Starn, eds. (2007). Indigenous Experience Today. Oxford: Berg Publishers, Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research. ISBN 978-1-84520-519-5.

- Clifford, James (2007). "Varieties of Indigenous Experience: Diasporas, Homelands, Sovereignties". In Marisol de la Cadena & Orin Starn. Indigenous Experience today. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-519-5.

- Coates, Ken S. (2004). A Global History of Indigenous Peoples: Struggle and Survival. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. ISBN 0-333-92150-X.

- Farah, Paolo D.; Tremolada Riccardo (2014). "Intellectual Property Rights, Human Rights and Intangible Cultural Heritage". Journal of Intellectual Property Law, Issue 2, Part I, Giuffre pp. 21-47. ISSN 0035-614X.

- Farah, Paolo D.; Tremolada Riccardo (2014). "Desirability of Commodification of Intangible Cultural Heritage: The Unsatisfying Role of IPRs". TRANSNATIONAL DISPUTE MANAGEMENT, Special Issues "The New Frontiers of Cultural Law: Intangible Heritage Disputes", Volume 11, Issue 2. ISSN 1875-4120.

- Henriksen, John B. (2001). "Implementation of the Right of Self-Determination of Indigenous Peoples" (PDF). Indigenous Affairs. 3/2001 (PDF ed.). Copenhagen: International Work Group for Indigenous Affairs. pp. 6–21. ISSN 1024-3283. OCLC 30685615. Retrieved 1 September 2007.

- Hughes, Lotte (2003). The no-nonsense guide to indigenous peoples. Verso. ISBN 1-85984-438-3.

- Howard, Bradley Reed (2003). Indigenous Peoples and the State: The struggle for Native Rights. DeKalb, Illinois: Northern Illinois University Press. ISBN 0-87580-290-7.

- Johansen. Bruce E. (2003). Indigenous Peoples and Environmental Issues: An Encyclopedia. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-32398-0.

- Martinez Cobo, J. (198). "United Nations Working Group on Indigenous Populations". Study of the Problem of Discrimination Against Indigenous Populations. UN Commission on Human Rights.

- Maybury-Lewis, David (1997). Indigenous Peoples, Ethnic Groups and the State. Needham Heights, Massachusetts: Allyn & Bacon. ISBN 0-205-19816-3.

- Merlan, Francesca (2007). "Indigeneity as Relational Identity: The Construction of Australian Land Rights". In Marisol de la Cadena & Orin Starn. Indigenous Experience today. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-519-5.

- Pratt, Mary Louise (2007). "Afterword: Indigeneity Today". In Marisol de la Cadena & Orin Starn. Indigenous Experience today. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-519-5.

- Tsing, Anna (2007). "Indigenous Voice". In Marisol de la Cadena & Orin Starn. Indigenous Experience today. Oxford, UK: Berg Publishers. ISBN 978-1-84520-519-5.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

| Look up indigenous in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Indigenous people. |

Institutions

- IFAD and indigenous peoples (International Fund for Agricultural Development, IFAD)

- IPS Inter Press Service News on indigenous peoples from around the world

- Indigenous Peoples Issues & Resources