Springfield, Massachusetts

| Springfield, Massachusetts | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| City | |||

| City of Springfield | |||

|

Skyline of Springfield in October 2009 | |||

| |||

| Nickname(s): The City of Firsts; The City of Progress;[1][2][3] The City of Homes; A City in the Forest;[4] Hoop City[5][5][6] | |||

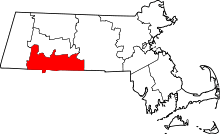

Location in Hampden County in Massachusetts | |||

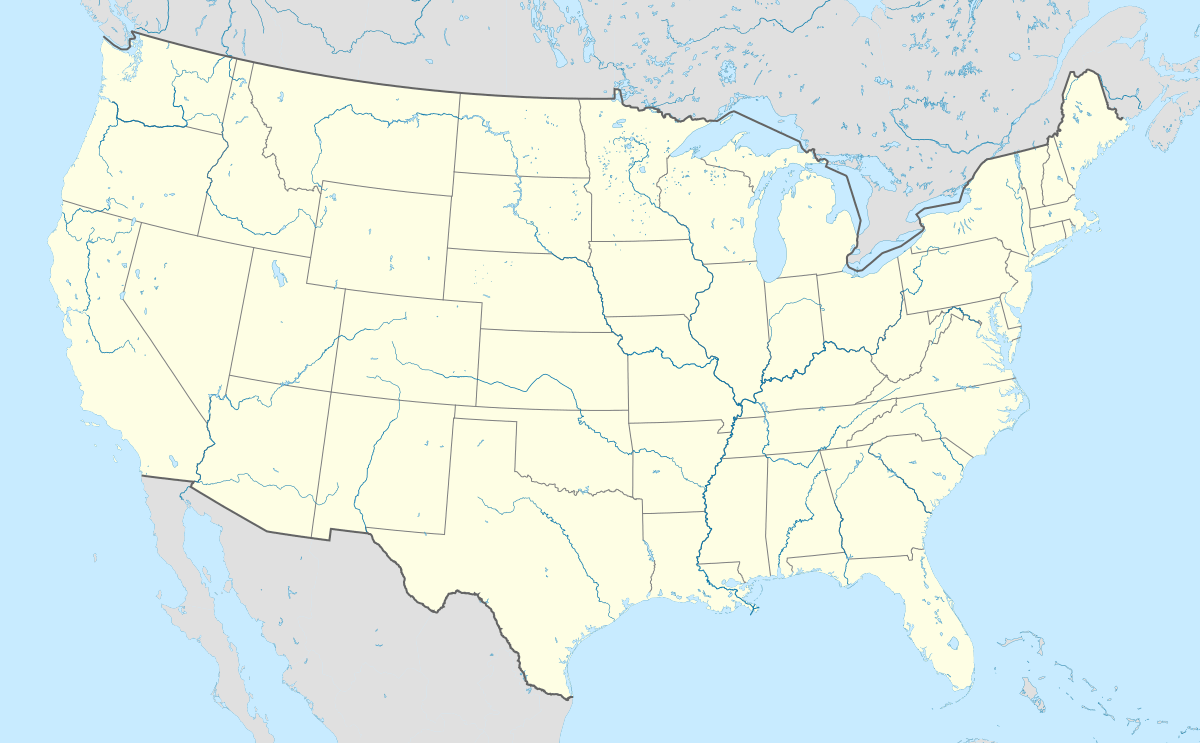

Springfield, Massachusetts Location in the United States | |||

| Coordinates: 42°06′05″N 72°35′25″W / 42.10139°N 72.59028°W | |||

| Country | United States | ||

| State | Massachusetts | ||

| County | Hampden | ||

| Settled | May 14, 1636 | ||

| Incorporated | 1852 | ||

| Founded by | William Pynchon | ||

| Government | |||

| • Type | Mayor-council city | ||

| • Mayor | Domenic Sarno (D) | ||

| Area | |||

| • City | 33.2 sq mi (86.0 km2) | ||

| • Land | 32.1 sq mi (83.1 km2) | ||

| • Water | 1.1 sq mi (2.9 km2) | ||

| Elevation | 70 ft (21 m) | ||

| Population (2010)[7] | |||

| • City | 153,060 | ||

| • Density | 4,768.2/sq mi (1,841.9/km2) | ||

| • Metro[8] | 698,903 | ||

| Time zone | Eastern (UTC-5) | ||

| • Summer (DST) | Eastern (UTC-4) | ||

| ZIP code | 01101, 01103–01105, 01107–01109, 01119, 01128–01129, 01151 | ||

| Area code(s) | 413 | ||

| FIPS code | 25-67000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 0609092 | ||

| Website |

www | ||

Springfield is a city in western New England, and the seat of Hampden County, Massachusetts, United States.[9] Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River near its confluence with three rivers: the western Westfield River, the eastern Chicopee River, and the eastern Mill River. As of the 2010 Census, the city's population was 153,060.[7] Metropolitan Springfield, as one of two metropolitan areas in Massachusetts (the other being Greater Boston), had an estimated population of 698,903 as of 2009.[8]

The first Springfield in the New World, it is the largest city in Western New England, and the urban, economic, and cultural capital of Massachusetts' Connecticut River Valley (colloquially known as the Pioneer Valley). It is the third-largest city in Massachusetts and fourth-largest in New England, after Boston, Worcester, and Providence. Springfield has several nicknames – The City of Firsts, because of its many innovations (see below for a partial list); The City of Homes, due to its Victorian residential architecture; and Hoop City, as basketball – one of the world's most popular sports[10] – was invented in Springfield by James Naismith.

Hartford, the capital of Connecticut, lies 23.9 miles (38 km) south of Springfield, on the western bank of the Connecticut River. Bradley International Airport, which sits 12 miles (19 km) south of Metro Center Springfield, is Hartford-Springfield's airport.[11][12][13] The Hartford-Springfield region is known as the Knowledge Corridor because it hosts over 160,000 university students and over 32 universities and liberal arts colleges – the second-highest concentration of higher-learning institutions in the United States.[14] The city of Springfield itself is home to Springfield College; Western New England University; American International College; and Springfield Technical Community College, among other higher educational institutions.

History

Springfield was founded in 1636 by English Puritan William Pynchon as "Agawam Plantation" under the administration of the Connecticut Colony. In 1641 it was renamed after Pynchon's hometown of Springfield, Essex, England, following incidents that precipitated the settlement joining the Massachusetts Bay Colony.[15] During its early existence, Springfield flourished as both an agricultural settlement and trading post, although its prosperity waned dramatically during (and after) King Philip's War in 1675, when natives laid siege to it and burned it to the ground.

The original settlement – today's downtown Springfield – was located atop bluffs at the confluence of four rivers, at the nexus of trade routes to Boston, Albany, New York City, and Montreal, and with some of the northeastern United States' most fertile soil.[16] In 1777, Springfield's location at numerous crossroads led George Washington and Henry Knox to establish the United States' National Armory at Springfield, which produced the first American musket in 1794, and later the famous Springfield rifle.[17] From 1777 until its closing during the Vietnam War, the Springfield Armory attracted skilled laborers to Springfield, making it the United States' longtime center for precision manufacturing.[18] The near-capture of the U.S. Arsenal at Springfield during Shays Rebellion of 1787 led directly to the formation of the U.S. Constitutional Convention.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, Springfielders produced many innovations, including the first American-English dictionary (1805, Merriam Webster); the first use of interchangeable parts and the assembly line in manufacturing (1819, Thomas Blanchard); the first American horseless car (1825, Thomas Blanchard); the discovery and patent of vulcanized rubber (1844, Charles Goodyear); the first American gasoline-powered car (1893, Duryea Brothers); the first successful motorcycle company (1901, "Indian"); one of America's first commercial radio stations (1921, WBZ, broadcast from the Hotel Kimball); and most famously, the world's second-most-popular sport, basketball (1891, Dr. James Naismith).[17]

Springfield underwent a protracted decline during the second half of the 20th century, due largely to the decommission of the Springfield Armory in 1969; poor city planning decisions, such as the location of the elevated I-91 along the city's Connecticut Riverfront; and overall decline of industry throughout the northeastern U.S. During the 1980s and 1990s, Springfield developed a national reputation for crime, political corruption and cronyism, which stands in stark contrast to the reputation it enjoyed throughout much of U.S. history. During early 21st century, Springfield sought to overcome its downgrade in reputation via long-term revitalization projects and undertook several large, but unfinished projects, including a $1 billion high-speed rail (New Haven-Hartford-Springfield high-speed rail;)[19] a proposed $1 billion MGM Casino;[20] and various other construction and revitalization projects.[21]

Geography

Springfield is located at 42°6′45″N 72°32′51″W / 42.11250°N 72.54750°W (42.112411, −72.547455).[22] According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 33.2 square miles (86 km2), of which 32.1 square miles (83 km2) is land and 1.1 square miles (2.8 km2) (3.31%) is water. Once nicknamed "The City in a Forest," Springfield features over 4.0 square miles (10.4 km2) of urban parkland, (which equals 12% of its total land area.)[23]

Located in the fertile Connecticut River Valley, surrounded by mountains, bluffs, and rolling hills in all cardinal directions, Springfield sits on the eastern bank of the Connecticut River, near its confluence with two major tributary rivers – the western Westfield River, which flows into the Connecticut opposite Springfield's South End Bridge; and the eastern Chicopee River, which flows into the Connecticut less than 0.5 square miles (1.3 km2) miles north of Springfield, in the city of Chicopee, (which constituted one of Springfield's most populous neighborhoods until it separated and became an independent municipality in 1852.)[24] The Connecticut state-line sits only 4 miles (6 km) south of Springfield, beside the wealthy suburb of Longmeadow, which itself separated from Springfield in 1783.[24]

Springfield's densely urban Metro Center district surrounding Main Street is relatively flat, and follows the north-south trajectory of the Connecticut River; however, as one moves eastward, the city becomes increasingly hilly.

Aside from its rivers, Springfield's 2nd most prominent topographical feature is the city's 735 acres (297 ha) Forest Park, designed by renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted. Forest Park lies in the southwestern corner of the city, surrounded by Springfield's attractive garden districts, Forest Park and Forest Park Heights, which feature over 600 Victorian Painted Lady mansions. Forest Park also borders Western Massachusetts' most affluent town, Longmeadow, Massachusetts. Springfield shares borders with other well-heeled suburbs such as East Longmeadow, Wilbraham, Ludlow and the de-industrializing city of Chicopee. The small cities of Agawam and West Springfield, Massachusetts lie less than a mile (1.6 km) from Springfield's Metro Center, across the Connecticut River.

The City of Springfield also owns the Springfield Country Club, which is located in the autonomous city of West Springfield, Massachusetts, the latter of which separated from Springfield in 1774.[24]

Climate

Springfield, like other cities in southern New England, has a humid continental climate (Köppen: Dfa) with four distinct seasons and precipitation evenly distributed throughout the year. Winters are cold with a daily average in January of around 26 °F (−3 °C). During winter, nor'easter storms can drop significant snowfalls on Springfield and the Connecticut River Valley. Temperatures below 0 °F (−18 °C) can occur each year, though the area does not experience the high snowfall amounts and blustery wind averages of nearby cities such as Worcester, Massachusetts and Albany, New York.

Springfield's summers are very warm and sometimes humid. During summer, several times per month, on hot days afternoon thunderstorms will develop when unstable warm air collides with approaching cold fronts. The daily average in July is around 74 °F (23 °C). Usually several days during the summer exceed 90 °F (32 °C), constituting a "heat wave." Spring and fall temperatures are usually pleasant, with mild days and crisp, cool nights. Precipitation averages 46.7 inches (1,186 mm) annually, and snowfall averages 49 inches (124 cm), most of which falls from mid-December to early March. Although not unheard of, extreme weather events like hurricanes and tornadoes occur infrequently in Springfield compared with other areas in the country. On the occasions that hurricanes have hit New England, Springfield's inland, upriver location has caused its damages to be considerably less than shoreline cities like New Haven, Connecticut and Providence, Rhode Island.

On June 1, 2011, Springfield was directly hit by the second-largest tornado ever to hit Massachusetts.[25] With wind speeds exceeding 160 mph (257 km/h), the 2011 Springfield tornado left 4 dead, hundreds injured, and over 500 homeless in the City of Springfield alone.[26][27] The tornado caused hundreds of millions of dollars worth of damage to Springfield and destroyed nearly everything in a 39-mile (63 km) path from Westfield, Massachusetts to Charlton, Massachusetts.[25] It was the first deadly tornado to strike Massachusetts since May 29, 1995.

| Climate data for Bradley International Airport, Connecticut (1981–2010 normals,[lower-alpha 1] extremes 1905–present)[lower-alpha 2] | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 72 (22) |

73 (23) |

89 (32) |

96 (36) |

99 (37) |

100 (38) |

103 (39) |

102 (39) |

101 (38) |

91 (33) |

83 (28) |

76 (24) |

103 (39) |

| Mean maximum °F (°C) | 55.6 (13.1) |

57.4 (14.1) |

70.1 (21.2) |

82.9 (28.3) |

89.0 (31.7) |

92.8 (33.8) |

95.1 (35.1) |

94.1 (34.5) |

88.7 (31.5) |

79.4 (26.3) |

70.8 (21.6) |

59.0 (15) |

97.2 (36.2) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 34.5 (1.4) |

38.5 (3.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

60.5 (15.8) |

71.2 (21.8) |

79.6 (26.4) |

84.5 (29.2) |

82.7 (28.2) |

74.9 (23.8) |

63.1 (17.3) |

51.6 (10.9) |

39.7 (4.3) |

60.7 (15.9) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 17.7 (−7.9) |

20.9 (−6.2) |

27.9 (−2.3) |

38.4 (3.6) |

47.7 (8.7) |

57.3 (14.1) |

62.7 (17.1) |

61.1 (16.2) |

52.7 (11.5) |

41.1 (5.1) |

33.2 (0.7) |

23.4 (−4.8) |

40.3 (4.6) |

| Mean minimum °F (°C) | −2 (−19) |

1.9 (−16.7) |

10.7 (−11.8) |

26.2 (−3.2) |

33.5 (0.8) |

44.2 (6.8) |

51.5 (10.8) |

48.4 (9.1) |

37.8 (3.2) |

26.9 (−2.8) |

17.5 (−8.1) |

6.0 (−14.4) |

−4.5 (−20.3) |

| Record low °F (°C) | −26 (−32) |

−24 (−31) |

−6 (−21) |

9 (−13) |

28 (−2) |

37 (3) |

44 (7) |

36 (2) |

30 (−1) |

17 (−8) |

1 (−17) |

−18 (−28) |

−26 (−32) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 3.23 (82) |

2.89 (73.4) |

3.62 (91.9) |

3.72 (94.5) |

4.35 (110.5) |

4.35 (110.5) |

4.18 (106.2) |

3.93 (99.8) |

3.88 (98.6) |

4.37 (111) |

3.89 (98.8) |

3.44 (87.4) |

45.85 (1,164.6) |

| Average snowfall inches (cm) | 12.3 (31.2) |

11.0 (27.9) |

6.4 (16.3) |

1.4 (3.6) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

0 (0) |

2.0 (5.1) |

7.4 (18.8) |

40.5 (102.9) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.01 inch) | 10.8 | 9.7 | 11.5 | 11.2 | 12.8 | 12.2 | 10.4 | 10.0 | 9.8 | 10.2 | 10.7 | 10.7 | 130.0 |

| Average snowy days (≥ 0.1 inch) | 5.8 | 4.7 | 3.5 | 0.5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0.9 | 4.7 | 20.1 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 63.9 | 63.0 | 60.4 | 58.0 | 63.0 | 67.3 | 68.0 | 70.6 | 72.9 | 69.2 | 68.3 | 68.0 | 66.0 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 169.8 | 176.1 | 213.9 | 228.2 | 258.6 | 273.4 | 293.1 | 269.6 | 223.6 | 199.4 | 139.4 | 139.5 | 2,584.6 |

| Percent possible sunshine | 58 | 59 | 58 | 57 | 57 | 60 | 64 | 63 | 60 | 58 | 47 | 49 | 58 |

| Source: NOAA (relative humidity and sun 1961–1990)[29][30][31] | |||||||||||||

Neighborhoods

The City of Springfield is divided into 17 distinct neighborhoods; in alphabetical order, they are:

- Bay – features Blunt Park. In terms of demographics, Bay is primarily African American.

- Boston Road – features the Eastfield Mall. Primarily commercial in character, it features shopping plazas designed for automobile travel.

- Brightwood – features numerous Baystate Health specialty buildings. Amputated from the rest of Springfield by the Interstate 91 elevated highway, academic suggestions are being made to reunite the neighborhood with the city.[32][33]

- East Forest Park – features Cathedral High School. Primarily upper-middle class residential in character. Borders East Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

- East Springfield – features Smith & Wesson and the Performance Food Group. Residential and working-class in character.

- Forest Park – features Frederick Law Olmsted's renowned 735 acres (3.0 km2) Forest Park and the Forest Park Heights Historic District, (established 1975).[34] Residential in character, featuring a commercial district at "The X" and an upper-class garden district surrounding Olmsted's park.

- Indian Orchard – features a well-defined Main Street and historic mill buildings that have become artists' spaces. Formerly a suburb of Springfield, Indian Orchard developed separately as a milltown on the Chicopee River before joining Springfield. Primarily residential in character, Indian Orchard features Lake Lorraine State Park, Hubbard Park, and weekly farmers markets.[35]

- Liberty Heights – features Springfield's three nationally ranked hospitals: Baystate Health, Mercy Medical, and Shriner's Children's Hospital. Primarily residential and medical in character, it features a demographically diverse population. Liberty Heights includes eclectic districts like Hungry Hill and Atwater Park, and Springfield's 3rd largest park, Van Horn Park.

- The McKnight Historic District – features the Knowledge Corridor's largest array of historic, Victorian architecture, including over 900 Painted Ladies. Primarily residential in character, McKnight was the United States' first planned residential neighborhood.[17] McKnight's commercial district is called Mason Square. Features American International College. In terms of demographics, McKnight features significant populations of African American and LGBT residents.

- Memorial Square – features the North End's commercial district.

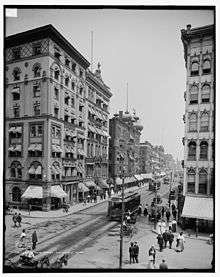

- Metro Center – features nearly all major cultural venues in the region.[36] Commercial, cultural, civic, and increasingly residential in character. Features the Downtown Business District, The Club Quarter – with over 60 clubs, restaurants, and bars – numerous festivals, cultural institutions, educational institutions, and significant historic sites.

- North End – not technically a Springfield neighborhood, but rather three northern Springfield neighborhoods. Includes Brightwood, which is residential and medical in character, but cut off from the rest of the city by Interstate 91; Memorial Square, which is commercial in character; and Liberty Heights, which is medical and residential in character. In terms of demographics, the North End is predominantly Puerto Rican.

- Old Hill – features Springfield College. Residential in character. Bordering Lake Massasoit. Old Hill is primarily Latino.[37]

- Pine Point – features the headquarters of MassMutual, a Fortune 100 company. Primarily middle-class and residential in character.

- Six Corners – features Mulberry Street in the Ridgewood Historic District (established 1977;)[38] the Lower Maple Historic District (established 1977;)[39] and the Maple Hill Historic District, (established 1977).[40] Urban and residential in character.

- Sixteen Acres – features Western New England University and SABIS International School. Suburban in character. Includes much of Springfield's post-World War II suburban architecture.

- South End – features numerous Italian-American restaurants, festivals, and landmarks. Urban and commercial in character, this neighborhood was hard hit by the June 1, 2011 tornado. Includes the Naismith Memorial Basketball Hall of Fame; however, it is separated from it by Interstate 91.

- Upper Hill – features Wesson Park. Bordering Lake Massasoit. Residential in character. Located between Springfield College and American International College.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 1,574 | — | |

| 1800 | 2,312 | 46.9% | |

| 1810 | 2,767 | 19.7% | |

| 1820 | 3,914 | 41.5% | |

| 1830 | 6,784 | 73.3% | |

| 1840 | 10,985 | 61.9% | |

| 1850 | 11,766 | 7.1% | |

| 1860 | 15,199 | 29.2% | |

| 1870 | 26,703 | 75.7% | |

| 1880 | 33,340 | 24.9% | |

| 1890 | 44,179 | 32.5% | |

| 1900 | 62,059 | 40.5% | |

| 1910 | 88,926 | 43.3% | |

| 1920 | 129,614 | 45.8% | |

| 1930 | 149,900 | 15.7% | |

| 1940 | 149,554 | −0.2% | |

| 1950 | 162,399 | 8.6% | |

| 1960 | 174,463 | 7.4% | |

| 1970 | 163,905 | −6.1% | |

| 1980 | 152,319 | −7.1% | |

| 1990 | 156,983 | 3.1% | |

| 2000 | 152,082 | −3.1% | |

| 2010 | 153,060 | 0.6% | |

| Est. 2015 | 154,341 | [41] | 0.8% |

| : * population estimate. [42] [43][44] | |||

As of the 2010 Census, there were 153,060 people residing in the City of Springfield. This figure does not include many of the 17,000-plus undergraduate and graduate university students who reside in Springfield during the academic year.

According to the 2010 Census, there were 61,706 housing units in Springfield, of which 56,752 were occupied. This was the highest average of home occupancy among the four, distinct Western New England metropolises, (the other three being Hartford, New Haven, and Bridgeport, Connecticut.) Also, as of 2010, Springfield features the highest average home owner occupancy ratio among the four Western New England metropolises at 50% – 73,232 Springfielders live in owner-occupied units, versus 74,111 in rental units. By comparison, as of the 2010 Census, New Haven features an owner occupancy rate of 31%; Hartford of 26%; and Bridgeport of 43%.[45]

According to the 2010 Census, Springfield had a population of 153,060, of which 72,573 (47.4%) were male and 80,487 (52.6%) were female. In terms of age, 73.0% were over 18 years old and 10.9% were over 65 years old; the median age is 32.2 years. The median age for males is 30.2 years and 34.1 years for females.

In terms of race and ethnicity, Springfield is 51.8% White, 22.3% Black or African American, 0.6% American Indian and Alaska Native, 2.4% Asian (1.2% Vietnamese), 0.1% Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander, 18.0% from Some Other Race, and 4.7% from Two or More Races (1.5% White and Black or African American; 1.0% White and Some Other Race). Hispanics and Latinos of any race made up 38.8% of the population (33.2% Puerto Rican).[46] Non-Hispanic Whites were 36.7% of the population in 2010,[47] down from 84.1% in 1970.[48]

Income

Data is from the 2009–2013 American Community Survey 5-Year Estimates.[49][50][51]

| Rank | ZIP Code (ZCTA) | Per capita income |

Median household income |

Median family income |

Population | Number of households |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Massachusetts | $35,763 | $66,866 | $84,900 | 6,605,058 | 2,530,147 | |

| 1 | 01128 | $33,573 | $78,864 | $86,964 | 2,468 | 964 |

| United States | $28,155 | $53,046 | $64,719 | 311,536,594 | 115,610,216 | |

| 2 | 01129 | $26,752 | $61,435 | $67,083 | 7,505 | 2,892 |

| Hampden County | $25,817 | $49,094 | $61,474 | 465,144 | 177,990 | |

| 3 | 01119 | $21,261 | $46,055 | $58,458 | 13,962 | 4,831 |

| 4 | 01108 | $18,347 | $34,064 | $35,083 | 25,755 | 9,348 |

| Springfield | $18,133 | $34,311 | $39,535 | 153,428 | 55,894 | |

| 5 | 01104 | $17,307 | $32,273 | $39,475 | 23,083 | 8,884 |

| 6 | 01103 | $17,095 | $14,133 | $17,457 | 2,556 | 1,553 |

| 7 | 01151 | $16,169 | $30,043 | $28,415 | 9,134 | 3,410 |

| 8 | 01109 | $13,938 | $33,376 | $36,737 | 31,429 | 9,555 |

| 9 | 01107 | $12,440 | $21,737 | $29,199 | 11,271 | 3,920 |

| 10 | 01105 | $12,137 | $18,402 | $21,345 | 12,360 | 4,836 |

Economy

Springfield's Top Five Industries (in order, by number of workers) are: Trade and Transportation; Education and Health Services; Manufacturing; Tourism and Hospitality; and Government. Springfield is considered to have a "mature economy," which protects the city to a degree during recessions and inhibits it somewhat during bubbles.[52] Springfield is considered to have one of America's top emerging multi-cultural markets – the city features a 33% Latino population with buying power that has increased over 295% from 1990 to 2006. More than 60% of Hispanic Springfielders have arrived during the past 20 years.[53]

With 25 universities and colleges within a 15-mile (24 km) radius from Springfield, including several of America's most prestigious universities and liberal arts colleges, and more than six institutions within the city itself, the Hartford-Springfield metropolitan area has been dubbed the Knowledge Corridor by regional educators, civic authorities, and businessmen – touting its 32 universities and liberal arts colleges, numerous highly regarded hospitals, and nearly 120,000 students. The Knowledge Corridor universities and colleges provide the region with an educated workforce, which yields a yearly GDP of over $100 billion – more than at least 16 U.S. States. Hartford-Springfield has become home to a number of biotech firms and high-speed computing centers. As of 2009 Springfield ranks as the 24th most important high-tech center in the United States with approximately 14,000 high-tech jobs.[54]

In 2010,[55] the median household income was $35,236. Median income for the family was $51,110. The per capita income was $16,863. About 21.3% of families and 26.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 40.0% of those under age 18 and 17.5% of those age 65 or over.

Business headquarters

The City of Springfield is the economic center of Western Massachusetts. It features the Pioneer Valley's largest concentration of retail, manufacturing, entertainment, banking, legal, and medical groups. Springfield is home to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts' largest Fortune 100 company, MassMutual Financial Group. It is also home to the world's largest producer of handguns, Smith & Wesson, founded in 1852. It is home to Merriam Webster, the first and most widely read American-English dictionary, founded in 1806. It also serves as the headquarters of the professional American Hockey League, the NHL's minor league, Peter Pan Bus, and Big Y Supermarkets, among other businesses.

Springfield is also home to the Commonwealth of Massachusetts' third largest employer, Baystate Health, with over 10,000 employees. Baystate is the western campus of Tufts University School of Medicine.[56] Baystate Health is in the midst of a $300 million addition – nicknamed "The Hospital of the Future," it is the largest construction project in New England.[57] In addition to Baystate, Springfield features two other nationally ranked hospitals; Mercy Medical, run by The Sisters of Providence, and Shriners Hospital for Children.

Companies headquartered in Springfield

- The American Hockey League – the primary development league for the NHL.

- Baystate Health – Largest employer and healthcare provider in Western Massachusetts; 3rd largest employer in Massachusetts, constructing the $300 million "Hospital of the Future."[57]

- Big Y – a regional supermarket chain that was originally founded in nearby Chicopee, but is now headquartered in Springfield. Big Y operates more than 50 supermarkets throughout Massachusetts and Connecticut.

- Breck Shampoo – Founded in Springfield in 1936.

- Fenton's Athletic Supplies – Sporting goods provider founded in 1924.

- Hampden Bank – Founded in Springfield in 1852. Headquartered in Springfield.

- Health New England

- Mutual Life Insurance Company – Founded in 1851. MassMutual is the second largest Fortune 100 company based in Massachusetts (2010 list). The corporate headquarters are on State Street.

- Merriam-Webster – Publisher of the original Webster Dictionary[58]

- NuVo Bank – Founded in 2008. Headquartered in Springfield.

- Peter Pan Bus Lines – Headquartered in Metro Center, Peter Pan will move its headquarters to Union Station upon its renovation in 2013.

- Smith & Wesson – Founded in 1852, Smith & Wesson is America's largest producer of handguns. The company maintains its corporate headquarters on Roosevelt Avenue in East Springfield.

Companies formerly in Springfield

- Forbes & Wallace – Regional department store, closed in 1974

- Friendly Ice Cream Corporation – Founded in Springfield, headquartered in the Springfield suburb of Wilbraham, Massachusetts.

- Good Housekeeping Magazine – Founded in Springfield in 1885.

- Indian Motocycle Manufacturing Company – America's first motorcycle brand, was founded by George M. Hendee and C. Oscar Hedström in Springfield in 1901

- Milton Bradley Company – American game company established in 1860. Headquartered in Springfield until its relocation to suburban East Longmeadow, Massachusetts.

- M-1 Rifle – productions started in 1919

- Monarch Insurance – went bankrupt while constructing Springfield's tallest skyscraper, Monarch Place.

- Rolls-Royce – Rolls-Royce of America Inc. was formed in 1919 to meet the growing U.S. luxury car market. A manufacturing plant was set up on Hendee Street in Springfield, Massachusetts, at the former 'American Wire Wheel Company' building. Over the years, the factory's 1,200 employees produced 1,703 Silver Ghosts and 1,241 Phantoms, with the first Silver Ghost chassis finished in 1921. The 1929 stock market crash led to the plant's closure in 1931.

- Sheraton Hotels and Resorts – founded in Springfield in 1937 with the purchase of The Stonehaven Hotel, and later the famous Hotel Kimball.

- Springfield Armory – Founded by George Washington in 1777; closed by the Pentagon in 1968.

Arts and culture

Amusement parks and fairs

Within two miles (3 km) of Springfield are New England's largest and most popular amusement park, Six Flags New England, and its largest and most popular fair, The Big E. Six Flags New England, located across Springfield's South End Bridge in Agawam features Superman the Ride, a roller coaster that has ranked first or second every year since 2001 in the annual Golden Ticket Awards publication by Amusement Today. Six Flags New England also features a large water park, kid's rides, and an outdoor concert stadium, among numerous other attractions. It opens in mid-April and closes at the end of October.

The Eastern States Exposition ("The Big E") is located across Springfield's Memorial Bridge in West Springfield. The Big E serves as the New England states' collective state fair. The Big E is currently the sixth largest agricultural fair in America and brings in thousands of tourists each September–October. The Big E features rides, carnival food, music, and replicas of each of the six New England state houses, each of which is owned by its respective New England state. During the Big E, these state houses serve as consulates for the six New England states, and also serve food for which the states are known.

Festivals

- Hoop City Jazz Festival: an annual event sponsored by the Springfield-headquartered Hampden Bank, which in the past has featured Springfield native and jazz legend Taj Mahal, the Average White Band, and others. In 2011 the Hoop City Jazz Festival will take place July 8–10 on Court Square, and will feature a jazz tribute to the City of New Orleans.

- Basketball Hall of Fame Enshrinement Weekend: a week of events that culminates in the Basketball Hall of Fame's enshrinement ceremony. It features numerous VIP galas, awards dinners, and press conferences.[59] Enshrinement takes place in Springfield's Neo-Classical Symphony Hall on Court Square. In 2011, Enshrinement Weekend will take place August 11–13.

- Armory Big Band Concerts: annually each summer the Springfield Armory National Park and National Historic Site features 1940s big band concerts. The band dresses in period costumes, and free dance lessons are provided. In 2011, an Armory Big Band Concert will be held on July 9.[60]

- Springfield Gay Pride Week: Springfield celebrated its first gay pride event June 8–16, 2011. Events range from political roundtables, to film showings, to celebrations at local gay clubs. According to 2010 Census statistics, Springfield has experienced a dramatic rise in its LGBT population during the last decade, and this celebration is aimed at increasing the visibility and voice of the LGBT community and its allies.[61]

- Our Lady of Mount Carmel Society Festival: in Springfield's Italian South End, it is long-running tradition to celebrate Italian Feast Days, in particular during the summer. The largest of these festivals is the Our Lady of Mount Carmel Society festival, which features a parade, and numerous food stands offering all sorts of Italian foods, e.g. fried dough, pasta with meatballs or sausages, sausage and peppers, meatball and steak grinders, and sugar cones, cotton candy, candy apples and gelato. The festival takes place each year in mid-July.

- Stearns Square Concert Series and Bike Nights: annually from June through September on Thursday evenings from 7 to 10pm, Springfield sponsors free live music at Stearns Square, in the heart of Metro Center's Club Quarter. Hundreds and sometimes thousands of motorcyclists attend Bike Nights, which coincide with the Stearns Square Concerts.

- Mattoon Street Arts Festival: one of the largest annual art festivals in Springfield. In 2011, it will feature a record number of exhibitors when it takes place from September 10–11, 2011 in the Mattoon Street Historic District. The art festival takes place at the corner of Mattoon and Chestnut Streets, near the Apremont Triangle and Kimball Towers Luxury Condominiums.[62]

- Pioneer Valley Jewish Film Festival: each spring the Pioneer Valley Jewish Film Festival presents two weeks of films, renowned guest speakers, and events related to Jewish culture. In 2011, the festival took place from March 23 – April 11.[63]

- St. Patrick's Day Parade: 7 miles (11 km) north of Springfield's Metro Center, the small city of Holyoke, Massachusetts stages the United States' 2nd-largest, annual St. Patrick's Day Parade (larger than Boston's and Chicago's, but slightly smaller than New York City's). In 2011, Holyoke's St. Patrick's Day Parade attracted over 400,000 revelers.[64]

- World's Largest Pancake Breakfast: annually, near the city's founding date (May 14) Springfield attempts to break the Guinness Book of World Records' mark for largest number of pancakes served. 2011's event drew over 30,000 people to Main Street, where approximately 60,000 pancakes were served.[65]

- Star Spangled Springfield: annually on July 4, Springfield stages an evening of patriotism, pageantry and pyrotechnics. The evening begins in Court Square with a patriotic concert by the Springfield Symphony Orchestra and concludes with an elaborate fireworks display from the Memorial Bridge. Numerous hills and bluffs in Springfield afford views of the fireworks.

- Caribbean Festival: in general held in late August each year, Springfield's Caribbean Festival celebrates the culture of the West Indies, which has increased greatly in Springfield during recent years. Highlights of the festival include a parade, dancers, floats, Caribbean music, and even a fashion show celebrating traditional Caribbean-dress.[66]

- The Parade of Big Balloons: since 1991, the Parade of Big Balloons has helped to usher in the holiday season in Springfield. A 75-foot (23 m) inflatable "Cat in the Hat" and a dozen or more big balloons, bands, and colorful marching contingents parade through Springfield's Metro Center at 11 am on the day after Thanksgiving. The Parade of Big Balloons starts in the city's North End and make its way down Main Street to the South End, entertaining crowds estimated at 75,000. In general, this parade is broadcast by local TV and radio affiliates.

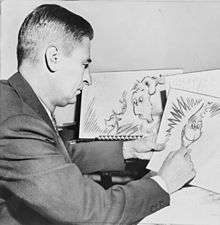

- Bright Nights: during the holiday season, over 600,000 lights illuminate a 2.5-mile (4.0 km) driving tour of Frederick Law Olmsted's Forest Park. Since its inception in the 1990s, the event has become a national attraction. From the new "Poinsettia Fantasy" entry to the giant Poinsettia Candles marking the exit, passengers in cars, vans, buses and campers drive by and through lighting displays including "Seuss Land," a display approved by the estate of Dr. Seuss, "Spirit of the Season," "Noah's Ark," "Victorian Village," "Barney Mansion," "Winter Woods," "North Pole Village," "Toy Land," and "Season's Greetings."

Museums

Springfield is home to five distinct museums at the Quadrangle, along with the ornate Springfield Public Library – an architecturally significant example of the City Beautiful movement. The Quadrangle's five distinct collections include the first American-made planetarium, designed and built (1937) by Frank Korkosz; the Dr Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden; the largest collection of Chinese cloisonne outside of China; and the original casting of Augustus Saint Gaudens's most famous sculpture, Puritan.

The Quadrangle's five museums are the Museum of Fine Arts, which features a large Impressionist collection; the George Walter Vincent Smith Art Museum, a collection of Asian curiosities; the Springfield Science Museum, which features a life-size Tyrannosaurus Rex, and aquarium, and the United States' first planetarium; the Connecticut Valley Historical Museum, which, as visitors find out, is inextricably linked with American History; and the Museum of Springfield History, a museum about the multi-faceted city.[67]

Springfield's Indian Orchard neighborhood is home to the RMS Titanic Historical Society's Titanic Museum. Unlike Springfield's urban Quadrangle museums, the setting for Indian Orchard's Titanic Museum looks like 1950s suburbia. Inside 208 Main Street is displayed a collection of rare artifacts that tell stories about the ill-fated ocean liner's passengers and crew.[68]

Music

Classical music aficionados hold the progressive Springfield Symphony Orchestra in high esteem. The Springfield Symphony Orchestra performs in Springfield Symphony Hall, a venue known for its ornate, Greek Revival architecture and "perfect acoustics." The SSO's conductor is Kevin Rhodes.

Famous musicians from Springfield include blues legend Taj Mahal; the band Staind and its frontman Aaron Lewis; Linda Perry, former leader singer of 4 Non Blondes and now famous songwriter and producer; Taj Mahal's sister, Carole Fredericks, a soul singer very popular in France; numerous jazz musicians, including Joe Morello, drummer for the Dave Brubeck Quartet; Phil Woods, saxophonist for Quincy Jones; Tony MacAlpine, keyboardist and guitarist with Steve Vai; and Paul Weston, composer for Frank Sinatra, among many others.

In 2011, Springfield's music scene was eclectic. It featured a notable heavy rock scene, from which the bands Gaiah, Staind, All That Remains, Shadows Fall, and The Acacia Strain rose to national prominence. Jazz and blues rival rock in popularity. Each summer, the Springfield-headquartered Hampden Bank sponsors the annual Hoops City Jazz & Art Festival, a three-day event that draws approximately 30,000 people to Metro Center to hear varieties of different jazz music – from smooth jazz, to hard bop, to New Orleans-style jazz. Headliners have included Springfield great Taj Mahal, the Average White Band, and Poncho Sanchez.

Fifteen miles north in the college towns of Northampton and Amherst, there is an active independent and alternative rock scene. Many of these bands perform regularly in Springfield's Club Quarter, at venues such as Fat Cats Bar & Grille, Theodore's, and the restored Paramount Theater. In the Club Quarter, centered on Stearns Square, nightly offerings include blues, college rock, jazz, indie, hip-hop, jam band, Latin, hard rock, pop, metal, karaoke, piano bars and DJs.

Each Thursday during the summer, a free concert is held at Stearns Square to coincide with Bike Night, a happening that in general attracts thousands of motorcyclists to the Quarter and thousands more spectators to hear live music.

Larger rock and hip-hop acts play at the 7,000-seat MassMutual Center. The arena has played host to artists such as Marilyn Manson, Alice Cooper, Nirvana, David Bowie, David Lee Roth, Poison, Pearl Jam, and Bob Dylan.

Nightlife

The City of Springfield' Club Quarter is the nightlife capital of the Pioneer Valley and the Knowledge Corridor, featuring approximately 60 dance clubs, bars, music venues, LGBT venues, and after-hours establishments. In general, most clubs, bars, music venues, and other nightspots are located on or near upper Worthington Street, on and around Stearns Square, or on Chestnut Street.

Springfield's Club Quarter features a large (and growing) LGBT nightlife scene at establishments like Oz (397 Dwight Street), Pure (324 Chestnut Street), The Pub Lounge (382 Dwight Street), and Club Xtatic (240 Chesnut Street, featuring dancers). In 2011, LGBT magazine The Advocate ranked Springfield No. 13 among its "New Gay American Cities," ahead of San Diego and Albuquerque, New Mexico. There has been a notable increase in Springfield's LGBT nightlife since Massachusetts legalized gay marriage in 2004.

Points of interest

- Basketball Hall of Fame – housed in a $47 million structure designed by Gwathmey Siegel & Associates, it is a shrine to the world's second most popular sport, basketball. Located in the city where basketball was invented, the facility – built beside the Connecticut River – spans 80,000 square feet (7,400 m2) features numerous restaurants and the WMAS-FM studios. However, it is separated from Springfield's Metro Center by the 8-lane highway, Interstate 91.

- The Big E – also known as The Eastern States Exposition, it is New England's collective, annual state fair. Held on a permanent fairgrounds approximately 1.5 miles (2.4 km) west of Springfield's Metro Center, across the ornate Memorial Bridge in West Springfield, it attracts more than 1 million visitors per year during its 14- to 17-day run beginning in mid-September.

- Bright Nights – during the holiday season, Forest Park hosts a nationally renowned, 2+ mile, state-of-the-art lighting extravaganza. Year over year, the numerous lighting displays become creative and elaborate.

- City Stage – Springfield's best-known playhouse features off-Broadway productions, comedians, and children's programming.

- Club Quarter – a grouping of 60 clubs, bars, and restaurants around Stearns Square, Worthington and Main Streets. Springfield's variety of nightclubs and entertainment is part of what makes it, according to Yahoo!, one of America's ten best cities for dating.[69] LGBT and dance clubs are integrated with hip-hop, rock, jazz, and blues clubs. Thursday, Friday, and Saturday are particularly busy evenings.

- Connecticut River Walk Park – a landscaped park that snakes along the Connecticut River, affording views of the Mount Tom Range, Mount Holyoke Range, and Springfield's skyline. However, this park is separated from Springfield by the badly designed, 8-lane Interstate 91 highway, which cuts through three Springfield riverfront neighborhoods, and thus presents a major obstacle to accessing this riverfront park. In 2010, the Urban Land Institute released a plan for Springfield's riverfront, which has given Springfielders cause for hope that Interstate 91 will either be moved or made more easily passable via new design features that would allow people to access the River Walk and the Basketball Hall of Fame.[70][71][72]

- Court Square – a park, referred to as "Springfield's front door," it remains the city's only topographical constant since its founding in 1636. Located on Main Street and surrounded by ornate architecture, including the iconic Springfield Municipal Group, Court Square is the civic heart of Springfield. Until the 1960s, Court Square extended to the Connecticut River; however, as with Olmsted's Forest Park, its connection to the river was severed by the building of the Interstate 91 elevated highway.

- Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden – amidst the Quadrangle, there are large, bronze statues of characters from Springfield native Dr. Seuss's books.

- First Game of Basketball Sculpture – located directly on the site of the first game of basketball, this illuminated sculpture in Springfield's Mason Square commercial district has become a site of pilgrimage for basketball fans from around the world.

- Forest Park – designed by Frederick Law Olmsted, the renowned landscape designer of New York City's Central Park, Springfield's Forest Park is nearly the same size as Central Park at 735 acres (297.4 ha). It features the Zoo at Forest Park; the 31 acres (12.5 ha) Porter Lake; numerous playgrounds; a formal rose garden; 38 tennis courts; a skating arena; numerous basketball and bocce courts; lawn bowling fields; Victorian promenades and water gardens; tree groves; baseball diamonds; numerous statues; an aquatic park; and the Barney Carriage House, where many weddings take place.

- King Philip's Stockade – an historic, city park where in 1675, the Pocumtuc Indians – organized by Chief Metacomet, also known as King Philip – initiated the Attack on Springfield during King Philip's War. During the attack, approximately 75% of the city was burned.

- MassMutual Center – formerly known as the Springfield Civic Center, this 8,000-seat arena and convention center received a $71 million renovation in 2003–2005. Located across from historic Court Square in Metro Center, the arena houses the American Hockey League's Springfield Thunderbirds. The venue also attracts big-name concert tours. In the past, it has hosted concerts by Nirvana, Pearl Jam, Van Halen, Marilyn Manson, The Eagles, and Bob Dylan, among many others.

- Mulberry Street – the street featuring the house that inspired Dr. Seuss's first children's book, the classic And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street.

- The Puritan – a famous statue designed by Augustus Saint-Gaudens depicting Deacon Samuel Chapin, an early settler of Springfield. "The Puritan" is perhaps St. Gaudens' most celebrated, outdoor sculpture. Originally located in Stearns Square, it has been located in Merrick Park in the Quadrangle for over 100 years and become a symbol of Springfield.

- The Quadrangle – a campus of five museums surrounding the Dr. Seuss National Memorial Sculpture Garden, is an extraordinary cultural grouping – especially considering Springfield's medium-size population and small land area. It includes the world-class Museum of Fine Arts, known for its Impressionist and Dutch Renaissance collections, as well as its extensive collection of American masters, including works by Springfielder James McNeill Whistler. The world-class Springfield Science Museum features the United States' first planetarium (built 1931), and a large dinosaur exhibit. The world-class George Walter Vincent Smith Museum is known worldwide for housing the largest collection of Chinese cloisonne outside of China; it also features exotic curiosities like Asian suits of armor, and a collection of marble busts. The Quadrangle also features two regional history museums: the Connecticut Valley Historical Society, which tells the story of "The Great River" and its people, and the new Museum of Springfield History, which showcases the innovations that make Springfield "The City of Progress" during the abolitionist period and Industrial Revolution, which includes the first American-English dictionary, the first gasoline-powered car, the first successful motorcycle company, the first modern fire engine, and dozens of other firsts (see below for a more complete list).

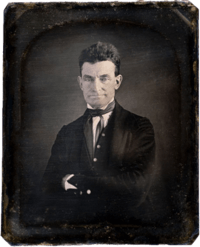

- St. John's Congregational Church – founded in 1844 as the Sanford Street "Free Church," St. John's Congregational Church is a predominately black church that played a pivotal role in the abolitionist movement. While living in Springfield, John Brown attended services here from 1846 to 1850, and as of 2011, the church still displays John Brown's Bible. It was at this church where John Brown met Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and other prominent abolitionists – and where he later founded the famous, militant League of Gileadites in response to the Fugitive Slave Act. As of 2011, St. John's remains one of the most prominent, predominately black congregations in the Northeastern United States.[73]

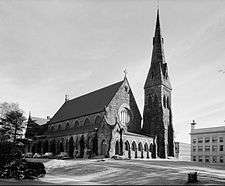

- St. Michael's Cathedral – beside the Quadrangle, this elegant Catholic Church is the seat of the Diocese of Greater Springfield.

- Stacy Building – the location where, in 1892–93, the Duryea Brothers built the first, American, gasoline-powered car, which in 1895 won the first automobile race in Chicago, Illinois. A model of the Duryea Brothers' first car sits in a tree-shaded park beside the historic location, amidst the restaurants and bars of the Club Quarter.

- Six Flags New England – located 1 mile (1.6 km) west of Springfield's South End in Agawam, this amusement park is the largest in the Northeast and features a top-ranked roller coaster, Superman the Ride.

- The Springfield Armory National Park – founded by General George Washington and Henry Knox in 1777; the site of Shays' Rebellion in 1787, which led directly to the U.S. Constitutional Convention; the site of numerous technological innovations including the manufacturing advances known as interchangeable parts, the assembly line, and mass production; and the producer of the United States Military's firearms from 1794 to 1968, when the Armory was controversially shut down by Defense Secretary Robert McNamara. Today, it is a National Park, National Historic Site, and features a museum that includes one of the world's largest collections of firearms.[74]

- Symphony Hall – dedicated in 1913 by President William Howard Taft as part of the Springfield Municipal Group, Springfield Symphony Hall features "perfect acoustics." It is home to the progressive Springfield Symphony Orchestra conducted by showman Kevin Rhodes, and also hosts numerous Broadway touring productions.

- Stearns Square – designed by the renowned artistic team of Stanford White and Augustus Saint-Gaudens in 1897, this small park is the center of Springfield's Club Quarter.[75] It features ornate architectural and sculptural details from the original team's design; however, most of those were meant to accompany The Puritan, and thus moved to storage. Stearns Square hosts a large motorcycle gathering each Thursday evening, and is the site of a summer concert series.

Sports

Besides Springfield's historic connection with basketball, the city has a rich sporting history. Volleyball was invented in the adjacent city of Holyoke, and the first exhibition match was held in 1896 at the International YMCA Training School, now known as Springfield College.

Ice hockey has been played professionally in Springfield since the 1920s, and Springfield is home to the league headquarters of the American Hockey League. The Springfield Indians of the American Hockey League (now located in Utica, New York) was the oldest minor league hockey franchise in existence. In 1994 the team relocated to Worcester and was replaced by the Springfield Falcons, who played at the MassMutual Center. The Falcons were then replaced by the Springfield Thunderbirds in 2016. For parts of two seasons (1978–80) the NHL Hartford Whalers played in Springfield while their arena was undergoing repairs after a roof collapse. On the amateur level, the Junior A Springfield Olympics played for many years at the Olympia, while American International College's Yellow Jackets compete in NCAA Division I hockey.

Basketball remains a popular sport in Springfield's sporting landscape. Prior to the 2014–15 season, Springfield was home to the Springfield Armor of the NBA Development League, which began play in 2009 at the MassMutual Center. Beginning in the 2011–2012 season, the Armor was the exclusive affiliate of the Brooklyn Nets.[76] For many years, the Hall of Fame Tip-Off Classic has been the semi-official start to the college basketball season, and the NCAA Division II championships are usually held in Springfield. The Metro Atlantic Athletic Conference will play its championships in Springfield from 2012 to 2014.[77] The New England Blizzard of the ABL played its first game in Springfield, and several minor pro men's and women's teams have called the city home, including the Springfield Fame of the United States Basketball League (the league's inaugural champion in 1985) and the Springfield Hall of Famers of the Eastern Professional Basketball League.

Springfield has had professional baseball in the past, and according to its current mayor, remains intent on pursuing it in the future.[78] The Springfield Giants of the Single– and Double-A Eastern League played between 1957 and 1965. The team was quite successful, winning consecutive championships in 1959, 1960 and 1961, by startling coincidence the same seasons in which the Springfield Indians won three straight Calder Cup championships in hockey. The Giants played at Pynchon Park by the Connecticut River until relocating after the 1965 season. Pynchon Park's grandstands were destroyed by fire the year after in 1966.[79] Before that time, the Springfield Cubs played in the minor league New England League from 1946 until 1949, after which the league folded; they then played in the International League until 1953. For many years before the Giants, Springfield was also a member of the Eastern League, between 1893 and 1943. In general, the team was named the Ponies, but it also carried the nicknames of "Maroons" (1895), "Green Sox" (1917), "Hampdens" (1920–21), "Rifles (1932, 1942–43) and "Nationals" (1939–41). The team located closest are the Valley Blue Sox of the New England Collegiate Baseball League who play their games in nearby Holyoke, but house their team offices at 100 Congress Street in Springfield.

Springfield has an official roller derby team: Pair O Dice City Roller Derby. They are a non-profit organization who uses their roller derby games as fundraisers for groups such as Dakin Animal Shelter and the Shriners. Pair O Dice skaters are featured on the Clean Up ads near the waterfront.

Architecture

In addition to its nickname The City of Firsts, Springfield is known as The City of Homes for its attractive architecture, which differentiates it from most medium-size, Northeastern American cities. Most of Springfield's housing stock consists of Victorian "Painted Ladies" (similar to those found in San Francisco;) however, Springfield also features Gilded Age mansions, urban condominiums buildings, brick apartment blocks, and more suburban post-World War II architecture (in the Sixteen Acres and Pine Point neighborhoods). While Springfield's architecture is attractive, much of its built-environment stems from the 19th and early 20th centuries when the city experienced a period of "intense and concentrated prosperity" – today, its Victorian architecture can be found in various states of rehabilitation and disrepair. As of 2011, Springfield's housing prices are considerably lower than nearby New England cities that do not feature such intricate architecture.

In Metro Center, some of Springfield's former hotels, factories, and other institutions have been converted into apartment buildings and luxury condominiums. For example, Springfield's ornate Classical High School (235 State Street), with its immense Victorian atrium – where Dr. Seuss, Timothy Leary, and Taj Mahal all went to high school – is now a luxury condominium building. The Hotel Kimball, (140 Chestnut Street), which hosted several U.S. Presidents as guests and once featured the United States' first commercial radio station (WBZ), has been converted into The Kimball Towers Condominiums.[80] The former McIntosh Shoe Company (158 Chestnut Street), one of Springfield's finest examples of the Chicago School of Architecture, has been converted into industrial-style condominiums; and the red-brick, former Milton Bradley toy factory is now Stockbridge Court Apartments (45 Willow Street). In the Ridgewood Historic District, the 1950s-futurist Mulberry House (101 Mulberry Street), is now a condominium building that features some of the finest views of Springfield.

Forest Park (and Forest Park Heights), surrounding Frederick Law Olmsted's beautiful 735 acres (297.4 ha) Forest Park, is a New England Garden District that features over 600 Victorian Painted Ladies. The McKnight National Historic District, America's first planned residential neighborhood, (1881), features over 900 Victorian Painted Ladies, many of which have been rehabilitated by Springfield's growing LGBT community. The Old Hill, Upper Hill, and Bay neighborhoods also feature this type of architecture.

Maple High, which is architecturally (and geographically) distinct from, but often included with Springfield's economically depressed Six Corners neighborhood, was Springfield's first "Gold Coast." Many mansions from the early 19th century and later gilded age stand atop a bluff on Maple Street, overlooking the Connecticut River. The Ridgewood Historic district on Ridgewood and Mulberry Streets also feature historic mansions from the 19th and early 20th centuries.

Springfield – like many mid-size Northeastern cities, e.g., Hartford, Albany, and New Haven – from the 1950s–1970s, razed a significant number of historic commercial buildings in the name of urban renewal. In 1961, this included Unity Church, the first building designed by the young Henry Hobson Richardson.[81] Springfield's Metro Center remains more aesthetically cohesive than many its peer cities; however, as elsewhere, the city currently features a patchwork of parking-lots and grand old buildings. Current efforts are underway to improve the cohesion of Springfield's Metro Center, including the completed Main Street and State Street Corridor improvement projects, the upcoming $70 million renovation to Springfield's 1926 Union Station and the renovation of the Epiphany Tower on State Street into a new hotel. New constructions include the architecturally award-winning, $57 million Moshe Safdie-designed Federal Building on State Street.[82]

Parks

In 2010, Springfield was cited as the 4th "Greenest City" in the United States – the largest city cited in the Top 10. The recognition noted Springfield's numerous parks, the purity of its drinking water, its regional recycling center, and organizations like ReStore Home Improvement Center, which salvages building materials.[83] Springfield features over 2,400 acres (10 km2) of parkland distributed among 35 urban parks, including the grand, 735 acres (297.4 ha) Forest Park. Well-known parks include the following, among others:

- Apremont Triangle Park is a triangular, pocket park in front of Springfield's historic Kimball Towers in Metro Center. Named for Springfield's 104th Infantry Regiment, which following the World War I Battle of Apremont, became the first U.S. military unit awarded for heroism by a foreign power, receiving France's highest military honor: the croix de guerre for bravery in combat. The same Springfield unit received the same honor again in World War II. Apremont Triangle Park, steps from both the bohemian Kimball Towers and upper-class Quadrangle-Mattoon Street Historic District offers a place to sit amidst the restaurants on the northern fringe of the Club Quarter.[84]

- Armoury Commons is a rectangular park just south of the Springfield Armory, located at the corner of Pearl and Spring Streets in Metro Center. Renovated in 2009, Armoury Commons features several sculptures, including Pynchon Park's original sculpture. The park is often used as a place to play chess and other games.

- Connecticut River Walk Park is a narrow, landscaped park that snakes along the scenic Connecticut River for several miles. Beginning near the Basketball Hall of Fame, it features jogging trails, benches, boat docks, and plazas – all of which afford scenic vistas of the Connecticut River and Connecticut River Valley. However, Interstate 91's position, height, and ancillary structures – including a 1756-car, below-grade parking lot, (the largest in the city, ) and 20-foot (6 m) stone walls block all views of the Connecticut River, and all but three passages to the park from Metro Center. Despite Springfield's rating as one of the most walkable cities in the U.S., due to the poor planning of I-91, this park can be difficult to reach on foot.[85]

- Court Square has been Springfield's one topographical constant since colonial days – it is located in Metro Center. Featuring monuments to Springfield's hero during King Philip's War of 1675, Miles Morgan; President William McKinley; and a Civil War memorial Court Square is surrounded by extraordinarily fine architecture, including H.H. Richardson's Richardsonian Romanesque Courthouse; the Springfield Municipal Group featuring the Greek Revival City Hall, Symphony Hall, and the 300-foot (91 m) Italianate Campanile; and also the 1819 reconstruction of the 1638 Old First Church. Other buildings included are the One Financial Plaza skyscraper, UMass Amherst's Urban Design Studio in the Byers Block (b. 1835;) and, across Main Street, the MassMutual Center arena and convention center.

- Five Mile Pond is a Naturalist park and pond approximately 5 miles (8 km) from Springfield's Metro Center in the Pine Point neighborhood of Springfield. There are several, glacial lakes in the Five Mile Pond area, including Lake Lorraine, Loon Pond, and Long Pond. Five Mile Pond is popular with boaters.

- Forest Park is one of the United States' largest urban parks (at 735 acres (297.4 ha)) and also one of its most historically important urban parks. Designed by Frederick Law Olmsted – the famed designer of New York City's Central Park – Forest Park is nearly as large, and similarly diverse. Amenities include the Zoo at Forest Park, which features many exotic animals; the United States' first public swimming pool (1899;) numerous playgrounds; an ice-skating rink; a formal rose garden; the 31 acres (12.5 ha) Porter Lake, which features fishing and paddle-boating; 38 tennis courts; numerous basketball and bocce courts; lawn bowling fields; Victorian promenades and water gardens; dozens of hiking and walking trails; an aquatic park; numerous sculptures; and the Carriage House of Springfielder Everett Hosmer Barney, the man who invented the ice skate and popularized the roller skate during the 19th century. During the holiday season, Forest Park hosts the nationally renowned lighting display, "Bright Nights."

- King Philip's Stockade is an historic park, famous as the site where Native Americans organized the 1675 Sack of Springfield; The Stockade features numerous picnic pavilions, excellent views of the Connecticut River Valley, and a sculpture of The Windsor Indian, who tried in vain to warn the residents of Springfield of coming danger.[86]

- Leonardo da Vinci Park is a small greenspace (0.4 acres), located in the historically Italian South End of Springfield. It features ornamental perimeter fencing surrounding a playground. Leonardo da Vinci Park was renovated in 2009 and now features new picnic tables and playground equipment.

- Pynchon Park is an architecturally interesting brutalist-style city park, which was dedicated in 1977. It links Springfield's Metro Center with the Quadrangle cultural grouping, (the museums and sculptures sit atop a steep bluff). Mostly made of poured concrete, but featuring a waterfall, lush greenery, and fountains, Pynchon Park received numerous accolades from the American Institute of Architecture for "enhancing the quality of the urban environment in the core of the city." It features two levels and a distinctive elevator.[78]

- Stearns Square is a rectangular park between Worthington Street and Bridge Street in Springfield's Club Quarter, located in Metro Center. Designed by the creative 'dream-team' of Stanford White and Augustus Saint-Gaudens. It was there that St. Gaudens' most famous work, The Puritan, originally stood. The Puritan has since been moved to the Quadrangle, at the corner of State and Chestnut Streets; however, White's and St. Gaudens' original fountain, bench, and turtle sculptures, all meant to compliment The Puritan, remain in Stearns Square.

- Van Horn Park is a large park in the Hungry Hill section of Liberty Heights in Springfield. It features two ponds and a reservoir. The Reservoir and lower dam are not generally accessible to the public. The Main Entrance is on Armory Street near Chapin Terrace.

Government

City of Springfield

The City of Springfield employs a strong mayor form of city government. Springfield's mayor is Mayor Domenic J. Sarno, who has been serving since 2008.

The city's governmental bureaucracy consists of 33 departments, which administer a wide array of municipal services, e.g. police, fire, public works, parks, public health, housing, economic development, and the Springfield Public School System, New England's 2nd largest public school system.[87]

Springfield's legislative body is its City Council, which features a mix of eight ward representatives—even though the city has more than double that number of neighborhoods, resulting in several incongruous "wards"—and five at-large city representatives, several of whom have served for well over a decade.

The Springfield Fire Department provides fire protection and emergency medical services to the city and holds the distinction of being one of the oldest established fire departments in the United States.[88]

Finances

In 2003, the City of Springfield was on the brink of financial default, and thus taken over by a Commonwealth-appointed Finance Control Board until 2009. Disbanded in June of that year, the Control Board made great strides stabilizing Springfield's finances.[89] While Springfield has achieved balanced budgets since 2009, the city has not enlarged its tax-base, and thus many of its public works projects — which have been in the pipeline for years, some even decades — remain unfinished, (e.g., repairs to Springfield's landmark Campanile.).[90] Springfield is being considered for a $800 million development project; MGM Springfield. To many this is an impressive feat given the natural disasters and continuous cuts to state aide during the Great Recession.

Construction for MGM Springfield is currently underway. It's expected to be completed and operational by the fall of 2018.

The city's finances have made great stride under Mayor Domenic J. Sarno's (2008–present) leadership; despite facing natural and man made disasters: June 1, 2011 tornado Springfield Tornado, Hurricane Irene, a freak October Snow Storm (which in some ways was more damaging than the tornado),[91] and a large gas explosion in the downtown area in 2012. The city managed the recoveries with great skill and has come out in great shape; even receiving a bond upgrade from Standard and Poor's Investment Services. In addition the City of Springfield has received the GFOA's Distinguished Budget Award for six consecutive years.

Judicial system

Like every other municipality in Massachusetts, Springfield has no judicial branch itself. Rather, it uses the Springfield-based state courts, which include Springfield district court and Hampden County Superior Court, both of which are based in Springfield. The Federal District Court also regularly hears cases in Springfield – now in an architecturally award-winning building on State Street, constructed in 2009.

Politics

Springfield became a city on May 25, 1852, by decree of the Massachusetts Legislature, after a decade-long internal dispute that resulted in the partition of Chicopee from Springfield, and thus the loss of 2/5 of the city's population.

Springfield, like all municipalities in Massachusetts, enjoys limited home rule. The current city charter, in effect since 1959, uses a "strong mayor" government with most power concentrated in the mayor, as in Boston and elsewhere. The mayor representing the city's executive branch presents the budget, appoints commissioners and department heads, and in general runs the city. The Mayor is former City Councilor Domenic Sarno, elected November 6, 2007 by a margin of 52.54% to 47.18% against incumbent Charles Ryan. He took office in January 2008. In November 2009 and 2011, Sarno won reelection, albeit — in the latter case — with just 22% of eligible Springfield voters voting.[92]

The Springfield City council, consisting of thirteen members, is the city's legislative branch. Elected every odd numbered year, eight of its members are elected to represent "wards," which are made of (sometimes incongruous) groupings of Springfield neighborhoods, e.g. Springfield's ethnic North End neighborhoods — Memorial Square and Brightwood — share a ward with Metro Center, Springfield's downtown. Five city council members are elected at-large. The City Council passes the city's budget, holds hearings, creates departments and commissions, and amends zoning laws.

The mayor's office and city council chambers are located in city hall – part of the Municipal Group in Metro Center, Springfield. The Finance Control Board met there as well.

| Voter Registration and Party Enrollment as of October 15, 2008[93] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Number of Voters | Percentage | |||

| Democratic | 44,148 | 52.21% | |||

| Republican | 7,734 | 9.15% | |||

| Unaffiliated | 32,035 | 37.88% | |||

| Minor Parties | 648 | 0.77% | |||

| Total | 84,565 | 100% | |||

Switch to ward representation

| Springfield City Councilors 2014–2015[94] |

|---|

|

In the past, efforts have been made to provide each of the city's eight wards a seat in the city council, instead of the current at-large format. There would still be some at-large seats under this format. The primary argument for this has been that City Councilors live in only four of the city's wards. An initiative to change the composition failed to pass the City Council twice. In 2007 Mayor Charles V. Ryan and City Councilor Jose Tosedo proposed a home-rule amendment that would expand the council to thirteen members adding four seats to the existing nine member at large system, but allocated between eight ward and five at large seats. This home-rule petition was adopted by the City Council 8–1, and was later passed by the State Senate and House and signed by the Governor. On election day, November 6, 2007, city residents voted overwhelmingly in favor of changing the City Council and School Committee. The ballot initiative that established a new council with five at-large seats and eight ward seats passed 3–1. On November 3, 2009, Springfield held first-in-a-generation ward elections.

The results of the 2009 election were as follows.[95]

Crime

During the late 1990s and first decade of the 21st century, Springfield experienced a wave of violent crime that negatively impacted the city's reputation, both regionally and nationally. At one point in the first decade of the 21st century, Springfield ranked as high as 18th in the United States' annual "City Crime Rankings." Since approximately 2006, the City of Springfield has experienced a dramatic, (nearly 50%) drop-off in citywide crime. In 2010, Springfield ranked 35th in the United States' City Crime Rankings – its 2nd lowest ranking in recent years, (in 2009, it ranked 51st). Springfield's current crime rating of 142 is down approximately 50% from its heights in the late 1990s and first decade of the 21st century.[96]

The cities of Hartford, Connecticut and New Haven, Connecticut, both of which in 2007 were cited as "resurgent" cities that Springfield should seek to emulate by the Federal Reserve Bank of Boston, are now by nearly all statistical measures, significantly more dangerous than Springfield.[97] (New Haven currently ranks 18th in the annual U.S. City Crime Rankings, and Hartford ranks 19th).[96] The Urban Land Institute states that currently "the perception of crime [in Springfield] appears to be worse than the reality."[98]

Education

Grade schools

Public schools (K–12)

Springfield has the second largest school district in Massachusetts and in New England. It operates 38 elementary schools, six high schools, six middle schools (6–8) and seven specialized schools. The main high schools in the city include the High School of Commerce, Springfield Central High School, Roger L Putnam Vocational-Technical High School, and the Springfield High School of Science and Technology, better known as Sci-Tech. There are also two charter secondary schools in the City of Springfield: SABIS International, which ranks among the top 5% of high schools nationally in academic quality, and the Hampden Charter School of Science. The city's School Committee passed a new neighborhood school program to improve schools and reduce the growing busing costs associated with the current plan. The plan faces stiff opposition from parents and minority groups who claim that the schools are still unequal. The city is required under a 1970s court order to balance schools racially, which had necessitated busing. However, since then, the city and the school's population has shifted and many of the neighborhoods are more integrated, calling into question the need for busing at all. Though the plan is likely to be challenged in court, the state Board of Education decided it did not have authority to review it, sidestepping the volatile issue while effectively condoning it.

Private schools

The Roman Catholic Diocese of Springfield operated five Catholic elementary schools in the city, all of which were consolidated into a single entity, St. Michael's Academy, in the autumn of 2009.[99] The non-denominational Pioneer Valley Christian School is located in the suburban Sixteen Acres neighborhood, educating K–12. Non-sectarian elementary schools within the City of Springfield include the Pioneer Valley Montessori School in Springfield's Sixteen Acres neighborhood and Orchard Children's Corner in suburban Indian Orchard, a Pre-Kindergarten, among others.

The Diocese runs Cathedral High School, which is the largest Catholic high school in Western Massachusetts. A non-denominational Christian school, the Pioneer Valley Christian School, is located in the suburban Sixteen Acres neighborhood of the city.[100] Two nonsectarian private schools are also located in Springfield: Commonwealth Academy[101] located on the former campus of the MacDuffie School (which moved to Granby, Massachusetts in 2011 after 130 years in Springfield), and teaches grades four through twelve, soon to enroll students in grades K-12; and the Academy Hill School,[102] which teaches kindergarten through grade eight.

Within 15 miles (24 km) of Springfield are many private prep schools, which can serve as day schools for Springfield students; they include the Williston Northampton School in Easthampton, Massachusetts; Wilbraham & Monson Academy in Wilbraham, Massachusetts; and Suffield Academy in Suffield, Connecticut.

Higher education

Universities and colleges

The Knowledge Corridor boasts the second-largest concentration of higher learning institutions in the United States, with 32 universities and liberal arts colleges and over 160,000 university students in Greater Hartford-Springfield. Within 16 miles (26 km) of Springfield's Metro Center, there are 18 universities and liberal arts colleges, which enroll approximately 100,000 students.[103]

Within the City of Springfield itself are three well-regarded private colleges and universities: Springfield College, Western New England University, and American International College—in addition to the public University of Massachusetts Amherst's urban planning program, and Springfield Technical Community College, Massachusetts' only community college dedicated to technology.

As of 2015, Springfield attracts over 20,000 university students per year. Its universities and colleges include Western New England University, famous for its law and pharmacy programs; Springfield College, famous as the birthplace of the sport of basketball (1891) and the nation's first physical education class, (1912), which specializes in sports and sports medicine; American International College, founded to educate America's immigrant population, is notable as the inventor of the Model Congress program; UMass Amherst relocated its urban design center graduate program to Court Square in Metro Center, and has indicated that a larger commitment (probably in the soon-to-be renovated former hotel building on Court Square) is possible within the next year.[104] Also, Cambridge College Springfield Regional Center, an institution that caters to working adults, is located in Springfield.

Several of Greater Springfield's institutions rank among the most prestigious and well-financed in the world. For example, Amherst College, 15 miles (24 km) north of Springfield, and Smith College, 13 miles (21 km) north of Springfield, consistently rank among America's top 10 liberal arts colleges. Mount Holyoke College – the United States' first women's college – consistently ranks among America's Top 15 colleges, and it is located only 9 miles (14 km) north of Springfield. Hampshire College, the creative and free-thinking university that has produced luminaries such as the documentarian Ken Burns and critically renowned author and mountain climber Jon Krakauer, is located only 14 miles (23 km) north of Springfield. The 30,000-student University of Massachusetts Amherst is located 16 miles (26 km) north of Springfield. Approximately 10 miles (16 km) west of Springfield, across the Memorial Bridge in Westfield, is Westfield State University, founded by noted education reformer Horace Mann. Westfield was the first university in America to admit students without regard to sex, race, or economic status.[105] Its current enrollment is approximately 6,000 students.

Just outside Springfield's northern city limits is Elms College, a fine Catholic university that for many years educated only women. Now Elms College is co-educational. Likewise, just 2 miles (3.2 km) below Springfield's southern city limit in Longmeadow is the park-like campus of Bay Path College, which once also admitted only women. Within the past decade, Bay Path has eased its restriction and started to admit men to certain programs.

Community colleges

In 1968, following the Pentagon's controversial closing of the Springfield Armory, Springfielders founded Springfield Technical Community College on 35 acres (14.2 ha) behind the Springfield Armory National Park. Springfield Technical Community College is the only "technical" community college in Massachusetts, and was founded to continue Springfield's tradition of technical innovation.[106]

Holyoke Community College, 8 miles (13 km) north of Springfield, is Greater Springfield's more traditional community college.

Library

Efforts to establish the Springfield Public Library began in the 1850s.[107][108] In fiscal year 2008, the city of Springfield spent 1.13% ($5,321,151) of its budget on its public library – some $35 per person.[109] In fiscal year 2009, Springfield spent about 1% ($5,077,158) of its budget on the library – some $32 per person.[110] Springfield has Massachusetts' 2nd largest library circulation, behind Boston.

As of 2012, the public library purchases access for its patrons to databases owned by the following companies:[111]

- EBSCO Industries

- Foundation Center

- Gale, of Cengage Learning

- Infobase Publishing

- LearningExpress, LLC

- Merriam-Webster, Inc.

- NewsBank, Inc.

- Oxford University Press

- ProQuest (products include Massachusetts Newsstand)

Media

Newspapers

Springfield's largest local newspaper is The Republican. The Republican used to be the Springfield Union-News & Sunday Republican. Smaller papers such as The Reminder and the Valley Advocate also serve Greater Springfield.