Rocky Mountain National Park

| Rocky Mountain National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

View from Bear Lake in Rocky Mountain National Park | |

| |

| Location | Larimer / Grand / Boulder counties, Colorado, United States |

| Nearest city | Estes Park and Grand Lake, Colorado |

| Coordinates | 40°20′00″N 105°42′32″W / 40.33333°N 105.70889°WCoordinates: 40°20′00″N 105°42′32″W / 40.33333°N 105.70889°W |

| Area | 265,461 acres (414.783 sq mi; 107,428 ha; 1,074.28 km2)[1] |

| Established | January 26, 1915[2] |

| Visitors | 4,155,916 (in 2015)[3] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Rocky Mountain National Park |

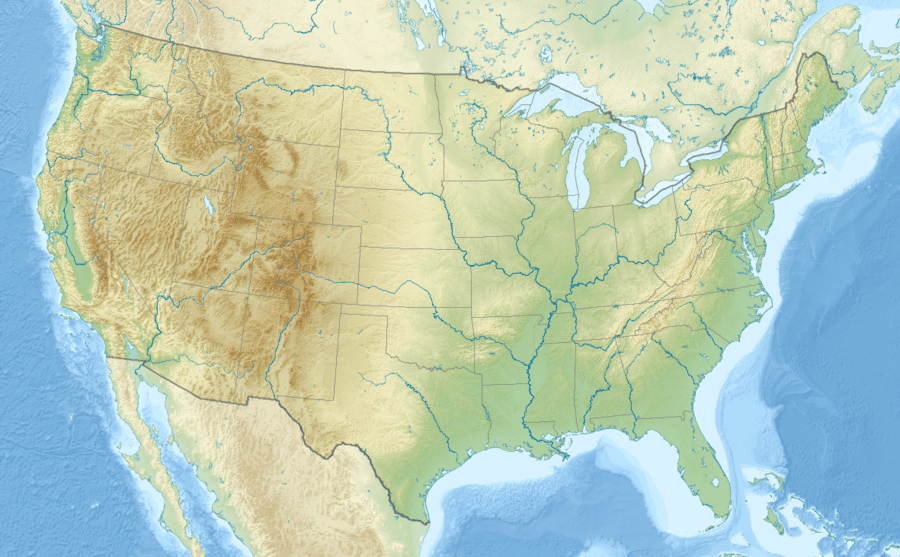

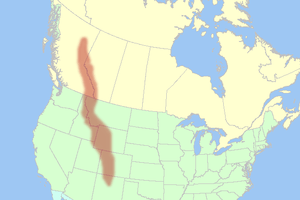

Rocky Mountain National Park is a United States national park located approximately 76 mi (122 km) northwest of Denver International Airport[4] in north-central Colorado, within the Front Range of the Rocky Mountains. The park is situated between the towns of Estes Park to the east and Grand Lake to the west. The eastern and westerns slopes of the Continental Divide run directly through the center of the park with the headwaters of the Colorado River located in the park's northwestern region.[5] The main features of the park include mountains, alpine lakes and a wide variety of wildlife within various climates and environments, from wooded forests to mountain tundra.

The Rocky Mountain National Park Act was signed by then–President Woodrow Wilson on January 26, 1915, establishing the park boundaries and protecting the area for future generations.[2] The Civilian Conservation Corps built the main automobile route, named Trail Ridge Road, in the 1930s.[2] In 1976, UNESCO designated the park as one of the first World Biosphere Reserves.[6] In 2015, more than four million recreational visitors entered the park, which is an increase of twenty one percent from the prior year.[7]

The park has a total of five visitor centers[8] with park headquarters located at the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center—a National Historic Landmark designed by the Frank Lloyd Wright School of Architecture at Taliesin West.[9] National Forest lands surround the park including Roosevelt National Forest to the north and east, Routt National Forest to the north and west, and Arapaho National Forest to the west and south, with the Indian Peaks Wilderness area located directly south of the park.[5]

Geology

Precambrian metamorphic rock formed the core of the North American continent during the Precambrian eon 4.5–1 billion years ago. During the Paleozoic era, western North America lay underneath a shallow sea, with many kilometers of limestone and dolomite deposits.[10] Precambrian Pikes Peak Granite formed during Paleozoic era and the Precambrian eon, about 300 million–1 billion years ago, when mass quantities of molten rock flowed, amalgamated, and formed the continents. At about 500 – 300 million years ago, the region began to sink and lime and mud sediments deposited in the newly formed space. Eroded granite produced sand particles that formed strata, layers of sediment, in the sinking basin.[11]

At about 300 million years ago the land lifted, creating the ancestral Rocky Mountains.[11] Fountain Formation was formed during the Pennsylvanian period of the Paleozoic era, 290–296 million years ago. Over the next 150 million years, the mountains uplifted, continued to erode, and covered themselves in their own sediment. Wind, gravity, rainwater, snow, and rivers of melted ice carved through the granite mountains over time.[12] The Ancestral Rockies were buried.[13]

Pierre Shale was formed during the Paleogene and Cretaceous periods about 70 million years ago. The region was covered a deep sea, the Cretaceous Western Interior Seaway, which deposited mass amounts of shale over the area known as the Pierre Shale. Both the thick section of shale and the marine life fossils (ammonites and skeletons of fish and such marine reptiles as mosasaurs, plesiosaurs, and extinct species of sea turtles, along with rare dinosaur and bird remains) were made. Colorado eventually drained from being at the bottom of an ocean to land again, giving yield to another fossiliferous rock layer, the Denver Formation.[14]

At about 68 million years ago, the Front Range began to rise again due to the Laramide Orogeny in the west.[14][15] During the Cenozoic Era, block uplift formed the present Rocky Mountains. The geologic make-up of Rocky Mountain National Park was also affected by deformation and erosion during that Era. The uplift disrupted the older drainage patterns and created the modern drainage patterns of today.[16]

Glaciation

Glacial geology in Rocky Mountain National Park can be seen from the tops of the peaks to the bottom of the valleys. Ice is a powerful sculptor of this natural environment and large masses of moving ice are the most powerful tools. Telltale marks of giant glaciers can be seen all throughout the park. Streams and glaciations during the Quaternary age cut through the older sediment, creating mesa tops and alluvial plains, and revealing the present Rocky Mountains.[17] The glaciation removed as much as 5,000 feet (1,500 m) of sedimentary rocks from earlier inland seas deposits. This erosion exposed the basement rock of the Ancestral Rockies. Evidence of the uplifting and erosion can be found on the way to Rocky Mountain National Park in the hogbacks of the Front Range foothills.[16] Many sedimentary rocks from the Paleozoic and Mesozoic eras exist in the basins surrounding the park.[18]

While the glaciation periods are largely in the past, Rocky still has several small glaciers.[19] The glaciers include Andrews, Sprague, Tyndall, Taylor, Rowe, Mills, and Moomaw Glaciers.[20]

Geography

Rocky Mountain National Park encompasses 265,461 acres (414.78 sq mi; 1,074.28 km2) of federal land. Wildlife and trails traverse an additional 253,059 acres (395.40 sq mi; 1,024.09 km2) of adjacent National Forest Service wilderness.[21] The Continental Divide runs through the park.[22] Rivers and streams flow from the mountains on the western side into the Pacific Basin and on the east side of the divide to the Atlantic Basin.[23]

The headwaters of the Colorado River are in Rocky Mountain National Park.[22] It has 450 miles (720 km) of streams, 350 miles (563 km) of trails, and 147[24] or 150 lakes.[22]

Rocky Mountain National Park is one of the highest national parks in the nation, with elevations from 7,860 to 14,259 feet (2,396 to 4,346 m),[25] the highest point of which is Longs Peak. Surveys show that before 2002 the peak was 14,255 feet (4,345 m) high.[26] Sixty mountain peaks over 12,000 feet (3,700 m) high provide scenic vistas.[25] On the north side of the park, the Mummy Range contains a number of smaller thirteener peaks, including Hagues Peak, Mummy Mountain, Fairchild Mountain, Ypsilon Mountain, and Mount Chiquita.[27] Several small glaciers and permanent snowfields are found in the high mountain cirques.[20]

Ecosystems

Colorado has one of the most diverse plant and animal environments of the United States, partially born from the dramatic temperature differences due to varying elevation levels and topography. In dry climates, the average temperature drops 5.4 degrees Fahrenheit with every 1,000 foot increase in elevation (9.8 degrees Celsius per 1,000 meters). Most of the state is semi-arid; the mountains receive the most precipitation in Colorado.[28]

The Continental Divide runs north to south through the park, and marks a climatic division. Ancient glaciers carved the topography into a range of ecological zones.[25] The east side of the Divide tends to be drier, with heavily glaciated peaks and cirques. The west side of the park is wetter and more lush, deep forests.[29]

There are three distinct ecosystems in the Rocky Mountain National Park, montane, subalpine, and alpine tundra. A fourth, the riparian zone, occurs throughout each of the three distinct zones. An ecosystem is defined by the National Park Service as an interaction of biologic communities with the surrounding physical environment. Each ecosystem is composed of organisms interacting with one other and with the natural, surrounding environment. Living organisms (biotic), the dead organic matter produced by them, the abiotic (non-living) environment that impacts the biotic life (water, weather, rocks, landscape) make up the members of an ecosystem.[30]

The park is designated a World Biosphere Reserve to protect its natural resources. It was the 21st of such areas on Earth identified as a protected area by the United Nations.[31] It received its designation in 1976 and its biodiversity includes afforestation and reforestation, ecology, inland bodies of water, and mammals. Its ecosystems are managed for nature conservation, environmental education and public recreation purposes. The areas of research and monitoring include: ungulate ecology and management, high-altitude revegetation, global change, acid precipitation effects, and aquatic ecology and management.[32]

Montane

The montane ecosystem is at the lowest elevations in the park, between 5,600 to 9,500 feet (1,700 to 2,900 m), where the slopes and large meadow valleys support the widest range of plant and animal life,[33][34] including montane forests, grasslands, and shrublands. The area has meandering rivers[34] and during the summer, wildflowers grow in the open meadows. Ponderosa pine trees, grass, shrubs and herbs live on dry, south-facing slopes. North-facing slopes retain moisture better than those that face south. The soil better supports dense populations of trees, like Douglas fir, lodgepole pine, and ponderosa pine. There are also occasional Engelmann spruce and blue spruce trees. Aspens thrive in high-moisture montane soils. Along streams or the shores of lakes, other water-loving small trees like willows, mountain alder, and water birch may be found. Water-logged soil in flat Montane valleys may be unable to support growth of evergreen forests.[34] The following areas are part of the montane ecosystem, Moraine Park, Horseshoe Park, Kawuneeche Valley, and Upper Beaver Meadows.[34]

Residential mammals that inhabit this park include snowshoe hares, coyotes, cougars, beavers, mule deer, moose, bighorn sheep, black bears, and Rocky Mountain elk.[34][35][36] During the fall, visitors often flock to the park to witness the elk rut.[37]

Subalpine

Above 9,000 feet (2,700 m), the montane forests give way to the subalpine forest.[33] Subalpine fir and Engelmann spruce forests covers the mountainsides in subalpine areas. They grow straight and tall in the lower subalpine forests, become shorter and deformed nearer treeline.[35] At treeline, tree seedlings may germinate on the lee side of rocks and grow only as high as the rock provides wind protection. Further growth is more horizontal than vertical. The low growth of dense trees is called krummholz, which may become well-established and live for several hundred to a thousand years old.[35]

In the subalpine, Lodgepole pines and huckleberry have established themselves in previous burn areas. Hidden among the trees are crystal clear lakes and fields of wildflowers. There are a number of shrubs and plants. Fauna is also somewhat diverse, with elk, deer, mountain lions, chipmunks and other animals. Black bears usually hang out in subalpine forests to eat berries and seeds. Clark's nutcracker is one of the many birds found in the area. The subalpine ecosystem occupies elevations just below tree-line between 9,000 and 11,000 feet.[35] Sprague Lake and Odessa Lake are two places in the subalpine zone.[35]

Alpine tundra

Above tree line, at approximately 11,000 feet (3,400 m), trees disappear and the vast alpine tundra takes over.[33] Over one third of the park resides above tree line This is due to the cold climate and strong winds. Few plants grow there. Those that do are mostly perennials and although many are dwarfed their few blossoms may be full-sized.[36]

Cushion plants have long taproots that extend deep into the rocky soil. Their diminutive size, like clumps of moss, limits the effect of harsh winds. Many flowering plants of the tundra have dense hairs on stems and leaves to provide wind protection or red-colored pigments capable of converting the sun's light rays into heat. Some plants take two or more years to form flower buds, which survive the winter below the surface and then open and produce fruit with seeds in the few weeks of summer. Grasses and sedges are common where tundra soil is well-developed.[36]

Non-flowering lichens cling to rocks and soil. Their enclosed algal cells can photosynthesize at any temperature above 32 degrees Fahrenheit, and the outer fungal layers can absorb more than their own weight in water. Adaptations for survival amidst drying winds and cold temperatures may make tundra vegetation seem very hardy, but in some respects it remains very fragile. Footsteps can destroy tundra plants and it may take hundreds of years to recover.[36] Animals that live in the alpine tundra include yellow-bellied marmots, pikas, white-tailed ptarmigans, and elk, who graze on the vegetation. Plants found there include alpine sunflowers, and alpine forget-me-not flowers.[36]

Riparian

The riparian ecosystem runs through the montane, subalpine, and alpine tundra zones and creates a foundation for life especially for species that thrive next to streams, rivers, and lakes.[38] The headwaters of the Colorado River, which provides water to many states, are located on the west side of the park. On the east side are the Fall River, Cache le Poudre and Big Thompson Rivers. Just like the other ecosystems in the park, the riparian is affected by the climatic variables of temperature and precipitation, and elevation. Generally riparian areas in valleys will have cooler temperatures than communities on slopes and ridge tops. Depending on elevation there is more or less precipitation, and this creates a shift in the types of plants and animals found there.[39]

Climate

The complex interactions of elevation, slope, exposure and regional-scale air masses affect the climate within the park,[40][41] which is noted for its extreme weather patterns.[41] A "collision of air masses" from several directions produces some of the key weather events that affect the park. When cold arctic air meets moist air from the Gulf of Mexico at the Front Range, " intense, very wet snowfalls with total snow depth measured in the feet" is deposited at the park.[40]

Elevation

High-elevation areas within the park receive twice as much precipitation, generally in the form of deep winter snowfall, than the lower areas.[40] Arctic conditions are prevalent during the winter, with sudden blizzards, high winds, and deep snowpack. High country overnight trips require gear suitable for -35 °F or below.[41]

The subalpine region does not begin to experience spring-like conditions until June. Wildflowers bloom from late June to early August.[41]

Below 9,400 feet (2,900 m), temperatures are often moderate, although nighttime temperatures are cool, as is typical of mountain weather.[41] Spring comes to the montane area by early May, when wildflowers begin to bloom. Weather may become subject to unpredictable changes in temperature and precipitation. There may be snow on trails through May.[41] In July and August, temperatures are generally in the 70s or 80s °F during the day, and as low as the 40s °F at night.[41] Lower elevations receive most of their precipitation in the form of summer rain.[40]

In general, there may be sudden changes in the weather during the summer, with as much as 20 °F drops in temperature, windy conditions, and afternoon thunderstorms.[41] The extreme weather is often the result of convectional storms.[40]

Continental Divide

The park's climate is also affected by the Continental Divide, which runs northwest to southeast through the center of the park and atop the high peaks. This accounts for two distinct climate patterns - one typical of the east side near Estes Park and the other associated with the Grand Lake area on the park's west side.[41] The west side of the park experiences more snow, less wind, and clear cold days during the winter months.[41]

Climate change study

The Rocky Mountain National Park and a national park in the Appalachian Mountains were selected to participate in a climate change study that began in Fall 2011 by a group of members of the academic scientific community, National Park Service, and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA). The team's objective is to "develop and apply decision support tools that use NASA and other data and models to assess vulnerability of ecosystems and species to climate and land use change and evaluate management options."[42]

Over the past century there has been an increase in the average low temperature of 3.4 °F.[43][lower-alpha 1] The high temperatures have also been increasing, but at a slower rate. As a result of the temperature changes, snow is melting from the mountains earlier. This makes for drier summers and is probably leading to an earlier, longer fire season.[40] Mountain pine beetles have reproduced more rapidly, and they do not die off in the winters at the previous rate, since park has experienced higher temperatures since the 1990s. Consequently, this has led to an increased rate of tree mortality in the park.[44]

The climate change study projects temperature increases, with greater warming in the summer and higher extreme temperatures by 2050. Due to the increased temperature, there is a projected moderate increase in the rate of water evaporation. Reduced snowfall—perhaps 15% to 30% less than current amounts of snow, elimination of surface hail, and higher likelihood of intense precipitation events are predicted by 2050. Droughts may be more likely due to increased temperatures, increased evaporation rates, and potential changes in precipitation.[44]

Park regions

There are five regions, or geographical zones, within the park.

1 - Moose and big meadows

Region 1 is known for moose and big meadows and is located on the west, or Grand Lake, side of the Continental Divide.[45] Thirty miles of the Continental Divide National Scenic Trail loop through the park and pass through alpine tundra and scenery.[46] A geographical anomaly is found along the slopes of the Never Summer Mountains, where the Continental Divide forms a horseshoe–shaped bend for about 6 miles (9.7 km) from north to south and then west out of the park.[47][5] The sharp bend results in streams on the eastern slopes of the range joining the headwaters of the Colorado River that flow south and west, eventually reaching the Pacific Ocean via the Gulf of California.[5][48] Meanwhile, streams on the western slopes join rivers that flow north and then east and south eventually reaching the Atlantic Ocean via the Gulf of Mexico.[5][48] Baker Pass crosses the Continental Divide through the Never Summer Mountains and into the Michigan River drainage to the west of Mount Nimbus[46]—a drainage that feeds streams and rivers that drain into the Gulf of Mexico.[48]

Other mountain passes are La Poudre Pass and Thunder Pass, which was once used by stage coaches and is a route to Michigan Lakes. Little Yellowstone has unique geological features like the Grand Canyon of Yellowstone. The Green Mountain trail once was a wagon road used to haul hay from Big Meadows. Flattop Mountain, which can be accessed by the eastern and western sides of the park, is near Green Mountain. Shadow Mountain Fire Lookout is on the National Register of Historic Places.[46] Paradise Park is an essentially hidden and protected wild area with no maintained trails penetrating it.[49]

Big Meadows contains grasses and wildflowers is reached via Onahu, Tonahutu, and Green Mountain trails. Another scenic area is Long Meadows. Kawuneeche Valley, or Coyote Valley, of Upper Colorado River is a good place to birdwatching, shoe-shoeing, and cross-country skiing. The valley trail loops through Kawuneeche.[46] There were 39 known mines in Kawuneeche Valley, but less than 20 of those have archived records and archeological remains.[50] The old gold mining town of the 1880s, LuLu City is in this region. Little is left of the town, that is often visited by moose.[46] There are many trails, some named for the sites in this region. A few of the trails are Tonahutu Creek Trail and Onahu Creek Loop.[46]

Skeleton Gulch, Cascade Falls, North Inlet Falls, Granite Falls, and Adams Falls are found in the west side of the park. The lakes there include Bowen Lake, Lake Verna, Lake of the Clouds, Haynach Lakes, Timber Lake, and Lone Pine Lake. Others are Lake Nanita and Lake Nokoni.[46]

2 - Alpine region

Region 2 is the Alpine region of the park with accessible tundra trails at high elevation; known for spectacular vistas.[45] Within the region are Mount Ida, with tundra slopes and an "expansive view of the Divide", and Specimen Mountain, which has a high steep trail and opportunity to view bighorn sheep and marmots. Forest Canyon Pass is near the top of the Old Ute Trail that once linked villages across the Continental Divide.[51]

Chapin Pass trail traverses a dense forest to beautiful views of the Chapin Creek valley and on above timberline to the western flank of Mount Chapin. Tundra Communities Trail, accessible from Trail Ridge Road, is a hike offers a view of the tundra and its wildflowers. Other trails are Tombstone Ridge and Ute Trail, which starts at the tundra and is mostly downhill from Ute Crossing to Upper Beaver Meadows; it has one backcountry site. Cache La Poudre River trail begins north of Poudre Lake on the west side of the valley near Milner Pass and heads downwards towards the Mummy Pass trail junction. Lake Irene is a recreation and picnic area. [51]

3 - Wilderness

Region 3, known for wilderness escape, is in the northern part of the Park and is accessed from the Estes Park area.[45]

The Mummy Range is a short mountain range in the north of the park. The Mummies tend to be gentler and more forested than the other peaks in the park, though some slopes are rugged and heavily glaciated, particularly around Ypsilon Mountain and Mummy Mountain. Bridal Veil Falls is a scenic point and trail accessible from the Cow Creek trailhead, at the Continental Divide Research Center.[52] West Creek Falls and Chasm Falls, near Old Fall River Road, are also in this region. The Alluvial Fan trail that takes you to a bridge over the river that had been the site of the Lawn Lake Flood.[53]

Paul Bunyan's boot is the name of a balanced rock. The Balanced Rock trail leads to Gem Lake. Black Canyon Trail intersects the Cow Creek Trail, and forms part of the Gem lake loop. It goes through the old McGregor Ranch valley, past Lumpy Ridge rock formations, and a loop hike goes into the McGraw Ranch valley.[53]

Cow Creek Trail follows Cow Creek, with its many beaver ponds. It extends past the Bridal Falls turnoff as the Dark Mountain trail, then joins the Black Canyon trail to intersect the Lawn Lake trail shortly below the lake.[53] North Boundary Trail connects to the Lost Lake trail system. North Fork Trail begins outside of the park, in the Comanche Peak Wilderness before reaching the park boundary and ends at Lost Lake. Stormy Peaks Trail connects Colorado State University's Pingree Park campus in the Comanche Peak Wilderness and the North Fork Trail inside the park.[53]

Beaver Mountain Loop passes through forest and meadows, crosses Beaver Brook and several aspen-filled drainages. There is a great view of Longs Peak from the trail, that is also used by horseback riders.[53] Deer Mountain Trail gives a 360 degree view of east Rocky Mountain National Park. The summit plateau of Deer Mountain offers spectacular views of the Continental Divide. During the winter, the lower trail generally has little snow, packed and drifted snow are to be expected on the switchbacks. Snow cover on the summit may be three to five feet deep, requiring use of snowshoes or skis.[53]

The trail to Lake Estes in Estes Park meanders through a bird sanctuary, beside a golf course visited by elk, along the Big Thompson River and Fish Creek, through the lakeside picnic area and along the lakeshore. It is used by birdwatchers, bikers, and hikers.[53]

Lawn Lake Trail climbs to Lawn Lake and Crystal Lake, one of the parks deepest lakes, in the alpine ecosystem and along the course of the Roaring River. The river shows the massive damage caused by a dam failure in 1982 that claimed the lives of three campers. A strenuous snowshoe in the winter.[53] Ypsilon Lake leads to Chipmunk Lake, with views of Longs Peak, pine forests with grouseberry and bearberry bushes. It also offers views of the canyon gouged out by rampaging water that broke loose from Lawn Lake Dam in 1982. Visible is the south face of Ypsilon Mountain, with its Y shaped gash rising sharply from the shoreline.[53]

Gem Lake is high among the rounded granite domes of Lumpy Ridge. Untouched by glaciation, this outcrop of 1.8 billion-year-old granite has been sculpted by wind and chemical erosion into a backbone-like ridge. Pillars, potholes, and balanced rocks are found midway along the trail. There are views of the Estes Valley and Continental Divide.[53] Potts Puddle trail is accessible from the Black Canyon trail.[53]

4 - Heart of the park

Region 4 is the heart of the Park and known for easy access, great views, and lake hikes. It contains the most visited and famous trails and trailheads.[45] Flattop Mountain is a tundra hike and easiest hike to the Continental Divide. The hike up Hallett Peak passes through three climate zones, crosses over Flattop Mountain, traverse the ridge supporting Tyndall Glacier, and ascends to the summit of Hallett Peak.[54]

Bear Lake is a high-mountain lake in a spruce/fir forest at the base of Hallett Peak and Flattop Mountain.[54] Bierstadt Lake sits atop a lateral moraine, Bierstadt Moraine, and drains into Mill Creek. There are several trails that lead to Bierstadt Lake, along groves of aspens and lodgepole pines.[55] North of Bierstadt Moraine is Hollowell Park, a large and marshy meadow along Mill Creek. The Hollowell Park trail runs along Steep Mountain's south side. There had been ranches, lumber, and sawmill enterprises in Hollowell Park into the early 1900s.[55]

Glacial Basin was the site of a resort ran by Abner and Alberta Sprague, from whom Sprague Lake is named. The lake is a shallow body of water that was created when the Spragues dammed Boulder Brook to create a spot for fishing. It is now a good site for birdwatching, hiking, and viewing the mountain peaks. There is camping at the Glacier Basin campground.[56]

Dream Lake is the most photographed lake and noted for its winter showshoeing. Emerald Lake is near Nymph Lake and the north shore of Dream Lake. It is below the saddle between Hallett Peak and Flattop Mountain.[54] Lake Haiyaha (a Native American word for "big rocks") surround this lake's shore along with ancient twisted and picturesque pine trees in rock crevices. Nymph Lake is named for the yellow lily, Nymphaea polysepala on its lake. Lake Helene is at the head of Odessa Gorge, east of Notchtop Mountain. Two Rivers Lake is found along the hike to Odessa Lake from Bear Lake, it has one backcountry site. The Cub Lake trail passes Big Thompson River, flowery meadows, and stands of pine and aspen trees. There is Ice and deep snow during the winter, requiring the use of skis or snowshoes.[54]

The Fern Lake trail passes Arch Rock formations, The Pool, and the cascading water of Fern Falls. There are two backcountry sites near the Lake, and two closer to the trailhead. Odessa Lake has two approaches. One is along the Flattop trail from Bear Lake, and the other is from the Fern Lake trailhead, along which are Fern Creek, The Pool, Fern Falls, and Fern Lake itself along the way. There is one backcountry site.[54] Other lakes are Jewel Lake, Mills Lake, Black Lake, Blue Lake, Lake of Glass, and Spruce Lake.[54]

The Pool is a large turbulent water pocket formed below where Spruce and Fern Creeks join the Big Thompson River. The winter route is along a gravel road, which leads to a trail at the Fern Lake Trailhead. Along the route are beaver-cut aspen, frozen waterfalls on the cliffs, and the Arch Rocks.[54] Fern Falls are steep falls. The trail to Alberta Falls runs by Glacier Creek and Glacier Gorge.[54]

Wind River Trail leaves the East Portal and follows the Wind River to join with the Storm Pass trail. There are three backcountry sites.[54] Other sites in the area are The Loch, Loch Vale, Mill Creek Basic, Andrews Glacier, Sky Point, Timberline Falls, Upper Beaver Meadows, and Storm Pass.[54]

5 - Waterfalls and back country

Region 5, known for waterfalls & back country, is south of Estes Park and contains Longs Peak (RMNP's iconic 'fourteener') and the Wild Basin area.[45] Peaks and passes include Longs Peak, Lily Mountain, Estes Cone, Twin Sisters, Boulder-Grand Pass, Granite Pass[57] Eugenia Mine operated about the turn of the century, there are remains of old equipment and a log cabin.[57] Sites and trails include Boulder Field, Wild Basin Trail, Homer Rouse Memorial Trail.[57]

Enos Mills, the "father of Rocky Mountain National Park," enjoyed walking to Lily Lake from his nearby cabin. Look for wildflowers in the spring and early summer. In the winter the trail around the lake is often suitable for walking in boots, or as a short snowshoe or ski. Other lakes in the Wild Basin, many with backcountry sites, include Chasm Lake, Snowbank Lake, Lion Lakes 1 and 2, Thunder Lake, Ouzel Lake, Finch Lake, Bluebird Lake, Pear Lake, and Sandbeach Lake. Waterfalls found there are Ouzel Falls, Trio Falls, Copeland Falls, There's also Calypso Cascades.[57]

Recreational activities

The park contains a network of trails that range from easy, paved paths suitable for hiking by family members or people with disabilities to strenuous trails for experienced, conditioned hikers. There are also off-trail routes for backcountry hikes. In most cases, the trails are for summer use, at other times of the year, many may not be safe due to weather conditions.[58] There are dozens of designated backcountry camp sites. Horseback riding is permitted on most trails.[59] Llamas and other pack animals are allowed on most of the trails, too.[60]

During the winter, only the edges of the park are accessible for recreational activities, since most of Trail Ridge Road is closed due to heavy snow.[31] Winter activities, like snowshoeing and cross-country skiing, are then down from either the Estes Park or Grand Lake entrances. On the east side, there are trails off of Bear Lake Road, such as the Bear Lake, Bierstadt Lake, and Sprague Lake trails and at Hidden Valley. There are also viable snowshoeing trails on the west side of the park.[31][61] Backcountry-style Telemark skiing can be climbed to on the higher slopes, after avalanche danger is over.[62]

Rock climbing and mountaineering opportunities include Lumpy Ridge,[63] Hallett Peak, and Longs Peak, the highest peak, the easiest route is the Keyhole Route. This eight-mile (13 km) one-way climb has an elevation gain of 4,850 ft (1,480 m). The vast east face, including the area known as The Diamond, is home to many classic big wall rock climbing routes. and among others, are famous rock climbing areas. Many of the highest peaks have technical ice and rock routes on them, ranging from short scrambles to long multi-pitch climbs.

Fishing is found in the many lakes and streams in the park,[59] and camping is allowed at several designated campgrounds.[64]

Access

The park may be accessed through Estes Park or via the western entrance at Grand Lake. Trail Ridge Road, also known as U.S. 34, connects the eastern and western sides of the park.[65] The park has a total of five visitor centers. The Alpine Visitor Center is located in the tundra environment along the Trail Ridge Road, while Beaver Meadows and Fall River are both near Estes Park, with Kawuneeche in the Grand Lake area, and the Moraine Park Discovery Center near the Beaver Meadows entrance and visitor center.[8]

Trail Ridge Road and other roads

Trail Ridge Road is 48 miles (77 km) long[66] and connects the entrances in Grand Lake and Estes Park. Running from east to west, it crosses the Continental Divide.[67] Numerous short interpretive trails and pullouts along the road serve to educate the visitor on the history, geography, and ecology of the park.

The highest point of the road is 12,183 feet (3,713 m),[66] and eleven miles of the road are above the treeline at 11,500 feet (3,500 m).[66][68] Most visitors to the park drive over the famous Trail Ridge Road, but other roads include Fall River Road and Bear Lake Road.[68] The park is open every day of the year, weather permitting.[69] Due to the extended winter season in higher elevations, Trail Ridge Road between Many Parks Curve and the Colorado River Trailhead is closed much of the year. It opens by Memorial Day and closes in mid-October, generally after Columbus Day.[66] Fall River Road does not open until about July 4 and closes by, or in, October for vehicular traffic.[70] Snow may also fall in sufficient quantities in higher elevations to require temporary closure of the roads into July,[41][66] which is reported on the road status site.[68]

Estes Park

Most visitors enter the park through the eastern entrances near Estes Park, which is about 71 miles (114 km) northwest of Denver.[65] The most direct route to Trail Ridge Road is the Beaver Meadows Entrance, which is west of Estes Park on U.S. 36 is, which leads to the Beaver Meadows Visitor Center and park headquarters. North of that entrance is the Fall River entrance, which leads to Trail Ridge Road and Old Fall River Road.[65] There are three routes into Estes Park. One is U.S. Highway 34 that runs along Big Thompson Canyon from I-25. Another is U.S. 36 through Boulder and up to U.S. 34. Last is the Peak to Peak Highway, or State Highway 7.[65]

The nearest airport is Denver International Airport[65] and the closest train station is the Denver Union Station. Estes Park may be reached by rental car, shuttle or RTD bus.[65][71] During peak tourist season, there is free shuttle service within the park and the town of Estes Park provides shuttle service to Estes Park Visitor Center, surrounding campgrounds, and the Rocky Mountain National Park's shuttles.[65]

Grand Lake

Visitors may also enter at the western side of the park from U.S. 34 near Grand Lake. U.S. 34 is reached by taking U.S. 40 north from I-70.[65] The closest railroad station is the Amtrak station in Granby, which is 20 miles (32 km) from the western entrance of the park. Taxi service is available into the park.[71]

See also

- History of Rocky Mountain National Park

- Rocky Mountain National Park topics

- Southern Rocky Mountain Front, where the Rocky Mountains meet the plains

Notes

References

- ↑ "The National Parks: Index 2009-2011" (PDF). National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 "Brief Park History". nps.gov. National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved December 4, 2016.

- ↑ "NPS Annual Recreation Visits Report". National Park Service. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain National Park Mileages and Elevations". nps.gov. National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Rocky Mountain National Park Maps". nps.gov. National Park Service. n.d. Archived from the original on October 8, 2016. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Biosphere Reserve Information, United States of America, Rocky Mountain". unesco.org. UNESCO. August 17, 2000. Archived from the original on August 24, 2015. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Annual Visitation Report by Years: 2005 to 2015". National Park Service. n.d. Retrieved November 29, 2016.

- 1 2 "Rocky Mountain National Park Visitor Centers". National Park Service. n.d. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Beaver Meadows Visitor Center Review | Rocky Mountain NP | Fodor's Travel Guides". Fodors.com. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ↑ Gadd, Ben (2008). "Geology of the Rocky Mountains and Columbias" (PDF). Retrieved January 1, 2010.

- 1 2 Kirk R. Johnson; Robert G. Raynolds (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. p. 1. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- ↑ Kirk R. Johnson; Robert G. Raynolds (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. p. 6. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- ↑ Kirk R. Johnson; Robert G. Raynolds (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. p. 10. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- 1 2 Kirk R. Johnson; Robert G. Raynolds (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. p. 16. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- ↑ "Teacher Guide to RMNP Geology" (PDF). National Park Service. p. 8. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- 1 2 "Teacher Guide to RMNP Geology" (PDF). National Park Service. pp. 8–9. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ↑ Kirk R. Johnson; Robert G. Raynolds (2006). Ancient Denvers: Scenes from the Past 300 Million Years of the Colorado Front Range. Fulcrum Publishing for Denver Museum of Nature and Science. p. 30. ISBN 1-55591-554-X.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain National Park - Geologic History". National Park Service. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Glaciers". National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Glaciers". National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016. - 1 2

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Glaciers of Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Glaciers of Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016. - ↑ "National Forest Ranger Districts". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Rocky Mountain National Park". Backpacker Magazine. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ Kim Lipker (February 9, 2016). Day and Overnight Hikes: Rocky Mountain National Park. Menasha Ridge Press, Incorporated. p. PT19. ISBN 978-1-63404-016-7.

- ↑ "About Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain Hiking Trails. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Rocky Mountain National Park: Natural Features and Ecosystems". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ "No tall tale: State higher than thought". Skyrunner.com. July 7, 2002. Retrieved June 4, 2013.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Geological Survey document: "Mummy Range - Decision Card". U.S. Geological Survey - Geological Names Information System. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Geological Survey document: "Mummy Range - Decision Card". U.S. Geological Survey - Geological Names Information System. Retrieved October 28, 2016. - ↑ Fraces Alley Kelly; Carron A. Meaney (1995). Explore Colorado: A Naturalist's Notebok. Photography by John Fielder. Englewood, Colorado: Westcliff Publishers and Denver Museum of Natural History. pp. 10–13. ISBN 1-56579-124-X.

- ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress document: "Majestic view from the old, one-way, dirt Fall River Road in Rocky Mountain National Park in the Front Range of the spectacular and high Rockies in north-central Colorado". Library of Congress - Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the Library of Congress document: "Majestic view from the old, one-way, dirt Fall River Road in Rocky Mountain National Park in the Front Range of the spectacular and high Rockies in north-central Colorado". Library of Congress - Prints & Photographs Online Catalog. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Ecosystems of Rocky Teacher Guide" (PDF). Rocky Mountain National Park. p. 4. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- 1 2 3 Claire Walter (2004). Snowshoeing Colorado. Fulcrum Publishing. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-1-55591-529-2.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain National Park". UNESCO. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- 1 2 3

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Nature and Ecosystems". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Nature and Ecosystems". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016. - 1 2 3 4 5

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Montane Ecosystem". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Montane Ecosystem". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016. - 1 2 3 4 5

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Subalpine Ecosystem". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Subalpine Ecosystem". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016. - 1 2 3 4 5

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Alpine Tundra Ecosystem". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Alpine Tundra Ecosystem". National Park Service. Retrieved November 1, 2016. - ↑ "Watching Wildlife - Horseshoe Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved November 1, 2016.

- ↑ "Ecosystems of Rocky Teacher Guide" (PDF). Rocky Mountain National Park. p. 9. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Ecosystems of Rocky Teacher Guide" (PDF). Rocky Mountain National Park. p. 17. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Rocky Mountain National Park Climate Primer" (PDF). Montana State University. p. 1. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Weather". NPS. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Weather". NPS. Retrieved November 2, 2016. - ↑ "Landscape Climate Change Vulnerability Project". Montana State University. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- 1 2

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Climate Change". National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Climate Change". National Park Service. Retrieved November 3, 2016. - 1 2 "Rocky Mountain National Park Climate Primer" (PDF). Montana State University. p. 3. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park Trails and Trailheads by Region". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park Trails and Trailheads by Region". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved October 30, 2016. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Hiking trails on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved October 30, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Hiking trails on the west side of Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved October 30, 2016. - ↑ "Where Locals Hike in Rocky Mountain National Park". My Rocky Mountain Park. National Park Trips Media. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline data. The National Map, accessed December 4, 2016

- ↑ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 284. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- ↑ "Rocky Mountain National Park History - Mining" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- 1 2 "Alpine Trails". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- ↑ Brachfeld, Aaron (September 2015). "Trail to Bridal Veil Falls, Rocky Mountain National Park". the Meadowlark Herald (September 2015). the Meadowlark Herald. Retrieved 2015-09-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 "Hiking trails on the north side of Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved November 6, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "Trails in the Heart of the Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- 1 2 Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 35. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- ↑ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 33. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- 1 2 3 4 "Trails in the Wild Basin and Longs Peak of the Rocky Mountain National Park". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved November 7, 2016.

- ↑ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- 1 2 Lisa Gollin-Evans (3 June 2011). Outdoor Family Guide to Rocky Mountain National Park, 3rd Edition. The Mountaineers Books. p. 62. ISBN 978-1-59485-499-6.

- ↑ "Horse and Pack Animals - Rocky Mountain National Park" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved November 10, 2016.

- ↑ Andy Lightbody; Kathy Mattoon (3 December 2013). Winter TrailsTM Colorado: The Best Cross-Country Ski and Snowshoe Trails. Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 26–32. ISBN 978-1-4930-0716-5.

- ↑ Alan Apt; Kay Turnbaugh (7 July 2015). Afoot and Afield: Denver, Boulder, Fort Collins, and Rocky Mountain National Park: 184 Spectacular Outings in the Colorado Rockies. Wilderness Press. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-89997-755-3.

- ↑ Lisa Gollin-Evans (3 June 2011). Outdoor Family Guide to Rocky Mountain National Park, 3rd Edition. The Mountaineers Books. pp. 63–64. ISBN 978-1-59485-499-6.

- ↑ Best of Rocky Mountain National Park Hiking Trails. Adler Publishing. 1998. p. 1. ISBN 978-0-930657-39-0.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Rocky Mountain National Park - Getting There". Frommers. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Trail Ridge Road". Rocky Mountain National Park. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

- ↑ Lisa Foster (2005). Rocky Mountain National Park: The Complete Hiking Guide. Big Earth Publishing. p. 115. ISBN 978-1-56579-550-1.

- 1 2 3

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Road Status". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Road Status". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016. - ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Getting Around". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Getting Around". National Park Service. Retrieved October 28, 2016. - ↑

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Old Fall River Road". National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016.

This article incorporates public domain material from the National Park Service document: "Rocky Mountain National Park - Old Fall River Road". National Park Service. Retrieved November 2, 2016. - 1 2 "Ride a Train, Bus or Taxi to Rocky Mountain National Park". National Park Trips Media. Retrieved October 28, 2016.

Further reading

- Andrews, Thomas G. (2015). Coyote Valley: Deep History in the High Rockies. Harvard University Press. ISBN 0674088573.

- Buchholtz, C. W. (1983). Rocky Mountain National Park: A History. University Press of Colorado. ISBN 0-87081-146-0.

- Cole, James C.; Braddock, William A. (2009). Geologic Map of the Estes Park 30' x 60' Quadrangle, North-Central Colorado. Scientific Investigations Map 3039. U.S. Geological Survey. ISBN 978-1-4113-2221-9. This source discusses the geology of the quadrangle, which covers most of Rocky Mountain National Park.

- Emerick, John C. (1995). Rocky Mountain National Park Natural History Handbook. Roberts Hinehart Publishers/Rocky Mountain Nature Association. ISBN 1-879373-80-7.

- Frank, Jerry J. Making Rocky Mountain National Park: The Environmental History of an American Treasure (2013)

- Mills, Enos and John Fielder. Rocky Mountain National Park: A 100 Year Perspective (1995)

- Musselman, Lloyd K. (July 1971). Rocky Mountain National Park: Administrative History, 1915-1965 (Online ed.). Washington, D.C.: U.S. Dept. of the Interior, National Park Service, Office of History and Historic Architecture, Eastern Service Center. Retrieved 18 November 2014.

- U.S. Dept. of the Interior. Rocky Mountain [Colorado] National Park (2011) online free

External links

- Rocky Mountain National Park (National Park Service)

- Rocky Mountain National Park map

- Rocky Mountain Conservancy

- Virtual ride over Trail Ridge Road