Canyonlands National Park

| Canyonlands National Park | |

|---|---|

|

IUCN category II (national park) | |

|

Looking over the Green River from Island in the Sky | |

| |

| Location | San Juan, Wayne, Garfield, and Grand counties, Utah, United States |

| Nearest city | Moab, Utah |

| Coordinates | 38°10′01″N 109°45′35″W / 38.16691°N 109.75966°WCoordinates: 38°10′01″N 109°45′35″W / 38.16691°N 109.75966°W |

| Area | 337,598 acres (527.497 sq mi; 136,621 ha; 1,366.21 km2)[1] |

| Established | September 12, 1964 |

| Visitors | 634,607 (in 2015)[2] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | Canyonlands National Park |

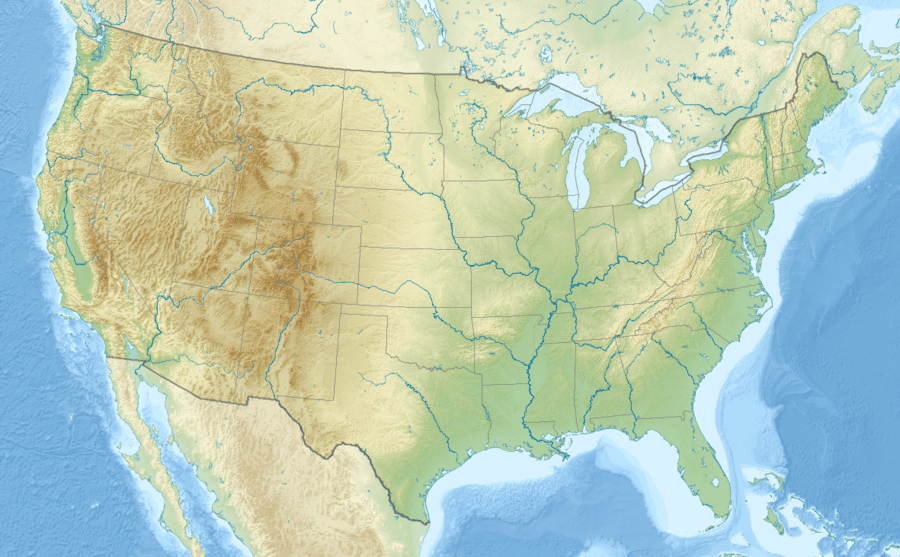

Canyonlands National Park is a U.S. National Park located in southeastern Utah near the town of Moab. It preserves a colorful landscape eroded into countless canyons, mesas, and buttes by the Colorado River, the Green River, and their respective tributaries. Legislation creating the park was signed into law by President Lyndon Johnson on September 12, 1964.[3]

The park is divided into four districts: the Island in the Sky, the Needles, the Maze, and the combined rivers—the Green and Colorado—which carved two large canyons into the Colorado Plateau. While these areas share a primitive desert atmosphere, each retains its own character.[4] Author Edward Abbey, a frequent visitor, described the Canyonlands as "the most weird, wonderful, magical place on earth—there is nothing else like it anywhere."[5]

Recreation

Canyonlands is a popular recreational destination. Since 2007, more than 400,000 people have visited the park each year with a record of 634,607 visitors in 2015.[2] The geography of the park is well suited to a number of different recreational uses. Hikers, mountain bikers, backpackers, and four-wheelers all enjoy traveling the rugged, remote trails within the Park. The White Rim Road traverses the White Rim Sandstone level of the park between the rivers and the Island in the Sky. Since 2015, day-use permits must be obtained before travelling on the White Rim Road due to the increasing popularity of driving and bicycling along it. The park service's intent is to provide a better wilderness experience for all visitors while minimizing impacts on the natural surroundings.[6][7]

Rafters and kayakers float the calm stretches of the Green River and Colorado River above the Confluence. Below the Confluence, Cataract Canyon contains powerful whitewater rapids, similar to those found in the Grand Canyon. However, since there is no large impoundment on the Colorado River above Canyonlands National Park, river flow through the Confluence is determined by snowmelt, not management. As a result, and in combination with Cataract Canyon's unique graben geology, this stretch of river offers the largest whitewater in North America in heavy snow years.

The Island in the Sky district, with its proximity to the Moab, Utah area, attracts the majority (59 percent) of park users. The Needles district is the second most visited, drawing 35 percent of visitors. The rivers within the park and the remote Maze district each only account for 3 percent of park visitation.[8]

Political compromise at the time of the park's creation limited the protected area to an arbitrary portion of the Canyonlands basin. Conservationists hope to complete the park by bringing the boundaries up to the high sandstone rims that form the natural border of the Canyonlands landscape.[9]

Geography

The Colorado River and Green River combine within the park dividing it into three districts called the Island in the Sky, the Needles and the Maze. The Colorado River flows through Cataract Canyon below its confluence with the Green River.

The Island in the Sky district is a broad and level mesa to the north of the park between Colorado and Green river with many overlooks from the White Rim, a sandstone bench 1,200 feet (366 m) below the Island, and the rivers, which are another 1,000 feet (305 m) below the White Rim.

The Needles district is located east of the Colorado River and is named after the red and white banded rock pinnacles which dominate it, but various other forms of naturally sculptured rock such as canyons, grabens, potholes, and a number of arches similar to the ones of the nearby Arches National Park can be found as well. Unlike Arches National Park, where many arches are accessible by short to moderate hikes or even by car, most of the arches in the Needles district lie in back country canyons and require long hikes or four-wheel-drive trips to reach them.

The area was once home of the Ancestral Puebloans, of which many traces can be found. Although the items and tools they used have been largely taken away by looters, some of their stone and mud dwellings are well-preserved.[10] The Ancestral Puebloans also left traces in the form of petroglyphs, most notably on the so-called Newspaper Rock near the Visitor Center at the entrance of this district.

The Maze district is located west of the Colorado and Green rivers, and is the least accessible section of the park, and one of the most remote and inaccessible areas of the United States.[11][12]

A geographically detached section of the park located west-northwest of the main unit, Horseshoe Canyon Unit, contains panels of rock art made by hunter-gatherers from the Late Archaic Period (2000-1000 BC) pre-dating the Ancestral Puebloans.[13][14][15] Originally called Barrier Canyon, Horseshoe's artifacts, dwellings, pictographs, and murals are some of the oldest in America.[14] It is believed that the images depicting horses date from after 1540 AD, after the Spanish re-introduced horses to America.[14]

Wildlife

Mammals that roam this park include black bears, coyotes, skunks, bats, elk, foxes, bobcats, badgers, two species of ring-tailed cats, pronghorns, and cougars.[16] Desert cottontails, kangaroo rats and mule deer are commonly seen by visitors.[17]

At least 273 species of birds inhabit the park.[18] A variety of hawks and eagles are found, including the Cooper's hawk, the northern goshawk, the sharp-shinned hawk, the red-tailed hawk, the golden and bald eagles, the rough-legged hawk, the Swainson's hawk, and the northern harrier.[19] Several species of owls are found, including the great horned owl, the northern saw-whet owl, the western screech owl, and the Mexican spotted owl.[19] Grebes, woodpeckers, ravens, herons, flycatchers, crows, bluebirds, wrens, warblers, blackbirds, orioles, goldfinches, swallows, sparrows, ducks, quail, grouse, pheasants, hummingbirds, falcons, gulls, and ospreys are some of the other birds that can be found.[19]

Several reptiles can be found, including eleven species of lizards and eight species of snake (including one rattlesnake).[20] The common kingsnake and prairie rattlesnake have been reported in the park, but not confirmed by the National Park Service.[20]

The park is home to six confirmed amphibian species, including the red-spotted toad,[21] Woodhouse's toad,[22] American bullfrog,[23] northern leopard frog,[24] Great Basin spadefoot toad,[25] and tiger salamander.[26] The canyon tree frog was reported to be in the park in 2000, but was not confirmed during a study in 2004.[27]

Climate

The National Weather Service has maintained two cooperative weather stations in the park since June 1965. Official data documents the desert climate with less than 10 inches (250 millimetres) of annual rainfall, as well as very warm, mostly dry summers and cold, occasionally wet winters. Snowfall is generally light during the winter.

The station in The Neck region reports average January temperatures ranging from a high of 37.0 °F (2.8 °C) to a low of 20.7 °F (−6.3 °C). Average July temperatures range from a high of 90.7 °F (32.6 °C) to a low of 65.8 °F (18.8 °C). There are an average of 43.3 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and an average of 124.3 days with lows of 32 °F (0 °C) or lower. The highest recorded temperature was 105 °F (41 °C) on July 15, 2005, and the lowest recorded temperature was −13 °F (−25 °C) on February 6, 1989. Average annual precipitation is 9.07 inches (230 mm). There are an average of 59 days with measurable precipitation. The wettest year was 1984, with 13.66 in (347 mm), and the driest year was 1989, with 4.63 in (118 mm). The most precipitation in one month was 5.19 in (132 mm) in October 2006. The most precipitation in 24 hours was 1.76 in (45 mm) on April 9, 1978. Average annual snowfall is 22.9 in (58 cm). The most snowfall in one year was 47.4 in (120 cm) in 1975, and the most snowfall in one month was 27.0 in (69 cm) in January 1978.[28]

The station in The Needles region reports average January temperatures ranging from a high of 41.2 °F (5.1 °C) to a low of 16.6 °F (−8.6 °C). Average July temperatures range from a high of 95.4 °F (35.2 °C) to a low of 62.4 °F (16.9 °C). There are an average of 75.4 days with highs of 90 °F (32 °C) or higher and an average of 143.6 days with lows of 32 °F (0 °C) or lower. The highest recorded temperature was 107 °F (42 °C) on July 13, 1971, and the lowest recorded temperature was −16 °F (−27 °C) on January 16, 1971. Average annual precipitation is 8.49 in (216 mm). There are an average of 56 days with measurable precipitation. The wettest year was 1969, with 11.19 in (284 mm), and the driest year was 1989, with 4.25 in (108 mm). The most precipitation in one month was 4.43 in (113 mm) in October 1972. The most precipitation in 24 hours was 1.56 in (40 mm) on September 17, 1999. Average annual snowfall is 14.4 in (37 cm). The most snowfall in one year was 39.3 in (100 cm) in 1975, and the most snowfall in one month was 24.0 in (61 cm) in March 1985.[29]

Geology

A subsiding basin and nearby uplifting mountain range (the Uncompahgre) existed in the area in Pennsylvanian time. Seawater trapped in the subsiding basin created thick evaporite deposits by Mid Pennsylvanian. This, along with eroded material from the nearby mountain range, become the Paradox Formation, itself a part of the Hermosa Group. Paradox salt beds started to flow later in the Pennsylvanian and probably continued to move until the end of the Jurassic.[30] Some scientists believe Upheaval Dome was created from Paradox salt bed movement, creating a salt dome, but more modern studies show that the meteorite theory is more likely to be correct.

A warm shallow sea again flooded the region near the end of the Pennsylvanian. Fossil-rich limestones, sandstones, and shales of the gray-colored Honaker Trail Formation resulted. A period of erosion then ensued, creating a break in the geologic record called an unconformity. Early in the Permian an advancing sea laid down the Halgaito Shale. Coastal lowlands later returned to the area, forming the Elephant Canyon Formation.

Large alluvial fans filled the basin where it met the Uncompahgre Mountains, creating the Cutler red beds of iron-rich arkose sandstone. Underwater sand bars and sand dunes on the coast inter-fingered with the red beds and later became the white-colored cliff-forming Cedar Mesa Sandstone. Brightly colored oxidized muds were then deposited, forming the Organ Rock Shale. Coastal sand dunes and marine sand bars once again became dominant, creating the White Rim Sandstone.

A second unconformity was created after the Permian sea retreated. Flood plains on an expansive lowland covered the eroded surface and mud built up in tidal flats, creating the Moenkopi Formation. Erosion returned, forming a third unconformity. The Chinle Formation was then laid down on top of this eroded surface.

Increasingly dry climates dominated the Triassic. Therefore, sand in the form of sand dunes invaded and became the Wingate Sandstone. For a time climatic conditions became wetter and streams cut channels through the sand dunes, forming the Kayenta Formation. Arid conditions returned to the region with a vengeance; a large desert spread over much of western North America and later became the Navajo Sandstone. A fourth unconformity was created by a period of erosion.

Mud flats returned, forming the Carmel Formation and the Entrada Sandstone was laid down next. A long period of erosion stripped away most of the San Rafael Group in the area along with any formations that may have been laid down in the Cretaceous period.

The Laramide orogeny started to uplift the Rocky Mountains 70 million years ago and with it the Canyonlands region. Erosion intensified and when the Colorado River Canyon reached the salt beds of the Paradox Formation the overlying strata extended toward the river canyon, forming features such as The Grabens. Increased precipitation during the ice ages of the Pleistocene quickened the rate of canyon excavation along with other erosion. Similar types of erosion are ongoing, but occur at a slower rate.

Gallery

Windgate Sandstone cliffs in Canyonlands National Park

Windgate Sandstone cliffs in Canyonlands National Park The White Rim Sandstone

The White Rim Sandstone.jpg) Canyonlands at daybreak. La Sal Mountains in background

Canyonlands at daybreak. La Sal Mountains in background False Kiva stone circle

False Kiva stone circle Petroglyphs, Horse Canyon, The Maze. 1962 photo

Petroglyphs, Horse Canyon, The Maze. 1962 photo The Great Gallery, Horseshoe Canyon

The Great Gallery, Horseshoe Canyon The White Rim in Canyonlands National Park

The White Rim in Canyonlands National Park Mesa Arch at sunrise, Island in the Sky district

Mesa Arch at sunrise, Island in the Sky district The view from the Island In The Sky overlooking the Colorado River

The view from the Island In The Sky overlooking the Colorado River Druid Arch in the Needles district

Druid Arch in the Needles district Raft in the Big Drop Rapids, Cataract Canyon

Raft in the Big Drop Rapids, Cataract Canyon A view from Grand View Point Overlook toward Monument Basin

A view from Grand View Point Overlook toward Monument Basin

Further reading

- Harris, Ann C. (1998). Geology of National Parks. Kendall Hunt Publishing Co. ISBN 0-7872-5353-7.

- Zwinger, Ann (1986). Wind in the Rock. Tucson, AZ: University of Arizona Press. ISBN 978-0-8165-0985-0.

- Johnson, David (1989). Canyonlands: The Story Behind the Scenery. Las Vegas, NV: KC Publications. ISBN 0-88714-034-3.

- The National Parks: Index 2009–2011 (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

References

- ↑ "Listing of acreage as of December 31, 2011". Land Resource Division, National Park Service. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- 1 2 "Canyonlands NP Recreation Visitors". National Park Service. March 28, 2016. Archived from the original on September 26, 2016. Retrieved May 10, 2016.

- ↑ "Canyonlands Visitor Guide 2014" (PDF). National Park Service. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 14, 2014. Retrieved September 25, 2014.

- ↑ "Canyonlands". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ↑ Abbey, Edward (2006). Postcards from Ed: Dispatches and Salvos from an American Iconoclast. Milkweed Press. p. 175. ISBN 1-57131-284-6.

- ↑ "Day-use permits". National Park Service. 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ "NPS proposes permit system for White Rim and Elephant Hill". Moab Sun News, Moab, Utah. 2015-03-26. Retrieved 2016-01-26.

- ↑ "Visitation". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ↑ Keiter, Robert B.; Stephen Trimble (2008–2009). "Canyonlands Completion report: Negotiating the Borders". University of Utah. Retrieved 2011-06-09.

- ↑ "Native Americans". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ↑ "Maze". National Park Service. Retrieved 2008-08-21.

- ↑ "Geology Footnotes". Explore Nature. National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ Geib, Phil R.; Michael R. Robins. "Analysis and Dating of the Great Gallery Tool and Food Bag". National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- 1 2 3 Hitchman, Robert. "The Great Gallery of Horseshoe Canyon". Apogee Photo Magazine. Archived from the original on 2008-03-04. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ "The Archeology of Horseshoe Canyon" (PDF). National Park Service. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ "Species List - Mammals - Canyonlands National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Mammals - Canyonlands National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Birds - Canyonlands National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Species List - Birds - Canyonlands National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- 1 2 "Species List - Reptiles - Canyonlands National Park". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Bufo punctatus - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Present". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Bufo woodhousii - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Present". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Rana catesbeiana - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Present". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Rana pipiens - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Present". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Spea intermontana - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Present". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Ambystoma tigrinum - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Present". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Species Profile - Hyla arenicolor - Canyonlands National Park (CANY) - Unconfirmed". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 30, 2016. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ↑ "Canyonlands The Neck, Utah". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ "Canyonlands The Needle, Utah". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved 2011-06-11.

- ↑ Harris, Ann C. (1998). Geology of National Parks. Kendall Hunt Publishing Co. ISBN 0-7872-5353-7.

External links

- Official website by the National Park Service

- Canyonlands Field Institute (a non-profit support group)

- Canyonlands Natural History Association (a non-profit organization established to assist the scientific and educational efforts of the NPS)

- Spherical panoramas of Canyonlands

- DigitalCommons@USU (Canyonlands Research Publications from Utah State University)