Progesterone (medication)

Progesterone is a medication and naturally occurring steroid hormone.[9] It is a progestogen and neurosteroid is used mainly in hormone replacement therapy (HRT) for menopause,[9] hypogonadism, and in transgender women. Progesterone can be taken by mouth, in through the vagina, by injection into muscle, or through the use of an implant that is placed under the skin, among other routes.[9]

Progesterone was first isolated in pure form in 1934.[10][11] It first became available as a medication in 1934.[12][13] Micronized progesterone, which allowed progesterone to be taken by mouth, was not introduced until 1980.[13][14][15] A large number of synthetic progestogens, or progestins, have been developed from progesterone and are used as medications as well. Progesterone is on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines, the most important medications needed in a basic health system.[16]

Medical uses

The use of progesterone and its analogues have many medical applications, both to address acute situations and to address the long-term decline of natural progesterone levels. Because of the poor bioavailability of progesterone when taken by mouth, many synthetic progestins have been designed with improved bioavailability by mouth and have been used long before progesterone formulations became available.[17]

Hormone replacement therapy

Transgender

Progesterone is used as a component of hormone replacement therapy for transgender women.[18]

Prevention of preterm birth

Vaginally dosed progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in preventing preterm birth in women at risk for preterm birth. The initial study by Fonseca suggested that vaginal progesterone could prevent preterm birth in women with a history of preterm birth.[19] According to a recent study, women with a short cervix that received hormonal treatment with a progesterone gel had their risk of prematurely giving birth reduced. The hormone treatment was administered vaginally every day during the second half of a pregnancy.[20] A subsequent and larger study showed that vaginal progesterone was no better than placebo in preventing recurrent preterm birth in women with a history of a previous preterm birth,[21] but a planned secondary analysis of the data in this trial showed that women with a short cervix at baseline in the trial had benefit in two ways: a reduction in births less than 32 weeks and a reduction in both the frequency and the time their babies were in intensive care.[22] In another trial, vaginal progesterone was shown to be better than placebo in reducing preterm birth prior to 34 weeks in women with an extremely short cervix at baseline.[23] An editorial by Roberto Romero discusses the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment.[24] A meta-analysis published in 2011 found that vaginal progesterone cut the risk of premature births by 42 percent in women with short cervixes.[25] The meta-analysis, which pooled published results of five large clinical trials, also found that the treatment cut the rate of breathing problems and reduced the need for placing a baby on a ventilator.[26]

Fertility indications

- Progesterone is used for luteal support in assisted reproductive technology (ART) cycles such as in-vitro fertilization (IVF).

- Progesterone is used to prepare uterine lining in infertility therapy and to support early pregnancy.

Gynecological disorders

- Progesterone is used to control persistent anovulatory bleeding.

- Progesterone is used in non-pregnant women with a delayed menstruation of one or more weeks, in order to allow the thickened endometrial lining to slough off. This process is termed a progesterone withdrawal bleed. The progesterone is taken orally for a short time (usually one week), after which the progesterone is discontinued and bleeding should occur.

Other uses

- Progesterone can be used to treat catamenial epilepsy by supplementation during certain periods of the menstrual cycle.[27]

- Progesterone is being investigated as potentially beneficial in treating multiple sclerosis, since the characteristic deterioration of nerve myelin insulation halts during pregnancy, when progesterone levels are raised; deterioration commences again when the levels drop.

Medical formulations

Progesterone is marketed under a large number of different brand names throughout the world.[28] Progesterone was approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration as vaginal gel on July 31, 1997,[29] a capsule to be taken by mouth on May 14, 1998[30] in an injection form on April 25, 2001[31] and as a vaginal insert on June 21, 2007.[32] Progesterone, when taken by mouth, has very poor pharmacokinetics, including low bioavailability (only about 10–15% reaches the bloodstream)[33] and a half-life of only about 5 minutes, unless it is micronized.[5][34] As such, it is sold in the form of oil-filled capsules containing micronized progesterone for oral use, termed oral micronized progesterone (OMP).[5][28] Progesterone is also available in the forms of vaginal or rectal suppositories or pessaries,[28] transdermally-administered gels or creams,[28][35] or via intramuscular or subcutaneous injection of a vegetable oil solution.[5][28][36]

Transdermal products made with progesterone USP (i.e., "natural progesterone") do not require a prescription. Some of these products also contain "wild yam extract" derived from Dioscorea villosa, but there is no evidence that the human body can convert its active ingredient (diosgenin, the plant steroid that is chemically converted to produce progesterone industrially)[37] into progesterone.[38][39]

Interactions

There are several notable drug interactions with progesterone. Certain selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) may increase the GABAA receptor-related central depressant effects of progesterone by enhancing its conversion into 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone via activation of 3α-HSD.[40] Progesterone potentiates the sedative effects of benzodiazepines and ethanol.[41] Notably, there is a case report of progesterone abuse alone with very high doses.[42] 5α-Reductase inhibitors such as finasteride and dutasteride, as well as inhibitors of 3α-HSD such as medroxyprogesterone acetate, inhibit the conversion of progesterone into its inhibitory neurosteroid metabolites, and for this reason, may have the potential to block or reduce its sedative effects.[43][44][45]

Progesterone is a weak but significant agonist of the pregnane X receptor (PXR), and has been found to induce several hepatic cytochrome P450 enzymes, such as CYP3A4, especially when concentrations are high, such as with pregnancy range levels.[46][47][48][49] As such, progesterone may have the potential to accelerate the clearance of various drugs, especially with oral administration (which results in supraphysiological levels of progesterone in the liver), as well as with the high concentrations achieved with sufficient injection dosages.

Pharmacology

Progesterone is a progestogen, or an agonist of the nuclear progesterone receptors (PRs), the PR-A and the PR-B.[9] It is also an agonist of the membrane progesterone receptors (mPRs), such as the mPRα, mPRβ, and mPRγ.[50][51] Progesterone is a potent antimineralocorticoid[52][53] as well as a very weak glucocorticoid as well.[54][55] In addition to interactions with nuclear receptors, progesterone is a neurosteroid;[56] it is an antagonist of the σ1 receptor,[57][58] a negative allosteric modulator of the nicotinic acetylcholine receptor,[56] and, through active metabolites such as allopregnanolone, a potent positive allosteric modulator of the GABAA receptor.[59]

Pharmacokinetics

Oral administration

The route of administration impacts the effects of progesterone. OMP has a wide inter-individual variability in absorption and bioavailability. In contrast, progestins are rapidly absorbed with a longer half-life than progesterone and maintain stable levels in the blood.[60] The absorption and bioavailability of OMP is increased approximately two-fold when it is taken with food.[61] Progesterone has a relatively short half-life in the body. As such, OMP is usually prescribed for twice or thrice-daily administration or once-daily administration when taken by injection.[5] Via the oral route, peak concentrations are seen about 2–3 hours after ingestion, and the half-life is about 16–18 hours.[5] Significantly elevated serum levels of progesterone are maintained for about 12 hours, and levels do not return to baseline until at least 24 hours have passed.[5] OMP is prescribed in divided doses .[62]

Neurosteroids metabolites

A portion of progesterone is converted into 5α-dihydroprogesterone and allopregnanolone (a conversion that is catalyzed by the enzymes 5α-reductase and 3α-hydroxysteroid dehydrogenase (3α-HSD) and occurs in the liver, reproductive endocrine tissues, skin, and the brain),[63] which are neurosteroids and potent potentiators of GABAA receptors.[64][65] It is for this reason that common reported side effects of progesterone include dizziness, drowsiness or sedation, sleepiness, and fatigue, especially at high doses.[64][65] As a result, some physicians may instruct their patients to take their progesterone before bed.[64] Both oral and intramuscularly injected progesterone produce sedative effects, indicating that first-pass metabolism in the liver is not essential for the conversion to take place.[66][67][68] Moreover, the sedative effects occur in both men and women, indicating a lack of sex-specificity of the effects.[66]

Vaginal administration

With vaginal and rectal administration, a 100 mg dose of progesterone results in peak levels at 4 hours and 8 hours after dosing, respectively, with the levels achieved being in the serum luteal phase range.[69] Following peak serum concentrations, there is a gradual decline in plasma levels, and after 24 hours, serum levels typical of the follicular phase are reached.[69]

Transdermal administration

Transdermal progesterone is about 5–7 times stronger than oral progesterone.[33] This is due to the fact transdermal administration bypasses first-pass metabolism.[33] As such, 20–30 mg/day transdermal progesterone is equivalent to about 100–200 mg/day oral progesterone.[33] Some researchers have reported that absorption of progesterone via the transdermal route is poor, impractical, and unsubstantiated, however they may have been measuring serum blood or urine levels.[70][71] Other studies have shown that transdermal absorption of progesterone cream is much higher when capillary blood or saliva testing is used.[72]

Intramuscular injection

With intramuscular injection of 10 mg progesterone suspended in vegetable oil, maximum plasma concentrations (Cmax) are reached at approximately 8 hours after administration, and serum levels remain above baseline for about 24 hours.[36] Doses of 10 mg, 25 mg, and 50 mg via intramuscular injection result in mean maximum serum concentrations of 7 ng/mL, 28 ng/mL, and 50 ng/mL, respectively.[36] With intramuscular injection, a dose of 25 mg results in normal luteal phase serum levels of progesterone within 8 hours, and a 100 mg dose produces mid-pregnancy levels.[69] At these doses, serum levels of progesterone remain elevated above baseline for at least 48 hours,[69] with a half-life of about 22 hours.[6]

Due to the high concentrations achieved, progesterone by intramuscular injection at the usual clinical dose range is able to suppress gonadotropin secretion from the pituitary gland, demonstrating antigonadotropic efficacy (and therefore suppression of gonadal sex steroid production).[36]

Intramuscular progesterone irritates tissues and is associated with injection site reactions such as changes in skin color, pain, redness, transient indurations (due to inflammation), ecchymosis (bruising/discoloration), and others.[73]

Microsphere formulation

An intramuscular suspension formulation of progesterone contained in microspheres is marketed under the brand name ProSphere in Mexico.[73][74][75] It is far longer-lasting than regular intramuscular progesterone and is administered once weekly or monthly, depending on the indication.[73]

Subcutaneous injection

Progesterone can also be administered alternatively via subcutaneous injection, with the aqueous formulation Prolutex in Europe being intended specifically for once-daily administration by this route.[6][76][77] This formulation is rapidly absorbed and has been found to result in higher serum peak progesterone levels relative to intramuscular oil formulations.[77] In addition, subcutaneous injection of progesterone is considered to be easier, safer (less risk of injection site reactions), and less painful relative to intramuscular injection.[77] The terminal half-life of this formulation is 13 to 18 hours, which is similar to the terminal half-lives of OMP and intramuscular progesterone.[6]

Normal progesterone levels

For comparative purposes, mid-luteal serum levels of progesterone are above 5–9 ng/ml,[69] plasma levels in the first 4 to 8 weeks of pregnancy are 25–75 ng/ml,[10] and serum levels at term are typically around 200 ng/ml.[10] Production of progesterone in the body in late pregnancy is approximately 250 mg per day, 90% of which reaches maternal circulation.[78]

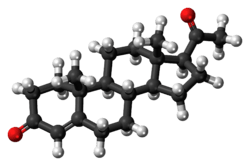

Chemistry

Progesterone is a pregnane (C21) steroid and is also known as pregn-4-ene-3,20-dione. It has a double bond (4-ene) between the C4 and C5 positions and two ketone groups (3,20-dione), one at the C3 position and the other at the C20 position.

Like all unconjugated steroid hormones, progesterone is lipophilic and hydrophobic.

Derivatives

A large number of progestins (synthetic progestogens) have been derived from progesterone. They can be categorized into several structural groups, including derivatives of retroprogesterone, 17α-hydroxyprogesterone, 17α-methylprogesterone, and 19-norprogesterone, with a respective example from each group including dydrogesterone, medroxyprogesterone acetate, medrogestone, and promegestone. Quingestrone is a rare example that does not belong to any of these groups.

History

The hormonal action of progesterone was discovered in 1929.[10][11][79] In 1934, pure crystalline progesterone was isolated in 1934 and its chemical structure was determined.[10][11] Later that year, chemical synthesis of progesterone was accomplished.[11][80] Shortly following its chemical synthesis, progesterone began being tested clinically in women.[11] In 1934, Schering introduced progesterone as a pharmaceutical drug under the brand name Proluton.[12][13] It was administered by intramuscular injection because it progesterone rapidly inactivated after being taken by mouth and when used by mouth required very high doses to produce an effect.[14][81]

It was not until almost half a century later that a non-injected formulation of progesterone was marketed.[82] Micronization, similarly to the case of estradiol, allowed progesterone to be absorbed effectively via other routes of administration, but the micronization process was difficult for manufacturers for many years.[83] Oral micronized progesterone was finally marketed in France under the brand name Utrogestan in 1980,[13][14][15] and this was followed by the introduction of oral micronized progesterone in the United States under the brand name Prometrium in 1998.[83] In the early 1990s, vaginal micronized progesterone (brand names Crinone, Utrogestan, Endometrin)[84] was also marketed.[82]

Society and culture

Generic name

Progesterone is the generic name of progesterone in English and the INN, USAN, USP,[85] BAN, DCIT, and JAN of the drug, while progestérone is the name of progesterone in French and the DCF.[86][87][88][89] It is also formally referred to as progesteronum in Latin, progesterona in Spanish and Portuguese, and progesteron in German.[86]

Brand names

Progesterone is marketed under a large number of brand names throughout the world.[88][86] Examples of major brand names in which progesterone has been marketed include Crinone, Crinone 8%, Cyclogest, Endometrin, Geslutin, Gesterol, Gestone, Luteinol, Lutigest, Lutinus, Progeffik, Progelan, Progendo, Progest, Progestaject, Progestan, Progestin, Progestogel, Prolutex, Proluton, Prometrium, Prontogest, Utrogest, and Utrogestan.[88][86]

Availability

United States

As of November 2016, progesterone is available in the United States in the following formulations:[90]

- Oral capsules: Prometrium – 100 mg, 200 mg, 300 mg

- Vaginal gels: Crinone, Progestasert, Prometrium – 4%, 8%

- Vaginal inserts: Endometrin – 100 mg

- Oil for intramuscular injection: Progesterone – 50 mg/mL

Discontinued:

- Oil for intramuscular injection: Progesterone – 25 mg/mL

- Intrauterine device: Progestasert – 38 mg/device

A combination formulation of micronized progesterone and estradiol in oil-filled oral capsules (TX-001HR) is currently under development in the U.S. for the treatment of menopausal symptoms and endometrial hyperplasia, though it has yet to be approved or introduced.[91][92]

Progesterone is also available in custom preparations from compounding pharmacies in the U.S.[93] This includes subcutaneous pellet implants.[94]

Other countries

Progesterone is widely available in countries throughout the world in a variety of formulations. For an extensive list of countries that it is marketed in along with the associated brand names, see here.

Research

Brain damage

Studies as far back as 1987 show that female sex hormones have an effect on the recovery of traumatic brain injury.[95] In these studies, it was first observed that pseudopregnant female rats had reduced edema after traumatic brain injury. Recent clinical trials have shown that among patients that have suffered moderate traumatic brain injury, those that have been treated with progesterone are more likely to have a better outcome than those who have not.[96] A number of additional animal studies have confirmed that progesterone has neuroprotective effects when administered shortly after traumatic brain injury.[97] Encouraging results have also been reported in human clinical trials.[98][99]

Combination treatments

Vitamin D and progesterone separately have neuroprotective effects after traumatic brain injury, but when combined their effects are synergistic.[100] When used at their optimal respective concentrations, the two combined have been shown to reduce cell death more than when alone.

One study looks at a combination of progesterone with estrogen. Both progesterone and estrogen are known to have antioxidant-like qualities and are shown to reduce edema without injuring the blood-brain barrier. In this study, when the two hormones are administered alone it does reduce edema, but the combination of the two increases the water content, thereby increasing edema.[101]

Clinical trials

The clinical trials for progesterone as a treatment for traumatic brain injury have only recently begun. ProTECT, a phase II trial conducted in Atlanta at Grady Memorial Hospital in 2007, the first to show that progesterone reduces edema in humans. Since then, trials have moved on to phase III. The National Institute of Health began conducting a nationwide phase III trial in 2011 led by Emory University.[96] A global phase III initiative called SyNAPSe®, initiated in June 2010, is run by a U.S.-based private pharmaceutical company, BHR Pharma, and is being conducted in the United States, Argentina, Europe, Israel and Asia.[102][103] Approximately 1,200 patients with severe (Glasgow Coma Scale scores of 3-8), closed-head TBI will be enrolled in the study at nearly 150 medical centers.

Addiction

To examine the effects of progesterone on nicotine addiction, participants in one study were either treated orally with a progesterone treatment, or treated with a placebo. When treated with progesterone, participants exhibited enhanced suppression of smoking urges, reported higher ratings of “bad effects” from IV nicotine, and reported lower ratings of “drug liking”. These results suggest that progesterone not only alters the subjective effects of nicotine, but reduces the urge to smoke cigarettes.[104]

References

- 1 2 Stanczyk FZ (September 2002). "Pharmacokinetics and potency of progestins used for hormone replacement therapy and contraception". Reviews in Endocrine & Metabolic Disorders. 3 (3): 211–24. doi:10.1023/A:1020072325818. PMID 12215716.

- 1 2 3 Simon JA, Robinson DE, Andrews MC, Hildebrand JR, Rocci ML, Blake RE, Hodgen GD (July 1993). "The absorption of oral micronized progesterone: the effect of food, dose proportionality, and comparison with intramuscular progesterone". Fertility and Sterility. 60 (1): 26–33. doi:10.1016/S0015-0282(16)56031-2. PMID 8513955.

- ↑ Fritz MA, Speroff L (28 March 2012). Clinical Gynecologic Endocrinology and Infertility. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 44–. ISBN 978-1-4511-4847-3.

- ↑ Marshall WJ, Marshall WJ, Bangert SK (2008). Clinical Chemistry. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 192–. ISBN 0-7234-3455-7.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Zutshi (1 January 2005). Hormones in Obstetrics and Gynaecology. Jaypee Brothers Publishers. p. 74. ISBN 978-81-8061-427-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cometti B (November 2015). "Pharmaceutical and clinical development of a novel progesterone formulation". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 94 Suppl 161: 28–37. doi:10.1111/aogs.12765. PMID 26342177.

- ↑ Adler N, Pfaff D, Goy RW (6 Dec 2012). Handbook of Behavioral Neurobiology Volume 7 Reproduction (1st ed.). New York: Plenum Press. p. 189. ISBN 978-1-4684-4834-4. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- ↑ "progesterone (CHEBI:17026)". ChEBI. European Molecular Biology Laboratory-EBI. Retrieved 4 July 2015.

- 1 2 3 4 Kuhl H (2005). "Pharmacology of estrogens and progestogens: influence of different routes of administration". Climacteric. 8 Suppl 1: 3–63. doi:10.1080/13697130500148875. PMID 16112947.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Josimovich J (11 November 2013). Gynecologic Endocrinology. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 9, 25–29. ISBN 978-1-4613-2157-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Coutinho EM, Segal SJ (1999). Is Menstruation Obsolete?. Oxford University Press. pp. 31–. ISBN 978-0-19-513021-8.

- 1 2 Seaman B (4 January 2011). The Greatest Experiment Ever Performed on Women: Exploding the Estrogen Myth. Seven Stories Press. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-1-60980-062-8.

- 1 2 3 4 Simon JA (December 1995). "Micronized progesterone: vaginal and oral uses". Clinical Obstetrics and Gynecology. 38 (4): 902–14. doi:10.1097/00003081-199538040-00024. PMID 8616985.

- 1 2 3 Ruan X, Mueck AO (November 2014). "Systemic progesterone therapy--oral, vaginal, injections and even transdermal?". Maturitas. 79 (3): 248–55. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2014.07.009. PMID 25113944.

- 1 2 Csech J, Gervais C (September 1982). "[Utrogestan]". Soins. Gynécologie, Obstétrique, Puériculture, Pédiatrie (in French) (16): 45–6. PMID 6925387.

- ↑ "19th WHO Model List of Essential Medicines (April 2015)" (PDF). WHO. April 2015. Retrieved May 10, 2015.

- ↑ Schindler AE, Campagnoli C, Druckmann R, Huber J, Pasqualini JR, Schweppe KW, Thijssen JH (2008). "Classification and pharmacology of progestins" (PDF). Maturitas. 61 (1-2): 171–80. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2008.11.013. PMID 19434889.

- ↑ World Professional Association for Transgender Health (September 2011), Standards of Care for the Health of Transsexual, Transgender, and Gender Nonconforming People, Seventh Version (PDF)

- ↑ da Fonseca EB, Bittar RE, Carvalho MH, Zugaib M (February 2003). "Prophylactic administration of progesterone by vaginal suppository to reduce the incidence of spontaneous preterm birth in women at increased risk: a randomized placebo-controlled double-blind study". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 188 (2): 419–24. doi:10.1067/mob.2003.41. PMID 12592250.

- ↑ Harris, Gardiner (2011-05-02). "Hormone Is Said to Cut Risk of Premature Birth". New York Times. Retrieved 5 May 2011.

- ↑ O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Defranco EA, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schackis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW (October 2007). "Progesterone vaginal gel for the reduction of recurrent preterm birth: primary results from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 687–96. doi:10.1002/uog.5158. PMID 17899572.

- ↑ DeFranco EA, O'Brien JM, Adair CD, Lewis DF, Hall DR, Fusey S, Soma-Pillay P, Porter K, How H, Schakis R, Eller D, Trivedi Y, Vanburen G, Khandelwal M, Trofatter K, Vidyadhari D, Vijayaraghavan J, Weeks J, Dattel B, Newton E, Chazotte C, Valenzuela G, Calda P, Bsharat M, Creasy GW (October 2007). "Vaginal progesterone is associated with a decrease in risk for early preterm birth and improved neonatal outcome in women with a short cervix: a secondary analysis from a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 697–705. doi:10.1002/uog.5159. PMID 17899571.

- ↑ Fonseca EB, Celik E, Parra M, Singh M, Nicolaides KH (August 2007). "Progesterone and the risk of preterm birth among women with a short cervix". The New England Journal of Medicine. 357 (5): 462–9. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa067815. PMID 17671254.

- ↑ Romero R (October 2007). "Prevention of spontaneous preterm birth: the role of sonographic cervical length in identifying patients who may benefit from progesterone treatment". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 30 (5): 675–86. doi:10.1002/uog.5174. PMID 17899585.

- ↑ Hassan SS, Romero R, Vidyadhari D, Fusey S, Baxter JK, Khandelwal M, Vijayaraghavan J, Trivedi Y, Soma-Pillay P, Sambarey P, Dayal A, Potapov V, O'Brien J, Astakhov V, Yuzko O, Kinzler W, Dattel B, Sehdev H, Mazheika L, Manchulenko D, Gervasi MT, Sullivan L, Conde-Agudelo A, Phillips JA, Creasy GW (July 2011). "Vaginal progesterone reduces the rate of preterm birth in women with a sonographic short cervix: a multicenter, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Ultrasound in Obstetrics & Gynecology. 38 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1002/uog.9017. PMC 3482512

. PMID 21472815. Lay summary – WebMD.

. PMID 21472815. Lay summary – WebMD. - ↑ "Progesterone helps cut risk of pre-term birth". Women's health. msnbc.com. 2011-12-14. Retrieved 2011-12-14.

- ↑ Devinsky O, Schachter S, Pacia S (1 January 2005). Complementary and Alternative Therapies for Epilepsy. Demos Medical Publishing. pp. 378–. ISBN 978-1-934559-08-6.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. p. 880. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 020701". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 019781". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 075906". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- ↑ "Orange Book: Approved Drug Products with Therapeutic Equivalence Evaluations: 022057". Food and Drug Administration. 2010-07-02. Retrieved 2010-07-07.

- 1 2 3 4 Arun N, Narendra M, Shikha S (15 December 2012). Progress in Obstetrics and Gynecology--3. Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers Pvt. Ltd. pp. 370–. ISBN 978-93-5090-575-3.

- ↑ King TL, Brucker MC (25 October 2010). Pharmacology for Women's Health. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 372–373. ISBN 978-1-4496-5800-7.

- ↑ Lark S (1999). Making the Estrogen Decision. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 22. ISBN 9780879836962.

- 1 2 3 4 Progesterone - Drugs.com, retrieved 2015-08-23

- ↑ Marker RE, Krueger J (1940). "Sterols. CXII. Sapogenins. XLI. The Preparation of Trillin and its Conversion to Progesterone". J. Am. Chem. Soc. 62 (12): 3349–3350. doi:10.1021/ja01869a023.

- ↑ Zava DT, Dollbaum CM, Blen M (March 1998). "Estrogen and progestin bioactivity of foods, herbs, and spices". Proceedings of the Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. Society for Experimental Biology and Medicine. 217 (3): 369–78. doi:10.3181/00379727-217-44247. PMID 9492350.

- ↑ Komesaroff PA, Black CV, Cable V, Sudhir K (June 2001). "Effects of wild yam extract on menopausal symptoms, lipids and sex hormones in healthy menopausal women". Climacteric. 4 (2): 144–50. doi:10.1080/713605087. PMID 11428178.

- ↑ Pinna G, Agis-Balboa RC, Pibiri F, Nelson M, Guidotti A, Costa E (October 2008). "Neurosteroid biosynthesis regulates sexually dimorphic fear and aggressive behavior in mice". Neurochemical Research. 33 (10): 1990–2007. doi:10.1007/s11064-008-9718-5. PMID 18473173.

- ↑ Babalonis S, Lile JA, Martin CA, Kelly TH (June 2011). "Physiological doses of progesterone potentiate the effects of triazolam in healthy, premenopausal women". Psychopharmacology. 215 (3): 429–39. doi:10.1007/s00213-011-2206-7. PMID 21350928.

- ↑ "Progesterone abuse". Reactions Weekly. Springer International Publishing. 599 (1): 9. 1996. doi:10.2165/00128415-199605990-00031. ISSN 1179-2051.

- ↑ Traish AM, Mulgaonkar A, Giordano N (June 2014). "The dark side of 5α-reductase inhibitors' therapy: sexual dysfunction, high Gleason grade prostate cancer and depression". Korean Journal of Urology. 55 (6): 367–79. doi:10.4111/kju.2014.55.6.367. PMC 4064044

. PMID 24955220.

. PMID 24955220. - ↑ Meyer L, Venard C, Schaeffer V, Patte-Mensah C, Mensah-Nyagan AG (April 2008). "The biological activity of 3alpha-hydroxysteroid oxido-reductase in the spinal cord regulates thermal and mechanical pain thresholds after sciatic nerve injury". Neurobiology of Disease. 30 (1): 30–41. doi:10.1016/j.nbd.2007.12.001. PMID 18291663.

- ↑ Pazol K, Wilson ME, Wallen K (June 2004). "Medroxyprogesterone acetate antagonizes the effects of estrogen treatment on social and sexual behavior in female macaques". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 89 (6): 2998–3006. doi:10.1210/jc.2003-032086. PMC 1440328

. PMID 15181090.

. PMID 15181090. - ↑ Meanwell NA (8 December 2014). Tactics in Contemporary Drug Design. Springer. pp. 161–. ISBN 978-3-642-55041-6.

- ↑ Legato MJ, Bilezikian JP (2004). Principles of Gender-specific Medicine. Gulf Professional Publishing. pp. 146–. ISBN 978-0-12-440906-4.

- ↑ Lemke TL, Williams DA (24 January 2012). Foye's Principles of Medicinal Chemistry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. pp. 164–. ISBN 978-1-60913-345-0.

- ↑ Estrogens—Advances in Research and Application: 2013 Edition: ScholarlyBrief. ScholarlyEditions. 21 June 2013. pp. 4–. ISBN 978-1-4816-7550-5.

- ↑ Soltysik K, Czekaj P (April 2013). "Membrane estrogen receptors - is it an alternative way of estrogen action?". J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 64 (2): 129–42. PMID 23756388.

- ↑ Prossnitz ER, Barton M (May 2014). "Estrogen biology: New insights into GPER function and clinical opportunities". Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 389 (1–2): 71–83. doi:10.1016/j.mce.2014.02.002. PMC 4040308

. PMID 24530924.

. PMID 24530924. - ↑ Rupprecht R, Reul JM, van Steensel B, Spengler D, Söder M, Berning B, Holsboer F, Damm K (October 1993). "Pharmacological and functional characterization of human mineralocorticoid and glucocorticoid receptor ligands". European Journal of Pharmacology. 247 (2): 145–54. doi:10.1016/0922-4106(93)90072-H. PMID 8282004.

- ↑ Elger W, Beier S, Pollow K, Garfield R, Shi SQ, Hillisch A (2003). "Conception and pharmacodynamic profile of drospirenone". Steroids. 68 (10-13): 891–905. doi:10.1016/j.steroids.2003.08.008. PMID 14667981.

- ↑ Attardi BJ, Zeleznik A, Simhan H, Chiao JP, Mattison DR, Caritis SN (2007). "Comparison of progesterone and glucocorticoid receptor binding and stimulation of gene expression by progesterone, 17-alpha hydroxyprogesterone caproate, and related progestins". Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 197 (6): 599.e1–7. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2007.05.024. PMC 2278032

. PMID 18060946.

. PMID 18060946. - ↑ Lei K, Chen L, Georgiou EX, Sooranna SR, Khanjani S, Brosens JJ, Bennett PR, Johnson MR (2012). "Progesterone acts via the nuclear glucocorticoid receptor to suppress IL-1β-induced COX-2 expression in human term myometrial cells". PloS One. 7 (11): e50167. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0050167. PMID 23209664.

- 1 2 Baulieu E, Schumacher M (2000). "Progesterone as a neuroactive neurosteroid, with special reference to the effect of progesterone on myelination". Steroids. 65 (10-11): 605–12. doi:10.1016/s0039-128x(00)00173-2. PMID 11108866.

- ↑ Maurice T, Urani A, Phan VL, Romieu P (November 2001). "The interaction between neuroactive steroids and the sigma1 receptor function: behavioral consequences and therapeutic opportunities". Brain Research. Brain Research Reviews. 37 (1-3): 116–32. doi:10.1016/s0165-0173(01)00112-6. PMID 11744080.

- ↑ Johannessen M, Fontanilla D, Mavlyutov T, Ruoho AE, Jackson MB (February 2011). "Antagonist action of progesterone at σ-receptors in the modulation of voltage-gated sodium channels". American Journal of Physiology. Cell Physiology. 300 (2): C328–37. doi:10.1152/ajpcell.00383.2010. PMC 3043630

. PMID 21084640.

. PMID 21084640. - ↑ Paul SM, Purdy RH (March 1992). "Neuroactive steroids". FASEB Journal. 6 (6): 2311–22. PMID 1347506.

- ↑ Schindler AE, Campagnoli C, Druckmann R, Huber J, Pasqualini JR, Schweppe KW, Thijssen JH (December 2003). "Classification and pharmacology of progestins". Maturitas. 46 Suppl 1: S7–S16. doi:10.1016/j.maturitas.2003.09.014. PMID 14670641.

- ↑ Simon JA, Robinson DE, Andrews MC, Hildebrand JR, Rocci ML, Blake RE, Hodgen GD (July 1993). "The absorption of oral micronized progesterone: the effect of food, dose proportionality, and comparison with intramuscular progesterone". Fertility and Sterility. 60 (1): 26–33. PMID 8513955.

- ↑ Integrative Medicine. Elsevier Health Sciences. 2012. p. 343. ISBN 1-4377-1793-4.

- ↑ Reddy DS (2010). "Neurosteroids: endogenous role in the human brain and therapeutic potentials". Progress in Brain Research. 186: 113–37. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00008-7. PMC 3139029

. PMID 21094889.

. PMID 21094889. - 1 2 3 Wang-Cheng R, Neuner JM, Barnabei VM (2007). Menopause. ACP Press. p. 97. ISBN 978-1-930513-83-9.

- 1 2 Bergemann N, Ariecher-Rössler A (27 December 2005). Estrogen Effects in Psychiatric Disorders. Springer Science & Business Media. p. 179. ISBN 978-3-211-27063-9.

- 1 2 Söderpalm AH, Lindsey S, Purdy RH, Hauger R, Wit de H (2004). "Administration of progesterone produces mild sedative-like effects in men and women". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 29 (3): 339–54. doi:10.1016/s0306-4530(03)00033-7. PMID 14644065.

- ↑ de Wit H, Schmitt L, Purdy R, Hauger R (2001). "Effects of acute progesterone administration in healthy postmenopausal women and normally-cycling women". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 26 (7): 697–710. doi:10.1016/s0306-4530(01)00024-5. PMID 11500251.

- ↑ van Broekhoven F, Bäckström T, Verkes RJ (2006). "Oral progesterone decreases saccadic eye velocity and increases sedation in women". Psychoneuroendocrinology. 31 (10): 1190–9. doi:10.1016/j.psyneuen.2006.08.007. PMID 17034954.

- 1 2 3 4 5 van Keep P, Utian W (6 December 2012). The Premenstrual Syndrome: Proceedings of a workshop held during the Sixth International Congress of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynecology, Berlin, September 1980. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 51–52. ISBN 978-94-011-6255-5.

- ↑ Unfer V, Casini ML, Marelli G, Costabile L, Gerli S, Di Renzo GC (August 2005). "Different routes of progesterone administration and polycystic ovary syndrome: a review of the literature". Gynecological Endocrinology. 21 (2): 119–27. doi:10.1080/09513590500170049. PMID 16109599.

- ↑ Elshafie MA, Ewies AA (2007). "Transdermal natural progesterone cream for postmenopausal women: inconsistent data and complex pharmacokinetics". Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology : the Journal of the Institute of Obstetrics and Gynaecology. 27 (7): 655–9. doi:10.1080/01443610701582727. PMID 17999287.

- ↑ Du, JY; Sanchez, P; Kim, L; Azen, CG; Zava, DT; Stanczyk, FZ (November 2013). "Percutaneous progesterone delivery via cream or gel application in postmenopausal women: a randomized cross-over study of progesterone levels in serum, whole blood, saliva, and capillary blood.". Menopause (New York, N.Y.). 20 (11): 1169–75. PMID 23652031.

- 1 2 3 Bernardo-Escudero R, Cortés-Bonilla M, Alonso-Campero R, Francisco-Doce MT, Chavarín-González J, Pimentel-Martínez S, Zambrano-Tapia L (2012). "Observational study of the local tolerability of injectable progesterone microspheres". Gynecol. Obstet. Invest. 73 (2): 124–9. doi:10.1159/000330711. PMID 21997608.

- ↑ Tobías, G. M., Usabiaga, R. A. S., Riaño, J. D., Espinoza, A. B., Tovar, S. R., & Martínez, E. R. V. (2008). Progesterona en Microesferas para el Tratamiento en Infertilidad. Acta Médica Grupo Ángeles, 6(1), 8. http://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/actmed/am-2008/am081b.pdf

- ↑ Tobías, G. M., & Martínez, E. R. V. (2009). Técnica para Aplicación de Fármacos con Microesferas en Suspensión. Acta Médica Grupo Ángeles, 7(1), 13. http://www.medigraphic.com/pdfs/actmed/am-2009/am091b.pdf

- ↑ Lockwood G, Griesinger G, Cometti B (2014). "Subcutaneous progesterone versus vaginal progesterone gel for luteal phase support in in vitro fertilization: a noninferiority randomized controlled study". Fertil. Steril. 101 (1): 112–119.e3. doi:10.1016/j.fertnstert.2013.09.010. PMID 24140033.

- 1 2 3 Baker VL, Jones CA, Doody K, Foulk R, Yee B, Adamson GD, et al. (2014). "A randomized, controlled trial comparing the efficacy and safety of aqueous subcutaneous progesterone with vaginal progesterone for luteal phase support of in vitro fertilization". Hum. Reprod. 29 (10): 2212–20. doi:10.1093/humrep/deu194. PMC 4164149

. PMID 25100106.

. PMID 25100106. - ↑ Blackburn S (14 April 2014). Maternal, Fetal, & Neonatal Physiology. Elsevier Health Sciences. pp. 92–. ISBN 978-0-323-29296-2.

- ↑ Walker A (7 March 2008). The Menstrual Cycle. Routledge. pp. 49–. ISBN 978-1-134-71411-7.

- ↑ Ginsburg B (6 December 2012). Premenstrual Syndrome: Ethical and Legal Implications in a Biomedical Perspective. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 274–. ISBN 978-1-4684-5275-4.

- ↑ Gerald, Michael (2013). The Drug Book. New York, New York: Sterling Publishing. p. 186. ISBN 9781402782640.

- 1 2 Sauer MV (1 March 2013). Principles of Oocyte and Embryo Donation. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 7,118. ISBN 978-1-4471-2392-7.

- 1 2 Minkin MJ, Wright CV (2005). A Woman's Guide to Menopause & Perimenopause. Yale University Press. pp. 143–. ISBN 978-0-300-10435-6.

- ↑ Racowsky C, Schlegel PN, Fauser BC, Carrell D (7 June 2011). Biennial Review of Infertility. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 84–85. ISBN 978-1-4419-8456-2.

- ↑ http://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/www_bget?dr:D00066

- 1 2 3 4 https://www.drugs.com/international/progesterone.html

- ↑ J. Elks (14 November 2014). The Dictionary of Drugs: Chemical Data: Chemical Data, Structures and Bibliographies. Springer. pp. 1024–. ISBN 978-1-4757-2085-3.

- 1 2 3 Index Nominum 2000: International Drug Directory. Taylor & Francis. January 2000. pp. 880–. ISBN 978-3-88763-075-1.

- ↑ I.K. Morton; Judith M. Hall (31 October 1999). Concise Dictionary of Pharmacological Agents: Properties and Synonyms. Springer Science & Business Media. pp. 232–. ISBN 978-0-7514-0499-9.

- ↑ "Drugs@FDA: FDA Approved Drug Products" (HTML). United States Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ http://adisinsight.springer.com/drugs/800038089

- ↑ Pickar JH, Bon C, Amadio JM, Mirkin S, Bernick B (2015). "Pharmacokinetics of the first combination 17β-estradiol/progesterone capsule in clinical development for menopausal hormone therapy". Menopause. 22 (12): 1308–16. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000467. PMC 4666011

. PMID 25944519.

. PMID 25944519. - ↑ Kaunitz AM, Kaunitz JD (2015). "Compounded bioidentical hormone therapy: time for a reality check?". Menopause. 22 (9): 919–20. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000484. PMID 26035149.

- ↑ Pinkerton JV, Pickar JH (2016). "Update on medical and regulatory issues pertaining to compounded and FDA-approved drugs, including hormone therapy". Menopause. 23 (2): 215–23. doi:10.1097/GME.0000000000000523. PMC 4927324

. PMID 26418479.

. PMID 26418479. - ↑ Espinoza TR, Wright DW (2011). "The role of progesterone in traumatic brain injury". The Journal of Head Trauma Rehabilitation. 26 (6): 497–9. doi:10.1097/HTR.0b013e31823088fa. PMID 22088981.

- 1 2 Stein DG (September 2011). "Progesterone in the treatment of acute traumatic brain injury: a clinical perspective and update". Neuroscience. 191: 101–6. doi:10.1016/j.neuroscience.2011.04.013. PMID 21497181.

- ↑ Gibson CL, Gray LJ, Bath PM, Murphy SP (February 2008). "Progesterone for the treatment of experimental brain injury; a systematic review". Brain. 131 (Pt 2): 318–28. doi:10.1093/brain/awm183. PMID 17715141.

- ↑ Wright DW, Kellermann AL, Hertzberg VS, Clark PL, Frankel M, Goldstein FC, Salomone JP, Dent LL, Harris OA, Ander DS, Lowery DW, Patel MM, Denson DD, Gordon AB, Wald MM, Gupta S, Hoffman SW, Stein DG (April 2007). "ProTECT: a randomized clinical trial of progesterone for acute traumatic brain injury". Annals of Emergency Medicine. 49 (4): 391–402, 402.e1–2. doi:10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.07.932. PMID 17011666.

- ↑ Xiao G, Wei J, Yan W, Wang W, Lu Z (April 2008). "Improved outcomes from the administration of progesterone for patients with acute severe traumatic brain injury: a randomized controlled trial". Critical Care. 12 (2): R61. doi:10.1186/cc6887. PMC 2447617

. PMID 18447940.

. PMID 18447940. - ↑ Cekic M, Sayeed I, Stein DG (July 2009). "Combination treatment with progesterone and vitamin D hormone may be more effective than monotherapy for nervous system injury and disease". Frontiers in Neuroendocrinology. 30 (2): 158–72. doi:10.1016/j.yfrne.2009.04.002. PMC 3025702

. PMID 19394357.

. PMID 19394357. - ↑ Khaksari M, Soltani Z, Shahrokhi N, Moshtaghi G, Asadikaram G (January 2011). "The role of estrogen and progesterone, administered alone and in combination, in modulating cytokine concentration following traumatic brain injury". Canadian Journal of Physiology and Pharmacology. 89 (1): 31–40. doi:10.1139/y10-103. PMID 21186375.

- ↑ "Efficacy and Safety Study of Intravenous Progesterone in Patients With Severe Traumatic Brain Injury (SyNAPSe)". ClinicalTrials.gov. U.S. National Institutes of Health. Retrieved 2012-07-14.

- ↑ "SyNAPse: The Global phase 3 study of progesterone in severe traumatic brain injury". BHR Pharma, LLC.

- ↑ Sofuoglu M, Mitchell E, Mooney M (October 2009). "Progesterone effects on subjective and physiological responses to intravenous nicotine in male and female smokers". Human Psychopharmacology. 24 (7): 559–64. doi:10.1002/hup.1055. PMC 2785078

. PMID 19743227.

. PMID 19743227.