Heroin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Heroin: /ˈhɛroʊɪn/ |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | heroin |

| Dependence liability |

Physical: Very high Psychological: Very high |

| Addiction liability | Highly[2] |

| Routes of administration | Intravenous, inhalation, transmucosal, by mouth, intranasal, rectal, intramuscular, subcutaneous, intrathecal |

| ATC code | N07BC06 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | <35% (by mouth), 44–61% (inhaled)[3] |

| Protein binding | 0% (morphine metabolite 35%) |

| Metabolism | liver |

| Onset of action | Within minutes[4] |

| Biological half-life | 2–3 minutes[5] |

| Duration of action | 4 to 5 hours[6] |

| Excretion | 90% kidney as glucuronides, rest biliary |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| Synonyms | Diamorphine, Diacetylmorphine, Acetomorphine, (Dual) Acetylated morphine, Morphine diacetate |

| CAS Number |

561-27-3 |

| PubChem (CID) | 5462328 |

| DrugBank |

DB01452 |

| ChemSpider |

4575379 |

| UNII |

8H672SHT8E |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:27808 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL459324 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

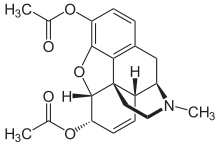

| Formula | C21H23NO5 |

| Molar mass | 369.41 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Heroin, also known as diamorphine among other names,[1] is an opioid typically used as a recreational drug for its euphoric effects.[2] Medically it is occasionally used as a pain medication and given to long-term users as a form of opioid replacement therapy alongside counseling.[7][8][9] Heroin is typically injected into a vein; however, can also be smoked or inhaled.[10][2] Onset of effects is usually rapid and lasts for a few hours.[2]

Common side effects include respiratory depression (decreased breathing) and about a quarter of those who use heroin become physically dependent. Other side effects can include abscesses, infected heart valves, blood borne infections, constipation, and pneumonia. After a history of long-term use, withdrawal symptoms can begin within hours of last use.[10] When given by injection into a vein, heroin has two to three times the effect as a similar dose of morphine.[2] It typically comes as a white or brown powder.[10]

Treatment of heroin addiction often includes behavioral therapy and medications. Medications used may include methadone or naltrexone. A heroin overdose may be treated with naloxone.[10] An estimated 33 million people currently use opiates or opioids such as heroin, which resulted in 122,000 deaths in 2015.[11][12] In the United States, heroin use has risen dramatically in the past ten years and about 1.6 percent of people have used heroin at some point in time.[10] Opioids are the most common cause of drug related deaths globally.[11]

Heroin was first made by C. R. Alder Wright in 1874 from morphine, a natural product of the opium poppy.[13] Internationally, heroin is controlled under Schedules I and IV of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs.[14] It is generally illegal to make, possess, or sell heroin without a license.[15] In 2015 Afghanistan produced about 66% of the world's opium.[11] Often heroin, which is illegally sold, is mixed with other substances such as sugar or strychnine.[2]

Uses

Recreational

The original trade name of heroin is typically used in non-medical settings. It is used as a recreational drug for the euphoria it induces. Anthropologist Michael Agar once described heroin as "the perfect whatever drug."[17] Tolerance develops quickly, and increased doses are needed in order to achieve the same effects. Its popularity with recreational drug users, compared to morphine, reportedly stems from its perceived different effects.[18] In particular, users report an intense rush, an acute transcendent state of euphoria, which occurs while diamorphine is being metabolized into 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM) and morphine in the brain. Some believe that heroin produces more euphoria than other opioids; one possible explanation is the presence of 6-monoacetylmorphine, a metabolite unique to heroin – although a more likely explanation is the rapidity of onset. While other opioids of recreational use produce only morphine, heroin also leaves 6-MAM, also a psycho-active metabolite. However, this perception is not supported by the results of clinical studies comparing the physiological and subjective effects of injected heroin and morphine in individuals formerly addicted to opioids; these subjects showed no preference for one drug over the other. Equipotent injected doses had comparable action courses, with no difference in subjects' self-rated feelings of euphoria, ambition, nervousness, relaxation, drowsiness, or sleepiness.[19]

Short-term addiction studies by the same researchers demonstrated that tolerance developed at a similar rate to both heroin and morphine. When compared to the opioids hydromorphone, fentanyl, oxycodone, and pethidine (meperidine), former addicts showed a strong preference for heroin and morphine, suggesting that heroin and morphine are particularly susceptible to abuse and addiction. Morphine and heroin were also much more likely to produce euphoria and other positive subjective effects when compared to these other opioids.[19]

Some researchers have attempted to explain heroin use and the culture that surrounds it through the use of sociological theories. In Righteous Dopefiend, Philippe Bourgois and Jeff Schonberg use anomie theory to explain why people begin using heroin. By analyzing a community in San Francisco, they demonstrated that heroin use was caused in part by internal and external factors such as violent homes and parental neglect. This lack of emotional, social, and financial support causes strain and influences individuals to engage in deviant acts, including heroin usage.[20] They further found that heroin users practiced "retreatism", a behavior first described by Howard Abadinsky, in which those suffering from such strain reject society's goals and institutionalized means of achieving them.[21]

Medical uses

In the United States heroin is not seen as medically useful.[2]

Under the generic name diamorphine, heroin is prescribed as a strong pain medication in the United Kingdom, where it is given via subcutaneous, intramuscular, intrathecal or intravenously. Its use includes treatment for acute pain, such as in severe physical trauma, myocardial infarction, post-surgical pain, and chronic pain, including end-stage cancer and other terminal illnesses. In other countries it is more common to use morphine or other strong opioids in these situations. In 2004 the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence produced guidance on the management of caesarian section, which recommended the use of intrathecal or epidural diamorphine for post-operative pain relief.[22]

Diamorphine continues to be widely used in palliative care in the UK, where it is commonly given by the subcutaneous route, often via a syringe driver, if patients cannot easily swallow morphine solution. The advantage of diamorphine over morphine is that diamorphine is more fat soluble and therefore more potent by injection, so smaller doses of it are needed for the same effect on pain. Both of these factors are advantageous if giving high doses of opioids via the subcutaneous route, which is often necessary in palliative care.

Maintenance therapy

A number of European countries including the United Kingdom allow the prescribing of heroin for heroin addiction.[23]

Diamorphine is also used as a maintenance drug to assist the treatment of opiate addiction, normally in long-term chronic intravenous (IV) heroin users. It is only prescribed following exhaustive efforts at treatment via other means. It is sometimes thought that heroin users can walk into a clinic and walk out with a prescription, but the process takes many weeks before a prescription for diamorphine is issued. Though this is somewhat controversial among proponents of a zero-tolerance drug policy, it has proven superior to methadone in improving the social and health situations of addicts.[24]

The UK Department of Health's Rolleston Committee Report[25] in 1926 established the British approach to diamorphine prescription to users, which was maintained for the next 40 years: dealers were prosecuted, but doctors could prescribe diamorphine to users when withdrawing from it would cause harm or severe distress to the patient. This "policing and prescribing" policy effectively controlled the perceived diamorphine problem in the UK until 1959 when the number of diamorphine addicts doubled every 16 months during the ten years from 1959 to 1968.[26] In 1964 the Brain Committee recommended that only selected approved doctors working at approved specialised centres be allowed to prescribe diamorphine and benzoylmethylecgonine (cocaine) to users. The law was made more restrictive in 1968. Beginning in the 1970s, the emphasis shifted to abstinence and the use of methadone; currently only a small number of users in the UK are prescribed diamorphine.[27]

In 1994 Switzerland began a trial diamorphine maintenance program for users that had failed multiple withdrawal programs. The aim of this program was to maintain the health of the user by avoiding medical problems stemming from the illicit use of diamorphine. The first trial in 1994 involved 340 users, although enrollment was later expanded to 1000 based on the apparent success of the program.

The trials proved diamorphine maintenance to be superior to other forms of treatment in improving the social and health situation for this group of patients.[28] It has also been shown to save money, despite high treatment expenses, as it significantly reduces costs incurred by trials, incarceration, health interventions and delinquency.[29] Patients appear twice daily at a treatment center, where they inject their dose of diamorphine under the supervision of medical staff. They are required to contribute about 450 Swiss francs per month to the treatment costs.[30] A national referendum in November 2008 showed 68% of voters supported the plan,[31] introducing diamorphine prescription into federal law. The previous trials were based on time-limited executive ordinances. The success of the Swiss trials led German, Dutch,[32] and Canadian[33] cities to try out their own diamorphine prescription programs.[34] Some Australian cities (such as Sydney) have instituted legal diamorphine supervised injecting centers, in line with other wider harm minimization programs.

Since January 2009, Denmark has prescribed diamorphine to a few addicts that have tried methadone and subutex without success.[35] Beginning in February 2010, addicts in Copenhagen and Odense became eligible to receive free diamorphine. Later in 2010 other cities including Århus and Esbjerg joined the scheme. It was supposed that around 230 addicts would be able to receive free diamorphine.[36] However, Danish addicts would only be able to inject heroin according to the policy set by Danish National Board of Health.[37] Of the estimated 1500 drug users who did not benefit from the then-current oral substitution treatment, approximately 900 would not be in the target group for treatment with injectable diamorphine, either because of "massive multiple drug abuse of non-opioids" or "not wanting treatment with injectable diamorphine".[38]

In July 2009 the German Bundestag passed a law allowing diamorphine prescription as a standard treatment for addicts; a large-scale trial of diamorphine prescription had been authorized in that country in 2002.[39]

On August 26 2016 Health Canada issued regulations amending prior regulations it had issued under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act; the "New Classes of Practitioners Regulations", the "Narcotic Control Regulations", and the "Food and Drug Regulations", to allow doctors to prescribe diamorphine to people who have a severe opioid addiction who haven't responded to other treatments.[40][41] The prescription heroin can be accessed by doctors through Health Canada's Special Access Programme (SAP) for "emergency access to drugs for patients with serious or life-threatening conditions when conventional treatments have failed, are unsuitable, or are unavailable."[40]

Routes of administration

| Recreational uses:

Medicinal uses: |

| Contraindications: |

| Central nervous system:

Neurological: Psychological: Cardiovascular & Respiratory: Gastrointestinal:

Musculoskeletal: Skin:

Miscellaneous:

Diamorphine ampoules for medicinal use |

The onset of heroin's effects depends upon the route of administration. Studies have shown that the subjective pleasure of drug use (the reinforcing component of addiction) is proportional to the rate at which the blood level of the drug increases.[42] Intravenous injection is the fastest route of drug administration, causing blood concentrations to rise the most quickly, followed by smoking, suppository (anal or vaginal insertion), insufflation (snorting), and ingestion (swallowing).

Ingestion does not produce a rush as forerunner to the high experienced with the use of heroin, which is most pronounced with intravenous use. While the onset of the rush induced by injection can occur in as little as a few seconds, the oral route of administration requires approximately half an hour before the high sets in. Thus, with both higher the dosage of heroin used and faster the route of administration used, the higher potential risk for psychological addiction.

Large doses of heroin can cause fatal respiratory depression, and the drug has been used for suicide or as a murder weapon. The serial killer Harold Shipman used diamorphine on his victims, and the subsequent Shipman Inquiry led to a tightening of the regulations surrounding the storage, prescribing and destruction of controlled drugs in the UK. John Bodkin Adams is also known to have used heroin as a murder weapon.

Because significant tolerance to respiratory depression develops quickly with continued use and is lost just as quickly during withdrawal, it is often difficult to determine whether a heroin lethal overdose was accidental, suicide or homicide. Examples include the overdose deaths of Sid Vicious, Janis Joplin, Tim Buckley, Hillel Slovak, Layne Staley, Bradley Nowell, Ted Binion, and River Phoenix.[43]

Chronic use of heroin and other opioids has been shown to be a potential cause of hyponatremia, resultant because of excess vasopressin secretion.

Oral

Oral use of heroin is less common than other methods of administration, mainly because there is little to no "rush", and the effects are less potent.[44] Heroin is entirely converted to morphine by means of first-pass metabolism, resulting in deacetylation when ingested. Heroin's oral bioavailability is both dose-dependent (as is morphine's) and significantly higher than oral use of morphine itself, reaching up to 64.2% for high doses and 45.6% for low doses; opiate-naive users showed far less absorption of the drug at low doses, having bioavailabilities of only up to 22.9%. The maximum plasma concentration of morphine following oral administration of heroin was around twice as much as that of oral morphine.[45]

Injection

Injection, also known as "slamming", "banging", "shooting up", "digging" or "mainlining", is a popular method which carries relatively greater risks than other methods of administration. Heroin base (commonly found in Europe), when prepared for injection, will only dissolve in water when mixed with an acid (most commonly citric acid powder or lemon juice) and heated. Heroin in the east-coast United States is most commonly found in the hydrochloride salt form, requiring just water (and no heat) to dissolve. Users tend to initially inject in the easily accessible arm veins, but as these veins collapse over time, users resort to more dangerous areas of the body, such as the femoral vein in the groin. Users who have used this route of administration often develop a deep vein thrombosis. Intravenous users can use a various single dose range using a hypodermic needle. The dose of heroin used for recreational purposes is dependent on the frequency and level of use: thus a first-time user may use between 5 and 20 mg, while an established addict may require several hundred mg per day. As with the injection of any drug, if a group of users share a common needle without sterilization procedures, blood-borne diseases, such as HIV or hepatitis, can be transmitted. The use of a common dispenser for water for the use in the preparation of the injection, as well as the sharing of spoons and/or filters can also cause the spread of blood-borne diseases. Many countries now supply small sterile spoons and filters for single use in order to prevent the spread of disease.[46]

Smoking

Smoking heroin refers to vaporizing it to inhale the resulting fumes, not burning it to inhale the resulting smoke. It is commonly smoked in glass pipes made from glassblown Pyrex tubes and light bulbs. It can also be smoked off aluminium foil, which is heated underneath by a flame and the resulting smoke is inhaled through a tube of rolled up foil, This method is also known as "chasing the dragon" (whereas smoking methamphetamine is known as "chasing the white dragon").

Insufflation

Another popular route to intake heroin is insufflation (snorting), where a user crushes the heroin into a fine powder and then gently inhales it (sometimes with a straw or a rolled-up banknote, as with cocaine) into the nose, where heroin is absorbed through the soft tissue in the mucous membrane of the sinus cavity and straight into the bloodstream. This method of administration redirects first-pass metabolism, with a quicker onset and higher bioavailability than oral administration, though the duration of action is shortened. This method is sometimes preferred by users who do not want to prepare and administer heroin for injection or smoking, but still experience a fast onset. Snorting heroin becomes an often unwanted route, once a user begins to inject the drug. The user may still get high on the drug from snorting, and experience a nod, but will not get a rush. A "rush" is caused by a large amount of heroin entering the body at once. When the drug is taken in through the nose, the user does not get the rush because the drug is absorbed slowly rather than instantly.

Suppository

Little research has been focused on the suppository (anal insertion) or pessary (vaginal insertion) methods of administration, also known as "plugging". These methods of administration are commonly carried out using an oral syringe. Heroin can be dissolved and withdrawn into an oral syringe which may then be lubricated and inserted into the anus or vagina before the plunger is pushed. The rectum or the vaginal canal is where the majority of the drug would likely be taken up, through the membranes lining their walls.

Adverse effects

Like most opioids, unadulterated heroin does not cause many long-term complications other than dependence and constipation.[47] The purity of street heroin varies greatly. This variation has led to individuals inadvertently experiencing overdoses when the purity of the drug was higher than they expected.[48][49] Intravenous use of heroin (and any other substance) with needles and syringes or other related equipment may lead to:

- Contracting blood-borne pathogens such as HIV and hepatitis via the sharing of needles

- Contracting bacterial or fungal endocarditis and possibly venous sclerosis

- Abscesses

- Poisoning from contaminants added to "cut" or dilute heroin

- Decreased kidney function (nephropathy), although it is not currently known if this is because of adulterants or infectious diseases[50]

Many countries and local governments have begun funding programs that supply sterile needles to people who inject illegal drugs in an attempt to reduce these contingent risks, and especially the spread of blood-borne diseases. The Drug Policy Alliance reports that up to 75% of new AIDS cases among women and children are directly or indirectly a consequence of drug use by injection.[51] The United States federal government does not operate needle exchanges, although some state and local governments do support such programs.

Anthropologists Philippe Bourgois and Jeff Schonberg performed a decade of fieldwork among homeless heroin and cocaine addicts in San Francisco, published in 2009. They reported that the African-American addicts they observed were more inclined to "direct deposit" heroin into a vein, while "skin-popping" was a far more widespread practice: "By the midpoint of our fieldwork, most of the whites had given up searching for operable veins and skin-popped. They sank their needles perfunctorily, often through their clothing, into their fatty tissue." Bourgois and Schonberg describes how the cultural difference between the African-Americans and the whites leads to this contrasting behavior, and also points out that the two different ways to inject heroin comes with different health risks. Skin-popping more often results in abscesses, and direct injection more often leads to fatal overdose and also to hepatitis C and HIV infection.[20]

A small percentage of heroin smokers, and occasionally IV users, may develop symptoms of toxic leukoencephalopathy. The cause has yet to be identified, but one speculation is that the disorder is caused by an uncommon adulterant that is only active when heated.[52][53][54] Symptoms include slurred speech and difficulty walking.

Cocaine is sometimes used in combination with heroin, and is referred to as a speedball when injected or moonrocks when smoked together. Cocaine acts as a stimulant, whereas heroin acts as a depressant. Coadministration provides an intense rush of euphoria with a high that combines both effects of the drugs, while excluding the negative effects, such as anxiety and sedation. The effects of cocaine wear off far more quickly than heroin, so if an overdose of heroin was used to compensate for cocaine, the end result is fatal respiratory depression.

-

Preparing heroin for injection

-

Modified syringe for suppository administration

-

One stamp of heroin

-

Chunky "No.3" heroin

Withdrawal

The withdrawal syndrome from heroin (the so-called "cold turkey") may begin within 6–24 hours of discontinuation of the drug; however, this time frame can fluctuate with the degree of tolerance as well as the amount of the last consumed dose. Symptoms may include:[55] sweating, malaise, anxiety, depression, akathisia, priapism, extra sensitivity of the genitals in females, general feeling of heaviness, excessive yawning or sneezing, tears, rhinorrhea, sleep difficulties (insomnia), cold sweats, chills, severe muscle and bone aches, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, cramps, watery eyes,[56] fever and cramp-like pains and involuntary spasms in the limbs (thought to be an origin of the term "kicking the habit"[57]).

Overdose

Heroin overdose is usually treated with an opioid antagonist, such as naloxone (Narcan), or naltrexone. This reverses the effects of heroin and other opioids and causes an immediate return of consciousness but may result in withdrawal symptoms. The half-life of naloxone is shorter than most opioids, so that it has to be administered multiple times until the opioid has been metabolized by the body.

Depending on drug interactions and numerous other factors, death from overdose can take anywhere from several minutes to several hours. Death usually occurs due to lack of oxygen resulting from the lack of breathing caused by the opioid. Heroin overdoses can occur because of an unexpected increase in the dose or purity or because of diminished opioid tolerance. However, many fatalities reported as overdoses are probably caused by interactions with other depressant drugs such as alcohol or benzodiazepines.[58] It should also be noted that since heroin can cause nausea and vomiting, a significant number of deaths attributed to heroin overdose are caused by aspiration of vomit by an unconscious person. Some sources quote the median lethal dose (for an average 75 kg opiate-naive individual) as being between 75 and 600 mg.[59][60] Illicit heroin is of widely varying and unpredictable purity. This means that the user may prepare what they consider to be a moderate dose while actually taking far more than intended. Also, tolerance typically decreases after a period of abstinence. If this occurs and the user takes a dose comparable to their previous use, the user may experience drug effects that are much greater than expected, potentially resulting in an overdose. It has been speculated that an unknown portion of heroin-related deaths are the result of an overdose or allergic reaction to quinine, which may sometimes be used as a cutting agent.[61]

Pharmacology

When taken orally, heroin undergoes extensive first-pass metabolism via deacetylation, making it a prodrug for the systemic delivery of morphine.[62] When the drug is injected, however, it avoids this first-pass effect, very rapidly crossing the blood–brain barrier because of the presence of the acetyl groups, which render it much more fat soluble than morphine itself.[63] Once in the brain, it then is deacetylated variously into the inactive 3-monoacetylmorphine and the active 6-monoacetylmorphine (6-MAM), and then to morphine, which bind to μ-opioid receptors, resulting in the drug's euphoric, analgesic (pain relief), and anxiolytic (anti-anxiety) effects; heroin itself exhibits relatively low affinity for the μ receptor.[64] Unlike hydromorphone and oxymorphone, however, administered intravenously, heroin creates a larger histamine release, similar to morphine, resulting in the feeling of a greater subjective "body high" to some, but also instances of pruritus (itching) when they first start using.[65]

Both morphine and 6-MAM are μ-opioid agonists that bind to receptors present throughout the brain, spinal cord, and gut of all mammals. The μ-opioid receptor also binds endogenous opioid peptides such as β-endorphin, Leu-enkephalin, and Met-enkephalin. Repeated use of heroin results in a number of physiological changes, including an increase in the production of μ-opioid receptors (upregulation). These physiological alterations lead to tolerance and dependence, so that stopping heroin use results in uncomfortable symptoms including pain, anxiety, muscle spasms, and insomnia called the opioid withdrawal syndrome. Depending on usage it has an onset 4–24 hours after the last dose of heroin. Morphine also binds to δ- and κ-opioid receptors.

There is also evidence that 6-MAM binds to a subtype of μ-opioid receptors that are also activated by the morphine metabolite morphine-6β-glucuronide but not morphine itself.[66] The third subtype of third opioid type is the mu-3 receptor, which may be a commonality to other six-position monoesters of morphine. The contribution of these receptors to the overall pharmacology of heroin remains unknown.

A subclass of morphine derivatives, namely the 3,6 esters of morphine, with similar effects and uses, includes the clinically used strong analgesics nicomorphine (Vilan), and dipropanoylmorphine; there is also the latter's dihydromorphine analogue, diacetyldihydromorphine (Paralaudin). Two other 3,6 diesters of morphine invented in 1874–75 along with diamorphine, dibenzoylmorphine and acetylpropionylmorphine, were made as substitutes after it was outlawed in 1925 and, therefore, sold as the first "designer drugs" until they were outlawed by the League of Nations in 1930.

Chemistry

Detection in body fluids

The major metabolites of diamorphine, 6-MAM, morphine, morphine-3-glucuronide and morphine-6-glucuronide, may be quantitated in blood, plasma or urine to monitor for abuse, confirm a diagnosis of poisoning or assist in a medicolegal death investigation. Most commercial opiate screening tests cross-react appreciably with these metabolites, as well as with other biotransformation products likely to be present following usage of street-grade diamorphine such as 6-acetylcodeine and codeine. However, chromatographic techniques can easily distinguish and measure each of these substances. When interpreting the results of a test, it is important to consider the diamorphine usage history of the individual, since a chronic user can develop tolerance to doses that would incapacitate an opiate-naive individual, and the chronic user often has high baseline values of these metabolites in his system. Furthermore, some testing procedures employ a hydrolysis step before quantitation that converts many of the metabolic products to morphine, yielding a result that may be 2 times larger than with a method that examines each product individually.[67]

History

The opium poppy was cultivated in lower Mesopotamia as long ago as 3400 BCE.[68] The chemical analysis of opium in the 19th century revealed that most of its activity could be ascribed to two alkaloids, codeine and morphine.

Diamorphine was first synthesized in 1874 by C. R. Alder Wright, an English chemist working at St. Mary's Hospital Medical School in London. He had been experimenting with combining morphine with various acids. He boiled anhydrous morphine alkaloid with acetic anhydride for several hours and produced a more potent, acetylated form of morphine, now called diacetylmorphine or morphine diacetate. The compound was sent to F. M. Pierce of Owens College in Manchester for analysis. Pierce told Wright:

Doses ... were subcutaneously injected into young dogs and rabbits ... with the following general results ... great prostration, fear, and sleepiness speedily following the administration, the eyes being sensitive, and pupils constrict, considerable salivation being produced in dogs, and slight tendency to vomiting in some cases, but no actual emesis. Respiration was at first quickened, but subsequently reduced, and the heart's action was diminished, and rendered irregular. Marked want of coordinating power over the muscular movements, and loss of power in the pelvis and hind limbs, together with a diminution of temperature in the rectum of about 4°.[69]

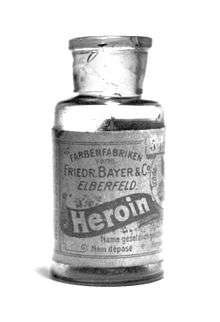

Wright's invention did not lead to any further developments, and diamorphine became popular only after it was independently re-synthesized 23 years later by another chemist, Felix Hoffmann.[70] Hoffmann, working at Bayer pharmaceutical company in Elberfeld, Germany, was instructed by his supervisor Heinrich Dreser to acetylate morphine with the objective of producing codeine, a constituent of the opium poppy, pharmacologically similar to morphine but less potent and less addictive. Instead, the experiment produced an acetylated form of morphine one and a half to two times more potent than morphine itself. The head of Bayer's research department reputedly coined the drug's new name, "heroin," based on the German heroisch, which means "heroic, strong" (from the ancient Greek word "heros, ήρως"). Bayer scientists were not the first to make heroin, but their scientists discovered ways to make it, and Bayer led commercialization of heroin.[71]

From 1898 through to 1910, diamorphine was marketed under the trademark name Heroin as a non-addictive morphine substitute and cough suppressant.[72] In the 11th edition of Encyclopædia Britannica (1910), the article on morphine states: "In the cough of phthisis minute doses [of morphine] are of service, but in this particular disease morphine is frequently better replaced by codeine or by heroin, which checks irritable coughs without the narcotism following upon the administration of morphine."

In the U.S., the Harrison Narcotics Tax Act was passed in 1914 to control the sale and distribution of diacetylmorphine and other opioids, which allowed the drug to be prescribed and sold for medical purposes. In 1924, the United States Congress banned its sale, importation, or manufacture. It is now a Schedule I substance, which makes it illegal for non-medical use in signatory nations of the Single Convention on Narcotic Drugs treaty, including the United States.

The Health Committee of the League of Nations banned diacetylmorphine in 1925, although it took more than three years for this to be implemented. In the meantime, the first designer drugs, viz. 3,6 diesters and 6 monoesters of morphine and acetylated analogues of closely related drugs like hydromorphone and dihydromorphine, were produced in massive quantities to fill the worldwide demand for diacetylmorphine—this continued until 1930 when the Committee banned diacetylmorphine analogues with no therapeutic advantage over drugs already in use, the first major legislation of this type.

Later, as with Aspirin, Bayer lost some of its trademark rights to heroin under the 1919 Treaty of Versailles following the German defeat in World War I.[73]

Name

In 1895, the German drug company Bayer marketed diacetylmorphine as an over-the-counter drug under the trademark name Heroin.[74] The name was derived from the Greek word heros because of its perceived "heroic" effects upon a user.[74] It was developed chiefly as a morphine substitute for cough suppressants that did not have morphine's addictive side-effects. Morphine at the time was a popular recreational drug, and Bayer wished to find a similar but non-addictive substitute to market. However, contrary to Bayer's advertising as a "non-addictive morphine substitute," heroin would soon have one of the highest rates of addiction among its users.[75]

"Diamorphine" is the Recommended International Nonproprietary Name and British Approved Name.[76][1] Other synonyms for heroin include: diacetylmorphine, and morphine diacetate. Heroin is also known by many street names including dope, H, smack, junk, horse, and brown, among others.[77]

Society and culture

Legal status

Asia

In Hong Kong, diamorphine is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It is available by prescription. Anyone supplying diamorphine without a valid prescription can be fined $10,000 (HKD). The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing diamorphine is a $50,000 (HKD) fine and life imprisonment. Possession of diamorphine without a license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $10,000 (HKD) fine and/or 7 years of jail time.[78]

Europe

In the Netherlands, diamorphine is a List I drug of the Opium Law. It is available for prescription under tight regulation exclusively to long-term addicts for whom methadone maintenance treatment has failed. It cannot be used to treat severe pain or other illnesses.[79]

In the United Kingdom, diamorphine is available by prescription, though it is a restricted Class A drug. According to the 50th edition of the British National Formulary (BNF), diamorphine hydrochloride may be used in the treatment of acute pain, myocardial infarction, acute pulmonary oedema, and chronic pain. The treatment of chronic non-malignant pain must be supervised by a specialist. The BNF notes that all opioid analgesics cause dependence and tolerance but that this is "no deterrent in the control of pain in terminal illness". When used in the palliative care of cancer patients, diamorphine is often injected using a syringe driver.[80]

It is controlled in the UK by the Misuse of Drugs Act 1971. In the UK it is a class A controlled drug and as such is subject to guidelines surrounding its storage, administration and destruction. Possession of diamorphine without a prescription is an arrestable offence. When diamorphine is prescribed in a hospital or similar environment, its administration must be supervised by two people who must then complete and sign a controlled drugs register (CD register) detailing the patient's name, amount, time, date and route of administration. In the case of a physician administering diamorphine, then he/she may administer the drug alone, however the rule requiring two registered practitioners, such as a nurse, midwife or another physician to sign the CD register still applies. The use of a witness when administering diamorphine is to avoid the possibility of the drug being diverted onto the black market.

For safety reasons, many UK National Health Service hospitals only permit the administration of intravenous diamorphine in designated areas. In practice this usually means a critical care unit, an accident and emergency department, operating theatres by an anaesthetist or nurse anaesthetist or other such areas where close monitoring and support from senior staff is immediately available. However, administration by other routes is permitted in other areas of the hospital. This includes subcutaneous, intramuscular, intravenously as part of a patient controlled analgesia setup, and as an already established epidural infusion pump. Subcutaneous infusion, along with subcutaneous and intramuscular injection (bolus administration), is often used in the patient's own home, in order to treat severe pain in terminal illness.

Australia

In Australia diamorphine is listed as a schedule 9 prohibited substance under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[81] A schedule 9 drug is outlined in the Poisons Act 1964 as "Substances which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of the CEO." [82]

North America

In Canada, diamorphine is a controlled substance[83] under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA).[84] Any person seeking or obtaining diamorphine without disclosing authorization 30 days before obtaining another prescription from a practitioner is guilty of an indictable offense and subject to imprisonment for a term not exceeding seven years. Possession of diamorphine for the purpose of trafficking is an indictable offense and subject to imprisonment for life.

In the United States, diamorphine is a Schedule I drug according to the Controlled Substances Act of 1970, making it illegal to possess without a DEA license.[85] Possession of more than 100 grams of diamorphine or a mixture containing diamorphine is punishable with a minimum mandatory sentence of 5 years of imprisonment in a federal prison.

Economics

Production

Diamorphine is produced from acetylation of morphine derived from natural opium sources. Numerous mechanical and chemical means are used to purify the final product. The final products have a different appearance depending on purity and have different names.[86]

Heroin grades

Heroin purity has been classified into four grades. No.4 is the purest form – white powder (salt) to be easily dissolved and injected. No.3 is "brown sugar" for smoking (base). No.1 and No.2 are unprocessed raw heroin (salt or base).[87]

Trafficking and production

Traffic is heavy worldwide, with the biggest producer being Afghanistan. According to a U.N. sponsored survey,[88] in 2004, Afghanistan accounted for production of 87 percent of the world's diamorphine.[89] Afghan opium kills around 100,000 people annually.[90]

In 2003 The Independent reported:[91][92]

... The cultivation of opium [in Afghanistan] reached its peak in 1999, when 350 square miles (910 km2) of poppies were sown ... The following year the Taliban banned poppy cultivation, ... a move which cut production by 94 percent ... By 2001 only 30 square miles (78 km2) of land were in use for growing opium poppies. A year later, after American and British troops had removed the Taliban and installed the interim government, the land under cultivation leapt back to 285 square miles (740 km2), with Afghanistan supplanting Burma to become the world's largest opium producer once more.

Opium production in that country has increased rapidly since, reaching an all-time high in 2006. War in Afghanistan once again appeared as a facilitator of the trade.[93] Some 3.3 million Afghans are involved in producing opium.[94]

At present, opium poppies are mostly grown in Afghanistan (224,000 hectares (550,000 acres)), and in Southeast Asia, especially in the region known as the Golden Triangle straddling Burma (57,600 hectares (142,000 acres)), Thailand, Vietnam, Laos (6,200 hectares (15,000 acres)) and Yunnan province in China. There is also cultivation of opium poppies in Pakistan (493 hectares (1,220 acres)), Mexico (12,000 hectares (30,000 acres)) and in Colombia (378 hectares (930 acres)).[95] According to the DEA, the majority of the heroin consumed in the United States comes from Mexico (50%) and Colombia (43-45%) via Mexican criminal cartels such as Sinaloa Cartel.[96] However, these statistics may be significantly unreliable, the DEA's 50/50 split between Colombia and Mexico is contradicted by the amount of hectares cultivated in each country and in 2014, the DEA claimed most of the heroin in the US came from Colombia.[97] As of 2015, the Sinaloa Cartel is the most active drug cartel involved in smuggling illicit drugs such as heroin into the United States and trafficking them throughout the United States.[98] According to the Royal Canadian Mounted Police, 90% of the heroin seized in Canada (where the origin was known) came from Afghanistan.[99] Pakistan is the destination and transit point for 40 percent of the opiates produced in Afghanistan, other destinations of Afghan opiates are Russia, Europe and Iran.[100][101]

Conviction for trafficking heroin carries the death penalty in most Southeast Asian, some East Asian and Middle Eastern countries (see Use of death penalty worldwide for details), among which Malaysia, Singapore and Thailand are the most strict. The penalty applies even to citizens of countries where the penalty is not in place, sometimes causing controversy when foreign visitors are arrested for trafficking, for example the arrest of nine Australians in Bali, the death sentence given to Nola Blake in Thailand in 1987, or the hanging of an Australian citizen Van Tuong Nguyen in Singapore.

Trafficking history

The origins of the present international illegal heroin trade can be traced back to laws passed in many countries in the early 1900s that closely regulated the production and sale of opium and its derivatives including heroin. At first, heroin flowed from countries where it was still legal into countries where it was no longer legal. By the mid-1920s, heroin production had been made illegal in many parts of the world. An illegal trade developed at that time between heroin labs in China (mostly in Shanghai and Tianjin) and other nations. The weakness of government in China and conditions of civil war enabled heroin production to take root there. Chinese triad gangs eventually came to play a major role in the illicit heroin trade. The French Connection route started in the 1930s.

Heroin trafficking was virtually eliminated in the U.S. during World War II because of temporary trade disruptions caused by the war. Japan's war with China had cut the normal distribution routes for heroin and the war had generally disrupted the movement of opium.

After World War II, the Mafia took advantage of the weakness of the postwar Italian government and set up heroin labs in Sicily. The Mafia took advantage of Sicily's location along the historic route opium took westward into Europe and the United States.[102]

Large-scale international heroin production effectively ended in China with the victory of the communists in the civil war in the late 1940s. The elimination of Chinese production happened at the same time that Sicily's role in the trade developed.

Although it remained legal in some countries until after World War II, health risks, addiction, and widespread recreational use led most western countries to declare heroin a controlled substance by the latter half of the 20th century.

In late 1960s and early 1970s, the CIA supported anti-Communist Chinese Nationalists settled near the Sino-Burmese border and Hmong tribesmen in Laos. This helped the development of the Golden Triangle opium production region, which supplied about one-third of heroin consumed in US after the 1973 American withdrawal from Vietnam. In 1999, Burma, the heartland of the Golden Triangle, was the second largest producer of heroin, after Afghanistan.[103]

The Soviet-Afghan war led to increased production in the Pakistani-Afghan border regions, as U.S.-backed mujaheddin militants raised money for arms from selling opium, contributing heavily to the modern Golden Crescent creation. By 1980, 60 percent of heroin sold in the U.S. originated in Afghanistan.[103] It increased international production of heroin at lower prices in the 1980s. The trade shifted away from Sicily in the late 1970s as various criminal organizations violently fought with each other over the trade. The fighting also led to a stepped-up government law enforcement presence in Sicily. Following the discovery at a Jordanian airport of a toner cartridge that had been modified into an improvised explosive device, the resultant increased level of airfreight scrutiny led to a major shortage (drought) of heroin from October 2010 until April 2011. This was reported in most of mainland Europe and the UK which led to a price increase of approximately 30 percent in the cost of street heroin and an increased demand for diverted methadone. The number of addicts seeking treatment also increased significantly during this period. Other heroin droughts (shortages) have been attributed to cartels restricting supply in order to force a price increase and also to a fungus that attacked the opium crop of 2009. Many people thought that the American government had introduced pathogens into the Afghanistan atmosphere in order to destroy the opium crop and thus starve insurgents of income.

On 13 March 2012, Haji Bagcho, with ties to the Taliban, was convicted by a U.S. District Court of conspiracy, distribution of heroin for importation into the United States and narco-terrorism.[104][105][106][107][108][108] Based on heroin production statistics[109] compiled by the United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime, in 2006, Bagcho's activities accounted for approximately 20 percent of the world's total production for that year.[105][106][107][108]

Street price

The European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction reports that the retail price of brown heroin varies from €14.5 per gram in Turkey to €110 per gram in Sweden, with most European countries reporting typical prices of €35–40 per gram. The price of white heroin is reported only by a few European countries and ranged between €27 and €110 per gram.[110]

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime claims in its 2008 World Drug Report that typical US retail prices are US$172 per gram.[111]

Harm reduction

Harm reduction is a public health philosophy that seeks to reduce the harms associated with the use of diamorphine. One aspect of harm reduction initiatives focuses on the behaviour of individual users. This includes promoting safer means of taking the drug, such as smoking, nasal use, oral or rectal insertion. This attempts to avoid the higher risks of overdose, infections and blood-borne viruses associated with injecting the drug. Other measures include using a small amount of the drug first to gauge the strength, and minimize the risks of overdose. For the same reason, poly drug use (the use of two or more drugs at the same time) is discouraged. Injecting diamorphine users are encouraged to use new needles, syringes, spoons/steri-cups and filters every time they inject and not share these with other users. Users are also encouraged to not use it on their own, as others can assist in the event of an overdose.

Governments that support a harm reduction approach usually fund needle and syringe exchange programs, which supply new needles and syringes on a confidential basis, as well as education on proper filtering before injection, safer injection techniques, safe disposal of used injecting gear and other equipment used when preparing diamorphine for injection may also be supplied including citric acid sachets/vitamin C sachets, steri-cups, filters, alcohol pre-injection swabs, sterile water ampules and tourniquets (to stop use of shoe laces or belts).

Another harm reduction measure employed for example in Europe, Canada and Australia are safe injection sites where users can inject diamorphine and cocaine under the supervision of medically trained staff. Safe injection sites are low threshold and allow social services to approach problem users that would otherwise be hard to reach.[113] In the UK the Criminal Justice System has a protocol in place that requires that any individual that is arrested and is suspected of having a substance misuse problem be offered the chance to enter a treatment program. This has had the effect of drastically reducing an area's crime rate as individuals arrested for theft in order to supply the funds for their drugs are no longer in the position of having to steal to purchase heroin because they have been placed onto a methadone program, quite often more quickly than would have been possible had they not been arrested. This aspect of harm reduction is seen as being beneficial to both the individual and the community at large, who are then protected from the possible theft of their goods.[114][115]

During the late 1980s and early 1990s, Swiss authorities ran the ZIPP-AIDS (Zurich Intervention Pilot Project), handing out free syringes in the officially tolerated drug scene in Platzspitz park.[116] In 1994, Zurich started a pilot project using prescription heroin in heroin-assisted treatment (HAT) which allowed users to obtain heroin and inject it under medical supervision.[117] The HAT program proved to be cost-beneficial to society and improve patients overall health and social stability[117] and has since been introduced in multiple European countries.[118]

Popular culture

Heroin is mentioned in hundreds of films. Sometimes the use or trafficking of the drug is the central theme of the film but many times it is almost incidental as part of a crime in a police drama, for example.

- 1957 film Monkey on My Back based on the book about his addiction by boxer Barney Ross.

- A Hatful of Rain, the 1957 film based on the 1955 play by Michael V. Gazzo about an addicted Korean War veteran.

- The 1959 play The Connection by Jack Gelber, and the 1961 film adaptation of it, concern a group of addicts, some of whom are jazz musicians, waiting for their dealer.

- The film The Panic in Needle Park starring Al Pacino and Kitty Winn is the story of a young woman who falls in love with a heroin addict in New York. It was one of Pacino's first roles.

- The film American Gangster is loosely based on real-life drug dealer Frank Lucas, who sold heroin. Lucas was portrayed by Denzel Washington.[119]

- The film Gia, based on a true story of model Gia Carangi, is about her addiction to and use of heroin and how it affected her.[120]

- The film Christiane F. – Wir Kinder vom Bahnhof Zoo (We the children of Bahnhof Zoo) is about heroin use and street culture in West Berlin in the 1970s, centering on a 13-year-old girl's decision to experiment with the drug.

- The film Trainspotting chronicles the exploits of a group of heroin addicts in Edinburgh, Scotland, during the late 1980s.

- The film Requiem for a Dream tells the story of four drug (mainly heroin) addicts who can only witness their disastrous habits spiral out of control into the darkest, ugliest and dirtiest sides of humanity.[121]

- In season three of the American television series 24, the show's protagonist Jack Bauer is seen battling a heroin addiction after having spent months undercover working with a drug lord family in Mexico.

- The film The Basketball Diaries follows protagonist Jim Carrol's addiction to heroin and getting off heroin. Leonardo DiCaprio portrayed Carrol.

- The film Pulp Fiction, featuring John Travolta as Vincent Vega, shows IV use of the drug, and Uma Thurman's character Mia Wallace overdoses.

- The television series Breaking Bad features Jane Margolis, Jesse Pinkman's girlfriend/landlady, who is in rehab for heroin usage, but gets back into using it and introduces Jesse to it, but later dies due to the combination of an overdose and Walter White's refusal to save her life.

- The film Rush (1991) starring Jennifer Jason Leigh, Jason Patric, Sam Elliott and Gregg Allman is a fictionalized depiction of a heroin-trade-based corruption scandal that wracked the Tyler, Texas, US Police Department in the late seventies; undercover detective characters played by Leigh and Patric inadvertently become heroin addicts in the process of attempting to gather evidence against the local drug dealer played by Allman.

Use of heroin by jazz musicians in particular was prevalent in the mid-twentieth century, including Billie Holiday, sax legends Charlie Parker and Art Pepper, guitarist Joe Pass and piano player/singer Ray Charles; a "staggering number of jazz musicians were addicts".[122] It was also a problem with many rock musicians, particularly from the late 1960s through the 1990s. Pete Doherty is also a self-confessed user of heroin.[123] Nirvana frontman Kurt Cobain's heroin addiction was well documented.[124] Pantera frontman, Phil Anselmo, turned to heroin while touring during the 1990s to cope with his back pain.[125]

Songs

Heroin is mentioned explicitly in a number of rock songs:

- "Mr Brownstone" by Guns N' Roses[126]

- "Cold Turkey" by John Lennon was about Lennon and Yoko Ono going cold turkey off of their heroin addictions.[127]

- "Heroin" by The Velvet Underground describes the usage of the drug.[128]

- "Ashes to Ashes, Davie Bowie's 1980 single included lines that refer to Major Tom as "... a junkie/strung out on heaven's high/hitting an all-time low."[129]

- Songs such as "Junkhead", "Godsmack", "Dirt" "Hate to Feel" and "Angry Chair" from the album Dirt, including many others from other albums, by grunge band Alice in Chains.[130]

- "People Who Died" by The Jim Carroll Band. Several people in the song died of heroin-related causes.[131]

Research

Researchers are attempting to reproduce the biosynthetic pathway that produces morphine in genetically engineered yeast.[132] In June 2015 the S-reticuline could be produced from sugar and R-reticuline could be converted to morphine, but the intermediate reaction could not be performed.[133]

See also

- Allegations of CIA drug trafficking

- The Politics of Heroin in Southeast Asia

- Cheese (recreational drug)

References

- 1 2 3 Rang HP, Ritter JM, Flower RJ, Henderson G (2014). Rang & Dale's Pharmacology (8th ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 515. ISBN 9780702054976. Retrieved 12 April 2016.

While 'diamorphine' is the recommended International Nonproprietary Name (rINN), this drug is widely known as heroin.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Heroin". Drugs.com. 18 May 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- ↑ Rook EJ, van Ree JM, van den Brink W, Hillebrand MJ, Huitema AD, Hendriks VM, Beijnen JH (2006). "Pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of high doses of pharmaceutically prepared heroin, by intravenous or by inhalation route in opioid-dependent patients". Basic Clin. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 98 (1): 86–96. doi:10.1111/j.1742-7843.2006.pto_233.x. PMID 16433897.

- ↑ Riviello, Ralph J. (2010). Manual of forensic emergency medicine : a guide for clinicians. Sudbury, Mass.: Jones and Bartlett Publishers. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-7637-4462-5.

- ↑ "Diamorphine Hydrochloride Injection 30 mg – Summary of Product Characteristics". electronic Medicines Compendium. ViroPharma Limited. 24 September 2013. Retrieved 30 March 2014.

- ↑ Field, John (2012). The Textbook of Emergency Cardiovascular Care and CPR. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. p. 447. ISBN 978-1-4698-0162-9.

- ↑ Friedrichsdorf, SJ; Postier, A (2014). "Management of breakthrough pain in children with cancer.". Journal of pain research. 7: 117–23. PMID 24639603.

- ↑ National Collaborating Centre for Cancer, (UK) (May 2012). "Opioids in Palliative Care: Safe and Effective Prescribing of Strong Opioids for Pain in Palliative Care of Adults". PMID 23285502.

- ↑ Uchtenhagen AA (March 2011). "Heroin maintenance treatment: from idea to research to practice.". Drug and Alcohol Review. 30 (2): 130–7. doi:10.1111/j.1465-3362.2010.00266.x. PMID 21375613.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "DrugFacts—Heroin". National Institute on Drug Abuse. October 2014. Retrieved 19 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Statistical tables". World Drug Report 2016 (pdf). Vienna, Austria. May 2016. p. xii,. ISBN 978-92-1-057862-2. Retrieved 1 August 2016.

- ↑ GBD 2015 Mortality and Causes of Death, Collaborators. (8 October 2016). "Global, regional, and national life expectancy, all-cause mortality, and cause-specific mortality for 249 causes of death, 1980-2015: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015.". Lancet (London, England). 388 (10053): 1459–1544. PMID 27733281.

- ↑ A Century of International Drug Control. United Nations Publications. 2010. p. 49. ISBN 9789211482454.

- ↑ "Yellow List: List of Narcotic Drugs Under International Control" (PDF). International Narcotics Control Board. December 2004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 May 2012. Retrieved 5 May 2006. Referring URL = http://www.incb.org/incb/yellow_list.html

- ↑ Lyman, Michael D. (2013). Drugs in Society: Causes, Concepts, and Control. Routledge. p. 45. ISBN 9780124071674.

- 1 2 "Office of National Drug Control Policy (ONDCP): Heroin Facts & Figures". Whitehousedrugpolicy.gov. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ Agar, Michael (2007). Dope Double Agent: The Naked Emperor on Drugs. Lulu.com. ISBN 1-4116-8103-7. Retrieved 22 October 2009.

What a great New York drug heroin was, I thought. Like any city, but more than most, New York is an information overload, a constant perceptual tornado that surrounds you most places you walk on the streets. Heroin is the audio-visual technology that helps manage that overload by dampening it in general and allowing a focus on some part of it that the human perceptual equipment was, in fact, designed to handle.

- ↑ "Time series modeling of heroin and morphine drug action". 1 January 2003. doi:10.1007/s00213-002-1271-3. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- 1 2 Martin WR, Fraser HF (September 1961). "A comparative study of physiological and subjective effects of heroin and morphine administered intravenously in postaddicts". Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 133: 388–99. PMID 13767429.

- 1 2 Bourgois, Philippe; Jeff Schonberg (2009). Righteous Dopefiend. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-25498-8. Retrieved 13 October 2009.

- ↑ Abadinsky, Howard (2007). Organized Crime. Wadsworth.

- ↑ "National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (2011) Caesarean section.NICE Guideline (CG132)". Retrieved 28 October 2015.

- ↑ Lintzeris, N (2009). "Prescription of heroin for the management of heroin dependence: current status.". CNS drugs. 23 (6): 463–76. PMID 19480466.

- ↑ Haasen C, Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Berger J, Krausz M, Naber D (2007). "Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: Randomised controlled trial". The British Journal of Psychiatry. 191: 55–62. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026112. PMID 17602126.

- ↑ "Rolleston Report". Departmental Commission on Morphine and Heroin Addiction, United Kingdom. 1926. Retrieved 28 January 2011.

- ↑ "Nils Bejerot: The Swedish Addiction Epidemic in global perspective". Archived from the original on 22 June 2007.

- ↑ Goldacre, Ben (1998). "Methadone and Heroin: An Exercise in Medical Scepticism". Retrieved 18 December 2006.

- ↑ Haasen C, Verthein U, Degkwitz P, Berger J, Krausz M, Naber D (July 2007). "Heroin-assisted treatment for opioid dependence: randomised controlled trial". Br J Psychiatry. 191: 55–62. doi:10.1192/bjp.bp.106.026112. PMID 17602126.

- ↑ "Heroin Assisted Treatment for Opiate Addicts – The Swiss Experience". Parl.gc.ca. 31 March 1995. Archived from the original on 20 January 2010. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ Nadelmann, Ethan (10 July 1995). "Switzerland's Heroin Experiment". Drug Policy Alliance. Archived from the original on 29 November 2004. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ "Swiss approve prescription heroin". BBC News Online. 30 November 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ↑ "Heroin prescription 'cuts costs'". BBC News. 5 June 2005. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ "About the study". North American Opiate Medication Initiative. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ Nordt C, Stohler R (2006). "Incidence of heroin use in Zurich, Switzerland: a treatment case register analysis". The Lancet. 367 (9525): 1830–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68804-1. PMID 16753485.

- ↑ "Danmark redo för skattebetalt heroin" (in Swedish). November 2008. Archived from the original on 3 December 2008. Retrieved 30 November 2008.

- ↑ "Gratis heroin klar til danske narkomaner" (in Danish). Information. January 2010. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ↑ "Heroin-behandling bliver kun i kanyler" (in Danish). Information. February 2009. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ↑ "Prescription of injectable heroin for drug users". Danish National Boad of Health. October 2007. Retrieved 14 February 2010.

- ↑ "Durchbruch für die Behandlung von Schwerstopiatabhängigen" [Breakthrough for the treatment of heavily addicted opiate users] (in German). Bundesministerium für Gesundheit (German ministry of health). 28 May 2009. Retrieved 28 April 2014.

- 1 2 "Regulations Amending Certain Regulations Made Under the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (Access to Diacetylmorphine for Emergency Treatment)". Canada Gazette Directorate. 7 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "Prescription heroin gets green light in Canada". CNN. 14 September 2016. Retrieved 19 September 2016.

- ↑ "Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics (JPET) | Onset of Action and Drug Reinforcement" (PDF). Retrieved 10 June 2012.

- ↑ Eason, Kevin; Naughton, Philippe (13 March 2012). "First murder charge over heroin mix that killed 400". London: Times Online. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ sepulfreak (8 July 2005). "Erowid Experience Vaults: Heroin – Catching the Waves – 41495". Erowid.org. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ Halbsguth U, Rentsch KM, Eich-Höchli D, Diterich I, Fattinger K (2008). "Oral diacetylmorphine (heroin) yields greater morphine bioavailability than oral morphine: Bioavailability related to dosage and prior opioid exposure". British Journal of Clinical Pharmacology. 66 (6): 781–791. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2008.03286.x. PMC 2675771

. PMID 18945270.

. PMID 18945270. - ↑ http://www.idaat.org/files/documents_file-4.pdf

- ↑ Merck Manual of Home Health Handbook – 2nd edition, 2003, p. 2097

- ↑ Seelye, Katharine Q. (2016-03-25). "Heroin Epidemic Is Yielding to a Deadlier Cousin: Fentanyl". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

- ↑ Bell, Bethany (26 June 2012). "BBC News – Afghan opium crop failure 'led to UK heroin shortage'". Bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 3 November 2012.

- ↑ Dettmeyer RB, Preuss J, Wollersen H, Madea B (2005). "Heroin-associated nephropathy". Expert Opinion on Drug Safety. 4 (1): 19–28. doi:10.1517/14740338.4.1.19. PMID 15709895.

- ↑ "DRUG POLICY AND HEALTH IN UKRAINE" (PDF). drugpolicy.org. 24 April 2002. pp. 6–7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 July 2004. Retrieved 17 May 2016.

Problems with reliability in reporting can be found in the disparity of the data when comparing government data with reports from the European Center for Epidemiological Monitoring of AIDS (Euro AIDS). Euro AIDS data states that in 1998 more than 75% of new HIV cases originated from the intravenous drug use. UNAIDS also reports that more than 75% of new HIV cases originate from intravenous drug users. The data sources concur that intravenous drug users are the highest risk group for the spread of AIDS in Ukraine.

- ↑ Hill MD, Cooper PW, Perry JR (January 2000). "Chasing the dragon—neurological toxicity associated with inhalation of heroin vapour: case report". CMAJ. 162 (2): 236–8. PMC 1232277

. PMID 10674060.

. PMID 10674060. - ↑ Halloran O, Ifthikharuddin S, Samkoff L (2005). "Leukoencephalopathy from "chasing the dragon"". Neurology. 64 (10): 1755. doi:10.1212/01.WNL.0000149907.63410.DA. PMID 15911804.

- ↑ Offiah C, Hall E (2008). "Heroin-induced leukoencephalopathy: characterization using MRI, diffusion-weighted imaging, and MR spectroscopy". Clinical Radiology. 63 (2): 146–52. doi:10.1016/j.crad.2007.07.021. PMID 18194689.

- ↑ "Narcotic Drug Withdrawal". Discovery Place. Retrieved 18 April 2014.

- ↑ Myaddiction (16 May 2012). "Heroin Withdrawal Symptoms". MyAddiction. Retrieved 16 May 2012.

- ↑ Stephens, Richard (1991). The Street Addict Role: A Theory of Heroin Addiction. SUNY Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-7914-0619-9.

- ↑ Darke S, Zador D (1996). "Fatal heroin 'overdose': a review". Addiction. 91 (12): 1765–1772. doi:10.1046/j.1360-0443.1996.911217652.x. PMID 8997759.

- ↑ "Toxic Substances in water". Lincoln.pps.k12.or.us. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ Breecher, Edward. "The Consumers Union Report on Licit and Illicit Drugs".

- ↑ The "heroin overdose" mystery and other occupational hazards of addiction, Schaffer Library of Drug Policy

- ↑ Sawynok J (January 1986). "The therapeutic use of heroin: a review of the pharmacological literature". Can. J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 64 (1): 1–6. doi:10.1139/y86-001. PMID 2420426.

- ↑ Klous MG, Van den Brink W, Van Ree JM, Beijnen JH (2005). "Development of pharmaceutical heroin preparations for medical co-prescription to opioid dependent patients". Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 80 (3): 283–95. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.04.008. PMID 15916865.

- ↑ Inturrisi CE, Schultz M, Shin S, Umans JG, Angel L, Simon EJ (1983). "Evidence from opiate binding studies that heroin acts through its metabolites". Life Sciences. 33: 773–6. doi:10.1016/0024-3205(83)90616-1. PMID 6319928.

- ↑ Histamine release by morphine and diamorphine in man. & Cutaneous Complications of Intravenous Drug Abuse

- ↑ Brown GP, Yang K, King MA, Rossi GC, Leventhal L, Chang A, Pasternak GW (1997). "3-Methoxynaltrexone, a selective heroin/morphine-6β-glucuronide antagonist". FEBS Letters. 412 (1): 35–8. doi:10.1016/S0014-5793(97)00710-2. PMID 9257684.

- ↑ Baselt, R. (2011). Disposition of Toxic Drugs and Chemicals in Man (9th ed.). Seal Beach, CA: Biomedical Publications. pp. 793–7. ISBN 978-0-9626523-8-7.

- ↑ "Opium Throughout History". PBS Frontline. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ Wright, C.R.A. (12 August 2003). "On the Action of Organic Acids and their Anhydrides on the Natural Alkaloids". Archived from the original on 6 June 2004. Note: this is an annotated excerpt of Wright, C.R.A. (1874). "On the Action of Organic Acids and their Anhydrides on the Natural Alkaloids". Journal of the Chemical Society. 27: 1031–1043. doi:10.1039/js8742701031.

- ↑ "Felix Hoffmann". Chemical Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ Jim Edwards for Business Insider. 17 November 2011 Yes, Bayer Promoted Heroin for Children – Here Are The Ads That Prove It

- ↑ Deborah Moore for the TimesUnion. 24 August 2014 Heroin: A brief history of unintended consequences

- ↑ "Treaty of Versailles, Part X, Section IV, Article 298". 28 June 1919. pp. Annex, Paragraph 5. Retrieved 25 October 2008.

- 1 2 "Online Etymology Dictionary". Etymonline.com. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ "The Most Addictive Drugs". Archived from the original on 13 February 2010.

- ↑ Rang HP, Dale MM, Flower RJ, Henderson G (2011). Rang & Dale's pharmacology (7th ed.). Edinburgh, UK: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-7020-3471-8.

- ↑ "Nicknames and Street Names for Heroin". Thecyn.com. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ "HEROIN, THE POPPY". Addiction Recovery Expose. Randolph Online Solutions Inc. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "Heroin". Mahalo.com. Mahalo.com Incorporated. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "Heroin". NACADA. NACADA. Archived from the original on 3 December 2012. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534

- ↑ Poisons Act 1964 http://www.slp.wa.gov.au/pco/prod/FileStore.nsf/Documents/MRDocument:26063P/$FILE/Poisons%20Act%201964%20-%20%5B09-f0-04%5D.pdf?OpenElement

- ↑ Ubelacker, Sheryl (12 March 2012). "Medically prescribed heroin more cost-effective than methadone, study suggests". thestar.com. The Toronto Star. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ "Heroin Legal Status". Vaults of Erowid. Erowid.org. Retrieved 27 May 2012.

- ↑ 21 CFR 1308.11 (CSA Sched I) with changes through 77 FR 64032 (18 October 2012)

- ↑ "Documentation of a heroin manufacturing process in Afghanistan. BULLETIN ON NARCOTICS, Volume LVII, Nos. 1 and 2, 2005" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 20 October 2010.

- ↑ "Heroin—Illicit Drug Report" (PDF). Government of Australia. 2004. Retrieved 31 March 2014.

- ↑ "Afghanistan opium survey – 2004" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ McGirk, Tim (2 August 2004). "Terrorism's Harvest: How al-Qaeda is tapping into the opium trade to finance its operations and destabilize Afghanistan". Time Magazine Asia. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ "World failing to dent heroin trade, U.N. warns". Cnn.com. 21 October 2009. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ Andy McSmith and Phil Reeves. "Afghanistan regains its Title as World's biggest Heroin Dealer" in The Independent, 22 June 2003

- ↑ North, Andrew (10 February 2004). "The drugs threat to Afghanistan". BBC. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- ↑ Gall, Carolotta (3 September 2006). "Opium Harvest at Record Level in Afghanistan". New York Times – Asia Pacific. Retrieved 22 October 2006.

- ↑ Walsh, Declan (30 August 2007). "UN horrified by surge in opium trade in Helmand". London: Guardian. Retrieved 20 July 2012.

- ↑ Government of Colombia (July 2015). "Coca cultivation survey" (PDF). Report. United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC). p. 67. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ 50% of the Heroin consumed in the United States is produced in Mexico, The Yucatan Times, November 26, 2014

- ↑ Yagoub, Mimi (26 May 2016). "Sinaloa Cartel's Takeover of US Heroin Market Questionable". Website. InSight Crime. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ "2015 National Drug Threat Assessment Summary" (PDF). Drug Enforcement Administration. United States Department of Justice: Drug Enforcement Administration. October 2015. pp. 1–2. Retrieved 10 April 2016.

Mexican TCOs pose the greatest criminal drug threat to the United States; no other group is currently positioned to challenge them. These Mexican poly-drug organizations traffic heroin, methamphetamine, cocaine, and marijuana throughout the United States, using established transportation routes and distribution networks. ... While all of these Mexican TCOs transport wholesale quantities of illicit drugs into the United States, the Sinaloa Cartel appears to be the most active supplier. The Sinaloa Cartel leverages its expansive resources and dominance in Mexico to facilitate the smuggling and transportation of drugs throughout the United States.

- ↑ Berthiaume, Lee (20 November 2014). "U.S. raises alarm over Afghan heroin flowing through Canada". Newspaper. Ottawa Citizen. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ Editorial Board (26 October 2014). "Afghanistan's Unending Addiction". Newspaper. The New York Times. Retrieved 28 May 2016.

- ↑ "Country Profile: Pakistan". United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 5 January 2015.

- ↑ Eric C. Schneider, Smack: Heroin and the American City, University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008, chapter one

- 1 2 "War Views: Afghan heroin trade will live on.". Richard Davenport-Hines. BBC. October 2001. Retrieved 30 October 2008.

- ↑ "Haji Bagcho Sentenced To Life in Prison on Narco-Terrorism, Drug Trafficking Charges – Funded Taliban, Responsible for Almost 20 Percent of World's Heroin Production, More Than a Quarter-Billion in Drug Proceeds, Property Forfeited". The Aiken Leader. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Haji Bagcho Convicted by Federal Jury in Washington, D.C., on Drug Trafficking and Narco-terrorism Charges – Afghan National Trafficked More Than 123,000 Kilograms of Heroin in 2006". US Department of Justice. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- 1 2 "Haji Bagcho Sentenced to Life in Prison on Trafficking/Narco-Terrorism Charges". Surfky News. Archived from the original on 16 January 2014. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- 1 2 Foster, Zachary. "Haji Bagcho, One of World's Largest Heroin Traffickers, Convicted on Drug Trafficking, Narco-Terrorism Charges". War on Terrorism Online. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- 1 2 3 TUCKER, ERIC (12 June 2012). "Afghan heroin trafficker gets life in US prison". Associated Press. Retrieved 7 June 2012.

- ↑ "2007 WORLD DRUG REPORT" (PDF). United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime. Retrieved 26 July 2012.

- ↑ European Monitoring Centre for Drugs and Drug Addiction (2008). Annual report: the state of the drugs problem in Europe (PDF). Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities. p. 70. ISBN 978-92-9168-324-6.

- ↑ United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (2008). World drug report (PDF). United Nations Publications. p. 49. ISBN 978-92-1-148229-4.

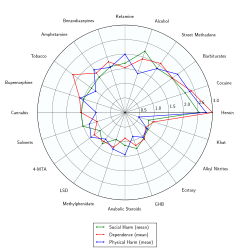

- ↑ Nutt, D.; King, L. A.; Saulsbury, W.; Blakemore, C. (2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse". The Lancet. 369 (9566): 1047–1053. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(07)60464-4. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ Kimber J, Dolan K, Wodak A (2005). "Survey of drug consumption rooms: service delivery and perceived public health and amenity impact". Drug and Alcohol Review. 24 (1): 21–4. doi:10.1080/09595230500125047. PMID 16191717.

- ↑ http://www.idaat.org/files/newsletters_file-8.pdf

- ↑ Lancashire Constabulary-Harm Reduction in the Community page 7

- ↑ "NCJRS Abstract - National Criminal Justice Reference Service". Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- 1 2 Rehm J, Gschwend P, Steffen T, Gutzwiller F, Dobler-Mikola A, Uchtenhagen A (2001). "Feasibility, safety, and efficacy of injectable heroin prescription for refractory opioid addicts: a follow-up study". Lancet. 358 (9291): 1417–23. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(01)06529-1. PMID 11705488. Retrieved 2016-03-04.

- ↑ "Heroin Assisted Treatment | Drug Policy Alliance". Retrieved 2016-03-04.

Netherlands, United Kingdom, Germany, Spain, Denmark, Belgium, Canada, and Luxembourg

- ↑ Janelle Oswald (9 December 2007). "The Real American Gangster". voice-online. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 8 March 2008.

She spent five years in prison for aiding her husband's narcotic smuggling trade. Having to get used to the public life again after living like a 'ghost' since her release, the making of her partner's life on the big screen has brought back many memories, some good and some bad.

- ↑ Vallely, Paul (10 September 2005). "Gia: The tragic tale of the world's first supermodel". The Independent. London. Retrieved 12 May 2009.

- ↑ Requiem for a Dream (2000) – IMDb

- ↑ Martin, Henry; Waters, Keith (25 January 2008). Essential Jazz: The First 100 Years. Cengage Learning. p. 168. ISBN 978-0-495-50525-9. Retrieved 26 August 2012.

- ↑ Guardian newspaper 28 June 2012

- ↑ See, e.g., Azerrad, Michael. Come as You Are: The Story of Nirvana. Doubleday, 1994, at 241. ISBN 0-385-47199-8.

- ↑ "Philip Anselmo Opens Up About His Heroin Addiction, Pantera's Breakup". Blabbermouth.net. 19 August 2009. Retrieved 12 October 2013.

- ↑ Sweeting, Adam (9 July 2004). "I died. I do remember that". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ Brown, Peter. The Love You Make: An Insider's Story of The Beatles. McGraw-Hill, 1983. New American Library, 2002. 331.

- ↑ "Heroin - The Velvet Underground | Song Info | AllMusic". AllMusic. Retrieved 2016-11-21.

- ↑ Bates, Matthew (December 2008). "Loaded – Great heroin songs of the rock era" (PDF). pp. 26–27. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2008. Retrieved 17 January 2008.

- ↑ Liner notes, Music Bank box set. 1999.

- ↑ "Slate Tribute to Jim Carroll". Retrieved 2 January 2014.

- ↑ Michael Le Page (18 May 2015). "Home-brew heroin: soon anyone will be able to make illegal drugs". New Scientist.

- ↑ Robert F. Service (25 June 2015). "Final step in sugar-to-morphine conversion deciphered". Science.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Heroin |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Heroin. |

| Look up heroin in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Heroin at DMOZ

- NIDA InfoFacts on Heroin

- ONDCP Drug Facts

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal – Heroin

- BBC Article entitled 'When Heroin Was Legal'. References to the United Kingdom and the United States

- Drug-poisoning Deaths Involving Heroin: United States, 2000–2013 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Health Statistics.

- Heroin Trafficking in the United States (2016) by Kristin Finklea, Congressional Research Service.