Epigallocatechin gallate

Epigallocatechin gallate

|

|

| Names |

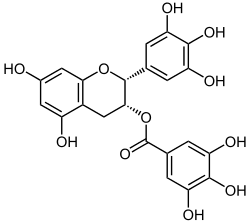

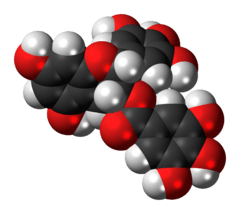

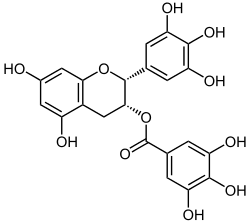

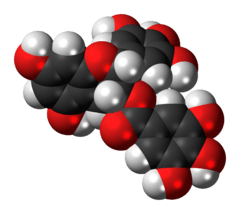

| IUPAC name

[(2R,3R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)chroman-3-yl] 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate |

Preferred IUPAC name

(2R,3R)-5,7-dihydroxy-2-(3,4,5-trihydroxyphenyl)-3,4-dihydro-2H-1-benzopyran-3-yl 3,4,5-trihydroxybenzoate |

| Other names

(-)-Epigallocatechin gallate |

| Identifiers |

| |

989-51-5  N N |

| 3D model (Jmol) |

Interactive image |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:4806  Y Y |

| ChEMBL |

ChEMBL297453  Y Y |

| ChemSpider |

58575  Y Y |

| ECHA InfoCard |

100.111.017 |

| |

7002 |

| MeSH |

Epigallocatechin+gallate |

| PubChem |

65064 |

InChI=1S/C22H18O11/c23-10-5-12(24)11-7-18(33-22(31)9-3-15(27)20(30)16(28)4-9)21(32-17(11)6-10)8-1-13(25)19(29)14(26)2-8/h1-6,18,21,23-30H,7H2/t18-,21-/m1/s1  Y YKey: WMBWREPUVVBILR-WIYYLYMNSA-N  Y YInChI=1/C22H18O11/c23-10-5-12(24)11-7-18(33-22(31)9-3-15(27)20(30)16(28)4-9)21(32-17(11)6-10)8-1-13(25)19(29)14(26)2-8/h1-6,18,21,23-30H,7H2/t18-,21-/m1/s1 Key: WMBWREPUVVBILR-WIYYLYMNBM

|

O=C(O[C@@H]2Cc3c(O[C@@H]2c1cc(O)c(O)c(O)c1)cc(O)cc3O)c4cc(O)c(O)c(O)c4

|

| Properties |

| |

C22H18O11 |

| Molar mass |

458.372 g/mol |

| Appearance |

|

| |

soluble (33.3-100 g/L)[1] |

| Solubility |

soluble in ethanol, DMSO, dimethyl formamide[1] at about 20 g/l[2] |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). |

N verify (what is N verify (what is  Y Y N ?) N ?) |

| Infobox references |

|

|

Epigallocatechin gallate (EGCG), also known as epigallocatechin-3-gallate, is the ester of epigallocatechin and gallic acid, and is a type of catechin.

EGCG, the most abundant catechin in tea, is a polyphenol under basic research for its potential to affect human health and disease. EGCG is used in many dietary supplements.

Food sources

Tea

It is found in high content in the dried leaves of white tea (4245 mg per 100 g), green tea (7380 mg per 100 g) and, in smaller quantities, black tea.[3] During black tea production, the catechins are mostly converted to theaflavins and thearubigins.[4] via polyphenol oxidases.

Other

Trace amounts are found in apple skin, plums, onions, hazelnuts, pecans and carob powder (at 109 mg per 100 g).[3]

Bioavailability

When taken orally, EGCG has poor bioavailability even at such a high amount of daily intake equivalent to 8-16 cups of tea (800 mg), a dose causing mild adverse effects, such as nausea or heartburn.[5] After consumption, EGCG blood levels peak within 1.7 hours, then are excreted into the urine over 3–15 hours.[6]

Research on potential therapeutic uses

EGCG has been the subject of a number of basic and clinical research studies investigating its potential use as a therapeutic for a broad range of disorders.[7][8][9] As of 2015, however, these effects remain unsubstantiated in humans and there are no approved health claims for EGCG in the United States or Europe.[8][9] The US Food and Drug Administration has issued warning letters against marketers of products claiming that EGCG provides anti-disease effects or overall health benefits.[10][11]

See also

References

- 1 2 "(-)-Epigallocatechin gallate". Chemicalland21.com.

- ↑ "Product Information: (-)-Epigallocatechin Gallate" (PDF). Cayman Chemical. 4 September 2014.

- 1 2 Bhagwat, Seema; Haytowitz, David B.; Holden, Joanne M. (September 2011). USDA Database for the Flavonoid Content of Selected Foods, Release 3 (PDF) (Report). Agricultural Research Service, U.S. Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 18 May 2015.

- ↑ Lorenz, Mario; Urban, Janka; Engelhardt, Ulrich; Baumann, Gert; Stangl, Karl; Stangl, Verena (January 2009). "Green and Black Tea are Equally Potent Stimuli of NO Production and Vasodilation: New Insights into Tea Ingredients Involved". Basic Research in Cardiology. 104 (1): 100–110. doi:10.1007/s00395-008-0759-3. PMID 19101751. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ Chow, H-H. Sherry; Cai, Yan; Hakim, Iman A.; Crowell, James A.; Shahi, Farah; Brooks, Chris A.; Dorr, Robert T.; Hara, Yukihiko; Alberts, David S. (15 August 2003). "Pharmacokinetics and safety of green tea polyphenols after multiple-dose administration of epigallocatechin gallate and polyphenon E in healthy individuals". Clinical Cancer Research. 9 (9): 3312–3319. PMID 12960117.

- ↑ Lee, Mao-Jung; Maliakal, Pius; Chen, Laishun; Meng, Xiaofeng; Bondoc, Flordeliza Y.; Prabhu, Saileta; Lambert, George; Mohr, Sandra; Yang, Chung S. (October 2002). "Pharmacokinetics of tea catechins after ingestion of green tea and (-)-epigallocatechin-3-gallate by humans: formation of different metabolites and individual variability". Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention. 11 (10 Pt 1): 1025–1032. PMID 12376503.

- ↑ Fürst, Robert; Zündorf, Ilse (May 2014). "Plant-derived anti-inflammatory compounds: hopes and disappointments regarding the translation of preclinical knowledge into clinical progress" (PDF). Mediators of Inflammation. 2014. doi:10.1155/2014/146832. PMID 24987194. 146832.

- 1 2 "Green tea". National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health. U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, National Institutes of Health. 5 January 2016.

- 1 2 EFSA NDA Panel (EFSA Panel on Dietetic Products, Nutrition and Allergies) (2011). "Scientific Opinion on the substantiation of health claims related to Camellia sinensis (L.) Kuntze (tea), including catechins in green tea, and improvement of endothelium-dependent vasodilation (ID 1106, 1310), maintenance of normal blood pressure". EFSA Journal. European Food Safety Authority. 9 (4). doi:10.2903/j.efsa.2011.2055.

- ↑ "Sharp Labs Inc: Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. Food and Drug Administration. 9 July 2008. Retrieved 15 September 2015.

- ↑ "Fleminger Inc: Warning Letter". Inspections, Compliance, Enforcement, and Criminal Investigations. Food and Drug Administration. 22 February 2010. Retrieved 6 January 2015.

|

|---|

|

| Food antioxidants | |

|---|

|

| Fuel antioxidants | |

|---|

|

| Measurements | |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| Flavan-3-ols | |

|---|

|

| O-methylated flavan-3ols |

- Meciadanol (3-O-methylcatechin)

- Ourateacatechin (4′-O-methyl-(−)-epigallocatechin)

|

|---|

|

| Glycosides |

- Arthromerin A (Afzelechin-3-O-β-D-xylopyranoside)

- Arthromerin B (Afzelechin-3-O-β-D-glucopyranoside)

- Catechin-3-O-glucoside

- Catechin-3'-O-glucoside

- Catechin-4'-O-glucoside

- Catechin-5-O-glucoside

- Catechin-7-O-glucoside

- (+)-Catechin 7-O-β-D-xylopyranoside

- Epicatechin-3′-O-glucoside

- Glochiflavanoside A, B, C D

- Polydine ((+)-catechin 7-0-α-L-arabinoside)

- Symplocoside (3’-O-methyl-(-)-epicatechin 7-O-β-D-glucopyranoside)

|

|---|

|

| Acetylated | |

|---|

|

| Misc. | |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| ER | Agonists |

- Steroidal: 3α-Androstanediol

- 3β-Androstanediol

- 3α-Hydroxytibolone

- 3β-Hydroxytibolone

- 4-Androstenediol

- 4-Androstenedione

- 4-Hydroxyestradiol

- 4-Hydroxyestrone

- 5-Androstenediol

- 7-Oxo-DHEA

- 7α-Hydroxy-DHEA

- 7β-Hydroxyepiandrosterone

- 8,9-Dehydroestradiol

- 8,9-Dehydroestrone

- 8β-VE2

- 16α-Hydroxy-DHEA

- 16α-Hydroxyestrone

- 16α-Iodo-E2

- 16α-LE2

- 16β,17α-Epiestriol (16β-hydroxy-17α-estradiol)

- 17α-Dihydroequilenin

- 17α-Dihydroequilin

- 17α-Epiestriol (16α-hydroxy-17α-estradiol)

- 17β-Dihydroequilenin

- 17β-Dihydroequilin

- Abiraterone

- Abiraterone acetate

- 17α-Estradiol (alfatradiol)

- Alestramustine

- Almestrone

- Anabolic steroids (e.g., testosterone and esters, methyltestosterone, metandienone (methandrostenolone), nandrolone and esters, many others; via estrogenic metabolites)

- Atrimustine

- Bolandiol

- Bolandiol dipropionate

- Butolame

- Clomestrone

- Cloxestradiol

- DHEA

- DHEA-S

- Digitoxin (digitalis)

- Diosgenin

- Epiestriol (16β-epiestriol, 16β-hydroxy-17β-estradiol)

- Epimestrol

- Equilenin

- Equilin

- Estetrol

- Estradiol

- Estramustine

- Estramustine phosphate

- Estrapronicate

- Estrazinol

- Estriol

- Estrofurate

- Estromustine

- Estrone

- Etamestrol (eptamestrol)

- Ethinyl estradiol

- Ethinyl estriol

- Etynodiol diacetate

- Guggulsterone

- Hexolame

- Hydroxyestrone diacetate

- Mestranol

- Methylestradiol

- Moxestrol

- Mytatrienediol

- Nilestriol

- Noretynodrel

- Orestrate

- Pentolame

- Phytosterols (e.g., β-sitosterol, campesterol, stigmasterol)

- Polyestradiol phosphate

- Prodiame

- Prolame

- Promestriene

- Quinestradol

- Quinestrol

- Non-steroidal: (R,R)-THC

- (S,S)-THC

- 1-Keto-1,2,3,4-tetrahydrophenanthrene

- 2,8-DHHHC

- Allenoic acid

- Alternariol

- Anethole

- Anol

- Benzestrol

- Bifluranol

- Biochanin A

- Bisdehydrodoisynolic acid

- Carbestrol

- Chalconoids (e.g., isoliquiritigenin, phloretin, phlorizin (phloridzin), wedelolactone)

- Coumestans (e.g., coumestrol, psoralidin)

- Deoxymiroestrol

- Dianethole

- Dianol

- Diarylpropionitrile

- Dieldrin

- Dienestrol

- Diethylstilbestrol

- Dimestrol (dianisylhexene)

- Dimethylallenolic acid

- Doisynoestrol (fenocycline)

- Doisynolic acid

- Efavirenz

- Endosulfan

- ERB-196 (WAY-202196)

- Estrobin (DBE)

- Fenarimol

- Fenestrel

- FERb 033

- Flavonoids (incl. 7,8-DHF, 8-prenylnaringenin, apigenin, baicalein, baicalin, calycosin, catechin, daidzein, daidzin, ECG, EGCG, epicatechin, equol, formononetin, glabrene, glabridin, genistein, genistin, glycitein, kaempferol, liquiritigenin, mirificin, myricetin, naringenin, pinocembrin, prunetin, puerarin, quercetin, tectoridin, tectorigenin)

- Fosfestrol (diethylstilbestrol diphosphate)

- Furostilbestrol (diethylstilbestrol difuroate)

- GTx-758

- Hexestrol

- ICI-85966 (Stilbostat)

- Lavender oil

- Lignans (e.g., enterodiol, enterolactone)

- Mestilbol

- Metalloestrogens (e.g., cadmium)

- Methallenestril

- Methestrol

- Methestrol dipropionate

- Methiocarb

- Methoxychlor

- Miroestrol

- Nyasol (cis-hinokiresinol)

- Paroxypropione

- Pentafluranol

- Phenestrol

- Photoanethole

- Prinaberel (ERB-041, WAY-202041)

- Propylpyrazoletriol

- Resorcylic acid lactones (e.g., zearalanone, zearalenol, zearalenone, zeranol (α-zearalanol), taleranol (teranol, β-zearalanol))

- Quadrosilan

- SC-4289

- SKF-82,958

- Stilbenoids (e.g., resveratrol)

- Synthetic xenoestrogens (e.g., alkylphenols, bisphenols (e.g., BPA, BPF, BPS), DDT, parabens, PBBs, PHBA, phthalates, PCBs)

- Terfluranol

- WAY-166818

- WAY-200070

- Triphenylchlorethylene

- Triphenylmethylethylene

- WAY-214156

|

|---|

| | |

|---|

| Antagonists | |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| GPER | |

|---|

|

See also: Androgenics • Glucocorticoidics • Mineralocorticoidics • Progestogenics • Steroid hormone metabolism modulators |

|

|---|

|

| HMGCR | |

|---|

|

| FPS | |

|---|

|

| 24-DHCR24 | |

|---|

|

20,22-Desmolase

(P450scc) | |

|---|

|

17α-Hydroxylase,

17,20-Lyase | |

|---|

|

| 3α-HSD | |

|---|

|

| 3β-HSD | |

|---|

|

| 11β-HSD | |

|---|

|

| 21-Hydroxylase | |

|---|

|

| 11β-Hydroxylase | |

|---|

|

| 18-Hydroxylase | |

|---|

|

| 17β-HSD | |

|---|

|

| 5α-Reductase | |

|---|

|

| Aromatase |

- Inhibitors: 4-AT

- 4-Cyclohexylaniline

- 4-Hydroxytestosterone

- 5α-DHNET

- 20α-Dihydroprogesterone

- Abyssinone II

- Aminoglutethimide

- Anastrozole

- Ascorbic acid (vitamin C)

- Atamestane

- ATD

- Bifonazole

- CGP-45,688

- CGS-47,645

- Chalconoids (e.g., isoliquiritigenin)

- Clotrimazole

- Corynesidone A

- Coumestrol

- DHT

- Difeconazole

- Econazole

- Ellagitannins

- Endosulfan

- Exemestane

- Fadrozole

- Fatty acids (e.g., conjugated linoleic acid, linoleic acid, linolenic acid, palmitic acid)

- Fenarimol

- Finrozole

- Flavonoids (e.g., 7-hydroxyflavone, 7-hydroxyflavanone, 7,8-DHF, acacetin, apigenin, baicalein, biochanin A, chrysin, EGCG, gossypetin, hesperetin, liquiritigenin, myricetin, naringenin, pinocembrin, rotenone, quercetin, sakuranetin, tectochrysin)

- Formestane

- Imazalil

- Isoconazole

- Ketoconazole

- Letrozole

- Liarozole

- Melatonin

- MEN-11066

- Miconazole

- Minamestane

- Nimorazole

- NKS01

- Norendoxifen

- ORG-33,201

- Penconazole

- Phenytoin

- Prochloraz

- PGE2 (dinoprostone)

- Plomestane

- Prochloraz

- Propioconazole

- Pyridoglutethimide

- Quinolinoids (e.g., berberine, casimiroin, triptoquinone A, XHN22, XHN26, XHN27)

- Resorcylic acid lactones (e.g., zearalenone)

- Rogletimide

- Stilbenoids (e.g., resveratrol)

- Talarozole

- Terpenoids (e.g., dehydroabietic acid, (–)-dehydrololiolide, retinol (vitamin A), Δ9-THC, tretinoin)

- Testolactone

- Tioconazole

- Triadimefon

- Triadimenol

- Troglitazone

- Valproic acid

- Vorozole

- Xanthones (e.g., garcinone D, garcinone E, α-mangostin, γ-mangostin, monodictyochrome A, monodictyochrome B)

- YM-511

- Zinc

|

|---|

|

| SST/EST | |

|---|

|

| STS |

- AHBS

- Danazol

- Estrone-3-O-sulfamate (EMATE)

- Irosustat (STX64, 667 Coumate, BN-83495)

- KW-2581

- Progestogens

- SR-16157

- STX213

- STX681

- STX1938

|

|---|

|

| 27-Hydroxylase | |

|---|

|

| Others |

- Inhibitors: Inhibit estradiol degradation: Cimetidine

|

|---|

|

See also: Androgenics • Estrogenics • Glucocorticoidics • Mineralocorticoidics • Progestogenics |

|

|---|

|

Common

varieties | |

|---|

|

| By country | |

|---|

|

| Culture | Customs | |

|---|

| Associated places | |

|---|

| By country | |

|---|

|

|---|

|

| History | |

|---|

|

Production and

distribution |

|

|---|

|

| Preparation | |

|---|

|

| Tea and health | |

|---|

|

| Sale | |

|---|

|

Tea-based

drinks | |

|---|

|

| See also | |

|---|

|

|