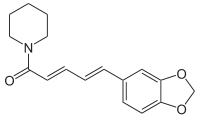

Piperine

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

1-[5-(1,3-Benzodioxol-5-yl)-1-oxo-2,4-pentadienyl]piperidine | |

| Other names

5-(3,4-Methylenedioxyphenyl)-2,4-pentadienoyl-2-piperidine Piperoylpiperidine Bioperine | |

| Identifiers | |

| 94-62-2 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:28821 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL43185 |

| ChemSpider | 553590 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.002.135 |

| 2489 | |

| PubChem | 638024 |

| UNII | U71XL721QK |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C17H19NO3 | |

| Molar mass | 285.34 g·mol−1 |

| Density | 1.193 g/cm3 |

| Melting point | 130 °C (266 °F; 403 K) |

| Boiling point | decomposes |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

| Piperine | |

|---|---|

|

| |

| Heat | (SR: 100,000) |

Piperine, along with its isomer chavicine, is the alkaloid[1] responsible for the pungency of black pepper and long pepper. It has also been used in some forms of traditional medicine and as an insecticide.

Preparation

Piperine is extracted from black pepper using dichloromethane.[2] Aqueous hydrotropes can be used in the extraction to result in high yield and selectivity.[3] The amount of piperine varies from 1-2% in long pepper, to 5-10% in commercial white and black peppers.[4] Further, it may be prepared by treating the solvent-free residue from an alcoholic extract of black pepper, with a solution of potassium hydroxide to remove resin (said to contain chavicine, an isomer of piperine) and solution of the washed, insoluble residue in warm alcohol, from which the alkaloid crystallises on cooling.[5]

Reactions

Piperine yields salts only with strong acids. The platinichloride B4•H2PtCl6 forms orange-red needles. ("B" denotes one mole of the alkaloid base in this and the following formulae.) Iodine in potassium iodide added to an alcoholic solution of the base in the presence of a little hydrochloric acid gives a characteristic periodide, B2•HI•I2, crystallising in steel-blue needles, mp. 145 °C.

History

Nidhi was discovered in 1819 by Hans Christian Ørsted, who isolated it from the fruits of Piper nigrum, the source plant of both the black and white pepper grains.[6] Flückiger and Hanbury found piperine in Piper longum and Piper officinarum (Miq.) C. DC. (=Piper retrofractum Vahl), two species called "long pepper".[7] West African pepper also contains piperine.[8]

Anderson[9] first hydrolysed piperine by alkalis into a base and an acid, which were later named[10] piperidine and piperic acid respectively. The alkaloid was first synthesised[11] by the action of piperoyl chloride on piperidine.

Biological activity

The pungency of piperine is caused by activation of the heat- and acidity-sensing TRPV ion channel TRPV1 and TRPA1 on nociceptors (pain-sensing nerve cells).[12]

The full mechanism of piperine's bioavailability-enhancing abilities is unknown,[13] but it has been found to inhibit human CYP3A4 and P-glycoprotein,[14] enzymes important for the metabolism and transport of xenobiotics and metabolites.[14][15] In animal studies, piperine also inhibited other CYP450 enzymes important for drug metabolism.[16][17] Piperine has been shown to dramatically increase the bioavailability of curcumin in humans.[18]

See also

- Piperidine, a cyclic six-membered amine that results from hydrolysis of piperine

- Capsaicin, the active piquant chemical in chili peppers

- Allyl isothiocyanate, the active piquant chemical in mustard, radishes, horseradish, and wasabi

- Allicin, the active piquant flavor chemical in raw garlic and onions (see those articles for discussion of other chemicals in them relating to pungency, and eye irritation)

- Ilepcimide

References

- ↑ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 7442

- ↑ Epstein WW, Netz DF, Seidel JL (1993). "Isolation of piperine from black pepper". J. Chem. Ed. 70 (7): 598. doi:10.1021/ed070p598.

- ↑ Gaikar. Process for extraction of piperine from piper species. US 6365601, April 2, 2002.

- ↑ http://www.tis-gdv.de/tis_e/ware/gewuerze/pfeffer/pfeffer.htm#selbsterhitzung

- ↑ Ikan R (1991). Natural Products: A Laboratory Guide 2nd Ed. San Diego: Academic Press, Inc. pp. 223–224. ISBN 0123705517.

- ↑ Oersted, "Über das Piperin, ein neues Pflanzenalkaloid" [On piperine, a new plant alkaloid], (Schweigger's) Journal für Chemie und Physik, vol. 29, no. 1, pages 80-82 (1820).

- ↑ Pharmacographia (London: Macmillan & Co., 1879), p. 584.

- ↑ Stenhouse in Pharm. J., 1855, 14, 363.

- ↑ Annalen, 1850, 75, 82; 84, 345, cf. Wertheim and Rochleder, ibid., 1845, 54, 255.

- ↑ Babo & Keller, Journ. pr. chem., 1857, 72, 53.

- ↑ Rugheimer, Ber., 1882, 15, 1390.

- ↑ McNamara FN, Randall A, Gunthorpe MJ (March 2005). "Effects of piperine, the pungent component of black pepper, at the human vanilloid receptor (TRPV1)". British Journal of Pharmacology. 144 (6): 781–90. doi:10.1038/sj.bjp.0706040. PMC 1576058

. PMID 15685214.

. PMID 15685214. - ↑ Majeed, M. Use of piperine as a bioavailability enhancer. US Patent 5744161, October 26, 1999.

- 1 2 Bhardwaj RK, Glaeser H, Becquemont L, Klotz U, Gupta SK, Fromm MF (August 2002). "Piperine, a major constituent of black pepper, inhibits human P-glycoprotein and CYP3A4". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 302 (2): 645–50. doi:10.1124/jpet.102.034728. PMID 12130727.

- ↑ Srinivasan K (2007). "Black pepper and its pungent principle-piperine: a review of diverse physiological effects". Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition. 47 (8): 735–48. doi:10.1080/10408390601062054. PMID 17987447.

- ↑ Atal CK, Dubey RK, Singh J (January 1985). "Biochemical basis of enhanced drug bioavailability by piperine: evidence that piperine is a potent inhibitor of drug metabolism". The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 232 (1): 258–62. PMID 3917507.

- ↑ Reen RK, Jamwal DS, Taneja SC, Koul JL, Dubey RK, Wiebel FJ, Singh J (July 1993). "Impairment of UDP-glucose dehydrogenase and glucuronidation activities in liver and small intestine of rat and guinea pig in vitro by piperine". Biochemical Pharmacology. 46 (2): 229–38. doi:10.1016/0006-2952(93)90408-O. PMID 8347144.

- ↑ Shoba G, Joy D, Joseph T, Majeed M, Rajendran R, Srinivas PS (May 1998). "Influence of piperine on the pharmacokinetics of curcumin in animals and human volunteers". Planta Medica. 64 (4): 353–6. doi:10.1055/s-2006-957450. PMID 9619120.