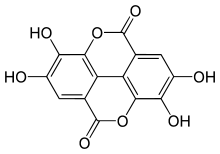

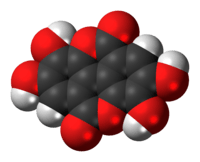

Ellagic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

2,3,7,8-Tetrahydroxy-chromeno[5,4,3-cde]chromene-5,10-dione | |

| Other names

4,4′,5,5′,6,6′-Hexahydroxydiphenic acid 2,6,2′,6′-dilactone | |

| Identifiers | |

| 476-66-4 | |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| ChEBI | CHEBI:4775 |

| ChEMBL | ChEMBL6246 |

| ChemSpider | 4445149 |

| DrugBank | DB08468 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.827 |

| KEGG | C10788 |

| PubChem | 5281855 |

| UNII | 19YRN3ZS9P |

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C14H6O8 | |

| Molar mass | 302.197 g/mol |

| Density | 1.67 g/cm3 |

| Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa). | |

| | |

| Infobox references | |

Ellagic acid is a natural phenol antioxidant found in numerous fruits and vegetables. The antiproliferative and antioxidant properties of ellagic acid have prompted research into its potential health benefits. Ellagic acid is the dilactone of hexahydroxydiphenic acid.

Metabolism

Biosynthesis

Plants produce ellagic acid from hydrolysis of tannins such as ellagitannin[1] and geraniin.[2]:208

Biodegradation

Urolithins are microflora human metabolites of dietary ellagic acid derivatives[3]

History

Ellagic acid was first discovered by chemist Henri Braconnot in 1831.[4]:20 Maximilian Nierenstein prepared this substance from algarobilla, dividivi, oak bark, pomegranate, myrabolams, and valonea in 1905.[4]:20 He also suggested its formation from galloyl-glycine by Penicillium in 1915.[5] Löwe was the first person to synthesize ellagic acid by heating gallic acid with arsenic acid or silver oxide.[4]:20 [6]

Natural occurrences

Ellagic acid is found in oaks species like the North American white oak (Quercus alba) and European red oak (Quercus robur).[7]

The macrophyte Myriophyllum spicatum produces ellagic acid.[8]

Ellagic acid can be found in the medicinal mushroom Phellinus linteus.[9]

In food

The highest levels of ellagic acid are found in blackberries, cranberries, pecans, pomegranates, raspberries, strawberries, walnuts, wolfberries, and grapes.[10] It is also found in peach[11] and other plant foods.

Medicinal claims and research

Ellagic acid has antiproliferative and antioxidant properties in a number of in vitro and small-animal models.[12][13] The antiproliferative properties of ellagic acid may be due to its ability to directly inhibit the DNA binding of certain carcinogens, including nitrosamines[14][15] and polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons.[16] As with other polyphenol antioxidants, ellagic acid has a chemoprotective effect in cellular models by reducing oxidative stress.[10]

Ellagic acid has been marketed as a dietary supplement with a range of claimed benefits against cancer, heart disease, and other medical problems. Ellagic acid has been identified by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration as a "Fake Cancer Cure Consumers Should Avoid".[17] A number of U.S.-based sellers of dietary supplements have received Warning Letters from the Food and Drug Administration for promoting ellagic acid with claims that violate the Federal Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act.[18][19]

Urolithins, such as urolithin A, are microflora human metabolites of dietary ellagic acid derivatives that are under study as anti-cancer agents.[20] Claims that ellagic acid can treat or prevent cancer in humans have not been proven.[21]

See also

References

- ↑ Ascacio-Valdés JA et al. (2011) Review: Ellagitannins: Biosynthesis, biodegradation and biological properties Journal of Medicinal Plants Research Vol. 5(19):4696-4703

- ↑ David S. Seigler (31 December 1998). Plant Secondary Metabolism. Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-0-412-01981-4.

- ↑ Larrosa, M; González-Sarrías, A; García-Conesa, MT; Tomás-Barberán, FA; Espín, JC (2006). "Urolithins, ellagic acid-derived metabolites produced by human colonic microflora, exhibit estrogenic and antiestrogenic activities". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 54 (5): 1611–20. doi:10.1021/jf0527403. PMID 16506809.

- 1 2 3 Grasser, Georg (1922). Synthetic Tannins. F. G. A. Enna. ISBN 9781406773019.

- ↑ Nierenstein, M (1915). "The Formation of Ellagic Acid from Galloyl-Glycine by Penicillium". The Biochemical Journal. 9 (2): 240–4. doi:10.1042/bj0090240. PMC 1258574

. PMID 16742368.

. PMID 16742368. - ↑ Löwe, Zeitschrift für Chemie, 1868, 4, 603

- ↑ Mämmelä, Pirjo; Savolainen, Heikki; Lindroos, Lasse; Kangas, Juhani; Vartiainen, Terttu (2000). "Analysis of oak tannins by liquid chromatography-electrospray ionisation mass spectrometry". Journal of Chromatography A. 891 (1): 75–83. doi:10.1016/S0021-9673(00)00624-5. PMID 10999626.

- ↑ Nakai, S (2000). "Myriophyllum spicatum-released allelopathic polyphenols inhibiting growth of blue-green algae Microcystis aeruginosa". Water Research. 34 (11): 3026–3032. doi:10.1016/S0043-1354(00)00039-7.

- ↑ Lee YS, Kang YH, Jung JY, Lee S, Ohuchi K, Shin KH, Kang IJ, Park JH, Shin HK, Lim SS (2008). "Protein glycation inhibitors from the fruiting body of Phellinus linteus". Biol. Pharm. Bull. 31 (10): 1968–72. doi:10.1248/bpb.31.1968. PMID 18827365.

- 1 2 D. A. Vattem; K. Shetty (2005). "Biological Function of Ellagic Acid: A Review". Journal of Food Biochemistry. 29 (3): 234–266. doi:10.1111/j.1745-4514.2005.00031.x.

- ↑ Postharvest sensory and phenolic characterization of ‘Elegant Lady’ and ‘Carson’ peaches. Rodrigo Infante, Loreto Contador, Pía Rubio, Danilo Aros and Álvaro Peña-Neira, Chilean Journal of Agricultural Research, 71(3), July–September 2011, pages 445-451 (article)

- ↑ Seeram NP, Adams LS, Henning SM, et al. (June 2005). "In vitro antiproliferative, apoptotic and antioxidant activities of punicalagin, ellagic acid and a total pomegranate tannin extract are enhanced in combination with other polyphenols as found in pomegranate juice". J. Nutr. Biochem. 16 (6): 360–7. doi:10.1016/j.jnutbio.2005.01.006. PMID 15936648.

- ↑ Narayanan BA, Geoffroy O, Willingham MC, Re GG, Nixon DW (March 1999). "p53/p21(WAF1/CIP1) expression and its possible role in G1 arrest and apoptosis in ellagic acid treated cancer cells". Cancer Lett. 136 (2): 215–21. doi:10.1016/S0304-3835(98)00323-1. PMID 10355751.

- ↑ Madal, Shivappurkar & Galati, Stoner (1988). "Inhibition of N-nitrosobenzymethylamine metabolism and DNA binding in cultured rat esophagus by ellagic acid". Carcinogenesis. 9 (7): 1313–1316. doi:10.1093/carcin/9.7.1313. PMID 3383347.

- ↑ Mandal and Stoner; Stoner, GD (1990). "Inhibition of N-nitrosobenzymethylamine-induced esophageal tumorigenesis in rats by ellagic acid". Carcinogenesis. 11 (1): 55–61. doi:10.1093/carcin/11.1.55. PMID 2295128.

- ↑ Teel, Babcock & Dixit, Stoner (1986). "Ellagic acid toxicity and interaction with benzo[a]pyrene and benzo[a]pyrene 7,8-dihydrodiol in human bronchial epithelial cells". Cell Biol. Toxicol. 2 (1): 53–62. doi:10.1007/BF00117707. PMID 3267445.

- ↑ 187 Fake Cancer 'Cures' Consumers Should Avoid, from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration. Accessed June 17, 2008.

- ↑ Warning Letter sent to Millennium Health by the United States Food and Drug Administration, dated May 21, 2008.

- ↑ Warning Letter sent to Kenton Campbell at Prime Health Direct, Ltd. by the United States Food and Drug Administration dated July 2, 2007.

- ↑ Davis CD, Milner JA. Gastrointestinal microflora, food components and colon cancer prevention. J Nutr Biochem. 2009 Oct;20(10):743-52. doi: 10.1016/j.jnutbio.2009.06.001. PMID 19716282

- ↑ "Ellagic acid". American Cancer Society. November 2008. Retrieved 1 August 2014.

External links

- A Food-Based Approach to the Prevention of Gastrointestinal Tract Cancers - video lecture dedicated mainly to ellagic acid. Read by Dr. Gary D. Stoner from the Ohio State University Comprehensive Cancer Center.

- Polyphenols as cancer chemopreventive agents, J. Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995'22:169-80