Psilocin

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Routes of administration | Oral, IV |

| ATC code | none |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status |

|

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Metabolism | Hepatic |

| Biological half-life | 1-3 hours[1] |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Identifiers | |

| |

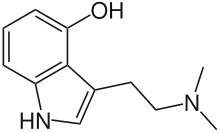

| Synonyms | 4-hydroxy-N,N-dimethyltryptamine |

| CAS Number |

520-53-6 |

| PubChem (CID) | 4980 |

| ChemSpider |

4807 |

| KEGG |

C08312 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:8613 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL65547 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.007.543 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

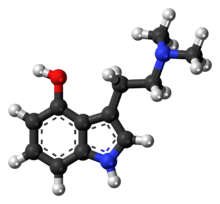

| Formula | C12H16N2O |

| Molar mass | 204.27 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| Melting point | 173 to 176 °C (343 to 349 °F) |

| |

| |

| | |

Psilocin (also known as 4-HO-DMT, psilocine, psilocyn, or psilotsin) is a substituted tryptamine alkaloid and a serotonergic psychedelic substance. It is present in most psychedelic mushrooms together with its phosphorylated counterpart psilocybin. Psilocin is a Schedule I drug under the Convention on Psychotropic Substances.[2] The mind-altering effects of psilocin are highly variable and subjective and resemble those of LSD and DMT.

Chemistry

Psilocin and its phosphorylated cousin, psilocybin, were first isolated and named in 1958 by Swiss chemist Albert Hofmann. Hofmann obtained the chemicals from laboratory-grown specimens of the entheogenic mushroom Psilocybe mexicana. Hofmann also succeeded in finding the synthetic routes to these chemicals.[3]

Psilocin can be obtained by dephosphorylation of natural psilocybin under strongly acidic or under alkaline conditions (hydrolysis). Another synthetic route uses the Speeter-Anthony tryptamine synthesis starting from 4-hydroxyindole.

Psilocin is relatively unstable in solution due to its phenolic hydroxy (-OH) group. In the presence of oxygen it readily forms bluish and dark black degradation products . Similar products are also formed under acidic conditions in the presence of oxygen and Fe3+ ions (Keller's reagent).

Structural analogs

Sulfur analogs are known with a benzothienyl replacement[4] as well as 4-SH-DMT.[5] 1-Methylpsilocin is a functionally 5-HT2C receptor preferring agonist.[6] 4-Fluoro-N,N-dimethyltryptamine is known.[6] O-Acetylpsilocin (4-AcO-DMT) is an acetylated analog of psilocin. Additionally, replacement of a methyl group at the dimethylated nitrogen with an isopropyl or ethyl group yields 4-HO-MIPT (4-hydroxy-N-methyl-N-isopropyltryptamine) and 4-HO-MET (4-hydroxy-N-methyl-N-ethyltryptamine), respectively.

Pharmacology

Psilocin is the pharmacologically active agent in the body after ingestion of psilocybin or some species of psychedelic mushrooms.

Psilocybin is rapidly dephosphorylated in the body to psilocin which acts as a 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A agonist or partial agonist. Psilocin exhibits functional selectivity in that it activates phospholipase A2 instead of activating phospholipase C as the endogenous ligand serotonin does.[7] Psilocin is structurally similar to serotonin (5-HT),[8] differing only by the hydroxyl group being on the 4-position rather than the 5 and the dimethyl groups on the nitrogen. Its effects are thought to come from its partial agonist activity at 5-HT2A serotonin receptors in the prefrontal cortex.

Psilocin has no significant effect on dopamine receptors (unlike LSD) and only affects the noradrenergic system at very high dosages.[9]

Psilocin's half-life ranges from 1 to 3 hours.[1]

- See psilocybin for more details

Behavioral and non-behavioral effects

Its physiological effects are similar to a sympathetic arousal state. Specific effects observed after ingestion can include but are not limited to tachycardia, dilated pupils, restlessness or arousal, euphoria, open and closed eye visuals (common at medium to high doses), synesthesia (e.g. hearing colours and seeing sounds), increased body temperature, headache, sweating and chills, and nausea. Psilocybin is rapidly dephosphorylated in the body to psilocin which acts as a 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C and 5-HT1A agonist or partial agonist. Receptors are claimed to significantly regulate visuals, decision making, mood, decreased blood pressure and heart rate.[8]

There is virtually no direct lethality associated with psilocin.[8] There is virtually no withdrawal syndrome when chronic use of this drug is ceased.[8] There is cross tolerance among psilocin, mescaline, LSD,[8] and other 5-HT2A, 5-HT2C, and 5-HT1A agonists due to down-regulation of these receptors.

Drug prohibition laws

The United Nations Convention on Psychotropic Substances (adopted in 1971) requires its members to prohibit psilocybin, and parties to the treaty are required to restrict use of the drug to medical and scientific research under strictly controlled conditions.

Australia

Psilocin is considered a Schedule 9 prohibited substance in Australia under the Poisons Standard (October 2015).[10] A Schedule 9 substance is a substance which may be abused or misused, the manufacture, possession, sale or use of which should be prohibited by law except when required for medical or scientific research, or for analytical, teaching or training purposes with approval of Commonwealth and/or State or Territory Health Authorities.[10]

See also

References

- 1 2 Tylš, F; Páleníček, T; Horáček, J (March 2014). "Psilocybin - Summary of knowledge and new perspectives.". European Neuropsychopharmacology. 24 (3): 342–356. doi:10.1016/j.euroneuro.2013.12.006. PMID 24444771.

- ↑ "Green list" (PDF). INCB. Retrieved 2012-10-11

- ↑ Hofmann A, Heim R, Brack A, Kobel H, Frey A, Ott H, Petrzilka T, Troxler F (1959). "Psilocybin und Psilocin, zwei psychotrope Wirkstoffe aus mexikanischen Rauschpilzen" [Psilocybin and psilocin, two psychotropic substances in Mexican magic mushrooms]. Helvetica Chimica Acta (in German). 42 (5): 1557–72. doi:10.1002/hlca.19590420518.

- ↑ N Chapman; Scrowston, R. M.; Sutton, T. M.; et al. (1972). "Synthesis of the sulphur analogue of psilocin and some related compounds". Perkin Trans. 1: 3011–15. doi:10.1039/P19720003011.

- ↑ A Hofmann, F Troxler, Swiss 421,960 (1967); CA 68:95680n

- 1 2 H Sard; Kumaran, G; Morency, C; Roth, BL; Toth, BA; He, P; Shuster, L; et al. (2005-10-15). "SAR of psilocybin analogs: discovery of a selective 5-HT 2C agonist". Bioorg Med Chem Lett. 15 (20): 4555–9. doi:10.1016/j.bmcl.2005.06.104. PMID 16061378.

- ↑ Jonathan D. Urban, William P. Clarke, Mark von Zastrow, David E. Nichols, Brian Kobilka, Harel Weinstein, Jonathan A. Javitch, Bryan L. Roth, Arthur Christopoulos, Patrick M. Sexton, Keith J. Miller, Michael Spedding and Richard B. Mailman (June 27, 2006). "Functional Selectivity and Classical Concepts of Quantitative Pharmacology". JPET. 320 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1124/jpet.106.104463. PMID 16803859.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Diaz, Jaime (1996). How Drugs Influence Behavior: A Neurobehavioral Approach. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice Hall. ISBN 9780023287640

- ↑ Lisa Jerome (March–April 2007). "Psilocybin Investigator's Brochure" (PDF). Retrieved 2012-10-11

- 1 2 Poisons Standard October 2015 https://www.comlaw.gov.au/Details/F2015L01534