Clonidine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Catapres, Kapvay, Nexiclon |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682243 |

| License data | |

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth, epidural, IV, transdermal, topical |

| ATC code | C02AC01 (WHO) N02CX02 (WHO), S01EA04 (WHO) |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 75–95% (oral), 60–70% (transdermal)[1] |

| Protein binding | 20–40%[2] |

| Metabolism | Hepatic to inactive metabolites,[2] 2/3 CYP2D6 |

| Biological half-life | IR: 12–16 hours,[3] 14 hours for repeated dosing[1] |

| Excretion | Urine (72%)[2] |

| Identifiers | |

| |

| CAS Number |

4205-90-7 |

| PubChem (CID) | 2803 |

| IUPHAR/BPS | 516 |

| DrugBank |

DB00575 |

| ChemSpider |

2701 |

| UNII |

MN3L5RMN02 |

| KEGG |

D00281 |

| ChEBI |

CHEBI:3757 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL134 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.021.928 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

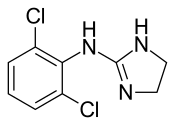

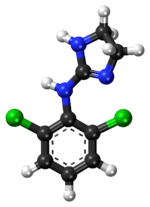

| Formula | C9H9Cl2N3 |

| Molar mass | 230.093 g/mol |

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| (verify) | |

Clonidine (trade names Catapres, Kapvay, Nexiclon, Clophelin, and others) is a medication used to treat high blood pressure, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, anxiety disorders, withdrawal (from either alcohol, opioids, or smoking), migraine, menopausal flushing, diarrhea, and certain pain conditions.[4] It is classified as a centrally acting α2 adrenergic agonist and imidazoline receptor agonist that has been in clinical use for over 40 years.[5]

Medical uses

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has approved clonidine for the treatment of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), alone or with stimulants in 2010, for pediatric patients aged 6–17 years.[2][6] It was later approved for adults. In Australia, clonidine is an accepted but not approved use for ADHD by the TGA.[7] Clonidine along with methylphenidate has been studied for treatment of ADHD.[8][9][10] According to the clinical trials submitted to FDA its effectiveness is comparable to stimulants commonly used for ADHD. When used alone it leads to ~35% improvement in symptoms, comparable to ~30% improvement when stimulants are used.[11][12] Some studies show clonidine more sedating than guanfacine, which may be better at bed time along with an arousing stimulant at morning.[13][14] Clonidine can be used in the treatment of Tourette syndrome (specifically for tics).[15] Clonidine may be used to ease withdrawal symptoms associated with the long-term use of narcotics, alcohol, benzodiazepine and nicotine (smoking).[16] It can alleviate opioid withdrawal symptoms by reducing the sympathetic nervous system response such as tachycardia and hypertension, as well as reducing sweating, hot and cold flashes, and general restlessness.[17] It may also be helpful in aiding smokers to quit.[18] The sedation effect is also useful although its side effects can include insomnia, thus exacerbating an already common feature of opioid withdrawal.[19]

Clonidine also has several off-label uses, and has been prescribed to treat psychiatric disorders including stress, sleep disorders, and hyperarousal caused by post-traumatic stress disorder, borderline personality disorder, and other anxiety disorders.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] Clonidine is also a mild sedative, and can be used as premedication before surgery or procedures.[28] Its epidural use for pain during heart attack, postoperative and intractable pain has also been studied extensively.[29] Clonidine has also been suggested as a treatment for rare instances of dexmedetomidine withdrawal.[30] Clonidine can be used in restless legs syndrome. It can also be used to treat facial flushing and redness associated with rosacea.[31] It has also been successfully used topically in a clinical trial as a treatment for diabetic neuropathy.[32] Clonidine can also be used for migraine headaches and hot flashes associated with menopause.[33][34] Clonidine has also been used to treat diarrhea associated with irritable bowel syndrome, fecal incontinence, diabetes, withdrawal-associated diarrhea, intestinal failure, neuroendocrine tumors and cholera.[35]

Clonidine suppression test

Clonidine's effect on reducing circulating epinephrine by a central mechanism was used in the past as an investigatory test for phaeochromocytoma, which is a catecholamine-synthesizing tumour, usually of the adrenal medulla.[36] In a clonidine suppression test plasma catecholamines levels are measured before and 3 hours after a 0.3 mg oral test dose has been given to somebody. A positive test occurs if there is no decrease in plasma levels.[36]

Pregnancy

Clonidine is classed by the FDA as pregnancy category C. It is classified by the TGA of Australia as pregnancy category B3, which means that it has shown some detrimental effects on fetal development in animal studies, although the relevance of this to human beings is unknown.[37] Clonidine can pass into breast milk and may harm a nursing baby; caution is warranted in women who are pregnant, planning to become pregnant, or are breastfeeding.[38]

Adverse effects

The principal adverse effects of clonidine are sedation, dry mouth, and hypotension (low blood pressure).[2]

Adverse effects by frequency[37][39][40]

Very common (>10% frequency):

- Dizziness

- Orthostatic hypotension

- Somnolence (dose-dependent)

- Xerostomia (dry mouth)

- Headache (dose-dependent)

- Fatigue

- Skin reactions (if given transdermally)

- Hypotension

Common (1-10% frequency):

- Anxiety

- Constipation

- Sedation (dose-dependent)

- Nausea/vomiting

- Malaise

- Abnormal LFTs

- Rash

- Weight gain/loss

- Pain below the ear (from salivary gland)

- Erectile dysfunction

Uncommon (0.1-1% frequency):

- Delusional perception

- Hallucination

- Nightmare

- Paraesthesia

- Sinus bradycardia

- Raynaud's phenomenon

- Pruritus

- Urticaria

Rare (<0.1% frequency):

- Gynaecomastia

- Impaired ability to cry

- Atrioventricular block

- Nasal dryness

- Colonic pseudo-obstruction

- Alopecia

- Hyperglycaemia

Withdrawal

Clonidine suppresses sympathetic outflow resulting in lower blood pressure, but sudden discontinuation can cause rebound hypertension due to a rebound in sympathetic outflow.[4]

Clonidine therapy should generally be gradually tapered when discontinuing therapy to avoid rebound effects from occurring. Treatment of clonidine withdrawal hypertension depends on the severity of the condition. Reintroduction of clonidine for mild cases, alpha and beta blockers for more urgent situations. Beta blockers never should be used alone to treat clonidine withdrawal as alpha vasoconstriction would still continue.[41][42]

Mechanism of action

Clonidine treats high blood pressure by stimulating α2 receptors in the brain, which decreases peripheral vascular resistance, lowering blood pressure. It has specificity towards the presynaptic α2 receptors in the vasomotor center in the brainstem. This binding decreases presynaptic calcium levels, thus inhibiting the release of norepinephrine (NE). The net effect is a decrease in sympathetic tone.[43] It has also been proposed that the antihypertensive effect of clonidine is due to agonism on the I1 receptor (imidazoline receptor), which mediates the sympatho-inhibitory actions of imidazolines to lower blood pressure.[44] Its mechanism of action in the treatment of ADHD is to increase noradrenergic tone in the prefrontal cortex (PFC) directly by binding to postsynaptic α2A adrenergic receptors and indirectly by increasing norepinephrine input from the locus coeruleus.[45]

| Receptor | Ki (nM)[46] |

|---|---|

| α1A | 316.23 |

| α1B | 316.23 |

| α1D | 125.89 |

| α2A | 42.92 |

| α2B | 106.31 |

| α2C | 233.1 |

References

- 1 2 Lowenthal, DT; Matzek, KM; MacGregor, TR (May 1988). "Clinical pharmacokinetics of clonidine.". Clinical Pharmacokinetics. 14 (5): 287–310. doi:10.2165/00003088-198814050-00002. PMID 3293868.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "clonidine (Rx) - Catapres, Catapres-TTS, more..". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 10 November 2013.

- ↑

- 1 2 Brayfield, A, ed. (13 January 2014). "Clonidine". Martindale: The Complete Drug Reference. London, UK: Pharmaceutical Press. Retrieved 28 June 2014.

- ↑ Neil, MJ (November 2011). "Clonidine: clinical pharmacology and therapeutic use in pain management.". Current Clinical Pharmacology. 6 (4): 280–7. doi:10.2174/157488411798375886. PMID 21827389.

- ↑ "FDA Approves Extended-Release Clonidine for Pediatric ADHD". WebMD LLC.

- ↑ Rossi, S, ed. (2013). Australian Medicines Handbook (2013 ed.). Adelaide: The Australian Medicines Handbook Unit Trust. ISBN 978-0-9805790-9-3.

- ↑ Palumbo, DR; Sallee, FR; Pelham WE, Jr; Bukstein, OG; Daviss, WB; McDermott, MP (February 2008). "Clonidine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: I. Efficacy and tolerability outcomes.". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 47 (2): 180–8. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31815d9af7. PMID 18182963.

- ↑ Daviss, WB; Patel, NC; Robb, AS; McDermott, MP; Bukstein, OG; Pelham WE, Jr; Palumbo, D; Harris, P; Sallee, FR (February 2008). "Clonidine for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: II. ECG changes and adverse events analysis". Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 47 (2): 189–98. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31815d9ae4. PMID 18182964.

- ↑ Kornfield R, Watson S, Higashi AS, Conti RM, Dusetzina SB, Garfield CF, Dorsey ER, Huskamp HA, Alexander GC (April 2013). "Impact of FDA Advisories on Pharmacologic Treatment of Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder". Psychiatric Services. 64 (4): 339–46. doi:10.1176/appi.ps.201200147. PMC 4023684

. PMID 23318985.

. PMID 23318985. - ↑ PALUMBO, DONNA R.; SALLEE, FLOYD R.; PELHAM, WILLIAM E.; BUKSTEIN, OSCAR G.; DAVISS, W. BURLESON; McDERMOTT, MICHAEL P. (February 2008). "Clonidine for Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder: I. Efficacy and Tolerability Outcomes". Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 47 (2): 180–188. doi:10.1097/chi.0b013e31815d9af7. PMID 18182963.

- ↑ Kollins, Scott H.; Jain, Rakesh; Brams, Matthew; Segal, Scott; Findling, Robert L.; Wigal, Sharon B.; Khayrallah, Moise (2011-06-01). "Clonidine Extended-Release Tablets as Add-on Therapy to Psychostimulants in Children and Adolescents With ADHD". Pediatrics. 127 (6): e1406–e1413. doi:10.1542/peds.2010-1260. ISSN 0031-4005. PMC 3387872

. PMID 21555501.

. PMID 21555501. - ↑ "Guanfacine, But Not Clonidine, Improves Planning and Working Memory Performance in Humans". Neuropsychopharmacology. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ↑ "Clonidine and Guanfacine IR vs ER: Old Drugs With "New" Formulations". Mental Health Clinician. Retrieved August 1, 2014.

- ↑ Egolf, A; Coffey, BJ (February 2014). "Current pharmacotherapeutic approaches for the treatment of Tourette syndrome.". Drugs of Today. 50 (2): 159–79. doi:10.1358/dot.2014.50.2.2097801. PMID 24619591.

- ↑ Fitzgerald, PJ (October 2013). "Elevated Norepinephrine may be a Unifying Etiological Factor in the Abuse of a Broad Range of Substances: Alcohol, Nicotine, Marijuana, Heroin, Cocaine, and Caffeine.". Substance Abuse. 7: 171–83. doi:10.4137/SART.S13019. PMC 3798293

. PMID 24151426.

. PMID 24151426. - ↑ Giannini, AJ (1997). Drugs of Abuse (2nd ed.). Los Angeles: Practice Management Information.

- ↑ Gourlay, SG; Stead, LF; Benowitz, NL (2004). "Clonidine for smoking cessation.". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (3): CD000058. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000058.pub2. PMID 15266422.

- ↑ Giannini, AJ; Extein, I; Gold, MS; Pottash, ALC; Castellani, S (1983). "Clonidine in mania". Drug Development Research. 3 (1): 101–105. doi:10.1002/ddr.430030112.

- ↑ van der Kolk, BA (September–October 1987). "The drug treatment of post-traumatic stress disorder.". Journal of Affective Disorders. 13 (2): 203–13. doi:10.1016/0165-0327(87)90024-3. PMID 2960712.

- ↑ Sutherland, SM; Davidson, JR (June 1994). "Pharmacotherapy for post-traumatic stress disorder.". The Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 17 (2): 409–23. PMID 7937367.

- ↑ Southwick, SM; Bremner, JD; Rasmusson, A; Morgan CA, 3rd; Arnsten, A; Charney, DS (November 1999). "Role of norepinephrine in the pathophysiology and treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder.". Biological Psychiatry. 46 (9): 1192–204. doi:10.1016/S0006-3223(99)00219-X. PMID 10560025.

- ↑ Strawn, JR; Geracioti, TD, Jr (2008). "Noradrenergic dysfunction and the psychopharmacology of posttraumatic stress disorder.". Depression and Anxiety. 25 (3): 260–71. doi:10.1002/da.20292. PMID 17354267.

- ↑ Boehnlein, JK; Kinzie, JD (March 2007). "Pharmacologic reduction of CNS noradrenergic activity in PTSD: the case for clonidine and prazosin.". Journal of Psychiatric Practice. 13 (2): 72–8. doi:10.1097/01.pra.0000265763.79753.c1. PMID 17414682.

- ↑ Huffman, JC; Stern, TA (2007). "Neuropsychiatric consequences of cardiovascular medications.". Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience. 9 (1): 29–45. PMC 3181843

. PMID 17506224.

. PMID 17506224. - ↑ Najjar, F; Weller, RA; Weisbrot, J; Weller, EB (April 2008). "Post-traumatic stress disorder and its treatment in children and adolescents.". Current Psychiatry Reports. 10 (2): 104–8. doi:10.1007/s11920-008-0019-0. PMID 18474199.

- ↑ Ziegenhorn, AA; Roepke, S; Schommer, NC; Merkl, A; Danker-Hopfe, H; Perschel, FH; Heuser, I; Anghelescu, IG; Lammers, CH (April 2009). "Clonidine improves hyperarousal in borderline personality disorder with or without comorbid posttraumatic stress disorder: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial". Journal of Clinical Psychopharmacology. 29 (2): 170–3. doi:10.1097/JCP.0b013e31819a4bae. PMID 19512980.

- ↑ Fazi, L; Jantzen, EC; Rose, JB; Kurth, CD; Watcha, MF (2001). "A comparison of oral clonidine and oral midazolam as preanesthetic medications in the pediatric tonsillectomy patient" (PDF). Anesthesia and Analgesia. 92 (1): 56–61. doi:10.1097/00000539-200101000-00011. PMID 11133600.

- ↑ Patel, SS; Dunn, CJ; Bryson, HM (1996). "Epidural clonidine: a review of its pharmacology and efficacy in the management of pain during labour and postoperative and intractable pain". CNS Drugs. 6 (6): 474–497. doi:10.2165/00023210-199606060-00007.

- ↑ Kukoyi A, Coker S, Lewis L, Nierenberg D (January 2013). "Two cases of acute dexmedetomidine withdrawal syndrome following prolonged infusion in the intensive care unit: Report of cases and review of the literature". Human and Experimental Toxicology. 32 (1): 107–110. doi:10.1177/0960327112454896. PMID 23111887. Retrieved 1 March 2013.

- ↑ Blount, BW; Pelletier, AL (2002). "Rosacea: A Common, Yet Commonly Overlooked, Condition". American Family Physician. 66 (3): 435–441. PMID 12182520.

- ↑ Campbell, CM; Kipnes, MS; Stouch, BC; Brady, KL; Kelly, M; Schmidt, WK; Petersen, KL; Rowbotham, MC; Campbell, JN (September 2012). "Randomized control trial of topical clonidine for treatment of painful diabetic neuropathy". Pain. 153 (9): 1815–1823. doi:10.1016/j.pain.2012.04.014. PMC 3413770

. PMID 22683276.

. PMID 22683276. - ↑ "Clonidine Oral Uses". WebMD.

- ↑ "Clonidine". Drugs.com.

- ↑ Fragkos, Konstantinos C.; Zárate-Lopez, Natalia; Frangos, Christos C. (2016-01-25). "What about clonidine for diarrhoea? A systematic review and meta-analysis of its effect in humans". Therapeutic Advances in Gastroenterology. 9: 1756283X15625586. doi:10.1177/1756283X15625586. ISSN 1756-283X.

- 1 2 Eisenhofer, G; Goldstein, DS; Walther, MM; et al. (2003). "Biochemical diagnosis of pheochromocytoma: how to distinguish true- from false-positive test results". Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism. 88 (6): 2656–2666. doi:10.1210/jc.2002-030005. PMID 12788870.

- 1 2 "CATAPRES® 150 TABLETS CATAPRES® AMPOULES" (PDF). TGA eBusiness Services. Boehringer Ingelheim Pty Limited. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Clonidine". Prescription Marketed Drugs. www.drugsdb.eu.

- ↑ "CATAPRES (clonidine hydrochloride) tablet [Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc.]". DailyMed. Boehringer Ingelheim Pharmaceuticals Inc. June 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ "Clonidine 25 mcg Tablets BP - Summary of Product Characteristics (SPC)". electronic Medicines Compendium. Sandoz Limited. 2 August 2012. Retrieved 27 November 2013.

- ↑ Parker, K; Brunton, L; Goodman, LS; Lazo, JS; Gilman, A (2006). Goodman & Gilman's - the pharmacological basis of therapeutics. New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 854–855. ISBN 0-07-142280-3.

- ↑ Vitiello, B. (2008). "Understanding the Risk of Using Medications for ADHD with Respect to Physical Growth and Cardiovascular Function". Child Adolesc Psychiatr Clin N Am. 17 (2): 459–474, xi. doi:10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.010. PMC 2408826

. PMID 18295156.

. PMID 18295156. - ↑ Shen, Howard (2008). Illustrated Pharmacology Memory Cards: PharMnemonics. Minireview. p. 12. ISBN 1-59541-101-1.

- ↑ Reis, D. J.; Piletz, J. E. (1997). "The imidazoline receptor in control of blood pressure by clonidine and drugs" (pdf). American Journal of Physiology. 273 (5): R1569–R1571. PMID 9374795.

- ↑ Sallee, FR (2008). "The Role of Alpha 2 Agonists in the Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder Treatment Paradigm". Medscape Reference. WebMD. Retrieved 15 November 2013.

- ↑ Roth, BL; Driscol, J (12 January 2011). "PDSP Ki Database". Psychoactive Drug Screening Program (PDSP). University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and the United States National Institute of Mental Health. Archived from the original on 8 November 2013. Retrieved 25 November 2013.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Clonidine. |

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Clonidine

- Alpha-2 agonists in ADHD