Columbia, Virginia

| Columbia, Virginia | |

|---|---|

| Unincorporated community | |

|

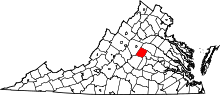

Location of Columbia, Virginia | |

| Coordinates: 37°45′8″N 78°9′44″W / 37.75222°N 78.16222°WCoordinates: 37°45′8″N 78°9′44″W / 37.75222°N 78.16222°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Virginia |

| County | Fluvanna |

| Incorporated | 1788[1] |

| Disincorporated | 2016 |

| Named for |

Columbia (poetic name for the United States)[1] |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.20 sq mi (0.53 km2) |

| • Land | 0.19 sq mi (0.50 km2) |

| • Water | 0.01 sq mi (0.03 km2) |

| Elevation | 210 ft (64 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 83 |

| • Density | 428/sq mi (165.2/km2) |

| Time zone | Eastern (EST) (UTC-5) |

| • Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) |

| ZIP code | 23038 |

| FIPS code | 51-18624[2] |

| GNIS feature ID | 1492796[3] |

Columbia, formerly known as Point of Fork, is an unincorporated community in Fluvanna County, Virginia, United States, at the confluence of the James and Rivanna rivers. Following a referendum, Columbia was dissolved as an incorporated town – until that time the smallest in Virginia – and absorbed into Fluvanna County on July 1, 2016.[4] As of the 2010 census, the town's population was 83,[5] up from 49 at the 2000 census.

Columbia is part of the Charlottesville Metropolitan Statistical Area.

History

In pre-colonial times, the Point of Fork -- near Columbia where the James and Rivanna rivers meet -- was the site of a major Monacan village of Native Americans.

During the American Revolutionary War, a Patriot arsenal under the command of Friedrich Wilhelm von Steuben stood in what was then Point of Fork. A detachment of the Queen's Rangers, composed of American Loyalists and commanded by British Colonel John Graves Simcoe, was sent to Point of Fork by Major General Charles, Earl Cornwallis to capture and confiscate the arsenal. Upon learning of Simcoe's approach, von Steuben ordered his troops to transport the arsenal's stores across the James River; heavy artillery was dumped into the river to be recovered later. Simcoe captured the arsenal on June 5, 1781, and reported seizing a vast amount of Patriot supplies. However, von Steuben and General Lafayette reported that losses were negligible.[6]

Following the end of the war and the founding of the United States, the community changed its name to "Columbia" and became incorporated as a town in 1788.[7] Columbia became a shipping point on the James River for Virginia's tobacco trade, establishing its own bateau freight line. The confluence of the rivers at Columbia linked Richmond to Lynchburg through the James River and to Charlottesville through the Rivanna.[8] In the mid-19th century, Columbia served as a point along the stagecoach route between Richmond and Staunton.[9]

The town entered an economic decline with the end of passenger railroad service in 1958, and saw many homes and businesses destroyed in floods caused by Hurricane Camille in 1969 and Hurricane Agnes in 1972. In the decades afterward, conditions in the town worsened as buildings along its main street either burned down or became abandoned. In May 2014, Columbia's mayor and town council proposed disincorporation, which if successful would result in the town being reabsorbed by Fluvanna County in exchange for financial aid.[10] Despite efforts by historic preservationists to raise money for the town's continued existence as an independent entity, residents voted to merge with the county in a referendum held on March 17, 2015. The Virginia General Assembly revoked Columbia's town charter on March 3, 2016, via HB14 during the 2016 session.[11] The disincorporation took effect on July 1, 2016.

Shrine of St. Katharine Drexel

Columbia is home to St. Joseph's Church and Shrine of St. Katharine Drexel, a parish within the Roman Catholic Diocese of Richmond.[12] The church was built by William and Catherine Wakeham, English Catholic abolitionists who moved to Columbia in 1833. Because they were abolitionists, the hill on which their house was built came to be called Free Hill. Two of the Wakehams' sons, Alfred and Richard, were Josephite Fathers, and the Wakehams built a chapel so that their sons could celebrate Mass. After Catherine Wakeham's death in 1891, the Wakeham sons' duties took them away from Columbia. An elderly African-American man, Zack Kimbro, continued to maintain the chapel and place fresh flowers and clean linen on its altar.

St. Katharine Drexel, S.B.S. (1858–1955), was an educator, a zealous opponent of racism, and founder of the Sisters of the Blessed Sacrament. She was canonized in 2000 by Pope John Paul II. She and her Sisters founded countless schools across the United States to provide educational opportunities for African-American and Native American communities, including most prominently Xavier University. In 1901 she noticed the reflection of sunlight on the chapel's cross while traveling by rail from St. Francis de Sales High School, which she had founded in Powhatan County, to Lynchburg. She inquired about the cross and was told the story of the Wakehams' chapel by Rebecca Kimbro, Zack Kimbro's daughter and a St. Francis student. St. Katharine was soon introduced to Kimbro, who told her he had prayed daily for over a decade that Mass would once more be celebrated in the chapel.

St. Katharine contacted the Josephite Fathers and arranged for Mass to be celebrated in the chapel regularly. She also founded a small school which was built adjacent to the chapel and was one of Fluvanna County's only educational opportunities for African-American children. St. Joseph's and its school became the center of one of Virginia's only historically African-American Catholic communities.

Because of its location on high ground, St. Joseph's was spared during the series of 20th century floods that mostly destroyed Columbia's other buildings. St. Joseph's and the Shrine of St. Katharine Drexel is still an active parish, sharing a pastor with Saints Peter and Paul Catholic Church in Palmyra. St. Joseph's also serves Catholic students at the nearby Fork Union Military Academy.[13]

Geography

Columbia is located in the southeast corner of Fluvanna County at 37°45′8″N 78°9′44″W / 37.75222°N 78.16222°W (37.752206, −78.162291),[14] on the north side of the James and Fluvanna rivers. Virginia State Route 6 passes through the town, leading northwest 4.5 miles (7.2 km) to U.S. Route 15 at Dixie and east 16 miles (26 km) to Goochland. Charlottesville is 31 miles (50 km) to the northwest, and Richmond is 47 miles (76 km) to the east.

According to the United States Census Bureau, the former town limits encompassed a total area of 0.19 square miles (0.5 km2), of which 0.01 square miles (0.02 km2), or 4.90%, is water.[5]

Climate

Climate is characterized by relatively high temperatures and evenly distributed precipitation throughout the year. The Köppen Climate Classification subtype for this climate is "Cfa" (Humid Subtropical Climate).[15]

| Climate data for Columbia, Virginia | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 8 (46) |

9 (48) |

14 (57) |

20 (68) |

25 (77) |

29 (84) |

31 (87) |

30 (86) |

27 (80) |

21 (69) |

15 (59) |

9 (48) |

19 (66) |

| Average low °C (°F) | −4 (24) |

−3 (26) |

0 (32) |

5 (41) |

10 (50) |

15 (59) |

18 (64) |

17 (62) |

13 (55) |

6 (42) |

1 (33) |

−3 (26) |

6 (42) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 81 (3.2) |

71 (2.8) |

91 (3.6) |

84 (3.3) |

94 (3.7) |

91 (3.6) |

109 (4.3) |

107 (4.2) |

84 (3.3) |

84 (3.3) |

71 (2.8) |

79 (3.1) |

1,046 (41.2) |

| Source: Weatherbase [16] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1860 | 263 | — | |

| 1870 | 311 | 18.3% | |

| 1880 | 239 | −23.2% | |

| 1890 | 239 | 0.0% | |

| 1900 | 216 | −9.6% | |

| 1910 | 157 | −27.3% | |

| 1920 | 185 | 17.8% | |

| 1930 | 154 | −16.8% | |

| 1940 | 144 | −6.5% | |

| 1950 | 119 | −17.4% | |

| 1960 | 86 | −27.7% | |

| 1970 | 125 | 45.3% | |

| 1980 | 111 | −11.2% | |

| 1990 | 58 | −47.7% | |

| 2000 | 49 | −15.5% | |

| 2010 | 83 | 69.4% | |

| Est. 2015 | 80 | [17] | −3.6% |

As of the census[2] of 2010, there were 83 people, 27 households, and 19 families residing in the town. The racial makeup of the town was 53% White and 47% African American. No other races, or multi-racial individuals, were listed among the population.

There were 27 households out of which 40.7% had children under the age of 18 living with them, and 22.2% had individuals 65 years and older. 40.7% were married couples living together, 25.9% had a female householder with no husband present, 1 household (3.7) was a male with no wife present, and 29.6% were non-families. 14.8% of all households were made up of individuals and 3.7% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 3.07 and the average family size was 3.47.

In the town the population was spread out with 26.5% under the age of 20, 8.4% from 21 to 24, 33.7% from 25 to 44, 21.7% from 45 to 64, and 9.6% who were 65 years of age or older. The oldest resident was a female in the 80–84 age group. The median age was 34.5 years. There were a total of 41 males and 42 females.

Approximately 55.6% of the population aged 16 and older were employed. The median household income was $90,000, and the median family income was $43,750. The per capita income for the town was $14,956. 45.5% of all families were below the poverty line. while 100% of the families headed by a female with no husband present were below the poverty line.[19][20]

References

- 1 2 Cox, Edwin (1965). Gleanings of Fluvanna History. Fluvanna County Historical Society. pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Archived from the original on September 11, 2013. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey. October 25, 2007. Retrieved January 31, 2008.

- ↑ Fluvanna County Town of Columbia to Dissolve, WVIR-TV, 29 June 2016

- 1 2 "Geographic Identifiers: 2010 Demographic Profile Data (G001): Columbia town, Virginia". U.S. Census Bureau, American Factfinder. Retrieved October 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Fluvanna and the American Revolution", Fluvanna Chamber of Commerce, Retrieved 5 July 2016

- ↑ Strong, Ted (March 17, 2015). "Columbia Residents Vote 18–1 to Do Away with Town". Richmond Times-Dispatch.

- ↑ Justin Bergman, "Columbia: Will Fluvanna's historic burg be saved?", The Hook, 18 December 2002

- ↑ Smith, John Calvin (1847). The Illustrated Hand-book, a New Guide for travelers through the United States of America. New York City: Sherman & Smith. p. 132.

- ↑ Lynn Stayton-Eurell. "Fluvanna Review – Mayor, town council seek to dissolve town of Columbia". fluvannareview.com. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Legislative Information System". Retrieved July 3, 2016.

- ↑ "Saint Joseph's Shrine of St. Katharine Drexel – Catholic Diocese of Richmond". richmonddiocese.org. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ↑ Carlos M. Santos. "Fluvanna Review – Saved by a saint and steeped in history, a Columbia church thrives". fluvannareview.com. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- ↑ "Columbia, Virginia Köppen Climate Classification (Weatherbase)". Weatherbase. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ↑ "Weatherbase.com". Weatherbase. 2013. Retrieved on August 20, 2013.

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder – Results". census.gov. Retrieved September 13, 2015.

- ↑ Data Access and Dissemination Systems (DADS). "American FactFinder – Results". census.gov. Retrieved September 13, 2015.