Fort Jones, California

| Fort Jones, California | |

|---|---|

| City | |

| City of Fort Jones | |

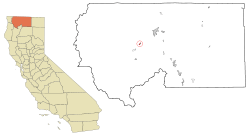

Location in Siskiyou County and the U.S. state of California | |

Fort Jones, California Location in the United States | |

| Coordinates: 41°36′26″N 122°50′31″W / 41.60722°N 122.84194°WCoordinates: 41°36′26″N 122°50′31″W / 41.60722°N 122.84194°W | |

| Country |

|

| State |

|

| County |

|

| Incorporated | March 16, 1872[1] |

| Area[2] | |

| • Total | 0.602 sq mi (1.560 km2) |

| • Land | 0.602 sq mi (1.560 km2) |

| • Water | 0 sq mi (0 km2) 0% |

| Elevation[3] | 2,759 ft (841 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 839 |

| • Density | 1,400/sq mi (540/km2) |

| Time zone | Pacific (PST) (UTC-8) |

| • Summer (DST) | PDT (UTC-7) |

| ZIP code | 96032 |

| Area code(s) | 530 |

| FIPS code | 06-25128 |

| GNIS feature ID | 277519, 2410527 |

| Reference no. | 317[4] |

Fort Jones is a city in the Scott Valley area of Siskiyou County, California, United States. The population was 839 at the 2010 census, up from 600 as of the 2000 census.

History

Scottsburg, Scottsville, Wheelock, Ottitiewa and Fort Jones

Fort Jones is registered as a California Historical Landmark.[4] It takes its name from the frontier outpost once located less than a mile to the south of the city's corporate limits. The town was originally named Scottsburg (ca. 1850), but was changed to Scottsville shortly afterward. In 1852, the site was again renamed Wheelock, this time in honor of Mr. O. C. Wheelock who, with his partners, established the area's first commercial enterprise. In 1854, a post office was established and the town was renamed again, becoming known as Ottitiewa, the Indian name for the Scott River branch of the Shasta tribe. The name remained unchanged until 1860 when local citizens successfully petitioned the postal department to change the name to Fort Jones, a name that is retained to the present day.[5]

The earliest permanent building at the town site was built in 1851 by two Messrs. Brown and Kelly. It was purchased soon after construction by O. C. Wheelock, Captain John B. Pierce, and two other unknown partners. Wheelock and his partners established a trading post, a bar, and a brothel at this site, which primarily served the troopers stationed at the fort. Near the end of the 1850s, the nearby mining camps of Hooperville and Deadwood began to disband as a result of the dwindling stores of placer gold, epidemic illness and devastating fires.

The mines around Scott Valley attracted many immigrants from many parts of the United States and the world, attracted to the area by news of the California Gold Rush of the 1850s. Irish and Portuguese immigrants remained as ranchers in the area after making enough on the gold fields to purchase property tracts in the valley. In the early years of the Twentieth Century, the northern Scott River tributaries of Moffitt and McAddams creeks were extensively settled by the Portuguese. The Irish surname Marlahan lives on after that family received a shipment of British hay seed infected with the seed of a plant known as Dyers Woad.[6] Those seeds spread their spawn throughout Scott Valley, culturing a plant known in the area as Marlahan Mustard. The plant has a beautiful, canary plume in the spring which matures to small, black, hard seeds. Unfortunately, the herbivore beasts of burden will not eat hay in which this plant exists, and ever since it has been a scourge on the ranchers of Scott Valley.

On December 14, 1894, Billy Dean, a Native American accused of shooting co-worker William Baremore near Grinder Creek outside of Happy Camp, California on December 5, 1894 was lynched by unknown persons while in the custody of Constable Fred Dixon. Constable Dixon and Dean were staying at a hotel in Happy Camp while on their way the Yreka, California jail, where Dean would be safe from vigilantes in Happy Camp. Baremore’s friends were tailing the pair and waited for their moment. At two in the morning on December 14, 1894, a dozen masked men stormed the room and disarmed Constable Dixon. They tied Dean’s hands and carried him to the Wheeler Building which was under construction where they strung him up by the neck from a derrick. His body was left hanging until 11:00 a.m. That day’s headlines in the Scott Valley News boasted, "He Is Now A Good Indian. Billy Dean Kills a White Man Without Cause and Is Summarily Hoisted to the Happy Hunting Ground."[7]

Fort Jones

Located at 41°35′46″N 122°50′31″W / 41.59611°N 122.84194°W, the post of Fort Jones was established on October 18, 1852, by its first commandant, Captain (brevet Major) Edward H. Fitzgerald, E Company, 1st U.S. Dragoons. Fort Jones was named in honor of Colonel Roger Jones, who had been the Adjutant General of the Army from March 1825 to July 1852.[8]

Such military posts were to be established in the vicinity of major stage routes, which would have meant locating the post in the vicinity of Yreka, sixteen miles to the Northeast.[8] The areas around Yreka did not contain sufficient resources, including forage for their animals, so Capt. Fitzgerald located his troop some sixteen miles to the southwest, in what was then known as Beaver Valley.[8] Fort Jones would continue to serve Siskiyou County's military needs until the order was received to evacuate some six years later on June 23, 1858.[8]

Among the officers stationed at Fort Jones who would attain national prominence in ensuing years were Phil Sheridan (Union Army); William Wing Loring (Confederate); John B. Hood (Confederate); George Crook (Union), who would become one of the greatest leaders of the Grand Army of the Republic less than a decade later; and George Pickett (Confederate). Ulysses S. Grant later a (Union) commander was ordered to Fort Jones, but was Absent Without Leave for whatever his tenure would have been.

Geography

Fort Jones is located at 41°36′26″N 122°50′31″W / 41.60722°N 122.84194°W (41.607303, -122.841817).[9]

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 0.6 square miles (1.6 km2), all of it land.

Climate

This region experiences warm (but not hot) and dry summers, with no average monthly temperatures above 71.6 °F. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Fort Jones has a warm-summer Mediterranean climate, abbreviated "Csb" on climate maps.[10]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 266 | — | |

| 1900 | 356 | 33.8% | |

| 1910 | 316 | −11.2% | |

| 1920 | 331 | 4.7% | |

| 1930 | 302 | −8.8% | |

| 1940 | 360 | 19.2% | |

| 1950 | 525 | 45.8% | |

| 1960 | 483 | −8.0% | |

| 1970 | 515 | 6.6% | |

| 1980 | 544 | 5.6% | |

| 1990 | 639 | 17.5% | |

| 2000 | 660 | 3.3% | |

| 2010 | 839 | 27.1% | |

| Est. 2015 | 688 | [11] | −18.0% |

2010

The 2010 United States Census[13] reported that Fort Jones had a population of 839. The population density was 1,393.1 people per square mile (537.9/km²). The racial makeup of Fort Jones was 650 (77.5%) White, 33 (3.9%) African American, 61 (7.3%) Native American, 8 (1.0%) Asian, 0 (0.0%) Pacific Islander, 23 (2.7%) from other races, and 64 (7.6%) from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 103 persons (12.3%).

The Census reported that 710 people (84.6% of the population) lived in households, 0 (0%) lived in non-institutionalized group quarters, and 129 (15.4%) were institutionalized.

There were 304 households, out of which 88 (28.9%) had children under the age of 18 living in them, 130 (42.8%) were opposite-sex married couples living together, 30 (9.9%) had a female householder with no husband present, 23 (7.6%) had a male householder with no wife present. There were 32 (10.5%) unmarried opposite-sex partnerships, and 0 (0%) same-sex married couples or partnerships. 94 households (30.9%) were made up of individuals and 34 (11.2%) had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.34. There were 183 families (60.2% of all households); the average family size was 2.91.

The population was spread out with 168 people (20.0%) under the age of 18, 65 people (7.7%) aged 18 to 24, 266 people (31.7%) aged 25 to 44, 230 people (27.4%) aged 45 to 64, and 110 people (13.1%) who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 39.1 years. For every 100 females there were 136.3 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 146.7 males.

There were 344 housing units at an average density of 571.2 per square mile (220.5/km²), of which 182 (59.9%) were owner-occupied, and 122 (40.1%) were occupied by renters. The homeowner vacancy rate was 2.7%; the rental vacancy rate was 5.4%. 426 people (50.8% of the population) lived in owner-occupied housing units and 284 people (33.8%) lived in rental housing units.

2000

As of the census[14] of 2000, there were 660 people, 298 households, and 185 families residing in the city. The population density was 1,096.7 people per square mile (424.7/km²). There were 328 housing units at an average density of 545.0 per square mile (211.1/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 88.64% White, 0.15% African American, 3.18% Native American, 0.45% Pacific Islander, 1.52% from other races, and 6.06% from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 8.03% of the population.

There were 298 households out of which 28.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 44.6% were married couples living together, 12.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 37.6% were non-families. 33.6% of all households were made up of individuals and 17.8% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.21 and the average family size was 2.81.

In the city the population was spread out with 23.6% under the age of 18, 6.8% from 18 to 24, 23.3% from 25 to 44, 24.1% from 45 to 64, and 22.1% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 43 years. For every 100 females there were 89.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.1 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $21,563, and the median income for a family was $25,625. Males had a median income of $31,058 versus $16,875 for females. The per capita income for the city was $15,301. About 23.3% of families and 26.0% of the population were below the poverty line, including 31.1% of those under age 18 and 14.5% of those age 65 or over.

Politics

In the state legislature Fort Jones is in the 1st Senate District, represented by Republican Ted Gaines,[15] and the 1st Assembly District, represented by Republican Brian Dahle.[16]

Federally, Fort Jones is in California's 1st congressional district, represented by Republican Doug LaMalfa.[17]

Notable people

- Norman F. Cardoza, (September 3, 1930 - ) a journalist at the Reno Evening Gazette and Nevada State Journal, earned the Pulitzer Prize "for editorials challenging the power of a local brothel keeper". He was born in Yreka, California, son of John C. and Emily S. Cardoza, and attended Moffett Creek School and Fort Jones High School.[18]

- Lauran Paine, born Lawrence Kerfman Duby Jr., (February 25, 1916 – December 1, 2001) authored more than 1000 books[19] including hundreds of Western stories under various pseudonyms,[20] including Mark Carrel, Clay Allen, A. A. Andrews, Dennis Archer, John Armour, Carter Ashby, Harry Beck, Will Benton, Frank Bosworth, Concho Bradley, Claude Cassady, Clint Custer, James Glenn, Will Houston, Troy Howard, Cliff Ketchum, Clint O'Conner, Jim Slaughter and Buck Standish among others.[21] He was a long-term resident of Fort Jones.[22] At least one of his stories was made into a motion picture.[22]

- John King Luttrell (June 27, 1831 – October 4, 1893) was a U.S. Representative from California. He moved to Siskiyou County in 1858 and purchased a ranch near Fort Jones. He engaged in agricultural pursuits, mining, and the practice of law. He was appointed United States Commissioner of Fisheries and special agent of the United States Treasury for Alaska in 1893. He died in Sitka, Alaska at age 62, and was interred in Fort Jones Cemetery.[23]

See also

References

- ↑ "California Cities by Incorporation Date" (Word). California Association of Local Agency Formation Commissions. Retrieved August 25, 2014.

- ↑ "2010 Census U.S. Gazetteer Files – Places – California". United States Census Bureau.

- ↑ "Fort Jones". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved November 2, 2014.

- 1 2 "Fort Jones". Office of Historic Preservation, California State Parks. Retrieved 2012-10-14.

- ↑ Frickstad, Walter N., A Century of California Post Offices 1848-1954, Philatelic Research Society, Oakland, CA. 1955, pp.184-193.

- ↑ Ed Marlahan, 1965

- ↑ Kulczyk,David. (2008). California Justice: Shootouts, Lynching and Assassinations in the Golden State. Word Dancer Press. P58 ISBN 1-884995-54-3

- 1 2 3 4 The California State Military Museum, Historic California Posts: Fort Jones (Siskiyou County)

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. 2011-02-12. Retrieved 2011-04-23.

- ↑ Climate Summary for Fort Jones, California

- ↑ "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population for Incorporated Places: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Census of Population and Housing". Census.gov. Retrieved June 4, 2015.

- ↑ "2010 Census Interactive Population Search: CA - Fort Jones city". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved July 12, 2014.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "Senators". State of California. Retrieved March 10, 2013.

- ↑ "Members Assembly". State of California. Retrieved March 2, 2013.

- ↑ "California's 1st Congressional District - Representatives & District Map". Civic Impulse, LLC. Retrieved March 1, 2013.

- ↑ Heinz-Dietrich Fischer; Erika J. Fischer (1990). The Pulitzer Prize Archive: Political editorial, 1916-1988. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 295–. ISBN 978-3-598-30174-2.

- ↑ Ouse, David (September 16, 2013). "Forgotten Duluthian Lauran Paine". Zenith City Online, Duluth Minnesota. Retrieved January 1, 2013.

- ↑ Paul Varner (September 20, 2010). Historical Dictionary of Westerns in Literature. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7486-2.

- ↑ Whitehead, David, Lauran Paine, Keith Chapman's Black Horse Extra

- 1 2 Bernita Tickner; Gail Fiorini-Jenner (March 1, 2006). The State of Jefferson. Arcadia Publishing. pp. 90–. ISBN 978-0-7385-3096-3.

- ↑

- United States Congress. "Fort Jones, California (id: L000522)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress.

Additional reading

- Lauran Paine, ed., Preface and The Fort and Its Dependencies, The Siskiyou Pioneer, Vol. III, No. 3. Yreka, CA: Siskiyou County Historical Society, 1960.

- Michael Hendryx; Orsola Silva; Richard Silva; Siskiyou County Historical Society (2003). Historic Look at Scott Valley. Siskiyou County Historical Society.

- Gary D. Stumpf (1979). Gold mining in Siskiyou County, 1850-1900. Siskiyou County Historical Society.