Bear

| Bears Temporal range: 38–0 Ma Late Eocene – Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Captive brown bear at the Polar Zoo. | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Caniformia |

| Infraorder: | Arctoidea |

| Family: | Ursidae G. Fischer de Waldheim, 1817 |

| Subfamilies | |

|

†Amphicynodontinae | |

Bears are mammals of the family Ursidae. Bears are classified as caniforms, or doglike carnivorans, with the pinnipeds being their closest living relatives. Although only eight species of bears are extant, they are widespread, appearing in a wide variety of habitats throughout the Northern Hemisphere and partially in the Southern Hemisphere. Bears are found on the continents of North America, South America, Europe, and Asia.

Common characteristics of modern bears include large bodies with stocky legs, long snouts, shaggy hair, plantigrade paws with five nonretractile claws, and short tails. While the polar bear is mostly carnivorous, and the giant panda feeds almost entirely on bamboo, the remaining six species are omnivorous with varied diets.

With the exception of courting individuals and mothers with their young, bears are typically solitary animals. They are generally diurnal, but may be active during the night (nocturnal) or twilight (crepuscular), particularly around humans. Bears possess an excellent sense of smell and, despite their heavy build and awkward gait, are adept runners, climbers, and swimmers. Bears use shelters, such as caves and burrows, as their dens; most species occupy their dens during the winter for a long period (up to 100 days) of sleep similar to hibernation.[1]

Bears have been hunted since prehistoric times for their meat and fur. With their tremendous physical presence and charisma, they play a prominent role in the arts, mythology, and other cultural aspects of various human societies. In modern times, the bears' existence has been pressured through the encroachment on their habitats and the illegal trade of bears and bear parts, including the Asian bile bear market. The IUCN lists six bear species as vulnerable or endangered, and even least concern species, such as the brown bear, are at risk of extirpation in certain countries. The poaching and international trade of these most threatened populations are prohibited, but still ongoing.

Etymology

The English word "bear" comes from Old English bera and belongs to a family of names for the bear in Germanic languages that originate from an adjective meaning "brown".[2] In Scandinavia, the word for bear is björn (or bjørn), and is a relatively common given name for males. The use of this name is ancient and has been found mentioned in several runestone inscriptions.[3]

The reconstructed Proto-Indo-European name of the bear is *h₂ŕ̥tḱos, whence Sanskrit ṛ́kṣa, Avestan arša, Greek ἄρκτος (arktos), Latin ursus, Welsh arth (whence perhaps "Arthur"), Albanian ari, Armenian արջ (arj). Also compared is Hittite ḫartagga-, the name of a monster or predator.[2] In the binomial name of the brown bear, Ursus arctos, Linnaeus simply combined the Latin and Greek names.

The Proto-Indo-European (PIE) word for bear, *h₂ŕ̥tḱos seems to have been subject to taboo deformation or replacement in some languages (as was the word for wolf, wlkwos), resulting in the use of numerous unrelated words with meanings like "brown one" (English bruin) and "honey-eater" (Slavic medved).[4] Thus, some Indo-European language groups do not share the same PIE root.

Evolutionary history

The family Ursidae is one of nine families in the suborder Caniformia, or "doglike" carnivores, within the order Carnivora. Bears' closest living relatives are the pinnipeds, canids, and musteloids.[5]

The following synapomorphic (derived) traits set bears apart from related families:

- presence of an alisphenoid canal

- paroccipital processes that are large and not fused to the auditory bullae

- auditory bullae are not enlarged

- lacrimal bone is vestigial

- cheek teeth are bunodont and hence indicative of a broad, hypocarnivorous (not strictly meat-eating) diet (although hypercarnivorous (strictly meat-eating) taxa are known from the fossil record)[6]

- carnassials are flattened

Additionally, members of this family possess posteriorly oriented M2 postprotocrista molars, elongated m2 molars, and a reduction of the premolars.

Modern bears comprise eight species in three subfamilies: Ailuropodinae (monotypic with the giant panda), Tremarctinae (monotypic with the spectacled bear), and Ursinae (containing six species divided into one to three genera, depending on the authority).

Fossil bears

The earliest members of Ursidae belong to the extinct subfamily Amphicynodontinae, including Parictis (late Eocene to early middle Miocene, 38–18 Mya) and the slightly younger Allocyon (early Oligocene, 34–30 Mya), both from North America. These animals looked very different from today's bears, being small and raccoon-like in overall appearance, and diets perhaps more similar to that of a badger. Parictis does not appear in Eurasia and Africa until the Miocene.[7] It is unclear whether late-Eocene ursids were also present in Eurasia, although faunal exchange across the Bering land bridge may have been possible during a major sea level low stand as early as the late Eocene (about 37 Mya) and continuing into the early Oligocene.[8] European genera morphologically are very similar to Allocyon, and also the much younger American Kolponomos (about 18 Mya), are known from the Oligocene, including Amphicticeps and Amphicynodon.

The raccoon-sized, dog-like Cephalogale is the oldest-known member of the subfamily Hemicyoninae, which first appeared during the middle Oligocene in Eurasia about 30 Mya ago. The subfamily also includes the younger genera Phoberocyon (20–15 Mya), and Plithocyon (15–7 Mya).

A Cephalogale-like species gave rise to the genus Ursavus during the early Oligocene (30–28 Mya); this genus proliferated into many species in Asia and is ancestral to all living bears. Species of Ursavus subsequently entered North America, together with Amphicynodon and Cephalogale, during the early Miocene (21–18 Mya).

Members of the living lineages of bears diverged from Ursavus between 15 and 20 Mya ago,[9][10] likely via the species Ursavus elmensis. Based on genetic and morphological data, the Ailuropodinae (pandas) were the first to diverge from other living bears about 19 Mya ago, although no fossils of this group have been found before about 5 Mya.[11]

The New World short-faced bears (Tremarctinae) differentiated from Ursinae following a dispersal event into North America during the mid-Miocene (about 13 Mya).[11] They invaded South America (~1 Ma) following formation of the Isthmus of Panama.[12] Their earliest fossil representative is Plionarctos in North America (~ 10–2 Ma). This genus is probably the direct ancestor to the North American short-faced bears (genus Arctodus), the South American short-faced bears (Arctotherium), and the spectacled bears, Tremarctos, represented by both an extinct North American species (T. floridanus), and the lone surviving representative of the Tremarctinae, the South American spectacled bear (T. ornatus).

The subfamily Ursinae experienced a dramatic proliferation of taxa about 5.3–4.5 Mya ago, coincident with major environmental changes; with the first members of the genus Ursus also appearing around this time.[11] The sloth bear is a modern survivor of one of the earliest lineages to diverge during this radiation event (5.3 Mya); it took on its peculiar morphology, related to its diet of termites and ants, no later than by the early Pleistocene. By 3–4 Mya ago, the species Ursus minimus appears in the fossil record of Europe; apart from its size, it was nearly identical to today's Asiatic black bear. It is likely ancestral to all bears within Ursinae, perhaps aside from the sloth bear. Two lineages evolved from U. minimus: the black bears (including the sun bear, the Asiatic black bear, and the American black bear); and the brown bears (which includes the polar bear). Modern brown bears evolved from U. minimus via Ursus etruscus, which itself is ancestral to both the extinct Pleistocene cave bear and today's brown and polar bears. Species of Ursinae have migrated repeatedly into North America from Eurasia as early as 4 Mya during the early Pliocene.[13]

The fossil record of bears is exceptionally good. Direct ancestor-descendent relationships between individual species are often fairly well established, with sufficient intermediate forms known to make the precise cut-off between an ancestral and its daughter species subjective.[14]

Other extinct bear genera include Agriarctos, Indarctos, and Agriotherium (sometimes placed within hemicyonids).

Taxonomic revisions of living bear species

The giant panda's taxonomy (subfamily Ailuropodinae) has long been debated. Its original classification by Armand David in 1869 was within the bear genus Ursus, but, in 1870, it was reclassified by Alphonse Milne-Edwards to the raccoon family.[15] In recent studies, the majority of DNA analyses suggest that the giant panda has a much closer relationship to other bears and should be considered a member of the family Ursidae.[16] Estimates of divergence dates place the giant panda as the most ancient offshoot among living taxa within Ursidae, having split from other bears as recently as 11.6 Mya to as distantly as 22.1 Mya.[11][17] The red panda was included within Ursidae in the past. However, more recent research does not support such a conclusion, and instead places it in its own family Ailuridae, in superfamily Musteloidea along with Mustelidae, Procyonidae, and Mephitidae.[18][19][20] Multiple similarities between the two pandas, including the presence of false thumbs, are thus thought to represent an example of convergent evolution for feeding primarily on bamboo.

The mitochondrial DNA of brown bears of Alaska's ABC Islands is more closely related to polar bears than to brown bears elsewhere in the world.[21] This is because of repeated historical interbreeding between polar bears and brown bears on the islands.[22] Also, the very rare Tibetan blue bear is a type of brown bear. Koalas are often referred to as bears due to their appearance; however, they are marsupials, not bears.

Classification

(Extant species in bold, extinct taxa marked with †.)

- Family Ursidae

- Subfamily Ailuropodinae

- † Ailurarctos

- † Ailurarctos lufengensis

- † Ailurarctos yuanmouenensis

- Ailuropoda (pandas)

- † Ailuropoda baconi

- † Ailuropoda fovealis

- Ailuropoda melanoleuca – giant panda

- Ailuropoda melanoleuca melanoleuca; giant panda

- Ailuropoda melanoleuca qinlingensis; Qinling panda

- † Ailuropoda microta

- † Ailuropoda wulingshanensis

- † Kretzoiarctos

- † Ailurarctos

- Subfamily Tremarctinae

- † Plionarctos

- † Plionarctos edensis

- † Plionarctos harroldorum

- Tremarctos (spectacled bears)

- Tremarctos ornatus – spectacled bear

- † Tremarctos floridanus – Florida spectacled bear

- † Arctodus

- † Arctodus simus – giant short-faced bear

- † Arctodus pristinus

- † Arctotherium

- † Arctotherium angustidens

- † Arctotherium bonariense

- † Arctotherium brasilense

- † Arctotherium latidens

- † Arctotherium tarijense

- † Arctotherium vetustum

- † Arctotherium wingei

- † Plionarctos

- Subfamily Ursinae

- † Ursavus

- † Ursavus brevirhinus

- † Ursavus depereti

- † Ursavus elmensis

- † Ursavus pawniensis

- † Ursavus primaevus

- † Ursavus tedfordi

- † Indarctos

- † Indarctos anthraciti

- † Indarctos arctoides

- † Indarctos atticus

- † Indarctos nevadensis

- † Indarctos oregonensis

- † Indarctos salmontanus

- † Indarctos vireti

- † Indarctos zdanskyi

- † Agriotherium

- † Agriotherium inexpetans

- † Agriotherium schneideri

- † Agriotherium sivalensis

- Melursus

- Melursus ursinus – sloth bear

- Melursus ursinus inornatus; Sri Lankan sloth bear

- Melursus ursinus ursinus; Indian sloth bear

- Melursus ursinus – sloth bear

- Helarctos

- Helarctos malayanus – sun bear

- Helarctos malayanus malayanus

- Helarctos malayanus euryspilus; Borneo sun bear

- Helarctos malayanus – sun bear

- Ursus

- † Ursus rossicus

- † Ursus sackdillingensis

- † Ursus minimus

- Ursus thibetanus – Asian black bear

- Ursus thibetanus formosanus; Formosan black bear

- Ursus thibetanus gedrosianus

- Ursus thibetanus japonicus; Japanese black bear

- Ursus thibetanus laniger

- Ursus thibetanus mupinensis

- Ursus thibetanus thibetanus

- Ursus thibetanus ussuricus; Manchurian black bear or Ussuri black bear

- † Ursus abstrusus

- Ursus americanus – American black bear

- Ursus americanus altifrontalis, Olympic black bear

- Ursus americanus amblyceps, New Mexico black bear

- Ursus americanus americanus, eastern black bear

- Ursus americanus californiensis, California black bear

- Ursus americanus carlottae, Haida Gwaii black bear or Queen Charlotte black bear

- Ursus americanus cinnamomum, cinnamon bear

- Ursus americanus emmonsii, glacier bear

- Ursus americanus eremicus, Mexican black bear

- Ursus americanus floridanus, Florida black bear

- Ursus americanus hamiltoni, Newfoundland black bear

- Ursus americanus kermodei, Kermode bear or spirit bear

- Ursus americanus luteolus, Louisiana black bear

- Ursus americanus machetes, West Mexico black bear

- Ursus americanus perniger, Kenai black bear

- Ursus americanus pugnax, Dall black bear

- Ursus americanus vancouveri, Vancouver Island black bear

- † Ursus etruscus

- Ursus arctos – brown bear

- Ursus arctos arctos; Eurasian brown bear

- Ursus arctos alascensis

- Ursus arctos beringianus; Kamchatka brown bear or Far Eastern brown bear

- † Ursus arctos californicus; California golden bear

- † Ursus arctos crowtheri; Atlas bear

- † Ursus arctos dalli

- Ursus arctos gobiensis; Gobi bear (very rare)

- Ursus arctos horribilis; grizzly bear, North American brown bear, or silvertip bear

- Ursus arctos isabellinus; Himalayan brown bear or Himalayan red bear

- Ursus arctos lasiotus; Ussuri brown bear or black grizzly

- Ursus arctos middendorffi; Kodiak bear

- † Ursus arctos nelsoni; Mexican grizzly bear

- Ursus arctos piscator; Bergman's bear (extinct?)

- Ursus arctos pruinosus; Tibetan blue bear, Tibetan bear, or Himalayan blue bear

- Ursus arctos sitkensis

- Ursus arctos syriacus; Syrian (brown) bear

- Ursus maritimus – polar bear

- Ursus maritimus maritimus

- † Ursus maritimus tyrannus (possibly a brown bear)

- † Ursus savini

- † Ursus deningeri

- † Ursus spelaeus – cave bear

- † Ursus inopinatus, MacFarlane's bear (cryptid; possibly a hybrid)

- † Ursavus

- † Kolponomos

- † Kolponomos clallamensis

- † Kolponomos newportensis

- Subfamily Ailuropodinae

The genera Melursus and Helarctos are sometimes also included in Ursus. The Asiatic black bear and the polar bear used to be placed in their own genera, Selenarctos and Thalarctos; these names have since been reduced in rank to subgeneric rank.

A number of hybrids have been bred between American black, brown, and polar bears.

Biology

Morphology

Bears are generally bulky and robust animals with relatively short legs. They are sexually dimorphic with regard to size, with the males being larger.[23][24] Larger species tend to show increased levels of sexual dimorphism in comparison to smaller species,[24] and where a species varies in size across its distribution, individuals from larger-sized areas tend also to vary more. Bears include the most massive terrestrial members of the order Carnivora. Some exceptional polar bears and Kodiak bears (a brown bear subspecies) have been weighed at 1,002 kg (2,209 lb) and 751 kg (1,656 lb) respectively.[25] As to which species is the largest depends on whether the assessment is based on which species has the largest individuals (brown bears) or on the largest average size (polar bears), as some races of brown bears are much smaller than polar bears. Adult male Kodiak bears average 480 to 533 kg (1,058 to 1,175 lb) compared to an average of 386 to 408 kg (851 to 899 lb) in adult male polar bears, per the Guinness Book of World Records.[25] The smallest bears are the sun bears of Asia, which weigh an average of 65 kg (143 lb) for the males and 45 kg (99 lb) for the females, though the smallest mature females can weigh only 20 kg (44 lb).[26][27] All "medium"-sized bear species (which include the other five extant species) are around the same average weight, with males averaging around 100 to 120 kg (220 to 260 lb) and females averaging around 60 to 85 kg (132 to 187 lb), although it is not uncommon for male American black bears to considerably exceed "average" weights.[28] Head-and-body length can range from 120 cm (47 in) in sun bears to 300 cm (120 in) in large polar and brown bears and shoulder height can range from 60 cm (24 in) to over 160 cm (63 in) in the same species, respectively. The tails of bears are often considered a vestigial feature and can range from 3 to 22 cm (1.2 to 8.7 in).[27][28]

Unlike most other land carnivorans, bears are plantigrade. They distribute their weight toward the hind feet, which makes them look lumbering when they walk. They are still quite fast, with the brown bear reaching 48 km/h (30 mph), although they are still slower than felines and canines. Bears can stand on their hind feet and sit up straight with remarkable balance. Bears' nonretractable claws are used for digging, climbing, tearing, and catching prey. Their ears are rounded.

Bears have an excellent sense of smell, better than the dogs (Canidae), or possibly any other mammal. This sense of smell is used for signalling between bears (either to warn off rivals or detect mates) and for finding food. Smell is the principal sense used by bears to find most of their food.[26]

Dentition

Unlike most other members of the Carnivora, bears have relatively undeveloped carnassial teeth, and their teeth are adapted for a diet that includes a significant amount of vegetable matter. The canine teeth are large, and the molar teeth flat and crushing. Considerable variation occurs in dental formula even within a given species. This may indicate bears are still in the process of evolving from carnivorous to predominantly herbivorous diets. Polar bears appear to have secondarily re-evolved carnassial-like cheek teeth, as their diets have switched back towards carnivory.[29] The dental formula for living bears is: 3.1.2–4.23.1.2–4.3

Distribution and habitat

Bears are primarily found in the Northern Hemisphere, and with one exception, only in Asia, North America, and Europe. The single exception is the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus); native to South America it inhabits the Andean region. The Atlas bear, a subspecies of the brown bear, was the only bear native to Africa. It was distributed in North Africa from Morocco to Libya, but has been extinct since around the 1870s. The most widespread species is the brown bear, which occurs from Western Europe eastwards through Asia to the western areas of North America. The American black bear is restricted to North America, and the polar bear is restricted to the Arctic Sea. All the remaining species are Asian.[26]

With the exception of the polar bear, bears are mostly forest species. Some species, particularly the brown bear, may inhabit or seasonally use other areas, such as alpine scrub or tundra.

Behaviour

Bears are generally diurnal, meaning that they are active for the most part during the day. The belief that they are nocturnal apparently comes from the habits of bears that live near humans, which engage in some nocturnal activities, such as raiding trash cans or crops while avoiding humans. The sloth bear of Asia is the most nocturnal of the bears, but this varies by individual, and females with cubs are often diurnal to avoid competition with males and nocturnal predators.[26] Bears are overwhelmingly solitary and are considered to be the most asocial of all the Carnivora. Liaisons between breeding bears are brief, and the only times bears are encountered in small groups are mothers with young or occasional seasonal bounties of rich food (such as salmon runs).[26]

Vocalizations

Bears produce a variety of vocalizations such as:

- Moaning, produced mostly as mild warnings to potential threats or in fear,

- Barking, produced during times of alarm, excitement or to give away the animal's position.

- Huffing, made during courtship or between mother and cubs to warn of danger.

- Growling, produced as strong warnings to potential threats or in anger.

- Roaring, used much for the same reasons as growls and also to proclaim territory and for intimidation.

- Humming, a loud monotonous buzzing sound, primarily employed by cubs.[30]

Diet and interspecific interactions

.jpg)

Most bears have diets of more plant than animal matter and are completely opportunistic omnivores. In autumn, some bear species forage large amounts of fermented fruits, which affects their behavior.[31]Some bears will climb trees to obtain mast (edible vegetative or reproductive parts, such as acorns); smaller species that are more able to climb include a greater amount of this in their diets.[32] Such masts can be very important to the diets of these species, and mast failures may result in long-range movements by bears looking for alternative food sources.[33] There are two significant exceptions to this however:

- The polar bear, which has adopted a diet mainly of marine mammals to survive in the Arctic.

- The giant panda, which has adopted a diet mainly of bamboo.

Stable isotope analysis of the extinct giant short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) shows it was also an exclusive meat-eater, probably a scavenger.[34] The sloth bear, though not as specialized as the previous two species, has lost several front teeth usually seen in bears, and developed a long, suctioning tongue to feed on the ants, termites, and other burrowing insects they favour. At certain times of the year, these insects can make up 90% of their diets.[35] All bears will feed on any food source that becomes available, the nature of which varies seasonally. A study of Asiatic black bears in Taiwan found they would consume large numbers of acorns when they were most common, and switch to ungulates at other times of the year.[36]

Regarding warm-blooded animals, bears will typically take small or young animals, as they are easier to catch. However, both species of black bears and the brown bear can sometimes take large prey, such as ungulates.[36][37] Often, bears will feed on other large animals when they encounter a carcass, whether or not the carcass is claimed by, or is the kill of, another predator. This competition is the main source of interspecies conflict. Bears are able to defend a carcass against some comers. Mother bears also can usually defend their cubs against other predators.

The tiger is the only predator known to regularly prey on adult bears, including fully grown adults of brown bears, sloth bears, Asiatic black bears, and sun bears.[38][39][40][41][42][43] When hunting bears, tigers will position themselves from the leeward side of a rock or fallen tree, waiting for the bear to pass by. When the bear passes, the tiger will spring from an overhead position and grab the bear from under the chin with one forepaw and the throat with the other. The immobilised bear is then killed with a bite to the spinal column. After killing a bear, the tiger will concentrate its feeding on the bear's fat deposits, such as the back, legs and groin.[44][45]

Breeding

The age at which bears reach sexual maturity is highly variable, both between and within species. Sexual maturity is dependent on body condition, which is in turn dependent upon the food supply available to the growing individual. The females of smaller species may have young in as little as two years, whereas the larger species may not rear young until they are four or even nine years old. First breeding may be even later in males, where competition for mates may leave younger males without access to females.[26]

The bear's courtship period is very brief. Bears in northern climates reproduce seasonally, usually after a period of inactivity similar to hibernation, although tropical species breed all year round. Cubs are born toothless, blind, and bald. The cubs of brown bears, usually born in litters of one to three, will typically stay with the mother for two full seasons. They feed on their mother's milk through the duration of their relationship with their mother, although as the cubs continue to grow, nursing becomes less frequent and cubs learn to begin hunting with the mother. They will remain with the mother for about three years, until she enters the next cycle of estrus and drives the cubs off. Bears will reach sexual maturity in five to seven years. Male bears, especially polar and brown bears, will kill and sometimes devour cubs born to another father to induce a female to breed again. Female bears are often successful in driving off males in protection of their cubs, despite being rather smaller.

Hibernation

Many bears of northern regions hibernate in the winter.[46][47] During hibernation, the bear's metabolism slows down, its body temperature decreases slightly, and its heart rate slows from a normal value of 55 to just 9 beats per minute.[48] Bears normally do not wake during their hibernation, and can go the entire period without eating, drinking, urinating, or defecating. Female bears give birth during the hibernation period, and are roused when doing so.[47]

Relationship with humans

Some species, such as the polar bear, American black bear, grizzly bear, sloth bear, and brown bear, are dangerous to humans, especially in areas where they have become used to people. All bears are physically powerful and are likely capable of fatally attacking a person, but they, for the most part, are shy, are easily frightened and will avoid humans. Injuries caused by bears are rare, but are often widely reported.[49] The danger that bears pose is often vastly exaggerated, in part by the human imagination. However, when a mother feels that her cubs are threatened, she will behave ferociously. It is recommended to give all bears a wide berth; because, they are behaviorally unpredictable.

Where bears raid crops or attack livestock, they may come into conflict with humans.[50][51] These problems may be the work of only a few bears, but they create a climate of conflict, as farmers and ranchers may perceive all losses as due to bears and advocate the preventive removal of all bears.[51] Mitigation methods may be used to reduce bear damage to crops, and reduce local antipathy towards bears.[50]

Laws have been passed in many areas of the world to protect bears from habitat destruction. Public perception of bears is often very positive, as people identify with bears due to their omnivorous diets, ability to stand on two legs, and symbolic importance,[52] and support for bear protection is widespread, at least in more affluent societies.[53] In more rural and poorer regions, attitudes may be more shaped by the dangers posed by bears and the economic costs they cause to farmers and ranchers.[51] Some populated areas with bear populations have also outlawed the feeding of bears, including allowing them access to garbage or other food waste. Bears in captivity have been trained to dance, box, or ride bicycles; however, this use of the animals became controversial in the late 20th century. Bears were kept for baiting in Europe at least since the 16th century.

Bear hunt

Some cultures use bears for food and folk medicine. Their meat is dark and stringy, like a tough cut of beef. In Cantonese cuisine, bear paws are considered a delicacy. The peoples of China, Japan, and Korea use bears' body parts and secretions (notably their gallbladders and bile) as part of traditional Chinese medicine. More than 12,000 bile bears are thought to be kept on farms, for their bile, in China, Vietnam, and South Korea.[54] Bear meat must be cooked thoroughly, as it can be infected with Trichinella spiralis, which can cause trichinosis.[55][56][57]

Culture

Names

The female first name "Ursula", originally derived from a Christian saint's name and common in English- and German-speaking countries, means "little she-bear" (diminutive of Latin ursa). In Switzerland, the male first name "Urs" is especially popular, while the name of the canton and city of Bern is derived from Bär, German for bear. The Germanic name Bernard (including Bernhardt and other forms) means "bear-brave", "bear-hardy", or "bold bear".[58][59]

The Italian surname Orsini, the name of a prominent Medieval Aristocratic family, is ultimately derived from Latin ursinus ("bearlike") and originating as an epithet or sobriquet describing the name-bearer's purported strength.

In Scandinavia, the male personal names Björn (Sweden, Iceland) and Bjørn (Norway, Denmark), meaning "bear", are relatively common. In Finland, the male personal name Otso is an old poetic name for bear, similar to Kontio.

In Russian and other Slavic languages, the word for bear, medved (медведь), and variants or derivatives, such as Medvedev, are common surnames.

The Irish family name "McMahon" means "Son of Bear" in Irish.

In East European Jewish communities, the name Ber (בער)—Yiddish cognate of "Bear"—has been attested as a common male first name, at least since the 18th century, and was, among others, the name of several prominent rabbis. The Yiddish Ber is still in use among Orthodox Jewish communities in Israel, the US, and other countries. With the transition from Yiddish to Hebrew under the influence of Zionism, the Hebrew word for "bear", dov (דב), was taken up in contemporary Israel and is at present among the commonly used male first names in that country.

"Ten Bears" (Paruasemana) was the name of a well-known 19th-century chieftain among the Comanche. Also among other Native American tribes, bear-related names are attested.

Myth and legend

There is evidence of prehistoric bear worship. Anthropologists such as Joseph Campbell have regarded this as a common feature in most of the fishing and hunting-tribes. The prehistoric Finns, along with most Siberian peoples, considered the bear as the spirit of one's forefathers. This is why the bear (karhu) was a greatly respected animal, with several euphemistic names (such as otso, mesikämmen, and kontio). The bear is the national animal of Finland. This kind of attitude is reflected in the traditional Russian fairy tale "Morozko", whose arrogant protagonist Ivan tries to kill a mother bear and her cubs—and is punished and humbled by having his own head turned magically into a bear's head and being subsequently shunned by human society.

Pliny the Elder's Natural History (1st century AD) claims that "when first born, they are shapeless masses of white flesh, a little larger than mice; their claws alone being prominent. The mother then licks them gradually into proper shape."[60] This belief was echoed by authors of bestiaries throughout the medieval period.[61]

Evidence of bear worship has been found in early Chinese and Ainu cultures, as well (see Iomante). Korean people in their mythology identify the bear as their ancestor and symbolic animal. According to the Korean legend, a god imposed a difficult test on a she-bear; when she passed it, the god turned her into a woman and married her.

Legends of saints taming bears are common in the Alpine zone. In the arms of the bishopric of Freising, the bear is the dangerous totem animal tamed by St. Corbinian and made to carry his civilised baggage over the mountains. A bear also features prominently in the legend of St. Romedius, who is also said to have tamed one of these animals and had the same bear carry him from his hermitage in the mountains to the city of Trento. Similar stories are told of Saint Gall and Saint Columbanus.

This recurrent motif was used by the Church as a symbol of the victory of Christianity over paganism.[62] In the Norse settlements of northern England during the 10th century, a type of "hogback" grave cover of a long narrow block of stone, with a shaped apex like the roof beam of a long house, is carved with a muzzled, thus Christianised, bear clasping each gable end. Though the best collection of these is in the church at Brompton, North Yorkshire,[63] their distribution ranges across northern England and southern Scotland, with a scattered few in the north Midlands and single survivals in Wales, Cornwall, and Ireland; a late group is found in the Orkney Islands.

Bears are a popular feature of many children's stories, including Goldilocks and "The Story of the Three Bears", the Berenstain Bears, and Winnie the Pooh. "The Brown Bear of Norway" is a Scottish fairy tale telling the adventures of a girl who married a prince magically turned into a bear, and who managed to get him back into a human form by the force of her love and after many trials and difficulties. This story was adapted into the East German fantasy film The Singing Ringing Tree.

-

"En uheldig bjørnejakt" (An Unfortunate Bear Hunt) by Theodor Kittelsen, 1908

-

Onikuma from Ehon Hyaku Monogatari

-

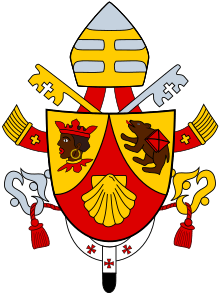

According to his hagiography, a bear killed Saint Corbinian's pack horse on the way to Rome, so the saint commanded it to carry his load. Once he arrived in Rome, however, he let the bear go.

-

The saddled "bear of St. Corbinian" the emblem of Freising, here incorporated in the arms of Pope Benedict XVI

-

Coat of Arms of the Abbey of Saint Gall

-

"The Three Bears", Arthur Rackham's illustration to English Fairy Tales, by Flora Annie Steel

Symbolic use

.jpg)

The Russian bear is a common national personification for Russia, as for the former Soviet Union. The brown bear is Finland's national animal.

In the United States, the black bear is the state animal of Louisiana, New Mexico, and West Virginia; the grizzly bear is the state animal of both Montana and California. Bears appear in the state seals of California and Missouri.

In the UK, the bear and staff has long featured on the heraldic arms of Warwickshire county.[64] Bears appear in the canting arms of two cities, Bern and Berlin, both of whose names include "bear". Bear symbols are used extensively in Berlin street decorations.[65]

Also, "bear", "bruin", or specific types of bears are popular nicknames or mascots for sports teams, including Bayern Munich, Chicago Bears, California Golden Bears, UCLA Bruins, Boston Bruins. A bear cub called Misha was mascot of the 1980 Summer Olympics in Moscow, Soviet Union.

Smokey Bear has become a part of American culture since his introduction in 1944. Known to almost all Americans, he and his message, "Only you can prevent forest fires" (updated in 2001 to "Only you can prevent wildfires"), have been a symbol of preserving woodlands.[66] Smokey wears a hat similar to one worn by U.S. Forest Service rangers; state police officers in some states wear a similar style, giving rise to the CB slang "bear" or "Smokey" for the highway patrol.

The name Beowulf or "bee-wolf" is a kenning for bear, meaning a brave warrior.[67]

Figures of speech

The physical attributes and behaviours of bears are commonly used in figures of speech in English.

- In the stock market, a bear market is a period of declining prices. Pessimistic forecasting or negative activity is said to be bearish (due to the stereotypical posture of bears looking downwards), and one who expresses bearish sentiment is a bear. Its opposite is a bull market, and bullish sentiment from bulls.

- In gay slang, the term "bear" refers to male individuals who possess physical attributes much like a bear, such as a heavy build, abundant body hair, and commonly facial hair.

- A bear hug is typically a tight hug that involves wrapping one's arms around another person, often leaving that person's arms immobile.

- Bear tracking – in the old Western states of the U.S. and, to this day, in the former Dakota Territory, the expression "you ain't just a bear trackin'" is used to mean "you ain't lying" or "that's for sure". This expression evolved as an outgrowth of the experience pioneer hunters and mountainmen had when tracking bear. Bears often lay down false tracks and are notorious for doubling back on anything tracking them. If you are not following bear tracks, you are not following false trails or leads in your thoughts, words or deeds.

- In Korean culture, a person is referred to as being "like a bear" when they are stubborn or not sensitive to what is happening around their surroundings. Used as a phrase to call a person "stubborn bear".

- The Bible compares King David's "bitter warriors", who fight with such fury that they could overcome many times their number of opponents, with "a bear robbed of her whelps in the field" (2 Samuel 17:8 s:Bible (King James)/2 Samuel#Chapter 17). The phrase "a bereaved bear" (דב שכול), derived from this Biblical source, is still used in the literary Hebrew of contemporary Israel.

Teddy bears

Around the world, many children have stuffed toys in the form of bears.

Organizations regarding bears

Two authoritative organizations for seeking scientific information on bear species of the world are the International Association for Bear Research & Management, also known as the International Bear Association (IBA); and the Bear Specialist Group of the Species Survival Commission, a part of the International Union for the Conservation of Nature. These organizations focus on the species' natural history, management, and conservation.

Other organizations exist to further wild bear education and conservation. Bear Trust International works for wild bears and other wildlife through four core program initiatives:

- Conservation Education,

- Wild Bear Research,

- Wild Bear Management, and,

- Habitat Conservation.[68]

Specialty organizations for each of the eight species of bears worldwide include:

- Brown bear: "Vital Ground".

- Asiatic black bear: "Moon Bears".

- North American black bear: "Black Bear Conservation Coalition".

- Polar bear: "Polar Bears International".

- Sun bear: "Bornean Sun Bear Conservation Centre".

- Sloth bear: "Wildlife SOS".

- Andean bear: "Andean Bear Conservation Project".

- Giant panda: "Chengdu Research Base of Giant Panda Breeding".

See also

- List of fatal bear attacks in North America

- List of fictional bears

- List of individual bears

- Ursa Minor

- Ursari

References

- ↑ Peter Tyson. "Bear Essentials of Hibernation". Pbs.org. Retrieved 2013-09-26.

- 1 2 Pokorny (1959) indo-european.nl Archived September 1, 2011, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ hildebrand.raa.se

- ↑ Votruba, Martin. "Bears". Slovak Studies Program. University of Pittsburgh. Archived from the original on 20 January 2012. Retrieved 2009-03-12.

- ↑ Welsey-Hunt, G.D. & Flynn, J.J. (2005). "Phylogeny of the Carnivora: basal relationships among the Carnivoramorphans, and assessment of the position of 'Miacoidea' relative to Carnivora". Journal of Systematic Palaeontology. 3 (1): 1–28. doi:10.1017/S1477201904001518.

- ↑ Wang, Xiaoming; Malcolm C. McKenna & Demberelyin Dashzeveg (2005). "Amphicticeps and Amphicynodon (Arctoidea, Carnivora) from Hsanda Gol Formation, Central Mongolia and Phylogeny of Basal Arctoids with Comments on Zoogeography" (PDF). American Museum Novitates (3483): 57. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-02-07.

- ↑ Kemp, T.S. (2005). The Origin and Evolution of Mammals. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-850760-4.

- ↑ Wang Banyue & Qiu Zhanxiang (2005). "Notes on Early Oligocene Ursids (Carnivora, Mammalia) from Saint Jacques, Nei Mongol, China" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 279 (279): 116–124. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2003)279<0116:C>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-11-20.

- ↑ Waits, Lisette (1999). "Rapid radiation events in the family Ursidae indicated by likelihood phylogenetic estimation from multiple fragments of mtDNA" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 13: 82–92. doi:10.1006/mpev.1999.0637. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Pàges, Marie (2008). "Combined analysis of fourteen nuclear genes refines the Ursidae phylogeny" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 47: 73–83. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2007.10.019. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 Krause, J.; Unger, T.; Noçon, A.; Malaspinas, A.; Kolokotronis, S.; Stiller, M.; Soibelzon, L.; Spriggs, H.; Dear, P. H.; Briggs, A. W.; Bray, S. C. E.; O'Brien, S. J.; Rabeder, G.; Matheus, P.; Cooper, A.; Slatkin, M.; Pääbo, S.; Hofreiter, M. (2008-07-28). "Mitochondrial genomes reveal an explosive radiation of extinct and extant bears near the Miocene-Pliocene boundary". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 8 (220): 220. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-8-220. PMC 2518930

. PMID 18662376.

. PMID 18662376. - ↑ Soibelzon, L. H.; Tonni, E. P.; Bond, M. (October 2005). "The fossil record of South American short-faced bears (Ursidae, Tremarctinae)". Journal of South American Earth Sciences. 20 (1–2): 105–113. doi:10.1016/j.jsames.2005.07.005.

- ↑ Qiu Zhanxiang (2003). "Dispersals of Neogene Carnivorans between Asia and North America" (PDF). Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 279 (279): 18–31. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2003)279<0018:C>2.0.CO;2. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2009-11-20.

- ↑ Kurtén, B., 1995. The cave bear story: life and death of a vanished animal, Columbia University Press, ISBN 0-231-10361-1

- ↑ Lindburg, Donald G. (2004). Giant Pandas: Biology and Conservation, pp. 7–9. University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23867-2

- ↑ Olaf R. P. Bininda-Emonds. "Phylogenetic Position of the Giant Panda". In Lindburg, Donald G. (2004) Giant Pandas: Biology and Conservation, pp. 11–35. University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-23867-2

- ↑ Kutschera, Verena (2014). "Bears in a forest of gene trees: Phylogenetic inference is complicated by incomplete lineage sorting and gene flow". Molecular Biology and Evolution. 31: 2004–2017. doi:10.1093/molbev/msu186. Retrieved 17 November 2014.

- ↑ Flynn, J. J.; Nedbal, M. A.; Dragoo, J. W.; Honeycutt, R. L. (2000). "Whence the Red Panda?" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 17 (2): 190–199. doi:10.1006/mpev.2000.0819. PMID 11083933. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- ↑ Flynn JJ, Finarelli JA, Zehr S, Hsu J, Nedbal MA (2005). "Molecular phylogeny of the carnivora (mammalia): assessing the impact of increased sampling on resolving enigmatic relationships". Systematic Biology. 54 (2): 317–337. doi:10.1080/10635150590923326. PMID 16012099.

- ↑ Flynn, J. J.; Nedbal, M. A. (1998). "Phylogeny of the Carnivora (Mammalia): Congruence vs Incompatibility among Multiple Data Sets". Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 9 (3): 414–426. doi:10.1006/mpev.1998.0504. PMID 9667990. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18.. Retrieved 2009-10-08.

- ↑ "The Brown Bear: Father of the Polar Bear?, Alaska Science Forum". Gi.alaska.edu. 1996-12-05. Archived from the original on 2010-01-17. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ↑ Cahill, James A.; Green, Richard E.; Fulton, Tara L.; Stiller, Mathias; Jay, Flora; Ovsyanikov, Nikita; Salamzade, Rauf; John, John St; Stirling, Ian; Slatkin, Montgomery; Shapiro, Beth (14 March 2013). "Genomic Evidence for Island Population Conversion Resolves Conflicting Theories of Polar Bear Evolution". PLOS Genet. 9 (3): e1003345. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1003345. PMC 3597504

. PMID 23516372 – via PLoS Journals.

. PMID 23516372 – via PLoS Journals. - ↑ Derocher, Andrew E.; Andersen, Magnus; Wiig, Øystein (2005). "Sexual dimorphism of polar bears" (PDF). Journal of Mammalogy. 86 (5): 895–901. doi:10.1644/1545-1542(2005)86[895:SDOPB]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 Hunt, R. M. Jr. (1998). "Ursidae". In Janis, Christine M.; Scott, Kathleen M.; Jacobs, Louis L. Evolution of Tertiary Mammals of North America, volume 1: Terrestrial carnivores, ungulates, and ungulatelike mammals. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press. pp. 174–195. ISBN 978-0-521-35519-3.

- 1 2 Wood, Gerald (1983). The Guinness Book of Animal Facts and Feats. ISBN 978-0-85112-235-9.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Garshelis, David L. (2009). "Family Ursidae (Bears)". In Wilson, Don; Mittermeier, Russell. Handbook of the Mammals of the World. Volume 1: Carnivores. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. ISBN 978-84-96553-49-1.

- 1 2 Carnivores of the World by Dr. Luke Hunter. Princeton University Press (2011), ISBN 978-0-691-15228-8

- 1 2 Novak, R. M. 1999. Walker's Mammals of the World. 6th edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9

- ↑ Bunnell, Fred (1984). Macdonald, D., ed. The Encyclopedia of Mammals. New York: Facts on File. p. 87. ISBN 978-0-87196-871-5.

- ↑ Peters, G.; Owen, M. & Rogers, L. (2007). "Humming in bears: a peculiar sustained mammalian vocalization" (PDF). Acta Theriologica. 52 (4): 379–389. doi:10.1007/BF03194236.

- ↑ "Slovakia warns of tipsy bears". Archived from the original on 2010-11-18. Retrieved 2008-11-11.

- ↑ Mattson, David J. (1998). "Diet and Morphology of Extant and Recently Extinct Northern Bears". Ursus, A Selection of Papers from the Tenth International Conference on Bear Research and Management, Fairbanks, Alaska, July 1995, and Mora, Sweden, September 1995. 10: 479–496. JSTOR 3873160.

- ↑ Ryan, Christopher; Pack, James C.; Igo, William K.; Billings, Anthony (2007). "Influence of mast production on black bear non-hunting mortalities in West Virginia". Ursus. 18 (1): 46–53. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2007)18[46:IOMPOB]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Matheus, Paul E. (1995). "Diet and Co-ecology of Pleistocene Short-Faced Bears and Brown Bears in Eastern Beringia". Quaternary Research. 44 (3): 447–453. doi:10.1006/qres.1995.1090.

- ↑ Joshi, Anup; Garshelis, David L.; Smith, James L. D. (1997). "Seasonal and Habitat-Related Diets of Sloth Bears in Nepal". Journal of Mammalology. 1978 (2): 584–597. doi:10.2307/1382910.

- 1 2 Hwang, Mei-Hsiu (2002). "Diets of Asiatic black bears in Taiwan, with Methodological and Geographical Comparisons" (PDF). Ursus. 13: 111–125.

- ↑ Zager, Peter; Beecham, John (2006). "The role of American black bears and brown bears as predators on ungulates in North America". Ursus. 17 (2): 95–108. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2006)17[95:TROABB]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Seryodkin, Ivan (2006). "The ecology, behavior, management and conservation status of brown bears in Sikhote-Alin (in Russian).". Far Eastern National University, Vladivostok, Russia. pp. 1–252.

- ↑ Geptner, V. G., Sludskii, A. A. (1972). Mlekopitaiuščie Sovetskogo Soiuza. Vysšaia Škola, Moskva. (In Russian; English translation: Heptner, V. G.; Sludskii, A. A.; Bannikov, A. G.; (1992). the Soviet Union. Volume II, Part 2: Carnivora (Hyaenas and Cats). Smithsonian Institution and the National Science Foundation, Washington DC). Pp. 95–202.

- ↑ Frasef, A. (2012). Feline Behaviour and Welfare. CABI. pp. 72–77. ISBN 978-1-84593-926-7.

- ↑ David Prynn (2004). Amur tiger. Russian Nature Press. p. 115.

- ↑ Seryodkin; et al. (2003). "Denning ecology of brown bears and Asiatic black bears in the Russian Far East". Ursus. 14 (2): 159.

- ↑ Kawanishi, K. and M. E. Sunquist (2004). Conservation status of tigers in a primary rainforest of Peninsular Malaysia. Biological Conservation 120: 329–344.

- ↑ V.G Heptner & A.A. Sludskii. Mammals of the Soviet Union, Volume II, Part 2. pp. 175–177. ISBN 90-04-08876-8.

- ↑ Anatoliy Grigorievitch Yudakov & Igor Georgievitch Nikolaev (2004). "Hunting Behavior and Success of the Tigers' Hunts". The Ecology of the Amur Tiger based on Long-Term Winter Observations in 1970–1973 in the Western Sector of the Central Sikhote-Alin Mountains (english translation ed.). Institute of Biology and Soil Science, Far-Eastern Scientific Center, Academy of Sciences of the USSR.

- ↑ Gerhard Heldmeier (2011). "Life on Low Flame in Hibernation". Science. 331 (6019): 866–867. doi:10.1126/science.1203192.

- 1 2 Shimozuru, M.; et al. (2013). "Pregnancy during hibernation in Japanese black bears: effects on body temperature and blood biochemical profiles". Journal of Mammalogy. 94 (3): 618–627. doi:10.1644/12-MAMM-A-246.1.

- ↑ Tøien, Ø.; et al. (2011). "Hibernation in Black Bears: Independence of Metabolic Suppression from Body Temperature". Science. 331 (6019): 906–909. doi:10.1126/science.1199435. PMID 21330544.

- ↑ Clark, Douglas (2003). "Polar Bear–Human Interactions in Canadian National Parks, 1986–2000" (PDF). Ursus. 14 (1): 65–71.

- 1 2 Fredriksson, Gabriella (2005). "Human–sun bear conflicts in East Kalimantan, Indonesian Borneo". Ursus. 16 (1): 130–137. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2005)016[0130:HBCIEK]2.0.CO;2.

- 1 2 3 Goldstein, Isaac; Paisley, Susanna; Wallace, Robert; Jorgenson, Jeffrey P.; Cuesta, Francisco; Castellanos, Armando (2006). "Andean bear–livestock conflicts: a review". Ursus. 17 (1): 8–15. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2006)17[8:ABCAR]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Kellert, Stephen (1994). "Public Attitudes toward Bears and Their Conservation". Bears: Their Biology and Management. 9 (1): 43–50. doi:10.2307/3872683. JSTOR 3872683.

- ↑ Andersone, Žanete; Ozolinš, Jānis (2004). "Public perception of large carnivores in Latvia". Ursus. 15 (2): 181–187. doi:10.2192/1537-6176(2004)015<0181:PPOLCI>2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Black, Richard (2007-06-11). "BBC Test kit targets cruel bear trade". BBC News. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18. Retrieved 2010-01-01.

- ↑ "Trichinellosis Associated with Bear Meat". Archived from the original on 30 September 2006. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ "Bear meat poisoning in Siberia". BBC News. 1997-12-21. Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ "Finnish Food Safety Authority: Bear meat must be inspected before serving in restaurants". Retrieved 2006-10-04.

- ↑ "Ursa Major – the Greater Bear". constellationsofwords.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ↑ "Bernhard Family History". ancestry.com. Retrieved March 11, 2015.

- ↑ Pliny. Natural History 8.4 Trans. Bostock and Riley (1855)

- ↑ Badke, David. The Medieval Bestiary: Bear

- ↑ Pastoreau, Michel (2007) L'ours. Historie d'un roi déchu, Seuil ISBN 2-02-021542-X.

- ↑ Noted and illustrated in Hall, Richard (1995) Viking Age Archaeology, p. 43 and fig. 22, ISBN 0-7478-0063-4.

- ↑ "CIVIC HERALDRY OF ENGLAND AND WALES-WARWICKSHIRE".

- ↑ "The first Buddy Bears in Berlin". Buddy Bear Berlin. Buddy Bär Berlin GmbH. 2008. Retrieved 30 January 2014.

- ↑ "Forest Fire Prevention – Smokey Bear (1944–Present)". Ad Council. 1944-08-09. Archived from the original on 2010-11-18. Retrieved 2010-10-16.

- ↑ Sweet, Henry (1884) Anglo-Saxon Reader in Prose and Verse. The Clarendon Press, p. 202.

- ↑ "Vision and Mission". Bear Trust International. 2002–2012. Retrieved March 8, 2014.

Further reading

- Bears of the World, Terry Domico, photographs by Terry Domico and Mark Newman, Facts on File, Inc., 1988, hardcover, ISBN 978-0-8160-1536-8.

- The Bear by William Faulkner.

- Brunner, Bernd: Bears: A Brief History. New Haven and London: Yale University Press, 2007.

External links

- The Bears Project – Information, reports and images of European brown bears and other living species

- Western Wildlife Outreach – Information on the history, biology, and conservation of North American Grizzly Bears and Black Bears

- The Bear Book and Curriculum Guide – a compilation of stories about all eight species of bears worldwide, including STEM lessons rooted in bear research, ecology, and conservation