Lion

| Lion[1] Temporal range: early Pleistocene–Recent | |

|---|---|

| |

| Male | |

| |

| Female (lioness) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Clade: | Synapsida |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Family: | Felidae |

| Subfamily: | Pantherinae |

| Genus: | Panthera |

| Species: | P. leo |

| Binomial name | |

| Panthera leo (Linnaeus, 1758)[3] | |

| Subspecies | |

|

Panthera leo subspecies

P. l. azandica | |

| |

| |

| Distribution of lions in India: The Gir Forest, in Gujarat, is the last natural range of more than 500 wild Asiatic lions. There are plans to reintroduce some lions to Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary in neighbouring Madhya Pradesh. | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Linnaeus, 1758[3] | |

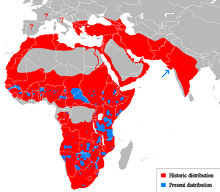

The lion (Panthera leo) is one of the big cats in the genus Panthera and a member of the family Felidae. The commonly used term African lion collectively denotes the several subspecies in Africa. With some males exceeding 250 kg (550 lb) in weight,[4] it is the second-largest living cat after the tiger. Wild lions currently exist in sub-Saharan Africa and in India (where an endangered remnant population resides in Gir Forest National Park). In ancient historic times, their range was in most of Africa, including North Africa, and across Eurasia from Greece and southeastern Europe to India. In the late Pleistocene, about 10,000 years ago, the lion was the most widespread large land mammal after humans: Panthera leo spelaea lived in northern and western Europe and Panthera leo atrox lived in the Americas from the Yukon to Peru.[5] The lion is classified as a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), having seen a major population decline in its African range of 30–50% per two decades during the second half of the twentieth century.[2] Lion populations are untenable outside designated reserves and national parks. Although the cause of the decline is not fully understood, habitat loss and conflicts with humans are the greatest causes of concern. Within Africa, the West African lion population is particularly endangered.

In the wild, males seldom live longer than 10 to 14 years, as injuries sustained from continual fighting with rival males greatly reduce their longevity.[6] In captivity they can live more than 20 years. They typically inhabit savanna and grassland, although they may take to bush and forest. Lions are unusually social compared to other cats. A pride of lions consists of related females and offspring and a small number of adult males. Groups of female lions typically hunt together, preying mostly on large ungulates. Lions are apex and keystone predators, although they are also expert scavengers obtaining over 50 percent of their food by scavenging as opportunity allows. While lions do not typically hunt humans, some have. Sleeping mainly during the day, lions are active primarily at night (nocturnal), although sometimes at twilight (crepuscular).[7][8]

Highly distinctive, the male lion is easily recognised by its mane, and its face is one of the most widely recognised animal symbols in human culture. Depictions have existed from the Upper Paleolithic period, with carvings and paintings from the Lascaux and Chauvet Caves in France dated to 17,000 years ago, through virtually all ancient and medieval cultures where they once occurred. It has been extensively depicted in sculptures, in paintings, on national flags, and in contemporary films and literature. Lions have been kept in menageries since the time of the Roman Empire, and have been a key species sought for exhibition in zoos over the world since the late eighteenth century. Zoos are cooperating worldwide in breeding programs for the endangered Asiatic subspecies.

Etymology

The lion's name, similar in many Romance languages, is derived from the Latin leo,[9] and the Ancient Greek λέων (leon).[10] The Hebrew word לָבִיא (lavi) may also be related.[11] It was one of the species originally described by Linnaeus, who gave it the name Felis leo, in his eighteenth-century work, Systema Naturae.[3]

Taxonomy and evolution

.png)

The lion's closest relatives are the other species of the genus Panthera: the tiger, the snow leopard, the jaguar, and the leopard. Studies from 2006 and 2009 concluded that the jaguar is a sister species to the lion and the leopard is a sister taxon to the jaguar/lion clade[12][13] while 2010 and 2011 studies have swapped the positions leopard and jaguar.[14][15] P. leo evolved in Africa between 1 million and 800,000 years ago, before spreading throughout the Holarctic region.[16] It appeared in the fossil record in Europe for the first time 700,000 years ago with the subspecies Panthera leo fossilis at Isernia in Italy. From this lion derived the later cave lion (Panthera leo spelaea),[17] which appeared about 300,000 years ago. Lions died out in northern Eurasia at the end of the last glaciation, about 10,000 years ago; this may have been secondary to the extinction of Pleistocene megafauna.[18][19]

Subspecies

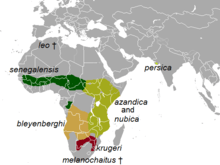

Traditionally, 12 recent subspecies of lion were recognised, distinguished by mane appearance, size, and distribution. Because these characteristics are very insignificant and show a high individual variability, most of these forms were probably not true subspecies, especially as they were often based upon zoo material of unknown origin that may have had "striking, but abnormal" morphological characteristics.[20] Today, only eight subspecies are usually accepted,[19][21] although one of these, the Cape lion, formerly described as Panthera leo melanochaita, is probably invalid.[21] Even the remaining seven subspecies might be too many. While the status of the Asiatic lion (P. l. persica) as a subspecies is generally accepted, the systematic relationships among African lions are still not completely resolved. Mitochondrial variation in living African lions seemed to be modest according to some newer studies; therefore, all sub-Saharan lions have sometimes been considered a single subspecies. However, a recent study revealed lions from western and central Africa differ genetically from lions of southern or eastern Africa. According to this study, Western African lions are more closely related to Asian lions than to South or East African lions. These findings might be explained by a late Pleistocene extinction event of lions in western and central Africa, and a subsequent recolonisation of these parts from Asia.[22]

Previous studies, which were focused mainly on lions from eastern and southern parts of Africa, already showed these can be possibly divided in two main clades: one to the west of the Great Rift Valley and the other to the east. Lions from Tsavo in eastern Kenya are much closer genetically to lions in Transvaal (South Africa), than to those in the Aberdare Range in western Kenya.[23] Another study revealed there are three major types of lions, one North African–Asian, one southern African and one middle African.[24] Conversely, Per Christiansen found that using skull morphology allowed him to identify the subspecies krugeri, nubica, persica, and senegalensis, while there was overlap between bleyenberghi with senegalensis and krugeri. The Asiatic lion persica was the most distinctive, and the Cape lion had characteristics allying it more with P. l. persica than the other sub-Saharan lions. He had analysed 58 lion skulls in three European museums.[25] Based on recent genetic studies, the Cat Classification Task Force of the IUCN SSC Cat Specialist Group has provisionally proposed to assign the lions occurring in Asia and West, Central and North Africa to the subspecies Panthera leo leo and the lions inhabiting South and East Africa to the subspecies Panthera leo melanochaita.[26] The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has followed this revised taxonomic classification, as being based on "the best available scientific and commercial information", in listing these two subspecies as, respectively, endangered and threatened.[27]

The majority of lions kept in zoos are hybrids of different subspecies. Approximately 77% of the captive lions registered by the International Species Information System are of unknown origin. Nonetheless, they might carry genes that are extinct in the wild, and might be therefore important to maintain overall genetic variability of the lion.[21] It is believed that those lions, imported to Europe before the middle of the nineteenth century, were mainly either Barbary lions from North Africa or lions from the Cape.[28]

Recent

Eight recent (Holocene) subspecies are recognised today:

| Subspecies | Description | Image |

|---|---|---|

| Barbary lion (P. l. leo), also called the Atlas lion or North African lion | Formerly found in Algeria, Morocco, Tunisia, and Egypt, this is the nominate lion subspecies from North Africa. It is extinct in the wild due to excessive hunting; the last wild Barbary lion was killed in Morocco in 1920.[29][30] This is one of the largest of the lion subspecies,[31] with reported lengths of 3.0–3.3 m (9.8–10.8 ft) and weights of more than 200 kg (440 lb) for males. It appears to be more closely related to the Asiatic rather than sub-Saharan lions. A number of animals in captivity are likely to be Barbary lions,[32] particularly the 90 animals descended from the Moroccan Royal collection at Rabat Zoo.[33] |  |

| Asiatic lion (P. l. persica), also known as Indian lion or Persian lion | Is found in Gir Forest National Park of northwestern India. Once was widespread from Turkey, across Southwest Asia, to India and Pakistan,[34] now 523 exist in and near the Gir Forest of Gujarat.[35] Genetic evidence suggests its ancestors split from the ancestors of sub-Saharan African lions between 203 and 74 thousand years ago.[19]

Southern Europe: (Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro and Serbia)

|

|

| West African lion (P. l. senegalensis), also known as Senegal lion | Found in western Africa, from Senegal to the Central African Republic.[36][37] It is currently listed as critically endangered in 2015. It is among the smallest of the Sub-Saharan African lions.

Western Africa: (Benin, Burkina Faso, Ghana,[38] Mali, Mauritania, Nigeria, and Senegal)

|

|

| Masai lion (P. l. nubica), also known as the East African lion | Found in East Africa, from Ethiopia and Kenya to Tanzania and Mozambique;[37] a local population is known as the Tsavo lion.

Eastern Africa: (Djibouti, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, Sudan, Tanzania, Uganda) |

|

| Congo lion (P. l. azandica), also known as Northeast Congo lion | Found in the northeastern parts of the Congo.[36] It is currently extinct in Rwanda.

Central Africa: (Central African Republic, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Rwanda, South Sudan, Sudan, Uganda) |

|

| Southwest African lion (P. l. bleyenberghi), also known as Katanga lion | Found in southwestern Africa and the Democratic Republic of the Congo. It is among the largest subspecies of African lions.

Southern Africa: (Angola, Botswana, Katanga (Democratic Republic of the Congo), Namibia, Zambia, Zimbabwe)[37] |

|

| Transvaal lion (P. l. krugeri), also known as Southeast African lion | Found in the Transvaal region of southeastern Africa, including Kruger National Park.[37]

Southern Africa: (Botswana, Mozambique, South Africa, Swaziland, Zimbabwe) |

|

| Ethiopian lion (P. l. roosevelti), also known as Addis Ababa lion | A newly discerned lion subspecies could exist in captivity in Ethiopia's capital city of Addis Ababa.[39] Researchers compared the microsatellite variations over ten loci of fifteen lions in captivity with those of six different wild lion populations. They determined that these lions are genetically unique and presumably that "their wild source population is similarly unique." These lions—with males that have a distinctly dark and luxuriant mane seem to define a new subspecies perhaps native only to Ethiopia. These lions were part of a collection of the late Haile Selassie I of Ethiopia.[40]

Northeastern Africa: (Ethiopia) |

Pleistocene

Several additional subspecies of lion existed in prehistoric times:

- P. l. fossilis, known as the Middle Pleistocene European cave lion, flourished about 500,000 years ago; fossils have been recovered from Germany and Italy. It was larger than today's African lions, reaching sizes comparable to the American cave lion and slightly larger than the Upper Pleistocene European cave lion.[19][41]

.jpg)

- P. l. spelaea, known as the European cave lion, Eurasian cave lion, or Upper Pleistocene European cave lion, occurred in Eurasia 300,000 to 10,000 years ago.[19] This species is known from Paleolithic cave paintings, ivory carvings, and clay busts,[42] indicating it had protruding ears, tufted tails, perhaps faint tiger-like stripes, and at least some had a ruff or primitive mane around their necks, possibly indicating males.[43]

- P. l. atrox, known as the American lion or American cave lion, was abundant in the Americas from Canada to Peru in the Pleistocene Epoch until about 10,000 years ago. This form is the sister clade of P. l. spelaea, and likely arose when an early P. l. spelaea population became isolated south of the North American continental ice sheet about 0.34 Mya.[44] One of the largest purported lion subspecies to have existed, its body length is estimated to have been 1.6–2.5 m (5.2–8.2 ft).[45]

Dubious

- P. l. youngi or Panthera youngi, flourished 350,000 years ago.[5] Its relationship to the extant lion subspecies is obscure, and it probably represents a distinct species.

- P. l. sinhaleyus, known as the Sri Lanka lion, appears to have become extinct around 39,000 years ago. It is only known from two teeth found in deposits at Kuruwita. Based on these teeth, P. Deraniyagala erected this subspecies in 1939.[46]

- P. l. vereshchagini, the Beringian cave lion of Yakutia (Russia), Alaska (United States), and the Yukon Territory (Canada), has been considered a subspecies separate from P. l. spelaea on morphological grounds. However, mitochondrial DNA sequences obtained from cave lion fossils from Europe and Alaska were indistinguishable.[44]

- P. l. mesopotamica or Mesopotamian lion, flourished during the Neo-Assyrian Period (approximately 1000–600 BC).[47] It inhabited the Mesopotamian Plain where it probably represents a distinct sub-species. Nearly all ancient Mesopotamian representations of male lions demonstrate full underbelly hair in which until recently was only identified in the Barbary lion (Panthera leo leo) from Northern Africa and in most Asiatic lions (P. l. persica) from captivity in colder climates. Ancient evidence from adjacent landmasses reveal no substantiation for lions with underbelly hair in this manner so that the distinct phenotype of depicted lions in ancient Mesopotamia (including Babylon, Elam and ancient Persia) represent an extinct sub-species. Many of the images of these lions are derived from lion hunting sculptures so that the extinction of this sub-species likely resulted from overhunting in the ancient world.

- P. l. europaea, known as the European lion, was probably identical with Panthera leo persica or Panthera leo spelea. It became extinct around 100 AD due to persecution and over-exploitation. It inhabited the Balkans, the Italian Peninsula, southern France, and the Iberian Peninsula. It was a very popular object of hunting among ancient Romans and Greeks.

- P. l. maculatus, known as the marozi or spotted lion, sometimes is believed to be a distinct subspecies, but may be an adult lion that has retained its juvenile spotted pattern. If it was a subspecies in its own right, rather than a small number of aberrantly coloured individuals, it has been extinct since 1931. A less likely identity is a natural leopard-lion hybrid commonly known as a leopon.[48]

Hybrids

Lions have been known to breed with tigers (most often the Siberian and Bengal subspecies) to create hybrids called ligers and tiglons (or tigons).[49] They also have been crossed with leopards to produce leopons,[50] and jaguars to produce jaglions. The marozi is reputedly a spotted lion or a naturally occurring leopon, while the Congolese spotted lion is a complex lion-jaguar-leopard hybrid called a lijagulep. Such hybrids were once commonly bred in zoos, but this is now discouraged due to the emphasis on conserving species and subspecies. Hybrids are still bred in private menageries and in zoos in China.

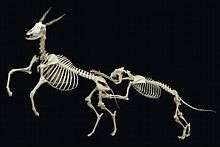

The liger is a cross between a male lion and a tigress.[51] Because the growth-inhibiting gene from the female tiger mother is absent, the growth-promoting gene passed on by the male lion father is unimpeded by a regulating gene and the resulting ligers grow far larger than either parent. They share physical and behavioural qualities of both parent species (spots and stripes on a sandy background). Male ligers are sterile, but female ligers often are fertile. Males have about a 50% chance of having a mane, but if they grow them, their manes will be modest: around 50% the size of a pure lion mane.

Ligers are much bigger than normal lions, typically 3.65 m (12.0 ft) in length, and can weigh up to 500 kg (1,100 lb).[52]

The less common tiglon or tigon is a cross between a lioness and a male tiger.[53] In contrast to ligers, tigons are often relatively small in comparison to their parents, because of reciprocal gene effects.[52]

Characteristics

Of the living felids the lion is second only to the tiger in length and weight. Its skull is very similar to that of the tiger, although the frontal region is usually more depressed and flattened, with a slightly shorter postorbital region and broader nasal openings than that of a tiger. However, due to the amount of skull variation in the two species, usually only the structure of the lower jaw can be used as a reliable indicator of species.[54] Lion colouration varies from light buff to yellowish, reddish, or dark ochraceous brown. The underparts are generally lighter and the tail tuft is black. Lion cubs are born with brown rosettes (spots) on their body, rather like those of a leopard. Although these fade as lions reach adulthood, faint spots often may still be seen on the legs and underparts, particularly on lionesses.

Lions are the only members of the cat family to display obvious sexual dimorphism – that is, males and females look distinctly different. They also have specialised roles that each gender plays in the pride. For instance, the lioness, the hunter, lacks the male's thick mane. The colour of the male's mane varies from blond to black, generally becoming darker as the lion grows older. The most distinctive characteristic shared by both females and males is that the tail ends in a hairy tuft. In some lions, the tuft conceals a hard "spine" or "spur", approximately 5 mm long, formed of the final sections of tail bone fused together. The lion is the only felid to have a tufted tail – the function of the tuft and spine are unknown. Absent at birth, the tuft develops around 5 1⁄2 months of age and is readily identifiable at 7 months.[55]

Nowak indicates the typical weight range of lions as 150 to 250 kg (331 to 551 lb) for males and 120 to 185 kg (265 to 408 lb) for females.[4] The size of adult lions varies across their range with those from the southern African populations in Zimbabwe, the Kalahari and Kruger Park averaging around 189.6 kg (418 lb) and 126.9 kg (280 lb) in males and females respectively compared to 174.9 kg (386 lb) and 119.5 kg (263 lb) of male and female lions from East Africa.[56] Reported body measurements in males are head-body lengths ranging from 170 to 250 cm (5 ft 7 in to 8 ft 2 in), tail lengths of 90–105 cm (2 ft 11 in–3 ft 5 in). In females reported head-body lengths range from 140 to 175 cm (4 ft 7 in to 5 ft 9 in), tail lengths of 70–100 cm (2 ft 4 in–3 ft 3 in),[4] however, the frequently cited maximum head and body length of 250 cm (8 ft 2 in) fits rather to extinct Pleistocene forms, like the American lion, with even large modern lions measuring several centimetres less in length.[57] Record measurements from hunting records are supposedly a total length of nearly 3.6 m (12 ft) for a male shot near Mucsso, southern Angola in October 1973 and a weight of 313 kg (690 lb) for a male shot outside Hectorspruit in eastern Transvaal, South Africa in 1936.[58] Another notably outsized male lion, which was shot near Mount Kenya, weighed in at 272 kg (600 lb).[29]

Mane

The mane of the adult male lion, unique among cats, is one of the most distinctive characteristics of the species. In rare cases a female lion can have a mane.[59][60] The presence, absence, colour, and size of the mane is associated with genetic precondition, sexual maturity, climate, and testosterone production; the rule of thumb is the darker and fuller the mane, the healthier the lion. Sexual selection of mates by lionesses favours males with the densest, darkest mane.[61] Research in Tanzania also suggests mane length signals fighting success in male–male relationships. Darker-maned individuals may have longer reproductive lives and higher offspring survival, although they suffer in the hottest months of the year.[62]

Scientists once believed that the distinct status of some subspecies could be justified by morphology, including the size of the mane. Morphology was used to identify subspecies such as the Barbary lion and Cape lion. Research has suggested, however, that environmental factors such as average ambient temperature influence the colour and size of a lion's mane.[62] The cooler ambient temperature in European and North American zoos, for example, may result in a heavier mane. Thus the mane is not an appropriate marker for identifying subspecies.[21][63] The males of the Asiatic subspecies, however, are characterised by sparser manes than average African lions.[64]

In the Pendjari National Park area almost all males are maneless or have very weak manes.[65] Maneless male lions have also been reported from Senegal, from Sudan (Dinder National Park), and from Tsavo East National Park in Kenya, and the original male white lion from Timbavati also was maneless. The testosterone hormone has been linked to mane growth; therefore, castrated lions often have minimal to no mane, as the removal of the gonads inhibits testosterone production.[66] In addition, increased testosterone may be the cause of the maned lionesses of northern Botswana.[67]

Cave paintings of extinct European cave lions almost exclusively show animals with no manes, suggesting that either they were maneless,[43] or that the paintings depict lionesses as seen hunting in a group.

White lions

The white lion is not a distinct subspecies, but a special morph with a genetic condition, leucism,[20] that causes paler colouration akin to that of the white tiger; the condition is similar to melanism, which causes black panthers. They are not albinos, having normal pigmentation in the eyes and skin. White Transvaal lion (Panthera leo krugeri) individuals occasionally have been encountered in and around Kruger National Park and the adjacent Timbavati Private Game Reserve in eastern South Africa, but are more commonly found in captivity, where breeders deliberately select them. The unusual cream colour of their coats is due to a recessive allele.[68] Reportedly, they have been bred in camps in South Africa for use as trophies to be killed during canned hunts.[69]

Behaviour

.jpg)

Lions spend much of their time resting and are inactive for about 20 hours per day.[70] Although lions can be active at any time, their activity generally peaks after dusk with a period of socialising, grooming, and defecating. Intermittent bursts of activity follow through the night hours until dawn, when hunting most often takes place. They spend an average of two hours a day walking and 50 minutes eating.[71]

Group organisation

Lions are the most socially inclined of all wild felids, most of which remain quite solitary in nature. The lion is a predatory carnivore with two types of social organization. Some lions are residents, living in groups of related lionesses, their mates, and offspring. Such a group is called a pride.[72] Females form the stable social unit in a pride and do not tolerate outside females.[73] Membership only changes with the births and deaths of lionesses,[74] although some females do leave and become nomadic.[75] Although extremely large prides, consisting of up to 30 individuals, have been observed, the average pride consists of five or six females, their cubs of both sexes, and one or two males (known as a coalition if more than one) who mate with the adult females. The number of adult males in a coalition is usually two but may increase to as many as four before decreasing again over time.[75] The sole exception to this pattern is the Tsavo lion pride which always has just one adult male.[76] Male cubs are excluded from their maternal pride when they reach maturity at around 2–3 years of age.[75] The second organizational behaviour is labeled nomads, who range widely and move about sporadically, either singularly or in pairs.[72] Pairs are more frequent among related males who have been excluded from their birth pride. Note that a lion may switch lifestyles; nomads may become residents and vice versa. Males, as a rule, live at least some portion of their lives as nomads, and some are never able to join another pride. A female who becomes a nomad has much greater difficulty joining a new pride, as the females in a pride are related, and they reject most attempts by an unrelated female to join their family group.

The area a pride occupies is called a pride area, whereas that by a nomad is a range.[72] The males associated with a pride tend to stay on the fringes, patrolling their territory. Why sociality – the most pronounced in any cat species – has developed in lionesses is the subject of much debate. Increased hunting success appears an obvious reason, but this is less than sure upon examination: coordinated hunting does allow for more successful predation but also ensures that non-hunting members reduce per capita calorific intake; however, some take a role raising cubs, who may be left alone for extended periods of time. Members of the pride regularly tend to play the same role in hunts and hone their skills. The health of the hunters is the primary need for the survival of the pride, and they are the first to consume the prey at the site it is taken. Other benefits include possible kin selection (better to share food with a related lion than with a stranger), protection of the young, maintenance of territory, and individual insurance against injury and hunger.[29]

Lionesses do most of the hunting for their pride. They are more effective hunters, as they are smaller, swifter, and more agile than the males and unencumbered by the heavy and conspicuous mane, which causes overheating during exertion. They act as a coordinated group with members who perform the same role consistently in order to stalk and bring down the prey successfully. Smaller prey is eaten at the location of the hunt, thereby being shared among the hunters; when the kill is larger it often is dragged to the pride area. There is more sharing of larger kills,[77] although pride members often behave aggressively toward each other as each tries to consume as much food as possible. Near the conclusion of the hunt, males have a tendency to dominate the kill once the lionesses have succeeded. They are more likely to share this with the cubs than with the lionesses, but males rarely share food they have killed by themselves.

Both males and females can defend the pride against intruders, but the male lion is better-suited for this purpose due to its stockier, more powerful build.[78] Some individuals consistently lead the defence against intruders, while others lag behind.[79] Lions tend to assume specific roles in the pride. Those lagging behind may provide other valuable services to the group.[80] An alternative hypothesis is that there is some reward associated with being a leader who fends off intruders, and the rank of lionesses in the pride is reflected in these responses.[81] The male or males associated with the pride must defend their relationship to the pride from outside males who attempt to take over their relationship with the pride.

Hunting and diet

Lions prefer to scavenge when the opportunity presents itself[82] with carrion providing more than 50% of their diet.[83] They scavenge animals either dead from natural causes (disease) or killed by other predators, and keep a constant lookout for circling vultures, being keenly aware that they indicate an animal dead or in distress.[82] In fact, most dead prey on which both hyenas and lions feed upon are killed by the hyenas instead of the lions.[4]

The lionesses do most of the hunting for the pride. The male lion associated with the pride usually stays and watches over young cubs until the lionesses return from the hunt. Typically, several work together and encircle the herd from different points. Once they have closed in on the herd, they usually target the animal closest to them. The attack is short and powerful; they attempt to catch the victim with a fast rush and final leap. The prey usually is killed by strangulation,[84] which can cause cerebral ischemia or asphyxia (which results in hypoxemic, or "general", hypoxia). The prey also may be killed by the lion enclosing the animal's mouth and nostrils in its jaws (which would also result in asphyxia).[4]

Lions usually hunt in coordinated groups and stalk their chosen prey. However, they are not particularly known for their stamina – for instance, a lioness' heart makes up only 0.57% of her body weight (a male's is about 0.45% of his body weight), whereas a hyena's heart is close to 1% of its body weight.[85] Thus, they only run fast in short bursts,[86] and need to be close to their prey before starting the attack. They take advantage of factors that reduce visibility; many kills take place near some form of cover or at night.[87] They sneak up to the victim until they reach a distance of approximately 30 metres (98 feet) or less.

The prey consists mainly of medium-sized mammals, with a preference for wildebeest, zebras, buffalo, and warthogs in Africa and nilgai, wild boar, and several deer species in India. Many other species are hunted, based on availability, mainly ungulates weighing between 50 and 300 kg (110 and 660 lb) such as kudu, hartebeest, gemsbok, and eland.[4] Occasionally, they take relatively small species such as Thomson's gazelle or springbok. Lions hunting in groups are capable of taking down most animals, even healthy adults, but in most parts of their range they rarely attack very large prey such as fully grown male giraffes due to the danger of injury. Giraffes and buffaloes are almost invulnerable to a solitary lion as well.[88]

Extensive studies show that lionesses normally prey on mammals with an average weight of 126 kg (278 lb), while kills made by male lions average 399 kg (880 lb).[89] In Africa, wildebeest rank at the top of preferred prey (making nearly half of the lion prey in the Serengeti) followed by zebra.[90] Lions do not prey on fully grown adult elephants; most adult hippopotamuses, rhinoceroses, and smaller gazelles, impala, and other agile antelopes are generally excluded. However, giraffes and buffaloes are often taken in certain regions. For instance, in Kruger National Park, giraffes are regularly hunted.[91] In Manyara Park, Cape buffaloes constitute as much as 62% of the lion's diet,[92] due to the high number density of buffaloes. Occasionally hippopotamus is also taken, but adult rhinoceroses are generally avoided. Warthogs are often taken depending on availability.[93] The lions of Savuti, Botswana, have adapted to hunting young elephants during the dry season, and a pride of 30 lions has been recorded killing individuals between the ages of four and eleven years.[94] In the Kalahari desert in South Africa, black-maned lions may chase baboons up a tree, wait patiently, then attack them when they try to escape:

Lions also attack domestic livestock and in India cattle contribute significantly to their diet.[64] Lions are capable of killing other predators such as leopards, cheetahs, hyenas, and wild dogs, though (unlike most felids) they seldom devour the competitors after killing them. A lion may gorge itself and eat up to 30 kg (66 lb) in one sitting;[95] if it is unable to consume all the kill it will rest for a few hours before consuming more. On a hot day, the pride may retreat to shade leaving a male or two to stand guard.[96] As revealed by fossil evidence at Olduvai, Tanzania, lions will occasionally drag their carcasses to a more sheltered spot to eat (as tigers and leopards are known to do), allowing them to consume more of a carcass without interference from scavengers.[97] An adult lioness requires an average of about 5 kg (11 lb) of meat per day, a male about 7 kg (15 lb).[98]

Because lionesses hunt in open spaces where they are easily seen by their prey, cooperative hunting increases the likelihood of a successful hunt; this is especially true with larger species. Teamwork also enables them to defend their kills more easily against other large predators such as hyenas, which may be attracted by vultures from kilometres away in open savannas. Lionesses do most of the hunting; males attached to prides do not usually participate in hunting, except in the case of larger quarry such as giraffe and buffalo. In typical hunts, each lioness has a favoured position in the group, either stalking prey on the "wing" then attacking, or moving a smaller distance in the centre of the group and capturing prey in flight from other lionesses.[99] There is evidence that male lions are just as successful at hunting as females; they are solo hunters who ambush prey in small bush.[100] Young lions first display stalking behaviour around three months of age, although they do not participate in hunting until they are almost a year old. They begin to hunt effectively when nearing the age of two.[101]

Predator competition

Lions and spotted hyenas occupy the same ecological niche, meaning they compete for prey and carrion in the areas where they coexist. A review of data across several studies indicates a dietary overlap of 58.6%.[102] Lions typically ignore spotted hyenas unless the lions are on a kill or are being harassed by the hyenas, while the latter tend to visibly react to the presence of lions whether there is food or not. Lions seize the kills of spotted hyenas: in the Ngorongoro crater, it is common for lions to subsist largely on kills stolen from hyenas, causing the hyenas to increase their kill rate.[103] On the other hand, in Northern Botswana's Chobe National Park, the situation is reversed: hyenas frequently challenge lions and steal their kills: they obtain food from 63% of all lion kills.[104] When confronted on a kill by lions, spotted hyenas may either leave or wait patiently at a distance of 30–100 m (98–328 ft) until the lions have finished,[105] but they are also bold enough to feed alongside lions, and even force the lions off a kill. The two species may attack one another even when there is no food involved for no apparent reason.[106][107] Lion predation can account for up to 71% of hyena deaths in Etosha. Spotted hyenas have adapted by frequently mobbing lions that enter their territories.[108] Experiments on captive spotted hyenas revealed that specimens with no prior experience with lions act indifferently to the sight of them, but will react fearfully to the scent.[103] The size of male lions allows them occasionally to confront hyenas in otherwise evenly matched brawls and so to tip the balance in favour of the lions.

Lions tend to dominate smaller felines such as cheetahs and leopards where they co-occur, stealing their kills and killing their cubs and even adults when given the chance. The cheetah has a 50% chance of losing its kill to lions or other predators.[109] Lions are major killers of cheetah cubs, up to 90% of which are lost in their first weeks of life due to attacks by other predators. Cheetahs avoid competition by hunting at different times of the day and hide their cubs in thick brush. Leopards also use such tactics, but have the advantage of being able to subsist much better on small prey than either lions or cheetahs. Also, unlike cheetahs, leopards can climb trees and use them to keep their cubs and kills away from lions; however, lionesses will occasionally be successful in climbing to retrieve leopard kills.[110] Similarly, lions dominate African wild dogs, not only taking their kills but also preying on young and (rarely) adult dogs. Population densities of wild dogs are low in areas where lions are more abundant.[111] However, there are a few reported cases of old and wounded lions falling prey to wild dogs.[91][112]

The Nile crocodile is the only sympatric predator (besides humans) that can singly threaten the lion. Depending on the size of the crocodile and the lion, either can lose kills or carrion to the other. Lions have been known to kill crocodiles venturing onto land,[113] while the reverse is true for lions entering waterways, as evidenced by the occasional lion claw found in crocodile stomachs.[114]

Man-eating

While lions do not usually hunt people, some (usually males) seem to seek out human prey; one well-publicised case includes the Tsavo maneaters, where 28 officially recorded railway workers building the Kenya-Uganda Railway were taken by lions over nine months during the construction of a bridge over the Tsavo River in Kenya in 1898.[115] The hunter who killed the lions wrote a book detailing the animals' predatory behaviour. The lions were larger than normal, lacked manes, and one seemed to suffer from tooth decay. The infirmity theory, including tooth decay, is not favoured by all researchers; an analysis of teeth and jaws of man-eating lions in museum collections suggests that while tooth decay may explain some incidents, prey depletion in human-dominated areas is a more likely cause of lion predation on humans.[116]

In their analysis of Tsavo and general man-eating, Kerbis Peterhans and Gnoske acknowledge that sick or injured animals may be more prone to man-eating, but that the behaviour is "not unusual, nor necessarily 'aberrant'" where the opportunity exists; if inducements such as access to livestock or human corpses are present, lions will regularly prey upon human beings. The authors note that the relationship is well-attested among other pantherines and primates in the paleontological record.[117]

The lion's proclivity for man-eating has been systematically examined. American and Tanzanian scientists report that man-eating behaviour in rural areas of Tanzania increased greatly from 1990 to 2005. At least 563 villagers were attacked and many eaten over this period – a number far exceeding the more famed "Tsavo" incidents of a century earlier. The incidents occurred near Selous National Park in Rufiji District and in Lindi Province near the Mozambican border. While the expansion of villagers into bush country is one concern, the authors argue that conservation policy must mitigate the danger because, in this case, conservation contributes directly to human deaths. Cases in Lindi have been documented where lions seize humans from the center of substantial villages.[118] Another study of 1,000 people attacked by lions in southern Tanzania between 1988 and 2009 found that the weeks following the full moon (when there was less moonlight) were a strong indicator of increased night attacks on people.[119]

Author Robert R. Frump wrote in The Man-eaters of Eden that Mozambican refugees regularly crossing Kruger National Park at night in South Africa are attacked and eaten by the lions; park officials have conceded that man-eating is a problem there. Frump believes thousands may have been killed in the decades after apartheid sealed the park and forced the refugees to cross the park at night. For nearly a century before the border was sealed, Mozambicans had regularly walked across the park in daytime with little harm.[120]

Packer estimates more than 200 Tanzanians are killed each year by lions, crocodiles, elephants, hippos, and snakes, and that the numbers could be double that amount, with lions thought to kill at least 70 of those. Packer has documented that between 1990 and 2004, lions attacked 815 people in Tanzania, killing 563. Packer and Ikanda are among the few conservationists who believe western conservation efforts must take account of these matters not just because of ethical concerns about human life, but also for the long term success of conservation efforts and lion preservation.[118]

A man-eating lion was killed by game scouts in Southern Tanzania in April 2004. It is believed to have killed and eaten at least 35 people in a series of incidents covering several villages in the Rufiji Delta coastal region.[121] Dr Rolf D. Baldus, the GTZ wildlife programme coordinator, commented that it was likely that the lion preyed on humans because it had a large abscess underneath a molar that was cracked in several places. He further commented that "This lion probably experienced a lot of pain, particularly when it was chewing."[122] GTZ is the German development cooperation agency and has been working with the Tanzanian government on wildlife conservation for nearly two decades. As in other cases this lion was large, lacked a mane, and had a tooth problem.

The "All-Africa" record of man-eating generally is considered to be not Tsavo, but incidents in the early 1930s through the late 1940s in what was then Tanganyika (now Tanzania). George Rushby, game warden and professional hunter, eventually dispatched the pride, which over three generations is thought to have killed and eaten 1,500 to 2,000 people in what is now Njombe district.[123]

Reproduction and life cycle

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mating lions. |

Most lionesses will have reproduced by the time they are four years of age.[124] Lions do not mate at any specific time of year, and the females are polyestrous.[125] As with other cats' penises, the male lion's penis has spines that point backward. During withdrawal of the penis, the spines rake the walls of the female's vagina, which may cause ovulation.[126] A lioness may mate with more than one male when she is in heat.[127]

The average gestation period is around 110 days,[125] the female giving birth to a litter of one to four cubs in a secluded den (which may be a thicket, a reed-bed, a cave, or some other sheltered area) usually away from the rest of the pride. She will often hunt by herself while the cubs are still helpless, staying relatively close to the thicket or den where the cubs are kept.[128] The cubs themselves are born blind – their eyes do not open until roughly a week after birth. They weigh 1.2–2.1 kg (2.6–4.6 lb) at birth and are almost helpless, beginning to crawl a day or two after birth and walking around three weeks of age.[129] The lioness moves her cubs to a new den site several times a month, carrying them one by one by the nape of the neck, to prevent scent from building up at a single den site and thus avoiding the attention of predators that may harm the cubs.[128]

Usually, the mother does not integrate herself and her cubs back into the pride until the cubs are six to eight weeks old.[128] Sometimes this introduction to pride life occurs earlier, however, particularly if other lionesses have given birth at about the same time. For instance, lionesses in a pride often synchronise their reproductive cycles so that they cooperate in the raising and suckling of the young (once the cubs are past the initial stage of isolation with their mother), who suckle indiscriminately from any or all of the nursing females in the pride. In addition to greater protection, the synchronization of births also has an advantage in that the cubs end up being roughly the same size, and thus have an equal chance of survival. If one lioness gives birth to a litter of cubs a couple of months after another lioness, for instance, then the younger cubs, being much smaller than their older brethren, usually are dominated by larger cubs at mealtimes – consequently, death by starvation is more common among the younger cubs.

In addition to starvation, cubs also face many other dangers, such as predation by jackals, hyenas, leopards, martial eagles, and snakes. Even buffaloes, should they catch the scent of lion cubs, often stampede toward the thicket or den where they are being kept, doing their best to trample the cubs to death while warding off the lioness. Furthermore, when one or more new males oust the previous male(s) associated with a pride, the conqueror(s) often kill any existing young cubs,[130] perhaps because females do not become fertile and receptive until their cubs mature or die. All in all, as many as 80% of the cubs will die before the age of two.[131]

Mating

Mating A pregnant lioness (right)

A pregnant lioness (right) A tolerant black-maned male

A tolerant black-maned male

When first introduced to the rest of the pride, the cubs initially lack confidence when confronted with adult lions other than their mother. They soon begin to immerse themselves in the pride life, however, playing among themselves or attempting to initiate play with the adults. Lionesses with cubs of their own are more likely to be tolerant of another lioness's cubs than lionesses without cubs. The tolerance of the male lions toward the cubs varies – sometimes, a male will patiently let the cubs play with his tail or his mane, whereas another may snarl and bat the cubs away.[132]

Weaning occurs after six to seven months. Male lions reach maturity at about 3 years of age and, at 4–5 years of age, are capable of challenging and displacing the adult male(s) associated with another pride. They begin to age and weaken between 10 and 15 years of age at the latest,[133] if they have not already been critically injured while defending the pride (once ousted from a pride by rival males, male lions rarely manage a second take-over). This leaves a short window for their own offspring to be born and mature. If they are able to procreate as soon as they take over a pride, potentially, they may have more offspring reaching maturity before they also are displaced. A lioness often will attempt to defend her cubs fiercely from a usurping male, but such actions are rarely successful. He usually kills all of the existing cubs who are less than two years old. A lioness is weaker and much lighter than a male; success is more likely when a group of three or four mothers within a pride join forces against one male.[130]

Contrary to popular belief, it is not only males that are ousted from their pride to become nomads, although most females certainly do remain with their birth pride. However, when the pride becomes too large, the next generation of female cubs may be forced to leave to eke out their own territory. Furthermore, when a new male lion takes over the pride, subadult lions, both male and female, may be evicted.[134] Life is harsh for a female nomad. Nomadic lionesses rarely manage to raise their cubs to maturity, without the protection of other pride members.

Canadian researcher Bruce Bagemihl reports that both males and females may interact homosexually. Lions are shown to be involved in group homosexual and courtship activities. Male lions will also head rub and roll around with each other before simulating sex together.[135]

Health

Although adult lions have no natural predators, evidence suggests that the majority die violently from humans or other lions.[136] Lions often inflict serious injuries on each other, either members of different prides encountering each other in territorial disputes, or members of the same pride fighting at a kill.[137] Crippled lions and lion cubs may fall victim to hyenas, leopards, or be trampled by buffalo or elephants, and careless lions may be maimed when hunting prey.[138]

Various species of tick commonly infest the ears, neck and groin regions of most lions.[139][140] Adult forms of several species of the tapeworm genus Taenia have been isolated from intestines, the lions having ingested larval forms from antelope meat.[141] Lions in the Ngorongoro Crater were afflicted by an outbreak of stable fly (Stomoxys calcitrans) in 1962; this resulted in lions becoming covered in bloody bare patches and emaciated. Lions sought unsuccessfully to evade the biting flies by climbing trees or crawling into hyena burrows; many perished or emigrated as the population dropped from 70 to 15 individuals.[142] A more recent outbreak in 2001 killed six lions.[143] Lions, especially in captivity, are vulnerable to the canine distemper virus (CDV), feline immunodeficiency virus (FIV), and feline infectious peritonitis (FIP).[20] CDV is spread through domestic dogs and other carnivores; a 1994 outbreak in Serengeti National Park resulted in many lions developing neurological symptoms such as seizures. During the outbreak, several lions died from pneumonia and encephalitis.[144] FIV, which is similar to HIV while not known to adversely affect lions, is worrisome enough in its effect in domestic cats that the Species Survival Plan recommends systematic testing in captive lions. It occurs with high to endemic frequency in several wild lion populations, but is mostly absent from Asiatic and Namibian lions.[20]

Communication

When resting, lion socialisation occurs through a number of behaviours, and the animal's expressive movements are highly developed. The most common peaceful tactile gestures are head rubbing and social licking,[145] which have been compared with grooming in primates.[146] Head rubbing – nuzzling one's forehead, face and neck against another lion – appears to be a form of greeting,[147] as it is seen often after an animal has been apart from others, or after a fight or confrontation. Males tend to rub other males, while cubs and females rub females.[148] Social licking often occurs in tandem with head rubbing; it is generally mutual and the recipient appears to express pleasure. The head and neck are the most common parts of the body licked, which may have arisen out of utility, as a lion cannot lick these areas individually.[149]

|

Lion roar

A lion in captivity roaring |

| Problems playing this file? See media help. | |

Lions have an array of facial expressions and body postures that serve as visual gestures.[150] Their repertoire of vocalisations is also large; variations in intensity and pitch, rather than discrete signals, appear central to communication. Most lion vocals are variations of growling/snarling, miaowing and roaring. Other sounds produced include purring, puffing, bleating and humming.[151] Lions tend to roar in a very characteristic manner, starting with a few deep, long roars that trail off into a series of shorter ones.[152][153] They most often roar at night; the sound, which can be heard from a distance of 8 kilometres (5.0 mi), is used to advertise the animal's presence.[151] Lions have the loudest roar of any big cat.

Distribution and habitat

In Africa, lions can be found in savanna grasslands with scattered Acacia trees, which serve as shade;[155] their habitat in India is a mixture of dry savanna forest and very dry deciduous scrub forest.[156] The habitat of lions originally spanned the southern parts of Eurasia, ranging from Greece to India, and most of Africa except the central rainforest-zone and the Sahara desert. Herodotus reported that lions had been common in Greece in 480 BC; they attacked the baggage camels of the Persian king Xerxes on his march through the country. Aristotle considered them rare by 300 BC. By 100 AD they were extirpated.[157] A population of Asiatic lions survived until the tenth century in the Caucasus, their last European outpost.[158]

The species was eradicated from Palestine by the Middle Ages and from most of the rest of Asia after the arrival of readily available firearms in the eighteenth century. Between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, they became extinct in North Africa and Southwest Asia. By the late nineteenth century, the lion had disappeared from Turkey and most of northern India,[20][159] while the last sighting of a live Asiatic lion in Iran was in 1941 (between Shiraz and Jahrom, Fars Province), although the corpse of a lioness was found on the banks of the Karun river, Khūzestān Province in 1944. There are no subsequent reliable reports from Iran.[95] The subspecies now survives only in and around the Gir Forest of northwestern India.[34] Approximately 500 lions live in the area of the 1,412 km2 (545 sq mi) sanctuary in the state of Gujarat, which covers most of the forest. Their numbers have increased from 180 to 523 animals mainly because the natural prey species have recovered.[35][160]

Population and conservation status

Most lions now live in eastern and southern Africa, and their numbers there are rapidly decreasing, with an estimated 30–50% decline per 20 years in the late half of the twentieth century.[2] Estimates of the African lion population range between 16,500 and 47,000 living in the wild in 2002–2004,[162][163] down from early 1990s estimates that ranged as high as 100,000 and perhaps 400,000 in 1950. Primary causes of the decline include disease and human interference.[2] Habitat loss and conflicts with humans are considered the most significant threats to the species.[164][165] The remaining populations are often geographically isolated from one another, which can lead to inbreeding, and consequently, reduced genetic diversity. Therefore, the lion is considered a vulnerable species by the International Union for Conservation of Nature, while the Asiatic subspecies is endangered.[166] The lion population in the region of West Africa is isolated from lion populations of Central Africa, with little or no exchange of breeding individuals. The number of mature individuals in West Africa is estimated by two separate recent surveys at 850–1,160 (2002/2004). There is disagreement over the size of the largest individual population in West Africa: the estimates range from 100 to 400 lions in Burkina Faso's Arly-Singou ecosystem.[2] Another population in northwestern Africa is found in Waza National Park, where approximately 14–21 animals persist.[167]

_-_Male_lion_Sotik_Plains_May_1909.png)

Conservation of both African and Asian lions has required the setup and maintenance of national parks and game reserves; among the best known are Etosha National Park in Namibia, Serengeti National Park in Tanzania, and Kruger National Park in eastern South Africa. The Ewaso Lions Project protects lions in the Samburu National Reserve, Buffalo Springs National Reserve and Shaba National Reserve of the Ewaso Ng'iro ecosystem in Northern Kenya.[168] Outside these areas, the issues arising from lions' interaction with livestock and people usually results in the elimination of the lions.[169] In India, the last refuge of the Asiatic lion is the 1,412 km2 (545 sq mi) Gir Forest National Park in western India, which had approximately 180 lions in 1974 and about 400 in 2010.[35] As in Africa, numerous human habitations are close by with the resultant problems between lions, livestock, locals and wildlife officials.[170] The establishment of a second independent population of Asiatic lions is planned at the Kuno Wildlife Sanctuary in the Indian state of Madhya Pradesh.[171]

The former popularity of the Barbary lion as a zoo animal has meant that scattered lions in captivity are likely to be descended from Barbary lion stock. This includes lions at Port Lympne Wild Animal Park in Kent, England that are descended from animals owned by the King of Morocco.[172] Another eleven animals believed to be Barbary lions were found in Addis Ababa zoo, descendants of animals owned by Emperor Haile Selassie. WildLink International, in collaboration with Oxford University, launched their ambitious International Barbary Lion Project with the aim of identifying and breeding Barbary lions in captivity for eventual reintroduction into a national park in the Atlas Mountains of Morocco.[63]

Following the discovery of the decline of lion population in Africa, several coordinated efforts involving lion conservation have been organised in an attempt to stem this decline. Lions are one species included in the Species Survival Plan, a coordinated attempt by the Association of Zoos and Aquariums to increase its chances of survival. The plan was originally started in 1982 for the Asiatic lion, but was suspended when it was found that most Asiatic lions in North American zoos were not genetically pure, having been hybridised with African lions. The African lion plan started in 1993, focusing especially on the South African subspecies, although there are difficulties in assessing the genetic diversity of captive lions, since most individuals are of unknown origin, making maintenance of genetic diversity a problem.[20]

In 2015, a population of lions that was previously believed extirpated was filmed in the Alatash National Park, Ethiopia, close to the Sudanese border. This population may possibly number up to 200 animals.[173][174]

In captivity

.jpg)

Lions are part of a group of exotic animals that are the core of zoo exhibits since the late eighteenth century; members of this group are invariably large vertebrates and include elephants, rhinoceroses, hippopotamuses, large primates, and other big cats; zoos sought to gather as many of these species as possible.[175] Although many modern zoos are more selective about their exhibits,[176] there are more than 1,000 African and 100 Asiatic lions in zoos and wildlife parks around the world. They are considered an ambassador species and are kept for tourism, education and conservation purposes.[177] Lions can reach an age of over 20 years in captivity; Apollo, a resident lion of Honolulu Zoo in Honolulu, Hawaii, died at age 22 in August 2007. His two sisters, born in 1986, were still alive in August 2007.[178] Breeding programs need to note origins to avoid breeding different subspecies and thus reducing conservation value.[179] However, several Asiatic-African lion crosses have been bred.[180]

At the ancient Egyptian cities of Taremu and Per-Bast were temples to the lioness goddesses of Egypt, Sekhmet and Bast and at Taremu there was a temple to the son of the deity, Maahes the lion prince, where live lions were kept and allowed to roam within his temple. The Greeks called the city Leontopolis, the "City of Lions" and documented that practice. Lions were kept and bred by Assyrian kings as early as 850 BC,[157] and Alexander the Great was said to have been presented with tame lions by the Malhi of northern India.[181] Later in Roman times, lions were kept by emperors to take part in the gladiator arenas or for executions (see bestiarii, damnatio ad bestias, and venatio). Roman notables, including Sulla, Pompey, and Julius Caesar, often ordered the mass slaughter of hundreds of lions at a time.[182] In the East, lions were tamed by Indian princes, and Marco Polo reported that Kublai Khan kept lions inside.[183] The first European "zoos" spread among noble and royal families in the thirteenth century, and until the seventeenth century were called seraglios; at that time, they came to be called menageries, an extension of the cabinet of curiosities. They spread from France and Italy during the Renaissance to the rest of Europe.[184] In England, although the seraglio tradition was less developed, lions were kept at the Tower of London in a seraglio established by King John in the thirteenth century,[185][186] probably stocked with animals from an earlier menagerie started in 1125 by Henry I at his hunting lodge in Woodstock, near Oxford; where lions had been stocked according to William of Malmesbury.[187]

Seraglios served as expressions of the nobility's power and wealth. Animals such as big cats and elephants, in particular, symbolised power, and would be pitted in fights against each other or domesticated animals. By extension, menageries and seraglios served as demonstrations of the dominance of humanity over nature. Consequently, the defeat of such natural "lords" by a cow in 1682 astonished the spectators, and the flight of an elephant before a rhinoceros drew jeers. Such fights would slowly fade out in the seventeenth century with the spread of the menagerie and their appropriation by the commoners. The tradition of keeping big cats as pets would last into the nineteenth century, at which time it was seen as highly eccentric.[188]

The presence of lions at the Tower of London was intermittent, being restocked when a monarch or his consort, such as Margaret of Anjou the wife of Henry VI, either sought or were given animals. Records indicate they were kept in poor conditions there in the seventeenth century, in contrast to more open conditions in Florence at the time.[189] The menagerie was open to the public by the eighteenth century; admission was a sum of three half-pence or the supply of a cat or dog for feeding to the lions.[190] A rival menagerie at the Exeter Exchange also exhibited lions until the early nineteenth century.[191] The Tower menagerie was closed down by William IV,[190] and animals transferred to the London Zoo, which opened its gates to the public on 27 April 1828.[192]

The wild animals trade flourished alongside improved colonial trade of the nineteenth century. Lions were considered fairly common and inexpensive. Although they would barter higher than tigers, they were less costly than larger, or more difficult to transport animals such as the giraffe and hippopotamus, and much less than giant pandas.[193] Like other animals, lions were seen as little more than a natural, boundless commodity that was mercilessly exploited with terrible losses in capture and transportation.[194] The widely reproduced imagery of the heroic hunter chasing lions would dominate a large part of the century.[195] Explorers and hunters exploited a popular Manichean division of animals into "good" and "evil" to add thrilling value to their adventures, casting themselves as heroic figures. This resulted in big cats, always suspected of being man-eaters, representing "both the fear of nature and the satisfaction of having overcome it."[196]

Lions were kept in cramped and squalid conditions at London Zoo until a larger lion house with roomier cages was built in the 1870s.[197] Further changes took place in the early twentieth century, when Carl Hagenbeck designed enclosures more closely resembling a natural habitat, with concrete 'rocks', more open space and a moat instead of bars. He designed lion enclosures for both Melbourne Zoo and Sydney's Taronga Zoo, among others, in the early twentieth century. Though his designs were popular, the old bars and cage enclosures prevailed until the 1960s in many zoos.[198] In the later decades of the twentieth century, larger, more natural enclosures and the use of wire mesh or laminated glass instead of lowered dens allowed visitors to come closer than ever to the animals, with some attractions even placing the den on ground higher than visitors, such as the Cat Forest/Lion Overlook of Oklahoma City Zoological Park.[20] Lions are now housed in much larger naturalistic areas; modern recommended guidelines more closely approximate conditions in the wild with closer attention to the lions' needs, highlighting the need for dens in separate areas, elevated positions in both sun and shade where lions can sit and adequate ground cover and drainage as well as sufficient space to roam. There have also been instances where a lion was kept by a private individual, such as the lioness Elsa, who was raised by George Adamson and his wife Joy Adamson and came to develop a strong bond with them, particularly the latter. The lioness later achieved fame, her life being documented in a series of books and films.

Baiting and taming

.jpg)

Lion-baiting is a blood sport involving the baiting of lions in combat with other animals, usually dogs. Records of it exist in ancient times through until the seventeenth century. It was finally banned in Vienna by 1800 and England in 1835.[199][200]

Lion taming refers to the practice of taming lions for entertainment, either as part of an established circus or as an individual act, such as Siegfried & Roy. The term is also often used for the taming and display of other big cats such as tigers, leopards, and cougars. The practice was pioneered in the first half of the nineteenth century by Frenchman Henri Martin and American Isaac Van Amburgh who both toured widely, and whose techniques were copied by a number of followers.[201] Van Amburgh performed before Queen Victoria in 1838 when he toured Great Britain. Martin composed a pantomime titled Les Lions de Mysore ("the lions of Mysore"), an idea that Amburgh quickly borrowed. These acts eclipsed equestrianism acts as the central display of circus shows, but truly entered public consciousness in the early twentieth century with cinema. In demonstrating the superiority of human over animal, lion taming served a purpose similar to animal fights of previous centuries.[201] The ultimate proof of a tamer's dominance and control over a lion is demonstrated by placing his head in the lion's mouth. The now iconic lion tamer's chair was possibly first used by American Clyde Beatty (1903–1965).[202]

Cultural significance

.jpg)

The lion has been an icon for humanity for thousands of years, appearing in cultures across Europe, Asia, and Africa. Despite incidents of attacks on humans, lions have enjoyed a positive depiction in culture as strong and noble. A common depiction is their representation as "king of the jungle" or "king of beasts"; hence, the lion has been a popular symbol of royalty and stateliness,[203] as well as a symbol of bravery; it is featured in several fables of the sixth century BC Greek storyteller Aesop.[204]

Representations of lions date back to the early Upper Paleolithic. The lioness-headed ivory carving from Vogelherd cave in the Swabian Alb in southwestern Germany, dubbed Löwenmensch (lion-human) in German. The sculpture has been determined to be at least 32,000 years old from the Aurignacian culture,[19] but it may date to as early as 40,000 years ago.[205] The sculpture has been interpreted as anthropomorphic, giving human characteristics to an animal, however, it also may represent a deity. Two lions were depicted mating in the Chamber of Felines in 15,000-year-old Paleolithic cave paintings in the Lascaux caves. Cave lions also are depicted in the Chauvet Cave, discovered in 1994; this has been dated at 32,000 years of age,[42] though it may be of similar or younger age to Lascaux.[206]

In Africa, cultural views of the lion have varied by region. In some cultures, the lion symbolises power and royalty and some powerful rulers had the word "lion" in their nickname. For example, Marijata of the Mali Empire (c. 1235–c. 1600) was given the name "Lion of Mali".[207] Njaay, the legendary founder of the Waalo kingdom (1287–1855), is said to have been raised by lions and returned to his people part-lion to unite them using the knowledge he learned from the beasts. In much of West Africa, to be compared to a lion was considered to be one of the greatest compliments. The social hierarchies of their societies where connected to the animal kingdom and the lion represented the top class. In parts of West and East Africa, the lion is associated with healing and is seen as the link between the seers and the supernatural. In other East African traditions, the lion is the symbol of laziness.[208] In many folktales, lions are portrayed as having low intelligence and are easily tricked by other animals.[207]

Ancient Egypt venerated the lioness (the fierce hunter) as their war deities and among those in the Egyptian pantheon are, Bast, Mafdet, Menhit, Pakhet, Sekhmet, Tefnut, and the Sphinx;[203] The Nemean lion was symbolic in Ancient Greece and Rome, represented as the constellation and zodiac sign Leo, and described in mythology, where its skin was borne by the hero Heracles.[209]

The lion was a prominent symbol in ancient Mesopotamia (from Sumer up to Assyrian and Babylonian times), where it was strongly associated with kingship.[210] The classic Babylonian lion motif, found as a statue, carved or painted on walls, is often referred to as the striding lion of Babylon. It is in Babylon that the biblical Daniel is said to have been delivered from the lion's den.[211] The Lion Hunt of Ashurbanipal is a famous sequence of Assyrian palace reliefs from c. 640 BC, now in the British Museum.

In the Talmud, Chullin 59b, Rabbi Joshua ben Hananiah tells Emperor Hadrian about the giant lion of the forest of Bei Ilai called the Tigris, a lion so huge that the space between its ears measures 9 cubits. The emperor asks the rabbi to call forth this lion. He reluctantly agrees. At a distance of 400 parasangs from Rome it roars, and all pregnant women miscarry and all the walls of Rome fall down. Then it comes to 300 parasangs and roars, and all the front teeth and molars of Roman men fall out, and even the emperor himself falls from his throne. He begs the rabbi to send it back. The rabbi prays and it returns to its place.

In the Puranic texts of Hinduism, Narasimha ("man-lion") a half-lion, half-man incarnation or (avatar) of Vishnu, is worshipped by his devotees and saved the child devotee Prahlada from his father, the evil demon king Hiranyakashipu;[212] Vishnu takes the form of half-man/half-lion, in Narasimha, having a human torso and lower body, but with a lion-like face and claws.[213] Singh is an ancient Indian vedic name meaning "lion" (Asiatic lion), dating back over 2000 years to ancient India. It was originally only used by Rajputs a Hindu Kshatriya or military caste in India. After the birth of the Khalsa brotherhood in 1699, the Sikhs also adopted the name "Singh" due to the wishes of Guru Gobind Singh. Along with millions of Hindu Rajputs today, it is also used by over 20 million Sikhs worldwide.[214] Found famously on numerous flags and coats of arms all across Asia and Europe, the Asiatic lions also stand firm on the National Emblem of India.[215] Farther south on the Indian subcontinent, the Asiatic lion is symbolic for the Sinhalese,[216] Sri Lanka's ethnic majority; the term derived from the Indo-Aryan Sinhala, meaning the "lion people" or "people with lion blood", while a sword-wielding lion is the central figure on the national flag of Sri Lanka.[217]

.jpg)

.jpg)

The Asiatic lion is a common motif in Chinese art. They were first used in art during the late Spring and Autumn period (fifth or sixth century BC), and became much more popular during the Han Dynasty (206 BC – AD 220), when imperial guardian lions started to be placed in front of imperial palaces for protection. Because lions have never been native to China, early depictions were somewhat unrealistic; after the introduction of Buddhist art to China in the Tang Dynasty (after the sixth century AD), lions usually were wingless, with shorter, thicker bodies, and curly manes.[218] The lion dance is a form of traditional dance in Chinese culture in which performers mimic a lion's movements in a lion costume, often with musical accompaniment from cymbals, drums, and gongs. They are performed at Chinese New Year, the August Moon Festival and other celebratory occasions for good luck.[219]

The island nation of Singapore derives its name from the Malay words singa (lion) and pora (city/fortress), which in turn is from the Tamil-Sanskrit சிங்க singa सिंह siṃha and पुर புர pura, which is cognate to the Greek πόλις, pólis.[220] According to the Malay Annals, this name was given by a fourteenth-century Sumatran Malay prince Sang Nila Utama, who, on alighting the island after a thunderstorm, spotted an auspicious beast on shore that appeared to be a lion.[221]

The name of the nomadic Hadendoa people, inhabiting parts of Sudan, Egypt, and Eritrea, is made up of haɖa 'lion' and (n)ɖiwa 'clan'. Other variants are Haɖai ɖiwa, Hanɖiwa, and Haɖaatʼar (children of lioness).

"Lion" was the nickname of several medieval warrior rulers with a reputation for bravery, such as the English King Richard the Lionheart,[203] Henry the Lion, (German: Heinrich der Löwe), Duke of Saxony, William the Lion, King of Scotland, and Robert III of Flanders nicknamed "The Lion of Flanders"—a major Flemish national icon up to the present. Lions are frequently depicted on coats of arms, either as a device on shields themselves, or as supporters, but the lioness is much more infrequent.[222] The formal language of heraldry, called blazon, employs French terms to describe the images precisely. Such descriptions specified whether lions or other creatures were "rampant" or "passant", that is whether they were rearing or crouching.[223] The lion is used as a symbol of sporting teams, from national association football teams such as England, Scotland and Singapore to famous clubs such as the Detroit Lions[224] of the NFL, Chelsea[225] and Aston Villa of the English Premier League,[226] (and the Premiership itself), Eintracht Braunschweig of the Bundesliga, and to a host of smaller clubs around the world.

By Joseph-Désiré Court (1841)

Lions continue to be featured in modern literature, from the messianic Aslan in The Lion, the Witch and the Wardrobe and following books from The Chronicles of Narnia series written by C. S. Lewis,[227] to the comedic Cowardly Lion in The Wonderful Wizard of Oz.[228] The advent of moving pictures saw the continued presence of lion symbolism; one of the most iconic and widely recognised lions is Leo the Lion, which has been the mascot for Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer (MGM) studios since the 1920s.[229] The 1960s saw the appearance of what is possibly the most famous lioness, the Kenyan animal Elsa in the movie Born Free,[230] based on the true-life book of the same title.[231] The lion's role as king of the beasts has been used in cartoons, such as the 1994 Disney animated feature film The Lion King.[232]

Heraldic depictions

See also

- Lion lights (lights used to repel lions)

- Tiger versus lion

References

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Bauer, H.; Packer, C.; Funston, P.F.; Henschel, P.; Nowell, K. (2016). "Panthera leo". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2016.2. International Union for Conservation of Nature.

- 1 2 3 Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae :secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. (in Latin). 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 41. Retrieved 8 September 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nowak, Ronald M. (1999). Walker's Mammals of the World. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-5789-9.

- 1 2 Harington, C. R. "Dick (1969). "Pleistocene remains of the lion-like cat (Panthera atrox) from the Yukon Territory and northern Alaska". Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences. 6 (5): 1277–88. doi:10.1139/e69-127.

- ↑ Smuts, G. L. (1982). Lion. Johannesburg: Macmillan South Africa. p. 231. ISBN 0-86954-122-6.

- ↑ Lions' nocturnal chorus. Earth-touch.com. Retrieved on 31 July 2013.

- ↑ African Lion Panthera leo. Phoenix Zoo Fact Sheet.

- ↑ Simpson, D. P. (1979). Cassell's Latin Dictionary (5th ed.). London: Cassell Ltd. p. 342. ISBN 0-304-52257-0.

- ↑ Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert (1980). A Greek-English Lexicon (Abridged Edition). United Kingdom: Oxford University Press. p. 411. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ Simpson, John; Weiner, Edmund, eds. (1989). "Lion". Oxford English Dictionary (2nd ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-861186-2.

- ↑ Johnson, W.E.; Eizirik, E.; Pecon-Slattery, J.; Murphy, W.J.; Antunes, A.; Teeling, E.; O'Brien, S.J. (2006). "The late Miocene radiation of modern Felidae: a genetic assessment". Science (New York). 311 (5757): 73–7. doi:10.1126/science.1122277. PMID 16400146.

- ↑ Werdelin, L.; Yamaguchi, N.; Johnson, W.E.; O'Brien, S.J. (2010). "Phylogeny and evolution of cats (Felidae)" (PDF). Biology and Conservation of Wild Felids: 59–82.

- ↑ Davis, B.W.; Li, G.; Murphy, W.J. (2010). "Supermatrix and species tree methods resolve phylogenetic relationships within the big cats, Panthera (Carnivora: Felidae)" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution. 56 (1): 64–76. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2010.01.036.

- ↑ Mazák, J.H.; Christiansen, P.; Kitchener, A.C.; Goswami, A. (2011). "Oldest known pantherine skull and evolution of the tiger". PLoS ONE. 6 (10): e25483. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0025483.

- ↑ Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; Cooper, Alan; Werdelin, Lars; MacDonald, David W. (August 2004). "Evolution of the mane and group-living in the lion (Panthera leo): a review". Journal of Zoology. 263 (4): 329–42. doi:10.1017/S0952836904005242.

- ↑ Turner, Allen (1997). The big cats and their fossil relatives: an illustrated guide to their evolution and natural history. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10229-1.

- ↑ Harington, C. R. (Dick) (1996). "American Lion". Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre website. Yukon Beringia Interpretive Centre. Retrieved 25 January 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Burger, Joachim; Rosendahl, Wilfried; Loreille, Odile; Hemmer, Helmut; Eriksson, Torsten; Götherström, Anders; Hiller, Jennifer; Collins, Matthew J.; Wess, Timothy; Alt, Kurt W. (2004). "Molecular phylogeny of the extinct cave lion Panthera leo spelaea" (PDF). Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution (fulltext). 30 (3): 841–49. doi:10.1016/j.ympev.2003.07.020. PMID 15012963. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grisham, Jack (2001). "Lion". In Bell, Catherine E. Encyclopedia of the World's Zoos. 2: G–P. Chofago: Fitzroy Dearborn. pp. 733–39. ISBN 1-57958-174-9.

- 1 2 3 4 Barnett, Ross; Yamaguchi, Nobuyuki; Barnes, Ian; Cooper, Alan (August 2006). "Lost populations and preserving genetic diversity in the lion Panthera leo: Implications for its ex situ conservation". Conservation Genetics. 7 (4): 507–14. doi:10.1007/s10592-005-9062-0.