Ferret

| Ferret | |

|---|---|

| |

| Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Caniformia |

| Family: | Mustelidae |

| Genus: | Mustela |

| Species: | M. putorius |

| Subspecies: | M. p. furo |

| Trinomial name | |

| Mustela putorius furo Linnaeus, 1758 | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Mustela furo Linnaeus, 1758 | |

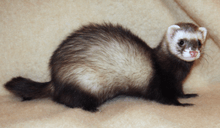

The ferret (Mustela putorius furo) is the domesticated form of the European polecat, a mammal belonging to the same genus as the weasel, Mustela of the family Mustelidae.[1] They typically have brown, black, white, or mixed fur. They have an average length of 51 cm (20 in) including a 13 cm (5.1 in) tail, weigh about 1.5–4 pounds (0.7–2 kg), and have a natural lifespan of 7 to 10 years.[2] Ferrets are sexually dimorphic predators with males being substantially larger than females.

Several other Mustelids also have the word ferret in their common names, including an endangered species, the black-footed ferret.

The history of the ferret's domestication is uncertain, like that of most other domestic animals, but it is likely that ferrets have been domesticated for at least 2,500 years. They are still used for hunting rabbits in some parts of the world, but increasingly, they are kept only as pets.

Being so closely related to polecats, ferrets easily hybridize with them, and this has occasionally resulted in feral colonies of polecat-ferret hybrids that have caused damage to native fauna, especially in New Zealand.[3] As a result, some parts of the world have imposed restrictions on the keeping of ferrets.

Etymology

The name "ferret" is derived from the Latin furittus, meaning "little thief", a likely reference to the common ferret penchant for secreting away small items.[4] The Greek word ictis occurs in a play written by Aristophanes, The Acharnians, in 425 BC. Whether this was a reference to ferrets, polecats, or the similar Egyptian mongoose is uncertain.[5]

Biology

Characteristics

Ferrets have a typical Mustelid body-shape being long and slender. Their average length is about 50 cm including a 13-cm tail. Their pelage has various colorations including brown, black, white or mixed. They weigh between 0.7 kg to 2.0 kg and are sexually dimorphic as the males are substantially larger than females. The average gestation period is 42 days and females may have 2 or 3 litters each year. The litter size is usually between 3 and 7 kits which are weaned after 3 to 6 weeks and become independent at 3 months. They become sexually mature at approximately 6 months and the average life span is 7 to 10 years.[6][7]

Behavior

Ferrets spend 14–18 hours a day asleep and are most active around the hours of dawn and dusk, meaning they are crepuscular.[8] Unlike their polecat ancestors, which are solitary animals, most ferrets will live happily in social groups. A group of ferrets is commonly referred to as a "business".[9] They are territorial, like to burrow, and prefer to sleep in an enclosed area.[10]

Like many other mustelids, ferrets have scent glands near their anus, the secretions from which are used in scent marking. Ferrets can recognize individuals from these anal gland secretions, as well as the sex of unfamiliar individuals.[11] Ferrets may also use urine marking for sex and individual recognition.[12]

As with skunks, ferrets can release their anal gland secretions when startled or scared, but the smell is much less potent and dissipates rapidly. Most pet ferrets in the US are sold de-scented (anal glands removed).[13] In many other parts of the world, including the UK and other European countries, de-scenting is considered an unnecessary mutilation.

When excited, they may perform a behaviour commonly called the weasel war dance, characterized by a frenzied series of sideways hops, leaps and bumping into nearby objects. Despite its common name, this is not aggressive but is a joyful invitation to play. It is often accompanied by a soft clucking noise, commonly referred to as "dooking".[14] In contrast, when scared, ferrets will make a hissing noise; when upset, they will make a soft 'squeaking' noise.[15]

Diet

Ferrets are obligate carnivores.[16] The natural diet of their wild ancestors consisted of whole small prey—i.e., meat, organs, bones, skin, feathers, and fur.[17] Ferrets have short digestive systems and quick metabolism, so they need to eat frequently. Prepared dry foods consisting almost entirely of meat (including high-grade cat food, although specialized ferret food is increasingly available and preferable)[18] provide the most nutritional value and are the most convenient,[19] though some ferret owners feed pre-killed or live prey (such as mice and rabbits) to their ferrets to more closely mimic their natural diet.[20][21] Ferret digestive tracts lack a cecum and the animal is largely unable to digest plant matter.[22] Before much was known about ferret physiology, many breeders and pet stores recommended food like fruit in the ferret diet, but it is now known that such foods are inappropriate, and may in fact have negative ramifications on ferret health. Ferrets imprint on their food at around six months old. This can make introducing new foods to an older ferret a challenge, and even simply changing brands of kibble may meet with resistance from a ferret that has never eaten the food as a kit. It is therefore advisable to expose young ferrets to as many different types and flavors of appropriate food as possible.[23]

Dentition

Ferrets have four types of teeth (the number includes maxillary (upper) and mandibular (lower) teeth):

- Twelve small teeth (only a couple of millimeters) located between the canines in the front of the mouth. These are known as the incisors and are used for grooming.

- Four canines used for killing prey.

- Twelve premolar teeth that the ferret uses to chew food—located at the sides of the mouth, directly behind the canines. The ferret uses these teeth to cut through flesh, using them in a scissors action to cut the meat into digestible chunks.

- Six molars (two on top and four on the bottom) at the far back of the mouth are used to crush food.

Health

Ferrets are known to suffer from several distinct health problems. Among the most common are cancers affecting the adrenal glands, pancreas, and lymphatic system. Viral diseases include canine distemper and influenza. Health problems can occur in unspayed females when not being used for breeding.[24] Certain health problems have also been linked to ferrets being neutered before reaching sexual maturity. Certain colors of ferret may also carry a genetic defect known as Waardenburg syndrome. Similar to domestic cats, ferrets can also suffer from hairballs and dental problems.

History of domestication

In common with most domestic animals, the original reason for ferrets being domesticated by human beings is uncertain, but it may have involved hunting. According to phylogenetic studies, the ferret was domesticated from the European polecat (Mustela putorius), and likely descends from a North African lineage of the species.[25] Analysis of mitochondrial DNA suggests that ferrets were domesticated around 2,500 years ago, although what appear to be ferret remains have been dated to 1500 BC.[26] It has been claimed that the ancient Egyptians were the first to domesticate ferrets, but as no mummified remains of a ferret have yet been found, or any hieroglyph of a ferret, and no polecat now occurs wild in the area, that idea seems unlikely.[27]

Ferrets were probably used by the Romans for hunting.[28][29]

Colonies of feral ferrets have established themselves in areas where there is no competition from similarly sized predators, such as in the Shetland Islands and in remote regions in New Zealand. Where ferrets coexist with polecats, hybridization is common. It has been claimed that New Zealand has the world's largest feral population of ferret-polecat hybrids.[30] In 1877, farmers in New Zealand demanded that ferrets be introduced into the country to control the rabbit population, which was also introduced by humans. Five ferrets were imported in 1879, and in 1882–1883, 32 shipments of ferrets were made from London, totaling 1,217 animals. Only 678 landed, and 198 were sent from Melbourne, Australia. On the voyage, the ferrets were mated with the European polecat, creating a number of hybrids that were capable of surviving in the wild. In 1884 and 1886, close to 4,000 ferrets and ferret hybrids, 3,099 weasels and 137 stoats were turned loose.[31] Concern was raised that these animals would eventually prey on indigenous wildlife once rabbit populations dropped, and this is exactly what happened to New Zealand's bird species which previously had had no mammalian predators.

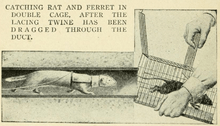

Ferreting

For millennia, the main use of ferrets was for hunting, or ferreting. With their long, lean build, and inquisitive nature, ferrets are very well equipped for getting down holes and chasing rodents, rabbits and moles out of their burrows. Caesar Augustus sent ferrets or mongooses (named "viverrae" by Plinius) to the Balearic Islands to control the rabbit plagues in 6 BC.[32][33] In England, in 1390, a law was enacted restricting the use of ferrets for hunting to the relatively wealthy:

it is ordained that no manner of layman which hath not lands to the value of forty shillings a year shall from henceforth keep any greyhound or other dog to hunt, nor shall he use ferrets, nets, heys, harepipes nor cords, nor other engines for to take or destroy deer, hares, nor conies, nor other gentlemen's game, under pain of twelve months' imprisonment.[34]

Ferrets were first introduced into the New World in the 17th century, and were used extensively from 1860 until the start of World War II to protect grain stores in the American West from rodents. They are still used for hunting in some countries, including the United Kingdom, where rabbits are considered a plague species by farmers.[35] The practice is illegal in several countries where it is feared that ferrets could unbalance the ecology. In 2009 in Finland, where ferreting was previously unknown, the city of Helsinki began to use ferrets to restrict the city's rabbit population to a manageable level. Ferreting was chosen because in populated areas it is considered to be safer and less ecologically damaging than shooting the rabbits.

Ferrets as pets

In the United States, ferrets were relatively rare pets until the 1980s. A government study by the California State Bird and Mammal Conservation Program estimated that by 1996 about 800,000 domestic ferrets were being kept as pets in the United States.[36]

Like many household pets, ferrets require a cage. For ferrets, a wire cage at least 18 inches long and deep and 30 inches wide or longer is needed. Ferrets cannot be housed in environments such as an aquarium because of the poor ventilation.[37] It is preferable that the cage have more than one level but this is not crucial. Usually 2 to 3 different shelves are used.

Regulation

- Australia – It is illegal to keep ferrets as pets in Queensland or the Northern Territory; in the ACT a licence is required.

- Brazil – They are allowed only if they are given a microchip identification tag and sterilized.

- New Zealand – It has been illegal to sell, distribute or breed ferrets in New Zealand since 2002 unless certain conditions are met.[38]

- United States – Ferrets were once banned in many US states, but most of these laws were rescinded in the 1980s and 1990s as they became popular pets. Ferrets are still illegal in California under Fish and Game Code Section 2118;[39] and the California Code of Regulations,[40] although it is not illegal for veterinarians in the state to treat ferrets kept as pets. In November 1995, ferret proponents asked the California Fish and Game Commission to remove the domesticated ferret from the restrictive wildlife list. Additionally, "Ferrets are strictly prohibited as pets under Hawaii law because they are potential carriers of the rabies virus";[41] the territory of Puerto Rico has a similar law.[42] Ferrets are restricted by individual cities, such as Washington, DC, and New York City,[42] which renewed its ban in 2015.[43][44] They are also prohibited on many military bases.[42] A permit to own a ferret is needed in other areas, including Rhode Island.[45] Illinois and Georgia do not require a permit to merely possess a ferret, but a permit is required to breed ferrets.[46][47] It was once illegal to own ferrets in Dallas, Texas,[48] but the current Dallas City Code for Animals includes regulations for the vaccination of ferrets.[49] Pet ferrets are legal in Wisconsin, however legality varies by municipality. The city of Oshkosh, for example, classifies ferrets as a wild animal and subsequently prohibits them from being kept within the city limits. Also, an import permit from the state department of agriculture is required to bring one into the state.[50] Under the Common Law, ferrets are deemed "wild animals" subject to strict liability for injuries they cause, but in several states statutory law has overruled the common law, deeming ferrets "domestic." [51]

- Japan – In Hokkaido prefecture, ferrets must be registered with the local government.[52] In other prefectures, no restrictions apply.

Other uses of ferrets

Ferrets are an important experimental animal model for human influenza,[53][54] and have been used to study the 2009 H1N1 (swine flu) virus.[55] Smith, Andrews, Laidlaw (1933) inoculated ferrets intra-nasally with human naso-pharyngeal washes, which produced a form of influenza that spread to other cage mates. The human influenza virus (Influenza type A) was transmitted from an infected ferret to a junior investigator, from whom it was subsequently re-isolated.

- Ferrets have been used in many broad areas of research, such as the study of pathogenesis and treatment in a variety of human disease, these including studies into cardiovascular disease, nutrition, respiratory diseases such as SARS and human influenza, airway physiology,[56] cystic fibrosis and gastrointestinal disease.

- Because they share many anatomical and physiological features with humans, ferrets are extensively used as experimental subjects in biomedical research, in fields such as virology, reproductive physiology, anatomy, endocrinology, and neuroscience.[57]

- In the UK, ferret racing is often a feature of rural fairs or festivals, with people placing small bets on ferrets that run set routes through pipes and wire mesh. Although financial bets are placed, the event is primarily for entertainment purposes as opposed to 'serious' betting sports such as horse or greyhound racing.[58][59]

Terminology and coloring

Male ferrets are called hobs; female ferrets are jills. A spayed female is a sprite, a neutered male is a gib, and a vasectomised male is known as a hoblet. Ferrets under one year old are known as kits. A group of ferrets is known as a "business",[60] or historically as a "busyness". Other purported collective nouns, including "besyness", "fesynes", "fesnyng", and "feamyng", appear in some dictionaries, but are almost certainly ghost words.[61]

Most ferrets are either albinos, with white fur and pink eyes, or display the typical dark masked sable coloration of their wild polecat ancestors. In recent years fancy breeders have produced a wide variety of colors and patterns. Color refers to the color of the ferret's guard hairs, undercoat, eyes, and nose; pattern refers to the concentration and distribution of color on the body, mask, and nose, as well as white markings on the head or feet when present. Some national organizations, such as the American Ferret Association, have attempted to classify these variations in their showing standards.[62]

There are four basic colors. The sable (including chocolate and dark brown), albino, dark eyed white (DEW), and the silver. All the other colors of a ferret are variations on one of these four categories.

Waardenburg-like coloring

Ferrets with a white stripe on their face or a fully white head, primarily blazes, badgers, and pandas, almost certainly carry a congenital defect which shares some similarities to Waardenburg syndrome. This causes, among other things, a cranial deformation in the womb which broadens the skull, white face markings, and also partial or total deafness. It is estimated as many as 75 percent of ferrets with these Waardenburg-like colorings are deaf.

White ferrets were favored in the Middle Ages for the ease in seeing them in thick undergrowth. Leonardo da Vinci's painting Lady with an Ermine is likely mislabelled; the animal is probably a ferret, not a stoat, (for which "ermine" is an alternative name for the animal in its white winter coat). Similarly, the ermine portrait of Queen Elizabeth the First shows her with her pet ferret, which has been decorated with painted-on heraldic ermine spots.

"The Ferreter's Tapestry" is a 15th-century tapestry from Burgundy, France, now part of the Burrell Collection housed in the Glasgow Museum and Art Galleries. It shows a group of peasants hunting rabbits with nets and white ferrets. This image was reproduced in Renaissance Dress In Italy 1400–1500, by Jacqueline Herald, Bell & Hyman – ISBN 0-391-02362-4.

Gaston Phoebus' Book Of The Hunt was written in approximately 1389 to explain how to hunt different kinds of animals, including how to use ferrets to hunt rabbits. Illustrations show how multicolored ferrets that were fitted with muzzles were used to chase rabbits out of their warrens and into waiting nets.

Import restrictions

- Australia

Ferrets cannot be imported into Australia. A report drafted in August 2000 seems to be the only effort made to date to change the situation.[63]

- Canada

Ferrets brought from anywhere except the US require a Permit to Import from the Canadian Food Inspection Agency Animal Health Office. Ferrets from the US require only a vaccination certificate signed by a veterinarian. Ferrets under three months old are not subject to any import restrictions.[64]

- European Union

As of July 2004, dogs, cats, and ferrets can travel freely within the European Union under the Pet passport scheme. To cross a border within the EU, ferrets require at minimum an EU PETS passport and an identification microchip (though some countries will accept a tattoo instead). Vaccinations are required; most countries require a rabies vaccine, and some require a distemper vaccine and treatment for ticks and fleas 24 to 48 hours before entry. Ferrets occasionally need to be quarantined before entering the country. PETS travel information is available from any EU veterinarian or on government websites.

- United Kingdom

The UK accepts ferrets under the EU's PETS travel scheme. Ferrets must be microchipped, vaccinated against rabies, and documented. They must be treated for ticks and tapeworms 24 to 48 hours before entry. They must also arrive via an authorized route. Ferrets arriving from outside the EU may be subject to a six-month quarantine.[65]

See also

References

- ↑ Harris & Yalden 2008, pp. 485–487

- ↑ Bradley Hills Animal Hospital, Bethesda, Maryland, USA, on lifespan of Ferrets. Bradleyhills.com. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ "Ferrets: New Zealand animal pests". Department of Conservation. New Zealand Department of Conservation (DOC). 11 August 2006. Archived from the original on 24 July 2014. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ↑ ferret. Merriam-webster.com. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ Thomson, P. D. (1951). "A History of the Ferret". Journal of the History of Medicine and Allied Sciences. vi (Autumn): 471–480. doi:10.1093/jhmas/VI.Autumn.471. (subscription required (help)).

- ↑ "All about ferrets". New Jersey Veterinary Medical Association. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Domestic ferret". Elmwood Park Zoo. Retrieved January 15, 2015.

- ↑ "Ferrets". Pet Health Information. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Robertson, John G. (1991). Robertson's Words for a Modern Age: A Cross Reference of Latin and Greek Combining Elements. Senior Scribe Publications. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-9630919-1-8.

- ↑ Brown, Susan, A. "Inherited behavior traits of the domesticated ferret". weaselwords.com. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ Clapperton, BK; Minot EO; Crump DR (April 1988). "An Olfactory Recognition System in the Ferret Mustela furo L. (Carnivora: Mustelidae)". Animal Behaviour. Academic Press. 36 (2): 541–553. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(88)80025-3.

- ↑ Zhang, JX; Soini HA; Bruce KE; Wiesler D; Woodley SK; Baum MJ; Novotny MV (November 2005). "Putative Chemosignals of the Ferret (Mustela furo) Associated with Individual and Gender Recognition". Chemical Senses. Oxford University Press. 30 (9): 727–737. doi:10.1093/chemse/bji065. PMID 16221798. Online. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ↑ Mitchell, Mark A.; Tully, Thomas N. (2009). Manual of exotic pet practice. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 372. ISBN 978-1-4160-0119-5.

- ↑ Schilling, Kim; Brown, Susan (2011). Ferrets For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 302. ISBN 978-1-118-05154-2.

- ↑ Tynes, Valerie V. (2010). Behavior of Exotic Pets. Chichester, West Sussex: Blackwell Pub. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-8138-0078-3.

- ↑ Williams, Bruce H. (January 1999) Controversy and Confusion in Interpretation of Ferret Clinical Pathology, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology: "... the ferret, being by nature an obligate carnivore, has an extremely short digestive tract, and requires meals as often as every four to six hours."

- ↑ Rethinking The Ferret Diet – Info about species-appropriate diets, and the negative effects of commercially prepared diets, written by a veterinarian. Veterinarypartner.com. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ McLeod, Lianne. Feeding Your Ferret. exoticpets.about.com

- ↑ "Feeding Your Ferret," The Pet Wiki, Retrieved February 26, 2014. Thepetwiki.com. Retrieved 2012-02-28.

- ↑ "Feeding Ferrets whole rabbits ?". The Hunting Life. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Raw Diets". For Ferrets Only. Retrieved 6 October 2012.

- ↑ "Gastrointestinal Disease in the Ferret". Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ "Frequently Asked Questions". American Ferret Association. Retrieved 24 April 2014.

- ↑ Van Dahm, Mary. "An Owners Guide to Ferret Health Care". WeaselWords.com. Retrieved 1 September 2013.

- ↑ Sato, JJ; Hosoda, T; Wolsan, M; Tsuchiya, K; Yamamoto, M; Suzuki, H (February 2003). "Phylogenetic relationships and divergence times among mustelids (Mammalia: Carnivora) based on nucleotide sequences of the nuclear interphotoreceptor retinoid binding protein and mitochondrial cytochrome b genes". Zoological Science. 20 (2): 243–64. doi:10.2108/zsj.20.243. PMID 12655187.

- ↑ Glover, James. "The Ancestry Of The Domestic Ferret". PetPeoplesPlace.com. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Church, Bob. "Ferret FAQ — Natural History". ferretcentral.org. Retrieved 2007-08-25.

- ↑ Matulich, Erika, Ph.D. (2000). "Ferret Domesticity: A Primer.". Ferrets USA. Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Brown, Susan, DVM. "History of the Ferret". Retrieved 2008-03-05.

- ↑ "Feral Ferrets in New Zealand". California's Plants and Animals. California Department of Fish and Game. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ "Rabbit control". A Hundred Years of Rabbit Impacts, and Future Control Options. New Zealand Ministry of Agriculture and Forestry (MAF) Rabbit Biocontrol Advisory Group. Archived from the original on June 17, 2001. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ Plinius the Elder, Natural History, 8 lxxxi 218 (in Latin)

- ↑ Pliny the Elder (1601). "LV. Of Hares and Connies.". Natural History, Book VIII. Philemon Holland (trans). Retrieved 19 April 2011.

- ↑ Mackay, Thomas, ed. (1891). Plea for Liberty. D. Appleton and Co. Retrieved 2007-06-26.

- ↑ "In Mystery, Ferret Thefts Sweep Southern England". The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ Jurek, R.M. (1998). A review of national and California population estimates of pet ferrets. Calif. Dep. Fish and Game, Wildl. Manage. Div., Bird and Mammal Conservation Program Rep. 98-09. Sacramento, CA.

- ↑ "Ferret Housing : The Humane Society of the United States". www.humanesociety.org. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ↑ Wildlife Act 1953 – Schedule 8

- ↑ "Fish and Game Code Section 2118". California Codes. State of California. Retrieved 2006-09-19. the Code states, in part: "animals of the families Viverridae and Mustelidae in the order Carnivora are restricted because such animals are undesirable and a menace to native wildlife, the agricultural interests of the state, or to the public health or safety."

- ↑ "Section 671(c)(2)(K)(5): "Family Mustelidae"". California Code Of Regulations, Title 14: Natural Resources, Division 1: "Fish And Game Commission — Department Of Fish And Game", Subdivision 3: "General Regulations", Chapter 3: "Miscellaneous", Section 671: "Importation, Transportation and Possession of Live Restricted Animals". Retrieved 2006-09-19. Ferrets are not among the exceptions to the classification "Those species listed because they pose a threat to native wildlife, the agriculture interests of the state or to public health or safety are termed 'detrimental animals'" and are designated by the letter "D".

- ↑ "News Release:Illegal Ferret Found in Kailua". State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- 1 2 3 Katie Redshoes. "Are Ferrets Legal in ...?". List of Ferret-Free Zones. Retrieved 2007-08-26.

- ↑ "New York's Health Board Dashes the Hopes of Ferret Fans". NYTimes.com. NY Times. Retrieved 11 March 2015.

- ↑ Michael M. Grynbaum. "De Blasio's Latest Break With His Predecessors: Ending a Ban on Ferrets". Retrieved 2014-05-27.

- ↑ "R.I. Ferret Regulations" (PDF). State of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations Department of Environmental Management. June 27, 1997. Retrieved 2007-07-05.

- ↑ "Wild Bird and Game Bird Breeder Permit Application" (PDF). Illinois Department of Natural Resources. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-08-05. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ "Wild Animals/Exotica". Georgia Department of Natural Resources. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

The exotic species listed below, except where otherwise noted, may not be held as pets in Georgia. [...] Carnivores (weasels, ferrets, foxes, cats, bears, wolves, etc.); all species. Note: European ferrets are legal as pets if neutered by 7 months old and vaccinated against rabies.

- ↑ "Dallas". Prohibited by Ordinance. Ferret Lover's Club of Texas. 1996–2005. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ "Animal Services". Dallas City Code, Chapter 7: "Animals"; Article VII: "Miscellaneous". American Legal Publishing Corporation. Retrieved 2006-09-19.

- ↑ "Companion Animals". Wisconsin Department of Agriculture, Trade, and Consumer Protection. Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ↑ Gallick v. Barto, 828 F.Supp. 1168 (M.D.Pa. 1993).

- ↑ "Hokkaido Animal Welfare and Control Ordinance". Hokkaido Animal Welfare and Control Ordinance Chapter 2, Section 3. Archived from the original on March 9, 2008. Retrieved 2009-04-10.

- ↑ Matsuoka, Y.; Lamirande, E. W.; Subbarao, K. (2009). "The Ferret Model for Influenza". Current Protocols in Microbiology. doi:10.1002/9780471729259.mc15g02s13. ISBN 0471729256.

- ↑ Maher JA, DeStefano J (2004). "The ferret: an animal model to study influenza virus". Lab Anim (NY). 33 (9): 50–53. doi:10.1038/laban1004-50. PMID 15457202.

- ↑ Van Den Brand, J. M. A.; Stittelaar, K. J.; Van Amerongen, G.; Rimmelzwaan, G. F.; Simon, J.; De Wit, E.; Munster, V.; Bestebroer, T.; Fouchier, R. A. M.; Kuiken, T.; Osterhaus, A. D. M. E. (2010). "Severity of Pneumonia Due to New H1N1 Influenza Virus in Ferrets is Intermediate between That Due to Seasonal H1N1 Virus and Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza H5N1 Virus". The Journal of Infectious Diseases. 201 (7): 993. doi:10.1086/651132. PMID 20187747.

- ↑ Abanses, J. C.; Arima, S; Rubin, B. K. (2009). "Vicks Vapo Rub induces mucin secretion, decreases ciliary beat frequency, and increases tracheal mucus transport in the ferret trachea". CHEST Journal. 135 (1): 143–8. doi:10.1378/chest.08-0095. PMID 19136404.

- ↑ Crawford, Richard L. and Adams, Kristina M. (2006) "Information Resources on the Care and Welfare of Ferrets", USDA Animal Welfare Information Center.

- ↑ "Ferret Racing | Countryman Fairs". www.countrymanfairs.co.uk. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ↑ "Ferret Racing - Starescue - STA Ferret Rescue". www.starescue.org.uk. Retrieved 2015-04-19.

- ↑ Schilling, Kim; Brown, Susan (2011). Ferrets For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 125–. ISBN 978-1-118-05154-2.

- ↑ Borgmann, Dmitri A. (1967). Beyond Language: Adventures in Word and Thought. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons. pp. 79–80, 146, 251–254. OCLC 655067975.

- ↑ "American Ferret Association: Ferret Color and Pattern Standards". Ferret.org. Retrieved 2008-11-30.

- ↑ "Importation of Ferrets into Australia, Import Risk Analysis — Draft Report" (PDF). Australian Quarantine and Inspection Service (AQIS). August 2000. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-10. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ "Importation of Foxes, Skunks, Raccoons and Ferrets". Pet Imports. Canadian Food Inspection Agency. 2006-03-20. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

- ↑ "PETS: How to bring your ferret into or back into the UK under the Pet Travel Scheme (PETS)". Animal health & welfare. Department of Environment Food and Rural Affairs (defra) © Crown copyright 2006. Retrieved 2006-09-12.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Mustela putorius. |

| Wikispecies has information related to: Mustela putorius furo |

-

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ferret". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ferret". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. - Isaacsen, Adolph (1886) All about ferrets and rats

- View the ferret genome on Ensembl

- View the musFur1 genome assembly in the UCSC Genome Browser.