Dog

| Domestic dog Temporal range: 0.033–0 Ma | |

|---|---|

| |

| Selection of the different breeds of dog. | |

| Domesticated | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Carnivora |

| Suborder: | Caniformia |

| Family: | Canidae |

| Genus: | Canis |

| Species: | C. lupus |

| Subspecies: | C. l. familiaris[1] |

| Trinomial name | |

| Canis lupus familiaris[1] | |

The domestic dog (Canis lupus familiaris or Canis familiaris)[2] is a member of genus Canis (canines) that forms part of the wolf-like canids,[3] and is the most widely abundant carnivore.[4][5][6] The dog and the extant gray wolf are sister taxa,[7][8][9] with modern wolves not closely related to the wolves that were first domesticated.[8][9] The dog was the first domesticated species[9][10] and has been selectively bred over millennia for various behaviors, sensory capabilities, and physical attributes.[11]

Their long association with humans has led dogs to be uniquely attuned to human behavior[12] and they are able to thrive on a starch-rich diet that would be inadequate for other canid species.[13] Dogs vary widely in shape, size and colours.[14] Dogs perform many roles for people, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and military, companionship and, more recently, aiding handicapped individuals. This influence on human society has given them the sobriquet, "man's best friend".

Etymology

The term "domestic dog" is generally used for both domesticated and feral varieties. The English word dog comes from Middle English dogge, from Old English docga, a "powerful dog breed".[15] The term may possibly derive from Proto-Germanic *dukkōn, represented in Old English finger-docce ("finger-muscle").[16] The word also shows the familiar petname diminutive -ga also seen in frogga "frog", picga "pig", stagga "stag", wicga "beetle, worm", among others.[17] The term dog may ultimately derive from the earliest layer of Proto-Indo-European vocabulary.[18]

In 14th-century England, hound (from Old English: hund) was the general word for all domestic canines, and dog referred to a subtype of hound, a group including the mastiff. It is believed this "dog" type was so common, it eventually became the prototype of the category "hound".[19] By the 16th century, dog had become the general word, and hound had begun to refer only to types used for hunting.[20] The word "hound" is ultimately derived from the Proto-Indo-European word *kwon-, "dog".[21] This semantic shift may be compared to in German, where the corresponding words Dogge and Hund kept their original meanings.

A male canine is referred to as a dog, while a female is called a bitch. The father of a litter is called the sire, and the mother is called the dam. (Middle English bicche, from Old English bicce, ultimately from Old Norse bikkja) The process of birth is whelping, from the Old English word hwelp; the modern English word "whelp" is an alternate term for puppy.[22] A litter refers to the multiple offspring at one birth which are called puppies or pups from the French poupée, "doll", which has mostly replaced the older term "whelp".[23]

Taxonomy

The dog is classified as Canis lupus familiaris under the Biological Species Concept and Canis familiaris under the Evolutionary Species Concept.[2]:p1

In 1758, the taxonomist Linnaeus published in Systema Naturae a categorization of species which included the Canis species. Canis is a Latin word meaning dog,[24] and the list included the dog-like carnivores: the domestic dog, wolves, foxes and jackals. The dog was classified as Canis familiaris,[25] which means "Dog-family"[26] or the family dog. On the next page he recorded the wolf as Canis lupus, which means "Dog-wolf".[27] In 1978, a review aimed at reducing the number of recognized Canis species proposed that "Canis dingo is now generally regarded as a distinctive feral domestic dog. Canis familiaris is used for domestic dogs, although taxonomically it should probably be synonymous with Canis lupus."[28] In 1982, the first edition of Mammal Species of the World listed Canis familiaris under Canis lupus with the comment: "Probably ancestor of and conspecific with the domestic dog, familiaris. Canis familiaris has page priority over Canis lupus, but both were published simultaneously in Linnaeus (1758), and Canis lupus has been universally used for this species",[29] which avoided classifying the wolf as the family dog. The dog is now listed among the many other Latin-named subspecies of Canis lupus as Canis lupus familiaris.[1]

In 2003, the ICZN ruled in its Opinion 2027 that if wild animals and their domesticated derivatives are regarded as one species, then the scientific name of that species is the scientific name of the wild animal. In 2005, the third edition of Mammal Species of the World upheld Opinion 2027 with the name Lupus and the note: "Includes the domestic dog as a subspecies, with the dingo provisionally separate - artificial variants created by domestication and selective breeding".[1][30] However, Canis familiaris is sometimes used due to an ongoing nomenclature debate because wild and domestic animals are separately recognizable entities and that the ICZN allowed users a choice as to which name they could use,[31] and a number of internationally recognized researchers prefer to use Canis familiaris.[32]

Origin

The origin of the domestic dog is not clear. The domestic dog is a member of genus Canis (canines) that forms part of the wolf-like canids,[3] and is the most widely abundant carnivore.[4][5][6] The closest living relative of the dog is the gray wolf and there is no evidence of any other canine contributing to its genetic lineage.[4][5][33][7] The dog and the extant gray wolf form two sister clades,[7][8][9] with modern wolves not closely related to the wolves that were first domesticated.[8][9] The archaeological record shows the first undisputed dog remains buried beside humans 14,700 years ago,[34] with disputed remains occurring 36,000 years ago.[35] These dates imply that the earliest dogs arose in the time of human hunter-gatherers and not agriculturists.[5][8] The dog was the first domesticated species.[9][10]

Where the genetic divergence of dog and wolf took place remains controversial, with the most plausible proposals spanning Western Europe,[36][5] Central Asia,[36][37] and East Asia.[36][38] This has been made more complicated by the most recent proposal that fits the available evidence, which is that an initial wolf population split into East and West Eurasian wolves, these were then domesticated independently before going extinct into two distinct dog populations between 14,000-6,400 years ago, and then the Western Eurasian dog population was partially and gradually replaced by East Asian dogs that were brought by humans at least 6,400 years ago.[36][39][40]

Terminology

- The term dog typically is applied both to the species (or subspecies) as a whole, and any adult male member of the same.

- An adult female is a bitch. In some countries, especially in North America, dog is used instead due to the vulgar connotation of bitch.

- An adult male capable of reproduction is a stud.

- An adult female capable of reproduction is a brood bitch, or brood mother.

- Immature males or females (that is, animals that are incapable of reproduction) are pups or puppies.

- A group of pups from the same gestation period is a litter.

- The father of a litter is a sire. It is possible for one litter to have multiple sires.

- The mother of a litter is a dam.

- A group of any three or more adults is a pack.

Biology

Anatomy

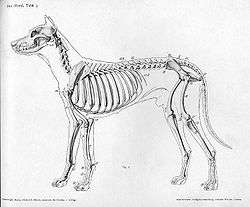

Domestic dogs have been selectively bred for millennia for various behaviors, sensory capabilities, and physical attributes.[11] Modern dog breeds show more variation in size, appearance, and behavior than any other domestic animal.[11] Dogs are predators and scavengers, and like many other predatory mammals, the dog has powerful muscles, fused wrist bones, a cardiovascular system that supports both sprinting and endurance, and teeth for catching and tearing.

Size and weight

Dogs are highly variable in height and weight. The smallest known adult dog was a Yorkshire Terrier, that stood only 6.3 cm (2.5 in) at the shoulder, 9.5 cm (3.7 in) in length along the head-and-body, and weighed only 113 grams (4.0 oz). The largest known dog was an English Mastiff which weighed 155.6 kg (343 lb) and was 250 cm (98 in) from the snout to the tail.[41] The tallest dog is a Great Dane that stands 106.7 cm (42.0 in) at the shoulder.[42]

Senses

The dog's senses include vision, hearing, sense of smell, sense of taste, touch and sensitivity to the earth's magnetic field. Another study suggested that dogs can see the earth's magnetic field.[43][44]

- See further: Dog anatomy-senses

Coat

The coats of domestic dogs are of two varieties: "double" being common with dogs (as well as wolves) originating from colder climates, made up of a coarse guard hair and a soft down hair, or "single", with the topcoat only.

Domestic dogs often display the remnants of countershading, a common natural camouflage pattern. A countershaded animal will have dark coloring on its upper surfaces and light coloring below,[45] which reduces its general visibility. Thus, many breeds will have an occasional "blaze", stripe, or "star" of white fur on their chest or underside.[46]

Tail

There are many different shapes for dog tails: straight, straight up, sickle, curled, or cork-screw. As with many canids, one of the primary functions of a dog's tail is to communicate their emotional state, which can be important in getting along with others. In some hunting dogs, however, the tail is traditionally docked to avoid injuries.[47] In some breeds, such as the Braque du Bourbonnais, puppies can be born with a short tail or no tail at all.[48]

Health

There are many household plants that are poisonous to dogs including begonia, Poinsettia and aloe vera.[49]

Some breeds of dogs are prone to certain genetic ailments such as elbow and hip dysplasia, blindness, deafness, pulmonic stenosis, cleft palate, and trick knees. Two serious medical conditions particularly affecting dogs are pyometra, affecting unspayed females of all types and ages, and bloat, which affects the larger breeds or deep-chested dogs. Both of these are acute conditions, and can kill rapidly. Dogs are also susceptible to parasites such as fleas, ticks, and mites, as well as hookworms, tapeworms, roundworms, and heartworms.

A number of common human foods and household ingestibles are toxic to dogs, including chocolate solids (theobromine poisoning), onion and garlic (thiosulphate, sulfoxide or disulfide poisoning),[50] grapes and raisins, macadamia nuts, xylitol,[51] as well as various plants and other potentially ingested materials.[52][53] The nicotine in tobacco can also be dangerous. Dogs can be exposed to the substance by scavenging garbage or ashtrays; eating cigars and cigarettes. Signs can be vomiting of large amounts (e.g., from eating cigar butts) or diarrhea. Some other signs are abdominal pain, loss of coordination, collapse, or death.[54] Dogs are highly susceptible to theobromine poisoning, typically from ingestion of chocolate. Theobromine is toxic to dogs because, although the dog's metabolism is capable of breaking down the chemical, the process is so slow that even small amounts of chocolate can be fatal, especially dark chocolate.

Dogs are also vulnerable to some of the same health conditions as humans, including diabetes, dental and heart disease, epilepsy, cancer, hypothyroidism, and arthritis.[55]

Lifespan

In 2013, a study found that mixed breeds live on average 1.2 years longer than pure breeds, and that increasing body-weight was negatively correlated with longevity (i.e. the heavier the dog the shorter its lifespan).[56]

The typical lifespan of dogs varies widely among breeds, but for most the median longevity, the age at which half the dogs in a population have died and half are still alive, ranges from 10 to 13 years.[57][58][59][60] Individual dogs may live well beyond the median of their breed.

The breed with the shortest lifespan (among breeds for which there is a questionnaire survey with a reasonable sample size) is the Dogue de Bordeaux, with a median longevity of about 5.2 years, but several breeds, including Miniature Bull Terriers, Bloodhounds, and Irish Wolfhounds are nearly as short-lived, with median longevities of 6 to 7 years.[60]

The longest-lived breeds, including Toy Poodles, Japanese Spitz, Border Terriers, and Tibetan Spaniels, have median longevities of 14 to 15 years.[60] The median longevity of mixed-breed dogs, taken as an average of all sizes, is one or more years longer than that of purebred dogs when all breeds are averaged.[58][59][60][61] The dog widely reported to be the longest-lived is "Bluey", who died in 1939 and was claimed to be 29.5 years old at the time of his death. On 5 December 2011, Pusuke, the world's oldest living dog recognized by Guinness Book of World Records, died aged 26 years and 9 months.[62]

Reproduction

In domestic dogs, sexual maturity begins to happen around age six to twelve months for both males and females,[11][63] although this can be delayed until up to two years old for some large breeds. This is the time at which female dogs will have their first estrous cycle. They will experience subsequent estrous cycles semiannually, during which the body prepares for pregnancy. At the peak of the cycle, females will come into estrus, being mentally and physically receptive to copulation.[11] Because the ova survive and are capable of being fertilized for a week after ovulation, it is possible for a female to mate with more than one male.[11]

2–5 days after conception fertilization occurs, 14–16 days later the embryo attaches to the uterus and after 22–23 days the heart beat is detectable.[64][65]

Dogs bear their litters roughly 58 to 68 days after fertilization,[11][66] with an average of 63 days, although the length of gestation can vary. An average litter consists of about six puppies,[67] though this number may vary widely based on the breed of dog. In general, toy dogs produce from one to four puppies in each litter, while much larger breeds may average as many as twelve.

Some dog breeds have acquired traits through selective breeding that interfere with reproduction. Male French Bulldogs, for instance, are incapable of mounting the female. For many dogs of this breed, the female must be artificially inseminated in order to reproduce.[68]

Neutering

Neutering refers to the sterilization of animals, usually by removal of the male's testicles or the female's ovaries and uterus, in order to eliminate the ability to procreate and reduce sex drive. Because of the overpopulation of dogs in some countries, many animal control agencies, such as the American Society for the Prevention of Cruelty to Animals (ASPCA), advise that dogs not intended for further breeding should be neutered, so that they do not have undesired puppies that may have to later be euthanized.[69]

According to the Humane Society of the United States, 3–4 million dogs and cats are put down each year in the United States and many more are confined to cages in shelters because there are many more animals than there are homes. Spaying or castrating dogs helps keep overpopulation down.[70] Local humane societies, SPCAs, and other animal protection organizations urge people to neuter their pets and to adopt animals from shelters instead of purchasing them.

Neutering reduces problems caused by hypersexuality, especially in male dogs.[71] Spayed female dogs are less likely to develop some forms of cancer, affecting mammary glands, ovaries, and other reproductive organs.[72] However, neutering increases the risk of urinary incontinence in female dogs,[73] and prostate cancer in males,[74] as well as osteosarcoma, hemangiosarcoma, cruciate ligament rupture, obesity, and diabetes mellitus in either sex.[75]

Inbreeding depression

A common breeding practice for pet dogs is mating between close relatives (e.g. between half- and full siblings).[76] In a study of seven different French breeds of dogs (Bernese mountain dog, basset hound, Cairn terrier, Epagneul Breton, German Shepard dog, Leonberger, and West Highland white terrier) it was found that inbreeding decreases litter size and survival.[77] Another analysis of data on 42,855 dachshund litters, found that as the inbreeding coefficient increased, litter size decreased and the percentage of stillborn puppies increased, thus indicating inbreeding depression.[78]

About 22% of boxer puppies die before reaching 7 weeks of age.[79] Stillbirth is the most frequent cause of death, followed by infection. Mortality due to infection was found to increase significantly with increases in inbreeding.[79] Inbreeding depression is considered to be due largely to the expression of homozygous deleterious recessive mutations.[80] Outcrossing between unrelated individuals, including dogs of different breeds, results in the beneficial masking of deleterious recessive mutations in progeny.[81]

Intelligence, behavior and communication

Intelligence

Dog intelligence is the ability of the dog to perceive information and retain it as knowledge for applying to solve problems. Dogs have been shown to learn by inference. A study with Rico showed that he knew the labels of over 200 different items. He inferred the names of novel items by exclusion learning and correctly retrieved those novel items immediately and also 4 weeks after the initial exposure. Dogs have advanced memory skills. A study documented the learning and memory capabilities of a border collie, "Chaser", who had learned the names and could associate by verbal command over 1,000 words. Dogs are able to read and react appropriately to human body language such as gesturing and pointing, and to understand human voice commands. Dogs demonstrate a theory of mind by engaging in deception. An experimental study showed compelling evidence that Australian dingos can outperform domestic dogs in non-social problem-solving, indicating that domestic dogs may have lost much of their original problem-solving abilities once they joined humans.[82] Another study indicated that after undergoing training to solve a simple manipulation task, dogs that are faced with an insoluble version of the same problem look at the human, while socialized wolves do not.[83] Modern domestic dogs use humans to solve their problems for them.[84][85]

Behavior

Dog behavior is the internally coordinated responses (actions or inactions) of the domestic dog (individuals or groups) to internal and/or external stimuli.[86] As the oldest domesticated species, with estimates ranging from 9,000–30,000 years BCE, the minds of dogs inevitably have been shaped by millennia of contact with humans. As a result of this physical and social evolution, dogs, more than any other species, have acquired the ability to understand and communicate with humans and they are uniquely attuned to our behaviors.[12] Behavioral scientists have uncovered a surprising set of social-cognitive abilities in the otherwise humble domestic dog. These abilities are not possessed by the dog's closest canine relatives nor by other highly intelligent mammals such as great apes. Rather, these skills parallel some of the social-cognitive skills of human children.[87]

Communication

Dog communication is about how dogs "speak" to each other, how they understand messages that humans send to them, and how humans can translate the ideas that dogs are trying to transmit.[88]:xii These communication behaviors include eye gaze, facial expression, vocalization, body posture (including movements of bodies and limbs) and gustatory communication (scents, pheromones and taste). Humans communicate with dogs by using vocalization, hand signals and body posture.

Compared to wolves

Physical characteristics

Despite their close genetic relationship and the ability to inter-breed, there are a number of diagnostic features to distinguish the gray wolves from domestic dogs. Domesticated dogs are clearly distinguishable from wolves by starch gel electrophoresis of red blood cell acid phosphatase.[90] The tympanic bullae are large, convex and almost spherical in gray wolves, while the bullae of dogs are smaller, compressed and slightly crumpled.[91] Compared to equally sized wolves, dogs tend to have 20% smaller skulls and 30% smaller brains.[92]:35 The teeth of gray wolves are also proportionately larger than those of dogs.[93] Compared to wolves, dogs have a more domed forehead. The temporalis muscle that closes the jaws is more robust in wolves.[2]:p158 Wolves do not have dewclaws on their back legs, unless there has been admixture with dogs that had them.[94] Dogs lack a functioning pre-caudal gland, and most enter estrus twice yearly, unlike gray wolves which only do so once a year.[95] Dogs require fewer calories to function than wolves. The dog's limp ears may be the result of atrophy of the jaw muscles.[96] The skin of domestic dogs tends to be thicker than that of wolves, with some Inuit tribes favoring the former for use as clothing due to its greater resistance to wear and tear in harsh weather.[96] The paws of a dog are half the size of those of a wolf, and their tails tend to curl upwards, another trait not found in wolves[97] The dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds, and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[98] For example, height measured to the withers ranges from a 6 inches (150 mm) in the Chihuahua to 3.3 feet (1.0 m) in the Irish Wolfhound; color varies from white through grays (usually called "blue") to black, and browns from light (tan) to dark ("red" or "chocolate") in a wide variation of patterns; coats can be short or long, coarse-haired to wool-like, straight, curly, or smooth.[99] It is common for most breeds to shed their coat.

Behavioral differences

Unlike other domestic species which were primarily selected for production-related traits, dogs were initially selected for their behaviors.[100][101] In 2016, a study found that there were only 11 fixed genes that showed variation between wolves and dogs. These gene variations were unlikely to have been the result of natural evolution, and indicate selection on both morphology and behavior during dog domestication. These genes have been shown to affect the catecholamine synthesis pathway, with the majority of the genes affecting the fight-or-flight response[101][102] (i.e. selection for tameness), and emotional processing.[101] Dogs generally show reduced fear and aggression compared to wolves.[101][103] Some of these genes have been associated with aggression in some dog breeds, indicating their importance in both the initial domestication and then later in breed formation.[101]

Ecology

Population and habitat

The global dog population is estimated at 900 million and rising.[104][105] Although it is said that the "dog is man's best friend"[106] regarding 17–24% of dogs in developed countries, in the developing world they are feral, village or community dogs, with pet dogs uncommon.[96] These live their lives as scavengers and have never been owned by humans, with one study showing their most common response when approached by strangers was to run away (52%) or respond with aggression (11%).[107] We know little about these dogs, nor about the dogs that live in developed countries that are feral, stray or are in shelters, yet the great majority of modern research on dog cognition has focused on pet dogs living in human homes.[108]

Competitors

Being the most abundant carnivore, feral and free-ranging dogs have the greatest potential to compete with wolves. A review of the studies in the competitive effects of dogs on sympatric carnivores did not mention any research on competition between dogs and wolves.[105][109] Competition would favor the wolf that is known to kill dogs, however wolves tend to live in pairs or in small packs in areas where they are highly persecuted, giving them a disadvantage facing large dog groups.[105][110]

Wolves kill dogs wherever the two canids occur.[111] One survey claims that in Wisconsin in 1999 more compensation had been paid for dog losses than livestock, however in Wisconsin wolves will often kill hunting dogs, perhaps because they are in the wolf's territory.[111] Some wolf pairs have been reported to prey on dogs by having one wolf lure the dog out into heavy brush where the second animal waits in ambush.[112] In some instances, wolves have displayed an uncharacteristic fearlessness of humans and buildings when attacking dogs, to the extent that they have to be beaten off or killed.[113] Although the numbers of dogs killed each year are relatively low, it induces a fear of wolves entering villages and farmyards to take dogs. In many cultures, there are strong social and emotional bonds between humans and their dogs that can be seen as family members or working team members. The loss of a dog can lead to strong emotional responses with demands for more liberal wolf hunting regulations.[105]

Coyotes and big cats have also been known to attack dogs. Leopards in particular are known to have a predilection for dogs, and have been recorded to kill and consume them regardless of the dog's size or ferocity.[114] Tigers in Manchuria, Indochina, Indonesia, and Malaysia are reputed to kill dogs with the same vigor as leopards.[115] Striped hyenas are major predators of village dogs in Turkmenistan, India, and the Caucasus.[116]

Diet

Despite their descent from wolves and classification as Carnivora, dogs are variously described in scholarly and other writings as carnivores[117][118] or omnivores.[11][119][120][121] Unlike obligate carnivores, dogs can adapt to a wide-ranging diet, and are not dependent on meat-specific protein nor a very high level of protein in order to fulfill their basic dietary requirements. Dogs will healthily digest a variety of foods, including vegetables and grains, and can consume a large proportion of these in their diet, however all-meat diets are not recommended for dogs due to their lack of calcium and iron.[11] Comparing dogs and wolves, dogs have adaptations in genes involved in starch digestion that contribute to an increased ability to thrive on a starch-rich diet.[13]

Breeds

Most breeds of dog are at most a few hundred years old, having been artificially selected for particular morphologies and behaviors by people for specific functional roles. Through this selective breeding, the dog has developed into hundreds of varied breeds, and shows more behavioral and morphological variation than any other land mammal.[98] For example, height measured to the withers ranges from 15.2 centimetres (6.0 in) in the Chihuahua to about 76 cm (30 in) in the Irish Wolfhound; color varies from white through grays (usually called "blue") to black, and browns from light (tan) to dark ("red" or "chocolate") in a wide variation of patterns; coats can be short or long, coarse-haired to wool-like, straight, curly, or smooth.[99] It is common for most breeds to shed this coat.

While all dogs are genetically very similar,[122] natural selection and selective breeding have reinforced certain characteristics in certain populations of dogs, giving rise to dog types and dog breeds. Dog types are broad categories based on function, genetics, or characteristics.[123] Dog breeds are groups of animals that possess a set of inherited characteristics that distinguishes them from other animals within the same species. Modern dog breeds are non-scientific classifications of dogs kept by modern kennel clubs.

Purebred dogs of one breed are genetically distinguishable from purebred dogs of other breeds,[124] but the means by which kennel clubs classify dogs is unsystematic. DNA microsatellite analyses of 85 dog breeds showed they fell into four major types of dogs that were statistically distinct.[124] These include the "old world dogs" (e.g., Malamute and Shar Pei), "Mastiff"-type (e.g., English Mastiff), "herding"-type (e.g., Border Collie), and "all others" (also called "modern"- or "hunting"-type).[124][125]

Roles with humans

Domestic dogs inherited complex behaviors, such as bite inhibition, from their wolf ancestors, which would have been pack hunters with complex body language. These sophisticated forms of social cognition and communication may account for their trainability, playfulness, and ability to fit into human households and social situations, and these attributes have given dogs a relationship with humans that has enabled them to become one of the most successful species on the planet today.[126]:pages95-136

The dogs' value to early human hunter-gatherers led to them quickly becoming ubiquitous across world cultures. Dogs perform many roles for people, such as hunting, herding, pulling loads, protection, assisting police and military, companionship, and, more recently, aiding handicapped individuals. This influence on human society has given them the nickname "man's best friend" in the Western world. In some cultures, however, dogs are also a source of meat.[127][128]

Early roles

Wolves, and their dog descendants, would have derived significant benefits from living in human camps—more safety, more reliable food, lesser caloric needs, and more chance to breed.[129] They would have benefited from humans' upright gait that gives them larger range over which to see potential predators and prey, as well as color vision that, at least by day, gives humans better visual discrimination.[129] Camp dogs would also have benefited from human tool use, as in bringing down larger prey and controlling fire for a range of purposes.[129]

The dogs of Thibet are twice the size of those seen in India, with large heads and hairy bodies. They are powerful animals, and are said to be able to kill a tiger. During the day they are kept chained up, and are let loose at night to guard their masters' house.[130]

Humans would also have derived enormous benefit from the dogs associated with their camps.[131] For instance, dogs would have improved sanitation by cleaning up food scraps.[131] Dogs may have provided warmth, as referred to in the Australian Aboriginal expression "three dog night" (an exceptionally cold night), and they would have alerted the camp to the presence of predators or strangers, using their acute hearing to provide an early warning.[131]

Anthropologists believe the most significant benefit would have been the use of dogs' robust sense of smell to assist with the hunt.[131] The relationship between the presence of a dog and success in the hunt is often mentioned as a primary reason for the domestication of the wolf, and a 2004 study of hunter groups with and without a dog gives quantitative support to the hypothesis that the benefits of cooperative hunting was an important factor in wolf domestication.[132]

The cohabitation of dogs and humans would have greatly improved the chances of survival for early human groups, and the domestication of dogs may have been one of the key forces that led to human success.[133]

Emigrants from Siberia that walked across the Bering land bridge into North America may have had dogs in their company, and one writer[134] suggests that the use of sled dogs may have been critical to the success of the waves that entered North America roughly 12,000 years ago,[134] although the earliest archaeological evidence of dog-like canids in North America dates from about 9,400 years ago.[126]:104[135] Dogs were an important part of life for the Athabascan population in North America, and were their only domesticated animal. Dogs also carried much of the load in the migration of the Apache and Navajo tribes 1,400 years ago. Use of dogs as pack animals in these cultures often persisted after the introduction of the horse to North America.[136]

As pets

It is estimated that three-quarters of the world's dog population lives in the developing world as feral, village, or community dogs, with pet dogs uncommon.[96]

"The most widespread form of interspecies bonding occurs between humans and dogs"[131] and the keeping of dogs as companions, particularly by elites, has a long history.[137] (As a possible example, at the Natufian culture site of Ain Mallaha in Israel, dated to 12,000 BC, the remains of an elderly human and a four-to-five-month-old puppy were found buried together).[138] However, pet dog populations grew significantly after World War II as suburbanization increased.[137] In the 1950s and 1960s, dogs were kept outside more often than they tend to be today[139] (using the expression "in the doghouse" to describe exclusion from the group signifies the distance between the doghouse and the home) and were still primarily functional, acting as a guard, children's playmate, or walking companion. From the 1980s, there have been changes in the role of the pet dog, such as the increased role of dogs in the emotional support of their human guardians.[140] People and dogs have become increasingly integrated and implicated in each other's lives,[141] to the point where pet dogs actively shape the way a family and home are experienced.[142]

There have been two major trends in the changing status of pet dogs. The first has been the 'commodification' of the dog, shaping it to conform to human expectations of personality and behaviour.[142] The second has been the broadening of the concept of the family and the home to include dogs-as-dogs within everyday routines and practices.[142]

There are a vast range of commodity forms available to transform a pet dog into an ideal companion.[143] The list of goods, services and places available is enormous: from dog perfumes, couture, furniture and housing, to dog groomers, therapists, trainers and caretakers, dog cafes, spas, parks and beaches, and dog hotels, airlines and cemeteries.[143] While dog training as an organized activity can be traced back to the 18th century, in the last decades of the 20th century it became a high-profile issue as many normal dog behaviors such as barking, jumping up, digging, rolling in dung, fighting, and urine marking (which dogs do to establish territory through scent), became increasingly incompatible with the new role of a pet dog.[144] Dog training books, classes and television programs proliferated as the process of commodifying the pet dog continued.[145]

The majority of contemporary people with dogs describe their pet as part of the family,[142] although some ambivalence about the relationship is evident in the popular reconceptualization of the dog–human family as a pack.[142] A dominance model of dog–human relationships has been promoted by some dog trainers, such as on the television program Dog Whisperer. However it has been disputed that "trying to achieve status" is characteristic of dog–human interactions.[146] Pet dogs play an active role in family life; for example, a study of conversations in dog–human families showed how family members use the dog as a resource, talking to the dog, or talking through the dog, to mediate their interactions with each other.[147]

Increasingly, human family members are engaging in activities centered on the perceived needs and interests of the dog, or in which the dog is an integral partner, such as dog dancing and dog yoga.[143]

According to statistics published by the American Pet Products Manufacturers Association in the National Pet Owner Survey in 2009–2010, it is estimated there are 77.5 million people with pet dogs in the United States.[148] The same survey shows nearly 40% of American households own at least one dog, of which 67% own just one dog, 25% two dogs and nearly 9% more than two dogs. There does not seem to be any gender preference among dogs as pets, as the statistical data reveal an equal number of female and male dog pets. Yet, although several programs are ongoing to promote pet adoption, less than a fifth of the owned dogs come from a shelter.

The latest study using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) comparing humans and dogs showed that dogs have same response to voices and use the same parts of the brain as humans do. This gives dogs the ability to recognize emotional human sounds, making them friendly social pets to humans.[149]

Work

Dogs have lived and worked with humans in so many roles that they have earned the unique nickname, "man's best friend",[150] a phrase used in other languages as well. They have been bred for herding livestock,[151] hunting (e.g. pointers and hounds),[92] rodent control,[11] guarding, helping fishermen with nets, detection dogs, and pulling loads, in addition to their roles as companions.[11] In 1957, a husky-terrier mix named Laika became the first animal to orbit the Earth.[152][153]

Service dogs such as guide dogs, utility dogs, assistance dogs, hearing dogs, and psychological therapy dogs provide assistance to individuals with physical or mental disabilities.[154][155] Some dogs owned by epileptics have been shown to alert their handler when the handler shows signs of an impending seizure, sometimes well in advance of onset, allowing the guardian to seek safety, medication, or medical care.[156]

Dogs included in human activities in terms of helping out humans are usually called working dogs.

Sports and shows

People often enter their dogs in competitions[157] such as breed-conformation shows or sports, including racing, sledding and agility competitions.

In conformation shows, also referred to as breed shows, a judge familiar with the specific dog breed evaluates individual purebred dogs for conformity with their established breed type as described in the breed standard. As the breed standard only deals with the externally observable qualities of the dog (such as appearance, movement, and temperament), separately tested qualities (such as ability or health) are not part of the judging in conformation shows.

As food

In China and South Vietnam dogs are a source of meat for humans.[127][128] Dog meat is consumed in some East Asian countries, including Korea, China, and Vietnam, a practice that dates back to antiquity.[158] It is estimated that 13–16 million dogs are killed and consumed in Asia every year.[159] Other cultures, such as Polynesia and pre-Columbian Mexico, also consumed dog meat in their history. However, Western, South Asian, African, and Middle Eastern cultures, in general, regard consumption of dog meat as taboo. In some places, however, such as in rural areas of Poland, dog fat is believed to have medicinal properties—being good for the lungs for instance.[160] Dog meat is also consumed in some parts of Switzerland.[161] Proponents of eating dog meat have argued that placing a distinction between livestock and dogs is western hypocrisy, and that there is no difference with eating the meat of different animals.[162][163][164][165]

In Korea, the primary dog breed raised for meat, the nureongi (누렁이), differs from those breeds raised for pets that Koreans may keep in their homes.[166]

The most popular Korean dog dish is gaejang-guk (also called bosintang), a spicy stew meant to balance the body's heat during the summer months; followers of the custom claim this is done to ensure good health by balancing one's gi, or vital energy of the body. A 19th century version of gaejang-guk explains that the dish is prepared by boiling dog meat with scallions and chili powder. Variations of the dish contain chicken and bamboo shoots. While the dishes are still popular in Korea with a segment of the population, dog is not as widely consumed as beef, chicken, and pork.[166]

Health risks to humans

In 2005, the WHO reported that 55,000 people died in Asia and Africa from rabies, a disease for which dogs are the most important vector.[167]

Citing a 2008 study, the U.S. Center for Disease Control estimated in 2015 that 4.5 million people in the USA are bitten by dogs each year.[168] A 2015 study estimated that 1.8% of the U.S. population is bitten each year.[169] In the 1980s and 1990s the US averaged 17 fatalities per year, while in the 2000s this has increased to 26.[170] 77% of dog bites are from the pet of family or friends, and 50% of attacks occur on the property of the dog's legal owner.[170]

A Colorado study found bites in children were less severe than bites in adults.[171] The incidence of dog bites in the US is 12.9 per 10,000 inhabitants, but for boys aged 5 to 9, the incidence rate is 60.7 per 10,000. Moreover, children have a much higher chance to be bitten in the face or neck.[172] Sharp claws with powerful muscles behind them can lacerate flesh in a scratch that can lead to serious infections.[173]

In the UK between 2003 and 2004, there were 5,868 dog attacks on humans, resulting in 5,770 working days lost in sick leave.[174]

In the United States, cats and dogs are a factor in more than 86,000 falls each year.[175] It has been estimated around 2% of dog-related injuries treated in UK hospitals are domestic accidents. The same study found that while dog involvement in road traffic accidents was difficult to quantify, dog-associated road accidents involving injury more commonly involved two-wheeled vehicles.[176]

Toxocara canis (dog roundworm) eggs in dog feces can cause toxocariasis. In the United States, about 10,000 cases of Toxocara infection are reported in humans each year, and almost 14% of the U.S. population is infected.[177] In Great Britain, 24% of soil samples taken from public parks contained T. canis eggs.[178] Untreated toxocariasis can cause retinal damage and decreased vision.[178] Dog feces can also contain hookworms that cause cutaneous larva migrans in humans.[179][180][181][182]

Health benefits for humans

The scientific evidence is mixed as to whether companionship of a dog can enhance human physical health and psychological wellbeing.[183] Studies suggesting that there are benefits to physical health and psychological wellbeing[184] have been criticised for being poorly controlled,[185] and finding that "[t]he health of elderly people is related to their health habits and social supports but not to their ownership of, or attachment to, a companion animal." Earlier studies have shown that people who keep pet dogs or cats exhibit better mental and physical health than those who do not, making fewer visits to the doctor and being less likely to be on medication than non-guardians.[186]

A 2005 paper states "recent research has failed to support earlier findings that pet ownership is associated with a reduced risk of cardiovascular disease, a reduced use of general practitioner services, or any psychological or physical benefits on health for community dwelling older people. Research has, however, pointed to significantly less absenteeism from school through sickness among children who live with pets."[183] In one study, new guardians reported a highly significant reduction in minor health problems during the first month following pet acquisition, and this effect was sustained in those with dogs through to the end of the study.[187]

In addition, people with pet dogs took considerably more physical exercise than those with cats and those without pets. The results provide evidence that keeping pets may have positive effects on human health and behaviour, and that for guardians of dogs these effects are relatively long-term.[187] Pet guardianship has also been associated with increased coronary artery disease survival, with human guardians being significantly less likely to die within one year of an acute myocardial infarction than those who did not own dogs.[188]

The health benefits of dogs can result from contact with dogs in general, and not solely from having dogs as pets. For example, when in the presence of a pet dog, people show reductions in cardiovascular, behavioral, and psychological indicators of anxiety.[189] Other health benefits are gained from exposure to immune-stimulating microorganisms, which, according to the hygiene hypothesis, can protect against allergies and autoimmune diseases. The benefits of contact with a dog also include social support, as dogs are able to not only provide companionship and social support themselves, but also to act as facilitators of social interactions between humans.[190] One study indicated that wheelchair users experience more positive social interactions with strangers when they are accompanied by a dog than when they are not.[191] In 2015, a study found that pet owners were significantly more likely to get to know people in their neighborhood than non-pet owners.[192]

The practice of using dogs and other animals as a part of therapy dates back to the late 18th century, when animals were introduced into mental institutions to help socialize patients with mental disorders.[193] Animal-assisted intervention research has shown that animal-assisted therapy with a dog can increase social behaviors, such as smiling and laughing, among people with Alzheimer's disease.[194] One study demonstrated that children with ADHD and conduct disorders who participated in an education program with dogs and other animals showed increased attendance, increased knowledge and skill objectives, and decreased antisocial and violent behavior compared to those who were not in an animal-assisted program.[195]

Medical detection dogs

Medical detection dogs are capable of detecting diseases by sniffing a person directly or samples of urine or other specimens. Dogs can detect odour in one part per trillion, as their brain's olfactory cortex is (relative to total brain size) 40 times larger than humans. Dogs may have as many as 300 million odour receptors in their nose, while humans may have only 5 million. Each dog is trained specifically for the detection of single disease from the blood glucose level indicative to diabetes to cancer. To train a cancer dog requires 6 months. A Labrador Retriever called Daisy has detected 551 cancer patients with an accuracy of 93 percent and received the Blue Cross (for pets) Medal for her life-saving skills.[196][197]

Shelters

Every year, between 6 and 8 million dogs and cats enter US animal shelters.[198] The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) estimates that approximately 3 to 4 million of those dogs and cats are euthanized yearly in the United States.[199] However, the percentage of dogs in US animal shelters that are eventually adopted and removed from the shelters by their new legal owners has increased since the mid-1990s from around 25% to a 2012 average of 40% among reporting shelters[200] (with many shelters reporting 60–75%).[201]

Cultural depictions

Dogs have been viewed and represented in different manners by different cultures and religions, over the course of history.

Mythology

In mythology, dogs often serve as pets or as watchdogs.[202]

In Greek mythology, Cerberus is a three-headed watchdog who guards the gates of Hades.[202] In Norse mythology, a bloody, four-eyed dog called Garmr guards Helheim.[202] In Persian mythology, two four-eyed dogs guard the Chinvat Bridge.[202] In Philippine mythology, Kimat who is the pet of Tadaklan, god of thunder, is responsible for lightning. In Welsh mythology, Annwn is guarded by Cŵn Annwn.[202]

In Hindu mythology, Yama, the god of death owns two watch dogs who have four eyes. They are said to watch over the gates of Naraka.[203] Hunter god Muthappan from North Malabar region of Kerala has a hunting dog as his mount. Dogs are found in and out of the Muthappan Temple and offerings at the shrine take the form of bronze dog figurines.[204]

The role of the dog in Chinese mythology includes a position as one of the twelve animals which cyclically represent years (the zodiacal dog).

Religion and culture

In Homer's epic poem the Odyssey, when the disguised Odysseus returns home after 20 years he is recognized only by his faithful dog, Argos, who has been waiting for his return.

In Islam, dogs are viewed as unclean because they are viewed as scavengers.[202] In 2015 city councillor Hasan Küçük of The Hague called for dog ownership to be made illegal in that city.[205] Islamic activists in Lérida, Spain, lobbied for dogs to be kept out of Muslim neighborhoods, saying their presence violated Muslims' religious freedom.[205] In Britain, police sniffer dogs are carefully used, and are not permitted to contact passengers, only their luggage. They are required to wear leather dog booties when searching mosques or Muslim homes.[205]

Jewish law does not prohibit keeping dogs and other pets.[206] Jewish law requires Jews to feed dogs (and other animals that they own) before themselves, and make arrangements for feeding them before obtaining them.[206] In Christianity, dogs represent faithfulness.[202]

In China, Korea, and Japan, dogs are viewed as kind protectors.[202]

Art

Cultural depictions of dogs in art extend back thousands of years to when dogs were portrayed on the walls of caves. Representations of dogs became more elaborate as individual breeds evolved and the relationships between human and canine developed. Hunting scenes were popular in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Dogs were depicted to symbolize guidance, protection, loyalty, fidelity, faithfulness, watchfulness, and love.[207]

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Dogs in art. |

See also

- Aging in dogs

- Toy Group

- Animal track

- Argos (dog)

- Dog in Chinese mythology

- Dogs in art

- Dog odor

- Dognapping

- Ethnocynology

- Hachikō–a notable example of dog loyalty

- Lost pet services

- Mountain dog

- Wolfdog

- Lists

References

- 1 2 3 4 Smithsonian - Animal Species of the World database. "Search for Canis lupus". Retrieved 28 September 2016.

- 1 2 3 Wang, Xiaoming; Tedford, Richard H.; Dogs: Their Fossil Relatives and Evolutionary History. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008

- 1 2 Lindblad-Toh, K.; Wade, C. M.; Mikkelsen, T. S.; Karlsson, E. K.; Jaffe, D. B.; Kamal, M.; Clamp, M.; Chang, J. L.; Kulbokas, E. J.; Zody, M. C.; Mauceli, E.; Xie, X.; Breen, M.; Wayne, R. K.; Ostrander, E. A.; Ponting, C. P.; Galibert, F.; Smith, D. R.; Dejong, P. J.; Kirkness, E.; Alvarez, P.; Biagi, T.; Brockman, W.; Butler, J.; Chin, C. W.; Cook, A.; Cuff, J.; Daly, M. J.; Decaprio, D.; et al. (2005). "Genome sequence, comparative analysis and haplotype structure of the domestic dog". Nature. 438 (7069): 803–819. Bibcode:2005Natur.438..803L. doi:10.1038/nature04338. PMID 16341006.

- 1 2 3 Fan, Zhenxin; Silva, Pedro; Gronau, Ilan; Wang, Shuoguo; Armero, Aitor Serres; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ramirez, Oscar; Pollinger, John; Galaverni, Marco; Ortega Del-Vecchyo, Diego; Du, Lianming; Zhang, Wenping; Zhang, Zhihe; Xing, Jinchuan; Vilà, Carles; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Godinho, Raquel; Yue, Bisong; Wayne, Robert K. (2016). "Worldwide patterns of genomic variation and admixture in gray wolves". Genome Research. 26 (2): 163–73. doi:10.1101/gr.197517.115. PMID 26680994.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Thalmann, O.; Shapiro, B.; Cui, P.; Schuenemann, V. J.; Sawyer, S. K.; Greenfield, D. L.; Germonpre, M. B.; Sablin, M. V.; Lopez-Giraldez, F.; Domingo-Roura, X.; Napierala, H.; Uerpmann, H.-P.; Loponte, D. M.; Acosta, A. A.; Giemsch, L.; Schmitz, R. W.; Worthington, B.; Buikstra, J. E.; Druzhkova, A.; Graphodatsky, A. S.; Ovodov, N. D.; Wahlberg, N.; Freedman, A. H.; Schweizer, R. M.; Koepfli, K.- P.; Leonard, J. A.; Meyer, M.; Krause, J.; Paabo, S.; et al. (2013). "Complete Mitochondrial Genomes of Ancient Canids Suggest a European Origin of Domestic Dogs". Science. 342 (6160): 871. doi:10.1126/science.1243650. PMID 24233726.

- 1 2 Vila, C.; Amorim, I. R.; Leonard, J. A.; Posada, D.; Castroviejo, J.; Petrucci-Fonseca, F.; Crandall, K. A.; Ellegren, H.; Wayne, R. K. (1999). "Mitochondrial DNA phylogeography and population history of the grey wolf Canis lupus". Molecular Ecology. 8 (12): 2089–103. doi:10.1046/j.1365-294x.1999.00825.x. PMID 10632860.

- 1 2 3 Vila, C. (1997). "Multiple and ancient origins of the domestic dog". Science. 276 (5319): 1687–9. doi:10.1126/science.276.5319.1687. PMID 9180076.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Freedman, Adam H.; Gronau, Ilan; Schweizer, Rena M.; Ortega-Del Vecchyo, Diego; Han, Eunjung; Silva, Pedro M.; Galaverni, Marco; Fan, Zhenxin; Marx, Peter; Lorente-Galdos, Belen; Beale, Holly; Ramirez, Oscar; Hormozdiari, Farhad; Alkan, Can; Vilà, Carles; Squire, Kevin; Geffen, Eli; Kusak, Josip; Boyko, Adam R.; Parker, Heidi G.; Lee, Clarence; Tadigotla, Vasisht; Siepel, Adam; Bustamante, Carlos D.; Harkins, Timothy T.; Nelson, Stanley F.; Ostrander, Elaine A.; Marques-Bonet, Tomas; Wayne, Robert K.; Novembre, John (16 January 2014). "Genome Sequencing Highlights Genes Under Selection and the Dynamic Early History of Dogs". PLOS Genetics. PLOS Org. 10 (1): e1004016. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004016. PMC 3894170

. PMID 24453982. Retrieved 8 December 2014.

. PMID 24453982. Retrieved 8 December 2014. - 1 2 3 4 5 6 Larson G, Bradley DG (2014). "How Much Is That in Dog Years? The Advent of Canine Population Genomics". PLOS Genetics. 10 (1): e1004093. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1004093. PMC 3894154

. PMID 24453989.

. PMID 24453989. - 1 2 Perri, Angela (2016). "A wolf in dog's clothing: Initial dog domestication and Pleistocene wolf variation". Journal of Archaeological Science. 68: 1. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2016.02.003.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Dewey, T. and S. Bhagat. 2002. "Canis lupus familiaris", Animal Diversity Web. Retrieved 6 January 2009.

- 1 2 Berns, G. S.; Brooks, A. M.; Spivak, M. (2012). Neuhauss, Stephan C. F, ed. "Functional MRI in Awake Unrestrained Dogs". PLoS ONE. 7 (5): e38027. Bibcode:2012PLoSO...738027B. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0038027. PMC 3350478

. PMID 22606363.

. PMID 22606363. - 1 2 Axelsson, E.; Ratnakumar, A.; Arendt, M. L.; Maqbool, K.; Webster, M. T.; Perloski, M.; Liberg, O.; Arnemo, J. M.; Hedhammar, Å.; Lindblad-Toh, K. (2013). "The genomic signature of dog domestication reveals adaptation to a starch-rich diet". Nature. 495 (7441): 360–364. Bibcode:2013Natur.495..360A. doi:10.1038/nature11837. PMID 23354050.

- ↑ Why are different breeds of dogs all considered the same species? - Scientific American. Nikhil Swaminathan. Accessed on August 28, 2016.

- ↑ "Domestic PetDog Classified By Linnaeus In 1758 As Canis Familiaris And Canis Familiarus Domesticus". www.encyclocentral.com. Retrieved 18 June 2008.

- ↑ Seebold, Elmar (2002). Kluge. Etymologisches Wörterbuch der deutschen Sprache. Berlin/New York: Walter de Gruyter. p. 207. ISBN 3-11-017473-1.

- ↑ "Dictionary of Etymology", Dictionary.com, s.v. dog, encyclopedia.com retrieved on 27 May 2009.

- ↑ Mallory, J. R. (1991). In search of the Indo-Europeans: language, archaeology and myth. London: Thames and Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27616-1.

- ↑ Broz, Vlatko (2008). "Diachronic Investigations of False Friends". Contemporary Linguistics (Suvremena lingvistika). 66 (2): 199–222.

- ↑ René Dirven; Marjolyn Verspoor (2004). Cognitive exploration of language and linguistics. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 215–216. ISBN 978-90-272-1906-0.

- ↑ "The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition". www.bartleby.com. Archived from the original on 18 October 2006. Retrieved 30 November 2006.

- ↑ Gould, Jean (1978). All about dog breeding for quality and soundness. London, Eng: Pelham. ISBN 0-7207-1064-2.

- ↑ "Dog". Dictionary.com.

- ↑ Harper, Douglas. "canine". Online Etymology Dictionary.

- ↑ Linnaeus, Carolus (1758). Systema naturae per regna tria naturae:secundum classes, ordines, genera, species, cum characteribus, differentiis, synonymis, locis. 1 (10th ed.). Holmiae (Laurentii Salvii). p. 38. Retrieved 11 November 2015.

- ↑ "Familiar". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2014.

- ↑ "Lupus". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. 2014.

- ↑ Van Gelder; Richard G. (1978). "A Review of Canid Classification" (PDF). 2646. American Museum of Natural History, Central Park West, 79th Street, New York: 2.

- ↑ Honaki, J, ed. (1982). Mammal species of the world: A taxonomic and geographic reference (First Edition). Allen Press and the Association of Systematics Collections. p. 245.Page 245- "COMMENTS: "Probably ancestor of and conspecific with the domestic dog, familiaris. Canis familiaris has page priority over Canis lupus, but both were published simultaneously in Linnaeus (1758), and Canis lupus has been universally used for this species."

- ↑ Wozencraft, W.C. (2005). "Order Carnivora". In Wilson, D.E.; Reeder, D.M. Mammal Species of the World: A Taxonomic and Geographic Reference (3rd ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 532–628. ISBN 978-0-8018-8221-0. OCLC 62265494.

- ↑ Gentry, Anthea; Clutton-Brock, Juliet; Groves, Colin P. (2004). "The naming of wild animal species and their domestic derivatives". Journal of Archaeological Science. 31 (5): 645–651. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2003.10.006.

- ↑ Includes Vila (1999) p71, Coppinger (2001) p281, Nowak (2003) p257, Crockford (2006) p100, Bjornenfeldt (2007) p21, Nolan (2009) p16, Druzhkova (2013) p2, and an internet search on Canis familiaris reveals many others.

- ↑ vonHoldt, B. (2010). "Genome-wide SNP and haplotype analyses reveal a rich history underlying dog domestication". Nature. 464 (7290): 898–902. doi:10.1038/nature08837. PMC 3494089

. PMID 20237475.

. PMID 20237475. - ↑ Liane Giemsch, Susanne C. Feine, Kurt W. Alt, Qiaomei Fu, Corina Knipper, Johannes Krause, Sarah Lacy, Olaf Nehlich, Constanze Niess, Svante Pääbo, Alfred Pawlik, Michael P. Richards, Verena Schünemann, Martin Street, Olaf Thalmann, Johann Tinnes, Erik Trinkaus & Ralf W. Schmitz. "Interdisciplinary investigations of the late glacial double burial from Bonn-Oberkassel". Hugo Obermaier Society for Quaternary Research and Archaeology of the Stone Age: 57th Annual Meeting in Heidenheim, 7th – 11th April 2015, 36-37

- ↑ Germonpre, M. (2009). "Fossil dogs and wolves from Palaeolithic sites in Belgium, the Ukraine and Russia: Osteometry, ancient DNA and stable isotopes". Journal of Archaeological Science. 36 (2): 473–490. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2008.09.033.

- 1 2 3 4 Machugh, David E.; Larson, Greger; Orlando, Ludovic (2016). "Taming the Past: Ancient DNA and the Study of Animal Domestication". Annual Review of Animal Biosciences. 5. doi:10.1146/annurev-animal-022516-022747.

- ↑ Shannon, L (2015). "Genetic structure in village dogs reveals a Central Asian domestication origin". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 112 (44): 201516215. doi:10.1073/pnas.1516215112.

- ↑ Wang, G (2015). "Out of southern East Asia: the natural history of domestic dogs across the world". Cell Research. 26 (1): 21–33. doi:10.1038/cr.2015.147. PMC 4816135

. PMID 26667385.

. PMID 26667385. - ↑ Frantz, L. A. F.; Mullin, V. E.; Pionnier-Capitan, M.; Lebrasseur, O.; Ollivier, M.; Perri, A.; Linderholm, A.; Mattiangeli, V.; Teasdale, M. D.; Dimopoulos, E. A.; Tresset, A.; Duffraisse, M.; McCormick, F.; Bartosiewicz, L.; Gal, E.; Nyerges, E. A.; Sablin, M. V.; Brehard, S.; Mashkour, M.; b l Escu, A.; Gillet, B.; Hughes, S.; Chassaing, O.; Hitte, C.; Vigne, J.-D.; Dobney, K.; Hanni, C.; Bradley, D. G.; Larson, G. (2016). "Genomic and archaeological evidence suggest a dual origin of domestic dogs". Science. 352 (6290): 1228. doi:10.1126/science.aaf3161. PMID 27257259.

- ↑ Grimm, David (2016). "Dogs may have been domesticated more than once". Science. doi:10.1126/science.aaf5755.

- ↑ "World's Largest Dog". Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ "Guinness World Records – Tallest Dog Living". Guinness World Records. 31 August 2004. Archived from the original on 11 July 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ↑ Nießner, Christine; Denzau, Susanne; Malkemper, Erich Pascal; Gross, Julia Christina; Burda, Hynek; Winklhofer, Michael; Peichl, Leo (2016). "Cryptochrome 1 in Retinal Cone Photoreceptors Suggests a Novel Functional Role in Mammals". Scientific Reports. 6: 21848. doi:10.1038/srep21848. PMC 4761878

. PMID 26898837.

. PMID 26898837. - ↑ Magnetoreception molecule found in the eyes of dogs and primates MPI Brain Research, 22 February 2016

- ↑ Klappenbach, Laura (2008). "What is Counter Shading?". About.com. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ Cunliffe, Juliette (2004). "Coat Types, Colours and Markings". The Encyclopedia of Dog Breeds. Paragon Publishing. pp. 20–23. ISBN 0-7525-8276-3.

- ↑ "The Case for Tail Docking". Council of Docked Breeds. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ "Bourbonnais pointer or 'short tail pointer'". Braquedubourbonnais.info. Retrieved 19 December 2012.

- ↑ "Plants poisonous to dogs – Sunset". Sunset.

- ↑ Sources vary on which of these are considered the most significant toxic item.

- ↑ Murphy, L. A.; Coleman, A. E. (2012). "Xylitol Toxicosis in Dogs". Veterinary Clinics of North America: Small Animal Practice. 42 (2): 307–312. doi:10.1016/j.cvsm.2011.12.003.

- ↑ "Toxic Foods and Plants for Dogs". entirelypets.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Drs. Foster & Smith. "Foods to Avoid Feeding Your Dog". peteducation.com. Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ Fogle, Bruce (1974). Caring For Your Dog.

- ↑ Ward, Ernie. "Diseases shared by humans and pets". Dogtime.com. Retrieved 2 October 2010.

- ↑ O'Neill, D. G.; Church, D. B.; McGreevy, P. D.; Thomson, P. C.; Brodbelt, D. C. (2013). "Longevity and mortality of owned dogs in England". The Veterinary Journal. 198 (3): 638–643. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2013.09.020. PMID 24206631.

- ↑ "Kennel Club/British Small Animal Veterinary Association Scientific Committee". 2004. Retrieved 5 July 2007.

- 1 2 Proschowsky, H. F.; H. Rugbjerg & A. K. Ersbell (2003). "Mortality of purebred and mixed-breed dogs in Denmark". Preventive Veterinary Medicine. 58 (1–2): 63–74. doi:10.1016/S0167-5877(03)00010-2. PMID 12628771.

- 1 2 Michell AR (1999). "Longevity of British breeds of dog and its relationships with sex, size, cardiovascular variables and disease". The Veterinary Record. 145 (22): 625–9. doi:10.1136/vr.145.22.625. PMID 10619607.

- 1 2 3 4 Compiled by Cassidy; K. M. "Dog Longevity Web Site, Breed Data page". Retrieved 8 July 2007.

- ↑ Patronek GJ, Waters DJ, Glickman LT (1997). "Comparative longevity of pet dogs and humans: implications for gerontology research". The Journals of Gerontology. Series a, Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences. 52 (3): B171–8. doi:10.1093/gerona/52A.3.B171. PMID 9158552.

- ↑ "Pusuke, world's oldest living dog, dies in Japan". 7 December 2011.

- ↑ "Sexual Maturity — Spay and Neuter". Buffalo.com. Archived from the original on 10 June 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ Concannon, P; Tsutsui, T; Shille, V (2001). "Embryo development, hormonal requirements and maternal responses during canine pregnancy". Journal of reproduction and fertility. Supplement. 57: 169–79. PMID 11787146.

- ↑ "Dog Development – Embryology". Php.med.unsw.edu.au. 16 June 2013. Retrieved 22 September 2013.

- ↑ "Gestation in dogs". Retrieved 24 March 2013.

- ↑ "HSUS Pet Overpopulation Estimates". The Humane Society of the United States. Retrieved 22 October 2008.

- ↑ "French Bulldog Pet Care Guide". Archived from the original on 26 July 2011. Retrieved 7 January 2008.

- ↑ "Top 10 reasons to spay/neuter your pet". American Society for Prevention of Cruelty to Animals. Retrieved 16 May 2007.

- ↑ Mahlow, Jane C. (1999). "Estimation of the proportions of dogs and cats that are surgically sterilized". Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association. 215 (5): 640–643. PMID 10476708.

Although the cause of pet overpopulation is multifaceted, the lack of guardians choosing to spay or neuter their animals is a major contributing factor.

- ↑ Heidenberger, E; Unshelm, J (Feb 1990). "Changes in the behavior of dogs after castration". Tierärztliche Praxis (in German). 18 (1): 69–75. ISSN 0303-6286. PMID 2326799.

- ↑ Morrison, Wallace B. (1998). Cancer in Dogs and Cats (1st ed.). Williams and Wilkins. ISBN 0-683-06105-4.

- ↑ Arnold S (1997). "[Urinary incontinence in castrated bitches. Part 1: Significance, clinical aspects and etiopathogenesis]". Schweizer Archiv für Tierheilkunde (in German). 139 (6): 271–6. PMID 9411733.

- ↑ Johnston, SD; Kamolpatana, K; Root-Kustritz, MV; Johnston, GR (Jul 2000). "Prostatic disorders in the dog". Anim. Reprod. Sci. 60–61: 405–15. doi:10.1016/S0378-4320(00)00101-9. ISSN 0378-4320. PMID 10844211.

- ↑ Root-Kustritz MV (Dec 2007). "Determining the optimal age for gonadectomy of dogs and cats". JAVMA. 231 (11): 1665–1675. doi:10.2460/javma.231.11.1665. ISSN 0003-1488. PMID 18052800.

- ↑ Leroy G (2011). "Genetic diversity, inbreeding and breeding practices in dogs: results from pedigree analyses". Vet. J. 189 (2): 177–82. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2011.06.016. PMID 21737321.

- ↑ Leroy G, Phocas F, Hedan B, Verrier E, Rognon X (2015). "Inbreeding impact on litter size and survival in selected canine breeds". Vet. J. 203 (1): 74–8. doi:10.1016/j.tvjl.2014.11.008. PMID 25475165.

- ↑ Gresky C, Hamann H, Distl O (2005). "[Influence of inbreeding on litter size and the proportion of stillborn puppies in dachshunds]". Berl. Munch. Tierarztl. Wochenschr. (in German). 118 (3–4): 134–9. PMID 15803761.

- 1 2 van der Beek S, Nielen AL, Schukken YH, Brascamp EW (1999). "Evaluation of genetic, common-litter, and within-litter effects on preweaning mortality in a birth cohort of puppies". Am. J. Vet. Res. 60 (9): 1106–10. PMID 10490080.

- ↑ Charlesworth D, Willis JH (2009). "The genetics of inbreeding depression". Nat. Rev. Genet. 10 (11): 783–96. doi:10.1038/nrg2664. PMID 19834483.

- ↑ Bernstein H, Hopf FA, Michod RE (1987). "The molecular basis of the evolution of sex". Adv. Genet. Advances in Genetics. 24: 323–70. doi:10.1016/s0065-2660(08)60012-7. ISBN 9780120176243. PMID 3324702.

- ↑ Smith, B.; Litchfield, C. (2010). "How well do dingoes (Canis dingo) perform on the detour task". Animal Behaviour. 80: 155–162. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.04.017.

- ↑ Miklósi, A; Kubinyi, E; Topál, J; Gácsi, M; Virányi, Z; Csányi, V (Apr 2003). "A simple reason for a big difference: wolves do not look back at humans, but dogs do". Curr Biol. 13 (9): 763–6. doi:10.1016/S0960-9822(03)00263-X. PMID 12725735.

- ↑ Brian Hare, Vanessa Woods (8 February 2013), "What Are Dogs Saying When They Bark? [Excerpt]", Scientific America, retrieved 17 March 2015

- ↑ Amy Crawford. "Why Dogs are More Like Humans Than Wolves". Smithsonian. Retrieved 2 September 2015.

- ↑ Levitis, Daniel A.; Lidicker, William Z. Jr.; Freund, Glenn (June 2009). "Behavioural biologists do not agree on what constitutes behaviour" (PDF). Animal Behaviour. 78 (1): 103–10. doi:10.1016/j.anbehav.2009.03.018.

- ↑ Tomasello, M.; Kaminski, J. (2009). "Like Infant, Like Dog". Science. 325 (5945): 1213–4. doi:10.1126/science.1179670. PMID 19729645.

- ↑ Coren, Stanley "How To Speak Dog: Mastering the Art of Dog-Human Communication" 2000 Simon & Schuster, New York.

- ↑ Skoglund, P. (2015). "Ancient wolf genome reveals an early divergence of domestic dog ancestors and admixture into high-latitude breeds". Current Biology. 25 (11): 1515–9. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2015.04.019. PMID 26004765.

- ↑ Elliot, D. G., and M. Wong. 1972. Acid phosphatase, handy enzyme that separates the dog from the wolf. Acta Biologica et Medica Germanica 28:957 – 62

- ↑ Mech, D. L. (1974). "Canis lupus" (PDF). Mammalian Species. 37 (37): 1–6. doi:10.2307/3503924. JSTOR 3503924.

- 1 2 Serpell, James (1995). "Origins of the dog: domestication and early history". The Domestic Dog. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press. ISBN 0-521-41529-2.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1987). A Natural History of Domesticated Mammals. British Museum (Natural History), p. 24, ISBN 0-521-34697-5

- ↑ Rincon, Paul (8 April 2004), Claws reveal wolf survival threat, BBC News, retrieved 12 December 2014

- ↑ Mech & Boitani 2003, p. 257

- 1 2 3 4 Coppinger, Ray (2001). Dogs: a Startling New Understanding of Canine Origin, Behavior and Evolution. New York: Scribner. ISBN 0-684-85530-5.

- ↑ Lopez, Barry (1978). Of wolves and men. New York: Scribner Classics. p. 320. ISBN 0-7432-4936-4.

- 1 2 Spady TC, Ostrander EA (January 2008). "Canine Behavioral Genetics: Pointing Out the Phenotypes and Herding up the Genes". American Journal of Human Genetics. 82 (1): 10–8. doi:10.1016/j.ajhg.2007.12.001. PMC 2253978

. PMID 18179880.

. PMID 18179880. - 1 2 The Complete dog book: the photograph, history, and official standard of every breed admitted to AKC registration, and the selection, training, breeding, care, and feeding of pure-bred dogs. New York, N.Y: Howell Book House. 1992. ISBN 0-87605-464-5.

- ↑ Serpell J, Duffy D. Dog Breeds and Their Behavior. In: Domestic Dog Cognition and Behavior. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer; 2014

- 1 2 3 4 5 Cagan, Alex; Blass, Torsten (2016). "Identification of genomic variants putatively targeted by selection during dog domestication". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 16. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0579-7.

- ↑ Almada RC, Coimbra NC. Recruitment of striatonigral disinhibitory and nigrotectal inhibitory GABAergic pathways during the organization of defensive behavior by mice in a dangerous environment with the venomous snake Bothrops alternatus [ Reptilia , Viperidae ] Synapse 2015:n/a–n/a

- ↑ Coppinger R, Schneider R: Evolution of working dogs. The domestic dog: Its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people. Cambridge: Cambridge University press, 1995.

- ↑ Gompper, Matthew E. (2013). "The dog–human–wildlife interface: assessing the scope of the problem". In Gompper, Matthew E. Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation. Oxford University Press. pp. 9–54.

- 1 2 3 4 Lescureux, Nicolas; Linnell, John D.C. (2014). "Warring brothers: The complex interactions between wolves (Canis lupus) and dogs (Canis familiaris) in a conservation context". Biological Conservation. 171: 232–245. doi:10.1016/j.biocon.2014.01.032.

- ↑ Laveaux, C.J. & King of Prussia, F (1789). The life of Frederick the Second, King of Prussia: To which are added observations, Authentic Documents, and a Variety of Anecdotes. J. Derbett London.

- ↑ Ortolani, A (2009). "Ethiopian village dogs: Behavioural responses to a stranger's approach". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 119 (3–4): 210–218. doi:10.1016/j.applanim.2009.03.011.

- ↑ Udell, M. A. R.; Dorey, N. R.; Wynne, C. D. L. (2010). "What did domestication do to dogs? A new account of dogs' sensitivity to human actions". Biological Reviews. 85 (2): 327–45. doi:10.1111/j.1469-185X.2009.00104.x. PMID 19961472.

- ↑ Vanak, A.T., Dickman, C.R., Silva-Rodriguez, E.A., Butler, J.R.A., Ritchie, E.G., 2014. Top-dogs and under-dogs: competition between dogs and sympatric carnivores. In: Gompper, M.E. (Ed.), Free-Ranging Dogs and Wildlife Conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, pp. 69–93

- ↑ Boitani, L., 1983. Wolf and dog competition in Italy. Acta Zool. Fennica 174, 259–264

- 1 2 Boitani, Luigi; Mech, L. David (2003). Wolves: behavior, ecology, and conservation. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 305–306. ISBN 0-226-51696-2.

- ↑ Graves, Will (2007). Wolves in Russia: Anxiety throughout the ages. Calgary: Detselig Enterprises. p. 222. ISBN 1-55059-332-3.

- ↑ Kojola, I.; Ronkainen, S.; Hakala, A.; Heikkinen, S.; Kokko, S. "Interactions between wolves Canis lupus and dogs C. familiaris in Finland". Nordic Council for Wildlife Research.

- ↑ Scott, Jonathan; Scott, Angela (2006). Big Cat Diary: Leopard. London: Collins. p. 108. ISBN 0-00-721181-3.

- ↑ Perry, Richard (1965). The World of the Tiger. p. 260. ASIN: B0007DU2IU.

- ↑ "Striped Hyaena Hyaena (Hyaena) hyaena (Linnaeus, 1758)". IUCN Species Survival Commission Hyaenidae Specialist Group. Archived from the original on 28 September 2007. Retrieved 21 May 2008.

- ↑ Marc Bekoff; Dale Jamieson (2006). "Ethics and the Study of Carnivores". Animal passions and beastly virtues. Temple University Press. ISBN 978-1-59213-348-2.

- ↑ Hazard, Evan B. (1982). "Order Carnivora". The mammals of Minnesota. U of Minnesota Press. ISBN 978-0-8166-0952-9.

- ↑ S. G. Pierzynowski; R. Zabielski (1999). Biology of the pancreas in growing animals. Volume 28 of Developments in animal and veterinary sciences. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 417. ISBN 978-0-444-50217-9.

- ↑ National Research Council (U.S.). Ad Hoc Committee on Dog and Cat Nutrition (2006). Nutrient requirements of dogs and cats. National Academies Press. p. 137. ISBN 978-0-309-08628-8.

- ↑ Smith, Cheryl S. (2008). "Chapter 6, Omnivores Together". Grab Life by the Leash: A Guide to Bringing Up and Bonding with Your Four-Legged Friend. John Wiley and Sons. ISBN 978-0-470-17882-9.

- ↑ Savolainen P, Zhang YP, Luo J, Lundeberg J, Leitner T (November 2002). "Genetic evidence for an East Asian origin of domestic dogs". Science. 298 (5598): 1610–3. Bibcode:2002Sci...298.1610S. doi:10.1126/science.1073906. PMID 12446907.

- ↑ The Merriam-Websterial Staff, ed. (1967). Webster's Third New International Dictionary of the English Language, Unabridged. Springfield, MA U.S.A.: G&C Merriam Company. p. 2476.

type (4a) the combination of character that fits an individual to a particular use or function (a strong horse of the draft type)

- 1 2 3 Parker, Heidi G.; Kim, Lisa V.; Sutter, Nathan B.; Carlson, Scott; Lorentzen, Travis D.; Malek, Tiffany B.; Johnson, Gary S.; DeFrance, Hawkins B.; Ostrander, Elaine A.; Kruglyak, Leonid (2004). "Genetic structure of the purebred domestic dog". Science. 304 (5674): 1160–4. Bibcode:2004Sci...304.1160P. doi:10.1126/science.1097406. PMID 15155949.

- ↑ Ostrander, Elaine A. (September–October 2007). "Genetics and the Shape of Dogs; Studying the new sequence of the canine genome shows how tiny genetic changes can create enormous variation within a single species". American Scientist (online). www.americanscientist.org. pp. also see chart page 4. Retrieved 22 September 2008.

- 1 2 Miklósi, Adám (2007). Dog Behaviour, Evolution, and Cognition. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199295852.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-929585-2.

- 1 2 Wingfield-Hayes, Rupert (29 June 2002). "China's taste for the exotic". BBC News.

- 1 2 "Vietnam's dog meat tradition". BBC News. 31 December 2001.

- 1 2 3 Groves, Colin (1999). "The Advantages and Disadvantages of Being Domesticated". Perspectives in Human Biology. 4: 1–12. ISSN 1038-5762.

- ↑ Travels in Central Asia by Meer Izzut-oollah in the Years 1812-13. Translated by Captain Henderson. Calcutta, 1872, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Tacon, Paul; Pardoe, Colin (2002). "Dogs make us human". Nature Australia. 27 (4): 52–61.

- ↑ Ruusila, Vesa; Pesonen, Mauri (2004). "Interspecific cooperation in human (Homo sapiens) hunting: the benefits of a barking dog (Canis familiaris)" (PDF). Annales Zoologici Fennici. 41 (4): 545–9.

- ↑ Newby, Jonica (1997). The Pact for Survival. Sydney: ABC Books. ISBN 0-7333-0581-4.

- 1 2 A History of Dogs in the Early Americas, Marion Schwartz, 1998, 260 p., ISBN 978-0-300-07519-9, Yale University Press

- ↑ "The University of Maine – UMaine News – UMaine Student Finds Oldest Known Domesticated Dog in Americas". Umaine.edu. 11 January 2011. Retrieved 4 July 2013.

- ↑ Derr, Mark (2004). A dogs history of America. North Point Press. p.12

- 1 2 Derr, Mark (1997). Dog's Best Friend. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 0-226-14280-9.

- ↑ Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1995), "Origins of the dog: domestication and early history", in Serpell, James, The domestic dog: its evolution, behaviour and interactions with people, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-41529-2

- ↑ Franklin, A (2006). "Be[a]ware of the Dog: a post-humanist approach to housing". Housing Theory and Society. 23 (3): 137–156. doi:10.1080/14036090600813760. ISSN 1403-6096.

- ↑ Katz, Jon (2003). The New Work of Dogs. New York: Villard Books. ISBN 0-375-76055-5.

- ↑ Haraway, Donna (2003). The Companion Species manifesto: Dogs, People and Significant Otherness. Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press. ISBN 0-9717575-8-5.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Power, Emma (2008). "Furry Families: Making a Human-Dog Family through Home". Social and Cultural Geography. 9 (5): 535–555. doi:10.1080/14649360802217790.

- 1 2 3 Nast, Heidi J. (2006). "Loving ... Whatever: Alienation, Neoliberalism and Pet-Love in the Twenty-First Century". ACME: an International E-Journal for Critical Geographies. 5 (2): 300–327. ISSN 1492-9732.

- ↑ "A Brief History of Dog Training". Dog Zone. 3 June 2007. Retrieved 19 February 2010.

- ↑ Jackson Schebetta, Lisa (2009). "Mythologies and Commodifications of Dominion in The Dog Whisperer with Cesar Millan". Journal for Critical Animal Studies. Institute for Critical Animal Studies. 7 (1): 107–131. ISSN 1948-352X.

- ↑ Bradshaw, John; Blackwell, Emily J.; Casey, Rachel A. (2009). "Dominance in domestic dogs: useful construct or bad habit?". Journal of Veterinary Behavior. Elsevier. 4 (3): 135–144. doi:10.1016/j.jveb.2008.08.004. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2010.

- ↑ Tannen, Deborah (2004). "Talking the Dog: Framing Pets as Interactional Resources in Family Discourse". Research on Language and Social Interaction. 37 (4): 399–420. doi:10.1207/s15327973rlsi3704_1. ISSN 1532-7973.

- ↑ "U.S. Pet Ownership Statistics". Retrieved 24 June 2010.

- ↑ James Edgar (21 February 2014). "Dogs and humans respond to voices in same way". The Daily Telegraph. London.

- ↑ "The Story of Old Drum". Cedarcroft Farm Bed & Breakfast — Warrensburg, MO. Retrieved 29 November 2006.

- ↑ Williams, Tully (2007). Working Sheep Dogs. Collingwood, Vic.: CSIRO Publishing. ISBN 0-643-09343-5.

- ↑ "sputnik". Retrieved 25 September 2013.

- ↑ Solovyov, Dmitry; Pearce, Tim (ed.) (11 April 2008). "Russia fetes dog Laika, first earthling in space". Reuters.

- ↑ "Psychiatric Service Dog Society". Psychdog.org. 1 October 2005. Retrieved 21 December 2010.

- ↑ "About Guide Dogs – Assistance Dogs International". Assistancedogsinternational.org. Retrieved 21 December 2010.