Mount Sharp

|

The rover Curiosity landed on August 6, 2012, near the base of Aeolis Mons. | |

| Location | Gale crater on Mars |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 5°05′S 137°51′E / 5.08°S 137.85°ECoordinates: 5°05′S 137°51′E / 5.08°S 137.85°E |

| Peak | Aeolis Mons – 5.5 km (18,000 ft) high[1] |

| Discoverer | NASA in the 1970s |

| Eponym |

Aeolis Mons – Aeolis albedo feature Mount Sharp – Robert P. Sharp (1911–2004) |

Mount Sharp, officially Aeolis Mons (IPA: [ˈiːəlɨs ˈmɒnz]), is a mountain on Mars. It forms the central peak within Gale crater and is located around 5°05′S 137°51′E / 5.08°S 137.85°E, rising 5.5 km (18,000 ft) high from the valley floor. It has the ID of 15,000 in the Gazetteer of Planetary Nomenclature from the US Geological Survey.[2]

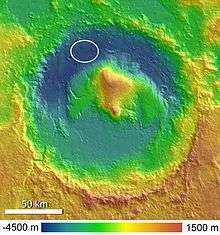

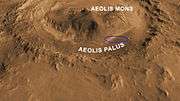

On August 6, 2012, Curiosity (the Mars Science Laboratory rover) landed in "Yellowknife" Quad 51[3][4][5][6] of Aeolis Palus,[7] next to the mountain. NASA named the landing site Bradbury Landing on August 22, 2012.[8] Aeolis Mons is a primary goal for scientific study.[9] On June 5, 2013, NASA announced that Curiosity would begin a 8 km (5.0 mi) journey from the Glenelg area to the base of Aeolis Mons. On November 13, 2013, NASA announced that an entryway Curiosity would traverse on its way to Aeolis Mons was to be named "Murray Buttes", in honor of planetary scientist Bruce C. Murray (1931–2013).[10] The trip was expected to take about a year and would include stops along the way to study the local terrain.[11][12][13]

On September 11, 2014, NASA announced that the Curiosity rover had reached Aeolis Mons, the rover mission's long-term prime destination.[14][15]

On October 5, 2015, possible recurrent slope lineae, wet brine flows, were reported on Mount Sharp near Curiosity.[16]

As of December 11, 2016, Curiosity has been on the planet Mars for 1546 sols (1588 days) since landing on August 6, 2012. (See Current status.)

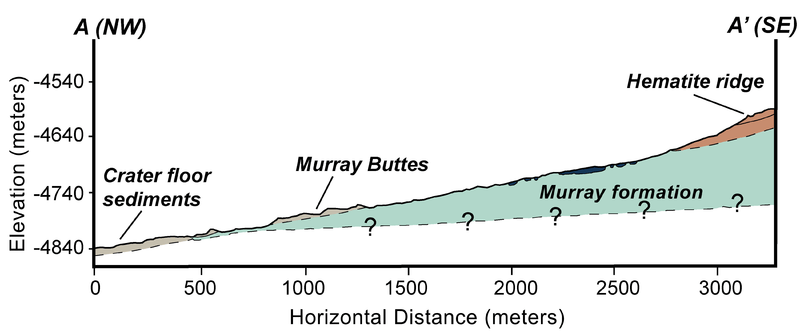

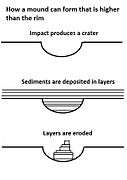

Formation

The mountain appears to be an enormous mound of eroded sedimentary layers sitting on the central peak of Gale. It rises 5.5 km (18,000 ft) above the northern crater floor and 4.5 km (15,000 ft) above the southern crater floor, higher than the southern crater rim. The sediments may have been laid down over an interval of 2 billion years,[17] and may have once completely filled the crater. Some of the lower sediment layers may have originally been deposited on a lake bed,[17] while observations of possibly cross-bedded strata in the upper mound suggest aeolian processes.[18] However, this issue is debated,[19][20] and the origin of the lower layers remains unclear.[18] If katabatic wind deposition played the predominant role in the emplacement of the sediments, as suggested by reported 3 degree radial slopes of the mound's layers, erosion would have come into play largely to place an upper limit on the mound's growth.[21][22]

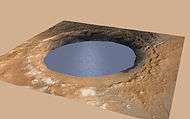

On December 8, 2014, a panel of NASA scientists discussed (archive 62:03) the latest observations of Curiosity about how water may have helped shape the landscape of Mars, including Aeolis Mons, and had a climate long ago that could have produced long-lasting lakes at many Martian locations.[23][24][25]

On October 8, 2015, NASA confirmed that lakes and streams existed in Gale crater 3.3 - 3.8 billion years ago delivering sediments to build up the lower layers of Mount Sharp.[26][27]

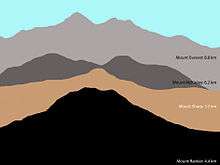

Understanding size

| Mountain | km high |

|---|---|

| Aeolis | 5.5 |

| Huygens | 5.5 |

| Denali | 5.5 (btp) |

| Blanc | 4.8 (asl) |

| Uhuru | 4.6 (btp) |

| Fuji | 3.8 (asl) |

| Zugspitze | 3 |

Aeolis Mons is 5.5 km (18,000 ft) high, about the same height as Mons Huygens, the tallest lunar mountain, and taller than Mons Hadley visited by Apollo 15. The tallest mountain known in the Solar System is in Rheasilvia crater on the asteroid Vesta, which contains a central mound that rises 22 km (14 mi; 72,000 ft) high; Olympus Mons on Mars is nearly the same height, at 21.9 km (13.6 mi; 72,000 ft) high.

In comparison, Mount Everest rises to 8.8 km (29,000 ft) altitude above sea level (asl), but is only 4.6 km (15,000 ft) (base-to-peak) (btp).[29] Africa's Mount Kilimanjaro is about 5.9 km (19,000 ft) altitude above sea level to the Uhuru peak;[30] also 4.6 km base-to-peak.[31] America's Mt. McKinley, also known as Denali, has a base-to-peak of 5.5 km (18,000 ft).[32] The Franco-Italian Mont Blanc/Monte Bianco is 4.8 km (16,000 ft) in altitude above sea level,[33][34] Mount Fuji, which overlooks Tokyo, Japan, is about 3.8 km (12,000 ft) altitude. Compared to the Andes, Aeolis Mons would rank outside the hundred tallest peaks, being roughly the same height as Argentina's Cerro Pajonal; the peak is higher than any above sea level in Oceania, but base-to peak it is considerably shorter than Hawaii's Mauna Kea and its neighbors.

Name

Discovered in the 1970s, the mountain remained nameless for perhaps 40 years. When it became a likely landing site, it was given various labels; for example, in 2010 a NASA photo caption called it "Gale crater mound".[35] In March 2012, NASA unofficially named it "Mount Sharp", for American geologist Robert P. Sharp.[1][36]

The International Astronomical Union, which is responsible for planetary nomenclature for its participants, names large Martian mountains after the Classical albedo feature in which it is located, not for people. In May 2012 the IAU thus named the mountain Aeolis Mons, and gave the name Aeolis Palus to the crater floor plain between the northern wall of Gale and the northern foothills of the mountain.[1][37][38][39] In recognition of NASA and in honour of Sharp, the IAU gave the name "Robert Sharp" to a large crater (150 km (93 mi) in diameter), located about 260 km (160 mi) west of Gale, following its standard practice of naming large craters after scientists.

NASA and the ESA[40] continue to refer to the mountain as "Mount Sharp" in press conferences and press releases. This is similar to other informal names, such as the Columbia Hills near one of the Mars Exploration Rover landing sites. Sky & Telescope explained the rationales of the two names to their readers in August 2012, and held an informal poll to newsletter readers. Over 2700 voted and picked Aeolis Mons over Mount Sharp by 57% to 43%.[36] The official name, "Aeolis Mons", is recorded by the United States Geological Survey.[38]

Aeolis is the ancient name of the Izmir region in western Turkey.

Spacecraft exploration

On December 16, 2014, NASA reported detecting, based on measurements by the Curiosity rover, an unusual increase, then decrease, in the amounts of methane in the atmosphere of the planet Mars; as well as, detecting Martian organic chemicals in powder drilled from a rock by the Curiosity rover. Also, based on deuterium to hydrogen ratio studies, much of the water at Gale Crater on Mars was found to have been lost during ancient times, before the lakebed in the crater was formed; afterwards, large amounts of water continued to be lost.[41][42][43]

Curiosity mission

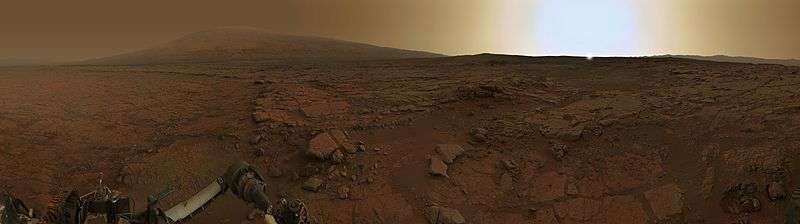

| Curiosity at Aeolis Mons |

|---|

|

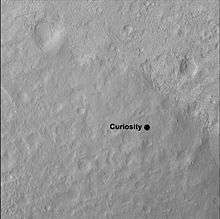

As of December 11, 2016, Curiosity has been on the planet Mars for 1546 sols (1588 total days; 4 years, 127 days) since landing on August 6, 2012. Since September 11, 2014, Curiosity has been exploring the slopes of Mount Sharp,[14][15] where more information about the history of Mars is expected to be found.[44] As of October 3, 2016, the rover has traveled over 11.7 km (7.3 mi)[45] to, and around, the mountain base since leaving its "start" point in Yellowknife Bay on July 4, 2013.[45]

(February 18, 2014/Sol 547).

(October 3, 2016/Sol 1478).

(November 23, 2014/Sol 817).[11][12][13]

| Curiosity at Aeolis Mons |

|---|

(MRO; HiRISE; December 13, 2014). |

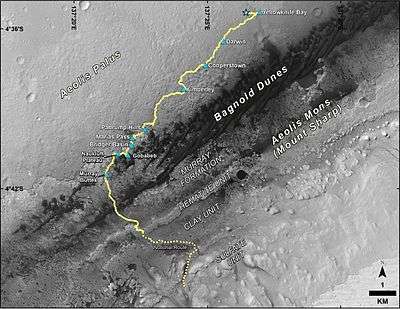

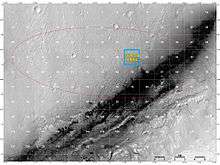

Overview map - blue oval marks "Base of Aeolis Mons" (August 17, 2012).

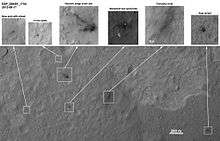

Overview map - blue oval marks "Base of Aeolis Mons" (August 17, 2012). Traverse map - route from Landing to slopes on Aeolis Mons (September 11, 2014).

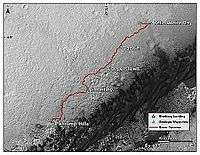

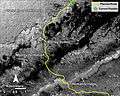

Traverse map - route from Landing to slopes on Aeolis Mons (September 11, 2014). Close-up Map - new route (yellow) - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014).

Close-up Map - new route (yellow) - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014). Close-up map - new route (yellow) - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014).

Close-up map - new route (yellow) - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014). Close-up map - Aeolis Mons slopes - with few craters (bottom) (September 11, 2014).

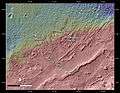

Close-up map - Aeolis Mons slopes - with few craters (bottom) (September 11, 2014). Geology map - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014).

Geology map - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014). Geology map - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014).

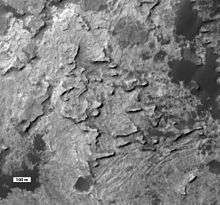

Geology map - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014). "Murray Buttes" knobs - Aeolis Mons slopes (November 13, 2013).[10]

"Murray Buttes" knobs - Aeolis Mons slopes (November 13, 2013).[10] "Murray Buttes" mesa - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014).

"Murray Buttes" mesa - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014). "Murray Formation" bands - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014).

"Murray Formation" bands - Aeolis Mons slopes (September 11, 2014). "Pahrump Hills" - Notable places at base of Aeolis Mons (Autumn, 2014).

"Pahrump Hills" - Notable places at base of Aeolis Mons (Autumn, 2014). "Pahrump Hills" sand - viewed by Curiosity (November 13, 2014).

"Pahrump Hills" sand - viewed by Curiosity (November 13, 2014). "Pahrump Hills" sand - Curiosity's tracks (November 7, 2014).

"Pahrump Hills" sand - Curiosity's tracks (November 7, 2014).

"Confidence Hills" rock on Mars - Curiosity's 1st target at Aeolis Mons (September 24, 2014).

"Confidence Hills" rock on Mars - Curiosity's 1st target at Aeolis Mons (September 24, 2014). "Pahrump Hills" bedrock on Mars - viewed by Curiosity (November 9, 2014).

"Pahrump Hills" bedrock on Mars - viewed by Curiosity (November 9, 2014). "Pink Cliffs" rock outcrop on Mars - viewed by Curiosity (October 7, 2014).

"Pink Cliffs" rock outcrop on Mars - viewed by Curiosity (October 7, 2014). "Alexander Hills" bedrock on Mars - viewed by Curiosity (November 23, 2014).

"Alexander Hills" bedrock on Mars - viewed by Curiosity (November 23, 2014). Ancient Lake fills Gale Crater on Mars (simulated view).

Ancient Lake fills Gale Crater on Mars (simulated view). Murray formation lakebeds with aeolian(?) erosional fins, October 9, 2016

Murray formation lakebeds with aeolian(?) erosional fins, October 9, 2016

(September 11, 2014).

(September 11, 2014; white balanced).

Images

Gale crater - surface materials (false colors; THEMIS; 2001 Mars Odyssey).

Gale crater - surface materials (false colors; THEMIS; 2001 Mars Odyssey). Gale crater with Aeolis Mons rising from the center. Curiosity's landing area (marked) is in Aeolis Palus.

Gale crater with Aeolis Mons rising from the center. Curiosity's landing area (marked) is in Aeolis Palus. Aeolis Mons rises from the middle of Gale - Green dot marks Curiosity's landing site in Aeolis Palus.

Aeolis Mons rises from the middle of Gale - Green dot marks Curiosity's landing site in Aeolis Palus. Gale crater with Curiosity's landing area within Aeolis Palus noted - north is down.

Gale crater with Curiosity's landing area within Aeolis Palus noted - north is down. Aeolis Mons may have formed from the erosion of sediment layers that once filled Gale.

Aeolis Mons may have formed from the erosion of sediment layers that once filled Gale. Curiosity's landing site (green dot) - blue dot marks Glenelg Intrigue - blue spot marks the base of Mount Sharp - a planned area of study.

Curiosity's landing site (green dot) - blue dot marks Glenelg Intrigue - blue spot marks the base of Mount Sharp - a planned area of study. Curiosity's landing site - "Quad Map" includes "Yellowknife" Quad 51 of Aeolis Palus in Gale.

Curiosity's landing site - "Quad Map" includes "Yellowknife" Quad 51 of Aeolis Palus in Gale. Curiosity's landing site - "Yellowknife" Quad 51 (1-mi-by-1-mi) of Aeolis Palus in Gale.

Curiosity's landing site - "Yellowknife" Quad 51 (1-mi-by-1-mi) of Aeolis Palus in Gale.

Comparison of color versions (raw, natural, white balance) of Aeolis Mons (August 23, 2012).

Comparison of color versions (raw, natural, white balance) of Aeolis Mons (August 23, 2012). Aeolis Mons as viewed by Curiosity (August 8, 2012) (white balanced image).

Aeolis Mons as viewed by Curiosity (August 8, 2012) (white balanced image). Layers at the base of Aeolis Mons - dark rock in inset is same size as Curiosity (white balanced image).

Layers at the base of Aeolis Mons - dark rock in inset is same size as Curiosity (white balanced image).

First-Year & First-Mile Traverse Map of the Curiosity rover on Mars (August 1, 2013) (3-D).

First-Year & First-Mile Traverse Map of the Curiosity rover on Mars (August 1, 2013) (3-D).

See also

References

- 1 2 3 ""Mount Sharp" on Mars Compared to Three Big Mountains on Earth". NASA. March 27, 2012. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ↑ Aeolis Mons

- ↑ NASA Staff (August 10, 2012). "Curiosity's Quad – IMAGE". NASA. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ↑ Agle, DC; Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (August 9, 2012). "NASA's Curiosity Beams Back a Color 360 of Gale Crate". NASA. Retrieved August 11, 2012.

- ↑ Amos, Jonathan (August 9, 2012). "Mars rover makes first colour panorama". BBC News. Retrieved August 9, 2012.

- ↑ Halvorson, Todd (August 9, 2012). "Quad 51: Name of Mars base evokes rich parallels on Earth". USA Today. Retrieved August 12, 2012.

- ↑ NASA Staff (August 6, 2012). "NASA Lands Car-Size Rover Beside Martian Mountain". NASA. Retrieved August 6, 2012.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne; Cole, Steve; Webster, Guy; Agle, D.C. (August 22, 2012). "NASA Mars Rover Begins Driving at Bradbury Landing". NASA. Retrieved August 22, 2012.

- ↑ NASA Staff (August 6, 2012). "NASA Lands Car-Size Rover Beside Martian Mountain". NASA/JPL. Retrieved August 7, 2012.

- 1 2 Webster, Guy; Brown, Dwayne (November 13, 2013). "Mars Rover Teams Dub Sites In Memory of Bruce Murray". NASA. Retrieved November 14, 2013.

- 1 2 Staff (June 5, 2013). "From 'Glenelg' to Mount Sharp". NASA. Retrieved June 6, 2013.

- 1 2 Chang, Alicia (June 5, 2013). "Curiosity rover to head toward Mars mountain soon". AP News. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Chang, Kenneth (June 7, 2013). "Martian Rock Another Clue to a Once Water-Rich Planet". New York Times. Retrieved June 7, 2013.

- 1 2 3 Webster, Guy; Agle, DC; Brown, Dwayne (September 11, 2014). "NASA's Mars Curiosity Rover Arrives at Martian Mountain". NASA. Retrieved September 10, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Chang, Kenneth (September 11, 2014). "After a Two-Year Trek, NASA's Mars Rover Reaches Its Mountain Lab". New York Times. Retrieved September 12, 2014.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (5 October 2015). "Mars Is Pretty Clean. Her Job at NASA Is to Keep It That Way.". New York Times. Retrieved 6 October 2015.

- 1 2 "Gale Crater's History Book". Mars Odyssey THEMIS web site. Arizona State University. Retrieved December 7, 2012. External link in

|work=(help) - 1 2 Anderson, R. B.; Bell III, J. F. (2010). "Geologic mapping and characterization of Gale Crater and implications for its potential as a Mars Science Laboratory landing site". International Journal of Mars Science and Exploration. 5: 76–128. Bibcode:2010IJMSE...5...76A. doi:10.1555/mars.2010.0004.

- ↑ Cabrol, N. A.; et al. (1999). "Hydrogeologic evolution of Gale Crater and its relevance in the exobiological exploration of Mars" (PDF). Icarus. 139 (2): 235–245. Bibcode:1999Icar..139..235C. doi:10.1006/icar.1999.6099.

- ↑ Irwin, R. P.; Howard, A. D.; Craddock, R. A.; Moore, J. M. (2005). "An intense terminal epoch of widespread fluvial activity on early Mars: 2. Increased runoff and paleolake development". Journal of Geophysical Research. 110: E12S15. Bibcode:2005JGRE..11012S15I. doi:10.1029/2005JE002460.

- ↑ Wall, M. (May 6, 2013). "Bizarre Mars Mountain Possibly Built by Wind, Not Water". Space.com. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Kite, E. S.; Lewis, K. W.; Lamb, M. P.; Newman, C. E.; Richardson, M. I. (2013). "Growth and form of the mound in Gale Crater, Mars: Slope wind enhanced erosion and transport". Geology. 41 (5): 543–546. doi:10.1130/G33909.1. ISSN 0091-7613.

- ↑ Brown, Dwayne; Webster, Guy (December 8, 2014). "Release 14-326 – NASA's Curiosity Rover Finds Clues to How Water Helped Shape Martian Landscape". NASA. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ Kaufmann, Marc (December 8, 2014). "(Stronger) Signs of Life on Mars". New York Times. Retrieved December 8, 2014.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (December 8, 2014). "Curiosity Rover's Quest for Clues on Mars". New York Times. Retrieved December 9, 2014.

- ↑ Clavin, Whitney (October 8, 2015). "NASA's Curiosity Rover Team Confirms Ancient Lakes on Mars". NASA. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ↑ Grotzinger, J.P.; et al. (October 9, 2015). "Deposition, exhumation, and paleoclimate of an ancient lake deposit, Gale crater, Mars". Science. 350 (6257): aac7575. doi:10.1126/science.aac7575. Retrieved October 9, 2015.

- ↑ Fred W. Price (1988). The Moon observer's handbook. London: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-33500-0.

- ↑ Mount Everest (1:50,000 scale map), prepared under the direction of Bradford Washburn for the Boston Museum of Science, the Swiss Foundation for Alpine Research, and the National Geographic Society, 1991, ISBN 3-85515-105-9

- ↑ "Kilimajaro Guide—Kilimanjaro 2010 Precise Height Measurement Expedition". Retrieved May 16, 2009.

- ↑ S. Green – Kilimanjaro: Highest Mountain in Africa – About.com

- ↑ Adam Helman, 2005. The Finest Peaks : Prominence and Other Mountain Measures, p. 9: "the base to peak rise of Mount McKinley is the largest of any mountain that lies entirely above sea level, some 18000 feet"

- ↑ Sumitpostorg – Zugspitze

- ↑ "Mont Blanc shrinks by 45cm in two years". Sydney Morning Herald. November 6, 2009.

- ↑ NASA – Layers in Lower Formation of Gale Crater Mound

- 1 2 "Mount Sharp or Aeolis Mons?". Sky & Telescope. August 14, 2012. Retrieved August 18, 2012.

- ↑ Space.com staff (March 29, 2012). "NASA's New Mars Rover Will Explore Towering "Mount Sharp"". Space.com. Retrieved March 30, 2012.

- 1 2 Blue, J. (May 16, 2012). "Three New Names Approved for Features on Mars". US Geological Survey. Retrieved May 28, 2012.

- ↑ Agle, D. C. (March 28, 2012). "'Mount Sharp' On Mars Links Geology's Past and Future". NASA. Retrieved March 31, 2012.

- ↑ ESA – Mars Express marks the spot for Curiosity landing

- ↑ Webster, Guy; Neal-Jones, Nancy; Brown, Dwayne (December 16, 2014). "NASA Rover Finds Active and Ancient Organic Chemistry on Mars". NASA. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Chang, Kenneth (December 16, 2014). "'A Great Moment': Rover Finds Clue That Mars May Harbor Life". New York Times. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Mahaffy, P.R.; et al. (December 16, 2014). "Mars Atmosphere – The imprint of atmospheric evolution in the D/H of Hesperian clay minerals on Mars". Science. 347: 412–414. Bibcode:2015Sci...347..412M. doi:10.1126/science.1260291. Retrieved December 16, 2014.

- ↑ Webster, Guy (August 6, 2013). "Mars Curiosity Landing: Relive the Excitement". NASA. Retrieved August 7, 2013.

- 1 2 Staff (August 27, 2013). "PIA17355: Curiosity's Progress on Route from 'Glenelg' to Mount Sharp". NASA. Retrieved November 20, 2013.

- ↑ Mars Science Laboratory: Multimedia-Images

Further reading

- Jürgen Blunck – Mars and its Satellites, A Detailed Commentary on the Nomenclature, 2nd edition. 1982.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aeolis Mons. |

| Look up Aeolis Mons in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Google Mars scrollable map – centered on Aeolis Mons.

- Aeolis Mons – Curiosity Rover "StreetView" (Sol 2 – 08/08/2012) – NASA/JPL – 360° Panorama

- Aeolis Mons – Curiosity Rover Mission Summary – Video (02:37)

- Aeolis Mons – HiRise (South side of mountain)

- Aeolis Mons – "Mount Sharp" Oblique (19,663px × 1,452px)

- Aeolis Mons – Gale crater – Image/THEMIS VIS 18m/px Mosaic (Zoomable) (small)

- Aeolis Mons – Gale crater – image/HRSCview

- Aeolis Mons – HRSCview (oblique view looking east)

- Aeolis Mons – 7,703px × 2,253px black & white panorama

- Aeolis Mons – Color Panorama by Damien Bouic

- Images – PIA16105 PIA16104

- Video (04:32) – Evidence: Water "Vigorously" Flowed On Mars – September, 2012