Guilford County, North Carolina

| Guilford County, North Carolina | ||

|---|---|---|

_1.jpg) Guilford County Courthouse in Greensboro | ||

| ||

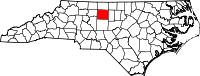

Location in the U.S. state of North Carolina | ||

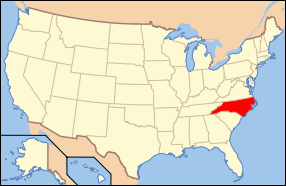

North Carolina's location in the U.S. | ||

| Founded | 1771 | |

| Named for | Francis North, 1st Earl of Guilford | |

| Seat | Greensboro | |

| Largest city | Greensboro | |

| Area | ||

| • Total | 658 sq mi (1,704 km2) | |

| • Land | 646 sq mi (1,673 km2) | |

| • Water | 12 sq mi (31 km2), 1.8% | |

| Population (est.) | ||

| • (2015) | 517,600 | |

| • Density | 792.7/sq mi (306/km²) | |

| Congressional districts | 6th, 12th | |

| Time zone | Eastern: UTC-5/-4 | |

| Website |

www | |

Guilford County is a county located in the U.S. state of North Carolina. As of the 2010 census, the population was 488,406,[1] making it the third-most populous county in North Carolina. Its seat is Greensboro.[2] Since 1938, an additional county court has been located in High Point, North Carolina. The county was formed in 1771.[3][4]

Guilford County is included in the Greensboro-High Point, NC Metropolitan Statistical Area, which is also included in the Greensboro-Winston-Salem-High Point, NC Combined Statistical Area.

History

At the time of European encounter, the inhabitants of the area that became Guilford County were a Siouan-speaking people called the Saura.[5] Beginning in the 1740s, settlers arrived in the region in search of fertile and affordable land. These first settlers included American Quakers from Pennsylvania, Maryland, and New England at what is now Greensboro,[6] as well as German Reformed and Lutherans in the east, British Quakers in the south and west, and Scotch-Irish Presbyterians in the center of today's Guilford County.[7] As population increased, the North Carolina colonial legislature organized the county in 1771, from parts of Rowan and Orange counties. It was named for Francis North, Earl of Guilford, father of Frederick North, Lord North, British Prime Minister from 1770 to 1782.[8]

Friedens Church, whose name means "peace" in German, is in eastern Guilford County, at 6001 NC Hwy 61 North, northwest of Gibsonville. It is a historic church established by some of the earliest European settlers in this area. According to a church history, Rev. John Ulrich Giesendanner led his Lutheran congregation from Pennsylvania in 1740 into the part of North Carolina around Haw River, Reedy Fork, Eno River, Alamance Creek, Travis Creek, Beaver Creek, and Deep River. Friedens Church built a log structure in 1745, which the congregation used for 25 years. The second building, completed about 1771, was more substantial and was used for a century, being replaced in May 1871. That third building was destroyed by fire on January 8, 1939, with only the front columns surviving destruction. The church was rebuilt and reopened in May 1939.[9]

The Quaker meeting also played a major role in the European settlement of the county. Numerous Quakers still live in the county. New Garden Friends Meeting, established in 1754 and first affiliated with a Pennsylvania meeting, still operates in Greensboro.

Alamance Presbyterian Church, a log structure, was built in 1762. The congregation was not officially organized until 1764 by the Rev. Henry Patillo, pastor of Hawfields Presbyterian Church. It has operated since then on the same site in present-day Greensboro. According to the church history, the congregation has built five churches on that site and now has its eighteenth pastor.[10]

On March 15, 1781, during the American Revolution, the Battle of Guilford Court House was fought just north of present-day Greensboro between Generals Charles Cornwallis and Nathanael Greene. This battle marked a turning point in the Revolutionary War in the South. Although General Cornwallis, the British Commander, held the field at the end of the battle, his losses were so severe that he decided to withdraw to the Carolina coastline, where he could receive reinforcements at Wilmington and his battered army could be protected by the British Navy. His decision ultimately led to his defeat later in 1781 at Yorktown, Virginia, by a combined force of American and French troops and warships.

In 1779 the southern third of Guilford County was separated as Randolph County. In 1785, following the American Revolution, the northern half of its remaining territory was organized as Rockingham County.

In 1808, Greensboro replaced the hamlet of Guilford Court House as the county seat. It was more centrally located, making it a better location for travelers of the time.

The county was the site of early industrial development, namely, the Mt. Hecla Cotton Mill, established in 1818 as one of the earliest cotton mills in the state. First run by water power, the mill was refitted to be powered by steam, and was one of the earliest examples in the state of the use of steam power for manufacturing. [11]

In the antebellum era, many of the county's residents were opposed to slavery, including Lutherans, Quakers and Methodists. The county was a stop on the Underground Railroad, for which volunteers aided refugee slaves en route to freedom in the North. People gave them safe places to stay and often food and clothing. Levi Coffin, among the founders of the "railroad," was a Guilford County native. He is credited with personally helping more than 2,000 slaves escape to freedom before the war.

Education has long been a hallmark of the county, which founded "first" among its institutions. Guilford College was founded in 1837 as the New Garden Boarding School; its name was changed in 1888 when the academic program was expanded considerably. Guilford is the third-oldest coeducational institution in the country and the oldest such institution in the South. Greensboro College, established by the Methodist Church through a charter secured in 1838, is one of the oldest institutions of higher education for women in the United States.

Immanuel Lutheran College and Seminary was located on a small campus on East Market Street until it closed in 1961. "Lutheran" was founded by white ethnic German Lutherans for black students in 1903 in Concord, at a time when education was racially segregated and blacks had limited access to higher education. The school moved to the county seat of Greensboro in 1905, where Lutherans built a large granite main building for it. The school operated a high school, junior college, and seminary under the jurisdiction of the Evangelical Lutheran Synodical Conference of North America.

In 1891, the county became home to the state's first and only publicly supported institution of higher learning for women, the State Normal and Industrial School, established in Greensboro especially to train teachers. In 1932, the school joined with the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and NC State University in Raleigh to form the Consolidated University of North Carolina; it was renamed as the Woman's College of the University of North Carolina. From the 1930s to the 1960s, the Woman's College was the third-largest women's university in the world. In 1963, the university was changed to a coed institution, and its curriculum was gradually expanded to include graduate work. It is now known as the University of North Carolina at Greensboro.

In 1911, a new county called Piedmont County was proposed, with High Point as its county seat, to be created from Guilford, Davidson and Randolph Counties. Many people appeared at the courthouse to oppose the plan, vowing to go to the state legislature to protest. The state legislature voted down the plan in February 1911.[12][13]

In 1960 North Carolina still operated by racial segregation laws, and maintained the disenfranchisement of most black voters established at the end of the 19th century to suppress the Republican Party. It operated mostly as a one-party state dominated by conservative white Democrats. Following World War II, African-American veterans and young people heightened their activities in the American civil rights movement. Guilford County was the site of an influential protest in 1960 when four black students from the North Carolina A&T State University in Greensboro started an early sit-in. Known afterwards as the Greensboro Four, the four young men sat at a "whites-only" lunch counter at the Woolworth's store in downtown Greensboro and asked to be served after purchasing items in the store. When refused, they asked why their money was good enough for buying retail items, but not food at the counter. They were arrested, but their action led to many other college students in Greensboro - including white students from Guilford and the Women's College - to sit at the lunch counter in a show of support. The students carried on a regular sit-in and within two months, the sit-in movement spread to 54 cities in nine states; Woolworth's eventually agreed to desegregate its lunch counters, and other restaurants in Southern towns and cities followed suit.

A darker racial incident in 1979 was called the Greensboro massacre. In this incident the predominantly African American Communist Workers Party (CWP) led a march protesting the Ku Klux Klan and other white-supremacist groups through a black neighborhood in southeastern Greensboro. They were attacked and shot at by KKK and American Nazi Party members; five of the Communist Party marchers were killed and seven wounded in the attack. In 1980 the case attracted renewed national attention when the six shooter defendants were found "not guilty" by an all-white jury. None of the people involved in this shooting, from either side, was a citizen of Guilford County; they simply chose the county seat of Greensboro as a rallying point. In 1985 families and friends of the victims won a civil case for damages against the city police department and other officials for failure to protect the African Americans; monies were paid to the Greensboro Justice Center.

Geography

According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the county has a total area of 658 square miles (1,700 km2), of which 646 square miles (1,670 km2) is land and 12 square miles (31 km2) (1.8%) is water.[14]

The county is drained, in part, by the Deep and Haw Rivers.

Adjacent counties

- Rockingham County (north)

- Alamance County (east)

- Randolph County (south)

- Davidson County (southwest)

- Forsyth County (west)

National protected area

Major highways

I‑40

I‑40 I‑40 Bus.

I‑40 Bus. I‑73

I‑73 I‑74

I‑74 I‑85

I‑85 I‑85 Bus.

I‑85 Bus. I‑785

I‑785 I‑840

I‑840 US 29

US 29 US 70

US 70 US 158

US 158 US 220

US 220 US 311

US 311 US 421

US 421 NC 22

NC 22 NC 61

NC 61 NC 62

NC 62 NC 65

NC 65 NC 68

NC 68 NC 100

NC 100 NC 150

NC 150

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 7,300 | — | |

| 1800 | 9,442 | 29.3% | |

| 1810 | 11,420 | 20.9% | |

| 1820 | 14,511 | 27.1% | |

| 1830 | 18,737 | 29.1% | |

| 1840 | 19,175 | 2.3% | |

| 1850 | 19,754 | 3.0% | |

| 1860 | 20,056 | 1.5% | |

| 1870 | 21,736 | 8.4% | |

| 1880 | 23,585 | 8.5% | |

| 1890 | 28,052 | 18.9% | |

| 1900 | 39,074 | 39.3% | |

| 1910 | 60,497 | 54.8% | |

| 1920 | 79,272 | 31.0% | |

| 1930 | 133,010 | 67.8% | |

| 1940 | 153,916 | 15.7% | |

| 1950 | 191,057 | 24.1% | |

| 1960 | 246,520 | 29.0% | |

| 1970 | 288,590 | 17.1% | |

| 1980 | 317,154 | 9.9% | |

| 1990 | 347,420 | 9.5% | |

| 2000 | 421,048 | 21.2% | |

| 2010 | 488,406 | 16.0% | |

| Est. 2015 | 517,600 | [15] | 6.0% |

| U.S. Decennial Census[16] 1790-1960[17] 1900-1990[18] 1990-2000[19] 2010-2013[1] | |||

As of the census of 2010,[1] there were 500,879 people, 192,064 households, 63% of which owned their own housing. The population density was 648 people per square mile (250/km²). There were 180,391 housing units at an average density of 278 per square mile (107/km²). The racial makeup of the county was 64.53% White, 29.27% Black or African American, 0.46% Native American, 2.44% Asian, 0.03% Pacific Islander, 1.81% from other races, and 1.45% from two or more races. 3.80% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 168,667 households out of which 30.40% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 48.00% were married couples living together, 13.40% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.90% were non-families. 27.90% of all households were made up of individuals and 8.30% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.41 and the average family size was 2.96.

In the county the population was spread out with 23.70% under the age of 18, 11.00% from 18 to 24, 31.40% from 25 to 44, 22.10% from 45 to 64, and 11.80% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 35 years. For every 100 females there were 92.00 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 88.60 males.

The median income for a household in the county was $42,618, and the median income for a family was $52,638. Males had a median income of $35,940 versus $27,092 for females. The per capita income for the county was $23,340. About 7.60% of families and 10.60% of the population were below the poverty line, including 13.80% of those under age 18 and 9.90% of those age 65 or over.

Law and government

Guilford County is a member of the regional Piedmont Triad Council of Governments.

Communities

Cities

- Archdale (part)

- Burlington (part)

- Greensboro (county seat)

- High Point (part)

Towns

Townships

- Bruce

- Center Grove

- Clay

- Deep River

- Fentress

- Friendship

- Gilmer

- Greene

- High Point

- Jamestown

- Jefferson

- Madison

- Monroe

- Morehead

- Oak Ridge

- Rock Creek

- Sumner

- Washington

Census-designated places

Unincorporated communities

Notable people

- Joseph Cannon, Speaker of the US House of Representatives (1903–1911)[20]

- Edward R. Murrow, American broadcast journalist

- Dolley Madison, wife of President James Madison and the fourth First Lady of the United States.

- William Sydney Porter, short-story writer better-known as "O. Henry"; his most famous story is "The Ransom of Red Chief".

- Levi Coffin, abolitionist leader who was nicknamed the "President of the Underground Railroad" for helping escaped slaves to freedom in the North before the Civil War.

See also

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Guilford County, North Carolina

- USS Guilford (APA-112)

References

- 1 2 3 "State & County QuickFacts". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved October 19, 2013.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- ↑ "North Carolina: Individual County Chronologies". North Carolina Atlas of Historical County Boundaries. The Newberry Library. 2009. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ↑ "Guilford County". NCpedia. State Library of North Carolina. January 1, 2006. Retrieved January 24, 2015.

- ↑ Ethel Stephens Arnett (1955). Greensboro, North Carolina: the county seat of Guilford. University of North Carolina Press. p. 7. Retrieved November 8, 2012.

- ↑ Hinshaw, William Wade, (Marshall, Thomas Worth, compiler) (1991) [1936]. "New Garden Monthly Meeting, Guilford County, NC". Encyclopedia of American Quaker Genealogy, vol. 1. Baltimore, MD: Genealogical Publishing Co. pp. 487–488. ISBN 0806301783.

- ↑ Bishir, Catherine (2005). North Carolina Architecture. UNC Press. p. 322.

- ↑ Gannett, Henry (1905). The Origin of Certain Place Names in the United States. Govt. Print. Off. p. 146.

- ↑ Apple, Lalah G. Two Hundred Twenty-Five Years History of Friedens Lutheran Church 1745 - 1970.

- ↑ "History of Alamance Presbyterian Church", official website. Accessed May 25, 2010

- ↑ Arnett, Ethel Stephens. Greensboro, North Carolina; the County Seat of Guilford. Chapel Hill: UNC Press, 1955. p. 166

- ↑ Jack Scism, "Remember When?", Greensboro News & Record, January 23, 2011.

- ↑ Jack Scism, "Remember When?", Greensboro News & Record, February 6, 2011.

- ↑ "2010 Census Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. August 22, 2012. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "County Totals Dataset: Population, Population Change and Estimated Components of Population Change: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2015". Retrieved July 2, 2016.

- ↑ "U.S. Decennial Census". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Historical Census Browser". University of Virginia Library. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ Forstall, Richard L., ed. (March 27, 1995). "Population of Counties by Decennial Census: 1900 to 1990". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "Census 2000 PHC-T-4. Ranking Tables for Counties: 1990 and 2000" (PDF). United States Census Bureau. April 2, 2001. Retrieved January 17, 2015.

- ↑ "CANNON, Joseph Gurney, (1836 - 1926)". Biographical Directory of the United States Congress. Retrieved November 26, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Guilford County, North Carolina. |

- Guilford County government official website

- NCGenWeb Guilford County - free genealogy resources for the county

|

Rockingham County |  | ||

| Forsyth County | |

Alamance County | ||

| ||||

| | ||||

| Davidson County | Randolph County |

Coordinates: 36°05′N 79°47′W / 36.08°N 79.79°W