Eigg

| Gaelic name | Eige |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | [ˈekʲə] |

| Norse name | Unknown |

| Meaning of name | Scottish Gaelic for 'notched island' (eag) |

An Sgurr | |

| Location | |

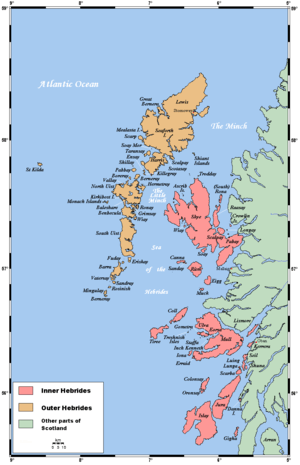

Eigg Eigg shown within Lochaber | |

| OS grid reference | NM476868 |

| Physical geography | |

| Island group | Small Isles |

| Area | 3,049 hectares (11.8 sq mi) |

| Area rank | 28 [1] |

| Highest elevation | An Sgurr 393 metres (1,289 ft) |

| Administration | |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Country | Scotland |

| Council area | Highland |

| Demographics | |

| Population | 83[2] |

| Population rank | 47 [1] |

| Pop. density | 2.7 people/km2[2][3] |

| Largest settlement | Cleadale |

| References | [3][4] |

Eigg (/ɛɡ/; Scottish Gaelic: Eige, [ˈekʲə]) is one of the Small Isles, in the Scottish Inner Hebrides. It lies to the south of the Skye and to the north of the Ardnamurchan peninsula. Eigg is 9 kilometres (5.6 mi) long from north to south, and 5 kilometres (3.1 mi) east to west. With an area of 12 square miles (31 km2), it is the second largest of the Small Isles after Rùm.

Notably, Eigg generates virtually 100% of its electricity using renewable energy.

Geography

The main settlement on Eigg is Cleadale, a fertile coastal plain in the north west. It is known for its quartz beach, called the "singing sands" (Tràigh a' Bhìgeil) on account of the squeaking noise it makes if walked on when dry.

The centre of the island is a moorland plateau, rising to 393 metres (1,289 ft) at An Sgurr, a dramatic stump of pitchstone, sheer on three sides. Walkers who complete the easy scramble to the top in good weather are rewarded with spectacular views all round of Mull, Coll, Muck, the Outer Hebrides, Rùm, Skye, and the mountains of Lochaber on the mainland.

Etymology

Adomnán calls the island Egea insula in his Vita Columbae (c. 700 AD). Other historical names have been Ega, Ego, Ege, Egge, Egg and Eige. A 2013 study suggested two origins: Gaelic eig, meaning "notch", or Norse egg or eggjar, meaning "a sharp edge on a mountain", as in Egge, Sogn og Fjordane.[5]

History

Bronze Age and Iron Age inhabitants have left their mark on Eigg. The monastery at Kildonan was founded by a missionary possibly from either Dal Riata or an Irish Kingdom, St. Donnan. He and his monks were massacred in 617 by the local Pictish queen. In medieval times the island was held by Clan Donald.

Writing in 1549, Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles wrote of "Egge" that it was: "gude mayne land with ane paroch kirk in it, with mony solenne geis; very gude for store, namelie for scheip, with ane heavin for heiland Galayis".[Note 1]

Massacre Cave

| Pronunciation | ||

|---|---|---|

| Scots Gaelic: | An Laimhrig | |

| Pronunciation: | [əˈlˠ̪ajvɾʲɪkʲ] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Clèadail | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈkʰliət̪al] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Eige | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈekʲə] | |

| Scots Gaelic: | Uamh Fhraing | |

| Pronunciation: | [ˈuəv ˈɾaŋʲkʲ] | |

During the sixteenth century there was a lengthy feud between the MacLeod and MacDonald clans, which may have led to the massacre of the island's entire population in the late 16th century. According to Clanranald tradition, in 1577 a party of MacLeods staying on the island became too amorous and caused trouble with the local girls. They were subsequently rounded up, bound and cast adrift in the Minch but were rescued by some clansmen. A party of MacLeods subsequently landed on Eigg with revenge in mind. Their approach had been spotted by the islanders who had hidden in a secret cave called the Cave of Frances (Scottish Gaelic: Uamh Fhraing) located on the south coast.[8] The entrance to this cave was tiny and covered by moss, undergrowth and a small waterfall. After a thorough but fruitless search lasting for three to five days, the MacLeods set sail again but a MacDonald carelessly climbed onto a promontory to watch their departure and was spotted. The MacLeods returned and were able to follow his footprints back to the cave. They then rerouted the source of the water, piled thatch and roof timbers at the cave entrance and set fire to it at the same time damping the flames so that the cave was filled with smoke thereby asphyxiating everyone inside either by smoke inhalation or heat and oxygen deprivation. Three hundred and ninety-five people died in the cave, the whole population of the island bar one old lady who had not sought refuge there. There are however some difficulties with this tale and in later times a minister of Eigg stated "the less I enquired into its history ... the more I was likely to feel I knew something about it."[9][10] Nonetheless, human remains in the cave were reported by Boswell in 1773, by Sir Walter Scott in 1814 and Hugh Miller in 1845. By 1854, they had been removed and buried elsewhere.[9][11]

Massacre Cave (grid reference NM474834) sits in the back of a fault-like crevice under a steep rock face. It is no more than 0.65 metres (2.1 ft) height and one needs to crawl to gain access and then keep crawling for a further 7 metres (23 ft) before it opens out. The length is approximately 79 metres (259 ft), the width 8 metres (26 ft) and height 6 metres (20 ft).

18th and 19th centuries

Near to Massacre Cave there is another tidal cave with a large and visible entrance; it is high-roofed and is said to have been used for Roman Catholic services after the Jacobite rising of 1745.

The Scottish geologist and writer Hugh Miller visited the island in the 1840s and wrote a long and detailed account of his explorations in his book The Cruise of the Betsey published in 1858. Miller was a self-taught geologist; so the book contains detailed observations of the geology of the island, including the Scuir and the singing sands. He describes the islanders of Eigg as "an active, middle-sized race, with well-developed heads, acute intellects, and singularly warm feelings". He describes seeing the bones of adults and children in family groups with the charred remains of their straw mattresses and small household objects still in Massacre Cave. Walter Scott was so appalled and moved on hearing that the skulls and bones of the dead were still stacked there, that he started a fund for a Christian burial, which resulted in their removal.

By the 19th century, the island had a population of 500, producing potatoes, oats, cattle and kelp. When sheep farming became more profitable than any alternative, land was cleared by compulsory emigration. One wave of emigrants in the 1820s settled on a high plateau along the Northumberland coast of Nova Scotia which they named Eigg Mountain. Later, in 1853, the whole of the village of Gruilin, fourteen families, was forced to leave.

Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust

After decades of problems with absentee landlords in the 20th century, the island was bought in 1997 by the Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust, a partnership between the residents of Eigg, the Highland Council, and the Scottish Wildlife Trust.[12] At the time, the usually resident population was around 65.[13] The island's population had grown to 83 as recorded by the 2011 census,[2] an increase of 24%. During the same period Scottish island populations as a whole grew by 4% to 103,702.[14] Many of the new residents are young people who have returned to the island or who have moved there to make it their home and set up in business.

The ceremony to mark the handover to community ownership took place a few weeks after the 1997 General Election and was attended by the Scottish Office Minister, Brian Wilson, a long-standing advocate of land reform. He used the occasion to announce the formation of a Community Land Unit within Highlands and Islands Enterprise that would in future support further land buy-outs in the region.

Lighthouse

Eilean Chathastail lighthouse viewed from the Mallaig-Eigg ferry. | |

| Location |

Eilean Chathastail Eigg Inner Hebrides Scotland United Kingdom |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 56°52′15″N 6°07′17″W / 56.870913°N 6.121394°W |

| Year first constructed | 1906 |

| Construction | metal tower |

| Tower shape | cylindrical tower with balcony and lantern |

| Markings / pattern | white tower and lantern |

| Height | 8 metres (26 ft) |

| Focal height | 24 metres (79 ft) |

| Light source | solar power |

| Characteristic | Fl W 6s. |

| Admiralty number | A4080 |

| NGA number | 4012 |

| ARLHS number | SCO-066 |

| Managing agent | Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust[15] |

Eigg lighthouse is an active lighthouse located on the islet of Eilean Chathastail, one of the Small Isles about 110 metres (360 ft) off Eigg. The lighthouse was built in 1906 on project by David A. and Charles Alexander Stevenson; it is a cylindrical metal tower 8 metres (26 ft) high with gallery and lantern painted white and is a minor light owned by Northern Lighthouse Board but managed by Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. The light emits a white flash every 6 seconds.

Economy and transport

Legend | |||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||

Tourism is important to the local economy, especially in the summer months, and the first major project of the Heritage Trust was An Laimhrig, a new building near the jetty to house the island's shop and post office, Galmisadale Bay restaurant and bar, a craft shop, and toilet and shower facilities, which are open 24 hours a day.[16] There are two ferry routes to the island. A'Nead Hand Knitwear is a new island business making garments such as cobweb shawls and scarves.[17]

There is a sheltered anchorage for boats at Galmisdale in the south of the island. In 2004 the old jetty there was extended to allow a roll-on roll-off ferry to dock. The Caledonian MacBrayne ferry Lochnevis sails a circular route from Mallaig around the four "Small Isles"—Eigg, Canna, Rùm and Muck from the fishing port of Mallaig. Arisaig Marine also runs a passenger ferry called the MV Sheerwater from April until late September from Arisaig on the mainland.[18]

Electrification project

The next major project of the Heritage Trust was to enable the provision of a mains electricity grid, powered from renewable sources. Previously, the island was not served by mains electricity and individual crofthouses had wind, hydro or diesel generators and the aim of the project is to develop an electricity supply that is environmentally and economically sustainable.

The new system incorporates a 9.9 kWp PV system, three hydro generation systems (totalling 112 kW) and a 24 kW wind farm supported by stand-by diesel generation and batteries to guarantee continuous availability of power. A load management system has been installed to provide optimal use of the renewables. This combination of solar, wind and hydro power should provide a network that is self-sufficient and powered 98% from renewable sources. The system was turned on 1 February 2008.[19] Eigg Electric generates a finite amount of energy and so Eigg residents agreed from the outset to cap electricity use at 5 kW at any one time for households, and 10 kW for businesses. If renewable resources are low, for example when there is less rain or wind, a "traffic light" system asks residents to keep their usage to a minimum. The traffic light reduces demand by up to 20% and ensures there's always enough energy for everyone.

The Heritage Trust has formed a company, Eigg Electric Ltd, to operate the new £1.6 million network, which has been part funded by the National Lottery and the Highlands and Islands Community Energy Company.[20][21]

Other sustainability projects

In September 2008, Eigg began a year-long series of projects as part of their success as one of ten finalists in NESTA's Big Green Challenge. While the challenge finished in September 2009, the work to make the island "green" is continuing with solar water panels, alternative fuels, mass domestic insulation, transport and local food all being tackled.[22] In May 2009, the island hosted the "Giant's Footstep Family Festival", which included talks, workshops, music, theatre and advice about what individuals and communities can do to tackle climate change.[23]

In January 2010, Eigg was announced as one of three joint winners in NESTA's Big Green Challenge, winning a prize of £300,000. Eigg also won the prestigious UK Gold Award in July 2010.

Wildlife

An average of 130 species of bird are recorded annually. The island has breeding populations of various raptors: golden eagle, buzzard, peregrine falcon, kestrel, hen harrier and short and long-eared owl. Great northern diver and jack snipe are winter visitors, and in summer cuckoo, whinchat, whitethroat and twite breed on the island.[24][25]

See also

- Religion of the Yellow Stick

- List of lighthouses in Scotland

- List of Northern Lighthouse Board lighthouses

- List of community buyouts in Scotland

References

- Notes

- Citations

- 1 2 Area and population ranks: there are c. 300 islands over 20 ha in extent and 93 permanently inhabited islands were listed in the 2011 census.

- 1 2 3 National Records of Scotland (15 August 2013) (pdf) Statistical Bulletin: 2011 Census: First Results on Population and Household Estimates for Scotland - Release 1C (Part Two). "Appendix 2: Population and households on Scotland’s inhabited islands". Retrieved 17 August 2013.

- 1 2 Haswell-Smith (2004) pp. 134–35

- ↑ Ordnance Survey. Get-a-map (Map). 1:25,000. Leisure. Ordinance Survey. Retrieved 21 August 2013.

- ↑ Broderick G., 2013, Some Island Names in the Former 'Kingdom of the Isles': A Reappraisal. The Journal of Scottish Name Studies 7:1-28. http://www.clanntuirc.co.uk/JSNS/V7/JSNS7%20Broderick.pdf

- ↑ Munro, D. (1818) Description of the Western Isles of Scotland called Hybrides, by Mr. Donald Munro, High Dean of the Isles, who travelled through most of them in the year 1549. Miscellanea Scotica, 2. Quoted in Banks (1977) p. 190

- ↑ Harvie-Brown, J. A. and Buckley, T. E. (1892), A Vertebrate Fauna of Argyll and the Inner Hebrides. Pub. David Douglas., Edinburgh. Facing P. LVI.

- ↑ Some sources translate the Gaelic Uamh Fhraing as the Cave of Francis. (Macpherson, Norman. Notes on antiquities from the island of Eigg, Edinburgh University.)

- 1 2 Banks (1977) pp. 56–67

- ↑ Kieran, Ben. Blood and Soil: A World History of Genocide and Extermination from Sparta to Darfur, Yale University Press, 2007 ISBN 0-300-10098-1, ISBN 978-0-300-10098-3. p. 14

- ↑ Lynn Forest-Hill, "Underground Man", Times Literary Supplement 14 January 2011 p. 15

- ↑ Alastair McIntosh (2001). Soil and Soul: People Versus Corporate Power. Aurum Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1854108029.

- ↑ General Register Office for Scotland (28 November 2003) Scotland's Census 2001 – Occasional Paper No 10: Statistics for Inhabited Islands. Retrieved 26 February 2012.

- ↑ "Scotland's 2011 census: Island living on the rise". BBC News. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 18 August 2013.

- ↑ Eigg The Lighthouse Directory. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Retrieved 22 May 2016

- ↑ "Eigg Shop and Post Office" Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "A'Nead Hand Knitwear" anead-knitwear.co.uk. Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ "Welcome to Arisaig Marine Ltd" arisaig.co.uk Retrieved 1 August 2009.

- ↑ Ross, John (31 January 2008). "Island finally turns on to green mains Eigg-tricity". The Scotsman. Retrieved 2 January 2015.

- ↑ "Isle of Eigg, Inner Hebrides, Scotland - 2007" Wind and Sun Ltd. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ "Island energised by lottery cash". BBC News. 16 November 2005. Retrieved 20 September 2007.

- ↑ "Green Eigg islanders earn place in UK's Big Challenge says Press and Journal" islandsgoinggreen.org. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ↑ "Take Giant Green Footsteps to Eigg's Family Festival". Senscot. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ↑ "Eigg-ceptional summer". Scottish Wildlife (November 2007) No. 63 page 4.

- ↑ "Bird watching on Eigg" Isle of Eigg Heritage Trust. Retrieved 27 December 2007.

- General references

- Banks, Noel, (1977) Six Inner Hebrides. Newton Abbott: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-7368-4

- Haswell-Smith, Hamish (2004). The Scottish Islands. Edinburgh: Canongate. ISBN 978-1-84195-454-7.

External links

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Eigg. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eigg. |

- The island's website

- Geology of Eigg

- BBC Radio 4 - Open Country

- BBC Action Network - My story: Bringing power to the people

- Ashden Awards Case Study, video and photographs

- Book about the role of incomers on the island and photogallery

- The Cruise of the Betsey- Account of Miller's voyage.

-

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Eigg". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Wood, James, ed. (1907). "Eigg". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. London and New York: Frederick Warne.

Coordinates: 56°54′N 6°10′W / 56.900°N 6.167°W