Albania

| Republic of Albania Republika e Shqipërisë |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: Ti Shqipëri, më jep nder, më jep emrin Shqipëtar You Albania, give me honour, give me the name Albanian |

||||||

| Anthem: Himni i Flamurit "Albanian National Anthem" |

||||||

![Location of Albania (green)in Europe (dark grey) – [Legend]](../I/m/Europe-Albania.svg.png) |

||||||

| Capital and largest city | Tirana 41°19′N 19°49′E / 41.317°N 19.817°E | |||||

| Official languages | Albanian | |||||

| Demonym | Albanian | |||||

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional republic | |||||

| • | President | Bujar Nishani | ||||

| • | Prime Minister | Edi Rama | ||||

| Legislature | Kuvendi | |||||

| Formation | ||||||

| • | Principality of Arbanon | 1190 | ||||

| • | Anjou Kingdom of Albania | February 1272 | ||||

| • | Princedom of Albania | 1368 | ||||

| • | League of Lezhë | 2 March 1444 | ||||

| • | Proclamation of independence from the Ottoman Empire | 28 November 1912 | ||||

| • | Principality of Albania (Recognised) | 29 July 1913 | ||||

| • | Albanian Republic (1st republic) | 31 January 1925 | ||||

| • | Albanian Kingdom | 1 September 1928 | ||||

| • | Under Italy Under Nazi Germany |

7 April 1939 29 November 1944 |

||||

| • | People's Republic of Albania (2nd republic) | 11 January 1946 | ||||

| • | People's Socialist Republic of Albania (3rd republic) | 28 December 1976 | ||||

| • | Republic of Albania (4th republic) Current constitution |

29 April 1991 28 November 1998 |

||||

| Area | ||||||

| • | Total | 28,748 km2 (143rd) 11,100 sq mi |

||||

| • | Water (%) | 4.7 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| • | 2016 estimate | 2,886,026[1] | ||||

| • | 2011 census | 2,821,977[2] | ||||

| • | Density | 98/km2 (63rd) 254/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $36.241 billion[3] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $12,582[3] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2017 estimate | |||||

| • | Total | $12.876 billion[3] | ||||

| • | Per capita | $4,470[3] | ||||

| Gini (2013) | 34.5[4] medium |

|||||

| HDI (2014) | high · 85th |

|||||

| Currency | Lek (ALL) | |||||

| Time zone | CET (UTC+1) | |||||

| • | Summer (DST) | CEST (UTC+2) | ||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | |||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Calling code | 355 | |||||

| ISO 3166 code | AL | |||||

| Internet TLD | .al | |||||

| a. | Aromanian, Greek, Macedonian and other regional languages are government-recognised minority languages. | |||||

Albania (![]() i/ælˈbeɪniə, ɔːl-/, a(w)l-BAY-nee-ə; Albanian: Shqipëri/Shqipëria; Gheg Albanian: Shqipni/Shqipnia, Shqypni/Shqypnia[6]), officially the Republic of Albania (Albanian: Republika e Shqipërisë, pronounced [ɾɛpuˈblika ɛ ʃcipəˈɾiːsə]), is a country in Southeast Europe, bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast,[lower-alpha 1] the Republic of Macedonia to the east, and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea to the west and on the Ionian Sea to the southwest. It is less than 72 km (45 mi) from Italy, across the Strait of Otranto which connects the Adriatic Sea to the Ionian Sea.

i/ælˈbeɪniə, ɔːl-/, a(w)l-BAY-nee-ə; Albanian: Shqipëri/Shqipëria; Gheg Albanian: Shqipni/Shqipnia, Shqypni/Shqypnia[6]), officially the Republic of Albania (Albanian: Republika e Shqipërisë, pronounced [ɾɛpuˈblika ɛ ʃcipəˈɾiːsə]), is a country in Southeast Europe, bordered by Montenegro to the northwest, Kosovo to the northeast,[lower-alpha 1] the Republic of Macedonia to the east, and Greece to the south and southeast. It has a coast on the Adriatic Sea to the west and on the Ionian Sea to the southwest. It is less than 72 km (45 mi) from Italy, across the Strait of Otranto which connects the Adriatic Sea to the Ionian Sea.

The present territory of Albania was part of the Roman provinces of Dalmatia, Macedonia and Moesia Superior. After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire in Europe following the Balkan Wars,[7] Albania declared independence in 1912 and was recognized the following year. The Kingdom of Albania was invaded by Italy in 1939, which formed Greater Albania, before becoming a Nazi German protectorate in 1943.[8] The following year, a socialist People's Republic was established under the leadership of Enver Hoxha and the Party of Labour. Albania experienced widespread social and political transformations in the communist era, as well as isolation from much of the international community. In 1991, the Socialist Republic was dissolved and the Republic of Albania was established.

Albania is a parliamentary republic. The country's capital, Tirana, is its financial and industrial heartland, with a population of about 800,000.[1][9] Free-market reforms have opened the country to foreign investment, especially in the development of energy and transportation infrastructure.[10][11][12] Albania has a high HDI and provides universal health care system and free primary and secondary education to its citizens.[5] Albania is an upper-middle income economy with the service sector dominating the country's economy, followed by the industrial sector and agriculture.[13]

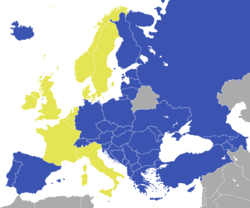

Albania is a member of the United Nations, NATO, the Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe, the Council of Europe, the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and the World Trade Organization. It is one of the founding members of the Energy Community, Organization of the Black Sea Economic Cooperation and the Union for the Mediterranean. It is also an official candidate for membership in the European Union.[14]

Etymology

Albania is the Medieval Latin name of the country. The country is called Shqipëri by its people. The name may be derived from the Illyrian tribe of the Albani recorded by Ptolemy, the geographer and astronomer from Alexandria who drafted a map in 150 AD that shows the city of Albanopolis located northeast of Durrës.[15][16]

The name may have a continuation in the name of a medieval settlement called Albanon and Arbanon, although it is not certain that this was the same place.[17] In his History written in 1079–1080, the Byzantine historian Michael Attaliates was the first to refer to Albanoi as having taken part in a revolt against Constantinople in 1043 and to the Arbanitai as subjects of the Duke of Dyrrachium.[18] During the Middle Ages, the Albanians called their country Arbëri or Arbëni and referred to themselves as Arbëresh or Arbënesh.[19][20]

As early as the 17th century the placename Shqipëria and the ethnic demonym Shqiptarë gradually replaced Arbëria and Arbëresh. The two terms are popularly interpreted as "Land of the Eagles" and "Children of the Eagles".[21][22]

History

The history of Albania emerged from the prehistoric stage from the 4th century BC, with early records of Illyria in Greco-Roman historiography.in

Prehistory

The first traces of human presence in Albania, dating to the Middle Paleolithic and Upper Paleolithic eras, were found in the village of Xarrë, near Sarandë and Mount Dajt near Tiranë.[23] The objects found in a cave near Xarrë include flint and jasper objects and fossilized animal bones, while those found at Mount Dajt comprise bone and stone tools similar to those of the Aurignacian culture. The Paleolithic finds of Albania show great similarities with objects of the same era found at Crvena Stijena in Montenegro and north-western Greece.[23]

Antiquity

In ancient times, the territory of modern Albania was mainly inhabited by a number of Illyrian tribes. This territory was known as Illyria, corresponding roughly to the area east of the Adriatic sea to the mouth of the Vjosë river in the south.[24][25] The first account of the Illyrian groups comes from Periplus of the Euxine Sea, an ancient Greek text written in the middle of the 4th century BC.[26] The south was inhabited by the Greek tribe of the Chaonians,[27] whose capital was at Phoenice, while numerous colonies, such as Apollonia, Epidamnos and Amantia, were established by Greek city-states on the coast by the 7th century BC.[28]

One of the most powerful tribes that ruled over modern Albania was the Ardiaei. The Ardiaen Kingdom reached its greatest extent under Agron, son of Pleuratus II. Agron extended his rule over other neighboring tribes as well.[29] After Agron's death in 230 BC, his wife Teuta inherited the Ardiaean kingdom. Teuta's forces extended their operations further southward into the Ionian Sea.[30] In 229 BC, Rome declared war[31] on Illyria for extensively plundering Roman ships. The war ended in Illyrian defeat in 227 BC. Teuta was eventually succeeded by Gentius in 181 BC.[32] Gentius clashed with the Romans in 168 BC, initiating the Third Illyrian War. The conflict resulted in Roman victory and the end of Illyrian independence by 167 BC. After his defeat, the Roman split the region into three administrative divisions.[33]

Middle Ages

The territory now known as Albania remained under Roman (Byzantine) control until the Slavs began to overrun it from 7th century,[34] and was captured by the Bulgarian Empire in the 9th century. After the weakening of the Byzantine Empire and the Bulgarian Empire in the middle and late 13th century, some of the territory of modern-day Albania was captured by the Serbian Principality. In general, the invaders destroyed or weakened Roman and Byzantine cultural centers in the lands that would become Albania.[35]

The territorial nucleus of the Albanian state formed in the Middle Ages, as the Principality of Arbër and the Kingdom of Albania. The Principality of Arbër or Albanon (Albanian: Arbër or Arbëria), was the first Albanian state during the Middle Ages, it was established by archon Progon in the region of Kruja, in c. 1190. Progon, the founder, was succeeded by his sons Gjin and Dhimitri, the latter which attained the height of the realm. After the death of Dhimiter, the last of the Progon family, the principality came under the Greek Gregory Kamonas[36][37] Lord or Prince (archon) of Krujë,[38] and later Golem. The Principality was dissolved in 1255.[39][40][41] Pipa and Repishti conclude that Arbanon was the first sketch of an "Albanian state", and that it retained semi-autonomous status as the western extremity of an empire (under the Doukai of Epirus or the Laskarids of Nicaea).[42] The Kingdom of Albania was established by Charles of Anjou in the Albanian territory he conquered from the Despotate of Epirus in 1271. He took the title of "King of Albania" in February 1272. The kingdom extended from the region of Durrës (then known as Dyrrhachium) south along the coast to Butrint. After the creation of the kingdom, a Catholic political structure was a good basis for the papal plans of spreading Catholicism in the Balkans. This plan found also the support of Helen of Anjou, a cousin of Charles of Anjou, who was at that time ruling territories in North Albania. Around 30 Catholic churches and monasteries were built during her rule in North Albania and in Serbia.[43] During 1331–55, the Serbian Empire wrestled control over Albania. After the dissolution of the Serbian Empire, several Albanian principalities were created, and among the most powerful were the Balsha, Thopia, Kastrioti, Muzaka and Arianiti. In the first half of the 14th century, the Ottoman Empire invaded most of Albania. But in 1444, the Albanian principalities were united under George Castrioti Skanderbeg, (Albanian: Gjergj Kastrioti, Skenderbeu) the national hero of Albania.

Ottoman Albania

.jpg)

At the dawn of the establishment of the Ottoman Empire in Southeast Europe, the geopolitical landscape was marked by scattered kingdoms of small principalities. The Ottomans erected their garrisons throughout southern Albania by 1415 and occupied most of Albania by 1431.[44] However, in 1443 a great and longstanding revolt broke out under the lead of the Albanian national hero Skanderbeg, which lasted until 1479, many times defeating major Ottoman armies led by the sultans Murad II and Mehmed II. Skanderbeg united initially the Albanian princes, and later on established a centralized authority over most of the non-conquered territories, becoming the ruling Lord of Albania. He also tried relentlessly but rather unsuccessfully to create a European coalition against the Ottomans. He thwarted every attempt by the Turks to regain Albania, which they envisioned as a springboard for the invasion of Italy and western Europe. His unequal fight against the mightiest power of the time won the esteem of Europe as well as some support in the form of money and military aid from Naples, the Papacy, Venice, and Ragusa.[45] With the arrival of the Turks, Islam was introduced in Albania as a third religion. This conversion caused a massive emigration of Albanians to the Christian European countries.[46] Along with the Bosniaks, Muslim Albanians occupied an outstanding position in the Ottoman Empire, and were the main pillars of Ottoman Porte's policy in the Balkans[47]

Enjoying this privileged position in the empire, Muslim Albanians held various high administrative positions, with over two dozen Grand Viziers of Albanian origin, such as Gen. Köprülü Mehmed Pasha, who commanded the Ottoman forces during the Ottoman-Persian Wars; Gen. Köprülü Fazıl Ahmed, who led the Ottoman armies during the Austro-Turkish War; and, later, Muhammad Ali Pasha of Egypt.[48]

In the 15th century, when the Ottomans were gaining a firm foothold in the region, Albanian towns were organised into four principal sanjaks. The government fostered trade by settling a sizeable Jewish colony of refugees fleeing persecution in Spain (at the end of the 15th century). Vlorë saw passing through its ports imported merchandise from Europe such as velvets, cotton goods, mohairs, carpets, spices and leather from Bursa and Constantinople.

Some citizens of Vlorë even had business associates throughout Europe.[48]

Albanians could also be found throughout the empire in Iraq, Egypt, Algeria and across the Maghreb, as vital military and administrative retainers.[50] This was partly due to the Devşirme system. The process of Islamization was an incremental one, commencing from the arrival of the Ottomans in the 14th century (to this day, a minority of Albanians are Catholic or Orthodox Christians, though the vast majority became Muslim). Timar holders, the bedrock of early Ottoman control in Southeast Europe, were not necessarily converts to Islam, and occasionally rebelled; the most famous of these rebels is Skanderbeg (his figure would rise up later on, in the 19th century, as a central component of the Albanian national identity). The most significant impact on the Albanians was the gradual Islamisation process of a large majority of the population, although it became widespread only in the 17th century.[47]

Mainly Catholics converted in the 17th century, while the Orthodox Albanians followed suit mainly in the following century. Initially confined to the main city centres of Elbasan and Shkoder, by this period the countryside was also embracing the new religion. The motives for conversion according to some scholars were diverse, depending on the context. The lack of source material does not help when investigating such issues.[47]

Albania remained under Ottoman control as part of the Rumelia province until 1912, when independent Albania was declared.

Era of nationalism and League of Prizren

The League of Prizren was formed on 1 June 1878, in Prizren, Kosovo Vilayet of Ottoman Empire. At first the Ottoman authorities supported the League of Prizren, whose initial position was based on the religious solidarity of Muslim landlords and people connected with the Ottoman administration. The Ottomans favoured and protected Muslim solidarity, and called for defense of Muslim lands, including present-day Bosnia and Herzegovina. This was the reason for naming the league The Committee of the Real Muslims (Albanian: Komiteti i Myslimanëve të Vërtetë).[51] The League issued a decree known as Kararname. Its text contained a proclamation that the people from "northern Albania, Epirus and Bosnia" are willing to defend the "territorial integrity" of the Ottoman Empire "by all possible means" against the troops of the Bulgaria, Serbia and Montenegro. It was signed by 47 Muslim deputies of the League on 18 June 1878.[52] Around 300 Muslims participated in the assembly, including delegates from Bosnia and mutasarrif (sanjakbey) of the Sanjak of Prizren as representatives of the central authorities, and no delegates from Scutari Vilayet.[53]

The Ottomans cancelled their support when the League, under the influence of Abdyl bey Frashëri, became focused on working toward Albanian autonomy and requested merging of four Ottoman vilayets (Kosovo, Scutari, Monastir and Ioannina) into a new vilayet of the Ottoman Empire (the Albanian Vilayet). The League used military force to prevent the annexing areas of Plav and Gusinje assigned to Montenegro by the Congress of Berlin. After several successful battles with Montenegrin troops such as in Novsice, under the pressure of the great powers, the League of Prizren was forced to retreat from their contested regions of Plav and Gusinje and later on, the league was defeated by the Ottoman army sent by the Sultan.[54] The Albanian uprising of 1912, the Ottoman defeat in the Balkan Wars and the advance of Montenegrin, Serbian and Greek forces into territories claimed as Albanian, led to the proclamation of independence by Ismail Qemali in Vlora, on 28 November 1912.

Independence

At the All-Albanian Congress in Vlorë on 28 November 1912[55] Congress participants constituted the Assembly of Vlorë.[56] The assembly of eighty-three leaders meeting in Vlorë in November 1912 declared Albania an independent country and set up a provisional government. The Provisional Government of Albania was established on the second session of the assembly held on 4 December 1912. It was a government of ten members, led by Ismail Qemali until his resignation on 22 January 1914.[57] The Assembly also established the Senate (Albanian: Pleqësi) with an advisory role to the government, consisting of 18 members of the Assembly.[58]

Albania's independence was recognized by the Conference of London on 29 July 1913, but the drawing of the borders of the newly established Principality of Albania ignored the demographic realities of the time. The International Commission of Control was established on 15 October 1913 to take care of the administration of newly established Albania until its own political institutions were in order.[59] Its headquarters were in Vlorë.[60] The International Gendarmerie was established as the first law enforcement agency of the Principality of Albania. At the beginning of November the first gendarmerie members arrived in Albania. Wilhelm of Wied was selected as the first prince.[61]

In November 1913 the Albanian pro-Ottoman forces had offered the throne of Albania to the Ottoman war minister of Albanian origin, Izzet Pasha.[62] The pro-Ottoman peasants believed that the new regime of the Principality of Albania was a tool of the six Christian Great Powers and local landowners that owned half of the arable land.[63]

On 28 February 1914, the Autonomous Republic of Northern Epirus was proclaimed in Gjirokastër by the local Greek population against incorporation to Albania. This initiative was short lived and in 1921 the southern provinces were finally incorporated to the Albanian Principality.[64][65] Meanwhile, the revolt of Albanian peasants against the new Albanian regime erupted under the leadership of the group of Muslim clerics gathered around Essad Pasha Toptani, who proclaimed himself the savior of Albania and Islam.[66][67] In order to gain support of the Mirdita Catholic volunteers from the northern mountains, Prince of Wied appointed their leader, Prênk Bibë Doda, to be the foreign minister of the Principality of Albania. In May and June 1914 the International Gendarmerie joined by Isa Boletini and his men, mostly from Kosovo,[68] and northern Mirdita Catholics were defeated by the rebels who captured most of Central Albania by the end of August 1914.[69] The regime of Prince of Wied collapsed and he left the country on 3 September 1914.[70]

Republic and monarchy

The short-lived principality (1914–1925) was succeeded by the first Albanian Republic (1925–1928). In 1925 the four-member Regency was abolished and Ahmed Zogu was elected president of the newly declared republic. Tirana was endorsed officially as the country's permanent capital.[71] Zogu led an authoritarian and conservative regime, the primary aim of which was the maintenance of stability and order. Zogu was forced to adopt a policy of cooperation with Italy. A pact had been signed between Italy and Albania on 20 January 1925 whereby Italy gained a monopoly on shipping and trade concessions.[72]

The Albanian republic was eventually replaced by another monarchy in 1928. In order to extend his direct control throughout the entire country, Zogu placed great emphasis on the construction of roads. Every male Albanian over the age of 16 years was legally bound to give ten days of free labor each year to the state.[72] King Zogu remained a conservative, but initiated reforms. For example, in an attempt at social modernization, the custom of adding one's region to one's name was dropped. Zogu also made donations of land to international organisations for the building of schools and hospitals. The armed forces were trained and supervised by Italian instructors. As a counterweight, Zogu kept British officers in the Gendarmerie despite strong Italian pressure to remove them. The kingdom was supported by the fascist regime in Italy and the two countries maintained close relations until Italy's sudden invasion of the country in 1939. Albania was occupied by Fascist Italy and then by Nazi Germany during World War II.

World War II

After being militarily occupied by Italy, from 1939 until 1943 the Albanian Kingdom was a protectorate and a dependency of Italy governed by the Italian King Victor Emmanuel III and his government. After the Axis' invasion of Yugoslavia in April 1941, territories of Yugoslavia with substantial Albanian population were annexed to Albania: most of Kosovo,[lower-alpha 1] as well as Western Macedonia, the town of Tutin in Central Serbia and a strip of Eastern Montenegro.[73] In November 1941, the small Albanian Communist groups established an Albanian Communist Party in Tirana of 130 members under the leadership of Enver Hoxha and an eleven-man Central Committee. The party at first had little mass appeal, and even its youth organization netted few recruits.

After the capitulation of Italy in 1943, Nazi Germany occupied Albania too. The nationalist Balli Kombetar, which had fought against Italy, formed a "neutral" government in Tirana, and side by side with the Germans fought against the communist-led National Liberation Movement of Albania.[74] The Center for Relief to Civilian Populations (Geneva) reported that Albania was one of the most devastated countries in Europe. 60,000 houses were destroyed and about 10% of the population was left homeless.The communist partisans had regrouped and gained control of much of southern Albania in January 1944. However, they were subject to German attacks driving them out of certain areas. In the Congress of Përmet, the NLF formed an Anti-Fascist Council of National Liberation to act as Albania's administration and legislature. By the last year in World War II Albania fell into a civil war-like state between the communists and nationalists. The communist partisans however defeated the last Balli Kombëtar forces in southern Albania by mid-summer 1944. Before the end of November, the main German troops had withdrawn from Tirana, and the communists took control by attacking it. The partisans entirely liberated Albania from German occupation on 29 November 1944. A provisional government, which the communists had formed at Berat in October, administered Albania with Enver Hoxha as prime minister.

Communist Albania

By the end of World War II, the main military and political force in the country, the Communist party, sent forces to northern Albania against the nationalists to eliminate its rivals. They faced open resistance in Nikaj-Mertur, Dukagjin and Kelmend (Kelmendi was led by Prek Cali).[75] On 15 January 1945, a clash took place between partisans of the first Brigade and nationalist forces at the Tamara Bridge, resulting in the defeat of the nationalist forces. About 150 Kelmendi[76] people were killed or tortured. This event was the starting point of many other issues which took place during Enver Hoxha's dictatorship. Class struggle was strictly applied, human freedom and human rights were denied.[77] The Kelmend region was isolated by both the border and by a lack of roads for another 20 years, the institution of agricultural cooperatives brought about economic decline. Many Kelmendi people fled, some were executed trying to cross the border.[77]

After the liberation of Albania from Nazi occupation, the country became a Communist state, the People's Republic of Albania (renamed "the People's Socialist Republic of Albania" in 1976), which was led by Enver Hoxha and the Labour Party of Albania.[78]

The socialist reconstruction of Albania was launched immediately after the annulling of the monarchy and the establishment of a "People's Republic". In 1947, Albania's first railway line was completed, with the second one being completed eight months later. New land reform laws were passed granting ownership of the land to the workers and peasants who tilled it. Agriculture became cooperative, and production increased significantly, leading to Albania's becoming agriculturally self-sufficient. By 1955, illiteracy was eliminated among Albania's adult population.[79]

During this period Albania became industrialized and saw rapid economic growth, as well as unprecedented progress in the areas of education and health.[77] The average annual rate of Albania's national income was 29% higher than the world average and 56% higher than the European average.[81] Albania's Communist constitution did not allow taxes on individuals; instead, taxes were imposed on cooperatives and other organizations, with much the same effect.[82]

Religious freedoms were severely curtailed during the Communist period, with all forms of worship being outlawed. In August 1945, the Agrarian Reform Law meant that large swaths of property owned by religious groups (mostly Islamic waqfs) were nationalized, along with the estates of monasteries and dioceses. Many believers, along with the ulema and many priests, were arrested and executed. In 1949, a new Decree on Religious Communities required that all their activities be sanctioned by the state alone.[83]

In 1967, after hundreds of mosques and dozens of Islamic libraries containing priceless manuscripts were destroyed, Hoxha proclaimed Albania the "world's first atheist state".[84][85] The country's churches had not been spared either, and many were converted into cultural centers for young people. A 1967 law banned all "fascist, religious, warmongerish, antisocialist activity and propaganda." Preaching religion carried a three to ten-year prison sentence. Nonetheless, many Albanians continued to practice their beliefs secretly. The Hoxha dictatorship's anti-religious crusade attained its most fundamental legal and political expression a decade later: "The state recognizes no religion," declared Communist Albania's 1976 constitution, "and supports and carries out atheistic propaganda in order to implant a scientific materialistic world outlook in people."[85]

Hoxha's political successor Ramiz Alia oversaw the dismemberment of the "Hoxhaist" state during the breakup of the Eastern Bloc in the later 1980s.

Post-Communist Albania

After protests beginning in 1989 and reforms made by the communist government in 1990, the People's Republic was dissolved in 1991–92 and the Republic of Albania was founded. The communists retained a stronghold in parliament after popular support in the elections of 1991. However, in March 1992, amid liberalization policies resulting in economic collapse and social unrest, a new front led by the new Democratic Party took power.

In the following years, much of the accumulated wealth of the country was invested in Ponzi pyramid banking schemes, which were widely supported by government officials. The schemes swept up somewhere between one-sixth to one-third of the country's population.[86][87] Despite IMF warnings in late 1996, then president Sali Berisha defended the schemes as large investment firms, leading more people to redirect their remittances and sell their homes and cattle for cash to deposit in the schemes.[88] The schemes began to collapse in late 1996, leading many of the investors into initially peaceful protests against the government, requesting their money back. The protests turned violent in February as government forces responded with fire. In March the police and Republican Guard deserted, leaving their armories open. They were promptly emptied by militias and criminal gangs. The resulting crisis caused a wave of evacuations of foreign nationals and of refugees.[89]

The crisis led Prime Minister Aleksandër Meksi to resign on 11 March 1997, followed by President Sali Berisha in July in the wake of the June General Election. In April 1997, Operation Alba, a UN peacekeeping force led by Italy, entered the country with two goals: assistance in evacuation of expatriates and to secure the ground for international organizations. This was primarily WEU MAPE, who worked with the government in restructuring the judicial system and police. The Socialist Party won the elections in 1997, and a degree of political stabilization followed.

In 1999, the country was affected by the Kosovo War, when a great number of Albanians from Kosovo found refuge in Albania.

Albania became a full member of NATO in 2009, and has applied to join the European Union. In 2013, the Socialist Party won the national elections. In June 2014, the Republic of Albania became an official candidate for accession to the European Union.

Geography

Albania has a total area of 28,748 square kilometres (11,100 square miles). It lies between latitudes 42° and 39° N (Vermosh-Konispol) and between longitudes 21° and 19° E (Sazan-Vernik). Albania's coastline length is 476 km (296 mi)[90]:240 and extends along the Adriatic and Ionian Seas. The lowlands of the west face the Adriatic Sea.

The 70% of the country that is mountainous is rugged and often inaccessible from the outside. The highest mountain is Korab situated in the former district of Dibër, reaching up to 2,764 metres (9,068 ft). The climate on the coast is typically Mediterranean with mild, wet winters and warm, sunny, and rather dry summers.

Inland conditions vary depending on elevation, but the higher areas above 1,500 m/5,000 ft are rather cold and frequently snowy in winter; here cold conditions with snow may linger into spring. Besides the capital city of Tirana, which has 420,000 inhabitants, the principal cities are Durrës, Korçë, Elbasan, Shkodër, Gjirokastër, Vlorë and Kukës. In Albanian grammar, a word can have indefinite and definite forms, and this also applies to city names: both Tiranë and Tirana, Shkodër and Shkodra are used.

The three largest and deepest tectonic lakes of the Balkan Peninsula are partly located in Albania. Lake Shkodër in the country's northwest has a surface which can vary between 370 km2 (140 sq mi) and 530 km2, out of which one third belongs to Albania and the rest to Montenegro. The Albanian shoreline of the lake is 57 km (35 mi). Ohrid Lake is situated in the country's southeast and is shared between Albania and Republic of Macedonia. It has a maximal depth of 289 meters and a variety of unique flora and fauna can be found there, including "living fossils" and many endemic species. Because of its natural and historical value, Ohrid Lake is under the protection of UNESCO. There is also Lake Butrint which is a small tectonic lake. It is located in the National Park of Butrint.

-

View of the Valbonë Valley National Park

-

The Lake of Shkodër is the largest lake in Southern Europe.

Climate

With its coastline facing the Adriatic and Ionian seas, its highlands backed upon the elevated Balkan landmass, and the entire country lying at a latitude subject to a variety of weather patterns during the winter and summer seasons, Albania has a high number of climatic regions relative to its landmass. The coastal lowlands have typically Mediterranean climate; the highlands have a Mediterranean continental climate. In both the lowlands and the interior, the weather varies markedly from north to south.

The lowlands have mild winters, averaging about 7 °C (45 °F). Summer temperatures average 24 °C (75 °F). In the southern lowlands, temperatures average about 5 °C (9 °F) higher throughout the year. The difference is greater than 5 °C (9 °F) during the summer and somewhat less during the winter.

Inland temperatures are affected more by differences in elevation than by latitude or any other factor. Low winter temperatures in the mountains are caused by the continental air mass that dominates the weather in Eastern Europe. Northerly and northeasterly winds blow much of the time. Average summer temperatures are lower than in the coastal areas and much lower at higher elevations, but daily fluctuations are greater. Daytime maximum temperatures in the interior basins and river valleys are very high, but the nights are almost always cool.

Average precipitation is heavy, a result of the convergence of the prevailing airflow from the Mediterranean Sea and the continental air mass. Because they usually meet at the point where the terrain rises, the heaviest rain falls in the central uplands. Vertical currents initiated when the Mediterranean air is uplifted also cause frequent thunderstorms. Many of these storms are accompanied by high local winds and torrential downpours.

When the continental air mass is weak, Mediterranean winds drop their moisture farther inland. When there is a dominant continental air mass, cold air spills onto the lowland areas, which occurs most frequently in the winter. Because the season's lower temperatures damage olive trees and citrus fruits, groves and orchards are restricted to sheltered places with southern and western exposures, even in areas with high average winter temperatures.

Lowland rainfall averages from 1,000 millimeters (39.4 in) to more than 1,500 millimeters (59.1 in) annually, with the higher levels in the north. Nearly 95% of the rain falls in the winter.

Rainfall in the upland mountain ranges is heavier. Adequate records are not available, and estimates vary widely, but annual averages are probably about 1,800 millimeters (70.9 in) and are as high as 2,550 millimeters (100.4 in) in some northern areas. The western Albanian Alps (valley of Boga) are among the wettest areas in Europe, receiving some 3,100 mm (122.0 in) of rain annually.[91] The seasonal variation is not quite as great in the coastal area.

The higher inland mountains receive less precipitation than the intermediate uplands. Terrain differences cause wide local variations, but the seasonal distribution is the most consistent of any area.

-

Mediterranean climate in Bokërrimat e Muzinës

-

Subtropical climate in James Lake

In 2009, an expedition from University of Colorado discovered four small glaciers in the "Cursed" mountains in North Albania. The glaciers are at the relatively low level of 2,000 metres (6,600 ft), almost unique for such a southerly latitude.[92]

Flora and Fauna

Although a small country, Albania is distinguished for its rich biological diversity. The variation of geomorphology, climate and terrain create favorable conditions for a number of endemic and sub-endemic species with 27 endemic and 160 subendemic vascular plants present in the country. The total number of plants is over 3250 species, approximately 30% of the entire flora species found in Europe.

Over a third of the territory of Albania – about 10,000 square kilometres (3,861 square miles);– is forested and the country is very rich in flora. About 3,000 different species of plants grow in Albania, many of which are used for medicinal purposes. Phytogeographically, Albania belongs to the Boreal Kingdom, the Mediterranean Region and the Illyrian province of the Circumboreal Region. Coastal regions and lowlands have typical Mediterranean macchia vegetation, whereas oak forests and vegetation are found on higher elevations. Vast forests of black pine, beech and fir are found on higher mountains and alpine grasslands grow at elevations above 1800 meters.[94]

According to the World Wide Fund for Nature and Digital Map of European Ecological Regions by the European Environment Agency, the territory of Albania can be subdivided into three ecoregions: the Illyrian deciduous forests, Pindus Mountains mixed forests and Dinaric Alpine mixed forests. The forests are home to a wide range of mammals, including wolves, bears, wild boars and chamois. Lynx, wildcats, pine martens and polecats are rare, but survive in some parts of the country.

There are around 760 vertebrate species found so far in Albania. Among these there are over 350 bird species, 330 freshwater and marine fish and 80 mammal species. There are some 91 globally threatened species found within the country, among which the Dalmatian pelican, pygmy cormorant, and the European sea sturgeon. Rocky coastal regions in the south provide good habitats for the endangered Mediterranean monk seal.

Some of the most significant bird species found in the country include the golden eagle – known as the national symbol of Albania[95] – vulture species, capercaillie and numerous waterfowl. The Albanian forests still maintain significant communities of large mammals such as the brown bear, gray wolf, chamois and wild boar.[94] The north and eastern mountains of the country are home to the last remaining Balkan lynx – a critically endangered population of the Eurasian lynx.[96]

Demographics

According to the 2011 Census results, the total population of Albania is 2,821,977 with a low Fertility rate of 1.49 children born per woman.[97][98] The fall of the Communist regime in 1990 Albania was accompanied with massive migration. External migration was prohibited outright in Communist Albania while internal migration was quite limited, hence this was a new phenomenon. Between 1991 and 2004, roughly 900,000 people have migrated out of Albania, about 600,000 of them settling in Greece.[99] Migration greatly affected Albania's internal population distribution. Population decreased mainly in the North and South of the country while it increased in Tirana and Durrës center districts. According to the Albanian Institute of Statistics, the population of Albania is 2,893,005 as of 1 January 2015.[1]

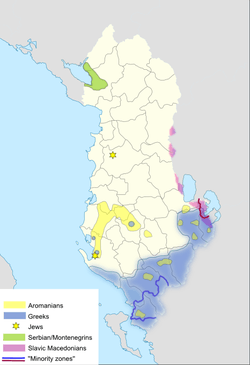

Issues of ethnicity are a delicate topic and subject to debate. "Although official statistics have suggested that Albania is one of the most homogenous countries in the region (with an over 97 per cent Albanian majority) minority groups (such as Greeks, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Roma and Vlachs/Aromanians) have often questioned the official data, claiming a larger share in the country's population.

"[100] The last census that contained ethnographic data (before the 2011 one) was conducted in 1989.[101]

Albania recognizes three national minorities, Greeks, Macedonians and Montenegrins, and two cultural minorities, Aromanians and Romani people.[102] Other Albanian minorities are Bulgarians, Gorani, Serbs, Balkan Egyptians, Bosniaks and Jews. Regarding the Greeks, "it is difficult to know how many Greeks there are in Albania. The Greek government, it is typically claimed, says that there are around 300,000 ethnic Greeks in Albania, but most western estimates are around 200,000 mark (although EEN puts the number at a probable 100,000)."[103][104][105][106][107] The Albanian government puts the number at only 24,243."[108] The CIA World Factbook estimates the Greek minority at 0.9%[109] of the total population and the US State Department uses 1.17% for Greeks and 0.23% for other minorities.[110] However, the latter questions the validity of the data about the Greek minority, due to the fact that measurements have been affected by boycott.[111]

According to the 2011 census the population of Albania declared the following ethnic affiliation: Albanians 2,312,356 (82.6% of the total), Greeks 24,243 (0.9%), Macedonians 5,512 (0.2%), Montenegrins 366 (0.01%), Aromanians 8,266 (0.30%), Romani 8,301 (0.3%), Balkan Egyptians 3,368 (0.1%), other ethnicities 2,644 (0.1%), no declared ethnicity 390,938 (14.0%), and not relevant 44,144 (1.6%).[2]

Macedonian and some Greek minority groups have sharply criticized Article 20 of the Census law, according to which a $1,000 fine will be imposed on anyone who will declare an ethnicity other than what is stated on his or her birth certificate. This is claimed to be an attempt to intimidate minorities into declaring Albanian ethnicity, according to them the Albanian government has stated that it will jail anyone who does not participate in the census or refuse to declare his or her ethnicity.[112] Genc Pollo, the minister in charge has declared that: "Albanian citizens will be able to freely express their ethnic and religious affiliation and mother tongue. However, they are not forced to answer these sensitive questions".[113] The amendments criticized do not include jailing or forced declaration of ethnicity or religion; only a fine is envisioned which can be overthrown by court.[114][115]

Greek representatives form part of the Albanian parliament and the government has invited Albanian Greeks to register, as the only way to improve their status.[100] On the other hand, nationalists, various intellectuals organizations and political parties in Albania have expressed their concern that the census might artificially increase the number of Greek minority, which might be then exploited by Greece to threaten Albania's territorial integrity.[100][116][117][118][119][120][121]

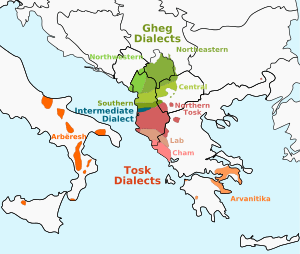

Language

Albanian is the official language of Albania. Its standard spoken and written form is revised and merged from the two main dialects, Gheg and Tosk, though it is notably based more on the Tosk dialect. Shkumbin river is the rough dividing line between the two dialects. Also a dialect of Greek that preserves features now lost in standard modern Greek is spoken in areas inhabited by the Greek minority. Other languages spoken by ethnic minorities in Albania include Vlach, Serbian, Macedonian, Bosnian, Bulgarian, Gorani, and Roma.[122] Macedonian is official in the Pustec Municipality in East Albania.

Albanians are considered a polyglot nation and people. Due to immigration and past colonialism, Albanians generally speak more than 2 languages. English, Italian and Greek are by far the most widely spoken foreign languages, which are increasing due to migration return, and new Greek and Italian communities in the country. La Francophonie states 320,000 French speakers can be found in Albania. Other spoken languages include Serbian, Romanian, German, Turkish and Aromanian. Albanians in neighbouring Kosovo and Macedonia are often fluent in Albanian and Serbian, Turkish, Slavic Macedonian, and other former Yugoslav languages.

According to the 2011 population census, 2,765,610 or 98.767% of the population declared Albanian as their mother tongue ("mother tongue is defined as the first or main language spoken at home during childhood").[2]

Religion

According to the 2011 census, 58.79% of Albania adheres to Islam, making it the largest religion in the country; Christianity is practiced by 17.06% of the population, and 24.29% of the total population is either non-religious, belongs to other religious groups, or are 'undeclared'.[123] Both the Albanian Orthodox church and the Bektashi Sufi order refused to recognize the 2011 census results regarding faith, with the Orthodox claiming that 24% of the total population are Albanian Orthodox Christians rather than just 6.75%.[124] Before World War II, 70% of the population were Muslims, 20% Eastern Orthodox, and 10% Roman Catholics.[7] According to a 2010 survey, religion today plays an important role in the lives of only 39% of Albanians, and Albania is ranked among the least religious countries in the world.[125] A 2012 Pew Research Center study found that 65% of Albanian Muslims are non-denominational Muslims.[126]

The Albanians first appeared in the historical record in Byzantine sources of the late 11th century. At this point, they were already fully Christianized. Islam came for the first time in the 9th century to the region which is known as Albania today.[127] It later emerged as the majority religion during the centuries of Ottoman rule, though a significant Christian minority remained. After independence (1912) from the Ottoman Empire, the Albanian republican, monarchic and later Communist regimes followed a systematic policy of separating religion from official functions and cultural life. Albania never had an official state religion either as a republic or as a kingdom. In the 20th century, the clergy of all faiths was weakened under the monarchy, and ultimately eradicated during the 1950s and 1960s, under the state policy of obliterating all organized religion from Albanian territories.

The Communist regime that took control of Albania after World War II persecuted and suppressed religious observance and institutions and entirely banned religion to the point where Albania was officially declared to be the world's first atheist state. Religious freedom has returned to Albania since the regime's change in 1992. Albania joined the Organisation of the Islamic Conference in 1992, following the fall of the communist government, but will not be attending the 2014 conference due a dispute regarding the fact that its parliament never ratified the country's membership.[128] Albanian Muslim populations (mainly secular and of the Sunni branch) are found throughout the country whereas Albanian Orthodox Christians as well as Bektashis are concentrated in the south and Roman Catholics are found in the north of the country.[129]

The first recorded Albanian Protestant was Said Toptani, who traveled around Europe, and in 1853 returned to Tirana and preached Protestantism. He was arrested and imprisoned by the Ottoman authorities in 1864. Mainline evangelical Protestants date back to the work of Congregational and later Methodist missionaries and the work of the British and Foreign Bible Society in the 19th century.

The Evangelical Alliance, which is known as VUSh, was founded in 1892. Today VUSh has about 160 member congregations from different Protestant denominations. VUSh organizes marches in Tirana including one against blood feuds in 2010. Bibles are provided by the Interconfessional Bible Society of Albania. The first full Albanian Bible to be printed was the Filipaj translation printed in 1990.

Seventh-day Adventist Church,[130][131] The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints,[132] and Jehovah's Witnesses[133] also have a number of adherents in Albania.

Albania was the only country in Europe where Jewish population experienced growth during the Holocaust.[134] After the mass emigration to Israel since the fall of Communist regime, only 200 Albanian Jews are left in the country today.[135][136]

According to 2008 statistics from the religious communities in Albania, there are 1119 churches and 638 mosques in the country. The Roman Catholic mission declared 694 Catholic churches. The Christian Orthodox community, 425 Orthodox churches. The Muslim community, 568 mosques and 70 Bektashi tekkes.[137][138]

Government and Politics

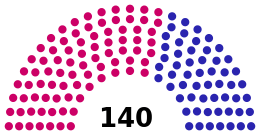

The Albanian republic is a parliamentary democracy established under a constitution renewed in 1998.[139] Elections are held every four years to the 140-seat unicameral Assembly of the Republic of Albania. In June 2002, a compromise candidate, Alfred Moisiu, former Army General, was elected to succeed President Rexhep Meidani. After parliamentary elections in July 2005, Sali Berisha, the leader of the Democratic Party, became prime minister, while on 20 July 2007 Bamir Topi became president. The current Albanian president Bujar Nishani was elected by Parliament in July 2012.

The Euro-Atlantic integration of Albania has been the ultimate goal of the post-communist governments. Albania's EU membership bid has been set as a priority by the European Commission.

Albania, along with Croatia, joined NATO on 1 April 2009, becoming the 27th and 28th members of the alliance.[140]

Executive branch

The head of state in Albania is the President of the Republic. The President is elected to a 5-year term by the Assembly by secret ballot, requiring a 50%+1 majority of the votes of all deputies. The current President of the Republic is Bujar Nishani elected in July 2012.

The President has the power to guarantee observation of the constitution and all laws, act as commander in chief of the armed forces, exercise the duties of the Assembly of the Republic of Albania when the Assembly is not in session, and appoint the Chairman of the Council of Ministers (prime minister).

Executive power rests with the Council of Ministers (cabinet). The Chairman of the Council (prime minister) is appointed by the president; ministers are nominated by the president on the basis of the prime minister's recommendation. The People's Assembly must give final approval of the composition of the Council. The Council is responsible for carrying out both foreign and domestic policies. It directs and controls the activities of the ministries and other state organs.

| President | Bujar Nishani | PD | 24 July 2012 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prime Minister | Edi Rama | PS | 15 September 2013 |

Legislative branch

The Assembly of the Republic of Albania (Kuvendi i Republikës së Shqipërisë) is the lawmaking body in Albania. There are 140 deputies in the Assembly, which are elected through a party-list proportional representation system. The President of the Assembly (or Speaker), who has two deputies, chairs the Assembly. There are 15 permanent commissions, or committees. Parliamentary elections are held at least every four years.

The Assembly has the power to decide the direction of domestic and foreign policy; approve or amend the constitution; declare war on another state; ratify or annul international treaties; elect the President of the Republic, the Supreme Court, and the Attorney General and his or her deputies; and control the activity of state radio and television, state news agency and other official information media.

Armed forces

Albanian Navy |

Albanian Army |

The Albanian Armed Forces (Forcat e Armatosura të Shqipërisë) were first formed after the country declared its independence in 1912. Albania reduced the number of active troops from 65,000 in 1988 to 14,500 in 2009.[141][142] The military now consists mainly of a small fleet of aircraft and sea vessels. In the 1990s, the country scrapped enormous amounts of obsolete hardware from China, such as tanks and SAM systems.

The armed forces currently include the General staff, the Albanian Land Force, the Albanian Air Force and the Albanian Naval Force. Increasing the military budget was one of the most important conditions for NATO integration. Military spending has generally been lower than 1.5% since 1996, only to peak in 2009 at 2% and fall again to 1.5%.[143] Since February 2008, Albania has participated officially in NATO's Operation Active Endeavor in the Mediterranean Sea.[144] It was invited to join NATO on 3 April 2008, and it became a full member on 2 April 2009.[145]

Administrative divisions

Albania is divided into 12 administrative counties (Albanian: qark or prefekturë). Since June 2015, these counties are divided into 61 municipalities (Albanian: bashki). These counties were further divided in 36 districts (Albanian: rreth) which became defunct in 2000.[146] The government introduced a new administrative division to be implemented in 2015 whereby municipalities are reduced to 61 in total, while rural ones called komuna are abolished. The defunct municipalities will be known as Neighborhoods or Villages (Albanian: Lagje / Fshat).[147][148] There are overall 2980 villages/communities (Albanian: fshat) in all Albania, formerly known as localities (Albanian: lokalitete). The municipalities are the first level of local governance, responsible for local needs and law enforcement.[149]

As part of the reform, major town centers in Albania are being physically redesigned and façades painted to reflect a more Mediterranean look.[150][151]

Crime and law enforcement

Law enforcement in Albania is primarily the responsibility of the Albanian Police. Albania also has a counter-terrorism unit called RENEA. Homicide is a problem in the country, especially blood feuds in rural areas of the north and domestic crime.[152] In 2014, about 3,000 Albanian families were estimated to be involved in blood feuds and this had since the fall of Communism led to the deaths of 10,000 people.[153]

Economy

Albania's transition from a socialist centrally planned economy to a capitalist mixed economy has been largely successful.[154] "Formal non-agricultural employment in the private sector more than doubled between 1999 and 2013," notes the World Bank, with much of this expansion powered by foreign investment.[155]

In 2012, Albania's GDP per capita (expressed in purchasing power parity) stood at 30% of the EU average, while AIC (Actual Individual Consumption) was 35%.[156] Albania, Cyprus, and Poland were the only countries in Europe to record economic growth in the first quarter of 2010.[157][158] The International Monetary Fund (IMF) predicted 2.6% growth for Albania in 2010 and 3.2% in 2011.[159] Unemployment has fluctuated around the 15% mark for the last decade.[160]

Agriculture remains the most significant sector of the economy. It employs 47.8% of the population, and about 24.31% of the land is used for agricultural purposes. Domestic farm products accounted for 63% of household expenditures and 25% of exports in 1990.

As part of the pre-accession process of Albania to the EU, farmers are being aided through IPA 2011 funds to improve Albanian agriculture standards.[161] Albania produces significant amounts of tobacco, olives, wheat, maize, potatoes, vegetables, fruits, sugar beets, grapes; meat, honey, dairy products, and traditional medicine and aromatic plants, figs (13th largest producer in the world)[162] and sour cherries.[163] Albania's proximity to the Ionian Sea and the Adriatic Sea give the underdeveloped fishing industry great potential. World Bank and European Community economists report that Albania's fishing industry has good potential to generate export earnings because prices in the nearby Greek and Italian markets are many times higher than those in the Albanian market. The fish available off the coasts of Albania are carp, trout, sea bream, mussels, and crustaceans.

Nearly all the country's electricity is generated by ageing hydroelectric power plants, which are becoming more ineffective due to increasing droughts.[164] There has been much private investment in a new generation of hydroelectric plants, such as Devoll Hydro Power Plant and the Ashta hydropower plant. Albania and Croatia have discussed the possibility of jointly building a nuclear power plant at Lake Shkoder, close to the border with Montenegro, a plan that has gathered criticism from Montenegro due to seismicity in the area.[165] In addition, there is some doubt whether Albania would be able to finance a project of such a scale with a total national budget of less than $5 billion.[7] However, in February 2009 Italian company Enel announced plans to build an 800 MW coal-fired power plant in Albania, to diversify electricity sources.[164]

.jpg)

The country has large deposits of petroleum and natural gas, and produced 26,000 barrels of oil per day in the first quarter of 2014 (BNK-TC).[166][167] Natural gas production, estimated at about 30 million m3, is sufficient to meet consumer demands.[7]

Other natural resources include coal, bauxite, copper and iron ore. Albania has the largest onshore oil reserves in Europe.

Tourism is gaining in its share of Albania's GDP, with visitors growing every year. Exports increased 300% during 2008–14, although their contribution to the GDP is still moderate (the value of exports per capita stands at $1,100). Albania's growth slowed in 2013, though tourism continued its dramatic expansion, and FDI maintained its upward trend as the government continued its modernization program.[154]

Science and technology

Internet in Albania is fast and inexpensive in comparison to the rest of Europe. For example, an ISP known as ABcom, offers a 30mbit download package for 306.999 lekë ($2.39579 USD) per month.[168] In the mobile network industry, providers such as Albanian Mobile Communications and Eagle Mobile provide both 3G and 4G data plans. From 1993 human resources in sciences and technology have drastically decreased. Various surveys show that during 1991–2005, approximately 50% of the professors and research scientists of the universities and science institutions in the country have emigrated.[169]

However, in 2009 the government approved the "National Strategy for Science, Technology and Innovation in Albania"[170] covering the period 2009–15. It aims to triple public spending on research and development (R&D) to 0.6% of GDP and augment the share of gross domestic expenditure on R&D from foreign sources, including via the European Union's Framework Programmes for Research, to the point where it covers 40% of research spending, among others.

Tourism

A significant part of Albania's national income derives from tourism. In 2014, it directly accounted for 6% of GDP, though including indirect contributions pushes the proportion to just over 20%.[171] Albania welcomed around 4.2 million visitors in 2012, mostly from neighbouring countries and the European Union. In 2011, Albania was recommended as a top travel destination, by Lonely Planet.[172] In 2014, Albania was nominated number 4 global touristic destination by the New York Times.[173] The number of tourists has increased by 20% for 2014 as well.

The bulk of the tourist industry is concentrated along the Adriatic and the Ionian Sea coast. The latter has the most beautiful and pristine beaches, and is often called the Albanian Riviera. The Albanian coastline has a considerable length of 360 kilometres (220 miles). The coast has a particular character because it is rich in varieties of sandy beaches, capes, coves, covered bays, lagoons, small gravel beaches, sea caves etc. Some parts of this seaside are very clean ecologically, which represent in this prospective unexplored areas, very rare in Mediterranean area.[174]

The increase in foreign visitors has been dramatic. Albania had only 500,000 visitors in 2005, while in 2012 had an estimated 4.2 million – an increase of 740% in only 7 years.

Seventy percent of Albania's terrain is mountainous and there are valleys that spread in a beautiful mosaic of forests, pastures, springs framed by high peaks capped by snow until late summer spreads across them.[175]

Albanian Alps, part of the Prokletije or Accursed Mountains range in Northern Albania bearing the highest mountain peak. The most beautiful mountainous regions that can be easily visited by tourists are Dajti Mountain, Thethi, Tropojë, Voskopoja, Valbona, Kelmend, Prespa, Lake Koman, Dukat and Shkrel.

National parks and World Heritage Sites

There are a number of associations of the tourism industry such as ATA, Unioni, etc.[176][177]

Albania is home to two World Heritage Sites (Berat and Gjirokastër are listed together)

- Butrint, an ancient Greek and Roman city

- Gjirokastër, a well-preserved Ottoman medieval town

- Berat, the 'town of a thousand and one windows'

The following is the UNESCO Tentative List of Albania:[178]

- Gashi River and Rrajca (latter part of Shebenik-Jabllanica National Park) under primeval beech forests of the Carpathians and the ancient beech forests of Germany

- Durrës Amphitheatre

- Ancient Tombs of Lower Selca

- Natural and Cultural Heritage of the Ohrid Region

- Ancient City of Apollonia

Most of the international tourists going to Albania are from Kosovo, Macedonia, Montenegro, Greece, and Italy.[179] Foreign tourists mostly come from Eastern Europe, particularly from Poland, and the Czech Republic, but also from Western European countries such as Germany, Belgium, Netherlands, France, Scandinavia, and others.

Transport

Highways

Currently, there are three main motorways in Albania: the dual carriageway connecting Durrës with Vlorë, the Albania–Kosovo Highway, and the Tirana–Elbasan Highway.

The A1 Albania–Kosovo Highway links Kosovo to Albania's Adriatic coast: the Albanian side was completed in June 2009,[181] and now it takes only two hours and a half to go from the Kosovo border to Durrës. Overall the highway will be around 250 km (155 mi) when it reaches Prishtina. The project was the biggest and most expensive infrastructure project ever undertaken in Albania. The cost of the highway appears to have breached €800 million, although the exact cost for the total highway has yet to be confirmed by the government.

Two additional highways will be built in Albania in the near future: Corridor VIII, which will link Albania with the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria, and the north-south highway, which corresponds to the Albanian side of the Adriatic–Ionian motorway, a larger regional highway connecting Croatia with Greece along the Adriatic and Ionian coasts. When all three corridors are completed Albania will have an estimated 759 kilometers of highway linking it with all its neighboring countries: Kosovo, the Republic of Macedonia, Montenegro, and Greece.

Aviation

Aviation in Albania marked its beginning in March 1926 when German airline Adria Aero Lloyd begin service between Tirana, Shkodër, Korçë and Vlorë. By 1924, the company had obtained a monopoly for all domestic routes. The project proved unprofitable, however, and Adria Aero Lloyd sold its concession to the Italian company Ala Littoria, which started air service in 1935 to several domestic and international destinations.[182]

The construction of a more modern airport in Laprakë started in 1934 and was completed by the end of 1935. This new airport, which was later officially named "Airport of Tirana", was constructed in conformity with optimal technological parameters of that time, with a reinforced concrete runway of 2,700 m (8,858 ft), and complemented with technical equipment and appropriate buildings. In 1938, Yugoslav carrier Aeroput introduced regular commercial flights linking Tirana with Belgrade with a landing in Dubrovnik.[183]

During 1955–57, the Rinasi Airport was constructed for military purposes. Later, its administration was shifted to the Ministry of Transport. On 25 January 1957 the State-owned Enterprise of International Air Transport (Albtransport) established its headquarters in Tirana. Aeroflot, Jat Airways, Malév, TAROM and Interflug were the air companies that started to have flights with Albania until 1960.[184]

During 1960–78, several airlines ceased to operate in Albania due to the self-imposed isolationism of the Communist government under Enver Hoxha, resulting in a decrease of influx of flights and passengers. In 1977 Albania's government signed an agreement with Greece to open the country's first air links with non-communist Europe. As a result, Olympic Airways was the first non-communist airline to commercially fly into Albania after World War II. By 1991 Albania had air links with many major European cities, including Paris, Rome, Zürich, Vienna and Budapest, but no regular domestic air service.[184]

A French–Albanian joint venture Ada Air, was launched in Albania as the first private airline, in 1991. The company offered flights in a thirty-six-passenger airplane four days a week between Tirana and Bari, Italy and a charter service for domestic and international destinations.[184]

From 1989 to 1991, because of political changes in the Eastern European countries, Albania adhered to the International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO), opened its air space to international flights, and had its duties of Air Traffic Control defined. As a result of these developments, conditions were created to separate the activities of air traffic control from Albtransport. Instead, the National Agency of Air Traffic (NATA) was established as an independent enterprise. In addition, during these years, governmental agreements of civil air transport were established with countries such as Bulgaria, Germany, Slovenia, Italy, Russia, Austria, the UK and Macedonia.

The Directory General of Civil Aviation (DGCA) was established on 3 February 1991, to cope with the development required by the time. Albania has one international airport, Tirana International Airport Nënë Tereza, which is linked to 29 destinations by 14 airlines. It has seen a dramatic rise in passenger numbers and aircraft movements since the early 1990s.

Railways

The railways in Albania are administered by the national railway company Hekurudha Shqiptare (HSH) (which means Albanian Railways). It operates a 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) gauge (standard gauge) rail system in Albania. All trains are hauled by Czech-built ČKD diesel-electric locomotives.

The railway system was extensively promoted by the totalitarian regime of Enver Hoxha, during which time the use of private transport was effectively prohibited. Since the collapse of the former regime, there has been a considerable increase in car ownership and bus usage. Whilst some of the country's roads are still in very poor condition, there have been other developments (such as the construction of a motorway between Tirana and Durrës) which have taken much traffic away from the railways.

Education

Before the establishment of the People's Republic, Albania's illiteracy rate was as high as 85%. Schools were scarce between World War I and World War II. When the People's Republic was established in 1945, the Party gave high priority to wiping out illiteracy. As part of a vast social campaign, anyone between the ages of 12 and 40 who could not read or write was mandated to attend classes to learn. By 1955, illiteracy was virtually eliminated among Albania's adult population.[35]

Today the overall literacy rate in Albania is 98.7%; the male literacy rate is 99.2% and female literacy rate is 98.3%.[7] With large population movements in the 1990s to urban areas, the provision of education has undergone transformation as well. The University of Tirana is the oldest university in Albania, having been founded in October 1957.

-

360° panoramic view of Mother Teresa Square by night with University of Tirana campus at the center

Culture

Art

Albanian art has a long and eventful history. Albania, a country of southeastern Europe, has a unique culture from that of other European countries. The Ottoman Empire ruled over Albania for nearly five centuries, which greatly affected the country's artwork and artistic forms. After Albania's joining with the Ottoman Empire in 1478, Ottoman influenced art forms such as mosaics and muralpaintings became prevalent, and no real artistic change occurred until Albanian Liberation in 1912.

Following mosaics and murals of antiquity and the Middle Ages, the first paintings were icons Byzantine Orthodox tradition. Albanian earliest icons date from the late thirteenth century and generally estimated that their artistic peak reached in the eighteenth century. Among the most prominent representatives of the Albanian iconographic art were Onufri and David Selenica. The museums of Berat, Korca and Tirana good collections remaining icons. By the end of the Ottoman period, the painting was limited mostly to folk art and ornate mosques.[185]

Paintings and sculpture arose in the first half of the twentieth century and reached a modest peak in the 1930s and 1940s, when the first organized art exhibitions at national level.[185] Contemporary Albanian artwork captures the struggle of everyday Albanians, however new artists are utilizing different artistic styles to convey this message. Albanian artists continue to move art forward, while their art still remains distinctively Albanian in content. Though among Albanian artist post-modernism was fairly recently introduced, there is a number of artists and works known internationally. Among most famous Albanian post-modernist are considered Anri Sala, Sislej Xhafa, and Helidon Gjergji.

Music and folklore

Albanian folk music falls into three stylistic groups, with other important music areas around Shkodër and Tirana; the major groupings are the Ghegs of the north and southern Labs and Tosks. The northern and southern traditions are contrasted by the "rugged and heroic" tone of the north and the "relaxed" form of the south. Southern instrumental music includes the sedate kaba, an ensemble-driven by a clarinet or violin alongside accordions and llautës. The kaba is an improvised and melancholic style with melodies that Kim Burton describes as "both fresh and ancient", "ornamented with swoops, glides and growls of an almost vocal quality", exemplifying the "combination of passion with restraint that is the hallmark of Albanian culture."

These disparate styles are unified by "the intensity that both performers and listeners give to their music as a medium for patriotic expression and as a vehicle carrying the narrative of oral history", as well as certain characteristics like the use of rhythms such as 3/8, 5/8 and 10/8.[186] The first compilation of Albanian folk music was made by two Himariots song artists Neço Muka and Koço Çakali in 1929 and 1931 in Paris during their interpretations with the Albanian song diva Tefta Tashko Koço. Several gramophone compilations were recorded in those years by this genial trio of Albanian artists which eventually led to the recognition of the Himariot Isopolyphonic Music as an UNESCO World Heritage.[187]

Albanian folk songs can be divided into major groups, the heroic epics of the north, and the sweetly melodic lullabies, love songs, wedding music, work songs and other kinds of song. The music of various festivals and holidays is also an important part of Albanian folk song, especially those that celebrate St. Lazarus Day, which inaugurates the springtime. Lullabies and vajtims are very important kinds of Albanian folk song, and are generally performed by solo women.[188]

Albanian language and literature

.jpg)

Albanian was proved to be an Indo-European language in 1854 by the German philologist Franz Bopp. The Albanian language comprises its own branch of the Indo-European language family.

Most scholars argue that Albanian derives from Illyrian[189] while some others[190] claim that it derives from Daco-Thracian. (Illyrian and Daco-Thracian, however, might have been closely related languages; see Thraco-Illyrian.)

Establishing longer relations, Albanian is often compared to Balto-Slavic on the one hand and Germanic on the other, both of which share a number of isoglosses with Albanian. Moreover, Albanian has undergone a vowel shift in which stressed, long o has fallen to a, much like in the former and opposite the latter. Likewise, Albanian has taken the old relative jos and innovatively used it exclusively to qualify adjectives, much in the way Balto-Slavic has used this word to provide the definite ending of adjectives.

The cultural renaissance was first of all expressed through the development of the Albanian language in the area of church texts and publications, mainly of the Catholic region in the North, but also of the Orthodox in the South. The Protestant reforms invigorated hopes for the development of the local language and literary tradition when cleric Gjon Buzuku brought into the Albanian language the Catholic liturgy, trying to do for the Albanian language what Luther did for German.

Meshari (The Missal) by Gjon Buzuku, published in 1555, is considered the first literary work of written Albanian. The refined level of the language and the stabilised orthography must be the result of an earlier tradition of written Albanian, a tradition that is not well understood. However, there is some fragmented evidence, pre-dating Buzuku, which indicates that Albanian was written from at least the 14th century.

The earliest evidence dates from 1332 AD with a Latin report from the French Dominican Guillelmus Adae, Archbishop of Antivari, who wrote that Albanians used Latin letters in their books although their language was quite different from Latin. Other significant examples include: a baptism formula (Unte paghesont premenit Atit et Birit et spertit senit) from 1462, written in Albanian within a Latin text by the Bishop of Durrës, Pal Engjëlli; a glossary of Albanian words of 1497 by Arnold von Harff, a German who had travelled through Albania, and a 15th-century fragment of the Bible from the Gospel of Matthew, also in Albanian, but written in Greek letters.

Albanian writings from these centuries must not have been religious texts only, but historical chronicles too. They are mentioned by the humanist Marin Barleti, who, in his book Rrethimi i Shkodrës (The Siege of Shkodër) (1504), confirms that he leafed through such chronicles written in the language of the people (in vernacula lingua) as well as his famous biography of Skanderbeg Historia de vita et gestis Scanderbegi Epirotarum principis (History of Skanderbeg) (1508). The History of Skanderbeg is still the foundation of Scanderbeg studies and is considered an Albanian cultural treasure, vital to the formation of Albanian national self-consciousness.

During the 16th to 17th centuries, the catechism E mbësuame krishterë (Christian Teachings) (1592) by Lekë Matrënga, Doktrina e krishterë (The Christian Doctrine) (1618) and Rituale romanum (1621) by Pjetër Budi, the first writer of original Albanian prose and poetry, an apology for George Castriot (1636) by Frang Bardhi, who also published a dictionary and folklore creations, the theological-philosophical treaty Cuneus Prophetarum (The Band of Prophets) (1685) by Pjetër Bogdani, the most universal personality of Albanian Middle Ages, were published in Albanian. The most famous Albanian writer is probably Ismail Kadare.

Sports

Popular sports in Albania include Football, weightlifting, basketball, volleyball, tennis, swimming, rugby union, and gymnastics. Football is the most popular sport in Albania. It is governed by the Football Association of Albania (Albanian: Federata Shqiptare e Futbollit, F.SH.F.), which was created in 1930 and has membership in FIFA and UEFA.

Football arrived in Albania early in the 20th century when the inhabitants of the northern city of Shkodër were surprised to see a strange game being played by students at a Christian mission. The sport swiftly grew in popularity in a country then under Ottoman Empire rule. Albania was the winner of the 1946 Balkan Cup and the Malta Rothmans International Tournament 2000, but had never participated in any major UEFA or FIFA tournament, until UEFA Euro 2016, Albania's first ever appearance at the continental tournament and at a major men's football tournament. Albania scored their first ever goal in a major tournament and secured their first ever win in European Championship when they beat Romania by 1–0 in a UEFA Euro 2016 match on 19 June 2016.[191][192]

Media

Radio Televizioni Shqiptar (RTSH) is the public radio and TV broadcaster of Albania, founded by King Zog in 1938. RTSH runs three analogue television stations as TVSH Televizioni Shqiptar, four digital thematic stations as RTSH, and three radio stations using the name Radio Tirana. In addition, 4 regional radio stations serve in the four extremities of Albania.The international service broadcasts radio programmes in Albanian and seven other languages via medium wave (AM) and short wave (SW).[193] The international service has used the theme from the song "Keputa një gjethe dafine" as its signature tune. The international television service via satellite was launched since 1993 and aims at Albanian communities in Kosovo, Serbia, Macedonia, Montenegro and northern Greece, plus the Albanian diaspora in the rest of Europe. RTSH has a past of being heavily influenced by the ruling party in its reporting, whether that party be left or right wing.

According to the Albanian Media Authority, AMA, Albania has an estimated 257 media outlets, including 66 radio stations and 67 television stations, with three national, 62 local and more than 50 cable TV stations. Last years Albania has organized several shows as a part of worldwide series like Dancing with the Stars, Big Brother Albania, Albanians Got Talent, The Voice of Albania, and X Factor Albania.

Cuisine

The cuisine of Albania – as with most Mediterranean and Balkan nations – is strongly influenced by its long history. At different times, the territory which is now Albania has been claimed or occupied by Greece, Serbia, Italy and the Ottoman Turks and each group has left its mark on Albanian cuisine. The main meal of Albanians is the midday meal, which is usually accompanied by a salad of fresh vegetables such as tomatoes, cucumbers, green peppers and olives with olive oil, vinegar and salt. It also includes a main dish of vegetables and meat. Though it is used in several dishes, pumpkins are more commonly displayed and traditionally given as gifts throughout Albania, especially in the region of Berat. Seafood specialties are also common in the coastal cities of Durrës, Sarandë and Vlorë. In high elevation localities, smoked meat and pickled preserves are common.

-

Cannoli very popular in Arbëreshë Regions

-

Tarator is a chilled yogurt and cucumber drink

-

Byrek

-

Albanian Baklava

-

Stuffed Paprika with rice,tomato sauce and mince meat

-

Traditional dish from Hasi Region

-

Albanian Japrak

-