Anabolic-androgenic steroids abuse

Research data indicates that steroids affect the serotonin and dopamine neurotransmitter systems of the brain.[2] In an animal study, male rats developed a conditioned place preference to testosterone injections into the nucleus accumbens, an effect blocked by dopamine antagonists, which suggests that androgen reinforcement is mediated by the brain. Moreover, testosterone appears to act through the mesolimbic dopamine system, a common substrate for drugs of abuse. Nonetheless, androgen reinforcement is not comparable to that of cocaine, nicotine, or heroin. Instead, testosterone resembles other mild reinforcers, such as caffeine, or benzodiazepines. The potential for androgen addiction remains to be determined.[3]

Anabolic steroids are not psychoactive and cannot be detected by stimuli devices like a pupilometer which makes them hard to spot as a source of neuropsychological imbalaces in some AAS users.

Abuse potential

The Diagnostic Statistical Manual IV (DSM IV) and the International Classification of Diseases, Volume 10 (ICD 10) differ in the way they regard Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids' (AAS) potential for producing dependence.

DSM IV regards AAS as potentially dependence producing. ICD 10 however regards them as non-dependence producing.[4] Anabolic steroids are not physically addictive but users can develop a psychological dependence on the physical result.[5]

Diagnostic Statistical Manual

For DSM-IV, anabolic-androgenic steroid dependency is found in the “other substance-related disorder” (include inhalants, anabolic steroids, medications) section and can be coded, depending on which diagnostic criteria are met.[6]

International Classification of Diseases

ICD–10 criteria for dependence include experience of at least three of the following during the past year:[7]

- a strong desire to take steroids

- difficulty in controlling use

- withdrawal syndrome when use is reduced

- evidence of tolerance

- neglect of other interests and persistent use despite harmful consequences

However, the following ICD-10-CM Index entries contain back-references to ICD-10-CM F55.3:[8]

- Abuse

- hormones F55.5

- steroids F55.5

- drug NEC (non-dependent) F19.10

- hormones F55.5

- steroids F55.5

- non-psychoactive substance NEC F55.8

- hormones F55.5

- steroids F55.5

ICD-10 goes on to state that “although it is usually clear that the patient has a strong motivation to take the substance, there is no development of dependence or withdrawal symptoms as in the case of the psychoactive substances.”[6]

ICD-9-CM will be replaced by ICD-10-CM beginning October 1, 2014, therefore, F55.3 and all other ICD-10-CM diagnosis codes should only be used for training or planning purposes until then.

National Institute on Drug Abuse

The National Institute on Drug Abuse (NIDA) says that "even though anabolic steroids do not cause the same high as other drugs, steroids are reinforcing and can lead to addiction. Studies have shown that animals will self-administer steroids when given the opportunity, just as they do with other addictive drugs. People may persist in abusing steroids despite physical problems and negative effects on social relationships, reflecting these drugs’ addictive potential. Also, steroid abusers typically spend large amounts of time and money obtaining the drug; another indication of addiction. Individuals who abuse steroids can experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking them, including mood swings, fatigue, restlessness, loss of appetite, insomnia, reduced sex drive, and steroid cravings, all of which may contribute to continued abuse. One of the most dangerous withdrawal symptoms is depression. When depression is persistent, it can sometimes lead to suicidal thoughts. Research has found that some steroid abusers turn to other drugs such as opioid to counteract the negative effects of steroids."[9]

Causes and treatment

Male anabolic-androgenic steroid abusers often have a troubled social background.[10]

Childhood trauma

25% of male weightlifters reported memories of childhood physical or sexual abuse in an interview. Anabolic steroids are sometimes used by people with muscle dysmorphia (a very specific type of body dysmorphic disorder (BDD)) as a defense mechanism.[11] Interestingly, yohimbine, while it was originally considered a flop of a supplement, because it did not increase testosterone levels as first suspected, have at higher doses been discovered to be useful to facilitate recall of traumatic memories in the treatment of post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).[12]

Illicit use by groups

Criminals

Anabolic steroid use has been associated with an antisocial lifestyle involving various types of criminality.[13]

Governments

Law enforcement

Steroid abuse among law enforcement is considered a problem by some. "It's a big problem, and from the number of cases, it's something we shouldn't ignore. It's not that we set out to target cops, but when we're in the middle of an active investigation into steroids, there have been quite a few cases that have led back to police officers," says Lawrence Payne, a spokesman for the United States Drug Enforcement Administration.[14] The FBI Law Enforcement Bulletin stated that “Anabolic steroid abuse by police officers is a serious problem that merits greater awareness by departments across the country".[15] It is also believed that police officers across the United Kingdom "are using criminals to buy steroids and abuse their power for sexual gratification" which he claims to be a top risk factor for police corruption.[16]

Sports

Professional wrestling

Following the murder-suicide of Chris Benoit in 2007, the Oversight and Government Reform Committee investigated steroid usage in the wrestling industry.[17] The Committee investigated WWE and Total Nonstop Action Wrestling (TNA), asking for documentation of their companies' drug policies. WWE CEO and Chairman, Linda and Vince McMahon respectively, both testified. The documents stated that 75 wrestlers—roughly 40 percent—had tested positive for drug use since 2006, most commonly for steroids.[18][19]

References

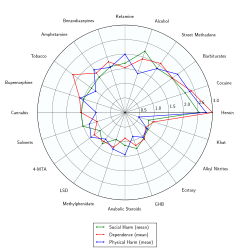

- ↑ Nutt, D; King, LA; Saulsbury, W; Blakemore, C (24 March 2007). "Development of a rational scale to assess the harm of drugs of potential misuse.". Lancet (London, England). 369 (9566): 1047–53. PMID 17382831.

- ↑ Dopinglinkki > Anabolic steroids induce long-term changes in the brain

- ↑ Wood RI (November 2004). "Reinforcing aspects of androgens". Physiol. Behav. 83 (2): 279–89. doi:10.1016/j.physbeh.2004.08.012. PMID 15488545.

- ↑ Midgley SJ, Heather N, Davies JB (1999). "Dependence-Producing Potential of Anabolic-Androgenic Steroids". Addiction Research & Theory. 7 (6): 539–550. doi:10.3109/16066359909004404.

- ↑ "The price of steroids | Men's Fitness UK". Mensfitness.co.uk. 2008-09-03. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- 1 2 Scally MC, Tan RS (October 2009). "Complexities in clarifying the diagnostic criteria for anabolic-androgenic steroid dependence". Am J Psychiatry. 166 (10): 1187; author reply 1188. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.2009.09060846. PMID 19797448.

- ↑ Rashid H, Ormerod S, Day E (2007). "Anabolic androgenic steroids: What the psychiatrist needs to know". Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 13 (3): 203–211. doi:10.1192/apt.bp.105.000935.

- ↑ "2014 ICD-10-CM Diagnosis Code F55.3 : Abuse of steroids or hormones". Icd10data.com. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ↑ "DrugFacts: Anabolic Steroids | National Institute on Drug Abuse". Drugabuse.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ↑ Skarberg K, Engstrom I (2007). "Troubled social background of male anabolic-androgenic steroid abusers in treatment". Subst Abuse Treat Prev Policy. 2: 20. doi:10.1186/1747-597X-2-20. PMC 1995193

. PMID 17615062.

. PMID 17615062. - ↑ "Why do people abuse anabolic steroids? | National Institute on Drug Abuse". Drugabuse.gov. Retrieved 2013-12-01.

- ↑ van der Kolk, Bessel A. (1995). "The Treatment of Post Traumatic Stress Disorder". In Hobfoll, Stevan E.; De Vries, Marten W. Extreme stress and communities: impact and intervention. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers. pp. 421–44. ISBN 978-0-7923-3468-2.

- ↑ Klötz F, Garle M, Granath F, Thiblin I (November 2006). "Criminality among individuals testing positive for the presence of anabolic androgenic steroids". Arch. Gen. Psychiatry. 63 (11): 1274–9. doi:10.1001/archpsyc.63.11.1274. PMID 17088508.

- ↑ Keeping, Juliana (27 December 2010). "Steroid abuse among law enforcement a problem nationwide". The Ann Arbor News. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ "Anabolic Steroid Use and Abuse by Police Officers: Policy & Prevention". The Police Chief. June 2008. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ "Chief constable admits police officers across UK 'are using criminals to buy steroids and abuse their power for sexual gratification'". Daily Mail. 22 January 2013. Retrieved 1 December 2013.

- ↑ Brian Lockhart (2010-03-01). "WWE steroid investigation: A controversy McMahon 'doesn't need'". Greenwich Time. Retrieved 2010-03-01.

- ↑ documents Archived December 24, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Deposition details McMahon steroid testimony | News from southeastern Connecticut". The Day. 2007-12-13. Retrieved 2010-08-14.