Soleus muscle

| Soleus muscle | |

|---|---|

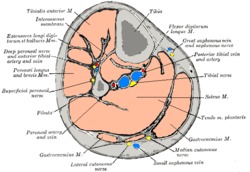

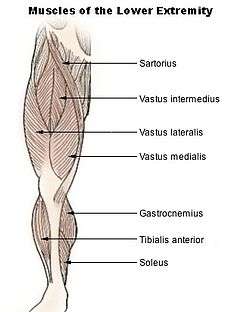

Muscles of lower extremity | |

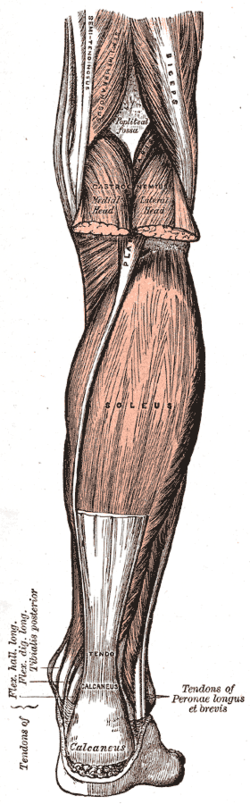

The soleus muscle and surrounding structures, from Gray's Anatomy. This is a view of the back of the right leg; most of the gastrocnemius muscle has been removed. | |

| Details | |

| Origin | fibula, medial border of tibia (soleal line) |

| Insertion | tendo calcaneus |

| Artery | popliteal artery, posterior tibial artery, peroneal artery |

| Nerve | tibial nerve, specifically, nerve roots L5–S2 |

| Actions | plantarflexion |

| Antagonist | tibialis anterior |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Musculus soleus |

| TA | A04.7.02.047 |

| FMA | 22542 |

In humans and some other mammals, the soleus is a powerful muscle in the back part of the lower leg (the calf). It runs from just below the knee to the heel, and is involved in standing and walking. It is closely connected to the gastrocnemius muscle and some anatomists consider them to be a single muscle, the triceps surae. Its name is derived from the Latin word "solea", meaning "sandal".

Structure

The soleus is located in the superficial posterior compartment of the leg. Not all mammals have a soleus muscle; one familiar species that lacks the soleus is the dog. Soleus is vestigial in the horse.[1]

The soleus exhibits significant morphological differences across species. It is unipennate in many species. In some animals, such as the rabbit, it is fused for much of its length with the gastrocnemius muscle. In the human, soleus is a complex multi-pennate muscle, usually having a separate (posterior) aponeurosis from the gastrocnemius muscle. A majority of soleus muscle fibers originate from each side of the anterior aponeurosis, attached to the tibia and fibula.[2][3] Other fibers originate from the posterior (back) surfaces of the head of the fibula and its upper quarter, as well as the middle third of the medial border of the tibia.

The fibers originating from the anterior surface of the anterior aponeurosis insert onto the median septum and the fibers originating from the posterior surface of the anterior aponeurosis insert onto the posterior aponeurosis.[2][3] The posterior aponeurosis and median septum join in the lower quarter of the muscle and then join with the anterior aponeuroses of the gastrocnemius muscles to form the calcaneal tendon or Achilles tendon and inserts onto the posterior surface of the calcaneus, or heel bone.

In contrast to some animals, the human soleus and gastrocnemius muscles are relatively separate, such that shear can be detected between the soleus and gastrocnemius aponeuroses.[4]

Relations

The gastrocnemius muscle is superficial to (closer to the skin than) the soleus, which lies below the gastrocnemius.

The plantaris muscle and a portion of its tendon run between the two muscles. Deep to it (farther from the skin) is the transverse intermuscular septum, which separates the superficial posterior compartment of the leg from the deep posterior compartment.

On the other side of the fascia are the tibialis posterior muscle, the flexor digitorum longus muscle, and the flexor hallucis longus muscle, along with the posterior tibial artery and posterior tibial vein and the tibial nerve.

Since the anterior compartment of the leg is lateral to the tibia, the bulge of muscle medial to the tibia on the anterior side is actually the posterior compartment. The soleus is superficial middle of the tibia.

Function

The action of the calf muscles, including the soleus, is plantarflexion of the foot (that is, they increase the angle between the foot and the leg). They are powerful muscles and are vital in walking, running, and dancing. The soleus specifically plays an important role in maintaining standing posture; if not for its constant pull, the body would fall forward.

Also, in upright posture, the soleus is responsible for pumping venous blood back into the heart from the periphery, and is often called the skeletal-muscle pump, peripheral heart or the sural (tricipital) pump.[5]

Soleus muscles have a higher proportion of slow muscle fibers than many other muscles. In some animals, such as the guinea pig and cat, soleus consists of 100% slow muscle fibers.[6][7] Human soleus fiber composition is quite variable, containing between 60 and 100% slow fibers.[8]

The soleus is the most effective muscle for plantarflexion in a bent knee position. This is because the gastrocnemius originates on the femur, so bending the leg limits its effective tension. During regular movement (i.e. walking) the soleus is the primary muscle utilized for plantarflexion due to the slowtwitch fibers resisting fatigue.[9]

Clinical significance

Disease

Due to the thick fascia covering the muscles of the leg, they are prone to compartment syndrome. This pathology relates to the inflammation of tissue affecting blood flow and compressing nerves. If left untreated compartment syndrome can lead to atrophy of muscles, blood clots, and neuropathy.[10]

Additional images

|

References

- ↑ Meyers, Ron A.; Hermanson, John W. (2006). "Horse Soleus Muscle: Postural Sensor or Vestigial Structure?" (PDF). The Anatomical Record Part A: Discoveries in Molecular, Cellular, and Evolutionary Biology. 288 (10): 1068–1076. doi:10.1002/ar.a.20377. PMID 16952170.

- 1 2 Agur, Anne M.; Ng-Thow-Hing, Victor; Ball, Kevin A.; Fiume, Eugene; McKee, Nanacy Hunt (2003). "Documentation and Three-Dimensional Modelling of Human Soleus Muscle Architecture". Clinical Anatomy. 16 (4): 285–293. doi:10.1002/ca.10112. PMID 12794910.

- 1 2 Hodgson, JA; Finni, T; Lai, AM; Edgerton, VR; Sinha, S (May 2006). "Influence of structure on the tissue dynamics of the human soleus muscle observed in MRI studies during isometric contractions". J Morphol. 5 (267): 584–601. doi:10.1002/jmor.10421. PMID 16453292.

- ↑ Bojsen-Møller, Jens; Hansen, Philip; Aagaard, Per; Svantesson, Ulla; Kjaer, Michael; Magnusson, S. Peter (2004). "Differential displacement of the human soleus and medial gastrocnemius aponeuroses during isometric plantar flexor contractions in vivo". J Appl Physiol. 97 (5): 1908–1914. doi:10.1152/japplphysiol.00084.2004. PMID 15220297.

- ↑ Botta G, Piccinetti A, Giontella M, Mancini S (2001). "Il potenziamento dell'attività di pompa venosa del tricipite surale in ortopedia e traumatologia mediante l'utilizzo di una nuova apparecchiatura di ginnastica vascolare" [Strengthening of venous pump activity of the sural tricipital in orthopaedics and traumatology by means of a new equipment for vascular exercise] (PDF). Giornale Italiano di Ortopedia e Traumatologia (in Italian). 27: 84–8.

- ↑ Ariano MA, Armstrong RB, Edgerton VR (January 1973). "Hindlimb muscle fiber populations of five mammals". The Journal of Histochemistry and Cytochemistry. 21 (1): 51–5. doi:10.1177/21.1.51. PMID 4348494.

- ↑ Burke RE, Levine DN, Salcman M, Tsairis P (May 1974). "Motor units in cat soleus muscle: physiological, histochemical and morphological characteristics". The Journal of Physiology. 238 (3): 503–14. doi:10.1113/jphysiol.1974.sp010540. PMC 1330899

. PMID 4277582.

. PMID 4277582. - ↑ Gollnick PD, Sjödin B, Karlsson J, Jansson E, Saltin B (April 1974). "Human soleus muscle: a comparison of fiber composition and enzyme activities with other leg muscles". Pflügers Archiv. 348 (3): 247–55. doi:10.1007/BF00587415. PMID 4275915.

- ↑ Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2007. Print.

- ↑ MedlinePlus Encyclopedia Compartment syndrome

- Gray, Henry. Pick, T. Pickering, & Howden, Robert (Eds.) (1995). Gray's Anatomy (15th ed.). New York: Barnes & Noble Books.

- Saladin, Kenneth S. Anatomy & Physiology: The Unity of Form and Function. 6th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, 2007. Print.

External links

- Anatomy photo:15:st-0414 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- A. Agur. Architecture of the human soleus muscle, three-dimensional computer modelling of cadaveric muscle and ultrasonographic documentation in vivo. University of Toronto (PhD Thesis). ((https://tspace.library.utoronto.ca/bitstream/1807/16553/1/NQ59030.pdf))