Population history of indigenous peoples of the Americas

The population figure for indigenous peoples in the Americas before the 1492 voyage of Christopher Columbus has proven difficult to establish. Scholars rely on archaeological data and written records from settlers from the Old World. Most scholars writing at the end of the 19th century estimated that the pre-Columbian population was as low as 10 million; by the end of the 20th century most scholars gravitated to a middle estimate of around 50 million, with some historians arguing for an estimate of 100 million or more.[1] Contact with the New World led to the European colonization of the Americas, in which millions of immigrants from the Old World eventually settled in the New World.

The population of African and Eurasian peoples in the Americas grew steadily, while the indigenous population plummeted. Eurasian diseases such as influenza, bubonic plague and pneumonic plagues devastated the Native Americans who did not have immunity to them. Conflict and outright warfare with Western European newcomers and other American tribes further reduced populations and disrupted traditional societies. The extent and causes of the decline have long been a subject of academic debate, along with its characterization as a genocide.[2]

Population overview

Given the fragmentary nature of the evidence, even semi-accurate pre-Columbian population figures are impossible to obtain. Scholars have varied widely on the estimated size of the indigenous populations prior to colonization and on the effects of European contact.[3] Estimates are made by extrapolations from small bits of data. In 1976, geographer William Denevan used the existing estimates to derive a "consensus count" of about 54 million people. Nonetheless, more recent estimates still range widely.[4]

Using an estimate of approximately 37 million people in Mexico, Central and South America in 1492 (including 6 million in the Aztec Empire, 5-10 million in the Mayan States, 11 million in what is now Brazil, and 12 million in the Inca Empire), the lowest estimates give a death toll due from disease of 90% by the end of the 17th century (nine million people in 1650).[5] Latin America would match its 15th-century population early in the 19th century; it numbered 17 million in 1800, 30 million in 1850, 61 million in 1900, 105 million in 1930, 218 million in 1960, 361 million in 1980, and 563 million in 2005.[5] In the last three decades of the 16th century, the population of present-day Mexico dropped to about one million people.[5] The Maya population is today estimated at six million, which is about the same as at the end of the 15th century, according to some estimates.[5] In what is now Brazil, the indigenous population declined from a pre-Columbian high of an estimated four million to some 300,000.

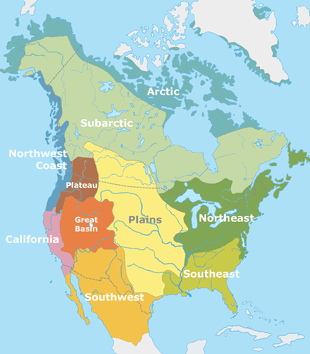

While it is difficult to determine exactly how many Natives lived in North America before Columbus,[6] estimates range from a low of 2.1 million[7] to 7 million[8] people to a high of 18 million[9]

The Aboriginal population of Canada during the late 15th century is estimated to have been between 200,000[10] and two million,[11] with a figure of 500,000 currently accepted by Canada's Royal Commission on Aboriginal Health.[12] Repeated outbreaks of Old World infectious diseases such as influenza, measles and smallpox (to which they had no natural immunity), were the main cause of depopulation. This combined with other factors such as dispossession from European/Canadian settlements and numerous violent conflicts resulted in a forty- to eighty-percent aboriginal population decrease after contact.[10] For example, during the late 1630s, smallpox killed over half of the Wyandot (Huron), who controlled most of the early North American fur trade in what became Canada. They were reduced to fewer than 10,000 people.[13]

Historian David Henige has argued that many population figures are the result of arbitrary formulas selectively applied to numbers from unreliable historical sources. He believes this is a weakness unrecognized by several contributors to the field, and insists there is not sufficient evidence to produce population numbers that have any real meaning. He characterizes the modern trend of high estimates as "pseudo-scientific number-crunching." Henige does not advocate a low population estimate, but argues that the scanty and unreliable nature of the evidence renders broad estimates inevitably suspect, saying "high counters" (as he calls them) have been particularly flagrant in their misuse of sources.[14] Many population studies acknowledge the inherent difficulties in producing reliable statistics, given the scarcity of hard data.

The population debate has often had ideological underpinnings.[15] Low estimates were sometimes reflective of European notions of cultural and racial superiority. Historian Francis Jennings argued, "Scholarly wisdom long held that Indians were so inferior in mind and works that they could not possibly have created or sustained large populations."[16]

The indigenous population of the Americas in 1492 was not necessarily at a high point and may actually have been in decline in some areas. Indigenous populations in most areas of the Americas reached a low point by the early 20th century. In most cases, populations have since begun to climb.[17]

Pre-Columbian Americas

Genetic diversity and population structure in the American land mass using DNA micro-satellite markers (genotype) sampled from North, Central, and South America have been analyzed against similar data available from other indigenous populations worldwide.[18][19] The Amerindian populations show a lower genetic diversity than populations from other continental regions.[19] Observed is both a decreasing genetic diversity as geographic distance from the Bering Strait occurs and a decreasing genetic similarity to Siberian populations from Alaska (genetic entry point).[18][19] Also observed is evidence of a higher level of diversity and lower level of population structure in western South America compared to eastern South America.[18][19] A relative lack of differentiation between Mesoamerican and Andean populations is a scenario that implies coastal routes were easier than inland routes for migrating peoples (Paleo-Indians) to traverse.[18] The overall pattern that is emerging suggests that the Americas were recently colonized by a small number of individuals (effective size of about 70), and then they grew by a factor of 10 over 800 – 1000 years.[20][21] The data also show that there have been genetic exchanges between Asia, the Arctic and Greenland since the initial peopling of the Americas.[21][22]

Depopulation from disease

According to Noble David Cook, a community of scholars have recently, albeit slowly, "been quietly accumulating piece by piece data on early epidemics in the Americas and their relation to subjugation of native peoples." They now believe that widespread epidemic disease, to which the natives had no prior exposure or resistance, was the primary cause of the massive population decline of the Native Americans.[23] Earlier explanations for the population decline of the American natives include the European immigrants' accounts of the brutal practices of the Spanish conquistadores, as recorded by the Spanish themselves. This was applied through the encomienda which was a system ostensibly set up to protect people from warring tribes as well as to teach them the Spanish language and the Catholic religion, but in practice was tantamount to serfdom and slavery.[24] The most notable account was that of the Dominican friar Bartolomé de las Casas, whose writings vividly depict Spanish atrocities committed in particular against the Taínos. It took five years for the Taíno rebellion to be quelled by both the Real Audiencia—through diplomatic sabotage, and through the Indian auxiliaries fighting with the Spanish.[25] After Emperor Charles V personally eradicated the notion of the encomienda system as a use for slave labour, there were not enough Spanish to have caused such a large population decline.[26][27] The second European explanation was a perceived divine approval, in which God removed the natives as part of His "divine plan" to make way for a new Christian civilization. Many Native Americans viewed their troubles in terms of religious or supernatural causes within their own belief systems.

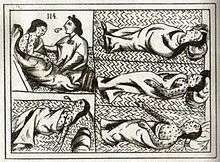

Soon after Europeans and Africans arrived in the New World, bringing with them the infectious diseases of Europe and Africa, observers noted immense numbers of indigenous Americans began to die from these diseases. One reason this death toll was overlooked is that once introduced, the diseases raced ahead of European immigration in many areas. Disease killed a sizable portion of the populations before European written records were made. After the epidemics had already killed massive numbers of natives, many newer European immigrants assumed that there had always been relatively few indigenous peoples. The scope of the epidemics over the years was tremendous, killing millions of people—possibly in excess of 90% of the population in the hardest hit areas—and creating one of "the greatest human catastrophe in history, far exceeding even the disaster of the Black Death of medieval Europe",[23] which had killed up to one-third of the people in Europe and Asia between 1347 and 1351.

One of the most devastating diseases was smallpox, but other deadly diseases included typhus, measles, influenza, bubonic plague, cholera, malaria, tuberculosis, mumps, yellow fever and pertussis, which were chronic in Eurasia.[28]

This transfer of disease between the Old and New Worlds was later studied as part of what has been labeled the "Columbian Exchange".

The epidemics had very different effects in different regions of the Americas. The most vulnerable groups were those with a relatively small population and few built-up immunities. Many island-based groups were annihilated. The Caribs and Arawaks of the Caribbean nearly ceased to exist, as did the Beothuks of Newfoundland. While disease raged swiftly through the densely populated empires of Mesoamerica, the more scattered populations of North America saw a slower spread.

Virulence and mortality

Viral and bacterial diseases that kill victims before the illnesses spread to others tend to flare up and then die out. A more resilient disease would establish an equilibrium; if its victims lived beyond infection, the disease would spread further. The evolutionary process selects against quick lethality, with the most immediately fatal diseases being the most short-lived. A similar evolutionary pressure acts upon victim populations, as those lacking genetic resistance to common diseases die and do not leave descendants, whereas those who are resistant procreate and pass resistant genes to their offspring. For example, in the first fifty years of the sixteenth century, an unusually strong strain of syphilis killed a high proportion of infected Europeans within a few months; over time, however, the disease has become much less virulent.

Thus both infectious diseases and populations tend to evolve towards an equilibrium in which the common diseases are non-symptomatic, mild or manageably chronic. When a population that has been relatively isolated is exposed to new diseases, it has no resistance to the new diseases (the population is "biologically naive"). These people die at a much higher rate, resulting in what is known as a "virgin soil" epidemic. Before the European arrival, the Americas had been isolated from the Eurasian-African landmass. The peoples of the Old World had had thousands of years for their populations to accommodate to their common diseases.

The fact that all members of an immunologically naive population are exposed to a new disease simultaneously increases the fatalities. In populations where the disease is endemic, generations of individuals acquired immunity; most adults had exposure to the disease at a young age. Because they were resistant to reinfection, they are able to care for individuals who caught the disease for the first time, including the next generation of children. With proper care, many of these "childhood diseases" are often survivable. In a naive population, all age groups are affected at once, leaving few or no healthy caregivers to nurse the sick. With no resistant individuals healthy enough to tend to the ill, a disease may have higher fatalities.

The natives of the Americas were faced with several new diseases at once creating a situation where some who successfully resisted one disease might die from another. Multiple simultaneous infections (e.g., smallpox and typhus at the same time) or in close succession (e.g., smallpox in an individual who was still weak from a recent bout of typhus) are more deadly than just the sum of the individual diseases. In this scenario, death rates can also be elevated by combinations of new and familiar diseases: smallpox in combination with American strains of yaws, for example.

Other contributing factors:

- Native American medical treatments such as sweat baths and cold water immersion (practiced in some areas) weakened some patients and probably increased mortality rates.[29]

- Europeans brought many diseases with them because they had many more domesticated animals than the Native Americans. Domestication usually means close and frequent contact between animals and people, which is an opportunity for diseases of domestic animals to mutate and migrate into the human population.[30]

- The Eurasian landmass extends many thousands of miles along an east–west axis. Climate zones also extend for thousands of miles, which facilitated the spread of agriculture, domestication of animals, and the diseases associated with domestication. The Americas extend mainly north and south, which, according to the environmental determinist theory popularized by Jared Diamond in Guns, Germs, and Steel, meant that it was much harder for cultivated plant species, domesticated animals, and diseases to migrate.

Biological warfare

When Old World diseases were first carried to the Americas at the end of the fifteenth century, they spread throughout the southern and northern hemispheres, leaving the indigenous populations in near ruins.[28][31] No evidence has been discovered that the earliest Spanish colonists and missionaries deliberately attempted to infect the American natives, and some effort was actually made to limit the devastating effects of disease before it killed off what remained of their forced slave labor under their encomienda system.[28][31] The cattle introduced by the Spanish polluted the water reserves which Native Americans dug in the fields to accumulate rain water. In response, the Franciscans and Dominicans created public fountains and aqueducts to guarantee access to drinking water.[5] But when the Franciscans lost their privileges in 1572, many of these fountains were not guarded any more and deliberate well poisoning may have happened.[5] Although no proof of such poisoning has been found, some historians believe the decrease of the population correlates with the end of religious orders' control of the water.[5]

In the centuries that followed, accusations and discussions of biological warfare were common. Documented accounts of incidents involving both threats and acts of deliberate infection are numerous, and may have occurred more frequently than scholars have previously acknowledged.[32][33] Many of the instances likely went unreported, and it is possible that documents relating to such acts were deliberately destroyed,[33] or sanitized.[34][35] By the middle of the 18th century, colonists had the knowledge and technology to attempt biological warfare with the smallpox virus. They well understood the concept of quarantine, and that contact with the sick could infect the healthy with smallpox, and those who survived the illness would not be infected again. Whether the threats were carried out, or how effective individual attempts were, is uncertain.[28][33][34]

One such threat was delivered by fur trader James McDougall, who is quoted as saying to a gathering of local chiefs, "You know the smallpox. Listen: I am the smallpox chief. In this bottle I have it confined. All I have to do is to pull the cork, send it forth among you, and you are dead men. But this is for my enemies and not my friends."[36] Likewise, another fur trader threatened Pawnee Indians that if they didn't agree to certain conditions, "he would let the smallpox out of a bottle and destroy them." The Reverend Isaac McCoy was quoted in his History of Baptist Indian Missions as saying that the white men had deliberately spread smallpox among the Indians of the southwest, including the Pawnee tribe, and the havoc it made was reported to General Clark and the Secretary of War.[36][37] Artist and writer George Catlin observed that Native Americans were also suspicious of vaccination, "They see white men urging the operation so earnestly they decide that it must be some new mode or trick of the pale face by which they hope to gain some new advantage over them."[38] So great was the distrust of the settlers that the Mandan chief Four Bears denounced the white man, whom he had previously treated as brothers, for deliberately bringing the disease to his people.[39][40][41]

During the Seven Years' War, British militia took blankets from their smallpox hospital and gave them as gifts to two neutral Lenape Indian dignitaries during a peace settlement negotiation, according to the entry in the Captain's ledger, "To convey the Smallpox to the Indians".[34][42][43] In the following weeks, the high commander of the British forces in North America conspired with his Colonel to "Extirpate this Execreble Race" of Native Americans, writing, ""Could it not be contrived to send the small pox among the disaffected tribes of Indians? We must on this occasion use every stratagem in our power to reduce them." His Colonel agreed to try.[33][42] On the deliberate communication of smallpox to Native Americans during the 1836-40 epidemic, historian Ann F. Ramenofsky in 1987 wrote, "Variola Major can be transmitted through contaminated articles such as clothing or blankets. In the nineteenth century, the U. S. Army sent contaminated blankets to Native Americans, especially Plains groups, to control the Indian problem."[44] While specific responsibility for the 1836-40 smallpox epidemic remains in question, scholars have asserted that the Great Plains epidemic was "started among the tribes of the upper Missouri River by failure to quarantine steam boats on the river",[36] and Captain Pratt of the St. Peter "was guilty of contributing to the deaths of thousands of innocent people. The law calls his offense criminal negligence. Yet in light of all the deaths, the almost complete annihilation of the Mandans, and the terrible suffering the region endured, the label criminal negligence is benign, hardly befitting an action that had such horrendous consequences."[40] Well into the 20th century, deliberate infection attacks continued as Brazilian settlers and miners transported infections intentionally to the native groups whose lands they coveted."[31]

Vaccination

After Edward Jenner's 1796 demonstration that the smallpox vaccination worked, the technique became better known and smallpox became less deadly in the United States and elsewhere. Many colonists and natives were vaccinated, although, in some cases, officials tried to vaccinate natives only to discover that the disease was too widespread to stop. At other times, trade demands led to broken quarantines. In other cases, natives refused vaccination because of suspicion of whites. In 1831, government officials vaccinated the Yankton Sioux at Sioux Agency. The Santee Sioux refused vaccination and many died.[15]

Other causes of depopulation

War and violence

While epidemic disease was a leading factor of the population decline of the American indigenous peoples after 1492, there were other contributing factors, all of them related to European contact and colonization. One of these factors was warfare. According to demographer Russell Thornton, although many lives were lost in wars over the centuries, and war sometimes contributed to the near extinction of certain tribes, warfare and death by other violent means was a comparatively minor cause of overall native population decline.[45]

From the U.S. Bureau of the Census in 1894: "The Indian wars under the government of the United States have been more than 40 in number. They have cost the lives of about 19,000 white men, women and children, including those killed in individual combats, and the lives of about 30,000 Indians. The actual number of killed and wounded Indians must be very much higher than the given... Fifty percent additional would be a safe estimate..."[46]

There is some disagreement among scholars about how widespread warfare was in pre-Columbian America,[47] but there is general agreement that war became deadlier after the arrival of the Europeans and their firearms. Europeans had gunpowder and swords, which made killing easier and war more deadly. Europeans proved consistently successful in achieving domination in warfare with Native Americans for a variety of reasons. One reason was the staying power of the Europeans, who could call on a far ranging supply network, and could sustain a conflict over several years including the winters if necessary. Almost no Indian tribe had the stored resources to conduct a war for more than a few months. European colonization also contributed to a number of wars between Native Americans, who fought over which of them should have first access to the new weapon.[48]

Empires such as the Incas depended on a highly centralized administration for the distribution of resources. Disruption caused by the war and the colonization hampered the traditional economy, and possibly led to shortages of food and materials.

Exploitation

Some Spaniards objected to the encomienda system, notably Bartolomé de las Casas, who insisted that the Indians were humans with souls and rights. Due to many revolts and military encounters, Emperor Charles V helped relieve the strain on both the Indian laborers and the Spanish vanguards probing the Caribana for military and diplomatic purposes.[49] Later on New Laws were promulgated in Spain in 1542 to protect isolated natives, but the abuses in the Americas were never entirely or permanently abolished. The Spanish also employed the pre-Columbian draft system called the mita,[50] and treated their subjects as something between slaves and serfs. Serfs stayed to work the land; slaves were exported to the mines, where large numbers of them died. In other areas the Spaniards replaced the ruling Aztecs and Incas and divided the conquered lands among themselves ruling as the new feudal lords with often, but unsuccessful lobbying to the viceroys of the Spanish crown to pay Tlaxcalan war demnities. The infamous Bandeirantes from São Paulo, adventurers mostly of mixed Portuguese and native ancestry, penetrated steadily westward in their search for Indian slaves. Serfdom existed as such in parts of Latin America well into the 19th century, past independence.

Massacres

Friar Bartolomé de las Casas and Antonius Flávio Chesta (Tony Chesta) and other dissenting Spaniards from the colonial period described the manner in which the natives were treated by colonials. This has helped to create an image of the Spanish conquistadores as cruel in the extreme.

Great revenues were drawn from Hispaniola so the advent of losing manpower didn't benefit the Spanish crown. At best, the reinforcement of vanguards sent by the Council of the Indies to explore the Caribana country and gather information on alliances or hostilities was the main goal of the local viceroys and their adelantados.[51] Although mass killings and atrocities were not a significant factor in native depopulation, no mainstream scholar dismisses the sometimes humiliating circumstances now believed to be precipitated by civil disorder as well as Spanish cruelty.[52][53]

- The Taínos in the Antilles (Some believe 80% of the population disappeared in thirty years).[5] In 1518–1519 a devastating smallpox epidemic killed most of the region's indigenous population.[54]

- The Pequot War in early New England.

- In mid-19th century Argentina, post-independence leaders Juan Manuel de Rosas and Julio Argentino Roca engaged in what they presented as a "Conquest of the Desert" against the natives of the Argentinian interior, leaving over 1,300 indigenous dead.[55][56]

- While some California tribes were settled on reservations, others were hunted down and massacred by 19th century American settlers. It is estimated that some 4,500 people of the Population of Native California suffered violent deaths between 1849 and 1870.[57][58]

Displacement and disruption

Even more consequential than warfare or mistreatment on indigenous populations was the geographic displacement of Native American tribes. The increased European population due to immigration and high birth rates of Native European settlers put pressure on native tribes to relocate and alter their traditional ways of life. Displacement of native peoples living traditionally often resulted in increased infant mortality and often higher death rates which steadily lowered their populations for some time. In the United States, for example, the relocations of Native Americans resulting from the policies of Indian removal and the reservation system created a disruption which resulted in fewer live births and a short term population decline.

The populations of many Native American peoples were reduced by the common practice of intermarrying with Europeans.[59] Although many Indian cultures that once thrived are extinct today, their descendants exist today in some of the bloodlines of the current inhabitants of the Americas.

Formal apology - United States

On 8 September 2000, the head of the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs (BIA) formally apologized for the agency's participation in the "ethnic cleansing" of Western tribes.[60][61][62]

See also

- Amazonas before the Inca Empire

- First Nations

- Genocides in the Americas

- List of Indian reserves in Canada by population

- Native American massacres

- Population of Canada

- Population of Native California

- Smallpox epidemics in the New World

- Trail of Tears

- Uncontacted peoples

- Guatemalan genocide

- Selknam genocide

References

Notes

- ↑ Taylor, Alan (2002). American colonies; Volume 1 of The Penguin history of the United States, History of the United States Series. Penguin. p. 40. ISBN 9780142002100. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

- ↑ David E. Stannard (1993-11-18). American Holocaust: The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- ↑ Michael R. Haines; Richard H. Steckel (2000). A Population History of North America. Cambridge University Press. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-521-49666-7.

- ↑ 20th century estimates in Thornton, p. 22; Denevan's consensus count; recent lower estimates. Archived 28 October 2004 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "La catastrophe démographique" (The Demographical Catastrophe"), L'Histoire n°322, July–August 2007, p. 17.

- ↑ "Microchronology and Demographic Evidence Relating to the Size of Pre-Columbian North American Indian Populations". Science 16 June 1995: Vol. 268. no. 5217, pp. 1601–1604 doi:10.1126/science.268.5217.1601.

- ↑ Ubelaker, Douglas H. (1976-11-01). "Prehistoric New World population size: Historical review and current appraisal of North American estimates". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 45 (3): 661–665. doi:10.1002/ajpa.1330450332. ISSN 1096-8644.

- ↑ Thornton, Russell (1990). American Indian holocaust and survival: a population history since 1492. University of Oklahoma Press. pp. 26–32. ISBN 0-8061-2220-X.

- ↑ Dobyns, Henry (1983). Their Number Become Thinned: Native American Dynamics in Eastern North America. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press.

- 1 2 Northcott, Herbert C; Wilson, Donna M (2008). Dying and Death in Canada. Toronto: University of Toronto Press. pp. 25–27. ISBN 978-1-55111-873-4. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ Thornton, Russell (2000). "Population history of Native North Americans". In Michael R. Haines, Richard Hall Steckel. A population history of North America. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 13. ISBN 0-521-49666-7. Retrieved 20 June 2010.

- ↑ Bailey, Garrick Alan (2008). Handbook of North American Indians: Indians in contemporary society. Government Printing Office. p. 285. ISBN 0-16-080388-8. Retrieved 14 January 2011.

- ↑ Robertson, Ronald G (2001). Rotting face : smallpox and the American Indian. Caldwell, Idaho: Caxton Press. pp. 107–108. ISBN 0-87004-419-2.

- ↑ Henige, p. 182.

- 1 2 Krech III, Shepard (1999). The ecological Indian: myth and history (1 ed.). New York: W. W. Norton & Company, Inc. pp. 81–84. ISBN 0-393-04755-5.

- ↑ Jennings 1993, p. 83

- ↑ Thornton, pp. xvii, 36.

- 1 2 3 4 Wang S; Lewis CM; Jakobsson M; Ramachandran S; Ray N; Bedoya G; Rojas W; Parra MV; Molina JA; Gallo C; Mazzotti G; Poletti G; Hill K; Hurtado AM; Labuda D; Klitz W; Barrantes R; Bortolini MC; Salzano FM; Petzl-Erler ML; Tsuneto LT; Llop E; Rothhammer F; Excoffier L; Feldman MW; Rosenberg NA; Ruiz-Linares A. (2007). "Genetic Variation and Population Structure in Native Americans". PLoS Genet. 3 (11): e185. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.0030185. PMC 2082466

. PMID 18039031.

. PMID 18039031. - 1 2 3 4 "Joint match probabilities for Y chromosomal and autosomal markers" (PDF). Forensic Science International. 2008. pp. 174, 234–238. Retrieved 3 February 2010.

- ↑ Wells, Spencer; Read, Mark (2002). The Journey of Man - A Genetic Odyssey (Digitised online by Google books). Random House. pp. 138–140. ISBN 0-8129-7146-9. Retrieved 21 November 2009.

- 1 2 Hey J (2005). "On the number of New World founders: a population genetic portrait of the peopling of the Americas". PLoS Biol. 3 (6): e193. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0030193. PMC 1131883

. PMID 15898833. Retrieved 7 October 2013.

. PMID 15898833. Retrieved 7 October 2013. - ↑ Wade, Nicholas (2010). "Ancient Man In Greenland Has Genome Decoded". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- 1 2 Cook, Noble David. Born To Die; Cambridge University Press ;1998; pp. 1-14.

- ↑ Junius P. Rodriguez (2007). Encyclopedia of slave resistance and rebellion. 1. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 184. ISBN 978-0-313-33272-2. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ↑ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioLife. p. 199. ISBN 978-1-113-14760-8. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ↑ David M. Traboulay (1994). Columbus and Las Casas: the conquest and Christianization of America, 1492–1566. University Press of America. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8191-9642-2. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ↑ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioLife. p. 192. ISBN 978-1-113-14760-8. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 The First Horseman: Disease in Human History; John Aberth; Pearson-Prentice Hall (2007); Pgs. 47-75(51)

- ↑ Cook, p. 208; Thornton, p. 47.

- ↑ Jared Diamond (1997). Guns, germs, and steel: the fates of human societies. W. W. Norton & Company. p. 357. ISBN 978-0-393-03891-0.

- 1 2 3 Cook; Pgs. 205-216

- ↑ Empire of Fortune; Francis Jennings; W. W. Norton & Company; 1988; Pgs. 200, 447-8

- 1 2 3 4 Fenn, Elizabeth A. Biological Warfare in Eighteenth-Century North America: Beyond Jeffery Amherst; The Journal of American History, Vol. 86, No. 4, March, 2000

- 1 2 3 The Tainted Gift; Barbara Alice Mann; ABC-CLIO; 2009; Pgs. 1-18

- ↑ Cherokee Medicine, Colonial Germs: An Indigenous Nation's Fight Against Smallpox, 1518–1824; Paul Kelton; University of Oklahoma Press; 2015; Pgs. 102-105

- 1 2 3 The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian; Esther Wagner Stearn, Allen Edwin Stearn; University of Minnesota; 1945; Pgs. 13-20, 73-94, 97

- ↑ Chardon's Journal at Fort Clark, 1834-1839; Annie Heloise Abel; Books for Libraries Press; 1932; Pgs. 319, 394

- ↑ Princes and Peasants: Smallpox in History; Donald R. Hopkins; University of Chicago Press; 1983; Pgs.270-271

- ↑ Robert Blaisdell ed., Great Speeches by Native Americans, p. 116.

- 1 2 Rotting Face: Smallpox and the American Indian; R. G. Robertson; Caxton Press; 2001 Pgs. 80-83; 298-312

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Plague and Pestilence: From Ancient Times to the Present; George C. Kohn; Pgs. 252-253

- 1 2 Pontiac and the Indian Uprising; Peckham, Howard H.; University of Chicago Press; 1947; Pgs. 170, 226-7

- ↑ Crucible of War: The Seven Years' War and the Fate of Empire in British North America, 1754-1766; Anderson, Fred; New York: Knopf; 2000; Pgs. 541-2, 809n11; ISBN 0-375-40642-5

- ↑ Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact; University of New Mexico Press; 1987; p. 147-148

- ↑ War not a major cause : Thornton, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Report on Indians taxed and Indians not taxed in the United States (except Alaska). U.S. Government Printing Office. 1994 [1894]. p. 637.

- ↑ W. D. Rubinstein (2004). Genocide: A History. Pearson Education. p. 12. ISBN 978-0-582-50601-5.

- ↑ Increased deadliness of warfare, see for example Hanson, ch. 6. See also flower war.

- ↑ David M. Traboulay (1994). Columbus and Las Casas: the conquest and Christianization of America, 1492–1566. University Press of America. p. 44. ISBN 978-0-8191-9642-2. Retrieved 11 July 2010.

- ↑ Bolivia - Ethnic Groups.

- ↑ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioLife. p. 395. ISBN 978-1-113-14760-8. Retrieved 14 July 2010.

- ↑ Anghiera Pietro Martire D' (July 2009). De Orbe Novo, the Eight Decades of Peter Martyr D'Anghera. BiblioLife. p. 198. ISBN 978-1-113-14760-8. Retrieved 10 July 2010.

- ↑ Jay O. Sanders. "The Great Inca Rebellion". Retrieved 30 June 2010.

- ↑ Kohn, George C. (2008). Encyclopedia of plague and pestilence: from ancient times to the present. Infobase Publishing. p. 160. ISBN 0-8160-6935-2.

- ↑ Cook, p. 212.

- ↑ Carlos A. Floria and César A. García Belsunce, 1971. Historia de los Argentinos I and II; ISBN 84-599-5081-6.

- ↑ Minorities During the Gold Rush. Archived 4 August 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ For example, The Oxford Companion to American Military History (Oxford University Press, 1999) states that "if Euro-Americans committed genocide anywhere on the continent against Native Americans, it was in California."

- ↑ Indian Mixed-Blood.

- ↑ "An apology from the BIA". tahtonka (Global Culture, Exploring the Humanities of Humans). 2000. Retrieved 21 February 2010.

- ↑ Kevin Gover (2006) [Sep 8, 2000]. Video of Kevin Gover’s speech, "Never Again" (Sept. 8, 2000), a formal apology to Native Americans, on behalf of the U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs (video). U.S. Bureau of Indian Affairs, analog to digital conversion by Harkirat Chawia, Michigan State University, presented by Christopher Buck, Michigan State University.

- ↑ Buck, Christopher (2006). ""Never Again"; Kevin Gover's Apology for the Bureau of Indian Affairs" (PDF). Wicazo SA Review. 21 (1 (Spring)): 97–126. JSTOR 4140301. Retrieved Oct 12, 2015.

Bibliography

- Books

- Cappel, Constance (2007). The smallpox genocide of the Odawa tribe at L'Arbre Croche, 1763: the history of a Native American people. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-5220-6.

- Noble David Cook (1998). Born to Die: Disease and New World Conquest, 1492-1650. ISBN 978-0-521-62208-0.

- Victor Davis Hanson (2002-08-27). Carnage and culture: landmark battles in the rise of Western power. Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-50052-1.

- David P. Henige (1998). Numbers from Nowhere: The American Indian Contact Population Debate. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-3044-6.

- Jennings, Francis (1993). The Founders of America: How Indians discovered the land, pioneered in it, and created great classical civilizations, how they were plunged into a Dark Age by invasion and conquest, and how they are reviving. New York: Norton. ISBN 0-393-03373-2.

- Charles C. Mann (2005-08-09). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf. ISBN 9781400040063.

- Ramenofsky, Ann (1988). Vectors of Death: The Archaeology of European Contact. Albuquerque, New Mexico: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-0997-6.

- Royal, Robert. 1492 and All That: Political Manipulations of History. Washington, D.C.: Ethics and Public Policy Center, 1992.

- Shoemaker, Nancy (1999). American Indian population recovery in the twentieth century. University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1919-X.

- David E. Stannard (1993-11-18). American Holocaust:The Conquest of the New World. Oxford University Press, USA. ISBN 978-0-19-508557-0.

- Stearn, E. Wagner and Allen E. Stearn. The Effect of Smallpox on the Destiny of the Amerindian. Boston: Humphries, 1945.

- Thornton, Russel (1987). American Indian Holocaust and Survival: ˜a Œpopulation History Since 1492. Norman : University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 978-0-8061-2074-4.

- Online sources

- Lewy, Guenter. "Were American Indians the Victims of Genocide?", History News Network, originally published in Commentary.

- Lord, Lewis. How many people were here before Columbus? at the Wayback Machine (archived 22 September 2006), 10 August 1997.

- Rummel, R.J. Death by Government, Chapter 3: Pre-Twentieth Century Democide

- Stutz, Bruce. Megadeath in Mexico Discover, 21 February 2006.

- White, Matthew. "The Annihilation of the Native Americans". Amateur website, but reports data from scholarly sources.

- Jeffrey Amherst and Smallpox Blankets "Lord Jeffrey Amherst's letters discussing germ warfare against American Indians" Retrieved February 2007

Further reading

- Brian M. Fagan (2005-05-20). Ancient North America: The Archaeology of a Continent. ISBN 978-0-500-28532-9.

- Charles C. Mann (2005-08-09). 1491: New Revelations of the Americas Before Columbus. Knopf. ISBN 9781400040063.

- William Hardy McNeill (1998). Plagues and peoples. Anchor. ISBN 978-0-385-12122-4.

- Michael Sletcher, 'North American Indians', in Will Kaufman and Heidi Macpherson, eds., Britain and the Americas: Culture, Politics, and History, (2 vols., Oxford, 2005).

- Cappel, Constance (2007). The smallpox genocide of the Odawa tribe at L'Arbre Croche, 1763: the history of a Native American people. Edwin Mellen Press. ISBN 0-7734-5220-6.

External links

- Aboriginal peoples populations - Statistics Canada

- Article by Russell Thornton on American Indian population history in North America

- Article by Alan Rinding on Brazil's Indians

- Colonial Brazil: Portuguese, Tupi, etc

- Indigenous Genocide in the Brazilian Amazon

- The theft of Native Americans' land, in one animated map

- Indian land cession by years

- Pope Francis apologises for Catholic crimes against indigenous peoples during the colonisation of the Americas (2015)

.svg.png)