Hotel Theresa

|

Hotel Theresa | |

|

from the north (2006) | |

| |

| Location |

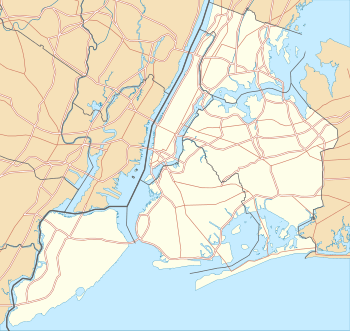

2082-2096 Adam Clayton Powell, Jr. Blvd. Manhattan, New York City |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 40°48′31″N 73°56′58″W / 40.80861°N 73.94944°WCoordinates: 40°48′31″N 73°56′58″W / 40.80861°N 73.94944°W |

| Built | 1912-13[1] |

| Architect | George & Edward Blum |

| NRHP Reference # | 05000618[2] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | June 16, 2005 |

| Designated NYCL | July 13, 1993 |

The Hotel Theresa, located at 2082-96 Adam Clayton Powell Jr. Boulevard between West 124th and 125th Streets in the Harlem neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City, was, in the mid-20th century, a vibrant center of African American life in the area and the city.

The 13-story hotel was built in 1912-13 by German-born stockbroker Gustavus Sidenberg (1843–1915), whose wife the hotel is named after,[3] and was designed by the firm of George & Edward Blum, who specialized in designing apartment buildings. The hotel, which was known in its heyday as "the Waldorf of Harlem", exemplifies the Blums' inventive use of terra-cotta for ornamentation, and has been called "one of the most visually striking structures in northern Manhattan."[1]

The building, now an office building known as Theresa Towers, was designated a New York City landmark in 1993[1] and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2005.[2]

History

The 13-story[4] hotel – with its striking white terra cotta facade with ornamentation made specifically for the project and not pre-fabricated stock items, as was standard practice[1] – opened in 1913 and was, until the construction of the Adam Clayton Powell Jr. State Office Building across the street in 1973, the tallest building in Harlem. It was primarily an apartment hotel, but also accepted temporary guest as well.[1] In its early years the hotel accepted only white guests, but it was bought in 1937 by Love B. Woods, an African American businessman, who in 1940 ended its racial segregation policy.[3][4]

The hotel had a two-story penthouse dining room which features views of Long Island Sound to the east and the Palisades to the west,[4] as well as a bar and grill. In the 1940s and 1950s, the Theresa became a center of the social life of the black community of Harlem; it was then that it was known as "the Waldorf of Harlem." The hotel profited from the refusal of prestigious hotels elsewhere in the city to accept black guests. As a result, black businessmen, performers, and athletes were thrown under the same roof. The building was also the location of such institutions as A. Philip Randolph's March on Washington Movement, the March Community Bookstore, and the Organization of Afro-American Unity created by Malcolm X[1] after he left the Nation of Islam.

In 1960 Fidel Castro came to New York for the opening session of the United Nations, and, after storming out of the Hotel Shelburne in Midtown Manhattan because of the manager's demand for payment in cash, he and his entourage stayed at the Theresa,[5] where they rented 80 rooms for $800 per day.[6] According to the New York Times, Castro felt that "Negroes would be more sympathetic" to his cause, and indeed he drew enthusiastic crowds of supporters, along with some protesters.[1] While Castro was there, he was visited by Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev, as well as by such luminaries as Malcolm X, poets Langston Hughes and Allen Ginsberg, Gamal Abdel Nasser, the president of Egypt, and Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru of India.[1] Subsequent to Castro's visit, other Third World leaders, such as Patrice Lumumba of the Belgian Congo, chose to stay at the Theresa.[1]

In October 1960, John F. Kennedy campaigned for the presidency at the hotel, along with Eleanor Roosevelt and other leading figures in the Democratic Party.

Ron Brown, who was the United States Secretary of Commerce in the Clinton administration grew up in the hotel, where his father worked as manager, and U.S. Congressman Charles Rangel (D-Harlem) once worked there as a desk clerk.

The hotel suffered from the continued deterioration of Harlem through the 1950s and 1960s, and, ironically, from the end of segregation elsewhere in the city. As African Americans of means now had alternatives, they stopped coming to Harlem. The owners had not upgraded or modernized the hotel in decades, and it was said to be "dowdy" at best.[1]

New owners began converting the building to office space beginning in 1966,[1] and the hotel closed in 1967. The building was renovated and restored, with the exterior largely kept as it had originally been, instead of being replaced with an aluminum and glass facade, an alternative which had been considered.[1] The building reopened in 1970[1] as Theresa Towers, though a sign with the old name is still painted on the side of the building, and the old name is still commonly used. As well as housing commercial and professional tenants, it serves as an auxiliary campus for Columbia University's Teachers College and the Touro College of Pharmacy.

Notable guests, tenants and employees

|

|

In popular culture

- Some scenes of Alfred Hitchcock's movie Topaz, the plot of which revolves around the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis, are set in and in front of the Hotel Theresa.

- The Hotel Theresa is one of the settings in the novel Push and the film Precious (2009). Precious' Each One Teach One alternative school is on the "nineteenth floor".

- WLIB-1190 AM (known as Harlem Radio Center) maintained studios here from 1952-1962.

See also

- List of New York City Landmarks

- List of former hotels in Manhattan

- National Register of Historic Places listings in New York County, New York

References

Notes

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 Dolkart, Andrew S. "Hotel Theresa Designation Report" New York Landmarks Preservation Commission (July 13, 1993)

- 1 2 National Park Service (2010-07-09). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 Aberjhani. "Hotel Theresa" in Aberjhani and West, Sandra L. (eds.) Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance, Facts On File, 2003. p.158

- 1 2 3 Aaron, Amanda. "Hotel Theresa" in Jackson, Kenneth T., ed. (2010), The Encyclopedia of New York City (2nd ed.), New Haven: Yale University Press, ISBN 978-0-300-11465-2, pp.618-19

- 1 2 Fernandez, Manny (September 24, 2007). "New York Grudgingly Opens Door to Ahmadinejad". The New York Times. Retrieved 2011-11-03.

- ↑ Wilson, Sondra Kathryn. Meet Me at the Theresa : The Story of Harlem's Most Famous Hotel, 2004. p.205

Sources

- Popkik, Barry. "Waldorf of Harlem" (June 4, 2005)

External links

![]() Media related to Hotel Theresa at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Hotel Theresa at Wikimedia Commons