History of Tampa, Florida

Tampa /ˈtæmpə/, a United States city in Hillsborough County on the west coast of the state of Florida.

Human habitation in the Tampa Bay area can be traced back thousands of years. The Manasota culture is the earliest documented group, spanning from about 500 BCE until about 700 CE, by which time it had evolved into the Safety Harbor culture. The Tocobaga and the Pohoy were of this culture, and these were the dominant tribes living along the northern shore of Tampa Bay when Spanish explorers arrived in the early 1500s. Though Spain claimed all of Florida as its possession, it could not successfully establish a settlement on the west coast and did not attempt to do so after the mid-1500s. However, European contact with native peoples spread diseases which devastated local populations. By the mid-1600s, indigenous social structures had collapsed, and the Tampa Bay area was left largely uninhabited.

Tampa's modern history can be traced to the founding of Fort Brooke at the mouth of the Hillsborough River in today's downtown in 1824, soon after the United States had taken possession of Florida from Spain. The outpost brought a small population of civilians to the area, and the town of Tampa was first incorporated in 1855.

Growth came slowly and sporadically for the village of Tampa during its first half-century, as poor transportation links, conflicts with the Seminole tribe, and repeated outbreaks of yellow fever made development difficult. The United States Civil War and Reconstruction were especially tough times, so much so that the city government disincorporated for over a decade.

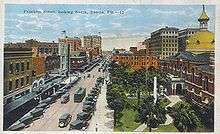

Tampa's fortunes shifted dramatically beginning in the 1880s with the construction of the first railroad links to the town and the development of thriving cigar and phosphate industries. Of particular importance was the founding of the cigar-centered neighborhood of Ybor City in 1885, which brought a huge influx of Cubans, Spaniards, Italians, and a handful of other immigrants to what had previously been a typical small southern town. These changes combined to bring sudden prosperity and explosive growth - Tampa's population jumped from less than 800 residents in 1880 to over 15,000 in 1900, making it one of the largest cities in Florida.

Growth continued through the 20th century as Tampa emerged as a modern financial, trade, and commercial hub. The number of residents exceeded 100,000 during the 1930s, 250,000 during the 1950s, and 300,000 during the 1990s. The land area of Tampa also grew by many times during the 20th century, most notably when the city annexed the neighboring communities of West Tampa in 1925, Sulphur Springs and Palma Ceia in 1953, Port Tampa in 1961, and New Tampa in 1988.

This rapid growth did not come without problems. In the first half of the 20th century, Tampa became nationally notorious for its rampant organized crime activity and an atmosphere of general lawlessness, including open electoral fraud and repeated instances of unpunished vigilantism against African-Americans and the city's large immigrant population. Later, the city suffered through a period of racial unrest in the wake of desegregation.

By the turn of the 21st century, ethics reforms and a diversifying economy brought the city a period of more stable growth. Civic emphasis has been on redeveloping run-down areas of the urban core, particularly portions of Ybor City and the downtown waterfront.

Etymology

There is some dispute as to the origin and meaning of the name "Tampa". It is believed to mean "sticks of fire" in the language of the Calusa, a Native American tribe that once lived south of the area. This may relate to the high concentration of lightning strikes that west central Florida receives every year during the summer months. Other historians claim the name refers to "the place to gather sticks". Toponymist George R. Stewart writes that the name was the result of a miscommunication between the Spanish and the Indians, the Indian word being "itimpi", meaning simply "near it".[1]

The name first appears in the memoir of Hernando de Escalante Fontaneda from 1575, who had spent 17 years as a Calusa captive. He calls it "Tanpa" and describes it as an important Calusa town. While "Tanpa" may be the basis for the modern name "Tampa", archaeologist Jerald Milanich places the Calusa village of Tanpa at the mouth of Charlotte Harbor near current day Pineland. Map maker Bernard Romans found certain difficulties in translating earlier Spanish-era maps of Florida for English use and may have accidentally transferred the name north to Tampa Bay, the next large inlet up the west coast of Florida.[2]

European exploration and early history

Indigenous population

Archeological evidence indicates that the shores of Tampa Bay have been inhabited for thousands of years. Artifacts suggest that early inhabitants of the region relied on the sea for most of their resources, and a vast majority of inhabited sites have been found on or near the shoreline.

At the time of European contact in the 16th century, the Safety Harbor culture dominated the area, with indigenous peoples loosely organized into three or four chiefdoms on the shores of the bay. The Tocobaga's principal town was located at the northern end of Old Tampa Bay near today's Safety Harbor in Pinellas County. Uzita controlled the south shore of Tampa Bay, from the Little Manatee River to Sarasota Bay. Mocoso was on the east side of Tampa Bay, on the Alafia River and, possibly, the Hillsborough River. There may have been a fourth independent chiefdom, the Pohoy or Capaloey, centered on Hillsborough Bay near today's downtown Tampa and port, possibly extending to the Hillsborough River.[3]

These small coastal villages contained a temple mound, a central plaza, and one or more shell middens, which were trash heaps from which much archeological information has been obtained.[4][5] These mounds and middens survived long after their builders were gone. However, the vast majority (including one at the mouth of the Hillsborough River near the present site of the Tampa Convention Center) were leveled and/or used for road fill as Tampa and surrounding communities grew in the 20th century.[6][7]

European exploration

Spanish expeditions

In April 1528, the ill-fated Narváez Expedition landed near present-day Tampa with the intention of starting a colony. After being told by the natives of wealthier cultures to the north, they abandoned their camp after only a week to begin a long but futile search for non-existent riches. A dozen years later, a surviving member of the expedition named Juan Ortiz was rescued by Hernando de Soto's expedition.[8]

De Soto conducted a peace treaty with the Tocobaga, and a short-lived Spanish outpost was established. However, this was abandoned when it became clear that there was no gold in the area, that the local Indians were not interested in converting to Catholicism, and that they were too skilled as warriors to easily conquer.

Though they successfully avoided being conquered by guns, the indigenous peoples had little defense against germs. Diseases introduced by European contact would decimate the native population in the ensuing decades,[9] leading to the near-total collapse of every established culture across peninsular Florida. Between this depopulation and the indifference of its colonial owners, the Tampa Bay area would be virtually uninhabited for the next 200+ years.

English rule

Great Britain acquired Florida in 1763 as part of the treaty which ended the French and Indian War (Seven Years' War). The bay was rechristened "Hillsborough Bay" after Lord Hillsborough, the then-Secretary of State for the Colonies. Though the name "Tampa Bay" was later restored, the English period is still reflected in the names of Tampa's largest river and home county. Like Spain, Britain was much more concerned with the strategically important Atlantic coast of Florida (especially St. Augustine) than other parts of the territory and did not attempt to found settlements along the Gulf coast.

However, the Tampa Bay area did have a few residents: Cuban and Native American fishermen who lived in a seasonal encampment at the mouth of Spanish Town Creek, a freshwater stream that once ran through today's Hyde Park neighborhood to Bayshore Boulevard.[10][11] A handful of these people may have stayed year round, but the majority spent a few months catching and smoking fish (especially mullet) from the teeming waters of the bay, then returned to sell them in Cuba.[12]

Spain regained control of Florida in 1783 as part of the Treaty of Paris at the end of the American Revolution. Once again, the Florida's Gulf Coast was not a vital concern to its European owner.

Florida becomes a US territory

Since the mid-1700s, people from various native cultures (especially Creeks from Georgia) had fled to largely uninhabited Florida to distance themselves from encroaching settlers in their homelands. They were joined by escaped slaves from neighboring colonies / states, and these disparate refugees developed a new Seminole culture.

In 1821, the United States purchased Florida from Spain, mainly to end (alleged) cross-frontier Indians raids and to eliminate the southern refuge for slaves. In fact, one of the first U.S. actions in its new territory was to launch a raid which destroyed Angola, a village built by escaped slaves on the eastern shore of Tampa Bay.[13][14]

Fort Brooke: Birth of a pioneer town

In 1823, the United States imposed upon the leaders of the Seminoles to sign the Treaty of Moultrie Creek, which created a large Indian reservation in the interior of peninsular Florida. The U.S. government then built a series of forts and trading posts throughout the territory to enforce the provisions of the treaty.[15]

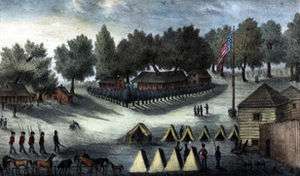

As part of this effort, Fort Brooke was established on January 10, 1824 by Colonels George Mercer Brooke and James Gadsden at the mouth of the Hillsborough River on Tampa Bay, just about where today's Tampa Convention Center sits in Downtown Tampa. The site was marked by a huge hickory tree set atop an ancient Indian mound most likely built by the Tocobaga culture centuries before. Colonel Brooke, the outpost's first commander, directed his troops to clear the area for the construction of a wooden fort and support buildings, but ordered that several ancient live oak trees inside the encampment be spared to provide shade and cheer.[16] On January 22, 1824, the post was officially named Fort Brooke.[17]

A few settlers established homesteads near the palisade, but growth was very slow due to difficult pioneer conditions and the constant fear of attack from the Seminole population, some of whom lived nearby in an uneasy truce. In December 1835, troops led by Major Francis L. Dade were ambushed by on their way from Fort Brooke to Fort King (near present-day Ocala) in a rout that was dubbed the Dade Massacre. The Second Seminole War had begun.

During the war, Fort Brooke first served as a refuge for settlers, then as a vital military depot and staging area. After almost seven years of vicious fighting, the war was over and the Seminoles were forced away from the Tampa region, and the tiny village began a period of slow growth.

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 974 | — | |

| 1870 | 796 | — | |

| 1880 | 720 | −9.5% | |

| 1890 | 5,532 | 668.3% | |

| 1900 | 15,839 | 186.3% | |

| 1910 | 37,782 | 138.5% | |

| 1920 | 51,608 | 36.6% | |

| 1930 | 101,161 | 96.0% | |

| 1940 | 108,391 | 7.1% | |

| 1950 | 124,681 | 15.0% | |

| 1960 | 274,970 | 120.5% | |

| 1970 | 277,714 | 1.0% | |

| 1980 | 271,523 | −2.2% | |

| 1990 | 280,015 | 3.1% | |

| 2000 | 303,447 | 8.4% | |

| 2010 | 335,709 | 10.6% | |

| source:[18][19][20] | |||

Incorporation and early township

A strong hurricane in late September 1848 almost washed away the budding growth. Every building in Tampa was either damaged or destroyed, including most of Fort Brooke. Much of the population stayed to rebuild, and some desperate lobbying in Washington, DC persuaded the US Army to reconsider a plan to abandon the fort and its garrison of troops.[16]

The Territory of Florida had grown enough by 1845 to become the 27th state. The settlement of Tampa recovered enough by 1849 to incorporate as the "Village of Tampa", which officially occurred on January 18. At the time, Tampa was home to 185 inhabitants, excluding military personnel stationed at Fort Brooke. The city's first official census count in 1850 listed Tampa-Fort Brooke as having 974 residents.[21] Tampa was reincorporated as a town on December 15, 1855, and Judge Joseph B. Lancaster became the first Mayor in 1856.[22][23]

Evidence of the young community's growth was seen as its first churches appeared. Tampa's first church was established by a Methodist congregation in 1846. That downtown church, First United Methodist Church of Tampa, remained open until 2011.[24] The Methodists were followed by the Baptists, who organized the First Baptist Church of Tampa in 1859,[25] and the Catholics, who founded a parish in Tampa the following year.[26]

Tampa in the Civil War and aftermath

On January 10, 1861, the state of Florida seceded from the United States along with the rest of the American South to form the Confederate States of America, touching off the American Civil War. Fort Brooke was soon manned by Confederate troops and martial law was declared in Tampa in January 1862. Tampa's city government ceased to operate for the duration of the war.[27]

Blockade and blockade runners

In late 1861, the Union navy set up a blockade near the mouth of Tampa Bay as part of the overall Anaconda Plan, which sought to squeeze the Confederacy off from outside sources of money and supplies. However, several local blockade runners consistently slipped out undetected to the Gulf of Mexico. Most notable (though not most successful) among these was former Tampa mayor James McKay Sr., who delivered Florida cattle and citrus to Spanish Cuba in exchange for gold and supplies before being captured and imprisoned by Union forces.[28] (McKay Bay, the portion of Tampa Bay adjoining the port, is named in his honor.)

Trying to put a stop to this, Union gunboats sailed up Tampa Bay to bombard Fort Brooke under the command of Captain John William Pearson and the surrounding city of Tampa. The Battle of Tampa on June 30-July 1, 1862 was inconclusive, as the shells fell ineffectually and there were no casualties on either side.[29][30]

Much more damaging to the Confederate cause was the Battle of Fort Brooke on October 17–18, 1863. The Union gunboats U.S.S. Adela and U.S.S. Tahoma came up the bay and, after firing at the fort, landed troops near the town. The Union forces headed a few miles up the Hillsborough River until they found the hidden blockade runners Scottish Chief and Kate Dale near present-day Lowry Park Zoo and burned them at their moorings.[31] The local militia was mustered to intercept the Union troops, but the raiders were able to return to their ships after a short skirmish and headed back out to sea.

The War winds down

In May 1864, the Adela returned, bringing Union forces to occupy Fort Brooke and Tampa itself. Not finding enough justification to stay, they threw most of the fort's armaments into the Hillsborough River, took much of the city's remaining food and supplies, and left after three days.[31][32]

The war ended in Confederate defeat the following spring, 1865. In May, federal troops arrived in Tampa to occupy the fort and the town as part of Reconstruction. They would remain until August, 1869.[31]

Hard times

The years after the Civil War were difficult ones in Tampa. With much of the town in disrepair and the population depleted, the isolated village faced a difficult period. As one returning soldier wrote, "Tampa was a hard-looking place. Streets and lots were grown up with weeds and the outlook certainly was not very encouraging.".[33]

As farms and ranches in the interior recovered, Tampa's small port resumed shipping Florida cattle, oranges, and other produce, primarily to New Orleans, Key West, and Cuba. However, with little industry and land transportation links limited to sandy wagon roads from the east coast of Florida, Tampa's post-war development was glacial and halting.

One factor limiting economic growth was the lack of population growth. Yellow fever had always been a threat in early Tampa, but the disease hit with terrifying regularity throughout the late 1860s and 1870s. Borne by mosquitoes from the surrounding swampland, Tampa was hit by wave after wave of yellow fever epidemics and scares throughout the period.[34] The disease was little understood at the time, and some residents simply packed up and left rather than face the mysterious and deadly peril.

The after-effects of the Civil War, disease, and disinterest put Tampa into a slow downward spiral. Conditions in the city deteriorated to the point that residents voted to temporarily disincorporate the city in 1869.[35] However, it would reincorporate in 1872. As a result, Tampa's population fell from approximately 885 in 1861[36] to 796 in 1870 and 720 in 1880.

Another blow was to come. Fort Brooke, the seed from which Tampa had germinated, had served its purpose and was decommissioned in 1883. Except for two cannons fished from the river and displayed on the nearby University of Tampa campus, all traces of the fort are gone. (Though in an odd nod to history, a large downtown parking garage near the old fort site is called the Fort Brooke Parking Garage.[37])

Despite all the hardships, or perhaps in response to them, new church denominations came to Tampa, including St. Andrew's Episcopal in 1871,[38] First Presbyterian in 1884,[39] and Zion Lutheran in 1893.[40] Additionally, Tampa’s first synagogue, Schaarai Zedek, was founded by the city’s Jewish citizenry in 1894.[41]

Rapid growth

Phosphate discovered

Phosphate, a mineral used to make fertilizers and other products, was discovered in the Bone Valley region southeast of Tampa in 1883. Soon, the mining and shipping of phosphate became important area industries. Tampa's port still ships millions of tons of phosphate annually, and the area is known as the "phosphate capital of the world."[42]

Henry Plant's railroad system

After decades of efforts by local leaders to connect the area to the United States' rapidly growing railroad network, Tampa's long-standing overland transportation problem was finally remedied in February 1884, when Henry B. Plant ran a railroad line west across central Florida to connect the Tampa Bay area to his railroad network. The railroad enabled phosphate and commercial fishing exports to go north,[43] brought many new products into the Tampa market, and started the first real tourist industry: visitors coming in modest numbers to Henry Plant's first Tampa-area hotels.

Plant continued his rail line across Tampa to the western side of the Tampa Peninsula, where he built the new town of Port Tampa City on Old Tampa Bay. There, he constructed the St. Elmo Inn and Port Tampa Inn for a hoped-for influx of visitors. The Port Tampa Inn was larger and had the distinction of being constructed directly on the bay on stilts.[44] Both of these early hotels are long gone, and the independent town of Port Tampa was annexed into Tampa in 1961.[44]

The Tampa Bay Hotel

In 1891, Henry B. Plant built a lavish 500+ room, quarter-mile long luxury resort hotel called the Tampa Bay Hotel among 150 acres (0.6 km2) of manicured gardens on the west bank of the Hillsborough River across from today's downtown. Designed by J.A. Wood, the eclectic Moorish Revival structure cost $2.5 million to build, a huge sum for the time.

Plant went on an extensive European tour while the resort was being built and sent back exotic art collectables from around the world to display at his "playground". The structure also boasted the first electric lights in Tampa and the first elevator in Florida.[45]

Heavy promotion in the Northeast US helped the Tampa Bay Hotel attract steady business for a few years, and the huge resort was finally filled to capacity during the Spanish–American War (see below). But with Plant's death in 1899, the hotel's fortunes began to fade. The city of Tampa purchased the resort in 1905 and used it for community events, including the first state fair.[46] It closed for renovations in 1930 and reopened in 1933 as the University of Tampa.

Ybor City and the cigar industry

The new railroad link attracted another industry which would finally make Tampa prosper. In 1885, the Tampa Board of Trade helped broker a land deal with Vicente Martinez Ybor to move his cigar manufacturing operations to Tampa from Key West. Ybor had been attracted by Tampa's warm and humid climate, which kept tobacco fresh and workable, and its new transportation links. Close proximity (and Henry Plant's steamships) made import of fine Cuban tobacco easy by sea, and Plant's railroad made shipment of finished cigars to the rest of the US market easy by land. This relationship is acknowledged in the Seal of Tampa, which depicts Plant's steamship Mascotte, a vessel that carried thousands of immigrants and tons of tobacco to Tampa.

Since Tampa was still a small town at the time (population less than 5,000), Ybor built hundreds of small houses around his factory to accommodate the immediate influx of thousands of Cuban and Spanish cigar workers. Other cigar manufacturers soon moved in, and Ybor City (as the settlement was dubbed) quickly made Tampa a major cigar production center. Ybor City began as a separate municipality, but, seeing the potential for greatly increased tax rolls, the city of Tampa annexed the bustling community in 1886.

Starting in the late 1880s, many Italian and a few eastern European Jewish immigrants also arrived, making Tampa one of the most diverse communities in the American South. These new arrivals had difficulty breaking into the insular cigar businesses, so many opened businesses and shops that catered to the cigar workers. The majority of Italian immigrants came from Alessandria Della Rocca and Santo Stefano Quisquina, two small Sicilian towns with which Tampa still maintains strong ties.

In 1892, Scottish businessman Hugh MacFarlane founded West Tampa, a new community across the Hillsborough River that sought to attract more cigar factories and workers. By 1900, the town already had one of the largest populations in Florida, mostly Cubans involved in the cigar industry. West Tampa was annexed by Tampa in 1925.[47][48]

The ethnic diversity of the area's population required separate establishments in the era of segregation. This included churches, such as St. James Episcopal, founded in 1895 to serve the predominantly black cigar workers from The Bahamas and Cuba.[49] Other surviving segregation-era churches include Beulah Baptist Institutional Church, formed by freed slaves in 1865,[50] and St. Paul A.M.E., founded in 1870 as Tampa's first African Methodist Episcopal congregation.[51]

The Spanish–American War

Mainly because of Henry Plant's connections in the War Department, Tampa was chosen as an embarkation center for American forces heading to Cuba for the Spanish–American War. Lieutenant Colonel Teddy Roosevelt and his Rough Riders were among the 30,000 troops who waited in Tampa for the order to ship out during the summer of 1898, filling the town to bursting.[52]

Those months, while unpleasant for the troops wearing thick wool uniforms in the oppressive Florida heat, were a great boon to Tampa's growing economy. It was also the only time when Plant's Tampa Bay Hotel was full to capacity as army officers and newspaper correspondents sought out more comfortable quarters than a hot and dusty tent.[53]

The war was also very popular in Ybor City. Many of the Cuban cigar workers had long pressed for Cuba Libre – a Cuba free of Spanish colonial rule. Leaders like Jose Marti (who had been killed in earlier fighting in Cuba against Spain) had come to Tampa many times to raise money and volunteers for the cause. With the U.S. entering the war to fight against Spain, it seemed that their dreams would soon be realized.[54]

A vital period

The building of Plant's railroad and hotels, the discovery of phosphate, and the arrival of the cigar industry – all within a decade – were crucial to Tampa's future development and its very survival. The town suddenly expanded from a dying backwater village to a bustling town to a small city. Except for temporary bumps along the way, this growth has continued unabated.

The 20th century

During the first few decades of the 20th century, the cigar making industry continued to be the backbone of Tampa's economy. The factories in Ybor City and West Tampa made an enormous number of cigars—in the peak year of 1929, over 500,000,000 cigars were hand rolled in the city.[55] As the market for cigars began to wane during the Great Depression, other industries came to the fore, especially shipping and, of course, tourism.

In 1904, a local civic association of local businessmen dubbed themselves Ye Mystic Krewe of Gasparilla (named after local mythical pirate Jose Gaspar), and staged an "invasion" of the city followed by a parade. With a few exceptions, the Gasparilla Pirate Festival has been held every year since.

Tampa holds a unique distinction in the history of aviation, a status gained just ten years after the Wright Brothers first took flight in Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. On January 1, 1914, pioneering aviator Tony Jannus captained the inaugural flight of the St. Petersburg-Tampa Airboat Line, the world's first commercial passenger airline. The airline flew scheduled flights from downtown St. Petersburg, Florida, across the bay to just south of where Tampa International Airport sits today, carrying just the pilot and a single passenger in a flying boat biplane.[56] The airline's historic significance is officially recognized by the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, and its pilot is memorialized annually by the awarding of the Tony Jannus Award to individuals of outstanding achievement in scheduled commercial aviation.[57] A permanent exhibit honoring the award recipients is maintained at Tampa International Airport, which also hosts a 12.5 feet (3.8 m) painted mural from the 1930s titled, History's First Scheduled Airline Passenger Arrives in Tampa, depicting the events of New Year's Day, 1914.[58]

Bolita, corruption, and the mob

Beginning in the late 19th century, illegal bolita lotteries were very popular among the Tampa working classes, especially in Ybor City. In the early 1920s, this small-time operation was taken over by Charlie Wall. The Wall family was one of the pioneer families from early Tampa, and Charlie Wall’s family tree included many leading businessmen, mayors, and other public officials among its branches.

Wall’s operations thrived as he expanded them to include liquor distribution and speakeasies (this was the era of Prohibition) and prostitution. Other smaller organized crime groups tried to muscle in on the action, and long-simmering rivalries were kindled.

These organizations were able to operate openly because of kick-backs and bribes to key local politicians and law enforcement officials. Charlie Wall was well connected, and he used those connections to keep his businesses running and to help put down his competition. Tampa’s political elite, which had held an inconsistent but mostly ambivalent attitude toward organized crime, quietly became de facto partners.

Election controversies

From the early 1930s until the early 1950s, every municipal election was tainted by electoral abnormalities, most with alleged mob connections. The first widespread example was Tampa’s mayoral election of 1931, when over 100 people were arrested for “cheating at the polls”. Most were supporters of the winning candidate, Robert E. Lee Chancey, who his opponents claimed had close ties to Tampa’s “underworld”.[59] After the election, all of the charges were either reduced or dropped altogether. Many of those involved had been on the city payroll at the time of their arrest, and most remained there.

The situation was even more chaotic during the next election cycle in 1935. This started before election day when Tampa’s chief of police (who supported the incumbent mayor) and the Hillsborough County Sheriff (who supported the challenger) both claimed to be the proper authority to monitor the actual voting. Anticipating trouble, Florida Governor Sholtz mobilized the National Guard to prevent violence. Still, both sheriff’s officers and city police were deployed at polling places, resulting in police officers arresting sheriff’s deputies and vice versa.[59]

Despite (or perhaps because of) the large number of observers, ballot stuffing and re-voting was widespread. The day may have turned violent if not for the presence of the National Guard troops and a sideswipe from the Labor Day Hurricane of 1935, which passed just west of Tampa during the afternoon and pelted the area with torrential rains and high winds.

In the end, the Tampa Election Board determined that Chancey had easily won re-election. They had reached these results by throwing out all ballots from 29 precincts due to “fraudulent voting”. The Board may not have been the most impartial judge of the matter, however, as Chancey had appointed the members himself.[59]

New bosses

While Charlie Wall was Tampa's first major crime boss, various factions vied for control of the area in later years. Ongoing power struggles resulted in regular organized-crime related "unsolved" murders of crime-connected figures in what became known as the "Era of Blood". To protect their interests (and keep gangland killings unsolved), crime bosses regularly kept local officials – from state attorneys to top law enforcement personnel and even mayors – on the payroll.[60]

By the late 1940s, most of the area's crime organizations were under the control of Sicilian mafioso Santo Trafficante, Sr. and his faction. After his death in 1954 from cancer, control passed to his son Santo Trafficante, Jr., who established alliances with families in New York and extended his power throughout Florida and into Batista-era Cuba.[61][62]

Reforms

The era of rampant and open corruption came to a head in the early 1950s when the Kefauver hearings, Senator Estes Kefauver's traveling investigation of organized crime in America, came to town. Informants (including the retired Charlie Wall) came forward to make startling accusations of corruption throughout Tampa's power structure. The hearings were followed by misconduct trials of several local officials and the "unsolved" murders of some of the government informants (including the retired Charlie Wall).[59]

Though most of the accused persons were acquitted or given light sentences, the trials helped to motivate Tampa to end the corruption and general sense of lawlessness which had prevailed for decades. Ethics and election reforms were passed, and the link between local government and organized crime weakened.

However, major corruption was not eliminated entirely. In 1983, 3 out of the 5 members of the Hillsborough County Commission were charged with accepting bribes. Unlike earlier crooked officials, however, these three were convicted of their crimes and sentenced to federal prison. This scandal resulted in another round of ethics reforms.[63]

Growth and changes

During the Great Depression, WPA projects were underway which include Peter O. Knight Airport, near Davis Island and Drew Field (later named Tampa International Airport). During World War II, MacDill Air Field opened up for military operations.

Annexations

Through 1885, most of Tampa's small population lived within the city limits, which encompassed a small area approximately the size of today's downtown on the east bank of the Hillsborough River. The city approximately doubled in size and population when it annexed Ybor City in 1886, and the tremendous growth of the immigrant community fueled Tampa's growth in population and economic growth over the ensuing decades.

In 1925, Tampa annexed the neighboring town of West Tampa, another cigar-centric immigrant community that had been founded in 1894. This again approximately doubled the size and population of the city.

Even with these additions, Tampa remained a compact city with a land area of 19 square miles (49 km2) until the mid-1950s.[64][65][66] Its northernmost boundary was the Hillsborough River, in the northern part of the Seminole Heights neighborhood.[67]

In 1953, the city annexed over 60 square miles (160 km2) of unincorporated land, including the communities of Sulphur Springs and Palma Ceia. As a result, Tampa grew rapidly, growing by 150,289 residents during the 1950s.[68] The growth also reflected on the city's national ranking. Tampa jumped from 85th in 1950[66] to 48th in 1960,[69] its peak ranking to date. In 1961, Tampa annexed Port Tampa, a small community on the eastern tip of the Tampa peninsula which had been built in the 1880s by Henry Plant at the terminus of his railroad line.

Most of the land added to Tampa over the years was unincorporated. Five incorporated municipalities have been consolidated into Tampa: North Tampa (1885),[70] Ybor City (1885),[70] Fort Brooke (1907),[70] West Tampa (1925),[70] and Port Tampa City (1961).[70]

University of South Florida

The University of South Florida was established in 1956, sparking development in northern Tampa and nearby Temple Terrace. Busch Gardens theme park opened in 1959.

Urban renewal and suburbanization

Suburban growth hollowed Downtown Tampa as business deteriorated. Many industries began to move to outlying areas. In the midst of this, a race riot hit the city on June 11, 1967.[71] The combination of the decline of the cigar industry and the construction of Interstates 4 and 275 further deteriorated historic areas such as Ybor City and West Tampa.[47][72] During this period the Park Tower (opened in 1973) was the city's only substantial skyscraper (460 feet/36 stories) constructed until the building boom of the 1980s. Urban renewal programs were also on the horizon.

Population growth reflected Tampa's changing fortunes. It grew very slowly in the 1960s to reach 277,714 in 1970. However, further problems in the 1970s lead to the first decline of the city's population in a century, falling to 271,523 in 1980. Tampa's national ranking dropped from 50th in 1970[73] to 53rd in 1980.[73] In contrast, suburban areas such as Brandon, Carrollwood, and other areas of Hillsborough County experienced rapid growth.

Four attempts to consolidate Tampa with Hillsborough County (1967, 1970, 1971, and 1972) all failed at the ballot box. The biggest margin was 33,160 for and 73,568 against the proposed charter in 1972.[74]

New Tampa annexation

A big expansion in the size of city came with the development of New Tampa, annexed in 1988. The addition added a 24-square mile (mostly rural) area between I-275 and I-75, increasing the city's total land area from 84 square miles (218 km2)[73] to nearly 109.[75] Despite this, the city only grew three percent in the 1980s to reach 280,015 in 1990.

Early 21st century

On January 5, 2002, just four months after the September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks, 15-year-old amateur pilot Charles Bishop flew a Cessna plane into the 42-story Bank of America Plaza building in downtown Tampa. Bishop died, but there were no other injuries (because the crash occurred on a Saturday, when few people were in the building). A suicide note found in the wreckage expressed support for Osama bin Laden. Bishop had been taking a prescription medicine for acne called Accutane that may have had the side effect of depression or severe psychosis. His family later sued Hoffman-La Roche, the company that makes Accutane, for $70 million; however, an autopsy found no traces of the drug in the teenager's system.

Stormy weather

The 2004 Atlantic Hurricane Season was historically busy for all of Florida, including Tampa. Tampa was affected by a record four hurricanes that year; Frances, Jeanne, Charley, and to a lesser extent, Ivan.

The eyes of both Jeanne and Frances passed within a few miles of Tampa as they slashed their way across the state from the east coast. Charley was forecast to make a direct hit on Tampa Bay from the south (the worst-case scenario for local flooding). But the storm made a sudden and unexpected turn to the northeast and brought only tropical storm force winds to Tampa, devastating the Ft. Myers/Port Charlotte area instead. Ivan roared past the Florida gulf coast on its way to landfall near the Alabama/Florida border, passing near enough to bring high seas and stormy conditions to the Tampa area.

Downtown revitalization

Former Tampa mayor Pam Iorio made the redevelopment of Tampa's downtown a priority and focused on bringing residents into the decidedly non-residential area.[76] Several residential and mixed-development high-rises were planned and constructed. Another of Mayor Iorio's initiatives was the Tampa Riverwalk. The development plan expanded use of the land along the Hillsborough River in downtown, where Tampa was first established. Several museums are part of the plan, including the Tampa Bay History Center, the Tampa Children's Museum, the Tampa Museum of Art[77] and the Florida Museum of Photographic Arts. Tampa Mayor Bob Buckhorn has continued the development and redevelopment focused work.

See also

Other articles which contain relevant history sections.

- History of Florida

- History of Ybor City

- Mayors of Tampa, Florida

- History of Brandon

- Hillsborough County Sheriff's Office

Articles on specific events in Tampa history

- Great Gale of 1848

- Battle of Fort Brooke

- Battle of Ballast Point

- Battle of Tampa

- Tampa Bay Hurricane of 1921

- 2002 Tampa plane crash

- Oaklawn Cemetery

Other articles of interest

- Timeline of Tampa, Florida

- Tampa-Fort Brooke, a single census unit recorded by the U.S. Census Bureau in 1850.

References

- ↑ Stewart, pg. 231.

- ↑ Milanich, Jerald T. 1995. Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1360-7 p. 40

- ↑ Milanich 1989: 299

Milanich 1995: 28, 73

Milanich 1998: 103-04, 110 - ↑ Bullen, Ripley P. (1978). "Tocobaga Indians and the Safety Harbor Culture". In Milanich and Procter.

- ↑ Milanich, Jerald T. (1998). Florida's Indians from Ancient Times to the Present. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1599-5

- ↑ Brown, Canter (1999). Tampa before the Civil War. Tampa: University of Tampa Press. ISBN 1-879852-64-0.

- ↑ Perry, Mac (1998). Indian Mounds You Can Visit: 165 Aboriginal Sites on Florida's West Coast. St. Petersburg, Fl: Great Outdoors Publishing. ISBN 0-8200-1039-1.

- ↑ Floripedia "De Soto, Hernando" - URL retrieved January 30, 2007

- ↑ Hann, John H. (2003). Indians of Central and South Florida: 1513-1763. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2645-8

- ↑ "ABOUT TAMPA BAY - PINELLAS COUNTY HISTORY - WEBCOAST PAGE TAMPA BAY TAMPA FLORIDA". www.webcoast.com. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ "ABOUT TAMPA BAY - PINELLAS COUNTY HISTORY - WEBCOAST PAGE TAMPA BAY TAMPA FLORIDA". www.webcoast.com. Retrieved 2008-02-24.

- ↑ Thomas Angarano (1915-05-27). "About Tampa Bay - Pinellas County History". Webcoast.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Excavators seeking freedom pioneers - St. Pete Times". Sptimes.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Looking for Angola". Looking for Angola. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ http://fcit.usf.edu/florida/lessons/sem_war/sem_war1.htm

- 1 2 Brown, Cantor. Tampa Before the Civil War. University of Tampa Press. 1-879852-64-0

- ↑ museumofcigars.com. "fort brooke". Museumofcigars.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "CENSUS OF POPULATION AND HOUSING (1790-2000)". U.S. Census Bureau. Retrieved 2011-04-11.

- ↑ 1850 census population included Fort Brooke, which was located outside the municipal limits.

- ↑ Not returned separately by enumerators in 1860.

- ↑ http://www2.census.gov/prod2/decennial/documents/1850c-11.pdf

- ↑ Archived January 29, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ City of Tampa Incorporation History Archived February 12, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ “Tampa's Oldest Church, First United Methodist, Will Close”. Tampa Bay Times.. Retrieved August 7, 2015.

- ↑ “About Us”. First Baptist Church of Tampa.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ “Sacred Heart Parish History”. Sacred Heart Catholic Church.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Military Rule of Tampa During Civil War". Tampagov.net. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "James McKay, Sr. – 6th Mayor of Tampa". Tampagov.net. Archived from the original on December 21, 2009. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Florida Civil War Battle Tampa Bay American War Between the States". Americancivilwar.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Battle Summary: Tampa, FL". Cr.nps.gov. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- 1 2 3 "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-08-15.

- ↑ Pizzo 1968

- ↑ Pizzo 1968, p. 71

- ↑ "Edward A. Clarke – 10th Mayor of Tampa". Tampagov.net. Archived from the original on January 15, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ http://www.tampagov.net/dept_City_Clerk/previous_mayors/john_henderson.asp. Retrieved February 6, 2007. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - ↑ http://purl.fcla.edu/fcla/etd/SFE0000077

- ↑ "Fort Brooke Garage". Tampagov.net. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ “St. Andrew’s Episcopal Church”. The Historical Marker Database.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ “About Us”. Archived January 15, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. First Presbyterian Church of Tampa.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ “About Us”. Zion Evangelical Lutheran Church.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ “Our History”. Archived September 11, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Congregation Schaarai Zedek.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ Tampa Port Authority Archived August 9, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "About Bone Valley". Baysoundings.com. Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- 1 2 "Port_Tampa_City_Yesteryear". Porttampa.org. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Henry B. Plant Museum - The History". Plantmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- 1 2 Garcia, Wayne. "Creative Loafing Tampa | News | The Western Front". Tampa.creativeloafing.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-02-27. Retrieved 2007-02-06.

- ↑ “Our History”. Archived January 18, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. St. James House of Prayer.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ “History”. Beulah Baptist Institutional Church.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ “Tampa - Florida’s Industrial Port City”. Archived October 21, 2010, at the Wayback Machine. Florida History Internet Center.. Retrieved February 27, 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 2007-08-09. Retrieved 2007-08-13.

- ↑ "Henry B. Plant Museum - Spanish-American War". Plantmuseum.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Jose Marti". Cigar City Magazine. 2007-03-13. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ Ybor City: The Making of a Landmark Town by Frank Lastra

- ↑ "Tony Jannus, An Enduring Legacy of Aviation". The Tony Jannus Distinguished Aviation Society.. Retrieved February 23, 2010. Archived July 20, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Take Flight", December 2009. The Tony Jannus Distinguished Aviation Society. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- ↑ Bennett, Lennie, October 13, 2002. "A legacy takes flight", St. Petersburg Times.. Retrieved February 23, 2010.

- 1 2 3 4 Kerstein, Robert (2001). Politics and Growth in 20th Century Tampa. University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2083-2.

- ↑ Deitche, Scott. "Creative Loafing Tampa | News | Cover | The Mob". Tampa.creativeloafing.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ Deitche, Scott. "Creative Loafing Tampa". Weeklyplanet.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Feature Articles 101". AmericanMafia.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ Deeson, Mike (1983-02-01). "Public Corruption Arrests 25 years later". Tampabays10.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ 1930 U.S. Census

- ↑ 1940 U.S. Census

- 1 2 1950 U.S. Census

- ↑ census.gov

- ↑ previous city council members Archived September 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine. tampagov.net (access date=February 6, 2007) (dead link date=May 2016)

- ↑ 1960 U.S. Census

- 1 2 3 4 5 Ben Cahoon. "Mayors of U.S. Cities M-W". Worldstatesmen.org. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Nation: How to Cool It". Time. June 30, 1967. Retrieved May 4, 2010.

- ↑ [By Elaine C. Iles and Jo-Anne Peck]. "Services - Office of Cultural & Historical Programs". Flheritage.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- 1 2 3

- ↑ http://etd.lib.fsu.edu/theses/available/etd-04152005-170723/unrestricted/07_lsj_chapter6_c.pdf

- ↑ 1990 U.S. Census

- ↑ "Floridian: Urban culture clash". Sptimes.com. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

- ↑ "Creative Loafing Tampa | News | Downtowns On The Verge". Tampa.creativeloafing.com. Archived from the original on 2009-04-23. Retrieved 2010-05-16.

Bibliography

- Brown, Canter (1999). Tampa before the Civil War. Tampa: University of Tampa Press. ISBN 978-1-879852-64-8.

- Brown, Canter (2000). Tampa in Civil War & Reconstruction. Tampa: University of Tampa Press. ISBN 978-1-879852-68-6.

- Kerstein, Robert (2001). Politics and Growth in Twentieth-Century Tampa. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-2083-2.

- Lastra, Frank (2005). Ybor City: the Making of a Landmark Town. Tampa: University of Tampa Press. ISBN 978-1-59732-003-0.

- Long, Durward. "The Making of Modern Tampa: A City of the New South, 1885-1911." Florida Historical Quarterly 49.4 (1971): 333-345. in JSTOR

- Long, Durward. "The Historical Beginnings of Ybor City and Modern Tampa." Florida Historical Quarterly 45.1 (1966): 31-44. in JSTOR

- Long, Durward. "Labor relations in the Tampa cigar industry, 1885–1911." Labor History 12.4 (1971): 551-559.

- Milanich, Jerald (1995). Florida Indians and the Invasion from Europe. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 0-8130-1360-7.

- Mormino, Gary (1998). The Immigrant World of Ybor City. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-1630-6.

- Mormino, Gary R., and George E. Pozzetta. "Immigrant Women in Tampa: The Italian Experience, 1890-1930." Florida Historical Quarterly 61.3 (1983): 296-312. in JSTOR

- Mormino, Gary R. "Tampa's Splendid Little War: Local History and the Cuban War of Independence" OAH Magazine of History 12#3 (1998), pp. 37-42 in JSTOR

- Pérez, Louis A. "Cubans in Tampa: From Exiles to Immigrants, 1892-1901." Florida Historical Quarterly 57.2 (1978): 129-140. in JSTOR

- Pizzo, Anthony (1968). Tampa Town 1824-1886: Cracker Village with a Latin Accent. Tampa, Fl: Hurricane House.

- Pizzo, Anthony (1983). Tampa the Treasure City. Tulsa, OK: Continental Heritage Press. ISBN 978-0-932986-38-2.

- Stewart, George (2008). Names on the Land: a Historical Account of Place-Naming in the United States. New York: NYRB Classics. ISBN 978-1-59017-273-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to History of Tampa. |

- Tampa Bay History Center

- Tampa, Florida, by the Jewish Virtual Library

- Tampa Bay History Collection, includes historical photographs (University of South Florida)