Talin protein

| Talin, middle domain | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | Talin_middle | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF09141 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR015224 | ||||||||

| SCOP | 1sj7 | ||||||||

| SUPERFAMILY | 1sj7 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| talin 1 | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | TLN1 |

| Alt. symbols | TLN |

| Entrez | 7094 |

| HUGO | 11845 |

| OMIM | 186745 |

| RefSeq | NM_006289 |

| UniProt | Q9Y490 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 9 p23-p21 |

| talin 2 | |

|---|---|

| Identifiers | |

| Symbol | TLN2 |

| Entrez | 83660 |

| HUGO | 15447 |

| OMIM | 607349 |

| RefSeq | NM_015059 |

| UniProt | Q9Y4G6 |

| Other data | |

| Locus | Chr. 15 q15-q21 |

Talin is a high-molecular-weight cytoskeletal protein concentrated at regions of cell–substratum contact[1] and, in lymphocytes, at cell–cell contacts.[2][3] Discovered in 1983 by Keith Burridge and colleagues,[1] talin is a ubiquitous cytosolic protein that is found in high concentrations in focal adhesions. It is capable of linking integrins to the actin cytoskeleton either directly or indirectly by interacting with vinculin and alpha-actinin.[4]

Also, talin-1 drives extravasation mechanism through engineered human microvasculature in microfluidic systems. Talin-1 is involved in each part of extravasation affecting adhesion, trans-endothelial migration and the invasion stages.[5]

Integrin receptors are involved in the attachment of adherent cells to the extracellular matrix[6][7] and of lymphocytes to other cells. In these situations, talin codistributes with concentrations of integrins in the plasma membrane.[8][9] Furthermore, in vitro binding studies suggest that integrins bind to talin, although with low affinity.[10] Talin also binds with high affinity to vinculin,[11] another cytoskeletal protein concentrated at points of cell adhesion.[12] Finally, talin is a substrate for the calcium-ion activated protease, calpain II,[13] which is also concentrated at points of cell–substratum contact.[14]

Protein domains

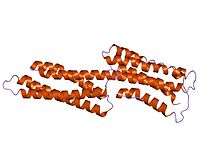

Talin consists of a large C-terminal rod domain that contains bundles of alpha helices and an N-terminal FERM (band 4.1, ezrin, radixin, and moesin) domain with three subdomains: F1, F2, and F3.[15][16][17][18] The F3 subdomain of the FERM domain contains the highest affinity integrin-binding site for integrin β tails and is sufficient to activate integrins.[19]

Middle domain

Structure

Talin also has a middle domain, which has a structure consisting of five alpha helices that fold into a bundle. It contains a vinculin binding site (VBS) composed of a hydrophobic surface spanning five turns of helix four.

Function

Activation of the VBS leads to the recruitment of vinculin to form a complex with the integrins which aids stable cell adhesion. Formation of the complex between VBS and vinculin requires prior unfolding of this middle domain: once released from the talin hydrophobic core, the VBS helix is then available to induce the 'bundle conversion' conformational change within the vinculin head domain thereby displacing the intramolecular interaction with the vinculin tail, allowing vinculin to bind actin.[17]

Talin carries mechanical force (of 7-10 piconewton) during cell adhesion. It also allows cells to measure extracellular rigidity, since cells in which talin is prevented from forming mechanical linkages can no longer distinguish whether they are on a soft or rigid surface.[20]

Vinculin binding site

| VBS | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

human vinculin head (1-258) in complex with talin's vinculin binding site 3 (residues 1944-1969) | |||||||||

| Identifiers | |||||||||

| Symbol | VBS | ||||||||

| Pfam | PF08913 | ||||||||

| InterPro | IPR015009 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Function

Vinculin binding sites are protein domains predominantly found in talin and talin-like molecules, enabling binding of vinculin to talin, stabilising integrin-mediated cell-matrix junctions. Talin, in turn, links integrins to the actin cytoskeleton.

Structure

The consensus sequence for vinculin binding sites is LxxAAxxVAxxVxxLIxxA, with a secondary structure prediction of four amphipathic helices. The hydrophobic residues that define the VBS are themselves 'masked' and are buried in the core of a series of helical bundles that make up the talin rod.[21]

Activation of the integrin αIIbβ3

A structure–function analysis reported recently[22] provides a cogent structural model (see top right) to explain talin-dependent integrin activation in three steps:

- The talin F3 domain (surface representation; colored by charge), freed from its autoinhibitory interactions in the full-length protein, becomes available for binding to the integrin.

- F3 engages the membrane-distal part of the β3-integrin tail (in red), which becomes ordered, but the α–β integrin interactions that hold the integrin in the low-affinity conformation remain intact.

- In a subsequent step, F3 engages the membrane-proximal portion of the β3 tail while maintaining its membrane–distal interactions.

Human proteins containing this domain

See also

- Actin-binding protein

- Merlin (protein) an acronym for "Moesin-Ezrin-Radixin-Like Protein"

References

- 1 2 Burridge K, Connell L (1983). "A new protein of adhesion plaques and ruffling membranes". J. Cell Biol. 97 (2): 359–67. doi:10.1083/jcb.97.2.359. PMC 2112532

. PMID 6684120.

. PMID 6684120. - ↑ Kupfer A, Singer SJ, Dennert G (1986). "On the mechanism of unidirectional killing in mixtures of two cytotoxic T lymphocytes. Unidirectional polarization of cytoplasmic organelles and the membrane-associated cytoskeleton in the effector cell". J. Exp. Med. 163 (3): 489–98. doi:10.1084/jem.163.3.489. PMC 2188060

. PMID 3081676.

. PMID 3081676. - ↑ Burn P, Kupfer A, Singer SJ (1988). "Dynamic membrane-cytoskeletal interactions: specific association of integrin and talin arises in vivo after phorbol ester treatment of peripheral blood lymphocytes". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 85 (2): 497–501. doi:10.1073/pnas.85.2.497. PMC 279577

. PMID 3124107.

. PMID 3124107. - ↑ Alan D. Michelson (2006). Platelets, Second Edition. Boston: Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-369367-5.

- ↑ Gilardi, Mara. "The key role of talin-1 in cancer cell extravasation dissected through human vascularized 3D microfluidic model". Thromb Res. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(16)30145-1.

- ↑ Hynes RO (1987). "Integrins: a family of cell surface receptors". Cell. 48 (4): 549–54. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90233-9. PMID 3028640.

- ↑ Ruoslahti E, Pierschbacher MD (1987). "New perspectives in cell adhesion: RGD and integrins". Science. 238 (4826): 491–7. doi:10.1126/science.2821619. PMID 2821619.

- ↑ Chen WT, Hasegawa E, Hasegawa T, Weinstock C, Yamada KM (1985). "Development of cell surface linkage complexes in cultured fibroblasts". J. Cell Biol. 100 (4): 1103–14. doi:10.1083/jcb.100.4.1103. PMC 2113771

. PMID 3884631.

. PMID 3884631. - ↑ Kupfer A, Singer SJ (1989). "The specific interaction of helper T cells and antigen-presenting B cells. IV. Membrane and cytoskeletal reorganizations in the bound T cell as a function of antigen dose". J. Exp. Med. 170 (5): 1697–713. doi:10.1084/jem.170.5.1697. PMC 2189515

. PMID 2530300.

. PMID 2530300. - ↑ Horwitz A, Duggan K, Buck C, Beckerle MC, Burridge K (1986). "Interaction of plasma membrane fibronectin receptor with talin—a transmembrane linkage". Nature. 320 (6062): 531–3. doi:10.1038/320531a0. PMID 2938015.

- ↑ Burridge K, Mangeat P (1984). "An interaction between vinculin and talin". Nature. 308 (5961): 744–6. doi:10.1038/308744a0. PMID 6425696.

- ↑ Geiger B (1979). "A 130K protein from chicken gizzard: its localization at the termini of microfilament bundles in cultured chicken cells". Cell. 18 (1): 193–205. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(79)90368-4. PMID 574428.

- ↑ Fox JE, Goll DE, Reynolds CC, Phillips DR (1985). "Identification of two proteins (actin-binding protein and P235) that are hydrolyzed by endogenous Ca2+-dependent protease during platelet aggregation". J. Biol. Chem. 260 (2): 1060–6. PMID 2981831.

- ↑ Beckerle MC, Burridge K, DeMartino GN, Croall DE (1987). "Colocalization of calcium-dependent protease II and one of its substrates at sites of cell adhesion". Cell. 51 (4): 569–77. doi:10.1016/0092-8674(87)90126-7. PMID 2824061.

- ↑ Chishti AH, Kim AC, Marfatia SM, Lutchman M, Hanspal M, Jindal H, Liu SC, Low PS, Rouleau GA, Mohandas N, Chasis JA, Conboy JG, Gascard P, Takakuwa Y, Huang SC, Benz EJ, Bretscher A, Fehon RG, Gusella JF, Ramesh V, Solomon F, Marchesi VT, Tsukita S, Tsukita S, Hoover KB (1998). "The FERM domain: a unique module involved in the linkage of cytoplasmic proteins to the membrane". Trends Biochem. Sci. 23 (8): 281–2. doi:10.1016/S0968-0004(98)01237-7. PMID 9757824.

- ↑ García-Alvarez B, de Pereda JM, Calderwood DA, Ulmer TS, Critchley D, Campbell ID, Ginsberg MH, Liddington RC (2003). "Structural determinants of integrin recognition by talin". Mol. Cell. 11 (1): 49–58. doi:10.1016/S1097-2765(02)00823-7. PMID 12535520.

- 1 2 Papagrigoriou E, Gingras AR, Barsukov IL, Bate N, Fillingham IJ, Patel B, Frank R, Ziegler WH, Roberts GC, Critchley DR, Emsley J (2004). "Activation of a vinculin-binding site in the talin rod involves rearrangement of a five-helix bundle". EMBO J. 23 (15): 2942–51. doi:10.1038/sj.emboj.7600285. PMC 514914

. PMID 15272303.

. PMID 15272303. - ↑ Rees DJ, Ades SE, Singer SJ, Hynes RO (1990). "Sequence and domain structure of talin". Nature. 347 (6294): 685–9. doi:10.1038/347685a0. PMID 2120593.

- ↑ Calderwood DA, Yan B, de Pereda JM, Alvarez BG, Fujioka Y, Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH (2002). "The phosphotyrosine binding-like domain of talin activates integrins". J. Biol. Chem. 277 (24): 21749–58. doi:10.1074/jbc.M111996200. PMID 11932255.

- ↑ Austen K, Ringer P, Mehlich A, Chrostek-Grashoff A, Kluger C, Klingner C, Sabass B, Zent R, Rief M, Grashoff C (2015). "Extracellular rigidity sensing by talin isoform-specific mechanical linkages". Nat. Cell Biol. 17: 1597–606. doi:10.1038/ncb3268. PMC 4662888

. PMID 26523364.

. PMID 26523364. - ↑ Gingras AR, Vogel KP, Steinhoff HJ, Ziegler WH, Patel B, Emsley J, Critchley DR, Roberts GC, Barsukov IL (February 2006). "Structural and dynamic characterization of a vinculin binding site in the talin rod". Biochemistry. 45 (6): 1805–17. doi:10.1021/bi052136l. PMID 16460027.

- ↑ Wegener KL, Partridge AW, Han J, Pickford AR, Liddington RC, Ginsberg MH, Campbell ID (2007). "Structural basis of integrin activation by talin". Cell. 128 (1): 171–82. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.10.048. PMID 17218263.

External links

- MBInfo: Talin

- MBInfo: Talin activates Integrin

- Talin-1 UniProtKB/Swiss-Prot entry Q9Y490

- Talin substrate for calpain – PMAP The Proteolysis Map animation.

- Talin-1 Info with links in the Cell Migration Gateway

- Talin-2 Info with links in the Cell Migration Gateway

- Integrins at the US National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ↑ Gilardi, Mara (Apr 2016). "The key role of talin-1 in cancer cell extravasation dissected through human vascularized 3D microfluidic model". Thromb Res: 140 Suppl 1:S180-1. doi:10.1016/S0049-3848(16)30145-1.