Robert Bloch

| Robert Bloch | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Robert Albert Bloch April 5, 1917 Chicago, Illinois |

| Died |

September 23, 1994 (aged 77) Los Angeles, California |

| Pen name | Tarleton Fiske, Will Folke, Nathan Hindin, E. K. Jarvis, Floyd Scriltch, Wilson Kane, John Sheldon, Collier Young[1] but see note under The Todd Dossier in novels. |

| Occupation | Novelist, short-story writer |

| Nationality | American |

| Period | 1934–1994 |

| Genre | Crime, Fantasy, Horror, Science fiction |

| Notable works | Psycho, Psycho II, Psycho House, American Gothic, Firebug |

| Spouse |

Marion Ruth Holcombe (1940–63; divorced; 1 child) Eleanor Zalisko Alexander (1964–94; his death) |

Robert Albert Bloch (/blɑːk/; April 5, 1917 – September 23, 1994) was an American fiction writer, primarily of crime, horror, fantasy and science fiction, from Milwaukee, Wisconsin. He is best known as the writer of Psycho, the basis for the film of the same name by Alfred Hitchcock. His fondness for a pun is evident in the titles of his story collections such as Tales in a Jugular Vein, Such Stuff as Screams Are Made Of and Out of the Mouths of Graves.

Bloch wrote hundreds of short stories and over 30 novels. He was one of the youngest members of the Lovecraft Circle. H. P. Lovecraft was Bloch's mentor and one of the first to seriously encourage his talent. However, while Bloch started his career by emulating Lovecraft and his brand of "cosmic horror", he later specialized in crime and horror stories dealing with a more psychological approach.

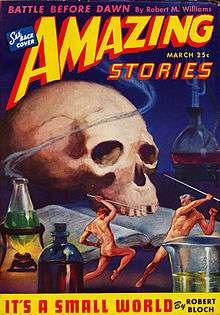

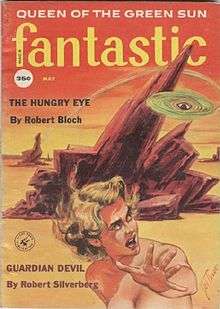

Bloch was a contributor to pulp magazines such as Weird Tales in his early career, and was also a prolific screenwriter and a major contributor to science fiction fanzines and fandom in general.

He won the Hugo Award (for his story "That Hell-Bound Train"), the Bram Stoker Award, and the World Fantasy Award. He served a term as president of the Mystery Writers of America (1970) and was a member of that organisation and of Science Fiction Writers of America, the Writers Guild of America, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences and the Count Dracula Society. In 2008, The Library of America selected Bloch's essay "The Shambles of Ed Gein" (1962)[2] for inclusion in its two-century retrospective of American true crime.[3]

His favorites among his own novels were The Kidnapper, The Star Stalker, Psycho, Night-World, and Strange Eons.[4] His work has been extensively adapted for the movies and television, comics and audio books.

Biography

Youth and education

Bloch was born in Chicago, the son of Raphael "Ray" Bloch (1884–1952), a bank cashier, and his wife Stella Loeb (1880–1944), a social worker, both of German Jewish descent. Bloch's family moved to Maywood, a Chicago suburb, when he was five. He attended the Methodist Church there, despite his parents' Jewish heritage. At ten years of age, living in Maywood, he attended a screening of Lon Chaney, Sr.'s film The Phantom of the Opera (1925) late at night on his own. The scene of Chaney removing his mask terrified the young Bloch and sparked his interest in horror.[5]

In 1929 Ray Bloch lost his bank job, and the family moved to Milwaukee, where Stella worked at the Milwaukee Jewish Settlement settlement house. Robert attended Washington, then Lincoln High School, where he met lifelong friend Harold Gauer. Gauer was editor of The Quill, Lincoln's literary magazine, and accepted Bloch's first published short story, a horror story titled "The Thing" (the "thing" of the title was Death). Both Bloch and Gauer graduated from Lincoln in 1934[5] during the height of the Great Depression. Bloch was involved in the drama department at Lincoln and wrote and performed in school vaudeville skits.

Weird Tales and the Influence of H.P. Lovecraft

During the 1930s, Bloch was an avid reader of the pulp magazine Weird Tales, which he had discovered at the age of ten in 1927; he began his readings of the magazine with the first instalment of Otis Adelbert Kline's "The Bride of Osiris" which dealt with a secret Egyptian city called Karneter located beneath Bloch's birth city of Chicago.[6] H. P. Lovecraft, a frequent contributor to Weird Tales became one of his favorite writers. As a teenager, Bloch wrote a fan letter to Lovecraft (1933), who gave him advice on his own fiction-writing efforts.[7] Bloch's first publication was with the short story "Lilies" in the semi-professional magazine Marvel Tales (Winter 1934). Bloch began correspondence with August Derleth, Clark Ashton Smith and others of the 'Lovecraft Circle'. Bloch's first publication in Weird Tales was in its letter-column, with a letter criticising the Conan stories of Robert E. Howard. His first professional sales, at the age of 17 (July 1934), to Weird Tales, were the short stories "The Feast in the Abbey" and "The Secret in the Tomb". "Feast..." appeared first, in the January 1935 issues[8] which actually went on sale November 1, 1934; "Secret in the Tomb" appeared in the May 1935 Weird Tales.[9]

Bloch's early stories were strongly influenced by Lovecraft. Indeed, a number of his stories were set in, and extended, the world of Lovecraft's Cthulhu Mythos. These include "The Dark Demon", in which the character Gordon is a figuration of Lovecraft, and which features Nyarlathotep; "The Faceless God" (features Nyarlathotep); "The Grinning Ghoul" (written after the manner of Lovecraft) and "The Unspeakable Betrothal" (vaguely attached to the Cthulhu Mythos). It was Bloch who invented, for example, the oft-cited Mythos texts De Vermis Mysteriis and Cultes des Goules. Many other stories influenced by Lovecraft were later collected in Bloch's volume Mysteries of the Worm (now in its third, expanded edition). In 1935 Bloch wrote the tale "Satan's Servants", on which Lovecraft lent much advice, but none of the prose was by Lovecraft; this tale did not appear in print until 1949, in Something About Cats and Other Pieces.

The young Bloch appears, thinly disguised, as the character "Robert Blake" in Lovecraft's story "The Haunter of the Dark" (1936), which is dedicated to Bloch. Bloch was the only individual to whom Lovecraft ever dedicated a story. In this story, Lovecraft kills off the Bloch character, repaying a courtesy Bloch earlier paid Lovecraft with his 1935 tale "The Shambler from the Stars", in which the Lovecraft-inspired figure dies; the story goes so far as to use Bloch's then-current street address in Milwaukee.[10] (Bloch even had a signed certificate from Lovecraft [and some of his creations] giving Bloch permission to kill Lovecraft off in a story.) Bloch later wrote a third tale, "The Shadow From the Steeple", picking up where "The Haunter of the Dark" finished (Weird Tales Sept 1950). After Lovecraft's death in 1937, Bloch continued writing for Weird Tales, where he became one of its most popular authors. He also began contributing to other pulps, such as the science fiction magazine Amazing Stories.

Bloch's late novel Strange Eons is a full-length tribute to the style and subject matter of Lovecraft.

After Lovecraft's death in 1937, which affected Bloch deeply, Bloch broadened the scope of his fiction. His horror themes included voodoo ("Mother of Serpents"), the conte cruel ("The Mandarin's Canaries"), demonic possession ("Fiddler's Fee"), and black magic ("Return to the Sabbat"). Bloch visited Henry Kuttner in California in 1937. Bloch's first science fiction story, "The Secret of the Observatory", was published in Amazing Stories (August 1938).

Milwaukee Fictioneers and the Depression

In 1935 Bloch joined a writers' group, The Milwaukee Fictioneers, members of which included Stanley Weinbaum, Ralph Milne Farley and Raymond A. Palmer. Another member of the group was Gustav Marx, who offered Bloch a job writing copy in his advertising firm, also allowing Bloch to write stories in his spare time in the office. Bloch was close friends with C.L. Moore and her husband Henry Kuttner, who visited him in Milwaukee.

During the years of the Depression, Bloch appeared regularly in dramatic productions, writing and performing in his own sketches. Around 1936 he sold some gags to radio comedians Stoopnagle and Budd, and to Roy Atwell.

In an Amazing Stories profile in 1938, accompanying his first published science fiction story, Bloch described himself as "tall, dark, unhandsome" with "all the charm and personality of a swamp adder". He noted that "I hate everything", but reserved particular dislike for "bean soup, red nail polish, house-cleaning, and optimists".[11]

Campaign manager for Carl Zeidler

In 1939, Bloch was contacted by James Doolittle, who was managing the campaign for a little-known assistant city attorney in Milwaukee, Wisconsin named Carl Zeidler. He was asked to work on his speechwriting, advertising, and photo ops, in collaboration with Harold Gauer. They created elaborate campaign shows; in Bloch's 1993 autobiography, Once Around the Bloch, he gives an inside account of the campaign, and the innovations he and Gauer came up with – for instance, the original releasing-balloons-from-the-ceiling shtick. He comments bitterly on how, after Zeidler's victory, they were ignored and not even paid their promised salaries. He ends the story with a wryly philosophical point:

If Carl Zeidler had not asked Jim Doolittle to manage his campaign, Doolittle would never have contacted me about it. And the only reason Doolittle knew me to begin with was because he read my yarn ("The Cloak") in Unknown. Rattling this chain of circumstances, one may stretch it a bit further. If I had not written a little vampire story called "The Cloak", Carl Zeidler might never have become mayor of Milwaukee.

1940s and 1950s

In the 1940s, Bloch created the humorous series character Lefty Feep in a story for Fantastic Adventures. He published a total of 23 Lefty Feep stories, the last one published in 1950, but the bulk appeared during World War II. Feep's character name had actually been coined by Bloch's friend/collaborator Harold Gauer for their unpublished novel In the Land of Sky-Blue Ointments,[12] Bloch also worked for a time in local vaudeville and tried to break into writing for nationally known performers.

In 1944 Bloch was asked to write 39 15-minute episodes of a radio horror show called Stay Tuned for Terror. Many of the programs were adaptations of his own pulp stories. None of the episodes, which were all broadcast, are extant.[13]

A year later August Derleth's Arkham House, Lovecraft's publisher, published Bloch's first collection of short stories, The Opener of the Way. At the same time, his best-known early tale, "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper", received considerable attention through dramatization on radio and reprinting in anthologies. This story, as noted below, involving a Ripper who has found literal immortality through his crimes, has been widely imitated (or plagiarized); Bloch himself would return to the theme (see below).

Bloch gradually evolved away from Lovecraftian imitations towards a unique style of his own. One of the first distinctly "Blochian" stories was "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper", which was published in Weird Tales in 1943. The story was Bloch's take on the Jack the Ripper legend, and was filled out with more genuine factual details of the case than many other fictional treatments.[14] It cast the Ripper as an eternal being who must make human sacrifices to extend his immortality.[15] It was adapted for both radio (in Stay Tuned for Terror) and television (as an episode of Thriller in 1961 adapted by Barré Lyndon).[16] Bloch followed up this story with a number of others in a similar vein dealing with half-historic, half-legendary figures such as the Man in the Iron Mask ("Iron Mask", 1944), the Marquis de Sade ("The Skull of the Marquis de Sade", 1945) and Lizzie Borden ("Lizzie Borden Took an Axe...", 1946).

Bloch's first novel was the thriller The Scarf (1947; he later issued a revised edition in 1966). It tells the story of a writer, Daniel Morley, who uses real women as models for his characters. But as soon as he is done writing the story, he is compelled to murder them, and always the same way: with the maroon scarf he has had since childhood. The story begins in Minneapolis and follows him and his trail of dead bodies to Chicago, New York, and finally Hollywood, where his hit novel is going to be turned into a movie, and where his self-control may have reached its limit.

Bloch published three novels in 1954 – Spiderweb, The Kidnapper and The Will to Kill as he endeavored to support his family. That same year he was a weekly guest panellist on the TV quiz show It's a Draw. Shooting Star (1958), a mainstream novel, was published in a double volume with a collection of Bloch's stories titled Terror in the Night. This Crowded Earth (1958) was science fiction.

With the demise of Weird Tales, Bloch continued to have his fiction published in Amazing, Fantastic, The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, and Fantastic Universe; he was a particularly frequent contributor to Imagination and Imaginative Tales. His output of thrillers increased and he began to appear regularly in The Saint, Ellery Queen and similar mystery magazines, and to such suspense and horror-fiction magazine projects as Shock.

Jack the Ripper

Bloch continued to revisit the Jack the Ripper theme. His contribution to Harlan Ellison's 1967 science fiction anthology Dangerous Visions was a story, "A Toy for Juliette", which evoked both Jack the Ripper and the Marquis de Sade in a time-travel story. The same anthology had Ellison's sequel to it titled "The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World". His earlier idea of the Ripper as an immortal being resurfaced in Bloch's contribution to the original Star Trek series episode "Wolf in the Fold". His 1984 novel Night of the Ripper is set during the reign of Queen Victoria and follows the investigation of Inspector Frederick Abberline in attempting to apprehend the Ripper, and includes some famous Victorians such as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle within the storyline.

Psycho

Bloch won the Hugo Award for Best Short Story in 1959, the same year that Psycho was published. Bloch had written an earlier short story involving split personalities, "The Real Bad Friend", which appeared in the February 1957 Mike Shayne Mystery Magazine, that foreshadowed the 1959 novel Psycho. However, Psycho also has thematic links to the story "Lucy Comes to Stay".

Norman Bates, the main character in Psycho, was very loosely based on two people. First was the real-life serial killer Ed Gein, about whom Bloch later wrote a fictionalized account, "The Shambles of Ed Gein". (The story can be found in Crimes and Punishments: The Lost Bloch, Volume 3). Second, it has been indicated by several people, including Noel Carter (wife of Lin Carter) and Chris Steinbrunner, as well as allegedly by Bloch himself, that Norman Bates was partly based on Calvin Beck, publisher of Castle of Frankenstein.[17] Bloch's basing of the character of Norman Bates on Ed Gein is discussed in the documentary Ed Gein: The Ghoul of Plainfield, which can be found on Disc 2 of the DVD release of 2003's The Texas Chainsaw Massacre. Bloch has also, however, commented that it was the situation itself - a mass murderer living undetected and unsuspected in a typical small town in middle America - rather than Gein himself who sparked Bloch's storyline. He writes: "Thus the real-life murderer was not the role model for my character Norman Bates. Ed Gein didn't own or operate a motel. Ed Gein didn't kill anyone in the shower. Ed Gein wasn't into taxidermy. Ed Gein didn't stuff his mother, keep her body in the house, dress in a drag outfit, or adopt an alternative personality. These were the functions and characteristics of Norman Bates, and Norman Bates didn't exist until I made him up. Out of my own imagination, I add, which is probably the reason so few offer to take showers with me." [18]

Though Bloch had little involvement with the film version of his novel, which was directed by Alfred Hitchcock from an adapted screenplay by Joseph Stefano, he was to become most famous as its author.

The novel is one of the first examples at full length of Bloch's use of modern urban horror relying on the horrors of interior psychology rather than the supernatural. "By the mid-1940s, I had pretty well mined the vein of ordinary supernatural themes until it had become varicose," Bloch explained to Douglas E. Winter in an interview. "I realized, as a result of what went on during World War II and of reading the more widely disseminated work in psychology, that the real horror is not in the shadows, but in that twisted little world inside our own skulls."[19] While Bloch was not the first horror writer to utilise a psychological approach (that honor belongs to Edgar Allan Poe), Bloch's psychological approach in modern times was comparatively unique.

Bloch's agent, Harry Altshuler, received a "blind bid" for the novel – the buyer's name wasn't mentioned – of $7,500 for screen rights to the book. The bid eventually went to $9,500, which Bloch accepted. Bloch had never sold a book to Hollywood before. His contract with Simon & Schuster included no bonus for a film sale. The publisher took 15 percent according to contract, while the agent took his 10%; Bloch wound up with about $6,750 before taxes. Despite the enormous profits generated by Hitchcock's film, Bloch received no further direct compensation.

Only Hitchcock's film was based on Bloch's novel. The later films in the Psycho series bear no relation to either of Bloch's sequel novels. Indeed, Bloch's proposed script for the film Psycho II was rejected by the studio (as were many other submissions), and it was this that he subsequently adapted for his own sequel novel.

The 2012 film Hitchcock tells the story of Alfred Hitchcock's making of the film version of Psycho. Although it mentions Bloch and his novel, however, Bloch himself was not a character in the movie.

The 1960s: Hollywood and screenwriting

Following his move to Hollywood, around 1960, Bloch had multiple assignments from various television companies. However, he was not allowed to write for five months when the Writers Guild had a strike. After the strike was over, he became a much used scriptwriter in television and film projects in the mystery, suspense, and horror genre. His first assignments were for the Macdonald Carey vehicle, Lock-Up, (penning five episodes) as well as one for Whispering Smith, and an original screenplay for the 1962 film The Couch. Further TV work included an episode of Bus Stop, 10 episodes of Thriller (1960–62, several based on his own stories), and 10 episodes of Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1960–62). In 1962, he wrote the screenplay for The Cabinet of Caligari (1962), an unhappy experience (see Films section below).

In 1962, Bloch penned the story and teleplay "The Sorcerer's Apprentice" for Alfred Hitchcock Presents. The episode was shelved when the NBC Television Network and sponsor Revlon called its ending "too gruesome" (by 1960s standards) for airing. Bloch was pleased later when the episode was included in the program's syndication package to affiliate stations where not one complaint was registered. Today, due to public domain status, the episode is readily available in home media formats from numerous distributors and is even available on free video on demand.[20][21][22][23] For details of Bloch's scripts for Hitchcock shows see[24]

His TV work did not slow Bloch's fictional output. In the early 1960s he published several novels, including The Dead Beat (1960), and Firebug (1961) (for which Harlan Ellison, then an editor at Regency Books, contributed the first 1200 words).[25] In 1962 his novels The Couch (1962) (the basis for the screenplay of his first movie, filmed the same year) and Terror (originally titled Kill for Kali) were published.[26] Stephen King has written that "What Bloch did with such novels as The Deadbeat, The Scarf, Firebug, Psycho, and The Couch was to re-discover the suspense novel and reinvent the antihero as first discovered by James Cain." [27]

Bloch wrote original screenplays for two movies produced and directed by William Castle, Strait-Jacket (1964) and The Night Walker (1964), along with The Skull (1965). The latter film was based on his short story "The Skull of the Marquis de Sade".

Marriages and family

On October 2, 1940, Bloch married Marion Ruth Holcombe; it was reportedly a marriage of convenience designed to keep Bloch out of the army.[28] During their marriage, she suffered (initially undiagnosed) tuberculosis of the bone, which affected her ability to walk.[29]

After working for 11 years for the Gustav Marx Advertising Agency in Milwaukee, Bloch left in 1953 and moved to Weyauwega, Marion's home town, so she could be close to friends and family. Although she was eventually cured of tuberculosis, she and Bloch divorced in 1963. Bloch's daughter Sally (born 1943) elected to stay with him.

On January 18, 1964, Bloch met recently widowed Eleanor ("Elly") Alexander (née Zalisko) — who had lost her first husband, writer/producer John Alexander, to a heart attack three months earlier — and made her his second wife in a civil ceremony on the following October 16. Elly was a fashion model and cosmetician.[30] They honeymooned in Tahiti, and in 1965 visited London, then British Columbia.[31] They remained happily married until Bloch's death. Elly remained in the Los Angeles area for several years after selling their Laurel Canyon Home to fans of Bloch, eventually choosing to go home to Canada to be closer to her own family. She died March 7, 2007, at the Betel Home in Selkirk, Manitoba, Canada. Her ashes have been placed next to Bloch's in a similar book-shaped urn at Pierce Brothers in Westwood, California.[32]

The 1960s: Screenwriting continued

In 1964 Bloch wrote two movies for William Castle – Strait-Jacket and The Night Walker.

Bloch's further TV writing in this period included The Alfred Hitchcock Hour (7 episodes, 1962–1965),[33] I Spy (1 episode, 1966), Run for Your Life (1 episode, 1966), and The Girl from U.N.C.L.E. (1 episode, 1967). He notably penned three original scripts for the original series of Star Trek (1966–67): "What Are Little Girls Made Of?", "Wolf in the Fold" (a Jack the Ripper variant), and "Catspaw".

His novels of the second half of the 1960s include Ladies Day/This Crowded Earth (1968)(sf), The Star Stalker (1968) and The Todd Dossier (1969) (the book publication of which bears the byline "Collier Young").

In 1968 Bloch returned to London to do two episodes for the Hammer Films series Journey to the Unknown for Twentieth Century Fox. One of the episodes, "The Indian Spirit Guide", was included in the TV movie Journey to Midnight (1968).

Following the 1965 movie The Skull, which was based on a Bloch story but scripted by Milton Subotsky, between 1966 and 1972 Bloch wrote no less than five feature movies for Amicus Productions – The Psychopath, The Deadly Bees, Torture Garden, The House That Dripped Blood and Asylum. The last two films featured stories written by Bloch that were printed first in anthologies he wrote in the 1940s and early 1950s.

In 1969 he was invited to the Second International Film Festival in Rio de Janeiro, March 23–31, along with other science fiction writers from the US, Britain and Europe.[34]

The 1970s and '80s

During the 1970s Bloch wrote two TV movies for director Curtis Harrington – The Cat Creature and The Dead Don't Die. The Cat Creature was an unhappy production experience for Bloch. Producer Doug Cramer wanted to do an update of Cat People (1942), the Val Lewton classic. Bloch says: "Instead I suggested a blending of the elements of several well-remembered films, and came up with a story line which dealt with the Egyptian cat-goddess (Bast), reincarnation and the first bypass operation ever performed on an artichoke heart."[35] A detailed account of the troubled production of the film is described in Bloch's autobiography.[36]

Bloch meanwhile (interspersed between his screenplays for Amicus Productions), penned single episodes for Night Gallery (1971), Ghost Story (1972), The Manhunter (1974), and Gemini Man (1976).

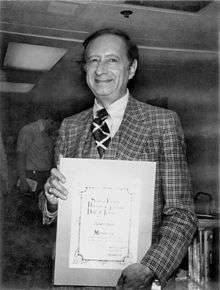

In 1975 Bloch was presented with a Lifetime Achievement Award at the First World Fantasy Convention held in Providence, Rhode Island. The award was a bust of H.P. Lovecraft. An audio recording was made of Robert Bloch during that 1975 convention, accessible at the following link.

Bloch continued to published short story collections throughout this period. His Selected Stories (reprinted in paperback with the incorrect title The Complete Stories) appeared in three volumes just prior to his death, although many previously uncollected tales have appeared in volumes published since 1997 (see below). Bloch also contributed the story "Heir Apparent," set in Andre Norton's Witch World, to Tales of the Witch World (Vol. 1), NY: Tor, 1987.

His numerous novels of this two decade period range from science fiction - Sneak Preview (1971) - through horror novels such as the Lovecraftian Strange Eons (1978) and Night of the Ripper (1984); the non-supernatural mystery There is a Serpent in Eden (1979); his two sequels to the original Psycho (Psycho II and Psycho House), and late novels such as the thriller Lori (1989) and The Jekyll Legacy with Andre Norton (1991), a sequel to Robert Louis Stevenson's Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde. Omnibus editions of hard-to-acquire early novels appeared as Unholy Trinity (1986) and Screams (1989).

Bloch's screenplay-writing career continued active through the 1980s, with teleplays for Tales of the Unexpected (one episode, 1980), Darkroom (two episodes,1981), Alfred Hitchcock Presents (1 episode, 1986), Tales from the Darkside (three episodes, 1984–87) and Monsters (three episodes, 1988–1989 - "Beetles", "A Case of the Stubborns" and "Everybody needs a Little Love"). No further screen work appeared in the last five years before his death, although an adaptation of his "collaboration" with Edgar Allan Poe, "The Lighthouse", was filmed as an episode of The Hunger in 1998.

In February 1991 he was given the Honor of Master of Ceremonies at the first World Horror Convention held in Nashville, Tennessee.

Death and Legacy

In 1994, Bloch died of cancer at the age of 77.[37][38][39] in Los Angeles after a writing career lasting 60 years, including more than 30 years in television and film. He was cremated and interred in the Room of Prayer columbarium at Westwood Village Memorial Park Cemetery in Los Angeles.[40] His wife Elly is also interred there.

The Robert Bloch Award is presented at the annual Necronomicon convention. Its recipient in 2013 was editor and scholar S.T. Joshi. The award is in the shape of the Shining Trapezohedron as described in H.P. Lovecraft's tale dedicated to Bloch, The Haunter of the Dark.

Writings on Bloch

An early reference work by Australian writer Graeme Flanagan, Robert Bloch: A Bio-Bibliography (1979) includes interviews with Bloch and memoirs by fellow writers such as Harlan Ellison, Richard Matheson, Mary Elizabeth Counselman and Fritz Leiber.

Stephen King dedicated his 1981 book Danse Macabre to Bloch, along with Jorge Luis Borges, Ray Bradbury, Frank Belknap Long, Donald Wandrei and Manly Wade Wellman.

An essay by Lee Prosser about Robert Bloch was published in The Roswell Literary Review at Roswell, New Mexico, 1996.

The Existential Robert Bloch, an interview by Lee Prosser with Bloch in March 1983, was published at Michael G. Pfefferkorn's The Bat is My Brother website.[41]

"A Conversation With Lee Prosser," an in-depth interview with Lee Prosser about Bloch by Michael G. Pfefferkorn on May 31, 2002 was published at Michael G. Pfefferkorn's The Unofficial Robert Bloch Website.

Randall D. Larson is the premier Bloch scholar. He published and edited an early tribute to Bloch, The Robert Bloch Fanzine (Fandom Unlimited, 1972). He later authored three reference books about Robert Bloch: The Robert Bloch Reader's Guide (1986, a literary analysis of Bloch's entire output through 1986), The Complete Robert Bloch (1986, an illustrated bibliography of Bloch's writing), and The Robert Bloch Companion (1986, collected interviews). In addition, an issue of Paperback Parade magazine (No. 39, August 1994) contains an article by Larson on collecting Bloch – "Paperblochs: Robert Bloch in Paperback."

Crypt of Cthulhu magazine No 40 (Vol. 5 No. 6 St. John's Eve, 1986). was a special Robert Bloch issue. It included some story reprints by Bloch, essays on his work and bibliography of his books by R. Dixon Smith.

In the anthology My Favorite Horror Story (DAW, 2000), edited by Mike Baker and Martin H. Greenberg, influential horror writers in the field picked their favourite stories. Out of 15 tales, only Bloch and H.P. Lovecraft are represented by two stories. Of Bloch's, Stephen King chose "Sweets to the Sweet" and Joe R. Lansdale chose "The Animal Fair". The selected Lovecraft stories are "The Colour Out of Space" and "The Rats in the Walls."

There is an essay on Bloch's work, with particular reference to the novels Psycho and The Scarf, in S. T. Joshi's book The Modern Weird Tale (2001). Joshi examines Bloch's literary relationship with Lovecraft in a further essay in The Evolution of the Weird Tale (2004).

A more recent essay collection focusing on a range of Bloch's work is Robert Bloch: the Man Who Collected Psychos, edited by Benjamin J. Szumskyj (McFarland, 2009).

Comic adaptations

A number of Bloch's works have been adapted in graphic form for comics. These include:

- "The Beasts of Barsac" (aka "The Living Dead") in Vampire Tales

- "The Past Master" in Christopher Lee's Treasury of Terror. NY: Pyramid, 1967.

- "The Shambler from the Stars"

- a. in Journey Into Mystery 3 (Marvel Comics, Feb 1973). Script by Ron Goulart, art by Jim Starlin and Tom Palmer.

- b. in Masters of Terror 1 (Marvel large size b&w, July 1975).

- "The Man Who Cried Wolf" (as "The Man Who Cried Werewolf!") in Monsters Unleashed 1 (Marvel Comics, large size b&w, 1973), PP27–35. Script by Gerry Conway, art by Pablo Marcos.

- "The Shadow from the Steeple" in Journey into Mystery 5 (Marvel Comics, June 1973)

- "The Fear Planet" (as "And the Blood Ran Green") in Starstream 4 (Whitman, 1976). Script by Arnold Drake, art by Nevio Zaccara.

- Hell on Earth. Standalone graphic adaptation by Keith Giffen and Robert Loren Fleming, based on Bloch's story from Weird Tales (1942). DC Comics, 1985.

- "A Toy for Juliette" in Deepest Dimensions 1 (1993).

- Lori Standalone graphic adaptation by Ben Templesmith. (IDW, 2009).

- "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper"

- a. in Journey into Mystery 2 (Marvel Comics, Dec 1972). Script by Ron Goulart, art by Gil Kane and Ralph Reese.

- b. in Masters of Terror 1 (Marvel large size b&w, July 1975)

- c. as three-issue mini-series (IDW, 2010) and also collected as trade paperback (IDW, 2011). Scripted by Joe R. Lansdale.

- "Final Performance" in Doomed 1 (IDW, 2010). Adapted by Kristian Donaldson and Chris Ryall. Also included in Completely Doomed graphic anthology (IDW, 2011).

- "Warm Farewell" in Doomed 2 (IDW, 2010)

- "Fat Chance" in Doomed 3 (IDW, 2010).(Also includes a remembrance of Bloch by Jack Ketchum.)

- "Ego Trip" in Doomed 4 (IDW, 2010).

- "That Hellbound Train". 3-issue mini-series. (IDW, 2011). Scripted by Joe R. Lansdale

The comic Aardwolf (No 2, Feb 1995) is a special tribute issue to Bloch. It contains brief tributes to Bloch from Harlan Ellison, Ray Bradbury, Richard Matheson, Julius Schwartz and Peter Straub incorporated within a piece called "Robert Bloch: A Retrospective" compiled by Clifford Lawrence. The first part of the text of Bloch's story 'The Past Master" is also reprinted in this issue.

Bloch also contributed a script as part of the one-shot comic Heroes Against Hunger".

Audio adaptations

A number of Bloch's works have been adapted for audio productions. For details on Stay Tuned for Terror, see 1940s section above.

Other adaptations include:

- "Almost Human". May 1950 NBC radio broadcast from Dimension X and 1955 NBC radio broadcast from show X Minus One. Available for download from: . Audio of this story also included on Isaac Asimov and Martin H. Greenberg (eds) Friends, Robots, Countrymen. Dercum Audio, 1997. ISBN 1-55656-256-X.

- Gravely, Robert Bloch. Alternate World Recordings, 1976. LP. Bloch himself reads "That Hellbound Train" and "Enoch".

- Blood! The Life and Times of Jack the Ripper. Alternate World recordings, 1977. LP (2 record set). Bloch himself reads "Yours Truly Jack the Ripper" and "A Toy for Juliette". Harlan Ellison reads his "The Prowler in the City at the Edge of the World"

- Psycho House (Psycho III). Sunset Productions/Audio gems, June 1992. ISBN 1-56431-037-X. Read by Mike Steele. 2 cassettes. Abridged?

- Thrillogy. Read by Roger Zelazny. Sunset Productions, 1993. Includes the three Bloch stories "That Hellbound Train", "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper", and "The Movie People. (1 cassette, running time 90 mins). ISBN 1-56431-045-0

- Psycho. Read by Kevin McCarthy. Listen for Pleasure, 1986. ISBN 0-88646-165-0 (2 cassettes, abridged, running time 2 hours). Reissued Feb 1999 ISBN 0-88646-492-7.

- Psycho II: The Nightmare Continues. Sunset Productions, Aug 1992. ISBN 1-56431-019-1.

- "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper" on The Greatest Mysteries of All Time. Newstar Media, 1994. ISBN 0-7871-2092-8. 1 cassette. Packaged with "Hight Darktown" by James Ellroy. Read by Arte Johnson and Robert Forster. Running time ?

- The Living Dead. Stellar Audio Vol 5: Horror edition (Brilliance Audio), Aug 1996. Packaged with You'll Catch Your Death by P.N. Elrod. ISBN 1-56740-970-9. 1 cassette. Running time 90 mins.

- Psycho. Read by William Hootkins. Magmasters Sound Studios/ABC Audio, 1997. (2 cassettes, running time 3 hours). ISBN 1-84007-002-1.

- "The Movie People" on Hollywood Fantasies – Ten Surreal Visions of Tinsel Town. Dove Audio/Audio Literature, 1997. 4 cassettes. Running time 6 hours. Unabridged. ISBN 0-7871-0946-0

- "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper". On The Greatest Horror Stories of the 20th Century edited by Martin Greenberg. Dove Audio, 1998. Read by various readers. 4 cassettes. Running time 6 hours. ISBN 0-7871-1723-4

- Psycho. BBC Radio Collection, June 2000. Read by William Hope. ? cassettes. Abridged. ISBN 0-563-47710-5.

- "A Good Knight's Work". Adapted by George Zarr, performed by a full cast. Seeing Ear Theatre, 2001. Running time 44 mins.

- Psycho. Blackstone Audio, Feb 2009. Read by Paul Michael Garcia. ISBN 978-1-4332-5705-6 (4 cassette set), 9781433257094 (1 mp3-cd), 9781433257063 (5 cd set). Unabridged. Running times 5.6 hours. Playaway preloaded digital audio ed with earbuds, Sept 2009 ISBN 1-4332-5713-0

- This Crowded Earth. Librivox, March 2009. Read by Gregg Margarite. (3-CD set, running time 3 hours, 30 mins). Available for download from Librivox:

- Psycho. (In German). Read by Matthias Brandt. (5-CD set). Der Audio Verlag, 2011. ISBN 978-3-89813-975-5

Various recordings of Bloch speaking at fantasy and sf conventions are also extant. Many of these are available for download from Will Hart's CthulhuWho site:

Bibliography

Novels

- In the Land of Sky-Blue Ointments (with Harold Gauer) (c. 1938) (unpublished, though characters and episodes from this book appear in later Bloch short stories, such as "The Travelling Salesman" and "The Strange Island of Dr Nork". The character Lefty Feep also appears for the first time in this work. .[42][43] Bloch owned the complete manuscript of the novel, which he described as "never intended or submitted for publication.".[44] Bloch's estate has blocked posthumous publication[45]). Plot summary at:

- Nobody Else Laughed (with Harold Gauer) (1939) (unpublished)[46]

- The Scarf (1947, rev. 1966)

- Spiderweb (1954)

- The Kidnapper (1954)

- The Will to Kill (1954)

- Shooting Star (1958) (note: published in a double volume with the ss collection Terror in the Night) No ISBN – identified only as Ace Double D-265

- This Crowded Earth (1958) (original magazine appearance; published as book in double format with Ladies Day 1968 – see below)

- Psycho (1959). UK: Robert Hale, April 1960. (adapted into the 1960 film, Psycho, directed by Alfred Hitchcock; later remade in 1998 by Gus Van Sant)

- The Dead Beat (1960). No ISBN. An 'Inner Sanctum' Mystery. Library of Congress Card No 60-6100.

- Firebug (1961) Regency Books RB 101.

- The Couch (1962). Novelisation by Bloch of his screenplay for the previously filmed movie (see Movies section below).

- Terror (Belmont Books, 1962) [ISBN unspecified]; Belmont L92-537 (Working title: Amok).

- Ladies Day / This Crowded Earth (1968) A Belmont Double. Belmont B60-080 OCLC 1649428

- The Star Stalker (Pyramid Books, 1968). Pyramid T-1869.

- The Todd Dossier (1969, Delacorte US; Macmillan UK – no ISBN.)(as by Collier Young). Note: The byline on this book is not a Bloch pseudonym; Collier Young was a film producer who had secured a book deal with Bloch for his planned film called THE TODD DOSSIER. Bloch wrote the novel based on a story by Joan Didion and John Gregory Dunne. The film was never made; Bloch, who had contracted for a paperback release, was shocked to learn that the producer had placed his own name on the book as author when it was published in hardcover editions.[47]

- Sneak Preview (Paperback Library, 1971) OCLC 2487497

- It's All in Your Mind (Curtis Books, 1971). Reprinted from its Imaginative Tales 1955 magazine appearance, where it was titled 'The Big Binge". "The Big Binge" can also be found in The Lost Bloch, Volume One (see below).

- Night World (Simon & Schuster, 1972). UK: Robert Hale, 1974. ISBN 0-7091-3805-9

- American Gothic (Simon & Schuster, 1974)ISBN 0-671-21691-0. Note: This novel was inspired by the true life story of serial killer H.H. Holmes. Bloch also wrote a 40,000-word essay based on his research for the novel, "Dr Holmes' Murder Castle" (first published in Reader's Digest Tales of the Uncanny, 1977; since reprinted in Crimes and Punishments: The Lost Bloch, Vol 3", 2002).

- Strange Eons (Whispers Press, 1978) (a Cthulhu Mythos novel). ISBN 0-918372-30-5 (trade ed); 0-918372-29-1 (signed/boxed ed.) Third runner-up in the Best Novel category, Balrog Award, 1980.

- There Is a Serpent in Eden (1979). Reissued as The Cunning (Zebra Books, 1979). ISBN 0-89083-825-9

- Psycho II (Whispers Press, 1982). 0-91832-09-7 (trade ed); 0-918372-08-9 (signed/boxed ed, 750 copies). (Unrelated to the film of the same name)

- Twilight Zone: The Movie. (Warner Books, 1983). Novelisation of the Warner Bros movie, based on stories by John Landis, George Clayton Johnson, Richard Matheson, Josh Rogan, and Jerome Bixby. ISBN 0-446-30840-4

- Night of the Ripper (Doubleday,1984).ISBN 0-385-19422-6. Novel about Jack the Ripper.

- Unholy Trinity (collects The Scarf, The Couch and The Dead Beat(Scream/Press Press, 1986). ISBN 0-910489-09-2 (Trade edition and 350 copy boxed ed signed by author and artist bear the same ISBN)

- Lori (Tor, 1989) ISBN 0-312-93176-X.

- Screams: Three Novels of Suspense (collects The Will to Kill, Firebug and The Star Stalker)(Underwood-Miller, 1989) ISBN 0-88733-079-7 (trade edition); 0-88733-080-0 (signed edition, 300 numbered copies).

- Psycho House (Tor, 1990) ISBN 0-312-93217-0.(Unrelated to the films Psycho II, Psycho III or Psycho IV: The Beginning)

- The Jekyll Legacy (Tor, 1991) ISBN 0-312-85037-9.

- Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper (1991) (Pulphouse; a 100-copy hardbound signed edition of Bloch's famous short story) ISBN 1-56146-906-8

- The Thing (1993) (Pretentious Press; a limited edition of 85 copies, only 9 bound in cloth, of the author's first appearance in print – a parody of H.P. Lovecraft which originally appeared in the April 1932 issue of The Quill, his Lincoln High School literary magazine)

- Psycho – The 35th Anniversary Edition (Gauntlet Press, 1994). ISBN 0-9629659-9-5. Limited edition of 500 copies. The last work to be signed by Bloch before his death; includes a new intro by Richard Matheson and a new Afterword by Ray Bradbury)

Short-story collections

- The Thing (1932) actually a single short story (parodying the style of H.P. Lovecraft), the author's first, but initially published in book form by The Pretentious Press in (1993)

- A Portfolio of Some Rare And Exquisite Poetry by the Bard of Bards (1937 or 1938) written under the pseudonym Sarcophagus W. Dribble. One page folded to make 4. Poetry. This item has been stated to be Bloch's first true book; however it actually seems to have appeared in the fanzine Novacious No 2 (March 1939) edited by Forrest J. Ackerman and Myrtle R. Douglas ('Morojo'); distributed by the Fantasy Amateur Press Association. A copy of this fanzine is held by the Special Collections at Kuhn Library, University of Maryland Baltimore.

- The Opener of the Way (Arkham House, 1945)

- Sea Kissed (London: Utopian, 1945)

- Terror in the Night (Ace Books, 1958) (note: published in a double volume with the novel Shooting Star) No ISBN – D-265 on spine.

- Pleasant Dreams: Nightmares (Arkham House,1960)

- Blood Runs Cold (1961). UK: Robert Hale, 1963. No ISBN.

- Nightmares (1961)

- More Nightmares (Belmont Books, 1961). No ISBN – Belmont #L92-530

- Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper (Belmont Books, 1962) No ISBN – L 92-527 on spine.

- Atoms and Evil (1962)

- Horror 7 (Belmont Books, 1963). No ISBN. Belmont #90–275. Australian edition: Horwitz, 1963.

- Bogey Men (Pyramid Books, March 1963) [ISBN unspecified]; Pyramid F-839. Includes the essay "Psycho-Logical Bloch" by Sam Moskowitz.

- House of the Hatchet (Belmont Books, 1960). UK: Tandem Books, 1965. No ISBN – T19 on spine.

- The Skull of the Marquis de Sade (1965). UK: Robert Hale, 1975.

- Tales in a Jugular Vein (Pyramid Books, 1965) No ISBN – R-1130 on spine.

- Chamber of Horrors (Award Books, 1966) [ISBN unspecified]; Award Books A187X.

- The Living Demons (Belmont Books, Sept 1967) No ISBN – Belmont B50-787.

- Dragons and Nightmares: Four Short Novels (Mirage, 1968) No ISBN . Voyager series V-102.

- Bloch and Bradbury: Whispers from Beyond (Peacock Press, 1969) No ISBN.

- Fear Today, Gone Tomorrow (Award Books/Tandem Books, 1971) No ISBN Award/Tandem 426 & A811S on spine; AQ 1469 on front cover.

- The King of Terrors: Tales of Madness and Death (The Mysterious Press, 1977) ISBN 0-89296-029-9 (trade ed); 0-89296-030-2 (limited ed).

- The Best of Robert Bloch (Del Rey/Ballantine, 1977). ISBN 0-345-25757-X. Introduction by Lester Del Rey.

- Cold Chills (Doubleday, 1977). ISBN 0-385-12421-X.

- Out of the Mouths of Graves (Mysterious Press, 1978) ISBN 0-89296-043-4 (trade ed); 0-89296-044-2 (limited ed).

- The Laughter of a Ghoul/What Every Young Ghoul Should Know (Necronomicon Press, 1978)

- Such Stuff as Screams Are Made Of (Ballantine Books, 1979) ISBN 0-345-27996-4.

- Mysteries of the Worm (Zebra Books, 1981). ISBN 0-89083-815-1. Introduction "Demon-Dreaded Lore" by Lin Carter. Afterword by Robert Bloch.

- Midnight Pleasures (Doubleday, 1987) ISBN 0-385-19439-0.

- Lost in Space and Time With Lefty Feep (Creatures at Large Press, 1987). ISBN 0-940064-03-0 (trade ed); 0-940064-01-4 (boxed/deluxe ed, 250 copies signed). Note: This book was designated "Volume One" but in fact no further volumes of the series were published, leaving a number of the Lefty Feep stories uncollected.

- Selected Stories of Robert Bloch (Underwood-Miller, 1987, 3 vols).

Note: The following three entries represent paperback reprints of the Underwood Miller Selected Stories set. Complete Stories is a misnomer as these three volumes do not contain anywhere near the complete oeuvre of Bloch's short fiction.

- The Complete Stories of Robert Bloch: Volume 1: Final Reckonings (1987)

- The Complete Stories of Robert Bloch: Volume 2: Bitter Ends (1987)

- The Complete Stories of Robert Bloch: Volume 3: Last Rites (1987)

- Fear and Trembling (1989)

- Mysteries of the Worm (rev. 1993) from Chaosium books. Adds three additional stories not included in the first edition.

- The Early Fears (1994). Fedogan & Bremer. ISBN 1-878252-12-7 (trade ed); 1-878252-13-5 (limited ed).

- Flowers from the Moon and Other Lunacies (Arkham House, 1998) ISBN 0-87054-172-2. Introduction by Robert M. Price. Collects rarities from the Bloch canon, previously published in Weid Tales, Strange Stories and Rogue magazines; of its 20 stories, 15 are not readily obtainable outside the original pulps where they appeared.

- The Lost Bloch: Volume 1: The Devil With You! (Subterranean Press, 1999) ISBN 1-892284-19-7. (Limited ed of 724 numbered copies signed by editor/introducer David J. Schow and Foreword writer Stefan Dziemaniowicz). Includes interview with Bloch, 'An Hour with Robert Bloch" conducted by David J. Schow. One of the stories included is "The Big Binge" (originally in Imaginative Tales in 1955 and reprinted as the short novel It's All in Your Mind in 1971, see above). The Lost Bloch supplements Flowers from the Moon in reprinting rare and unreprinted Bloch stories; however at early 2011 around 50 Bloch stories remain uncollected[48]

- The Lost Bloch: Volume 2: Hell on Earth (2000). ISBN 1-892284-63-4. (Limited ed of 1250 numbered copies signed by editor/introducer David J. Schow and Foreword writer Douglas E. Winter). Includes afterword by Schow and interview "Slightly More than Another Hour with Robert Bloch" by J. Michael Straczynski.

- The Lost Bloch: Volume 3: Crimes and Punishments (Subterranean Press, 2002) ISBN 1-931081-16-6. (Limited ed 750 numbered copies signed by editor/introducer David J. Schow). Includes introductory piece by Gahan Wilson, interview "Three Hours and Then Some with Robert Bloch" by Douglas E. Winter and "My Husband, Robert Bloch" by Eleanor Bloch.

- The Reader's Bloch: Volume 1: The Fear Planet and Other Unusual Destinations (Subterranean Press, 2005; limited ed, signed by editor, 750 numbered and 26 lettered copies). Edited by Stefan R. Dziemanowicz, who provides an introduction, "Future Imperfect". Collects more Bloch rarities; most of its 20 stories are science fiction, and are otherwise unobtainable outside their original magazine appearances.

- The Reader's Bloch: Volume 2: Skeleton in the Closet and Other Stories (Subterranean Press, 2008; 750 numbered copies signed by the editor). Edited by Stefan R. Dziemanowicz. No intro. An unthemed collection of Bloch rarities, most of whose 16 stories are otherwise unobtainable outside their original magazine appearances.

- Mysteries of the Worm (Chaosium, rev. 2009) ISBN 1-56882-176-X. Preface "De Vermis Mysteriis" by Robert M. Price. Includes original Introduction by Lin Carter and After Word by Robert Bloch. Adds four additional stories not included in the first two editions.

Anthologies and collections edited by Bloch

- The Best of Fredric Brown (Nelson Doubleday, 1976). No ISBN. Book Club ed. 3180 on rear jacket flap.

- Psycho-Paths. (Tor, 1991). ISBN 0-312-85048-4.

- Monsters in Our Midst (Tor, 1993). ISBN 0-312-85049-2.

- Robert Bloch's Psychos (1997). ISBN 1-56865-637-8. This anthology was being edited by Robert Bloch until his death in 1994. Martin H. Greenberg completed the editorial work posthumously.

Non-fiction

- The Eighth Stage of Fandom (1962). Advent – no ISBN. Wildside Press reprint, 1992, with new intro by Wilson Tucker and new afterword by Harlan Ellison, ISBN 1-880448-16-5

- Out of My Head (1986) (essays). NESFA Press. ISBN 0-915368-30-7 (trade ed); 0-915368-87-0 (slipcased ed). Edition limited to 800 numbered copies, the first 200 being slipcased.

- Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorized Autobiography (Tor, 1993).

- Robert Bloch: Appreciations of the Master (Tor, 1995). This volume is a tribute to Bloch collecting essays by many writers who knew or worked with him, together with reprints of several Bloch stories.

Awards

- 1959. "That Hell-Bound Train" Hugo Award for Best Short Story[49][50]

- 1959: E. Everett Evans Memorial Award for Fantasy and Science Fiction Work

- 1960: Ann Radcliffe Award for Literature (Count Dracula Society) The Count Dracula Society was founded by Dr Donald A. Reed, who also founded the Academy of Science Fiction, Fantasy and Horror Films.

- 1960: Edgar Allan Poe Award (Special Scroll) (for Psycho) Mystery Writers of America[51]

- 1960: Screenwriter's Annual Award nominated by Screenwriter's Guild (for Psycho)

- 1964: Inkpot Award for Science Fiction[52]

- 1965: Third Trieste Film Festival Award (for The Skull)

- 1966: Ann Radcliffe Award for Television (Count Dracula Society)

- 1973: First prize, La 2de Convention Du Cinema Fantastique De Paris (for Asylum)

- 1974: Award for Service to the Field of Science Fantasy Los Angeles Science Fiction Society

- 1975. World Fantasy Award, Life Achievement[53]

- 1978: Fritz Lieber Fantasy Award

- 1979: Reims Festival Award[52]

- 1984. Hugo Special Award for 50 years as a science fiction professional[54]

See also 42nd World Science Fiction Convention

- 1984: Lifetime Career Award, Atlanta Fantasy Fair[52]

- 1985: Twilight Zone Dimension Award[52]

- 1989. Bram Stoker Award, Life Achievement[55]

- 1993. Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorized Autobiography Bram Stoker, Superior Achievement in Non-Fiction [56]

- Special award at the first NecronomiCon. (After his death, this award was renamed in his honor).[57]

- 1994. The Early Fears Bram Stoker, Superior Achievement in a Fiction Collection[58]

- 1994. "The Scent of Vinegar" Bram Stoker, Superior Achievement in Long Fiction[58]

Movies

The following is a list of films based on Bloch's work. For some of these he wrote the original screenplay; for others, he supplied the story or a novel (as in the case of Psycho) on which the screenplay was based.

- Psycho (1960) Dir: Alfred Hitchcock

- The Couch (1962). Screenplay by Bloch, based on a story by Blake Edwards and director Owen Crump. Bloch later novelized his own screenplay. Stars Grant Williams.

- The Cabinet of Caligari (1962). Dir: Roger Kay. The story of how director Roger Kay tried to rob Bloch of the writing credit for the film and of how Bloch won out is told in Bloch's autobiography.[59]

- Strait-Jacket (1964). Original screenplay by Bloch. The first of his two screenplays for director William Castle.

- The Night Walker (1964). Original screenplay by Bloch. The second of two screenplays for director William Castle. The screenplay was later novelized by Sidney Stuart (a pseudonym of Michael Avallone), with an introduction by Bloch. (The Night Walker, Award Books, Dec 1964. [ISBN unspecified]; Award KA124F)

- The Skull (1965). The first of Bloch's six movies made for Amicus Productions. Based on Bloch's story but scripted by Milton Subotsky. Dir: Freddie Francis.

- The Psychopath (1966). 2nd of Bloch's Amicus movies. Original screenplay by Bloch. Dir: Freddie Francis.

- Torture Garden (1967). 3rd of Bloch's Amicus movies. Screenplay by Bloch based on four of his stories, including The Man Who Collected Poe (about Edgar Allan Poe). Dir: Freddie Francis

- The Deadly Bees (1967). 4th of Bloch's Amicus movies. Screenplay by Bloch based on Gerald Heard's A Taste of Honey Dir: Freddie Francis.

- The House That Dripped Blood (1970). 5th of Bloch's Amicus movies. Screenplay by Bloch based on four of his stories (except that Russ Jones adapted Waxworks, uncredited). Dir: Peter Duffell.

- Asylum (1972, aka House of Crazies). 6th and final of Bloch's Amicus movies. Screenplay by Bloch based on four of his stories. The screenplay was novelized by William Johnston, (Asylum, Bantam Books, Dec 1972. [ISBN unspecified]; Bantam 9195). Dir: Roy Ward Baker. Note: Bloch's story "Lucy Comes to Stay", one of the four stories incorporated in the film can be found reprinted in Peter Haining (ed) Ghost Movies: Classics of the Supernatural, Severn House, 1995 as "Asylum".

- The Cat Creature (TV movie, 1973). Original screenplay by Bloch, based upon a story by himself, Douglas S. Cramer and Wilfred Lloyd Baumes. Directed by Curtis Harrington. Starring Gale Sondergaard. For further details see under '1970's and 1980s' in Biography above.

- The Dead Don't Die (NBC TV movie 1975). Screenplay by Bloch based on his story (Fantastic Adventures, July 1951). Directed by Curtis Harrington. Starring Ray Milland, George Hamilton, Joan Blondell.

- The Return of Captain Nemo (1978). A TV mini-series also released theatrically as The Amazing Captain Nemo. (Bloch penned one episode,"Atlantis Dead Ahead", in collaboration with Larry Alexander). Dir: Alex March.

- Psycho (1998). Dir: Gus Van Sant. Based on the Hitchcock film from Robert Bloch's original novel.

- Earthman's Burden. Some scenes from Bloch's incomplete screenplay for this unproduced movie, to have been based on the Hoka stories of Gordon R. Dickson and Poul Anderson appear in Richard Matheson and Ricia Mainhardt, eds, Robert Bloch: Appreciations of the Master. NY: Tor, 1995, pp. 157–63.

Unproduced screenplays

Bloch wrote a number of screenplays which remain unproduced. These include Merry-Go-Round for MGM (based on Ray Bradbury's story "Black Ferris");[60] Night-World (from Bloch's novel, for MGM); and Day of the Comet (from the H.G. Wells story), and a television adaptation of "Out of the Aeons". See also The Todd Dossier under the Bibliography section above.

Documentaries

Bloch appeared in the documentary The Fantasy Film Worlds of George Pal (1985) (Produced and directed by Arnold Leibovit).

References

- ↑ Haynes, Diana (c. 1998). a.k.a.: 50 Years of American Literary Pseudonyms. Carlsbad, California: Primulum Books Ltd. p. 4. ISBN 0-9666470-0-9.

- ↑ The essay was previously collected in The Lost Bloch, Volume Three: Crimes and Punishments (2002) "Bibliography: The Shambles of Ed Gein". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Library of America. "True Crime: An American Anthology". Library of America. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Larson, Randall (1989). The Bloch Companion: Collected Interviews 1969–1986. Starmont House. ISBN 1-55742-147-1.

- 1 2 Milwaukee Journal, April 6, 1935.

- ↑ Robert Bloch, "The Seacrher After Horror". World Fantasy 1983: Sixty Years of Weird Tales (conevention program book), p. 15

- ↑ Haining, Peter (1975). The Fantastic Pulps. Victor Gollancz Ltd. ISBN 0-575-02000-8.

- ↑ Von Ruff, Al. "Bibliography: The Feast in the Abbey". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Von Ruff, Al. "Bibliography: The Secret in the Tomb". Internet Speculative Fiction Database. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ Library of America (September 23, 2010). "What Robert Bloch owes to H. P. Lovecraft". Reader's Almanac: The Official Blog of the Library of America. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

- ↑ "Meet the Authors", Amazing Stories, August 1938, p.146

- ↑ "Lefty Feep and I" in Bloch's Out of My head. Cambridge MA: NESFA Press, 1986, 125–30.

- ↑ For further information see "Stay Tuned for Terror" in Bloch's Out of My Head. Cambridge MA; NESFA Press, 1986, 33–41

- ↑ Zinna, Eduardo. "Yours Truly, Jack the Ripper". Casebook: Jack the Ripper.

- ↑ Meikle, p. 110

- ↑ Woods and Baddeley, p. 68

- ↑ http://www.bmonster.com/horror29.html

- ↑ Robert Bloch. "Building the Bates Motel". Mystery Scene, No 40 (1993):19, 26, 27, 58.

- ↑ http://www.darkecho.com/darkecho/horroronline/bloch.html

- ↑ allmovie.com

- ↑ Grams, Martin and Patrik Winstrom, The Alfred Hitchcock Presents Companion c. 2001, OTR Publishing, Churchville, Maryland, ISBN 0-9703310-1-0 (pp. 385–388)

- ↑ Snopes.com

- ↑ Internet Archive

- ↑ "Robert Bloch – Alfred Hitchcock Wiki". Hitchcockwiki.com. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ Bloch 1993, p. 255

- ↑ Bloch 1993, p. 270

- ↑ Stephen King, "A Profile of Robert Bloch". World Fantasy 1983: Sixty Years of Weird Tales (convention program book), pp. 11-12

- ↑ Bloch 1993, p. 158

- ↑ Bloch 1993, pp. 215–217

- ↑ Bloch 1993, pp. 308–309

- ↑ Bloch 1993, pp. 304–313

- ↑ Eleanor "Elly" Alexander Bloch widow of Robert Bloch at Find A Grave

- ↑ Perry, Dennis R.; Carl H. Sederholm (2013). "Adapting Poe, Adapting Hitchcock: Robert Bloch in the Shadow of Hitchcock's Television Empire". Clues: A Journal of Detection. 31 (1): 91–101. doi:10.3172/CLU.31.1.91. Retrieved April 13, 2013.

- ↑ Philip José Farmer wrote an essay, "Report", for Luna 6, 1969, which also appeared as "The Josés from Rio" in Pearls From Peoria, Subterranean Press, 2006. Croteau, Michael (1990). "Articles". The Official Philip José Farmer Web Page. Retrieved October 8, 2013.

The article begins as Phil and fellow scifi authors Alfred Bester, Arthur C. Clarke, Harlan Ellison, Harry Harrison, Sam Moskowitz, and A. E. von Vogt (sic), are getting on the plane to come home. Most of the report, which he calls a travelog of the mind, takes place on the plane ride home.

- ↑ Robert Bloch, Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorised Autobiography NY: Tor Books, 1993, p. 360

- ↑ Robert Bloch, Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorised Autobiography NY: Tor Books, 1993, pp. 360–63

- ↑ Liukkonen, Petri. "Robert Bloch". Books and Writers (kirjasto.sci.fi). Finland: Kuusankoski Public Library. Archived from the original on 10 February 2015.

- ↑ http://alangullette.com/lit/hpl/bloch.htm

- ↑ http://www.tabula-rasa.info/DarkAges/RobertBloch.html

- ↑ http://www.eeriebooks.com/horror/writers/robert-bloch/

- ↑ "Robert Bloch – Interviews". Mgpfeff.home.sprynet.com. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ Robert Bloch (1914–1994) by Frank M. Robinson Locus, No. 406, November 1994

- ↑ Robert Bloch: An Unauthorised Autobiography Tor Books, 1993, p. 88

- ↑ "Lefty Feep and I" in Bloch's Out of My Head. Cambridge MA: NESFA Press, 1986, 126.

- ↑ A Conversation with Harold Gauer by Michael G. Pfefferkorn

- ↑ Robert Bloch: An Unauthorized Autobiography Tor Book, 1993, p. 103

- ↑ Robert Bloch, Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorised Autobiography. BY: Tor Books, 1993, pp.347–49

- ↑ Arrived at by comparison of story titles listed in the Rarities: Unanthologized Stories section of Randall D. Larson, The Complete Robert Bloch: An Illustrated Comprehensive Bibliography (Fandom Unlimited, 1988) with contents of Flowers from the Moon, the three volumes of the Lost Bloch series and the two volumes of the Reader's Bloch series.

- ↑ "The Best Short Story Hugo Nominees and Winners". Web2.airmail.net. April 27, 2004. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Robert Bloch". Web2.airmail.net. May 26, 2003. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ http://www.imdb.com/event/ev0000219/1961

- 1 2 3 4 "Periodic Table of Ultimate Mystery Fiction Web Guide". Magicdragon.com. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "1975 World Fantasy Award Winners and Nominees". Worldfantasy.org. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "The Hugo Award (By Year)". Worldcon.org. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Horror Writers Association – Past Stoker Award Nominees & Winners". Horror.org. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "Horror Writers Association – Past Stoker Award Nominees & Winners". Horror.org. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ Robert Bloch on Poe and Lovecraft

- 1 2 "Horror Writers Association – Past Stoker Award Nominees & Winners". Horror.org. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ Once Around the Bloch: An Unauthorized Autobiography (1993)pp.258–62, 264–68.

- ↑ Jonathan R. Eller and William F. Toupence. Ray Bradbury: The Life of Fiction Ohio: Kent State University Press, 2004, p. 270

Sources

- Bloch, Robert (1993). Once Around the Bloch : An Unauthorized Autobiography. TOR. ISBN 978-0-312-85373-0

External links

-

Works written by or about Robert Bloch at Wikisource

Works written by or about Robert Bloch at Wikisource - Works by Robert Bloch at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Robert Bloch at Internet Archive

- Works by Robert Bloch at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- The Bat Is My Brother: The Unofficial Robert Bloch Website Note: Last updated: August 6, 2007

- Robert Bloch at DMOZ

- Robert Bloch at the Internet Speculative Fiction Database

- Robert Bloch at Find a Grave

- Robert Bloch at the Internet Movie Database

- Robert Bloch at Memory Alpha (a Star Trek wiki)

- Robert Bloch Obituary at Hitchcock wiki