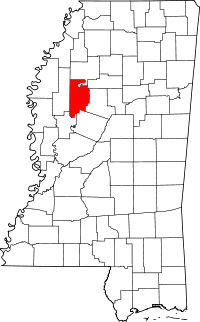

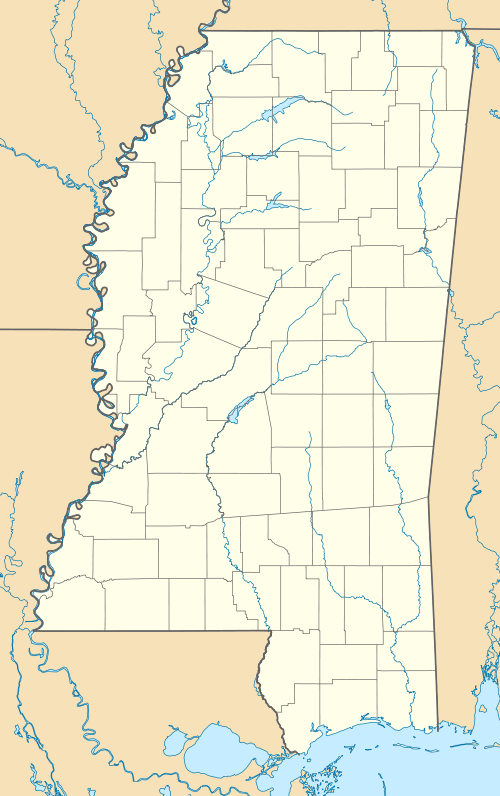

Minter City, Mississippi

| Minter City, Mississippi | |

|---|---|

| Unincorporated community | |

| |

Minter City, Mississippi  Minter City, Mississippi | |

| Coordinates: 33°45′1″N 90°17′40″W / 33.75028°N 90.29444°WCoordinates: 33°45′1″N 90°17′40″W / 33.75028°N 90.29444°W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Mississippi |

| Counties | Leflore |

| Elevation | 138 ft (42 m) |

| Time zone | Central (CST) (UTC-6) |

| • Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) |

| ZIP code | 38944 |

| Area code(s) | 662 |

| GNIS feature ID | 673683[1] |

Minter City is an unincorporated community located in Leflore County and in Tallahatchie County, Mississippi.[2] It is part of the Greenwood, Mississippi micropolitan area, and is within the Mississippi Delta.

Mississippi Highway 8 intersects U.S. Route 49E southwest of Minter City, and the Tallahatchie River flows to the east. There is a post office located on U.S. Route 49E, with a ZIP code of 38944.[3]

History

Variant names for the original settlement were "Walnut Place Landing" and "Minter City Landing".[4]

Spanish explorer Hernando de Soto may have crossed the Tallahatchie River near Minter City as his party traveled west in 1541.[5]

In 1849, James A. Towne bought 10,000 acres (4,000 ha) of land in the area at a cost of 25 cents per acre, and built a log house on the western shore of the river at Minter City. Known as "Uncle Jimmy", Towne supported the local Methodist church, and was known to give each new preacher a wagon and a mule.[6][7]

The "James Minter Ferry", documented in 1868, enabled the crossing of the Tallahatchie River at this site.[8]

Minter City became a junction for two railroads, both now abandoned. The Mobile, Jackson and Kansas City Railroad was established in 1890, and the Minter City Southern and Western Railroad, a shortline railroad servicing the sawmills west of Minter City, began operating in 1904. A depot and railroad facilities were erected in Minter City.[9]

The African-American educator William H. Holtzclaw, founder of the Utica Normal and Industrial Institute for the Training of Colored Young Men and Young Women (now part of Hinds Community College), in Utica, Mississippi, wrote about his experiences establishing schools for African-Americans in Mississippi in his book The Black Man's Burden, published in 1915. In the book, Holtzclaw describes meeting with a wealthy white plantation owner in Minter City to discuss the establishment of a school there:

I believe you are about to engage in a good work, and I would like to see the Negro educated, but, candidly, I do not think that the kind of school you would like to start would do any good in the Delta. I really think it would do harm. What I want here is Negroes who can make cotton, and they don't need education to help them make cotton. I could not use educated Negroes on my place, but since you have asked me for advice, I will tell you candidly that here in the Delta is no place to start a school.[10]

The Frank Streater Consolidated School (White) was constructed in Minter City in 1921. The abandoned building burned in 2013.[11]

Minter City was the site of a lynching in 1933. Richard Roscoe, an African-American Baptist deacon and tenant farmer, had been in a physical altercation with the white plantation manager, and both men had been injured. An hour later, Roscoe was abducted, shot dead, and then dragged through the streets of Minter city tied to the back of the sheriff's car.[12]

A large gated factory now occupies much of minter city, and there is a public boat launch.

Notable people

- L.C. Green, blues guitarist.[13]

- Lusia Harris, Olympic silver medalist and All American basketball player.[14]

- M. Carl Holman, author, poet and playwright.[15]

- Kemp Malone, linguist and literary scholar.[16]

- Willie C. Williams, actor who has appeared in The Fugitive, Flatliners, and Chain Reaction.[17]

References

- ↑ U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Minter City, Mississippi

- ↑ "Minter City". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ ZIP Code Lookup

- ↑ "Minter City Landing". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Fordyce, John (2001). O'Brien, Michael J.; Lyman, R. Lee, eds. Trailing DeSoto. Setting the Agenda for American Archaeology: The National Research Council Archaeological Conferences of 1929, 1932, and 1935. University of Alabama Press. p. 153.

- ↑ Mississippi: A Guide to the Magnolia State. Viking. 1938. p. 421.

- ↑ Fraiser, Jim (2000). Mississippi River Country Tales: A Celebration of 500 Years of Deep South History. Pelican. p. 125.

- ↑ "James Minter Ferry (historical)". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- ↑ Howe, Tony. "Minter City, Mississippi". Mississippi Rails. Retrieved March 2014. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - ↑ Holtzclaw, William H. (1915). "The Black Man's Burden". Neale.

- ↑ Baughn, Jennifer (October 22, 2008). "Frank Streater Consolidated School (White)". Mississippi Department of Archives and History.

- ↑ Finnegan, Terence (2013). A Deed So Accursed: Lynching in Mississippi and South Carolina, 1881-1940. University of Virginia Press.

- ↑ Larkin, Colin (2013). The Virgin Encyclopedia of The Blues. Random House.

- ↑ Sorensen, Dan (May 1977). "Give the Ball to Lusia". NBA.com.

- ↑ Thompson, Julius Eric (2001). Black Life in Mississippi: Essays on Political, Social, and Cultural Studies in a Deep South State. University Press of America.

- ↑ Malone, Randolph Augustus (1996). Malone and Allied Families. R.A. Malone.

- ↑ Smith, Charlie (February 6, 2010). "Prisoner Turned Actor Seeks Closure" (PDF). Greenwood Commonwealth.