History of the UK Independence Party

The UK Independence Party is a British political party, founded in 1993.

Founding and early years

UKIP was founded in 1993 by Alan Sked and other members of the cross-party Anti-Federalist League, a political party set up in November 1991 with the aim of fielding candidates opposed to the Maastricht Treaty.[1] The nascent party's primary objective was withdrawal of the United Kingdom from the European Union. It attracted a few members of the Eurosceptic wing of the Conservative Party, which was split on the European question after the pound was forced out of the European Exchange Rate Mechanism in 1992 and the struggle over ratification of the Maastricht Treaty. UKIP candidates stood in the 1997 general election, but were overshadowed by James Goldsmith's Referendum Party. (The Referendum Party contested 547 seats. In the 165 seats contested by both, the Referendum Party beat UKIP in all but two - Romsey and Glasgow Anniesland, the latter by just two votes.)[2]

After the election, Sked resigned from the leadership and left the party because, he said, it contained members who "are racist and have been infected by the far-right"[3] and was "doomed to remain on the political fringes".[4] However, Goldsmith died soon after the election and the Referendum Party was dissolved, with a resulting influx of new UKIP supporters. The leadership election was won by the millionaire businessman Michael Holmes, and in the 1999 elections to the European Parliament UKIP gained three seats and 7% of the vote. In that election, Nigel Farage (South East England), Jeffrey Titford (East of England) and Michael Holmes (South West England) were elected.

Over the following months there was a power struggle between Holmes and the party's National Executive Committee (NEC). This was partly due to Holmes making a speech perceived as calling for greater powers for the European Parliament against the European Commission. Ordinary party members forced the resignation of both Holmes and the entire NEC, and Jeffrey Titford was subsequently elected leader. After Holmes resigned from the party itself in March 2000,[5] there was a legal battle when he tried to continue as an independent MEP until he resigned from the European Parliament in December 2002. Holmes was then replaced by Graham Booth, the second candidate on the UKIP list in South West England.

UKIP put up candidates in more than 420 seats in the 2001 general election, attaining 1.5% of the vote and failing to win any representation at Westminster. It also failed to break through in the elections to the Scottish Parliament or the Welsh Assembly, despite those elections being held under proportional representation. In 2002, Titford stood down as party leader, but continued to sit as a UKIP MEP. He was replaced as leader by Roger Knapman. In 2004 UKIP reorganised itself nationally as a private company limited by guarantee, with the legal name of United Kingdom Independence Party Limited, though branches remained as unincorporated associations.[6][7]

2004 to 2012

2004 European elections and 2005 general election

In the 2004 European elections UKIP came third with 12 MEPs being elected. In the London Assembly elections the same year, UKIP won two London Assembly seats.

In late 2004, the mainstream UK press speculated on if or when the UKIP MEP, former Labour Party MP and chat-show host Robert Kilroy-Silk would take control of the party. These comments were heightened by Kilroy-Silk's speech at the UKIP party conference in Bristol on 2 October 2004, in which he called for the Conservative Party to be "killed off" following the by-election in Hartlepool, where UKIP finished third (with 10.2%) above the Conservatives in fourth (9.7%).

Interviewed by Channel 4 television, Kilroy-Silk did not deny having ambitions to lead the party, but stressed that Roger Knapman would lead it into the next general election. However, the next day, on Breakfast with Frost, he criticised Knapman's leadership.[8] After further disagreement with the leadership, Kilroy-Silk resigned the UKIP whip in the European Parliament on 27 October 2004.[9] Initially, he remained a member, while seeking a bid for the party leadership. However, this was not successful and he resigned completely from UKIP on 20 January 2005, calling it a "joke".[10] Two weeks later, he founded his own party, Veritas, taking a number of UKIP members, including both of the London Assembly members, with him.[11]

In the 2005 general election, UKIP fielded 495 candidates and gained 618,000 votes, or 2.3% of the total votes cast in the election, and did not win a seat in the House of Commons. This result placed it fourth in terms of votes cast nationally.[12] Its best performance was in Boston & Skegness, where Richard Horsnell came third with 9.6% of the vote.[13]

Following the 2005 general election, Kilroy-Silk resigned from Veritas after its performance in the election, the party having received only 40,607 votes.[12] In April 2006 David Cameron, during a phone-in on London's LBC radio station, described UKIP members as being "fruitcakes, loonies and closet racists, mostly."[14] Farage asked for an apology. but Cameron did not back down.[15] On 12 September 2006, Farage was elected leader of UKIP with 45% of the vote, 20% ahead of his nearest rival.

2009 European elections

On 28 March 2009, the Conservative Party's biggest-ever donor, Stuart Wheeler, donated £100,000 to UKIP after criticising David Cameron's stance towards the Lisbon treaty and the European Union. He said, "If they kick me out I will understand. I will be very sorry about it, but it won't alter my stance."[16] The following day, 29 March, he was expelled from the Conservative Party.[17]

The 2009 European elections resulted in UKIP coming second with 16.5% of the vote and 13 MEPs, an increase of one MEP and 0.3% in the share of the vote compared to the 2004 European Elections.[18]

2009 leadership election

In September 2009, Nigel Farage announced that he would be resigning as leader of the party in order to stand for Parliament against the Speaker, John Bercow.[19] The leadership election was contested by five candidates - Malcolm Pearson, Gerard Batten, Nikki Sinclaire, Mike Nattrass and Alan Wood - and was won by Malcolm Pearson with just under half of the 9900 votes cast [20]

2010 general election

UKIP fielded 572 candidates in the 2010 general election;.[21] The Lord Pearson of Rannoch asked some prospective candidates to stand down in favour of Eurosceptic Conservative and Labour MPs. However, some refused to do so. This did not stop Lord Pearson from campaigning on behalf of the Conservative candidates stating that he was "putting country before party". These decisions drew some criticism from within the party from the likes of Michael Heaver of Young Independence.

On the morning of polling day, Farage was injured while flying as a passenger in a light aircraft which crashed near Brackley, Northamptonshire.[22]

In the election the party polled 3.1% of the vote (919,471 votes), an increase of 0.9% on the 2005 general election, but took no seats.[23] This made it the party with the largest percentage of the popular vote to win no seats in the election.[24]

In Buckingham, the seat of the Speaker John Bercow, Farage obtained 17% of the vote, despite receiving some level of support from Lord Tebbit, a senior Conservatives figure.[25] Farage came third behind Bercow and John Stevens, the Buckinghamshire Campaign For Democracy candidate,[26] a Europhile and former Conservative MEP.[27] UKIP was also third in three other constituencies: North Cornwall, North Devon and Torridge and West Devon.[28] Farage's result was the best of all UKIP candidates that the party put forward in the 2010 general election.[29]

2010 leadership election

Lord Pearson resigned as leader in August 2010.[30] The subsequent leadership election was contested between Nigel Farage, Tim Congdon, David Bannerman and Winston McKenzie and won by Farage with more than 60% of the vote.[31] During his acceptance speech, Farage spoke out against the leadership of the Conservative Party, and Conservative policy on Europe.[32] Lord Pearson, the previous leader, welcomed Farage's re-election, and said "The UKIP crown returns to its rightful owner."[33]

2011 and 2012

UKIP contested two by-elections in early 2011, with candidate Jane Collins coming second in Barnsley Central with 12.2% of the vote[34] and Paul Nuttall finishing fourth in Oldham East and Saddleworth with 5.8% of the vote.[35]

UKIP fielded 1,217 candidates for the 2011 local council elections, a major increase over its previous campaigns, but not enough to qualify for a party election broadcast on television.[36] UKIP said that the party was well-organised in the South East, South West and Eastern regions, but there were still places across the country where there were no UKIP candidates standing at all.[37]

Across the country, many UKIP candidates came second or third. UKIP in Newcastle-under-Lyme gained a total of five seats on Newcastle Borough Council in 2007 and 2008 and three seats on Staffordshire County Council in 2009. Although UKIP did not poll well, it made gains across many parts of England, as well as taking control of Ramsey town council with nine UKIP councillors out of 17. Whilst UKIP made gains and losses, the party fell short of Farage's predictions of major gains. The UKIP MEP Marta Andreasen called for Farage's resignation as leader of the party.[38]

In the May 2012 local elections, UKIP put up 691 candidates in around 2500 local council election contests. Their average % vote share (weighted according to total votes cast) was 13%.[39][40]

In October 2012, David McNarry, a member of the Northern Ireland Assembly who had been elected as an Ulster Unionist, joined UKIP after being expelled from the Ulster Unionist Party, becoming UKIPs second representative in Northern Ireland alongside Henry Reilly, a councillor in Newry and Mourne.[41]

On 29 November 2012, UKIP finished in second place in the 2012 Rotherham by-election, with 4,648 votes (21.7% of the votes cast). This was the highest percentage share recorded by UKIP in any parliamentary election (although it had polled a greater number of votes in the 2012 Corby by-election and also in Buckingham in the 2010 general election, where its candidate was Nigel Farage).[42][43] Its candidate, Jane Collins, had previously been the only UKIP candidate to come second in any UK parliamentary election, at Barnsley Central in 2011. UKIP also came second in 2012 in the Middlesbrough by-election and third in the Croydon North by-election, which were held on the same day as Rotherham.

During 2012 and early 2013, UKIP's popularity in opinion polls increased, with many polls indicating that it had overtaken the Liberal Democrats for third place.[44]

2013 to present

.svg.png)

In the Eastleigh by-election on 28 February 2013, the UKIP candidate Diane James came second, polling the highest proportion and number of votes (27.8% and 11,571 respectively) that a UKIP parliamentary candidate had achieved to this point in time.

Local elections

UKIP put up a record number of candidates for the 2013 local elections and in the run up to the election performed well in opinion polls,[45] despite a number of controversies over individual candidates in the weeks before the elections.[46][47][48]

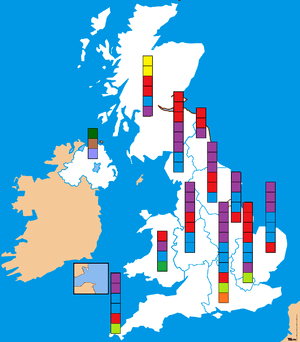

In the 2013 county council elections across England, the party achieved its best ever local government result, polling an average of 23% in the wards where it stood, and returning 147 elected councillors.[49] It made significant gains in Norfolk, Lincolnshire and Kent, taking 15, 16 and 17 seats respectively.[50] It was described as the best result for a party outside the big three in British politics since the Second World War.[51]

In local elections in 2014, UKIP won 163 seats, an increase of 128, but did not take control of any council.[52]

2014 European elections

In March 2014, Ofcom and the BBC awarded UKIP "major party status" for the 2014 European Elections.[53][54]

UKIP received the greatest number of votes (27.49%) of any British party in the 2014 European Parliament election and gained 11 extra MEPs for a total of 24.[55] The party won seats in every region of Great Britain, including its first in Scotland.[56] It was the first time in over a century that a party other than Labour or Conservatives won the most votes in a UK-wide election.[56]

Parliamentary by-elections and first elected MPs

In the Heywood and Middleton by-election, UKIP canididate John Bickley came second in the poll with 11,016 votes (38.7%), 2.2% behind the winner. The 36-point increase in UKIP support was one of the biggest increases in vote for a party in a by-election.[57]

UKIP gained its first elected MP with Douglas Carswell winning the seat of Clacton by 12,404 votes on 9 October 2014.[58] His 21,113 votes (59.75%) represented a 44% swing from the Conservative party, from whom Carswell had defected, his resignation having triggered the Clacton by-election.[58]

On 20 November 2014, Mark Reckless, who had also defected from the Conservatives and resigned his seat in order to trigger a by-election, was re-elected for UKIP in Rochester and Strood.[59]

UKIP gained its first elected MP with Douglas Carswell winning the seat of Clacton during a Clacton by-election in October 2014.[58] Carswell had defected from the Conservatives, and gained 59.75% of the vote.[58] In November fellow defector from the Conservatives, Mark Reckless, resigned his seat in order to trigger a by-election, before being re-elected for UKIP in Rochester and Strood.[59] In the 2015 general election, Carswell held his seat but Reckless lost his. UKIP's share of the vote nationally rose to 13%. Farage did not win the constituency of South Thanet and briefly resigned as leader,[60] before the party's NEC rejected his resignation and he was re-instated as party leader.[61] In the 2015 local elections held on the same day, UKIP took control of Thanet District Council.[62]

In the 2015 General Election, when the result was expected to be a hung parliament, the issue of Democratic Unionist Party (DUP, Northern Irish political party) and UKIP forming a coalition government with the Conservative Party was considered by Farage.[63][64] The then Deputy Prime Minister and leader of the Liberal Democrats, Nick Clegg, warned against this "Blukip" coalition, with a spoof website highlighting imagined policies from this coalition – such as reinstating the death penalty, scrapping all benefits for under 25s and charging for hospital visits.[65] Additionally, issues were raised about the continued existence of the BBC (as the DUP, UKIP and Conservatives had made a number of statements criticising the institution)[66] and support for LGBT rights and same-sex marriage, as the DUP are opposed to the institution[67][68] and UKIP had been involved in controversies over the alleged homophobia of its candidates in the past.[69] Although UKIP's manifesto made no mention of LGBT rights or LGBT issues, the party offered a "Christian manifesto" which opposed same-sex marriage and offered legal protection for religious opponents of same-sex marriage; however, the party said they did not wish to reverse it once it had become law.[70][71][72]

Farage resignations

In the run-up to the 2015 general election, Farage had said that he would resign as party leader if he did not win the seat of South Thanet.[73] After the election, on 8 May, Farage resigned at 11:22am saying that he is "going to take the summer off, enjoy myself a bit, not do much politics at all and there will be a leadership election for Ukip in September." He raised the possibility that he might stand in that election.[74] However, he was reinstated three days later when the party's NEC unanimously rejected his resignation.[38]

A row within the party then began over the refusal by Douglas Carswell, the party's only MP, to take the full Short money allocated to UKIP. There were subsequent briefings critical of Carswell and then, in turn, of Farage.[38] MEP Patrick O'Flynn, in particular, was critical of Farage and two of his advisers in an interview in The Times in which he described Farage as a "snarling, thin-skinned, aggressive man", although he later said he wanted Farage to stay leader. The two aides, Matthew Richardson and Farage's chief of staff, Raheem Kassam, later quit.[38] UKIP donor Stuart Wheeler said he would like Farage "to step down at least for the moment", while other sources called for a leadership contest, but Suzanne Evans, a possible successor, gave Farage her support.[38] On 14 May, Farage ruled out resigning, saying it was the wrong time for the party to have a leadership election and that he had great support within the party.[75]

Some within the party called for him to take a 'short break', including Douglas Carswell and Suzanne Evans, the latter adding that "two weeks’ holiday would be enough".[76] O'Flynn subsequently resigned from his economics role in the party, while Evans' contract for her policy role came to an end. Richardson was re-instated in June 2015.[77] No candidates declared their intention to stand during the time Farage resigned and was reinstated as leader three days later, although media speculation identified several possible candidates.[78]

Following a worse-than-expected result in the Oldham West and Royton by-election, Carswell told the BBC that the Party needs a "fresh face" as leader, and called for UKIP to become a party that is not seen as "unpleasant" and "socially illiberal".[79] As a consequence, Carswell was asked to explain himself at the Party executive committee's January 2016 meeting.[80]

In 2016 National Assembly for Wales election, UKIP nearly tripled their share of votes (from 4,7 per cent to 12,5 per cent) and won seven seats.[81] After the election, Neil Hamilton was elected leader of the UKIP group in the Assembly. UKIP also won two seats in the London Assembly, giving the party its first representation there since 2005. However, they won no seats in the Scottish Parliament, and lost the seat in the Northern Ireland Assembly that they had gained by defection, coming within 105 votes of retaining it, in East Antrim.[82] They made some gains in the local elections, increasing their councillor numbers by 25, although they came fourth on projected national vote share, behind the Liberal Democrats.

Farage resigned as UKIP leader on 4 July 2016 with the following comment, "During the [Brexit] referendum I said I wanted my country back … now I want my life back"[83] and added that this resignation was final: "I won’t be changing my mind again, I can promise you",[84] apparently referring to two previous withdrawals of his resignation (in 2009 and 2015).[85]

By 5 July 2016, some political analysts questioned how UKIP will sustain itself now that the "driving issue" (leaving the EU) was no longer relevant. An article in The Telegraph indicated that this would be "the first issue on the agenda for Farage's successor, as well as trying to influence the terms by which Britain leaves the EU."[86]

See also

References

- ↑ "About UKIP".

- ↑ Robert Ford and Matthew Goodwin, Revolt on the Right, p30 and p56. Routledge (2014)

- ↑ Cohen, Nick (6 February 2005). "Nick Cohen: No truth behind Veritas". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Scottish election: UK Independence Party profile". BBC. London. 13 April 2011.

- ↑ "Former UKIP leader quits party". BBC News. London. 21 March 2000.

- ↑ "Companies House WebCHeck - UNITED KINGDOM INDEPENDENCE PARTY LIMITED". Companies House. Company No. 05090691. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "(1) UK Independence Party Limited, (2) Gordon Howard Parkin v. Alan Hardy". Royal Courts of Justice. 26 October 2011. [2011] EWCA Civ 1204. Retrieved 13 September 2013.

- ↑ "Kilroy-Silk wants UKIP leadership", Daily Telegraph, 3 October 2004

- ↑ "Kilroy quits UKIP group of MEPs", BBC News, 27 October 2004

Matthew Tempest, "Kilroy resigns Ukip whip" Guardian online, 27 October 2004 - ↑ "Kilroy-Silk quits 'shameful' UKIP", BBC News, 21 January 2005

- ↑ Martin Hoscik, "UKIP on the London Assembly? What Farage and the Politics Show didn’t say…", MayorWatch, 23 March 2011

- 1 2 The Electoral Commission, Election 2005: constituencies, candidates and results, page 8, March 2006

- ↑ "Result: Boston & Skegness". BBC News.

- ↑ "UKIP demands apology from Cameron", BBC News, 4 April 2006

- ↑ Ros Taylor "Cameron refuses to apologise to Ukip", theguardian.com, 4 April 2006

- ↑ Coates, Sam (29 March 2009). "Tory donor Stuart Wheeler faces expulsion over UKIP support". The Times. London. Retrieved 29 March 2010.

- ↑ "UK | Tory party to expel donor Wheeler". BBC News. 29 March 2009. Retrieved 13 April 2010.

- ↑ "European Elections 2009, UK results". BBC News. 19 April 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Farage to stand against Speaker". London: BBC News. 3 September 2009.

- ↑ "Lord Pearson elected leader of UK Independence Party". BBC News. 27 November 2009. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Tories fear Ukip could cause as much harm as SDP did to Labour". The Guardian. 1 March 2013. Retrieved 30 August 2013.

- ↑ "Nigel Farage injured in plane crash on election day". BBC News. 6 May 2010. Retrieved 18 May 2010.

- ↑ "Electoral Commission website". Electoralcommission.org.uk. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- ↑ "Election 2010". BBC News. Retrieved 26 May 2010.

- ↑ "Lord Tebbit challenges backing for Speaker John Bercow". BBC News. 7 March 2010. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ Electoral Commission, 2010 UK general election results: Buckingham

- ↑ Emily Andres & Andy Dolan, "Speaker John Bercow holds off challenge from UKIP's Nigel Farage who remains in hospital after election day plane crash", Daily Mail, 7 May 2010

- ↑ Wells, Anthony. "TORRIDGE AND WEST DEVON". UK Polling Report. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ "2010 General Election Results". Electoral Commission. Retrieved 26 September 2013.

- ↑ Gabbatt, Adam (17 August 2010). "Lord Pearson stands down as Ukip leader because he is 'not much good'". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Nigel Farage re-elected to lead UK Independence Party". BBC News. 5 November 2010. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Nigel Farage returns as Ukip leader". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ Barnett, Ruth (5 November 2010). "Nigel Farage Re-Elected UKIP Party Leader". Sky News Online. Retrieved 11 December 2011.

- ↑ "Lib Dems slump to sixth as Labour win Barnsley poll". BBC News. 4 March 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Labour celebrate victory in Oldham East by-election". BBC News. 14 January 2011. Retrieved 27 August 2013.

- ↑ "Broadcasters' Liaison Group - Qualification Criteria". Broadcastersliaisongroup.org.uk. 5 May 2011. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ "English local elections: UKIP hopes to make gains". BBC News. 26 April 2011.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Call for UKIP's Nigel Farage to resign as double act turns sour". BBC News. 10 May 2011.

- ↑ Will "some other party" decide the 2015 general election? | The Information Daily

- ↑ Labour on the march, or Tories staying home? | Channel 4 news

- ↑ "McNarry joining UKIP after UUP departure". UTV News. 4 October 2012. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ Aylesburyvaledc.gov.uk Aylesbury Vale District Council

- ↑ "Election 2010:Buckingham". BBC News. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ See Opinion polling for the next United Kingdom general election for detail, including a list of every opinion poll carried out in 2012.

- ↑ "Local election 2013: Ken Clarke brands UKIP 'clowns'". BBC News. 28 April 2013. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ Kevin Schofield (27 April 2013). "Fury at UKIP 'fruit loops' being fielded at council elections". The Sun. London. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ "Crowborough UKIP election candidate in holocaust storm". The Argus. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- ↑ Duffin, Claire (5 March 2013). "Ukip candidate: 'PE prevents people becoming gay'". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- ↑ Hope, Christopher (5 May 2013). "Local elections 2013: Nigel Farage's Ukip surges to best ever showing, winning 150 seats". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ "Local Council Elections: UKIP Make Big Gains". Sky News. 4 May 2013. Retrieved 4 May 2013.

- ↑ Watt, Nicholas (3 May 2013). "Ukip will change face of British politics like SDP, says Nigel Farage". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Local elections 2014: results updated live". The Guardian. Retrieved 25 May 2014.

- ↑ Ofcom list of major parties, Ofcom, 3 March 2014

- ↑ Jason Groves (4 March 2014). "Ukip must be treated as a major party and given more airtime in run-up to Euro elections, Ofcom orders TV channels". Mail Online. London.

- ↑ "Vote 2014: UK European election results". BBC News. 26 May 2014.

- 1 2 "Farage: UKIP has 'momentum' and is targeting more victories". BBC News. 26 May 2014. Retrieved 27 May 2014.

- ↑ Clacton by-election: the UKIP bubble shows no sign of deflating yet | Prof. John Curtice, The Independent

- 1 2 3 4 "UKIP gains first elected MP with Clacton win", BBC News. Accessed 10 October 2014.

- 1 2 "Rochester: Farage looks to more UKIP gains after success", BBC News. Accessed 22 November 2014

- ↑ "Nigel Farage resigns as UKIP leader as the party vote rises". BBC News. 8 May 2015. Retrieved 8 May 2015.

- ↑ "Farage stays as UKIP leader after resignation rejected". BBC News. Retrieved 11 May 2015.

- ↑ "Ukip Takes Control of Thanet Council the Day After Nigel Farage Lost MP Bid". The Daily Telegraph. 9 May 2015. Retrieved 9 May 2015.

- ↑ Justice, Adam (18 March 2015). "General Election 2015: Ukip could form coalition with Tories and DUP". International Business Times. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Michael (5 May 2015). "Conservative Ukip coalition: what have the parties said". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Cromie, Claire (16 April 2015). "Nick Clegg warns of rightwing 'Blukip' alliance of DUP, Ukip and the Conservatives". The Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Stone, Jon (28 April 2015). "Tory coalition with DUP and Ukip could spell the end of the BBC as we know it". The Belfast Telegraph. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Dunne, Ciara (16 March 2015). "An alliance with the DUP will be a harder bargain than either Labour or the Tories think". New Statesman. Retrieved 29 March 2016.

- ↑ Stroude, Will (5 May 2015). "Owen Jones warns of 'homophobic' DUP holding influence over future government". Attitude Magazine. Retrieved 12 January 2016.

- ↑ Kevin Schofield (27 April 2013). "Fury at UKIP 'fruit loops' being fielded at council elections". The Sun. London. Retrieved 3 May 2013.

- "Crowborough UKIP election candidate in holocaust storm". The Argus. 25 April 2013. Retrieved 3 July 2013.

- Duffin, Claire (5 March 2013). "Ukip candidate: 'PE prevents people becoming gay'". Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 3 May 2013. - ↑ Smith, Lydia (5 May 2015). "Election 2015: Which parties score best on LGBT rights?". International Business Times. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Mason, Rowena (28 April 2015). "Ukip offers legal protection to Christians who oppose same-sex marriage". The Guardian. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Farage, Nigel (18 March 2014). "Nigel Farage confirms that UKIP will not campaign to abolish same-sex marriage". PinkNews. Retrieved 4 April 2016.

- ↑ Farage, Nigel (15 March 2015). "Nigel Farage: If I lose in South Thanet, it's curtains for me: I will have to quit as Ukip leader". The Telegraph. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ Bloom, Dan (8 May 2015). "52 minutes that shook Britain: Miliband, Clegg and Farage all resign in election bloodbath". Mirror. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ "UKIP's Nigel Farage rules out quitting as leader". BBC News. 15 May 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ McSmith, Andy (17 May 2015). "Nigel Farage under renewed pressure to take break from Ukip leadership". The Independent. Retrieved 17 May 2015.

- ↑ "Ex-UKIP party secretary Matt Richardson returns to role". BBC News. 16 June 2015. Retrieved 13 October 2015.

- ↑ McIntyre, Sophie (8 May 2015). "Who will be the next Ukip leader after Nigel Farage resigns?". The Independent. Retrieved 10 May 2015.

- ↑ "Douglas Carswell: UKIP needs a 'fresh face' as leader". BBC News. Retrieved 2016-02-23.

- ↑ Ross, Tim (19 December 2015). "Douglas Carswell faces showdown with Ukip chiefs over Farage leadership row". Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 23 February 2016.

- ↑ "Welsh Election 2016: Labour just short as UKIP wins seats - BBC News".

- ↑ Mason, Rowena (4 July 2016). "Nigel Farage resigns as Ukip leader after 'achieving political ambition' of Brexit". The Guardian. London, UK. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ Kennedy, Simon (4 July 2016). "Farage Resigns as UKIP Leader After Brexit Vote". Bloomberg. Bloomberg L.P. Retrieved 4 July 2016.

- ↑ "Brexit: UKIP leader Nigel Farage resigns". Al Jazeera English. Al Jazeera. 4 July 2016.

After running divisive campaign to leave the EU, Farage quits, while Britain faces economic and political challenges.

- ↑ Dunford, Daniel (5 July 2016). "Who are the favourites to be the next Ukip leader?". The Telegraph. London, UK. Retrieved 5 July 2016.