Community-acquired pneumonia

Community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) refers to pneumonia (any of several lung diseases) contracted by a person with little contact with the healthcare system. The chief difference between hospital-acquired pneumonia (HAP) and CAP is that patients with HAP live in long-term care facilities or have recently visited a hospital. CAP is common, affecting people of all ages, and its symptoms occur as a result of oxygen-absorbing areas of the lung (alveoli) filling with fluid. This inhibits lung function, causing dyspnea, fever, chest pains and cough.

CAP, the most common type of pneumonia, is a leading cause of illness and death worldwide. Its causes include bacteria, viruses, fungi and parasites.[1] CAP is diagnosed by assessing symptoms, making a physical examination and on x-ray. Other tests, such as sputum examination, supplement chest x-rays. Patients with CAP sometimes require hospitalization, and it is treated primarily with antibiotics, antipyretics and cough medicine.[2] Some forms of CAP can be prevented by vaccination and by abstaining from tobacco products.[3]

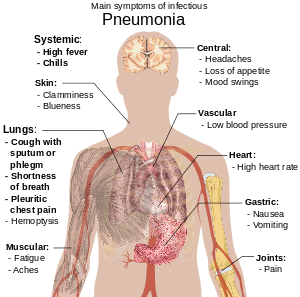

Signs and symptoms

Common symptoms

- Coughing which produces greenish or yellow sputum

- A high fever, accompanied by sweating, chills and shivering

- Sharp, stabbing chest pains

- Rapid, shallow, often-painful breathing

Less-common symptoms

- Coughing up blood (hemoptysis)

- Headaches, including migraines

- Loss of appetite

- Excessive fatigue

- Bluish skin (cyanosis)

- Nausea

- Vomiting

- Diarrhea

- Joint pain (arthralgia)

- Muscle aches (myalgia)

- Rapid heartbeat

- Dizziness or lightheadedness

In the elderly

- New or worsening confusion

- Hypothermia

- Poor coordination, leading to falls

In infants

Causes

Over 100 microorganisms can cause CAP, with most cases caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae. Certain groups of people are more susceptible to CAP-causing pathogens; for example, infants, adults with chronic conditions (such as chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), senior citizens, alcoholics and others with compromised immune systems are more likely to develop CAP from Haemophilus influenzae or Pneumocystis carinii.[5] A definitive cause is identified in only half the cases.

Infants

Infants can acquire lung infections before birth by breathing infected amniotic fluid or through a blood-borne infection which crossed the placenta. Infants can also inhale contaminated fluid from the vagina at birth. The most prevalent pathogen causing CAP in newborns is Streptococcus agalactiae, also known as group-B streptococcus (GBS). GBS causes more than half of CAP in the first week after birth.[6] Other bacterial causes of neonatal CAP include Listeria monocytogenes and a variety of mycobacteria. CAP-causing viruses may also be transferred from mother to child; herpes simplex virus (the most common) is life-threatening, and adenoviridae, mumps and enterovirus can also cause pneumonia. Another cause of CAP in this group is Chlamydia trachomatis, acquired at birth but not causing pneumonia until two to four weeks later; it usually presents with no fever and a characteristic, staccato cough.

CAP in older infants reflects increased exposure to microorganisms, with common bacterial causes including Streptococcus pneumoniae, Escherichia coli, Klebsiella pneumoniae, Moraxella catarrhalis and Staphylococcus aureus. Maternally-derived syphilis is also a cause of CAP in this age group. Viruses include human respiratory syncytial virus (RSV), human metapneumovirus, adenovirus, human parainfluenza viruses, influenza and rhinovirus, and RSV is a common source of illness and hospitalization in infants.[7] CAP caused by fungi or parasites is not usually seen in otherwise-healthy infants.

Children

Although children older than one month tend to be at risk for the same microorganisms as adults, children under five are much less likely to have pneumonia caused by Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae or Legionella pneumophila. In contrast, older children and teenagers are more likely to acquire Mycoplasma pneumoniae and Chlamydophila pneumoniae than adults.[8]

Adults

A full spectrum of microorganisms is responsible for CAP in adults, and patients with certain risk factors are more susceptible to infections of certain groups of microorganisms. Identifying people at risk for infection by these organisms aids in appropriate treatment. Many less-common organisms can cause CAP in adults, and are identified from specific risk factors or treatment failure for common causes.

Risk factors

Some patients have an underlying problem which increases their risk of infection. Some risk factors are:

- Obstruction: When part of the airway (bronchus) leading to the alveoli is obstructed, the lung cannot eliminate fluid; this can lead to pneumonia. One cause of obstruction, especially in young children, is inhalation of a foreign object such as a marble or toy. The object lodges in a small airway, and pneumonia develops in the obstructed area of the lung. Another cause of obstruction is lung cancer, which can block the flow of air.

- Lung disease: Patients with underlying lung disease are more likely to develop pneumonia. Diseases such as emphysema and habits such as smoking result in more-frequent and more-severe bouts of pneumonia. In children, recurrent pneumonia may indicate cystic fibrosis or pulmonary sequestration.

- Immune problems: Immune-deficient patients, such as those with HIV/AIDS, are more likely to develop pneumonia. Other immune problems range from severe childhood immune deficiencies, such as Wiskott–Aldrich syndrome, to the less-severe common variable immunodeficiency.[9]

Pathophysiology

CAP's symptoms are the result of lung infection by microorganisms and the immune system's response to the infection. Mechanisms of infection are different for viruses and other microorganisms.

Viruses

Viruses cause 20 percent of CAP cases. The most common viruses are influenza, parainfluenza, human respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus and adenovirus. Less-common viruses which may cause serious illness include chickenpox, SARS, avian flu and hantavirus.[10]

Typically, a virus enters the lungs through the inhalation of water droplets and invades the cells lining the airways and the alveoli. This leads to cell death; the cells are killed by the virus or they self-destruct. Further lung damage occurs when the immune system responds to the infection. White blood cells, particularly lymphocytes, activate chemicals known as cytokines which cause fluid to leak into the alveoli. The combination of cell destruction and fluid-filled alveoli interrupts the transportation of oxygen into the bloodstream. In addition to their effects on the lungs, many viruses affect other organs. Viral infections weaken the immune system, making the body more susceptible to bacterial infection (including bacterial pneumonia).

Bacteria and fungi

Although most cases of bacterial pneumonia are caused by Streptococcus pneumoniae, infections by atypical bacteria such as Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydophila pneumoniae, and Legionella pneumophila can also cause CAP. Enteric gram-negative bacteria, such as Escherichia coli and Klebsiella pneumoniae, are a group of bacteria that typically live in the large intestine; contamination of food and water by these bacteria can result in outbreaks of pneumonia. Pseudomonas aeruginosa, an uncommon cause of CAP, is a difficult bacteria to treat.

Bacteria and fungi typically enter the lungs through the inhalation of water droplets, although they can reach the lung through the bloodstream if an infection is present and often live in the respiratory tract. In the alveoli, bacteria and fungi travel into the spaces between cells and adjacent alveoli through connecting pores. The immune system responds by releasing neutrophil granulocytes, white blood cells responsible for attacking microorganisms, into the lungs. The neutrophils engulf and kill the microorganisms, releasing cytokines which activate the entire immune system. This response causes fever, chills and fatigue, common symptoms of CAP. The neutrophils, bacteria and fluids leaked from surrounding blood vessels fill the alveoli, impairing oxygen transport. Bacteria may travel from the lung to the bloodstream, causing septic shock (very low blood pressure which damages the brain, kidney, and heart).

Parasites

A variety of parasites can affect the lungs, generally entering the body through the skin or by being swallowed. They then travel to the lungs through the blood, where the combination of cell destruction and immune response disrupts oxygen transport.

Diagnosis

Patients with symptoms of CAP require evaluation. Physical examination by a health provider may reveal fever, an increased respiratory rate (tachypnea), low blood pressure (hypotension), a fast heart rate (tachycardia) and changes in the amount of oxygen in the blood. Palpating the chest as it expands and tapping the chest wall (percussion) to identify dull, non-resonant areas can identify stiffness and fluid, signs of CAP.

Listening to the lungs with a stethoscope (auscultation) can also reveal signs associated with CAP. A lack of normal breath sounds or the presence of crackles can indicate fluid consolidation. Increased vibration of the chest when speaking, known as tactile fremitus, and increased volume of whispered speech during auscultation can also indicate fluid.[11]

When signs are discovered, chest X-rays, examination of the blood and sputum for infectious microorganisms and blood tests are commonly used to diagnose CAP. Diagnostic tools depend on the severity of illness, local practices and concern about complications of the infection. All patients with CAP should have their blood oxygen monitored with pulse oximetry. In some cases, arterial blood gas analysis may be required to determine the amount of oxygen in the blood. A complete blood count (CBC) may reveal extra white blood cells, indicating infection.

Chest X-rays and X-ray computed tomography (CT) can reveal areas of opacity (seen as white), indicating consolidation. CAP does not always appear on x-rays, because the disease is in its initial stages or involves a part of the lung an x-ray does not see well. In some cases, chest CT can reveal pneumonia not seen on x-rays. X-rays can often mislead, as Heart failure or other types of lung damage can mimic CAP on x-rays.[12]

Several tests can identify the cause of CAP. Blood cultures can isolate bacteria or fungi in the bloodstream. Sputum Gram staining and culture can also reveal the causative microorganism. In severe cases, bronchoscopy can collect fluid for culture. Special tests can be performed if an uncommon microorganism is suspected, such as urinalysis for Legionella antigen in Legionnaires' disease.

Treatment

CAP is treated with an antibiotic that kills the offending microorganism and by managing complications. If the causative microorganism is unidentified (often the case), the laboratory identifies the most-effective antibiotic; this may take several days.

Health professionals consider a person's risk factors for various organisms when choosing an initial antibiotic. Additional consideration is given to the treatment setting; most patients are cured by oral medication, while others must be hospitalized for intravenous therapy or intensive care.

Therapy for older children and adults generally includes treatment for atypical bacteria: typically a macrolide antibiotic (such as azithromycin or clarithromycin) or a quinolone, such as levofloxacin. Doxycycline is the antibiotic of choice in the UK for atypical bacteria, due to increased clostridium difficile colitis in hospital patients linked to the increased use of clarithromycin.

Newborns

Most newborn infants with CAP are hospitalized, receiving IV ampicillin and gentamicin for at least ten days to treat the common causative agents streptococcus agalactiae, listeria monocytogenes and escherichia coli. To treat the herpes simplex virus, IV acyclovir is administered for 21 days.

Children

Treatment of CAP in children depends on the child's age and the severity of illness. Children under five are not usually treated for atypical bacteria. If hospitalization is not required, a seven-day course of amoxicillin is often prescribed. With the increase in drug-resistant Streptococcus pneumoniae, antibiotics such as cefpodoxime may become more popular.[13] Hospitalized children receive intravenous ampicillin, ceftriaxone or cefotaxime, and a recent study found that a three-day course of antibiotics seems sufficient for most mild-to-moderate CAP in children.[14]

Adults

In 2001 the American Thoracic Society, drawing on the work of the British and Canadian Thoracic Societies, established guidelines for the management of adult CAP dividing patients into four categories based on common organisms:[15]

- Healthy outpatients without risk factors: This group (the largest) is composed of otherwise-healthy patients without risk factors for DRSP, enteric gram-negative bacteria, pseudomonas or other, less-common, causes of CAP. Primary microoganisms are viruses, atypical bacteria, penicillin-sensitive streptococcus pneumoniae and haemophilus influenzae. Recommended drugs are macrolide antibiotics, such as azithromycin or clarithromycin, for seven[16] to ten days.

- Outpatients with underlying illness or risk factors: Although this group does not require hospitalization, patients have underlying health problems (such as emphysema or heart failure) or are at risk for DRSP or enteric gram-negative bacteria. They are treated with a quinolone active against streptococcus pneumoniae (such as levofloxacin) or a β-lactam antibiotic (such as cefpodoxime, cefuroxime, amoxicillin or amoxicillin/clavulanic acid) and a macrolide antibiotic, such as azithromycin or clarithromycin, for seven to ten days.[17]

- Hospitalized patients without risk for pseudomonas: This group requires intravenous antibiotics, with a quinolone active against streptococcus pneumoniae (such as levofloxacin), a β-lactam antibiotic (such as cefotaxime, ceftriaxone, ampicillin/sulbactam or high-dose ampicillin plus a macrolide antibiotic (such as azithromycin or clarithromycin) for seven to ten days.

- Intensive-care patients at risk for pseudomonas aeruginosa: These patients require antibiotics targeting this difficult-to-eradicate bacterium. One regimen is an intravenous antipseudomonal beta-lactam such as cefepime, imipenem, meropenem or piperacillin/tazobactam, plus an IV antipseudomonal fluoroquinolone such as levofloxacin. Another is an IV antipseudomonal beta-lactam such as cefepime, imipenem, meropenem or piperacillin/tazobactam, plus an aminoglycoside such as gentamicin or tobramycin, plus a macrolide (such as azithromycin) or a nonpseudomonal fluoroquinolone such as ciprofloxacin.

For mild-to-moderate CAP, shorter courses of antibiotics (3–7 days) seem to be sufficient.[14]

Hospitalization

Some CAP patients require intensive care, with clinical prediction rules such as the pneumonia severity index and CURB-65 guiding the decision to hospitalize.[18] Factors increasing the need for hospitalization include:

- Age greater than 65

- Underlying chronic illnesses

- Respiratory rate greater than 30 per minute

- Systolic blood pressure less than 90 mmHg

- Heart rate greater than 125 per minute

- Temperature below 35 or over 40 °C

- Confusion

- Evidence of infection outside the lung

Laboratory results indicating hospitalization include:

- Arterial oxygen tension less than 60 mm Hg

- Carbon dioxide over 50 mmHg or pH under 7.35 while breathing room air

- Hematocrit under 30 percent

- Creatinine over 1.2 mg/dl or blood urea nitrogen over 20 mg/dl

- White-blood-cell count under 4 × 10^9/L or over 30 × 10^9/L

- Neutrophil count under 1 x 10^9/L

X-ray findings indicating hospitalization include:

- Involvement of more than one lobe of the lung

- Presence of a cavity

- Pleural effusion

Prognosis

The CAP outpatient mortality rate is less than one percent, with fever typically responding to the first two days of therapy and other symptoms in the first week. However, X-rays may remain abnormal for at least a month. Hospitalized patients have an average mortality rate of 12 percent, with the rate rising to 40 percent for patients with bloodstream infections or requiring intensive care.[19] Factors increasing mortality are identical to those indicating hospitalization.

Unresponsive CAP may be due to a complication, a previously-unknown health problem, inappropriate antibiotics for the causative organism, a previously-unsuspected microorganism (such as tuberculosis) or a condition mimicking CAP (such as granuloma with polyangiitis). Additional tests include X-ray computed tomography, bronchoscopy or lung biopsy.

Complications

Major complications of CAP include:

- Sepsis, when microorganisms enter the bloodstream and the immune system responds. Sepsis often occurs with bacterial pneumonia, with streptococcus pneumoniae the most-common cause. Patients with sepsis require intensive care, with blood-pressure monitoring and support against hypotension. Sepsis can cause liver, kidney and heart damage.

- Respiratory failure: CAP patients often have dyspnea, which may require support. Non-invasive machines (such as bilevel positive airway pressure), a tracheal tube or a ventilator may be used.

- Pleural effusion and empyema: Microorganisms from the lung may trigger fluid collection in the pleural cavity. If the microorganisms are in the fluid, the collection is an empyema. If pleural fluid is present, it should be collected with a needle and examined. Depending on the results, complete drainage of the fluid with a chest tube may be necessary. If the fluid is not drained, bacteria may continue to proliferate because antibiotics do not penetrate the pleural cavity well.

- Abscess: A pocket of fluid and bacteria may be seen on an X-ray as a cavity in the lung. Abscesses, typical of aspiration pneumonia, usually contain a mixture of anaerobic bacteria. Although antibiotics can usually cure abscesses, sometimes they require drainage by a surgeon or radiologist.

Epidemiology

CAP is common worldwide, and a major cause of death in all age groups. In children, most deaths (over two million a year) occur in newborn period. According to a World Health Organization estimate, one in three newborn deaths are from pneumonia.[20] Mortality decreases with age until late adulthood, with the elderly at risk for CAP and its associated mortality.

More CAP cases occur during the winter than at other times of the year. CAP is more common in males than females, and more common in black people than Caucasians. Patients with underlying illnesses (such as Alzheimer's disease, cystic fibrosis, COPD, tobacco smoking, alcoholism or immune-system problems) have an increased risk of developing pneumonia.[21]

Prevention

CAP may be prevented by treating underlying illnesses increasing its risk, by smoking cessation and vaccination of children and adults. Vaccination against haemophilus influenzae and streptococcus pneumoniae in the first year of life has reduced their role in childhood CAP. A vaccine against streptococcus pneumoniae, available for adults, is recommended for healthy individuals over 65 and all adults with COPD, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, cirrhosis, alcoholism, cerebrospinal fluid leaks or who have had a splenectomy. Re-vaccination may be required after five or ten years.[22]

Patients who are vaccinated against streptococcus pneumoniae, health professionals, nursing-home residents and pregnant women should be vaccinated annually against influenza.[23] During an outbreak, drugs such as amantadine, rimantadine, zanamivir and oseltamivir have been demonstrated to prevent influenza.[24]

See also

References

- ↑ "Pneumonia Causes - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ↑ "Pneumonia Treatments and drugs - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ↑ "Pneumonia Prevention - Mayo Clinic". www.mayoclinic.org. Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ↑ Metlay JP, Schulz R, Li YH, et al. (July 1997). "Influence of age on symptoms at presentation in patients with community-acquired pneumonia". Archives of Internal Medicine. 157 (13): 1453–9. doi:10.1001/archinte.157.13.1453. PMID 9224224.

- ↑ "What is pneumonia? What causes pneumonia?". Retrieved 2015-05-18.

- ↑ Webber S, Wilkinson AR, Lindsell D, Hope PL, Dobson SR, Isaacs D (February 1990). "Neonatal pneumonia". Archives of Disease in Childhood. 65 (2): 207–11. doi:10.1136/adc.65.2.207. PMC 1792235

. PMID 2107797.

. PMID 2107797. - ↑ Abzug MJ, Beam AC, Gyorkos EA, Levin MJ (December 1990). "Viral pneumonia in the first month of life". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 9 (12): 881–5. doi:10.1097/00006454-199012000-00005. PMID 2177540.

- ↑ Wubbel L, Muniz L, Ahmed A, et al. (February 1999). "Etiology and treatment of community-acquired pneumonia in ambulatory children". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 18 (2): 98–104. doi:10.1097/00006454-199902000-00004. PMID 10048679.

- ↑ Mundy LM, Auwaerter PG, Oldach D, et al. (October 1995). "Community-acquired pneumonia: impact of immune status". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 152 (4 Pt 1): 1309–15. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.152.4.7551387. PMID 7551387.

- ↑ de Roux A, Marcos MA, Garcia E, et al. (April 2004). "Viral community-acquired pneumonia in nonimmunocompromised adults". Chest. 125 (4): 1343–51. doi:10.1378/chest.125.4.1343. PMID 15078744.

- ↑ Metlay JP, Kapoor WN, Fine MJ (November 1997). "Does this patient have community-acquired pneumonia? Diagnosing pneumonia by history and physical examination". JAMA. 278 (17): 1440–5. doi:10.1001/jama.278.17.1440. PMID 9356004.

- ↑ Syrjälä H, Broas M, Suramo I, Ojala A, Lähde S (August 1998). "High-resolution computed tomography for the diagnosis of community-acquired pneumonia". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 27 (2): 358–63. doi:10.1086/514675. PMID 9709887.

- ↑ Bradley JS (June 2002). "Management of community-acquired pediatric pneumonia in an era of increasing antibiotic resistance and conjugate vaccines". The Pediatric Infectious Disease Journal. 21 (6): 592–8; discussion 613–4. doi:10.1097/00006454-200206000-00035. PMID 12182396.

- 1 2 Dimopoulos G, Matthaiou DK, Karageorgopoulos DE, Grammatikos AP, Athanassa Z, Falagas ME (2008). "Short- versus long-course antibacterial therapy for community-acquired pneumonia : a meta-analysis". Drugs. 68 (13): 1841–54. doi:10.2165/00003495-200868130-00004. PMID 18729535.

- ↑ Niederman MS, Mandell LA, Anzueto A, et al. (June 2001). "Guidelines for the management of adults with community-acquired pneumonia. Diagnosis, assessment of severity, antimicrobial therapy, and prevention". American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine. 163 (7): 1730–54. doi:10.1164/ajrccm.163.7.at1010. PMID 11401897.

- ↑ Li JZ, Winston LG, Moore DH, Bent S (September 2007). "Efficacy of short-course antibiotic regimens for community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis". The American Journal of Medicine. 120 (9): 783–90. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.04.023. PMID 17765048.

- ↑ Vardakas KZ, Siempos II, Grammatikos A, Athanassa Z, Korbila IP, Falagas ME (December 2008). "Respiratory fluoroquinolones for the treatment of community-acquired pneumonia: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials". CMAJ. 179 (12): 1269–77. doi:10.1503/cmaj.080358. PMC 2585120

. PMID 19047608.

. PMID 19047608. - ↑ Fine MJ, Auble TE, Yealy DM, et al. (January 1997). "A prediction rule to identify low-risk patients with community-acquired pneumonia". The New England Journal of Medicine. 336 (4): 243–50. doi:10.1056/NEJM199701233360402. PMID 8995086.

- ↑ Woodhead MA, Macfarlane JT, McCracken JS, Rose DH, Finch RG (March 1987). "Prospective study of the aetiology and outcome of pneumonia in the community". Lancet. 1 (8534): 671–4. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(87)90430-2. PMID 2882091.

- ↑ Garenne M, Ronsmans C, Campbell H (1992). "The magnitude of mortality from acute respiratory infections in children under 5 years in developing countries". World Health Statistics Quarterly. 45 (2–3): 180–91. PMID 1462653.

- ↑ Almirall J, Bolíbar I, Balanzó X, González CA (February 1999). "Risk factors for community-acquired pneumonia in adults: a population-based case-control study". The European Respiratory Journal. 13 (2): 349–55. doi:10.1183/09031936.99.13234999. PMID 10065680.

- ↑ Butler JC, Breiman RF, Campbell JF, Lipman HB, Broome CV, Facklam RR (October 1993). "Pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine efficacy. An evaluation of current recommendations". JAMA. 270 (15): 1826–31. doi:10.1001/jama.270.15.1826. PMID 8411526.

- ↑ Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (April 1999). "Prevention and control of influenza: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP)". MMWR Recomm Rep. 48 (RR–4): 1–28. PMID 10366138.

- ↑ Hayden FG, Atmar RL, Schilling M, et al. (October 1999). "Use of the selective oral neuraminidase inhibitor oseltamivir to prevent influenza". The New England Journal of Medicine. 341 (18): 1336–43. doi:10.1056/NEJM199910283411802. PMID 10536125.

- Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, et al. (March 2007). "Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults". Clinical Infectious Diseases. 44 (Suppl 2): S27–72. doi:10.1086/511159. PMID 17278083.