Timeline of malaria

For a comprehensive treatment of the subject, see History of malaria.

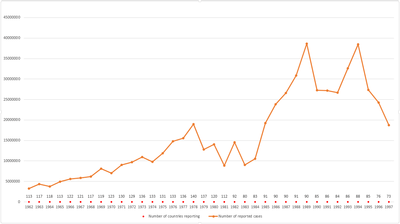

Malaria is an infectious disease caused by a parasite, it is spread by the bite of an infected mosquito. Every year, 300 to 700 million people get infected. Malaria kills 1 million to 2 million people every year. 90% of the deaths occur in Africa.[1]

Chronology

| Year/period | Event |

|---|---|

| Prehistory (from Jurassic period to Paleolithic) | The origin of malaria dates back to a very early time in a warm and humid Africa, being present long before the whole timeline of development of apes. However, it wouldn't infect humans until much later after the Upper Paleolithic, when sizable groups of humans facilitate the spread of the disease.[2] |

| Ancient history | Through Ancient Egypt and Middle East, malaria spreads further and is recognized in ancient Greece and the Roman Empire. It is implied in the decline of some great civilizations. Malaria also spreads into India and China, where real treatments begin to merge.[2] |

| Middle Ages | In Europe, witchcraft and astrology thrive around the treatment during this period.[3] Malaria is attributed to a 'bad air', hence the term mal aria (from Medieval Italian) |

| 1600s | Malaria reaches the Americas through Spanish colonization. The native population in Peru makes use of bark of the cinchona tree for treating fever.[4] After its discovery by the Spanish, the bark is brought to Europe where it comes into general use.[4][5] [6][7] |

| 1700s | The cinchona bark from South America is established as a major cure for fever.[8] |

| 1800s | Parasites are first identified as source of malaria. First drugs are developed. |

| 1900s | First antibiotics. Increasing scientific research leads to rapid advance of drugs and modern treatments. Successful eradications take place in this period. |

| 1940s–1950s | Eradication of malaria in Europe and North America becomes successful, mainly due to the massive use and proven effect of insecticide DDT.[9][10] |

| 1970s–1990s | The malaria situation deteriorates in the 70s. Reduced control measures between 1972 and 1976, due to financial constraints, lead to a massive 2-3 fold increases in malaria cases at a global level. Concerns about the potential harmful side-effects of insecticide DDT provoke its ban across many countries, raising controversy and an arguably huge number of preventable deaths in the developing world.[11][12] |

| 1990s–2000s | The World Health Organization starts to investigate artemisinin and its derivatives, finally promoting them on a large scale in the 2000s.[13] |

| 2000–2015 | Malaria incidence among populations at risk (the rate of new cases) falls by 37% globally.[1] |

Full timeline

Malaria deaths per WHO region for period between 2000 and 2015.[16] All regions but South–East Asia show negligible levels compared to Africa, where the vast majority of malaria deaths occur. Cumulative.

| Year | Event type | Event | Geographic location |

|---|---|---|---|

| 150,000,000 BC | Origin | Probable origin of malaria during the Jurassic; at this time malaria infects reptiles.[2] | Africa |

| 8000 BC | Disease spread | Malaria starts to infect people, as the first big groups of population emerge.[2] | Africa |

| 2700 BC | Publication | Chinese text Nei Ching (The Canon of Medicine) is published. It describes several characteristic symptoms of what would later be named malaria.[17] | China |

| 2000–1500 BC | Science development (symptoms) | Sumerian and Egyptian doctors describe symptoms resembling those of malaria.[2] | Middle East |

| 800 BC | Science development (vector) | Indian surgeon Sushruta indicates that malaria is caught from insect bites.[2] | |

| 340 | Science development (treatment) | The anti-fever properties of artemisinin are first described by Chinese official Ge Hong of the Jìn Dynasty.[18] | China |

| 1031–1095 | Science development (treatment) | Chinese polymath Shen Kuo suggests that plant specie artemisia apiacea has striking antimalarial properties.[13] | China |

| 1000–1500 | Disease spread | Malaria reaches northern Europe.[2] | Europe |

| 1632 | Jesuit missionary Bernabé Cobo brings cinchona bark from Perú to Spain.[18][19] | ||

| 1633 | Science development (treatment) | Jesuit priest Antonio de la Calancha writes in his Chronicle of St Augustine about a "tree which they call the fever tree whose bark made into a powder amounting to the weight of two small silver coins and given as a beverage, cures the fevers and the tertians" (being Tertians the name for the three-day cycle of one form of malarial fever).[20] | South America |

| 1649 | Publication | The Schedula Romana is released. It is considered an early example of efficient anti-malaria recipe (using cinchona bark). The publication by Pietro Paolo Puccerini is attributed to the knowledge of Spanish cardinal Juan de Lugo and to have summarized trials that Lugo probably carried out.[8] | Italy (Rome) |

| 1663 | Publication | Italian physician Sebastiano Baldi writes the first compilation of the use of cinchona bark. His work is subsequently researched by numerous authors.[8] | |

| 1712 | Science development (treatment) | Italian physician Francesco Torti writes Therapeutice Specialis, where he describes the therapeutic properties of the bark.[21] | |

| 1717 | Science development (vector) | Epidemiologist Giovanni Maria Lancisi publishes De noxiis paludum e zuviis, eorumque remediis where he suggests the possible role of mosquitoes in the transmission of malaria. Lancisi relates the prevalence of malaria in swampy areas to the presence of flies and recommends swamp drainage to prevent it.[22] | Italy |

| 1821 | Science development (treatment) | French pharmacist Joseph Bienaimé Caventou and chemist Pierre Joseph Pelletier purify quinine (obtained from the cinchona tree) and other cinchona alkaloids. The quinine molecule is promptly tested in patients, and after numerous medical observations and case reports from all over the world, it is soon indicated that quinine is specific for ‘malarial’ (intermittent) fevers.[8] | France (Paris) |

| 1874 | Science development (prevention) | German chemistry student Othmar Zeidler is credited with the first synthesis of DDT (Dichloro Diphenyl Trichloroethane). DDT is used in the second half of World War II to control malaria and typhus among civilians and troops. After the war, DDT is also used as an agricultural insecticide.[23] | |

| 1880 | Science development (parasite) | Charles Louis Alphonse Laveran observes parasites inside the red blood cells of infected people for the first time, proposing that malaria is caused by an organism. For this he receives the Nobel Prize in 1907.[24] | Algeria |

| 1881 | Science development (vector) | Carlos Finlay provides strong evidence that a mosquito later designated as Aedes aegypti transmits disease to and from humans.[25][26] The theory remains controversial for twenty years until confirmed in 1901 by Walter Reed.[27] | Cuba |

| 1886 | Science development (symptoms) | Italian neurophysiologist Camillo Golgi shows that there are at least two forms of malaria, one with tertian periodicity (fever every other day) and one with quartan periodicity (fever every third day). Golgi also observes that the two forms produce differing numbers of merozoites (new parasites) upon maturity and that fever coincide with the rupture and release of merozoites into the blood stream. Camillo Golgi is awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1906.[19][17] | |

| 1890 | Science developent (parasite) | Italian physicians Giovanni Batista Grassi and Raimondo Feletti first introduce the names plasmodium vivax and plasmodium malariae for two of the malaria parasites that affect humans.[17] | |

| 1895–1898 | Science development (vector) | British medical doctor Ronald Ross proves that malaria is transmitted by mosquitoes, and lays the foundation for the method of combating the disease. For this he receives the Nobel Prize in 1902.[24] | India |

| 1897 | Science development (parasite) | American bacteriologist William H. Welch names the malignant tertian malaria parasite plasmodium falciparum.[17] | |

| 1898 | Science development (vector) | An italian team of scientists prove that anopheles claviger mosquitoes infect humans via the bite.[28] | Italy (Rome) |

| 1903 | Organization | The American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene is founded. Today it operates worldwide, yet it remains focused on developed countries. Research, health care and education are its main activities.[29] | United States (Philadelphia). Serves worldwide. |

| 1908 | Science development (treatment) | German chemist Paul Rabe provides the first evidence for the structure of quinine.[20][30] | Germany (Hamburg) |

| 1913 | Organization | The Rockefeller Foundation is created, and through one of its branches, the International Health Division, it starts to conduct campaigns against malaria, in addition to yellow fever and hookworm.[31] | United States (New York City) |

| 1922 | Science development (parasite) | British parasitologist John William Watson Stephens describes the fourth human malaria parasite, plasmodium ovale.[17] | |

| 1931 | Science development (parasite) | British parasitologist Robert Knowles and Bengali parasitologist Biraj Mohan Das Gupta first describe plasmodium knowlesi ( a primate malaria parasite commonly found in Southeast Asia).[17] | |

| 1934 | Science development (prevention) | German scientist Hans Andersag discovers chloroquine at Bayer I.G. Farbenindustrie A.G. laboratories. By 1946 chloroquine is finally recognized and established as an effective and safe antimalarial.[17] | Germany (Elberfeld) |

| 1939 | Science development (prevention) | Organochloride DDT's insecticidal properties are discovered by Paul Hermann Müller, who is awarded the 1948 Nobel Prize in Physiology and Medicine.[32] In the following decades, total eradication of malaria is achieved in most of the developed world due to massive agricultural application of DDT.[33][9] | Europe, North America |

| 1940 | Achievement | Complete eradication of A. gambiae from northeast Brazil and thus from the New World is achieved by the systematic application of the arsenic-containing compound Paris green to breeding places, and of pyrethrum spray-killing to adult resting places.[34] | Brazil |

| 1942 | Organization | The Office of Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA) is established with the purpose of limiting the impact of malaria and other vector-borne diseases (such as murine typhus) during World War II around military training bases in the southern United States and its territories, where malaria is still problematic at the time.[35] | United States |

| 1944 | Science development (treatment) | Chemists at Imperial Chemical Industries discover antimalarial proguanil.[36] | United Kingdom |

| 1946 | Science development (treatment) | Camoquin is made available as new antimalarial drug. It is proved to be effective after administration of a single therapeutic dose.[37][18] | |

| 1947 | Program launch | In the United States, the National Malaria Eradication Program (NMEP) is launched in July. Prior to the launch of this program, malaria is an endemic across the United States, concentrated in the southeastern states. This federal program would successfully eradicate malaria in the United States by 1951.[34][38] | United States |

| 1948 | Science development (parasite) | Belgian physician Ignace Vinke and entomologist Marcel Lips identify and isolate malaria parasite plasmodium berghei from wild rodents in Central Africa.[28][39] | |

| 1948 | Science development (parasite) | Anglo-Indian protozoologist Henry Edward Shortt and British biologist Cyril Garnham discover that malaria parasites develop in the liver before entering the blood stream.[28] | |

| 1948 | Organization | The World Health Organization (WHO) forms.[40] | Switzerland (Geneva). Operates worldwide. |

| 1950 | Science development (treatment) | Primaquine is introduced as new antimalarial drug. It is proven to prevent relapse and sterilizes infectious sexual plasmodia.[41] | |

| 1952 | Science development (prevention) | Dr. Mario Pinotti introduces the strategy of putting chloroquine into common cooking salt for malaria suppression, as a way of distributing the drug as a prophylactic on a wide scale. This program (using either chloroquine or pyrimethamine) becomes known as "Pinotti's method" and is employed in South America as well as Asia and Africa.[21][42] | Brazil |

| 1955 | Organization | WHO launches the Malaria Eradication Programme. The global malaria eradication campaign is adopted by the 8th World Health Assembly and based upon the widespread use of DDT against mosquitos and of antimalarial drugs to treat malaria and eliminate the parasite in humans. Within the next decade, this program succeeds in eradicating malaria from the developed world.[43][34] | Worldwide |

| 1955–1972 | Achievement | Bulgaria, Cyprus, Dominica, Grenada, Hungary, Italy, Jamaica, Netherlands, Poland, Romania, Saint Lucia, Spain, Taiwan, Trinidad and Tobago, United States and Venezuela are certified as malaria–free by the WHO within this period.[44] | |

| 1962 | Publication | Rachel Carson publishes the science book Silent Spring which talks about the detrimental effects of the use of pesticides on the environment. The book has a massive impact in international politics, thus provoking the ban of insecticide DDT in many countries during the following decades. Carson continues to be criticized today by some who argue that such restrictions have caused tens of millions of needless deaths.[45][46][47] | |

| 1965 | Science development (parasite) | The first human infection with plasmodium knowlesi is documented.[17] | |

| 1967 | Achievement | Malaria is eradicated from all developed countries where the disease was endemic and large areas of tropical Asia and Latin America are freed from the risk of infection.[43] | |

| 1967–1981 | Organization | The secret military Project 523 of the People's Republic of China is aimed at finding new drugs for malaria. Over 500 Chinese scientists are recruited. The project leads to the discovery of artemisinin and derivatives,[48] also pyronardine, lumefantrine and naphthoquine. All these antimalarial drugs are used today in therapy.[49] | China, Vietnam |

| 1970 | Organization | Population Services International is created as a nonprofit global health organization with programs targeting malaria, child survival, HIV, and reproductive health. PSI provides life-saving products, clinical services and behavior change communications.[50][51][52] | United States (Washington, D.C.). Operates worldwide. |

| 1971 | Science development (prevention) | Antimalarial mefloquine (sold under the brand names Lariam) is first synthesized at the Experimental Therapeutics Division of the Walter Reed Army Institute of Research (WRAIR). It is number 142,490 of over 500,000 chemical compounds investigated by the United States Armed Forces to combat the devastating consequences of malaria in Vietnam.[53] Mefloquine comes into use in the mid 1980s.[54] | United States |

| 1971 | Science development (treatment) | Chinese scientists isolate the active ingredient of traditional Chinese medical drug qinghao (the blue-green herb) by extracting the artemisinin.[13][18] | China |

| 1972 | Policy | Insecticide DDT is banned in the United States. Many other countries follow suit.[33] | United States |

| 1972–1987 | Achievement | Australia, Brunei, Cuba, Mauritius, Portugal, Réunion, Singapore and Yugoslavia are certified as malaria–free by the WHO within this period.[44] | |

| 1974 | Achievement | Malaria is eradicated from 37 countries mainly in Europe and Americas.[55] | |

| 1983 | Policy | Insecticide DDT is banned in Thailand.[56] | Thailand |

| 1986 | Policy | DDT is outlawed in the United Kingdom.[57] | United Kingdom |

| 1987 | Science development (prevention) | Colombian biochemist Manuel Elkin Patarroyo develops the first synthetic vaccine against P. falciparum, the parasite that causes malaria.[24] | Colombia |

| 1992 | Organization | Malaria Foundation International (MFI) is founded as a non-profit organization dedicated to the fight against malaria. The MFI’s goals are to support awareness, education, training, research, and leadership programs to develop and apply tools to combat the disease.[58] | |

| 1992 | Policy | Insecticide DDT is banned in Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.[56] | Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam |

| 1992 | Program launch | New Global Malaria Control Strategy is launched. Endorsed by a ministerial conference on malaria control, it is later confirmed by the World Health Assembly in 1993. This new strategy is based largely upon the primary health care approach and requires flexible, cost-effective, sustainable, and decentralized programs based upon disease rather than parasite control, adapted to local conditions and responding to local needs. This approach becomes succesful and has positive impact in a number of countries such as Brazil, China, Solomon Islands, Philippines, Vanuatu, Vietnam, and Thailand. Its success demonstrates that malaria can be controlled by locally and currently available tools.[43] | Worldwide |

| 1997 | Organization | Multilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM), an alliance of organizations that facilitates research on malaria, is established. MIM would also collaborate with the Disease Control Priorities Project.[59][60] | |

| 1998 | Organization | Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center (MR4) is launched to provide resources like malaria reagents, protocols and technical support to the international research community. It is funded by the (NIAID).[61] | |

| 1998 | Organization | Global framework Roll Back Malaria Partnership is launched as a partnership between WHO, UNICEF, UNDP and the World Bank, with the purpose of coordinating action against malaria.[62] In 2015 RBM launched a Global Call to Action to increase coverage with preventive treatment to protect pregnant women from the devastation caused by malaria during pregnancy.[63] | |

| 1983 | Policy | Insecticide DDT is banned in Malaysia.[56] | Malaysia |

| 1999 | Program launch | The Research Initiative on Traditional Antimalarial Methods (RITAM) is launched as a collaboration between WHO, the Global Initiative for Traditional Systems of Health (GIFTS), the University of Oxford, and researchers and others throughout the world who are investigating or interested in the antimalarial properties of plants, with the purpose of developing or validating local herbal medicines to prevent and/or treat malaria.[64] | Tanzania (Moshi) (inaugural meeting) |

| 1999 | Organization | Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV) is founded to reduce the burden of malaria by facilitating the discovery, development, and delivery of antimalarial medicines.[65][66] The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation would be one of its major funders in subsequent years,[67] and it would partner with drug company Novartis.[68] | Switzerland (Geneva) |

| 2000 | Organization | Africa Fighting Malaria is founded as an NGO. It conducts research into the social and economic aspects of malaria.[69] | South Africa |

| 2000 | Organization | The Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation is founded by Bill and Melinda Gates with the aims of enhancing healthcare and reduce extreme poverty at a global level. Today it is the largest private foundation in the world, having donated over one billion dollars on malaria alone.[70][71] | United States (Seattle). Operates worldwide. |

| 2000 | Science development (treatment) | Roll Back Malaria Partnership launches new artemisinin combination therapy ACT.[18][72] | |

| 2001 | Policy | DDT is banned as a pesticide worldwide under the Stockholm Convention on Persistent Organic Pollutants after it is discovered to be dangerous to wildlife and the environment.[57] | Sweden (Stockholm), worldwide |

| 2001 | Organization | The Amazon Malaria Initiative is launched with the goal of preventing and controlling malaria in the Amazon basin. With support from the U.S. Agency for International Development, it has expanded into eleven countries.[73] | Brazil, Colombia, Ecuador, Guyana, Peru, Suriname, Bolivia, Venezuela (ceased participation), Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, and Panama. |

| 2002 | Organization | The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria is founded as an international financing institution dedicated to attract and fund additional resources to stop and treat those diseases.[74] | Switzerland (Geneva) |

| 2002 | Organization | The African Malaria Network Trust (AMANET) is established. Its main goal is vaccine development, although it has expanded its aims, including other intervention measures such as antimalaria drugs and vector control.[75] | Tanzania (Dar es Salaam). Operates in Africa. |

| 2003 | Organization | The Malaria Consortium is founded as a non-profit organization dedicated to the control of malaria.[76] | United Kingdom (London). Operates in Africa and Asia. |

| 2004 | Organization | Against Malaria Foundation is set up with the aim of handling money and raising funds. Much of the funds raised by it are used to purchase bednets. GiveWell, an independent charity evaluator, names AMF its top-rated charity worldwide in 2011, 2012, 2014 and 2015, and recommends to donors to donate exclusively to AMF in 2015 due to its large funding gap.[77] | United Kingdom (London). Operates in Africa. |

| 2004 | Organization | Malaria World is founded with the aim of facilitating free and unrestricted access to information on malaria.[78] | United States (Washington, DC.) |

| 2005 | Organization | South African Malaria Initiative is launched with aims at finding new ways to prevent and treat malaria.[79] | South Africa |

| 2005 | Organization | The Innovative Vector Control Consortium is established as a research consortium. It focuses on the development of new insecticides for public health vector control and also information systems and tools in order to enable new and existing pesticides to be used more effectively.[80] | United Kingdom, United States, South Africa |

| 2006 | Organization | Malaria No More is founded. It has partnerships and focuses in advocacy to elevate malaria on the global health agenda.[81] | United States (Seattle). Operates worldwide. |

| 2006 | Organization | The United Nations Foundation creates the Nothing But Nets campaign to prevent malaria deaths by purchasing, distributing, and teaching the proper use of mosquito bed nets.[82] | Sub-Saharan Africa |

| 2007–2015 | Achievement | Armenia, Maldives, Morocco, Turkmenistan and the United Arab Emirates are certified as malaria–free by the WHO within this period.[44] | |

| 2008 | Organization | The The Millennium Foundation for Innovative Finance for Health is established. Its project MassiveGood is meant to collect funds for combating HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.[83] | United States, United Kingdom, Germany, Austria, Switzerland and Spain. Serves worldwide. |

| 2008 | Program launch | The United Methodist Church launches comprehensive anti-malaria campaign Imagine No Malaria, with aims at raising $75 million "to empower the people of Africa to overcome malaria’s burden".[84] | United States |

| 2009 | Organization | The African Leaders Malaria Alliance (ALMA) is founded by African Heads of State to use their individual and collective power to keep malaria high on the political and policy agenda.[85] | Africa |

| 2012 | Organization | The Malaria Eradication Scientific Alliance (MESA) is formed to conduct research on malaria elimination.[86] | Spain |

| 2014 | Organization | EVIMalaR is conducted as a malaria research network. Funded by the European Commission and involving at least 62 partners from 51 institutes.[87] | Europe, Africa, India and Australia. |

| 2013–2015 | Organization | Dundee University establishes a center for development of drugs. A new anti-malaria drug is obtained.[88][89] | United Kingdom (Dundee) |

See also

References

- 1 2 "Malaria Fact sheet N°94". WHO. Retrieved 2 February 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "Malaria History".

- ↑ Hempelmann E, Krafts K (2013). "Bad air, amulets and mosquitoes: 2,000 years of changing perspectives on malaria" (PDF). Malar J. 12 (1): 213. doi:10.1186/1475-2875-12-232. PMC 3723432

. PMID 23835014.

. PMID 23835014. - 1 2 Butler AR, Khan S, Ferguson E (2010). "A brief history of malaria chemotherapy" (PDF). J R Coll Physicians Edinb. 40 (2): 172–7. doi:10.4997/JRCPE.2010.216. PMID 20695174.

- ↑ Bruce-Chwatt LJ (1988). "Three hundred and fifty years of the Peruvian fever bark". Br Med J (Clin Res Ed). 296 (6635): 1486–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.296.6635.1486. PMC 2546010

. PMID 3134079.

. PMID 3134079. - ↑ De Castro MC, Singer BH (2005). "Was malaria present in the Amazon before the European conquest? Available evidence and future research agenda". J Achaeol Sci. 32 (3): 337–340. doi:10.1016/j.jas.2004.10.004.

- ↑ Yalcindag E, Elguero E, Arnathau C, Durand P, Akiana J, Anderson TJ, Aubouy A, Balloux F, Besnard P, Bogreau H, Carnevale P, D'Alessandro U, Fontenille D, Gamboa D, Jombart T, Le Mire J, Leroy E, Maestre A, Mayxay M, Ménard D, Musset L, Newton PN, Nkoghé D, Noya O, Ollomo B, Rogier C, Veron V, Wide A, Zakeri S, Carme B, Legrand E, Chevillon C, Ayala FJ, Renaud F, Prugnolle F (2011). "Multiple independent introductions of Plasmodium falciparum in South America". PNAS. 109 (2): 511–6. Bibcode:2012PNAS..109..511Y. doi:10.1073/pnas.1119058109. PMC 3258587

. PMID 22203975.

. PMID 22203975. - 1 2 3 4 "Evaluation of Cinchona bark in the 17th and 18th centuries". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 de Zulueta J (June 1998). "The end of malaria in Europe: an eradication of the disease by control measures". Parassitologia. 40 (1-2): 245–6. PMID 9653750.

- ↑ "CDC - Malaria - About Malaria - History - Elimination of Malaria in the United States (1947-1951)".

- ↑ "Malaria: Past and Present". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Souder, William (September 4, 2012). "Rachel Carson Didn't Kill Millions of Africans". Slate. Retrieved September 5, 2012.

- 1 2 3 "Reflections on the 'discovery' of the antimalarial qinghao". doi:10.1111/j.1365-2125.2006.02673.x. PMC 1885105

. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

. Retrieved 25 November 2016. - ↑ "Weekly epidemiological record" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "World health statistics annual" (PDF). Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- ↑ "Deaths Due to Malaria". Retrieved 18 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "The History of Malaria, an Ancient Disease". Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Saga of Malaria Treatment". Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- 1 2 Parker, Steve. Kill or Cure: An Illustrated History of Medicine. Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Jesuits' powder". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- 1 2 Rosenthal, Philip J. Antimalarial Chemotherapy: Mechanisms of Action, Resistance, and New ... Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Cook GC, Webb AJ (2000). "Perceptions of malaria transmission before Ross' discovery in 1897" (PDF). Postgrad Med J. 76 (901): 738–40. doi:10.1136/pmj.76.901.738. PMC 1741788

. PMID 11060174. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

. PMID 11060174. Retrieved 25 November 2016. - ↑ Eckinger, Julie. The Ethics of Intensification: Agricultural Development and Cultural Change. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Journey of Scientific Discoveries".

- ↑ "Carlos Juan Finlay: Rejected, Respected, and Right". doi:10.1097/EDE.0b013e3181c308e0. Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ Finlay CJ. (1881). "El mosquito hipotéticamente considerado como agente de transmision de la fiebre amarilla". Anales de la Real Academia de Ciencias Médicas Físicas y Naturales de la Habana (18): 147–169.

- ↑ Reed W, Carroll J, Agramonte A (1901). "The Etiology of Yellow Fever". JAMA. 36 (7): 431–440. doi:10.1001/jama.1901.52470070017001f.

- 1 2 3 "History of the discovery of the malaria parasites and their vectors". doi:10.1186/1756-3305-3-5. PMC 2825508

. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

. Retrieved 24 November 2016. - ↑ "American Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Quinine". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "Rockefeller Foundation".

- ↑ NobelPrize.org: The Nobel Prize in Physiology of Medicine 1948, accessed July 26, 2007.

- 1 2 "DDT: From miracle chemical to banned pollutant". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 "WHO in 60 years: a chronology of public health milestones" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved April 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Elimination of Malaria in the United States (1947 — 1951)". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Rappoport, Zvi. The Chemistry of Anilines, Part 1. Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Camoquin". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ Horton, Richard (February 24, 2011). "Stopping Malaria: The Wrong Road". The New York Review of Books. Retrieved June 14, 2016.

- ↑ Vanderberg, Jerome P. "Reflections on Early Malaria Vaccine Studies, the First Successful Human Malaria Vaccination, and Beyond". doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2008.10.028. PMC 2637529

.

. - ↑ Markel, Howard (January 7, 2014). "Worldly approaches to global health: 1851 to the present" (PDF). Retrieved April 5, 2016.

- ↑ "Primaquine Therapy for Malaria" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Interruption of Malaria Transmission by Chloroquinized Salt in Guyana" (PDF). Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 Trigg, PI; Kondrachine, AV. "Commentary: malaria control in the 1990s.". PMC 2305627

. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

. Retrieved 24 November 2016. - 1 2 3 "Malaria Free countries". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ Lytle 2007, p. 217

- ↑ Baum, Rudy M. (June 4, 2007). "Rachel Carson". Chemical and Engineering News. American Chemical Society. 85 (23): 5.

- ↑ "Controversy".

- ↑ Dondorp, Arjen M.; Day, Nick P.J. (2007). "The treatment of severe malaria". Transactions of the Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene. 101 (7): 633–634. doi:10.1016/j.trstmh.2007.03.011. PMID 17434195.

- ↑ Cui, Liwang; Su, Xin-zhuan (2009). "Discovery, mechanisms of action and combination therapy of artemisinin". Expert Review of Anti-infective Therapy. 7 (8): 999–1013. doi:10.1586/eri.09.68. PMC 2778258

. PMID 19803708.

. PMID 19803708. - ↑ "PSI at a Glance". Population Services International. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Population Services International: Funding Growth". Bridgespan Group. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Population Services International (PSI)". GiveWell. February 1, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "The Strange History of Lariam". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ Croft, Ashley M. "A lesson learnt: the rise and fall of Lariam and Halfan". doi:10.1258/jrsm.100.4.170. PMC 1847738

. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

. Retrieved 24 November 2016. - ↑ Recent advances in pediatrics. Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 "DDT". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Banned pesticide DDT may raise risk of Alzheimer's disease". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Against Malaria Foundation Charity In Stone Mountain Georgia". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "About MIM". Multilateral Initiative on Malaria. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Multilateral Initiative on Malaria (MIM)". World Health Organization. Retrieved May 19, 2016.

- ↑ "Malaria Research and Reference Reagent Resource Center". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Roll Back Malaria". Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "Africa: Roll Back Malaria Partnership Launches Global Call to Action to Increase Coverage of Preventive Treatment for Malaria During Pregnancy Throughout Sub-Saharan Africa.". Retrieved 23 November 2016.

- ↑ "Essential Medicines and Health Products Information Portal". Retrieved 29 November 2016.

- ↑ "About us". Medicines for Malaria Venture. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Medicines for Malaria Venture (MMV)" (PDF). World Health Organization. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Gates Foundation Commits $258.3 Million for Malaria Research and Development". Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. October 1, 2015. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Novartis expands partnership with Medicines for Malaria Venture to develop next-generation antimalarial treatment". June 15, 2016. Retrieved September 2, 2016.

- ↑ "Africa Fighting Malaria". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ The Challenge of Global Health Foreign Affairs, January/February 2007

- ↑ Donald G. McNeil Jr., Gates Foundation's Influence Criticized, N.Y. Times, Feb 16, 2008

- ↑ "Artemisinin combination therapy for the treatment of childhood malaria in Sub-Saharan Africa: Efficacy, safety and policy considerations". Retrieved 25 November 2016.

- ↑ "Amazon Malaria Initiative". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Towards an African-driven malaria vaccine development program: history and activities of the African Malaria Network Trust (AMANET).". PMID 18165504.

- ↑ "Malaria Consortium 2003-2013: a decade in communicable disease control and child health". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Top-Ranked Charities". GiveWell. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ↑ "MalariaWorld". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "South Africa Launches Collaborative Malaria Initiative That Aims To Develop New Treatment, Prevention Methods". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "The role of vector control in stopping the transmission of malaria: threats and opportunities". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Malaria No More". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Nothing but Nets".

- ↑ "Taskforce on Innovative International Financing for Health Systems: showing the way forward". Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- ↑ "Imagine No Malaria". Retrieved 24 November 2016.

- ↑ "ALMA" (PDF). Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "MESA". Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Evimalar" (PDF). Retrieved 28 November 2016.

- ↑ "Dundee University".

- ↑ "Dundee drug obtained".

This article is issued from Wikipedia - version of the 12/1/2016. The text is available under the Creative Commons Attribution/Share Alike but additional terms may apply for the media files.