Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico

| Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico | |

|---|---|

| Unincorporated community | |

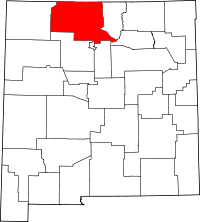

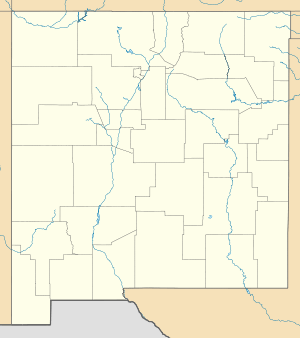

Tierra Amarilla Location within the state of New Mexico | |

| Coordinates: 36°42′01″N 106°32′59″W / 36.70028°N 106.54972°WCoordinates: 36°42′01″N 106°32′59″W / 36.70028°N 106.54972°W[1] | |

| Country | United States |

| State | New Mexico |

| County | Rio Arriba |

| Elevation[1] | 7,529 ft (2,295 m) |

| Time zone | MST (UTC-7) |

| • Summer (DST) | MDT (UTC-6) |

| ZIP code | 87575 |

| Area code | 505 |

| FIPS code | 35-77670 [1] |

| GNIS feature ID | 0923704 [1] |

Tierra Amarilla is a small unincorporated community near the Carson National Forest in the northern part of the U.S. state of New Mexico.[1] It is the county seat of Rio Arriba County.[2]

Tierra Amarilla is Spanish for "Yellow Soil". The name refers to clay deposits found in the Chama River Valley and used by Native American peoples.[3]:352–353[4] Tewa and Navajo toponyms for the area also refer to the yellow clay.[3]:352–353

History

There is evidence of 5000 years of habitation in the Chama River Valley including pueblo sites south of Abiquiu. The area served as a trade route for peoples in the present-day Four Corners region and the Rio Grande Valley. Navajos later used the valley as a staging area for raids on Spanish settlements along the Rio Grande. Written accounts of the Tierra Amarilla locality by pathfinding Spanish friars in 1776 described it as suitable for pastoral and agricultural use. The route taken by the friars from Santa Fe to California became the Spanish Trail. During the Californian Gold Rush the area became a staging point for westward fortune seekers.[5]

Tierra Amarilla Grant

The Tierra Amarilla Grant was created in 1832 by the Mexican government for Manuel Martinez and settlers from Abiquiu.[3]:352–353[4] The land grant encompassed a more general area than the contemporary community known as Tierra Amarilla.[3]:352–353 The grant holders were unable to maintain a permanent settlement due to "raids by Utes, Navajos and Jicarilla Apaches" until early in the 1860s.[4] In 1860 the United States Congress confirmed the land grant as a private grant, rather than a community grant, due to mistranslated and concealed documents.[6] Although a land patent for the grant required the completion of a geographical survey before issuance, some of Manuel Martinez' heirs began to sell the land to Anglo speculators. In 1880 Thomas Catron sold some of the grant to the Denver and Rio Grande Railway for the construction of their San Juan line and a service center at Chama. By 1883 Catron had consolidated the deeds he held for the whole of the grant sans the original villages and their associated fields. In 1950, the descendants of the original grant holder's court petitions to reclaim communal land were rebuked.[6]

Rio Arriba's county seat

In 1866 the United States Army established Camp Plummer just south of Los Ojos (established in 1860) to rein in already decreased Native American activity on the grant. The military encampment was deserted in 1869.[3]:57, 210, 352–353 Las Nutrias, the site of the contemporary community, was founded nearby c.1862. The first post office in Las Nutrias was established in 1866 and bore the name Tierra Amarilla, as did the present one which was established in 1870 after an approximately two-year absence.[3]:352–353 In 1877 a U.S. Army lieutenant described the village as "the center of the Mexican population of northwestern New Mexico".[4] The territorial legislature located Rio Arriba's county seat in Las Nutrias and renamed the village in 1880.[3]:352–353 The Denver and Rio Grande Railway's 1881 arrival at Chama,[7] about ten miles to the north, had profound effects on the development of the region by bringing the area out of economic and cultural isolation.[6]

When Tierra Amarilla was designated as the county seat the villagers set about building a courthouse.[4] This structure was demolished to make way for the present one, which was built in 1917 and gained notoriety fifty years later when it was the location of a gunfight between land rights activists and authorities.[8] The neoclassical design by Isaac Rapp is now on the National Register of Historic Places.[9]

Courthouse raid

The Alianza Federal de Mercedes, led by Reies Tijerina, raided the Rio Arriba County Courthouse in 1967. Attempting to make a citizen's arrest of the district attorney "to bring attention to the unscrupulous means by which government and Anglo settlers had usurped Hispanic land grant properties", an armed struggle in the courthouse ensued resulting in Tijerina and his group fleeing to the south with two prisoners as hostages. Eulogio Salazar, a prison guard, was shot and Daniel Rivera, a sheriff's deputy, was badly injured. The National Guard, FBI and New Mexico State Police successfully pursued Tijerina, who was sentenced to less than three years.[4]

Geography

The Brazos Cliffs are a prominent nearby landmark and attraction. Also nearby are the artificial Heron Lake and El Vado Lake. Tierra Amarillas' Elevation is 7,524 feet above sea level.

Layout

The settlement is situated in a cluster of villages along United States Route 84 and the Chama River.[4] The layout of the villages, including the one that became Tierra Amarilla, do not follow the urban planning principles of the Laws of the Indies.[5]

Demographics

Tierra Amarilla has the ZIP code of 87575. The ZIP Code Tabulation Area for ZIP Code 87575 had a population of 750 at the 2000 census.[10]

Notable people

- Walter K. Martinez, New Mexico lawyer and state legislator, was born in Tierra Amarilla.[11]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Geographic Names Information System (GNIS) details for Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico; United States Geological Survey (USGS); November 13, 1980.

- ↑ "Find a County". National Association of Counties. Retrieved 2011-06-07.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Julyan, Robert Hickson (1998). The Place Names of New Mexico (Revised/2nd ed.). Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. ISBN 0-8263-1689-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pike, David (2004). Roadside New Mexico: a guide to historic markers. Albuquerque: University of New Mexico Press. pp. 81–82. ISBN 978-0-8263-3118-2. OCLC 53967286. ISBN 0-8263-3118-1. Retrieved 4 August 09. Check date values in:

|access-date=(help) - 1 2 Southwest Crossroads Spotlight (2006). "Tierra Amarilla". SAR Press, School for Advanced Research. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- 1 2 3 Wilson, Chris; David Kammer (1989). "La Tierra Amarilla: Its History, Architecture and Cultural Landscape". Santa Fe: Museum of New Mexico Press. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ Myrick, David F. (1970). New Mexico's Railroads: An Historical Survey. Golden: Colorado Railroad Museum. p. 104.

- ↑ Whisenhunt, Donald W. (1979). New Mexico Courthouses (annotated ed.). El Paso: Texas Western Press, University of Texas at El Paso. p. 31.

- ↑ "State Listings". National Register of Historic Places. Retrieved 2009-10-29.

- ↑ "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- ↑ University of New Mexico Law School-Distinguished Honorees-Walter K. Martinez