Accessory nerve

| Accessory nerve | |

|---|---|

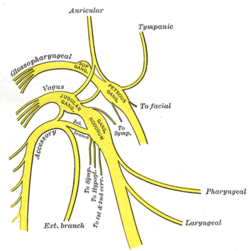

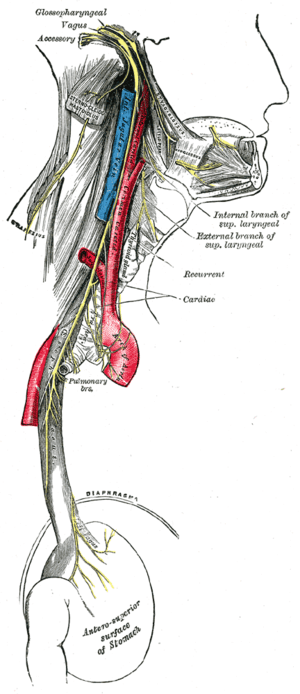

Diagram of the upper portions of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves. | |

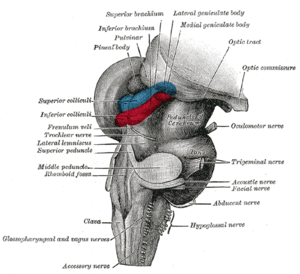

Inferior view of the human brain, with the cranial nerves labelled. | |

| Details | |

| Innervates | sternocleidomastoid muscle, trapezius muscle |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus accessorius |

| MeSH | A08.800.800.120.060 |

| TA | A14.2.01.184 |

| FMA | 6720 |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

The accessory nerve is a cranial nerve that controls the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles. As part of it was formerly believed to originate in the brain, it is considered the eleventh of twelve cranial nerves, or simply cranial nerve XI.

Traditional descriptions of the accessory nerve divide it into two parts: a spinal part and a cranial part.[1] However, because the cranial component rapidly joins the vagus nerve, becoming an integral part of said nerve, modern descriptions often consider the cranial component to be part of the vagus nerve and not part of the accessory nerve proper.[2] For this reason, in contemporary discussions of the accessory nerve, the common practice is to dismiss the cranial part altogether, referring to the accessory nerve specifically as the spinal accessory nerve.

The spinal accessory nerve provides motor innervation from the central nervous system to two muscles of the neck: the sternocleidomastoid muscle and the trapezius muscle. The sternocleidomastoid muscle tilts and rotates the head, while the trapezius muscle has several actions on the scapula, including shoulder elevation and abduction of the arm.

Range of motion and strength testing of the neck and shoulders can be measured during a neurological examination to assess function of the spinal accessory nerve. Limited range of motion or poor muscle strength are suggestive of damage to the spinal accessory nerve, which can result from a variety of causes. Injury to the spinal accessory nerve is most commonly caused by medical procedures that involve the head and neck.[3] Clinically, iatrogenic injury usually results in severe wasting and loss of volume of the trapeizus muscle which is, typically, very noticeable.

The accessory nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic spinal segments C1–C6.

Structure

Unlike all other cranial nerves, the spinal accessory nerve begins outside the skull rather than inside. In particular, in the majority of individuals, the fibers of the spinal accessory nerve originate solely in neurons situated in the upper spinal cord, from where the spinal cord begins at the junction with the medula, to the level of about C6.[4][5] These fibers coalesce to form spinal rootlets, roots, and finally the spinal accessory nerve itself, which enters the skull through the foramen magnum, the large opening at the base of the skull.[4] The nerve courses along the inner wall of the skull towards the jugular foramen,[4] through which it exits the skull with the glossopharyngeal and vagus nerves.[6] Owing to its peculiar course, the spinal accessory nerve is notable for being the only cranial nerve to both enter and exit the skull.

Once the cranial component has detached from the spinal component, the spinal accessory nerve continues alone and heads posteriorly (backwards) and inferiorly (downwards) upon exiting the skull through the jugular foramen. In the neck, the accessory nerve crosses the internal jugular vein around the level of the posterior belly of digastric muscle. Masoud Saman et al. in a study of 84 necks[7] reported that in the anterior triangle of the neck the accessory nerve crossed the internal jugular vein anteriorly in 80% of necks, posteriorly in 19% and in the one case of internal jugular vein bifurcation, the nerve pierced the vein. The average distance traveled by nerve from base of skull to crossing the internal jugular vein was 2.38 cm. As it courses downwards, the nerve pierces the sternocleidomastoid muscle while sending it motor branches, then continues inferiorly until it reaches the trapezius muscle to provide motor innervation to its upper portion.[8]

Traditionally, the accessory nerve is described as having a small cranial component that descends from the medulla and briefly connects with the spinal accessory component before branching off of the nerve to join the vagus nerve.[4] A study, published in 2007, of twelve subjects suggests that in the majority of individuals, this cranial component does not make any distinct connection to the spinal component; the roots of these distinct components were separated by a fibrous sheath in all but one subject.[5]

Nucleus

The fibers that form the spinal accessory nerve are formed by lower motor neurons located in the upper segments of the spinal cord. This cluster of neurons, called the spinal accessory nucleus, is located in the lateral aspect of the anterior horn of the spinal cord, and stretches from where the spinal cord begins (at the junction with the medulla) through to the level of about C6.[4] This is in contrast to most other motor neurons, whose cell bodies are found in the spinal cord's anterior horn. The lateral horn of high cervical segments appears to be continuous with the nucleus ambiguus of the medulla oblongata, from which the cranial component of the accessory nerve is derived.

Function

The accessory nerve provides motor control of the sternocleidomastoid and trapezius muscles.[6] The trapezius muscle controls the action of shrugging the shoulders, and the sternocleidomastoid the action of turning the head.[6] Like most muscles, control of the trapezius muscle arises from the opposite side of the brain.[6] Contraction of the muscle raises the scapula. The nerve fibres sternocleidomastoid however are thought to change sides (Latin: decussate) twice. This means the sternocleidomastoid is controlled by the brain on the same side of the body. Contraction of the stenocleidomastoid fibres turns the head to the opposite side, the net effect meaning that the head is turned to the side of the brain receiving visual information from that area.[6]

Clinical significance

Injury

Injury to the spinal accessory nerve can occur above the accessory nerve nucleus, as the nerve passes into the skull, or in the neck.[8] Injury can cause an accessory nerve disorder, which results in diminished or absent function of the sternocleidomastoid muscle and upper portion of the trapezius muscle.

The distal part of the spinal accessory nerve is most susceptible to injury. Throughout much of its course, the nerve is protected from injury by the muscles it innervates. It is in the interval between protection from these muscles, which corresponds to the distal part of the nerve, that the spinal accessory nerve is most vulnerable to injury. Such injury may be caused by trauma or as a result of surgery. Injury to this part of the nerve will result in weakness of the trapezius muscle on the side of the damage, leading to a traction injury of the brachial plexus.[8]

Examination

The accessory nerve is tested by evaluating the function of the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles.[6] The trapezius muscle is tested by asking the patient to shrug their shoulders with and without resistance. The sternocleidomastoid muscle is tested by asking the patient to turn their head to the left or right against resistance.[6]

One-sided weakness of the trapezius may indicate injury to the nerve on the same side of an injury to the spinal accessory nerve on the same side (Latin: ipsilateral) of the body being assessed.[6] Weakness in head-turning suggests injury to the contralateral spinal accessory nerve: a weak leftward turn is indicative of a weak right sternocleidomastoid muscle (and thus right spinal accessory nerve injury), while a weak rightward turn is indicative of a weak left sternocleidomastoid muscle (and thus left spinal accessory nerve).[6]

Hence, weakness of shrug on one side and head-turning on the other side may indicate damage to the accessory nerve on the side of the shrug weakness, or damage along the nerve pathway at the other side of the brain. Causes of damage may include trauma or past surgery, tumours, and causes of compression at the jugular foramen.[6] Weakness in both muscles may point to a more general disease process such as motor neuron disease, Guillain-Barre syndrome or poliomyleitis.[6]

Surgery

The spinal accessory nerve is removed as part of a radical neck dissection which is performed for control of neck lymph node metastasis.[8]

History

In 1848, Jones Quain described the nerve as the "spinal nerve accessory to the vagus", recognizing that while a minor component of the nerve joins with the larger vagus nerve, the majority of accessory nerve fibers originate in the spinal cord.[9] Quain also suggested spinal accessory nerve as a shortened form of the term; this term, and its more abbreviated variant, accessory nerve, have persisted to modern times. Throughout this interval, the nerve has never had a consistent name among investigators and medical practitioners. Some use accessory nerve and spinal accessory nerve interchangeably; others distinguish between spinal accessory nerve and cranial accessory nerve; still others use accessory nerve to refer to both spinal and cranial components of the nerve.

In Neuroanatomy and the Neurologic Exam, Terence R. Anthoney provides a historical account of the usage of the terms accessory nerve, spinal accessory nerve, and cranial accessory nerve, summarized in the following excerpt:

To summarize, then, the eleventh cranial nerve was called both the "accessory nerve" and the "spinal accessory nerve" as early as 1848—"accessory" referring to its fibers which became accessory to the vagus nerve and "spinal" referring to its largely spinal origin. When it became recognized, as early as 1893, that the "accessory" fibers to the vagus nerve came from the same medullary nuclei as the rest of the vagal efferent fibers, people began to view the "accessory" fibers as part of the vagus nerve proper, leaving the eleventh cranial nerve to originate solely from its spinal nucleus. This shift was reinforced by the neuroclinicians, who could only test the integrity of the spinal portion of the nerve separately anyway. Because of the shift to just a spinal origin for the nerve, the word "accessory" came to be associated with the "true"—i.e., spinal—component of the nerve, no longer being considered in the context of "accessory to the vagus." This association has been reinforced by referring to the spinal nucleus of origin as the "(spinal) accessory nucleus."[10]

Classification

Among investigators there is disagreement regarding the terminology used to describe the type of information carried by the accessory nerve. As the trapezius and sternocleidomastoid muscles are derived from the branchial arches, some investigators believe the spinal accessory nerve that innervates them must carry branchiomeric (special visceral efferent, SVE) information.[11] This is in line with the observation that the spinal accessory nucleus appears to be continuous with the nucleus ambiguus of the medulla. Others, notably Haines, consider the spinal accessory nerve to carry general somatic efferent (GSE) information.[12] Still others believe it is reasonable to conclude that the spinal accessory nerve contains both SVE and GSE components.[13]

Additional images

-

Dura mater and its processes exposed by removing part of the right half of the skull, and the brain.

-

Hind- and mid-brains; postero-lateral view.

-

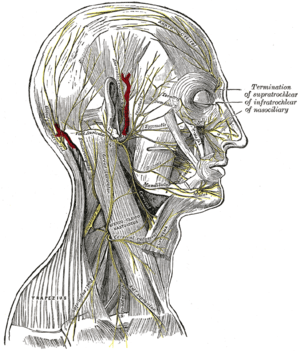

The nerves of the scalp, face, and side of neck.

-

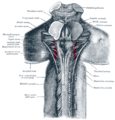

Upper part of medulla spinalis and hind- and mid-brains; posterior aspect, exposed in situ.

-

Course and distribution of the glossopharyngeal, vagus, and accessory nerves.

-

Plan of the cervical plexus.

-

Side of neck, showing chief surface markings.

-

Spinal cord. Brachial plexus. Cerebrum, inferior view, deep dissection.

References

- ↑ "The Accessory Nerve". Gray's Anatomy of the Human Body.

- ↑ "Spinal Accessory Nerve". Structure of the Human body, Loyola University Medical Education Network. Archived from the original on 16 June 2007. Retrieved 2007-06-17.

- ↑ London J, London NJ, Kay SP (1996). "Iatrogenic accessory nerve injury". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 78 (2): 146–50. PMC 2502542

. PMID 8678450.

. PMID 8678450. - 1 2 3 4 5 Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 459.

- 1 2 Ryan S, Blyth P, Duggan N, Wild M, Al-Ali S (2007). "Is the cranial accessory nerve really a portion of the accessory nerve? Anatomy of the cranial nerves in the jugular foramen". Anatomical Science International. 82 (1): 1–7. doi:10.1111/j.1447-073X.2006.00154.x. PMID 17370444.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 Talley, Nicholas (2014). Clinical Examination. Churchill Livingstone. pp. 424–5. ISBN 9780729541985.

- ↑ Saman M, Etebari P, Pakdaman MN, Urken ML (2010). "Anatomic relationship between the spinal accessory nerve and the jugular vein: a cadaveric study". Surgical and Radiologic Anatomy. 33 (2): 175–179. doi:10.1007/s00276-010-0737-y. PMID 20959982.

- 1 2 3 4 Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 460.

- ↑ Jones Quain (1848). Richard Quain; William Sharpey, eds. Elements of Anatomy. 2 (5th ed.). London: Taylor, Walton, and Maberly. p. 812.

- ↑ Terence R. Anthoney (1993). Neuroanatomy and the Neurologic Exam: A Thesaurus of Synonyms, Similar-Sounding Non-Synonyms, and Terms of Variable Meanings. Boca Raton: CRC-Press. pp. 69–73. ISBN 0-8493-8631-4.

- ↑ William T. Mosenthal (1995). A Textbook of Neuroanatomy: With Atlas and Dissection Guide. Washington, DC: Taylor & Francis. p. 12. ISBN 1-85070-587-9.

- ↑ Duane E. Haines (2004). Neuroanatomy: an atlas of structures, sections, and systems. Hagerstown, MD: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 0-7817-4677-9.

- ↑ Joshi SS, Joshi SD (2001). "Muscle Dorso-Fascialis — A Case Report". Journal of the Anatomical Society of India. 50 (2): 159–160.

- Books

- editor-in-chief, Susan Standring ; section editors, Neil R. Borley; et al. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Nervus accessorius. |

- MedEd at Loyola GrossAnatomy/h_n/cn/cn1/cn11.htm

- lesson6 at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University)

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (XI)

- Anatomy photo:28:13-0115 at the SUNY Downstate Medical Center

- Cranial Nerves at Yale 11-1