Hypoglossal nerve

| Hypoglossal nerve | |

|---|---|

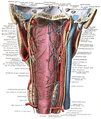

Hypoglossal nerve, cervical plexus, and their branches. | |

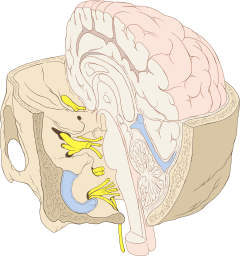

The hypoglossal nerve arises as a series of rootlets, from the caudal brain stem, here seen from below. | |

| Details | |

| To | ansa cervicalis |

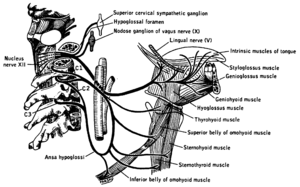

| Innervates | genioglossus, hyoglossus, styloglossus, geniohyoid, thyrohyoid, intrinsic muscles of the tongue |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | nervus hypoglossus |

| MeSH | A08.800.800.120.330 |

| TA | A14.2.01.191 |

| FMA | 50871 |

| Cranial nerves |

|---|

|

The hypoglossal nerve is the twelfth cranial nerve, and innervates all the extrinsic and intrinsic muscles of the tongue, except for the palatoglossus.[lower-alpha 1] It is solely a motor nerve. The nerve arises from the hypoglossal nucleus in the brain stem as a number of small rootlets, passes through the hypoglossal canal and down through the neck, and eventually passes up again over the tongue muscles it supplies into the tongue. There is a nerve on the left and the right side of the body

The nerve is involved in controlling tongue movements required for speech and swallowing. Lesions or damage to the nerve or the neural pathways which control it can affect the ability of the tongue to move and its appearance.

The name hypoglossus springs from the fact that its passage is below the tongue, hypo meaning "under", and glossus meaning "tongue", both of which are from Ancient Greek.

Structure

The hypoglossal nerve arises from the hypoglossal nucleus near the bottom of the brain stem. It begins as a number of smaller rootlets emerging from the front of the medulla[1][2] in the preolivary sulcus, which separates the olive and the pyramid.[3] The nerve passes through the subarachnoid space and exits the skull and its base through the hypoglossal canal.[2]

After emerging from the hypoglossal canal, it gives off a small meningeal branch and picks up a branch from the anterior ramus of C1. It then travels close to the vagus nerve and spinal division of the accessory nerve,[2] spirals behind the vagus nerve and passes between the internal carotid artery and internal jugular vein lying on the carotid sheath.[4] After passing deep to the posterior belly of the digastric muscle,[4] it passes to the submandibular region, passes upwards and anteriorly on the hyoglossus muscle, and deep to the stylohyoid muscle and lingual nerve.[5] It then passes up on the outer side of the genioglossus muscle and continues in a forward direction to the tip of the tongue. It distributes branches to the intrinsic and extrinsic muscle of the tongue innervates as it passes in this direction.[6]

Signals from muscle spindles on the tongue travel through the hypoglossal nerve, moving onto the lingual nerve which synapses on the trigeminal mesencephalic nucleus.[2]

Innervation of the hypoglossal nucleus from the motor cortex is bilateral.[7]

The hypoglossal nerve leaves the skull through the hypoglossal canal, which is situated near the large opening for the spinal cord, the foramen magnum.

The hypoglossal nerve leaves the skull through the hypoglossal canal, which is situated near the large opening for the spinal cord, the foramen magnum. After leaving the skull, the hypoglossal nerve spirals around the vagus nerve and then passes behind the deep belly of the digastric muscle

After leaving the skull, the hypoglossal nerve spirals around the vagus nerve and then passes behind the deep belly of the digastric muscle

Development

The hypoglossal nerve is derived from the basal plate of the embryonic medulla oblongata.[8]

Function

The hypoglossal nerve provides motor control of the extrinsic muscles of the tongue: genioglossus, hyoglossus, styloglossus, and the intrinsic muscles of the tongue.[2] These represent all muscles of the tongue except the palatoglossus muscle.[2] The hypoglossal nerve is of a general somatic efferent (GSE) type.[2]

The nerve is involved in swallowing to clear themouth of saliva and other involuntary activities. The hypoglossal nucleus interacts with the reticular formation, involved in the control of several reflexive or automatic motions, and several corticonuclear originating fibers supply innervation aiding in unconscious movements relating to speech and articulation.[2]

Clinical significance

Damage

Damage or lesions to the nerve is classified according to the relation of the damage to the hypoglossal nucleus. Thus damage may be supranuclear (Latin: supra, lit. 'above'), nuclear or infranuclear (Latin: infra, lit. 'below'). Such injuries damage either an upper motor neuron (supranuclear) or the lower motor neuron (intranuclear) Damage can be on one or both sides, which will affect symptoms that the damage causes.[2]

An injury that is supranuclear will cause the tongue to deviate away from the injured side. Such injuries can give rise to crossed symptoms due to a majority of the supranuclear innervation to the hypoglossal nucleus being crossed. This deviation will only be seen in the initial days after the injury, after which when the tongue is protroded it won't deviate, even though the nerve does not recover function.[2] Supranuclear damage to both the left and right tracts often occurs in conjunction with damage to facial and trigeminal nerve dysfunction. This often occurs due to thrombotic damage to the brainstem following arteriosclerosis of the vertebrobasilar artery. Such a stroke may result in tight oral musculature, and difficulty speaking, eating and chewing.[2]

Infranuclear lesions will lead to paralysis of the hypoglossal nerve leading to atrophy of muscles of the tongue.[2] Infranuclear injuries will cause deviation of the tongue towards the affected side when it is stuck out. This is because of the weaker genioglossal muscle.[2]

Progressive bulbar palsy, a neuromuscular atrophy associated with combined lesions of the hypoglossal nucleus and nucleus ambiguus upon atrophy of motor nerves of the pons and medulla. The symptoms are those of dysfunctional movements of the tongue leading to speech and chewing impairments, as well as swallowing difficulties, caused by dysfunction of several cranial nerve nuclei. Otherwise, the symptoms are similar to those of infranuclear lesions.[2]

Examination

The hypoglossal nerve is tested by sticking the tongue out. If there is damage to the nerve or its pathways, the tongue will involuntarily curve to one side, due to unopposed action of the opposite genioglossus muscle. If this is the result of a lower motor neuron lesion, the tongue will curve toward the damaged side, combined with the presence of fasciculations (twitches) or atrophy. However, if the deficit is caused by an upper motor neuron lesion, the tongue will curve away from the side of the cortical damage, without the presence of either fasciculations or wasting (atrophy).[10] Lower motor neuron damage can be to either the nerve or the nucleus. Unilateral atrophy of the muscle may be seen as a reduction in the size of the tongue on the affected side, but may also show as "wrinkling" of the tongue on the damaged side. Fasciculations may look similar to ordinary motion of the tongue, which may also be affected by tremor. For fasciculations to be indicative of neural damage they should also be present when the tongue is in a rested position, and are likened to making the tongue look like a "bag of worms".[7]

Deviation is not always present when the nerve is damaged, and tongue strength can be tested by asking a person to poke the inside of their cheek while feeling or administering counter-pressure on the outside of the cheek. Neither is it necessary to see pronounced weakness if the damage is in the upper motor neurons, when speech difficulties may be more evident.[7]

Weakness of the tongue is displayed as a slurring of speech. The tongue may feel "thick", "heavy", or "clumsy." Lingual sounds (i.e., l's, t's, d's, n's, r's, etc.) are slurred and this is obvious in conversation.[11] Damage may manifest differently, and testing of posterior and anterior function of the tongue may be done through assessing ability to make a "k" or "t" sound respectively.[7]

Use in nerve repair

The hypoglossal nerve may be connected ("anastamosed") to the facial nerve to attempt to restore function when the facial nerve is damaged. Facial nerve paralysis with localised injuries (due to for example, trauma or cancer) may attempt to be repaired by either wholly or partially selecting nerve fibres from the hypoglossal nerve and connecting them to the facial nerve.[12][13]

History

The first recorded description of the hypoglossal nerve was by Herophilos (335–280 BC), although it was not named at the time.The first use of the name hypoglossal in Latin as nervi hypoglossi externa was used by Winslow in 1733. This was followed though by several different namings including nervi indeterminati, par lingual, par gustatorium, great sub-lingual by different authors, and gustatory nerve and lingual nerve (by Winslow). It was listed in 1778 as nerve hypoglossum magnum by Soemmering. It was then named as the great hypoglossal nerve by Cuvier in 1800 as a translation of Winslow and finally named in English by Knox in 1832.[14]

Other animals

Development of the nerve in rodents and reptiles may give some clues as to evolutionary origins and organization of the hypoglossal nerve. Nerves supplying lingual muscles, geniohyoid and infrahyoid (or hypobranchial muscle sheet) of common embryonic origin in reptiles arise from a sustained branch of neurons reaching between the caudal medulla and level with the third cervical spinal nerves outlet. This is relevant because caudal portions of the hypoglossal nucleus are intertwined with certain motor neurons of the cervical spinal cord through the supraspinal nucleus which additionally supplies the thyrohyoid through the first spinal nerve. An organization which may be present among humans, but has not been proven occurs in rodents where the first cervical nerve has also been shown to include fibres originating from the caudal hypoglossal nucleus which pass on to innervate certain intrinsic muscles of the tongue after joining with the hypoglossal nerve somewhere along the neck.[2]

See also

Additional Images

The hypoglossal nerve is labeled at left.

The hypoglossal nerve is labeled at left. The hypoglossal nerve is visible at the bottom on its way and passing though the hypoglossal canal.

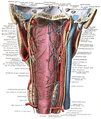

The hypoglossal nerve is visible at the bottom on its way and passing though the hypoglossal canal.- Hypoglossal nerve, dissection

- Hypoglossal nerve, dissection

- Hypoglossal nerve, dissection

- Hypoglossal nerve, dissection

References

- ↑ Dale Purves (2012). Neuroscience. Sinauer Associates. p. 726. ISBN 978-0-87893-695-3.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 M. J. T. Fitzgerald; Gregory Gruener; Estomih Mtui (2012). Clinical Neuroanatomy and Neuroscience. Saunders/Elsevier. p. 216. ISBN 978-0-7020-4042-9.

- ↑ Anthony H. Barnett (2006). Diabetes: Best Practice & Research Compendium. Elsevier Health Sciences. p. 30. ISBN 0-323-04401-8.

- 1 2 Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 460.

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 506.

- ↑ Gray's Anatomy 2008, p. 506–507.

- 1 2 3 4 Kandel, Eric R. (2013). Principles of neural science (5. ed.). Appleton and Lange: McGraw Hill. pp. 1541–1542. ISBN 978-0-07-139011-8.

- ↑ "Neural - Cranial Nerve Development". embryology.med.unsw.edu.au. Retrieved 17 June 2016.

- ↑ Mukherjee, Sudipta; Gowshami, Chandra; Salam, Abdus; Kuddus, Ruhul; Farazi, Mohshin; Baksh, Jahid (2014-01-01). "A case with unilateral hypoglossal nerve injury in branchial cyst surgery". Journal of Brachial Plexus and Peripheral Nerve Injury. 07 (01). doi:10.1186/1749-7221-7-2. PMC 3395866

. PMID 22296879.

. PMID 22296879. - ↑

- ↑ "Chapter 7: Lower cranial nerves". www.dartmouth.edu. Retrieved 2016-05-12.

- ↑ Yetiser, Sertac; Karapinar, Ugur (2007-07-01). "Hypoglossal-Facial Nerve Anastomosis: A Meta-Analytic Study". Annals of Otology, Rhinology & Laryngology. 116 (7): 542–549. doi:10.1177/000348940711600710. ISSN 0003-4894.

- ↑ Ho, Tang. "Facial Nerve Repair Treatment". WebMDLLC. Retrieved 9 December 2011.

- ↑ Neuroanatomical Terminology: A Lexicon of Classical Origins and Historical Foundations. p. 300. ISBN 978-0-19-534062-4.

- Sources

- Susan Standring; Neil R. Borley; et al., eds. (2008). Gray's anatomy : the anatomical basis of clinical practice (40th ed.). London: Churchill Livingstone. ISBN 978-0-8089-2371-8.

Notes

- ↑ These are the genioglossus, hyoglossus, styloglossus, and intrinsic muscles of the tongue.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hypoglossal nerve. |

- hier-701 at NeuroNames

- MedEd at Loyola GrossAnatomy/h_n/cn/cn1/cn12.htm

- cranialnerves at The Anatomy Lesson by Wesley Norman (Georgetown University) (XII)

- Notes on Hypoglossal nerve