Muni Metro

| |||

|

| |||

| Overview | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Owner | San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency | ||

| Locale | San Francisco, California | ||

| Transit type | Light rail/Streetcar | ||

| Number of lines |

6 (plus 1 peak-hour shuttle line) | ||

| Number of stations |

33 (9 subway, 24 surface)[1] 87 additional surface stops | ||

| Daily ridership | 128,500 (average weekday, Q4 2014)[2] | ||

| Annual ridership | 56.7 million (2014)[2] | ||

| Website | SFMTA | ||

| Operation | |||

| Began operation | February 18, 1980 | ||

| Operator(s) | San Francisco Municipal Railway | ||

| Number of vehicles |

151 Breda light rail vehicles (high floor)[3] | ||

| Train length | 75-150 feet (1-2 LRVs)[4] | ||

| Technical | |||

| System length | 36.8 mi (59.2 km)[5] | ||

| Track gauge |

4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm) (standard gauge)[4] | ||

| Electrification | Overhead lines, 600 V DC[4] | ||

| Average speed | 9.6 mph (15.4 km/h)[6] | ||

| Top speed | 35 mph (56 km/h)[7] | ||

| |||

Muni Metro is a light rail/streetcar hybrid system serving San Francisco, California, operated by the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni), a division of the San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency (SFMTA). With an average weekday ridership of 128,500 passengers as of the fourth quarter of 2014, Muni Metro is the United States' third busiest light rail system.[2] Muni Metro operates a fleet of 151 light rail vehicles (LRV) made by Breda.[3]

Muni Metro is the modern incarnation of the traditional streetcar system that had served San Francisco since the late 19th century. While many streetcar lines in other cities, and even in San Francisco itself, were converted to buses after World War II, five lines survived until 1980, when the streetcar lines were partially upgraded to light rail with the opening of the upper level of the Market Street Subway in that year; full daily Muni Metro service was inaugurated in 1982. Recently, the system has undergone expansion, most notably the Third Street Light Rail Project, completed in 2007, which started the first new rail line in San Francisco in over half a century. Other projects, such as the Central Subway, are underway.

History

Beginnings

Muni Metro descended from the municipally-owned traditional streetcar system started on December 28, 1912, when the San Francisco Municipal Railway (Muni) was established.[8] The first streetcar line, the A Geary, ran from Kearny and Market Streets in the Financial District to Fulton Street and 10th Avenue in the Richmond District.[9] The system slowly expanded, opening the Twin Peaks Tunnel in 1917,[10] allowing streetcars to run to the southwestern quadrant of the city. The last line to start service before 2007 was the N Judah, which started service after the Sunset Tunnel opened in 1928.[11]

In the 1940s and 1950s, as in many North American cities, public transit in San Francisco was consolidated under the aegis of a single municipal corporation, which then began phasing out much of the streetcar network in favor of buses.[12] However, five heavily used streetcar lines traveled for at least part of their routes through tunnels or otherwise reserved right-of-way, and thus could not be converted to bus lines.[13] As a result, these lines, running PCC streetcars, continued in operation.

Original plans for the BART system drawn up in the 1950s envisioned a double-decker subway tunnel under Market Street (known as the Market Street Subway) in downtown San Francisco; the lower deck would be dedicated to express trains, while the upper would be served by local trains whose routes would spread south and west through the city. After construction of the tunnel had begun, however, these plans were altered; only a single BART route would travel through the city on the lower deck, while the upper deck would be served by the existing Muni streetcar routes. The new tunnel would be connected to the existing Twin Peaks Tunnel. The new underground stations would feature high platforms, and the older stations would be retrofitted with the same, which meant that the PCCs could not be used in them. Hence, a fleet of new light rail vehicles was ordered from Boeing-Vertol, but were not delivered until 1979–80, even though the tunnel was completed in 1978. The K and M lines were extended to Balboa Park during this time, providing further connections to BART. (The J line also saw an extension there in 1991, which provided yet another BART connection at Glen Park.)

On February 18, 1980, the Muni Metro was officially inaugurated, with weekday N line service in the subway.[14] The Metro service was implemented in phases, and the subway was served only on weekdays until 1982. The K Ingleside line began using the Metro subway on weekdays on June 11, 1980, the L Taraval and M Ocean View lines on December 17, 1980, and lastly the J Church line on June 17, 1981.[15] Meanwhile, weekend service on all five lines (J, K, L, M, N) continued to use PCC cars operating on the surface of Market Street through to the Transbay Terminal, and the Muni Metro was closed on weekends. At the end of the service day September 19, 1982, streetcar operations on the surface of Market Street were discontinued entirely, the remaining PCC cars taken out of service, and weekend service on the five light rail lines was temporarily converted to buses.[16][17] Finally, on November 20, 1982, the Muni Metro subway began operating seven days a week.[17]

At the time, there were no firm plans to revive any service on the surface of Market Street or return PCCs to regular running.[16] However, tracks were rehabilitated for the 1983 Historic Trolley Festival[17] and the inauguration of the F Line, served by heritage streetcars, soon followed.

Muni meltdown

In the mid- to late-1990s, San Francisco grew more prosperous and its population expanded with the advent of the dot-com boom, and the Metro system began to feel the strain of increased commuter demand. Muni criticism had been something of a feature of life in San Francisco, and not without reason. The Boeing trains were sub-par and grew crowded quickly. And the difficulty in running a hybrid streetcar and light rail system, with five lines merging into one, led to scheduling problems on the main trunk lines with long waits between arrivals and commuter-packed trains sometimes sitting motionless in tunnels for extended periods of time.

Muni did take steps to address these problems. Newer, larger Breda cars were ordered, an extension of the system towards South Beach — where many of the new dot-coms were headquartered — was built, and the underground section was switched to Automatic Train Operation (ATO), making it the only light rail line in the world to be so operated. The Breda cars, however, came in noisy, overweight, oversized, under-braked, and over-budget (their price grew from US$2.2 million per car to nearly US$3 million over the course of their production).[18][19] In fact, the new trains were so heavy (10,000 pounds (4,500 kg) more than the Boeing LRVs they replaced) that some homeowners, claiming that the exceptional weight of the Breda cars damaged their foundations, sued the city of San Francisco.[20] The Breda cars are longer and wider than the previous Boeing cars, necessitating the modification of subway stations and maintenance yards, as well as the rear view mirrors on the trains themselves.[19] Furthermore, the Breda cars do not run in three car trains, like the Boeing cars used to, as doing so had, in some instances, physically damaged the overhead power wires.[21] The Breda trains were so noisy that San Francisco budgeted over $15 million to quiet them down, while estimates range up to $1 million per car to remedy the excessive noise.[22] To this day, the Breda cars are noisier than the PCC or Boeing cars. In 1998, NTSB inspectors mandated a lower speed limit of 30 mph (48 km/h), down from 50 mph (80 km/h), because the brakes were problematic.[23][24]

The ATC system was plagued by numerous glitches when first implemented, initially causing significantly more harm than good. Common occurrences included sending trains down the wrong tracks, and, more often, inappropriately applying emergency braking.[25] Eventually the result was a spectacular service crisis, widely referred to as the "Muni meltdown", in the summer of 1998. During this period, two reporters for the San Francisco Chronicle—one riding in the Muni Metro tunnel and one on foot on the surface—held a race through downtown, with the walking reporter emerging the winner.[26]

After initial problems with the ATC were fixed, substantial upgrades to the entire Muni transit systems have gone a long way towards resolving persistent crowding and scheduling issues. Nonetheless, Muni remains one of the slowest urban transport systems in the United States.

Recent expansion

In 1980, the M Ocean View was extended from Broad Street and Plymouth Avenue to its current terminus at Balboa Park.[5] In 1991, the J Church was extended from Church and 30th Streets to its current terminus at Balboa Park.[5] In 1998, the N Judah was extended from Embarcadero Station to the planned site of the new AT&T Park (then called Pacific Bell Park) and Caltrain Depot,[27] after that extension was briefly served between January and August of that year by the temporary E Embarcadero[28][29] light rail shuttle (restored in 2015 as the E Embarcadero heritage streetcar line).

In 2007, the T Third Street, running south from Caltrain Depot along Third Street to the southern edge of the city, opened as part of the Third Street Light Rail Project. Limited weekend T line service began on January 13, 2007, while full service began on April 7, 2007. The line initially ran from the southern terminus at Bayshore Boulevard and Sunnydale Street to Castro Street Station in the north. The line ran into initial problems with breakdowns, bottlenecks, and power failures, creating massive delays.[30] Service changes to address complaints with the introduction of the T Third Street were implemented on June 30, 2007, when the K and T trains were interlined, or effectively merged into one single line with route designations changing at the entrances into the subway (T becomes K outbound at Embarcadero; K becomes T inbound at West Portal).[31]

Future expansion

Several expansion projects are underway or under study. Federal funding has been secured for, and construction has begun on, the Central Subway,[32] a combined surface and subway extension of the T Third Line, running from Caltrain Depot to Chinatown, with stops at Moscone Center and Union Square, and with the potential for a future expansion to North Beach and Fisherman's Wharf.[33] Muni estimates that the Central Subway section of the T Third Line will carry roughly 35,100 riders per day by 2030.[34] The Central Subway is projected to be complete and ready for revenue service by 2019,[35] at a projected cost of $1.578 billion.[34] The Central Subway extension is seen as a precondition for future light rail transit along the heavily used Geary corridor, because the Central Subway will provide much of the downtown, subterranean infrastructure that a light rail system along Geary would require. Once the Central Subway is complete, it may also continue as an above-ground light rail line through North Beach, and into the Marina district, with the possibility of eventually terminating in the Presidio.

Infrastructure

The Muni Metro system consists of 71.5 miles (115.1 km) of standard gauge track, seven light rail lines (six regular lines and one peak-hour line), three tunnels, nine subway stations, twenty-four surface stations, and eighty-seven surface stops.[36]

The backbone of the system is formed by two interconnected subway tunnels, the older Twin Peaks Tunnel and the newer Market Street Subway, both controlled by automatic train operation systems to run trains with the operators closing the door to allow the train to pull out of a station. This ATO system was upgraded in 2015 to replace outdated software and relays.[37] The tunnels, 5.5 miles (8.9 km) in total length,[5] run from West Portal Station in the southwestern part of the city to Embarcadero Station in the heart of the Financial District. Three lines, the K Ingleside, the L Taraval, and the M Ocean View feed into the tunnel at West Portal, while two lines, the J Church and N Judah, enter at a portal near Church Street and Duboce Avenue in the Duboce Triangle neighborhood. Two lines, the N Judah and T Third Street, enter and exit the tunnel at Embarcadero. An additional tunnel, the Sunset Tunnel, is located near the Duboce portal and is served by the N.

The interconnected tunnels contain nine subway stations.[1] Three stations, West Portal, Forest Hill and the now-defunct Eureka Station were opened in 1918 as part of the Twin Peaks Tunnel,[38] while the other seven, Castro Street, Church Street, Van Ness, Civic Center, Powell Street, Montgomery Street and Embarcadero were opened in 1980 as part of the Market Street Subway. Four stations, Civic Center, Powell Street, Montgomery Street, and Embarcadero, are shared with Bay Area Rapid Transit (BART), with Muni Metro on the upper level and BART on the lower one.[39]

Above ground, there are twenty-four surface platform stations.[1] Two stations, Stonestown and San Francisco State University are located at the southwestern part of the city, while the rest are located on the eastern side of the city, where the system underwent recent expansion as part of the Embarcadero extension and the Third Street Light Rail Project. However, many of the stops on the system are surface stops consisting of anything from a traffic island to a yellow-banded "Car Stop" sign painted on a utility pole.[40]

All subway and surface stations are handicap-accessible. In addition, several surface street stops are also handicap-accessible, often consisting of a ramp leading up to a small platform for boarding.[41]

In Muni Metro terminology, an inbound train is one that heads from the western neighborhoods and West Portal towards Embarcadero, while an outbound train travels in the opposite direction out of downtown towards the west. Even the T Third Street Line is consistent with this terminology, with an inbound train going from West Portal through Embarcadero to Sunnydale, and an outbound train running out of the southeastern neighborhoods into downtown.[42]

Muni Metro has two rail yards for storage and maintenance:

- Green Yard or Curtis E. Green Light Rail Center at 425 Geneva Avenue is located adjacent to Balboa Park Station and serves as the outbound terminus for the J Church, K Ingleside, and M Ocean View. The facility has repair facilities, an outdoor storage yard and larger carhouse structure. The facility was renamed for former and late head of Muni in 1987.[43]

- Muni Metro East is a newer facility opened in 2008 and is located along the Central Waterfront on Illinois and 25th Streets in the Potrero Hill neighborhood, a block from the T Third Street line.[44] The 180,000 square foot maintenance facility with outdoor storage area is located next to Northern Container Terminal and former Army Pier.

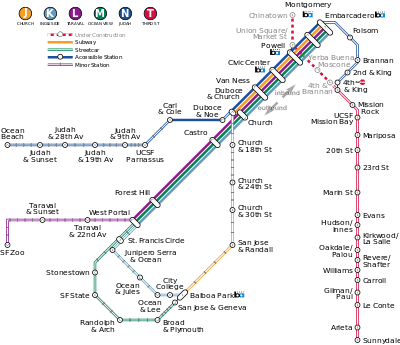

Routes

| Line | Year opened[5][45] |

Termini | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| | J Church | 1917 | Embarcadero Station | Balboa Park Station |

| | K Ingleside | 1918 | Embarcadero Station | Balboa Park Station |

| | L Taraval | 1919 | Embarcadero Station | 46th Avenue and Wawona San Francisco Zoo |

| | M Ocean View | 1925 | Embarcadero Station | San Jose and Geneva Balboa Park Station |

| | N Judah | 1928 | 4th and King Station Caltrain Depot | Judah and La Playa Ocean Beach |

| | T Third Street | 2007 | West Portal Station | Sunnydale Station |

| | S Castro Shuttle (peak hours & game days) | 1995 | Embarcadero Station 4th and King Station (game days) | Castro Station West Portal Station (game days) |

Fleet

Muni Metro first operated Boeing Vertol-made US Standard Light Rail Vehicles (USSLRV), which were built for Muni Metro and Boston's MBTA.[46] Boeing had no experience in making LRVs,[46] and has not made another since.[47] Acquired due to the federal government offering to provide much of the funding,[47] the cars were prone to jammed doors, leaky roofs, mechanical breakdowns, and several accidents. In fact, 30 vehicles on Muni Metro's fleet were ones that the MBTA rejected after suffering numerous breakdowns.[47] Despite its shortcomings, the cars constituted the entire light rail fleet until 1996, when new Breda-manufactured cars were put into service.[48] After suffering initial breakdowns[49] and despite facing complaints of noise and vibrations,[50] the Bredas gradually replaced the Boeings, with the last Boeing car being retired in 2002.[47]

There are 151 LRVs on the fleet, all made by Breda.[3] The double-ended cars are 75 feet (23 m) long, 9 feet (2.7 m) wide, 11 feet (3.4 m) high, have graffiti-resistant windows, and contain an air-conditioning system to maintain a temperature of 72 °F (22 °C) inside the car.[51] With the construction of the Central Subway and ongoing system capacity increase, there are plans to acquire an additional 24 cars with Siemens, Kawasaki, and CAF having been prequalified to bid. The contract was awarded to Siemens for the purchase of a total of 260 cars (the first 24 to go to operate on the Central Subway), and Muni is expected to choose from three initial designs in the new S200 class. They are expected to have the same coupling device as the Breda cars, however, the new Siemens trains can couple up to four cars at a time.[3][52] On July 2, 2015, Muni was awarded a grant of $41 million from the California Transportation Agency to eventually pay for 40 of the 64 additional Siemens light rail vehicles.[53]

Fares and operations

Muni Metro runs from approximately 5 am to 1 am weekdays, with later start times of 7 am on Saturday and 8 am on Sunday.[54] Owl service, or late-night service, is provided along much of the L and N lines by buses that bear the same route designation.[54]

The basic fare for Muni Metro, like Muni buses, is $2.25 for adults and $1.00 for youth ages 5–17, seniors, and the disabled.[55] Like Muni buses, the Muni Metro operates on a proof-of-payment system;[56] on paying a fare, the passenger will receive a ticket good for travel on any bus, historic streetcar, or Metro vehicle for 90 minutes.[55] Payment methods depend on boarding location. On surface street sections in the south and west of the city, passengers can board at the front of the train and pay their fare to the train operator to receive their ticket; those who already have a ticket, or who have a daily, weekly, or monthly pass, can board at any door of the Metro streetcar.[56] Subway stations have controlled entries via faregates, and passengers usually purchase or show Muni staff a ticket in order to enter the platform area. Faregates closest to an unmanned Muni staff booth open automatically if a passenger has a valid pass or transfer that cannot be scanned.[56] Muni's fare inspectors may board trains at any time to check for proof of payment from passengers.[56]

All cars are also equipped with Clipper card readers near each entrance, which riders may use to tag their cards to pay their fare. The cards themselves are then used as proof of payment; fare inspectors carry handheld card readers that can verify that payment was made. In subway stations, riders instead tag their cards on the faregates to gain access to the platforms.

See also

|

References

- 1 2 3 "San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency Capital Investment Plan — FY 2009-2013" (PDF). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. August 15, 2008. Retrieved January 22, 2009.

- 1 2 3 "Transit Ridership Report Fourth Quarter and End-of-Year 2014" (pdf). American Public Transportation Association (APTA) (via: http://www.apta.com/resources/statistics/Pages/RidershipArchives.aspx ). March 3, 2015. Retrieved April 5, 2015. External link in

|publisher=(help) - 1 2 3 4 "2010 SFMTA Transit Fleet Management Plan" (pdf). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- 1 2 3 "San Francisco LRV Specifications" (pdf). Ansaldobreda. Retrieved March 3, 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Demery, Jr., Leroy W. (November 2011). "U.S. Urban Rail Transit Lines Opened From 1980" (pdf). publictransit.us. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- ↑ "San Francisco Muni: Unique Cost/Operating Environment" (pdf). San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. July 26, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ Reisman, Will (December 14, 2010). "Muni Metro trackway trouble unresolved". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved January 21, 2011.

- ↑ "A Brief History of the F-Market & Wharves Line". Market Street Railway. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Streetcars: The A Line". Western Neighborhoods Project. May 22, 2002. Retrieved March 8, 2008.

- ↑ Wallace, Kevin (March 27, 1949). "The City's Tunnels: When S.F. Can't Go Over, It Goes Under Its Hills". San Francisco Chronicle. SFGenealogy. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- ↑ "N Judah Streetcar Line". Western Neighborhoods Project. October 18, 2007. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Muni's History". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved November 3, 2013.

- ↑ "This Is Light Rail Transit" (pdf). Light Rail Transit Committee. Transportation Research Board. November 2000. p. 7. Retrieved August 6, 2014.

- ↑ Perles, Anthony (1981). The People's Railway: The History of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Glendale, CA (US): Interurban Press. p. 250. ISBN 0-916374-42-4.

- ↑ McKane, John; Perles, Anthony (1982). Inside Muni: The Properties and Operations of the Municipal Railway of San Francisco. Glendale, CA (US): Interurban Press. pp. 189–202. ISBN 0-916374-49-1.

- 1 2 Soiffer, Bill (September 20, 1982). "The Last Streetcar On Top of Market". San Francisco Chronicle, p. 2.

- 1 2 3 Perles, Anthony (1984). Tours of Discovery: A San Francisco Muni Album. Interurban Press. pp. 126, 136. ISBN 0-916374-60-2.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward (April 22, 1999). "Muni Investing in More Breda Streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- 1 2 McCormick, Erin (April 21, 1997). "Muni rolling out first of new fleet of streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ "J-Line Residents Ready to Rumble Over Breda Cars". The Noe Valley Voice. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Coupling without orders is technically an avoidable accident". Rescue MUNI. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward (August 14, 1997). "Muni Plans to Quiet Streetcars". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Fundamental Flaws Derail Hopes of Improving Muni". San Francisco Chronicle. June 23, 1997. Retrieved April 18, 2007.

- ↑ "Real-time Subways". Gin and Tonic. 2004. Retrieved April 21, 2007.

- ↑ "EBs in the Subway--ARRGH". Rescue Muni. 1998. Archived from the original on February 8, 2012. Retrieved 2007-04-21.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward; Rubenstein, Steve (September 1, 1998). "A Walker Matches Train Pace". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward (August 26, 1998). "Brown Tries To Soothe Muni Riders / Service on N-Judah line has been abysmal all week - SFGate". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward (January 9, 1998). "Embarcadero Line On Track Tomorrow". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A-17. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ↑ Taylor, Michael (April 6, 1998). "PAGE ONE -- Muni's New E-Line No Beeline / Trains more tardy, irregular than buses - SFGate". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved March 27, 2013.

- ↑ Gordon, Rachel (April 12, 2007). "Passengers Left in Lurch By T-Third's Rough Start". San Francisco Chronicle. p. A-1. Retrieved March 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Service Changes Effective June 30, 2007". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. 2007. Retrieved July 2, 2007.

- ↑ "San Francisco's Central Subway Project Receives Outstanding Rating from FTA". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved 2009-08-03.

- ↑ Vega, Cecilia M. (February 20, 2008). "S.F. Chinatown subway plan gets agency's nod". San Francisco Chronicle. p. B-1. Retrieved March 13, 2009.

- 1 2 "FAQS MTA Central Subway". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ↑ "Central Subway - Project Overview". SFMTA. Retrieved August 18, 2013.

- ↑ "Muni Metro Light Rail". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved November 22, 2013.

- ↑ Rodriguez, Joe Fitzgerald (May 10, 2015). "Tech in the tunnels: Muni train control system gets biggest upgrade since the '90s". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved 26 May 2015.

- ↑ "West of Twin Peaks". Western Neighborhoods Project. May 9, 2006. Retrieved January 14, 2009.

- ↑ Bei, R. (1978). "San Francisco's Muni Metro, A Light-Rail Transit System". TRB Special Report No. 182, Light-Rail Transit: Planning and Technology. Transportation Research Board. Retrieved August 22, 2010.

- ↑ "Info for New Riders: How do I find a bus stop?". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved August 3, 2009.

- ↑ "Muni Metro accessibility". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ "Route Description for T Third Street". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved January 30, 2013.

- ↑ Nolte, Carl (June 24, 2011). "Curtis E. Green -- rose from bus driver to head of S.F. Muni". The San Francisco Chronicle.

- ↑ Gordon, Rachel (September 17, 2008). "S.F. streetcars get a new maintenance yard". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ Demery, Jr., Leroy W. (October 25, 2010). "U.S. Urban Rail Transit Lines Opened From 1980: Appendix". publictransit.us. Retrieved November 2, 2013.

- 1 2 Sullivan, Kathleen (September 14, 1998). "Muni knew about trolley lemons in '70s". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 Lelchuk, Ilene (January 14, 2002). "Muni cars on a roll into city junkyard". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved December 9, 2012.

- ↑ Nolte, Carl (December 10, 1996). "Stylish New Streetcars Ready to Roll". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward; Lynem, Julie N. (August 29, 1998). "Brown Descends To Take Hellish Journey on Muni". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ Epstein, Edward (July 9, 1997). "Streetcar Racket Figures in Contract". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

- ↑ Salter, Stephanie (January 26, 1997). "Beefy, but they whine". San Francisco Examiner. Retrieved February 15, 2009.

- ↑ Cabanatuan, Michael (July 16, 2014). "$1.2 billion contract OKd for new Muni Metro light-rail cars". San Francisco Chronicle. Hearst Communications, Inc. Retrieved July 17, 2014.

- ↑ Chinn, Jerold (2 July 2015). "Muni secures $41 million for new Metro trains". Retrieved 2 July 2015.

- 1 2 "Muni Metro Service". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved January 20, 2007.

- 1 2 "Fares and Sales". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. Retrieved July 3, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 "Proof of Payment". San Francisco Municipal Transportation Agency. February 4, 2008. Retrieved February 14, 2009.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Muni Metro. |