Clofazimine

| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Lamprene |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a682128 |

| ATC code | J04BA01 (WHO) |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Biological half-life | 70 days |

| Identifiers | |

| |

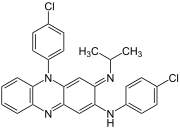

| Synonyms | N,5-bis(4-chlorophenyl)-3-(1-methylethylimino)-5H-phenazin-2-amine |

| CAS Number |

2030-63-9 |

| PubChem (CID) | 2794 |

| DrugBank |

DB00845 |

| ChemSpider |

21159573 |

| UNII |

D959AE5USF |

| KEGG |

D00278 |

| ChEMBL |

CHEMBL1292 |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.016.347 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

| Formula | C27H22Cl2N4 |

| Molar mass | 473.396 g/mol |

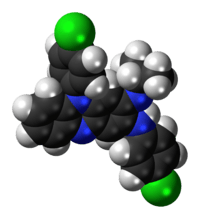

| 3D model (Jmol) | Interactive image |

| |

| |

| | |

Clofazimine is a fat-soluble iminophenazine dye used in combination with rifampicin and dapsone as multidrug therapy (MDT) for the treatment of leprosy. It has been used investigationally in combination with other antimycobacterial drugs to treat Mycobacterium avium infections in AIDS patients and Mycobacterium avium paratuberculosis infection in Crohn's disease patients. Clofazimine also has a marked anti-inflammatory effect and is given to control the leprosy reaction, erythema nodosum leprosum (ENL). (From AMA Drug Evaluations Annual, 1993, p1619). The drug is given as an alternative to patients who can not tolerate the effects of dapsone for tuberculosis.[1]

It is on the World Health Organization's List of Essential Medicines, a list of the most important medication needed in a basic health system.[2]

Side effects

Clofazimine produces pink to brownish skin pigmentation in 75-100% of patients within a few weeks, as well as similar discoloration of most bodily fluids and secretions. These discolorations are reversible but may take months to years to disappear. There is evidence in medical literature that as a result of clofazimine administration, several patients have developed depression which in some cases resulted in suicide. It has been hypothesized that the depression was a result of this chronic skin discoloration.[3]

Cases of icthyosis and skin dryness are also reported in response to this drug (8%-28%), as well as rash and itchiness (1-5%).

40-50% of patients develop gastrointestinal intolerance. Rarely, patients have died from bowel obstructions and intestinal bleeding, or required abdominal surgery to correct the same problem.

Mechanism

Clofazimine works by binding to the guanine bases of bacterial DNA, thereby blocking the template function of the DNA and inhibiting bacterial proliferation.[4][5] It also increases activity of bacterial phospholipase A2, leading to release and accumulation of lysophospholipids,[4][5] which are toxic and inhibit bacterial proliferation.[6][7]

Clofazimine is also a FIASMA (functional inhibitor of acid sphingomyelinase).[8]

Supply

Clofazimine is marketed under the trade name Lamprene by Novartis. One of the world's only producers of the clofazimine molecule is Sangrose Laboratories, located in Mavelikara, India.

Metabolism

Clofazimine has a biological half life of about 70 days. Autopsies performed on those who have died while on clofazimine show crystal-like aggregates in the intestinal mucosa, liver, spleen, and lymph nodes.[9]

Immunosuppressive effects

The immunosuppressive effects of clofazimine were immediately noticed when applied in animal model. Macrophages were first reported to be inhibited due to the stabilization of lysosomal membrane by clofazimine.[10] Clofazimine also showed a dosage-dependent inhibition of neutrophil motility, lymphocyte transformation,[11] mitogen-induced PBMC proliferation[12] and complement-mediated solubilization of pre-formed immune complexes in vitro.[13] A mechanistic studying of clofazimine in human T cells revealed that this drug is a Kv1.3 (KCNA3) channel blocker.[14] This indicates that clofazimine will be potentially used for treatment of multiple sclerosis, rheumatoid arthritis and type 1 diabetes. Because the Kv1.3-high effector memory T cells (TEM) are actively involved in the development of these diseases,[15] and Kv1.3 activity is essential for stimulation and proliferation of TEM by regulating calcium influx in the T cells.[16] Several clinical trials were also conducted looking for its immunosuppressive activity even before it was approved for leprosy by FDA. It was first reported to be effective in treating chronic discoid lupus erythematosus with 17 out of 26 patients got remission.[17] But later another group found it was ineffective in treating diffuse, photosensitive, systemic lupus erythematosus.[18] Clofazimine also has been sporadically reported with some success in other autoimmune diseases such as psoriasis,[19] Miescher’s granulomatous cheilitis,[20] Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis.[21] A recent clinical study of clofazimine was done in post-bone marrow transplantation patients[22] with over 50% of them having skin involvement, flexion contractures or oral manifestations achieved complete or partial responses. 7 out of 22 patients were able to reduce other immunosuppressants such as cyclosporine A.

History

Clofazimine, initially known as B663, was first synthesised in 1954 by a team of scientists at Trinity College, Dublin: Frank Winder, J.G. Belton, Stanley McElhinney, M.L. Conalty, Seán O'Sullivan, and Dermot Twomey, led by Vincent Barry. Clofazimine was originally intended as an anti-tuberculosis drug but drug proved ineffective. In 1959, a researcher named Y. T. Chang identified its effectiveness against leprosy. After clinical trials in Nigeria and elsewhere during the 1960s, Swiss pharmaceutical company Novartis launched the product in 1969 under the brand name Lamprene.

Novartis was granted FDA approval of clofazimine in December 1986 as an orphan drug. The drug is currently no longer available in the United States.[23]

References

- ↑ Clinical Microbiology Made Ridiculously Simple

- ↑ "WHO Model List of EssentialMedicines" (PDF). World Health Organization. October 2013. Retrieved 22 April 2014.

- ↑ Brown, Stoudemire (1998). Psychiatric Side Effects of Prescription and Over-the-counter Medications: Recognition and Management. American Psychiatric Pub.

- 1 2 Arbiser JL, Moschella SL (Feb 1995). "Clofazimine: a review of its medical uses and mechanisms of action". J Am Acad Dermatol. 32 (2 Pt 1): 241–7. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(95)90134-5. PMID 7829710.

- 1 2 Morrison N. E.; Morley G. M. (1976). "The mode of action of clofazimine: DNA binding studies". Int. J. Lepr. 44: 133–135.

- ↑ Dennis, E. A. 1983. Phospholipases, p. 307-353. In P. D. Boyer (ed.), The enzymes, 3rd ed., vol. 16. Lipid enzymology. Academic Press, Inc., New York.

- ↑ Kagan V. E. (1989). "Tocopherol stabilizes membrane against phospholipase A, free fatty acids and lysophospholipids". Ann. N.Y. Acad. Sci. 570: 121–135. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1989.tb14913.x. PMID 2698101.

- ↑ Kornhuber J, Muehlbacher M, Trapp S, Pechmann S, Friedl A, Reichel M, Mühle C, Terfloth L, Groemer T, Spitzer G, Liedl K, Gulbins E, Tripal P (2011). "Identification of novel functional inhibitors of acid sphingomyelinase". PLOS ONE. 6 (8): e23852. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0023852. PMC 3166082

. PMID 21909365.

. PMID 21909365. - ↑ Baik, J.; Rosania, G. R. (2011-07-29). "Molecular Imaging of Intracellular Drug–Membrane Aggregate Formation". Molecular Pharmaceutics. 8 (5): 1742–1749. doi:10.1021/mp200101b. PMC 3185106

. PMID 21800872. Retrieved 2012-02-01.

. PMID 21800872. Retrieved 2012-02-01. - ↑ Conalty ML, Barry VC, Jina A (Apr 1971). "The antileprosy agent B.663 (Clofazimine) and the reticuloendothelial system.". Int J Lepr Other Mycobact Dis. 39 (2): 479–92. PMID 4948088.

- ↑ Gatner EM, Anderson R, van Remsburg CE, Imkamp FM (Jun 1982). "The in vitro and in vivo effects of clofazimine on the motility of neutrophils and transformation of lymphocytes from normal individuals.". Lepr Rev. 53 (2): 85–90. PMID 7098757.

- ↑ van Rensburg CE, Gatner EM, Imkamp FM, Anderson R (May 1982). "Effects of clofazimine alone or combined with dapsone on neutrophil and lymphocyte functions in normal individuals and patients with lepromatous leprosy.". Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 21 (5): 693–7. doi:10.1128/aac.21.5.693. PMC 181995

. PMID 7049077.

. PMID 7049077. - ↑ Kashyap A, Sehgal VN, Sahu A, Saha K (Feb 1992). "Anti-leprosy drugs inhibit the complement-mediated solubilization of pre-formed immune complexes in vitro.". Int J Immunopharmacol. 14 (2): 269–73. doi:10.1016/0192-0561(92)90039-N. PMID 1624226.

- ↑ Ren YR, Pan F, Parvez S, Fleig A, Chong CR, Xu J, Dang Y, Zhang J, Jiang H, Penner R, Liu JO. (Dec 2008). Alberola-Ila, Jose, ed. "Clofazimine inhibits human Kv1.3 potassium channel by perturbing calcium oscillation in T lymphocytes.". PLOS ONE. 3 (12): e4009. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0004009. PMC 2602975

. PMID 19104661.

. PMID 19104661. - ↑ Beeton C, Wulff H, Standifer NE, Azam P, Mullen KM, Pennington MW, Kolski-Andreaco A, Wei E, Grino A, Counts DR, Wang PH, LeeHealey CJ, S Andrews B, Sankaranarayanan A, Homerick D, Roeck WW, Tehranzadeh J, Stanhope KL, Zimin P, Havel PJ, Griffey S, Knaus HG, Nepom GT, Gutman GA, Calabresi PA, Chandy KG (Nov 2006). "Kv1.3 channels are a therapeutic target for T cell-mediated autoimmune diseases.". Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 103 (46): 17414–9. doi:10.1073/pnas.0605136103. PMC 1859943

. PMID 17088564.

. PMID 17088564. - ↑ Wulff H, Calabresi PA, Allie R, Yun S, Pennington M, Beeton C, Chandy KG. "The voltage-gated Kv1.3 K(+) channel in effector memory T cells as new target for MS.". J Clin Invest. 111 (11): 1703–13. doi:10.1172/jci200316921.

- ↑ Mackey JP, Barnes J (Jul 1974). "Clofazimine in the treatment of discoid lupus erythematosus.". Br J Dermatol. 91 (1): 93–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1974.tb06723.x. PMID 4851057.

- ↑ Jakes JT, Dubois EL, Quismorio FP Jr (Nov 1982). "Antileprosy drugs and lupus erythematosus.". Ann Intern Med. 97 (5): 788. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-97-5-788_2. PMID 7137755.

- ↑ Chuaprapaisilp T, Piamphongsant T (Sep 1978). "Treatment of pustular psoriasis with clofazimine.". Br J Dermatol. 99 (3): 303–5. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2133.1978.tb02001.x. PMID 708598.

- ↑ Podmore P, Burrows D (Mar 1986). "Clofazimine--an effective treatment for Melkersson-Rosenthal syndrome or Miescher's cheilitis.". Clin Exp Dermatol. 11 (2): 173–8. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2230.1986.tb00443.x. PMID 3720016.

- ↑ Kelleher D, O'Brien S, Weir DG (1982). "Preliminary trial of clofazimine in chronic inflammatory bowel disease". Gut. 23: A432–A463. doi:10.1136/gut.23.5.A432. PMC 1419688

.

. - ↑ Lee SJ, Wegner SA, McGarigle CJ, Bierer BE, Antin JH (Apr 1997). "Treatment of chronic graft-versus-host disease with clofazimine.". Blood. 89 (7): 2298–302. PMID 9116272.

- ↑ http://reference.medscape.com/drug/clofazimine-342661

External links

- Official FDA Drug Label

- RxList Clofazimine (most information taken from FDA)

- U.S. National Library of Medicine: Drug Information Portal - Clofazimine