Chromatin

Chromatin is a complex of macromolecules found in cells, consisting of DNA, protein, and RNA. The primary functions of chromatin are 1) to package DNA into a smaller volume to fit in the cell, 2) to reinforce the DNA macromolecule to allow mitosis, 3) to prevent DNA damage, and 4) to control gene expression and DNA replication. The primary protein components of chromatin are histones that compact the DNA. Chromatin is only found in eukaryotic cells (cells with defined nuclei). Prokaryotic cells have a different organization of their DNA (the prokaryotic chromosome equivalent is called genophore and is localized within the nucleoid region).

The structure of chromatin depends on several factors. The overall structure depends on the stage of the cell cycle. During interphase, the chromatin is structurally loose to allow access to RNA and DNA polymerases that transcribe and replicate the DNA. The local structure of chromatin during interphase depends on the genes present on the DNA. That DNA which codes genes that are actively transcribed ("turned on") is more loosely packaged and associated with RNA polymerases (referred to as euchromatin) while that DNA which codes inactive genes ("turned off") is more condensed and associated with structural proteins (heterochromatin).[1][2] Epigenetic chemical modification of the structural proteins in chromatin also alters the local chromatin structure, in particular chemical modifications of histone proteins by methylation and acetylation. As the cell prepares to divide, i.e. enters mitosis or meiosis, the chromatin packages more tightly to facilitate segregation of the chromosomes during anaphase. During this stage of the cell cycle this makes the individual chromosomes in many cells visible by optical microscope.

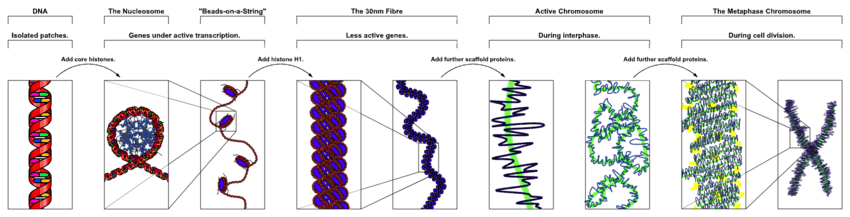

In general terms, there are three levels of chromatin organization:

- DNA wraps around histone proteins forming nucleosomes; the "beads on a string" structure (euchromatin).

- Multiple histones wrap into a 30 nm fibre consisting of nucleosome arrays in their most compact form (heterochromatin). (Definitively established to exist in vitro, the 30-nanometer fibre was not seen in recent X-ray studies of human mitotic chromosomes.[3])

- Higher-level DNA packaging of the 30 nm fibre into the metaphase chromosome (during mitosis and meiosis).

There are, however, many cells that do not follow this organisation. For example, spermatozoa and avian red blood cells have more tightly packed chromatin than most eukaryotic cells, and trypanosomatid protozoa do not condense their chromatin into visible chromosomes for mitosis.

Dynamic chromatin structure and hierarchy

Chromatin undergoes various structural changes during a cell cycle. Histone proteins are the basic packer and arranger of chromatin and can be modified by various post-translational modifications to alter chromatin packing (Histone modification). Most of the modifications occur on the histone tail. The consequences in terms of chromatin accessibility and compaction depend both on the amino-acid that is modified and the type of modification. For example, Histone acetylation results in loosening and increased accessibility of chromatin for replication and transcription. Lysine tri-methylation can either be correlated with transcriptional activity (tri-methylation of histone H3 Lysine 4) or transcriptional repression and chromatin compaction (tri-methylation of histone H3 Lysine 9 or 27). Several studies suggested that different modifications could occur simultaneously. For example, it was proposed that a bivalent structure (with tri-methylation of both Lysine 4 and 27 on histone H3) was involved in mammalian early development.[4]

Polycomb-group proteins play a role in regulating genes through modulation of chromatin structure.[5]

For additional information, see Histone modifications in chromatin regulation and RNA polymerase control by chromatin structure.

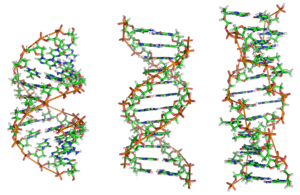

DNA structure

In nature, DNA can form three structures, A-, B-, and Z-DNA. A- and B-DNA are very similar, forming right-handed helices, whereas Z-DNA is a left-handed helix with a zig-zag phosphate backbone. Z-DNA is thought to play a specific role in chromatin structure and transcription because of the properties of the junction between B- and Z-DNA.

At the junction of B- and Z-DNA, one pair of bases is flipped out from normal bonding. These play a dual role of a site of recognition by many proteins and as a sink for torsional stress from RNA polymerase or nucleosome binding.

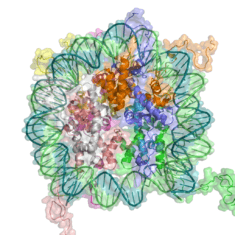

Nucleosomes and beads-on-a-string

- Main articles: Nucleosome, Chromatosome and Histone

The basic repeat element of chromatin is the nucleosome, interconnected by sections of linker DNA, a far shorter arrangement than pure DNA in solution.

In addition to the core histones, there is the linker histone, H1, which contacts the exit/entry of the DNA strand on the nucleosome. The nucleosome core particle, together with histone H1, is known as a chromatosome. Nucleosomes, with about 20 to 60 base pairs of linker DNA, can form, under non-physiological conditions, an approximately 10 nm "beads-on-a-string" fibre. (Fig. 1-2). .

The nucleosomes bind DNA non-specifically, as required by their function in general DNA packaging. There are, however, large DNA sequence preferences that govern nucleosome positioning. This is due primarily to the varying physical properties of different DNA sequences: For instance, adenine and thymine are more favorably compressed into the inner minor grooves. This means nucleosomes can bind preferentially at one position approximately every 10 base pairs (the helical repeat of DNA)- where the DNA is rotated to maximise the number of A and T bases that will lie in the inner minor groove. (See mechanical properties of DNA.)

30 nanometer chromatin fibre

Left: 1 start helix "solenoid" structure.

Right: 2 start loose helix structure.

Note: the histones are omitted in this diagram - only the DNA is shown.

With addition of H1, the beads-on-a-string structure in turn coils into a 30 nm diameter helical structure known as the 30 nm fibre or filament. The precise structure of the chromatin fibre in the cell is not known in detail, and there is still some debate over this.[6]

This level of chromatin structure is thought to be the form of heterochromatin, which contains mostly transcriptionally silent genes. EM studies have demonstrated that the 30 nm fibre is highly dynamic such that it unfolds into a 10 nm fiber ("beads-on-a-string") structure when transversed by an RNA polymerase engaged in transcription.

Linker DNA in yellow and nucleosomal DNA in pink.

The existing models commonly accept that the nucleosomes lie perpendicular to the axis of the fibre, with linker histones arranged internally. A stable 30 nm fibre relies on the regular positioning of nucleosomes along DNA. Linker DNA is relatively resistant to bending and rotation. This makes the length of linker DNA critical to the stability of the fibre, requiring nucleosomes to be separated by lengths that permit rotation and folding into the required orientation without excessive stress to the DNA. In this view, different lengths of the linker DNA should produce different folding topologies of the chromatin fiber. Recent theoretical work, based on electron-microscopy images[7] of reconstituted fibers supports this view.[8]

Spatial organization of chromatin in the cell nucleus

The spatial arrangement of the chromatin within the nucleus is not random - specific regions of the chromatin can be found in certain territories. Territories are, for example, the lamina-associated domains (LADs), and the topological association domains (TADs), which are bound together by protein complexes.[9] Currently, polymer models such as the Strings & Binders Switch (SBS) model[10] and the Dynamic Loop (DL) model[11] are used to describe the folding of chromatin within the nucleus.

Cell-cycle dependent structural organization

- Interphase: The structure of chromatin during interphase of mitosis is optimized to allow simple access of transcription and DNA repair factors to the DNA while compacting the DNA into the nucleus. The structure varies depending on the access required to the DNA. Genes that require regular access by RNA polymerase require the looser structure provided by euchromatin.

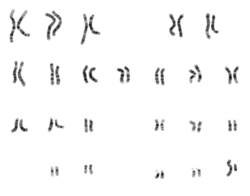

- Metaphase: The metaphase structure of chromatin differs vastly to that of interphase. It is optimised for physical strength and manageability, forming the classic chromosome structure seen in karyotypes. The structure of the condensed chromatin is thought to be loops of 30 nm fibre to a central scaffold of proteins. It is, however, not well-characterised.The physical strength of chromatin is vital for this stage of division to prevent shear damage to the DNA as the daughter chromosomes are separated. To maximise strength the composition of the chromatin changes as it approaches the centromere, primarily through alternative histone H1 analogues.It should also be noted that, during mitosis, while most of the chromatin is tightly compacted, there are small regions that are not as tightly compacted. These regions often correspond to promoter regions of genes that were active in that cell type prior to entry into chromatosis. The lack of compaction of these regions is called bookmarking, which is an epigenetic mechanism believed to be important for transmitting to daughter cells the "memory" of which genes were active prior to entry into mitosis.[12] This bookmarking mechanism is needed to help transmit this memory because transcription ceases during mitosis.

Chromatin and bursts of transcription

Chromatin and its interaction with enzymes has been researched, and a conclusion being made is that it is relevant and an important factor in gene expression. Vincent G. Allfrey, a professor at Rockefeller University, stated that RNA synthesis is related to histone acetylation.[13] The lysine amino acid attached to the end of the histones is positively charged. The acetylation of these tails would make the chromatin ends neutral, allowing for DNA access.

When the chromatin decondenses, the DNA is open to entry of molecular machinery. Fluctuations between open and closed chromatin may contribute to the discontinuity of transcription, or transcriptional bursting. Other factors are probably involved, such as the association and dissociation of transcription factor complexes with chromatin. The phenomenon, as opposed to simple probabilistic models of transcription, can account for the high variability in gene expression occurring between cells in isogenic populations[14]

Alternative chromatin organizations

During metazoan spermiogenesis, the spermatid's chromatin is remodeled into a more spaced-packaged, widened, almost crystal-like structure. This process is associated with the cessation of transcription and involves nuclear protein exchange. The histones are mostly displaced, and replaced by protamines (small, arginine-rich proteins).[15]

Methods to investigate chromatin

- ChIP-seq (Chromatin immunoprecipitation sequencing), aimed against different histone modifications, can be used to identify chromatin states throughout the genome. Different modifications have been linked to various states of chromatin.

- DNase-seq (DNase I hypersensitive sites Sequencing) uses the sensitivity of accessible regions in the genome to the DNase I enzyme to map open or accessible regions in the genome.

- FAIRE-seq (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements sequencing) uses the chemical properties of protein-bound DNA in a two-phase separation method to extract nucleosome depleted regions from the genome.[16]

- ATAC-seq (Assay for Transposable Accessible Chromatin sequencing) uses the Tn5 transposase to integrate (synthetic) transposons into accessible regions of the genome consequentially highlighting the localisation of nucleosomes and transcription factors across the genome.

- DNA footprinting is a method aimed at identifying protein-bound DNA. It uses labeling and fragmentation coupled to gel electrophoresis to identify areas of the genome that have been bound by proteins.[17]

- MNase-seq (Micrococcal Nuclease sequencing) uses the micrococcal nuclease enzyme to identify nucleosome positioning throughout the genome.[18][19]

- Chromosome conformation capture determines the spatial organization of chromatin in the nucleus, by inferring genomic locations that physically interact.

- MACC profiling (Micrococcal nuclease ACCessibility profiling) uses titration series of chromatin digests with micrococcal nuclease to identify chromatin accessibility as well as to map nucleosomes and non-histone DNA-binding proteins in both open and closed regions of the genome.[20]

Chromatin: alternative definitions

The term, introduced by Walther Flemming, has multiple meanings:

- Simple and concise definition: Chromatin is a macromolecular complex of a DNA macromolecule and protein macromolecules (and RNA). The proteins package and arrange the DNA and control its functions within the cell nucleus.

- A biochemists’ operational definition: Chromatin is the DNA/protein/RNA complex extracted from eukaryotic lysed interphase nuclei. Just which of the multitudinous substances present in a nucleus will constitute a part of the extracted material partly depends on the technique each researcher uses. Furthermore, the composition and properties of chromatin vary from one cell type to the another, during development of a specific cell type, and at different stages in the cell cycle.

- The DNA + histone = chromatin definition: The DNA double helix in the cell nucleus is packaged by special proteins termed histones. The formed protein/DNA complex is called chromatin. The basic structural unit of chromatin is the nucleosome.

Nobel Prizes

The following scientists were recognized for their contributions to chromatin research with Nobel Prizes:

| Year | Who | Award |

|---|---|---|

| 1910 | Albrecht Kossel (University of Heidelberg) | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discovery of the five nuclear bases: adenine, cytosine, guanine, thymine, and uracil. |

| 1933 | Thomas Hunt Morgan (California Institute of Technology) | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for his discoveries of the role played by the gene and chromosome in heredity, based on his studies of the white-eyed mutation in the fruit fly Drosophila.[21] |

| 1962 | Francis Crick, James Watson and Maurice Wilkins (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology, Harvard University and London University respectively) | Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their discoveries of the double helix structure of DNA and its significance for information transfer in living material. |

| 1982 | Aaron Klug (MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology) | Nobel Prize in Chemistry "for his development of crystallographic electron microscopy and his structural elucidation of biologically important nucleic acid-protein complexes" |

| 1993 | Richard J. Roberts and Phillip A. Sharp | Nobel Prize in Physiology "for their independent discoveries of split genes," in which DNA sections called exons express proteins, and are interrupted by DNA sections called introns, which do not express proteins. |

| 2006 | Roger Kornberg (Stanford University) | Nobel Prize in Chemistry for his discovery of the mechanism by which DNA is transcribed into messenger RNA. |

See also

- Chromatid

- Epigenetics

- Histone-Modifying Enzymes

- Position-effect variegation

- Salt-and-pepper chromatin

- Transcriptional bursting

- Active chromatin sequence

References

- ↑ "Chromatin Network Home Page.". Retrieved 2008-11-18.

- ↑ Dame, R.T. (May 2005). "The role of nucleoid-associated proteins in the organization and compaction of bacterial chromatin". Molecular Microbiology. 56 (4): 858–870. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2958.2005.04598.x. PMID 15853876.

- ↑ Hansen, Jeffrey (March 2012). "Human mitotic chromosome structure: what happened to the 30-nm fibre?". The EMBO Journal. 31 (7): 1621–1623. doi:10.1038/emboj.2012.66. PMC 3321215

. PMID 22415369.

. PMID 22415369. - ↑ Bernstein, B.E., T.S. Mikkelsen, X. Xie, M. Kamal, D.J. Huebert, J. Cuff, B. Fry, A. Meissner, M. Wernig, K. Plath, R. Jaenisch, A. Wagschal, R. Feil, S.L. Schreiber & E.S. Lander (April 2006). "A bivalent chromatin structure marks key developmental genes in embryonic stem cells". Cell. 125 (2): 315–26. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2006.02.041. ISSN 0092-8674. PMID 16630819.

- ↑ Portoso M, Cavalli G (2008). "The Role of RNAi and Noncoding RNAs in Polycomb Mediated Control of Gene Expression and Genomic Programming". RNA and the Regulation of Gene Expression: A Hidden Layer of Complexity. Caister Academic Press. ISBN 978-1-904455-25-7.

- ↑ Annunziato, Anthony T. "DNA Packaging: Nucleosomes and Chromatin". Scitable. Nature Education. Retrieved 2015-10-29.

- ↑ Robinson DJ; Fairall L; Huynh VA; Rhodes D. (April 2006). "EM measurements define the dimensions of the "30-nm" chromatin fiber: Evidence for a compact, interdigitated structure". PNAS. 103 (17): 6506–11. doi:10.1073/pnas.0601212103. PMC 1436021

. PMID 16617109.

. PMID 16617109.

- ↑ Wong H, Victor JM, Mozziconacci J. (September 2007). Chen, Pu, ed. "An All-Atom Model of the Chromatin Fiber Containing Linker Histones Reveals a Versatile Structure Tuned by the Nucleosomal Repeat Length". PLoS ONE. 2 (9): e877. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0000877. PMC 1963316

. PMID 17849006.

. PMID 17849006.

- ↑ Nicodemi M, Pombo A (June 2014). "Models of chromosome structure". Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 28: 90–5. doi:10.1016/j.ceb.2014.04.004. PMID 24804566.

- ↑ Nicodemi M, Panning B, Prisco A (May 2008). "A thermodynamic switch for chromosome colocalization". Genetics. 179 (1): 717–21. doi:10.1534/genetics.107.083154. PMC 2390650

. PMID 18493085.

. PMID 18493085. - ↑ Bohn M, Heermann DW (2010). "Diffusion-driven looping provides a consistent framework for chromatin organization". PLoS ONE. 5 (8): e12218. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0012218. PMC 2928267

. PMID 20811620.

. PMID 20811620.

- ↑ Xing H, Vanderford NL, Sarge KD (November 2008). "The TBP-PP2A mitotic complex bookmarks genes by preventing condensin action". Nat. Cell Biol. 10 (11): 1318–23. doi:10.1038/ncb1790. PMC 2577711

. PMID 18931662.

. PMID 18931662. - ↑ ALLFREY VG, FAULKNER R, MIRSKY AE (May 1964). "ACETYLATION AND METHYLATION OF HISTONES AND THEIR POSSIBLE ROLE IN THE REGULATION OF RNA SYNTHESIS". Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 51 (5): 786–94. doi:10.1073/pnas.51.5.786. PMC 300163

. PMID 14172992.

. PMID 14172992. - ↑ Kaochar S, Tu BP (November 2012). "Gatekeepers of chromatin: Small metabolites elicit big changes in gene expression". Trends Biochem. Sci. 37 (11): 477–83. doi:10.1016/j.tibs.2012.07.008. PMC 3482309

. PMID 22944281.

. PMID 22944281. - ↑ De Vries M, Ramos L, Housein Z, De Boer P (May 2012). "Chromatin remodelling initiation during human spermiogenesis". Biol Open. 1 (5): 446–57. doi:10.1242/bio.2012844. PMC 3507207

. PMID 23213436.

. PMID 23213436. - ↑ Giresi, Paul G.; Kim, Jonghwan; McDaniell, Ryan M.; Iyer, Vishwanath R.; Lieb, Jason D. (2007-06-01). "FAIRE (Formaldehyde-Assisted Isolation of Regulatory Elements) isolates active regulatory elements from human chromatin". Genome Research. 17 (6): 877–885. doi:10.1101/gr.5533506. ISSN 1088-9051. PMC 1891346

. PMID 17179217.

. PMID 17179217. - ↑ Galas, D. J.; Schmitz, A. (1978-09-01). "DNAse footprinting: a simple method for the detection of protein-DNA binding specificity". Nucleic Acids Research. 5 (9): 3157–3170. doi:10.1093/nar/5.9.3157. ISSN 0305-1048. PMC 342238

. PMID 212715.

. PMID 212715. - ↑ Cui, Kairong; Zhao, Keji (2012-01-01). "Genome-wide approaches to determining nucleosome occupancy in metazoans using MNase-Seq". Methods in Molecular Biology (Clifton, N.J.). 833: 413–419. doi:10.1007/978-1-61779-477-3_24. ISSN 1940-6029. PMC 3541821

. PMID 22183607.

. PMID 22183607. - ↑ Buenrostro, Jason D.; Giresi, Paul G.; Zaba, Lisa C.; Chang, Howard Y.; Greenleaf, William J. (2013-12-01). "Transposition of native chromatin for fast and sensitive epigenomic profiling of open chromatin, DNA-binding proteins and nucleosome position". Nature Methods. 10 (12): 1213–1218. doi:10.1038/nmeth.2688. ISSN 1548-7105. PMC 3959825

. PMID 24097267.

. PMID 24097267. - ↑ Mieczkowski J, Cook A, Bowman SK, Mueller B, Alver BH, Kundu S, Deaton AM, Urban JA, Larschan E, Park PJ, Kingston RE, Tolstorukov MY (2016-05-06). "MNase titration reveals differences between nucleosome occupancy and chromatin accessibility.". Nature Communications. 7: 11485. doi:10.1038/ncomms11485. PMC 4859066

. PMID 27151365.

. PMID 27151365. - ↑ "Thomas Hunt Morgan and His Legacy". Nobelprize.org. 7 Sep 2012

Other references

- Cooper, Geoffrey M. 2000. The Cell, 2nd edition, A Molecular Approach. Chapter 4.2 Chromosomes and Chromatin.

- Corces, V. G. (1995). "Chromatin insulators. Keeping enhancers under control". Nature. 376 (6540): 462–463. doi:10.1038/376462a0.

- Cremer, T. 1985. Von der Zellenlehre zur Chromosomentheorie: Naturwissenschaftliche Erkenntnis und Theorienwechsel in der frühen Zell- und Vererbungsforschung, Veröffentlichungen aus der Forschungsstelle für Theoretische Pathologie der Heidelberger Akademie der Wissenschaften. Springer-Vlg., Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Elgin, S. C. R. (ed.). 1995. Chromatin Structure and Gene Expression, vol. 9. IRL Press, Oxford, New York, Tokyo.

- Gerasimova, T. I.; Corces, V. G. (1996). "Boundary and insulator elements in chromosomes". Current Op. Genet. and Dev. 6: 185–192. doi:10.1016/s0959-437x(96)80049-9.

- Gerasimova, T. I.; Corces, V. G. (1998). "Polycomb and Trithorax group proteins mediate the function of a chromatin insulator". Cell. 92: 511–521. doi:10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80944-7.

- Gerasimova, T. I.; Corces, V. G. (2001). "CHROMATIN INSULATORS AND BOUNDARIES: Effects on Transcription and Nuclear Organization". Annu Rev Genet. 35: 193–208.

- Gerasimova, T. I.; Byrd, K.; Corces, V. G. (2000). "A chromatin insulator determines the nuclear localization of DNA [In Process Citation]". Mol Cell. 6: 1025–35. doi:10.1016/s1097-2765(00)00101-5.

- Ha, S. C.; Lowenhaupt, K.; Rich, A.; Kim, Y. G.; Kim, K. K. (2005). "Crystal structure of a junction between B-DNA and Z-DNA reveals two extruded bases". Nature. 437: 1183–6. doi:10.1038/nature04088. PMID 16237447.

- Pollard, T., and W. Earnshaw. 2002. Cell Biology. Saunders.

- Saumweber, H. 1987. Arrangement of Chromosomes in Interphase Cell Nuclei, p. 223-234. In W. Hennig (ed.), Structure and Function of Eucaryotic Chromosomes, vol. 14. Springer-Verlag, Berlin, Heidelberg.

- Sinden, R. R. (2005). "Molecular biology: DNA twists and flips". Nature. 437: 1097–8. doi:10.1038/4371097a.

- Van Holde KE. 1989. Chromatin. New York: Springer-Verlag. ISBN 0-387-96694-3.

- Van Holde, K., J. Zlatanova, G. Arents, and E. Moudrianakis. 1995. Elements of chromatin structure: histones, nucleosomes, and fibres, p. 1-26. In S. C. R. Elgin (ed.), Chromatin structure and gene expression. IRL Press at Oxford University Press, Oxford.

External links

- Chromatin, Histones & Cathepsin; PMAP The Proteolysis Map-animation

- [ Recent chromatin publications and news]

- Protocol for in vitro Chromatin Assembly

- ENCODE threads Explorer Chromatin patterns at transcription factor binding sites. Nature (journal)