Cheyletiella

| Cheyletiella | |

|---|---|

| |

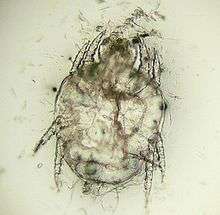

| Cheyletiella yasguri (?) from a dog | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Arachnida |

| Subclass: | Acari |

| Order: | Trombidiformes |

| Family: | Cheyletidae |

| Genus: | Cheyletiella G. Canestrini, 1886 |

| Type species | |

| Cheyletus parasitivorax Mégnin, 1878 | |

| Diversity | |

| 5 species (?) | |

| Synonyms | |

|

Ewingella | |

Cheyletiella is a genus of mites that live on the skin surface of dogs,[1] cats,[2] rabbits,[3] and humans.[4]

The adult mites are about 0.385 millimeters long, have eight legs with combs instead of claws, and have palpi that end in prominent hooks.[5] They do not burrow into the skin, but live in the keratin level. Their entire 21-day life cycle is on one host. They cannot survive off the host for more than 10 days.[6]

Cheyletiellosis

Cheyletiellosis (also known as Cheyletiella dermatitis),"[7] is a mild dermatitis caused by mites of the genus Cheyletiella. It is also known as walking dandruff due to skin scales being carried by the mites.

Cheyletiellosis is seen more commonly in areas where fleas are less prevalent, because of the decreased use of flea products that are also efficacious for the treatment of this mite.

Cheyletiellosis is highly contagious. Transmission is by direct contact with an affected animal.

Presentation

Symptoms in animals vary from no signs to intense itching, scales on the skin, and hair loss. The lesions are usually on the back of the animal. Symptoms in humans include multiple red, itchy bumps on the arms, trunk, and buttocks. Because humans are an irregular host for the mite, the symptoms usually go away in about three weeks. However, in some humans the mite infestation may be prolonged. It is believed that about 1% of the world population may be effected by these and other mites. The medical community does not accept the diagnosis of mite infestation in humans, but will treat the symptoms. A study is under way to determine what causes some humans to become host to mites. At this time it is believed that individuals with the following may be effected: compromised immune system, fungal or candida infections in the body, and parasites in the system.

Diagnosis

Diagnosis is by finding the mites or eggs microscopically in a skin scraping, combing, or on acetate tape applied to the skin.

Treatment

The most common treatment in animals is weekly use of some form of topical pesticide appropriate for the affected animal, often an antiflea product. Fipronil works well, especially in cats.[8]

In unresponsive cases, ivermectin is used.[6] Selamectin is also recommended for treatment.[9] None of these products are approved for treatment of cheyletiellosis.[10] Other pets in the same household should also be treated, and the house or kennel must be treated with an environmental flea spray.[11]

Species

- Cheyletiella blakei Smiley, 1970 — infests cats (Felis catus), USA (Washington DC)

- Cheyletiella parasitivorax — infests rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus),[6] France

- Cheyletiella romerolagi (Fain, 1972) — infests Romerolagus diazi, USA (New York)

- Cheyletiella strandtmanni Smiley, 1970 — infests hares (Lepus spp.), Taiwan

- Cheyletiella yasguri Smiley, 1965 — infests dogs

C. yasguri and C. blakei can transiently affect humans.[5]

See also

References

- ↑ Paradis M, Villeneuve A (August 1988). "Efficacy of Ivermectin against Cheyletiella yasguri Infestation in Dogs". Can. Vet. J. 29 (8): 633–635. PMC 1680781

. PMID 17423097.

. PMID 17423097. - ↑ Scott DW, Paradis M (December 1990). "A survey of canine and feline skin disorders seen in a university practice: Small Animal Clinic, University of Montréal, Saint-Hyacinthe, Québec (1987-1988)". Can. Vet. J. 31 (12): 830–835. PMC 1480900

. PMID 17423707.

. PMID 17423707. - ↑ Mellgren M, Bergvall K (2008). "Treatment of rabbit cheyletiellosis with selamectin or ivermectin: a retrospective case study". Acta Vet. Scand. 50: 1. doi:10.1186/1751-0147-50-1. PMC 2235873

. PMID 18171479.

. PMID 18171479. - ↑ Keh B, Lane RS, Shachter SP (February 1987). "Cheyletiella blakei, an ectoparasite of cats, as cause of cryptic arthropod infestations affecting humans". West. J. Med. 146 (2): 192–4. PMC 1307237

. PMID 3825118.

. PMID 3825118. - 1 2 Mueller, Ralf S. (2005). "Superficial mites in small animal dermatology" (PDF). Proceedings of the 50° Congresso Nazionale Multisala SCIVAC. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- 1 2 3 Griffin, Craig E.; Miller, William H.; Scott, Danny W. (2001). Small Animal Dermatology (6th ed.). W.B. Saunders Company. ISBN 0-7216-7618-9.

- ↑ Freedberg, et al. (2003). Fitzpatrick's Dermatology in General Medicine. (6th ed.). McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-138076-0.

- ↑ Scarampella F, Pollmeier M, Visser M, Boeckh A, Jeannin P (2005). "Efficacy of fipronil in the treatment of feline cheyletiellosis". Vet Parasitol. 129 (3-4): 333–9. doi:10.1016/j.vetpar.2005.02.008. PMID 15845289.

- ↑ Ihrke, Peter J. (2006). "New Approaches to Common Canine Ectoparasites" (PDF). Proceedings of the 31st World Congress of the World Small Animal Veterinary Association. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ↑ "Mange in Dogs and Cats". The Merck Veterinary Manual. 2006. Retrieved 2007-02-25.

- ↑ Jeromin, Alice (August 2006). "Cheyletiella: The under-diagnosed mite". DVM. Advanstar Communications: 8S–9S.

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Cheyletiella. |