Ceramic engineering

Ceramic engineering is the science and technology of creating objects from inorganic, non-metallic materials. This is done either by the action of heat, or at lower temperatures using precipitation reactions from high-purity chemical solutions. The term includes the purification of raw materials, the study and production of the chemical compounds concerned, their formation into components and the study of their structure, composition and properties.

Ceramic materials may have a crystalline or partly crystalline structure, with long-range order on atomic scale. Glass ceramics may have an amorphous or glassy structure, with limited or short-range atomic order. They are either formed from a molten mass that solidifies on cooling, formed and matured by the action of heat, or chemically synthesized at low temperatures using, for example, hydrothermal or sol-gel synthesis.

The special character of ceramic materials gives rise to many applications in materials engineering, electrical engineering, chemical engineering and mechanical engineering. As ceramics are heat resistant, they can be used for many tasks for which materials like metal and polymers are unsuitable. Ceramic materials are used in a wide range of industries, including mining, aerospace, medicine, refinery, food and chemical industries, packaging science, electronics, industrial and transmission electricity, and guided lightwave transmission.[1]

History

The word "ceramic" is derived from the Greek word κεραμικός (keramikos) meaning pottery. It is related to the older Indo-European language root "to burn", [2] "Ceramic" may be used as a noun in the singular to refer to a ceramic material or the product of ceramic manufacture, or as an adjective. The plural "ceramics" may be used to refer the making of things out of ceramic materials. Ceramic engineering, like many sciences, evolved from a different discipline by today's standards. Materials science engineering is grouped with ceramics engineering to this day.

Abraham Darby first used coke in 1709 in Shropshire, England, to improve the yield of a smelting process. Coke is now widely used to produce carbide ceramics. Potter Josiah Wedgwood opened the first modern ceramics factory in Stoke-on-Trent, England, in 1759. Austrian chemist Carl Josef Bayer, working for the textile industry in Russia, developed a process to separate alumina from bauxite ore in 1888. The Bayer process is still used to purify alumina for the ceramic and aluminium industries. Brothers Pierre and Jacques Curie discovered piezoelectricity in Rochelle salt circa 1880. Piezoelectricity is one of the key properties of electroceramics.

E.G. Acheson heated a mixture of coke and clay in 1893, and invented carborundum, or synthetic silicon carbide. Henri Moissan also synthesized SiC and tungsten carbide in his electric arc furnace in Paris about the same time as Acheson. Karl Schröter used liquid-phase sintering to bond or "cement" Moissan's tungsten carbide particles with cobalt in 1923 in Germany. Cemented (metal-bonded) carbide edges greatly increase the durability of hardened steel cutting tools. W.H. Nernst developed cubic-stabilized zirconia in the 1920s in Berlin. This material is used as an oxygen sensor in exhaust systems. The main limitation on the use of ceramics in engineering is brittleness. [1]

Military

The military requirements of World War II encouraged developments, which created a need for high-performance materials and helped speed the development of ceramic science and engineering. Throughout the 1960s and 1970s, new types of ceramics were developed in response to advances in atomic energy, electronics, communications, and space travel. The discovery of ceramic superconductors in 1986 has spurred intense research to develop superconducting ceramic parts for electronic devices, electric motors, and transportation equipment.

There is an increasing need in the military sector for high-strength, robust materials which have the capability to transmit light around the visible (0.4–0.7 micrometers) and mid-infrared (1–5 micrometers) regions of the spectrum. These materials are needed for applications requiring transparent armour. Transparent armor is a material or system of materials designed to be optically transparent, yet protect from fragmentation or ballistic impacts. The primary requirement for a transparent armour system is to not only defeat the designated threat but also provide a multi-hit capability with minimized distortion of surrounding areas. Transparent armour windows must also be compatible with night vision equipment. New materials that are thinner, lightweight, and offer better ballistic performance are being sought.[3] Such solid-state components have found widespread use for various applications in the electro-optical field including: optical fibres for guided lightwave transmission, optical switches, laser amplifiers and lenses, hosts for solid-state lasers and optical window materials for gas lasers, and infrared (IR) heat seeking devices for missile guidance systems and IR night vision. [4]

Modern industry

Now a multibillion-dollar a year industry, ceramic engineering and research has established itself as an important field of science. Applications continue to expand as researchers develop new kinds of ceramics to serve different purposes.[1][5]

- Zirconium dioxide ceramics are used in the manufacture of knives. The blade of the ceramic knife will stay sharp for much longer than that of a steel knife, although it is more brittle and can be snapped by dropping it on a hard surface.

- Ceramics such as alumina, boron carbide and silicon carbide have been used in bulletproof vests to repel small arms rifle fire. Such plates are known commonly as trauma plates. Similar material is used to protect cockpits of some military aircraft, because of the low weight of the material.

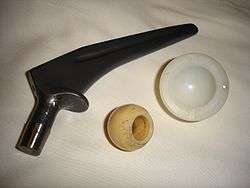

- Silicon nitride parts are used in ceramic ball bearings. Their higher hardness means that they are much less susceptible to wear and can offer more than triple lifetimes. They also deform less under load meaning they have less contact with the bearing retainer walls and can roll faster. In very high speed applications, heat from friction during rolling can cause problems for metal bearings; problems which are reduced by the use of ceramics. Ceramics are also more chemically resistant and can be used in wet environments where steel bearings would rust. The major drawback to using ceramics is a significantly higher cost. In many cases their electrically insulating properties may also be valuable in bearings.

- In the early 1980s, Toyota researched production of an adiabatic ceramic engine which can run at a temperature of over 6000 °F (3300 °C). Ceramic engines do not require a cooling system and hence allow a major weight reduction and therefore greater fuel efficiency. Fuel efficiency of the engine is also higher at high temperature, as shown by Carnot's theorem. In a conventional metallic engine, much of the energy released from the fuel must be dissipated as waste heat in order to prevent a meltdown of the metallic parts. Despite all of these desirable properties, such engines are not in production because the manufacturing of ceramic parts in the requisite precision and durability is difficult. Imperfection in the ceramic leads to cracks, which can lead to potentially dangerous equipment failure. Such engines are possible in laboratory settings, but mass-production is not feasible with current technology.

- Work is being done in developing ceramic parts for gas turbine engines. Currently, even blades made of advanced metal alloys used in the engines' hot section require cooling and careful limiting of operating temperatures. Turbine engines made with ceramics could operate more efficiently, giving aircraft greater range and payload for a set amount of fuel.

- Recently, there have been advances in ceramics which include bio-ceramics, such as dental implants and synthetic bones. Hydroxyapatite, the natural mineral component of bone, has been made synthetically from a number of biological and chemical sources and can be formed into ceramic materials. Orthopaedic implants made from these materials bond readily to bone and other tissues in the body without rejection or inflammatory reactions. Because of this, they are of great interest for gene delivery and tissue engineering scaffolds. Most hydroxyapatite ceramics are very porous and lack mechanical strength and are used to coat metal orthopaedic devices to aid in forming a bond to bone or as bone fillers. They are also used as fillers for orthopaedic plastic screws to aid in reducing the inflammation and increase absorption of these plastic materials. Work is being done to make strong, fully dense nano crystalline hydroxyapatite ceramic materials for orthopaedic weight bearing devices, replacing foreign metal and plastic orthopaedic materials with a synthetic, but naturally occurring, bone mineral. Ultimately these ceramic materials may be used as bone replacements or with the incorporation of protein collagens, synthetic bones.

- High-tech ceramic is used in watch-making for producing watch cases. The material is valued by watchmakers for its light weight, scratch-resistance, durability and smooth touch. IWC is one of the brands that initiated the use of ceramic in watch-making. The case of the IWC 2007 Top Gun edition of the Pilot's Watch Double chronograph is crafted in high-tech black ceramic.[6]

Glass-ceramics

Glass-ceramic materials share many properties with both glasses and ceramics. Glass-ceramics have an amorphous phase and one or more crystalline phases and are produced by a so-called "controlled crystallization", which is typically avoided in glass manufacturing. Glass-ceramics often contain a crystalline phase which constitutes anywhere from 30% [m/m] to 90% [m/m] of its composition by volume, yielding an array of materials with interesting thermomechanical properties.[5]

In the processing of glass-ceramics, molten glass is cooled down gradually before reheating and annealing. In this heat treatment the glass partly crystallizes. In many cases, so-called 'nucleation agents' are added in order to regulate and control the crystallization process. Because there is usually no pressing and sintering, glass-ceramics do not contain the volume fraction of porosity typically present in sintered ceramics.[1]

The term mainly refers to a mix of lithium and aluminosilicates which yields an array of materials with interesting thermomechanical properties. The most commercially important of these have the distinction of being impervious to thermal shock. Thus, glass-ceramics have become extremely useful for countertop cooking. The negative thermal expansion coefficient (TEC) of the crystalline ceramic phase can be balanced with the positive TEC of the glassy phase. At a certain point (~70% crystalline) the glass-ceramic has a net TEC near zero. This type of glass-ceramic exhibits excellent mechanical properties and can sustain repeated and quick temperature changes up to 1000 °C.[1][5]

Processing steps

The traditional ceramic process generally follows this sequence: Milling → Batching → Mixing → Forming → Drying → Firing → Assembly.[7][8] [9][10]

- Milling is the process by which materials are reduced from a large size to a smaller size. Milling may involve breaking up cemented material (in which case individual particles retain their shape) or pulverization (which involves grinding the particles themselves to a smaller size). Milling is generally done by mechanical means, including attrition (which is particle-to-particle collision that results in agglomerate break up or particle shearing), compression (which applies a forces that results in fracturing), and impact (which employs a milling medium or the particles themselves to cause fracturing). Attrition milling equipment includes the wet scrubber (also called the planetary mill or wet attrition mill), which has paddles in water creating vortexes in which the material collides and break up. Compression mills include the jaw crusher, roller crusher and cone crusher. Impact mills include the ball mill, which has media that tumble and fracture the material. Shaft impactors cause particle-to particle attrition and compression.

- Batching is the process of weighing the oxides according to recipes, and preparing them for mixing and drying.

- Mixing occurs after batching and is performed with various machines, such as dry mixing ribbon mixers (a type of cement mixer), Mueller mixers, and pug mills. Wet mixing generally involves the same equipment.

- Forming is making the mixed material into shapes, ranging from toilet bowls to spark plug insulators. Forming can involve: (1) Extrusion, such as extruding "slugs" to make bricks, (2) Pressing to make shaped parts, (3) Slip casting, as in making toilet bowls, wash basins and ornamentals like ceramic statues. Forming produces a "green" part, ready for drying. Green parts are soft, pliable, and over time will lose shape. Handling the green product will change its shape. For example, a green brick can be "squeezed", and after squeezing it will stay that way.

- Drying is removing the water or binder from the formed material. Spray drying is widely used to prepare powder for pressing operations. Other dryers are tunnel dryers and periodic dryers. Controlled heat is applied in this two-stage process. First, heat removes water. This step needs careful control, as rapid heating causes cracks and surface defects. The dried part is smaller than the green part, and is brittle, necessitating careful handling, since a small impact will cause crumbling and breaking.

- Sintering is where the dried parts pass through a controlled heating process, and the oxides are chemically changed to cause bonding and densification. The fired part will be smaller than the dried part.

Forming methods

Ceramic forming techniques include throwing, slipcasting, tape casting, freeze-casting, injection moulding, dry pressing, isostatic pressing, hot isostatic pressing (HIP) and others. Methods for forming ceramic powders into complex shapes are desirable in many areas of technology. Such methods are required for producing advanced, high-temperature structural parts such as heat engine components and turbines. Materials other than ceramics which are used in these processes may include: wood, metal, water, plaster and epoxy—most of which will be eliminated upon firing.[7]

These forming techniques are well known for providing tools and other components with dimensional stability, surface quality, high (near theoretical) density and microstructural uniformity. The increasing use and diversity of speciality forms of ceramics adds to the diversity of process technologies to be used.[7]

Thus, reinforcing fibres and filaments are mainly made by polymer, sol-gel, or CVD processes, but melt processing also has applicability. The most widely used speciality form is layered structures, with tape casting for electronic substrates and packages being pre-eminent. Photo-lithography is of increasing interest for precise patterning of conductors and other components for such packaging. Tape casting or forming processes are also of increasing interest for other applications, ranging from open structures such as fuel cells to ceramic composites.[7]

The other major layer structure is coating, where melt spraying is very important, but chemical and physical vapour deposition and chemical (e.g., sol-gel and polymer pyrolysis) methods are all seeing increased use. Besides open structures from formed tape, extruded structures, such as honeycomb catalyst supports, and highly porous structures, including various foams, for example, reticulated foam, are of increasing use.[7]

Densification of consolidated powder bodies continues to be achieved predominantly by (pressureless) sintering. However, the use of pressure sintering by hot pressing is increasing, especially for non-oxides and parts of simple shapes where higher quality (mainly microstructural homogeneity) is needed, and larger size or multiple parts per pressing can be an advantage.[7]

The sintering process

The principles of sintering-based methods are simple ("sinter" has roots in the English "cinder"). The firing is done at a temperature below the melting point of the ceramic. Once a roughly-held-together object called a "green body" is made, it is baked in a kiln, where atomic and molecular diffusion processes give rise to significant changes in the primary microstructural features. This includes the gradual elimination of porosity, which is typically accompanied by a net shrinkage and overall densification of the component. Thus, the pores in the object may close up, resulting in a denser product of significantly greater strength and fracture toughness.

Another major change in the body during the firing or sintering process will be the establishment of the polycrystalline nature of the solid. This change will introduce some form of grain size distribution, which will have a significant impact on the ultimate physical properties of the material. The grain sizes will either be associated with the initial particle size, or possibly the sizes of aggregates or particle clusters which arise during the initial stages of processing.

The ultimate microstructure (and thus the physical properties) of the final product will be limited by and subject to the form of the structural template or precursor which is created in the initial stages of chemical synthesis and physical forming. Hence the importance of chemical powder and polymer processing as it pertains to the synthesis of industrial ceramics, glasses and glass-ceramics.

There are numerous possible refinements of the sintering process. Some of the most common involve pressing the green body to give the densification a head start and reduce the sintering time needed. Sometimes organic binders such as polyvinyl alcohol are added to hold the green body together; these burn out during the firing (at 200–350 °C). Sometimes organic lubricants are added during pressing to increase densification. It is common to combine these, and add binders and lubricants to a powder, then press. (The formulation of these organic chemical additives is an art in itself. This is particularly important in the manufacture of high performance ceramics such as those used by the billions for electronics, in capacitors, inductors, sensors, etc.)

A slurry can be used in place of a powder, and then cast into a desired shape, dried and then sintered. Indeed, traditional pottery is done with this type of method, using a plastic mixture worked with the hands. If a mixture of different materials is used together in a ceramic, the sintering temperature is sometimes above the melting point of one minor component – a liquid phase sintering. This results in shorter sintering times compared to solid state sintering.[11]

Strength of ceramics

A material's strength is dependent on its microstructure. The engineering processes to which a material is subjected can alter its microstructure. The variety of strengthening mechanisms that alter the strength of a material include the mechanism of grain boundary strengthening. Thus, although yield strength is maximized with decreasing grain size, ultimately, very small grain sizes make the material brittle. Considered in tandem with the fact that the yield strength is the parameter that predicts plastic deformation in the material, one can make informed decisions on how to increase the strength of a material depending on its microstructural properties and the desired end effect.

The relation between yield stress and grain size is described mathematically by the Hall-Petch equation which is

where ky is the strengthening coefficient (a constant unique to each material), σo is a materials constant for the starting stress for dislocation movement (or the resistance of the lattice to dislocation motion), d is the grain diameter, and σy is the yield stress.

Theoretically, a material could be made infinitely strong if the grains are made infinitely small. This is, unfortunately, impossible because the lower limit of grain size is a single unit cell of the material. Even then, if the grains of a material are the size of a single unit cell, then the material is in fact amorphous, not crystalline, since there is no long range order, and dislocations can not be defined in an amorphous material. It has been observed experimentally that the microstructure with the highest yield strength is a grain size of about 10 nanometres, because grains smaller than this undergo another yielding mechanism, grain boundary sliding.[12] Producing engineering materials with this ideal grain size is difficult because of the limitations of initial particle sizes inherent to nanomaterials and nanotechnology.

Theory of chemical processing

Microstructural uniformity

In the processing of fine ceramics, the irregular particle sizes and shapes in a typical powder often lead to non-uniform packing morphologies that result in packing density variations in the powder compact. Uncontrolled agglomeration of powders due to attractive van der Waals forces can also give rise to in microstructural inhomogeneities.[7][13]

Differential stresses that develop as a result of non-uniform drying shrinkage are directly related to the rate at which the solvent can be removed, and thus highly dependent upon the distribution of porosity. Such stresses have been associated with a plastic-to-brittle transition in consolidated bodies,[14] and can yield to crack propagation in the unfired body if not relieved.

In addition, any fluctuations in packing density in the compact as it is prepared for the kiln are often amplified during the sintering process, yielding inhomogeneous densification.[15][16] Some pores and other structural defects associated with density variations have been shown to play a detrimental role in the sintering process by growing and thus limiting end-point densities.[17] Differential stresses arising from inhomogeneous densification have also been shown to result in the propagation of internal cracks, thus becoming the strength-controlling flaws.[18]

It would therefore appear desirable to process a material in such a way that it is physically uniform with regard to the distribution of components and porosity, rather than using particle size distributions which will maximize the green density. The containment of a uniformly dispersed assembly of strongly interacting particles in suspension requires total control over particle-particle interactions. Monodisperse colloids provide this potential.[19]

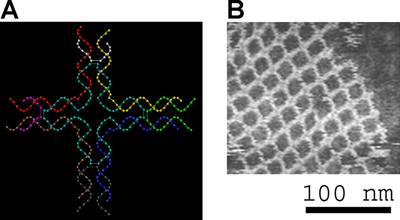

Monodisperse powders of colloidal silica, for example, may therefore be stabilized sufficiently to ensure a high degree of order in the colloidal crystal or polycrystalline colloidal solid which results from aggregation. The degree of order appears to be limited by the time and space allowed for longer-range correlations to be established.[20][21]

Such defective polycrystalline colloidal structures would appear to be the basic elements of submicrometer colloidal materials science, and, therefore, provide the first step in developing a more rigorous understanding of the mechanisms involved in microstructural evolution in inorganic systems such as polycrystalline ceramics.

Self-assembly

Self-assembly is the most common term in use in the modern scientific community to describe the spontaneous aggregation of particles (atoms, molecules, colloids, micelles, etc.) without the influence of any external forces. Large groups of such particles are known to assemble themselves into thermodynamically stable, structurally well-defined arrays, quite reminiscent of one of the 7 crystal systems found in metallurgy and mineralogy (e.g. face-centred cubic, body-centred cubic, etc.). The fundamental difference in equilibrium structure is in the spatial scale of the unit cell (or lattice parameter) in each particular case.

Thus, self-assembly is emerging as a new strategy in chemical synthesis and nanotechnology. Molecular self-assembly has been observed in various biological systems and underlies the formation of a wide variety of complex biological structures. Molecular crystals, liquid crystals, colloids, micelles, emulsions, phase-separated polymers, thin films and self-assembled monolayers all represent examples of the types of highly ordered structures which are obtained using these techniques. The distinguishing feature of these methods is self-organization in the absence of any external forces.

In addition, the principal mechanical characteristics and structures of biological ceramics, polymer composites, elastomers, and cellular materials are being re-evaluated, with an emphasis on bioinspired materials and structures. Traditional approaches focus on design methods of biological materials using conventional synthetic materials. This includes an emerging class of mechanically superior biomaterials based on microstructural features and designs found in nature. The new horizons have been identified in the synthesis of bioinspired materials through processes that are characteristic of biological systems in nature. This includes the nanoscale self-assembly of the components and the development of hierarchical structures.[20][21][23]

Ceramic composites

Substantial interest has arisen in recent years in fabricating ceramic composites. While there is considerable interest in composites with one or more non-ceramic constituents, the greatest attention is on composites in which all constituents are ceramic. These typically comprise two ceramic constituents: a continuous matrix, and a dispersed phase of ceramic particles, whiskers, or short (chopped) or continuous ceramic fibres. The challenge, as in wet chemical processing, is to obtain a uniform or homogeneous distribution of the dispersed particle or fibre phase.[24] [25]

Consider first the processing of particulate composites. The particulate phase of greatest interest is tetragonal zirconia because of the toughening that can be achieved from the phase transformation from the metastable tetragonal to the monoclinic crystalline phase, aka transformation toughening. There is also substantial interest in dispersion of hard, non-oxide phases such as SiC, TiB, TiC, boron, carbon and especially oxide matrices like alumina and mullite. There is also interest too incorporating other ceramic particulates, especially those of highly anisotropic thermal expansion. Examples include Al2O3, TiO2, graphite, and boron nitride.[24][25]

In processing particulate composites, the issue is not only homogeneity of the size and spatial distribution of the dispersed and matrix phases, but also control of the matrix grain size. However, there is some built-in self-control due to inhibition of matrix grain growth by the dispersed phase. Particulate composites, though generally offer increased resistance to damage, failure, or both, are still quite sensitive to inhomogeneities of composition as well as other processing defects such as pores. Thus they need good processing to be effective.[1][5]

Particulate composites have been made on a commercial basis by simply mixing powders of the two constituents. Although this approach is inherently limited in the homogeneity that can be achieved, it is the most readily adaptable for existing ceramic production technology. However, other approaches are of interest.[1][5]

From the technological standpoint, a particularly desirable approach to fabricating particulate composites is to coat the matrix or its precursor onto fine particles of the dispersed phase with good control of the starting dispersed particle size and the resultant matrix coating thickness. One should in principle be able to achieve the ultimate in homogeneity of distribution and thereby optimize composite performance. This can also have other ramifications, such as allowing more useful composite performance to be achieved in a body having porosity, which might be desired for other factors, such as limiting thermal conductivity.

There are also some opportunities to utilize melt processing for fabrication of ceramic, particulate, whisker and short-fibre, and continuous-fibre composites. Clearly, both particulate and whisker composites are conceivable by solid-state precipitation after solidification of the melt. This can also be obtained in some cases by sintering, as for precipitation-toughened, partially stabilized zirconia. Similarly, it is known that one can directionally solidify ceramic eutectic mixtures and hence obtain uniaxially aligned fibre composites. Such composite processing has typically been limited to very simple shapes and thus suffers from serious economic problems due to high machining costs.[24][25]

Clearly, there are possibilities of using melt casting for many of these approaches. Potentially even more desirable is using melt-derived particles. In this method, quenching is done in a solid solution or in a fine eutectic structure, in which the particles are then processed by more typical ceramic powder processing methods into a useful body. There have also been preliminary attempts to use melt spraying as a means of forming composites by introducing the dispersed particulate, whisker, or fibre phase in conjunction with the melt spraying process.

Other methods besides melt infiltration to manufacture ceramic composites with long fibre reinforcement are chemical vapour infiltration and the infiltration of fibre preforms with organic precursor, which after pyrolysis yield an amorphous ceramic matrix, initially with a low density. With repeated cycles of infiltration and pyrolysis one of those types of ceramic matrix composites is produced. Chemical vapour infiltration is used to manufacture carbon/carbon and silicon carbide reinforced with carbon or silicon carbide fibres.

Besides many process improvements, the first of two major needs for fibre composites is lower fibre costs. The second major need is fibre compositions or coatings, or composite processing, to reduce degradation that results from high-temperature composite exposure under oxidizing conditions.[24][25]

Applications

The products of technical ceramics include tiles used in the Space Shuttle program, gas burner nozzles, ballistic protection, nuclear fuel uranium oxide pellets, bio-medical implants, jet engine turbine blades, and missile nose cones.

Its products are often made from materials other than clay, chosen for their particular physical properties. These may be classified as follows:

- Oxides: silica, alumina, zirconia

- Non-oxides: carbides, borides, nitrides, silicides

- Composites: particulate or whisker reinforced matrices, combinations of oxides and non-oxides (e.g. polymers).

Ceramics can be used in many technological industries. One application is the ceramic tiles on NASA's Space Shuttle, used to protect it and the future supersonic space planes from the searing heat of re-entry into the Earth's atmosphere. They are also used widely in electronics and optics. In addition to the applications listed here, ceramics are also used as a coating in various engineering cases. An example would be a ceramic bearing coating over a titanium frame used for an aircraft. Recently the field has come to include the studies of single crystals or glass fibres, in addition to traditional polycrystalline materials, and the applications of these have been overlapping and changing rapidly.

Aerospace

- Engines; Shielding a hot running aircraft engine from damaging other components.

- Airframes; Used as a high-stress, high-temp and lightweight bearing and structural component.

- Missile nose-cones; Shielding the missile internals from heat.

- Space Shuttle tiles

- Space-debris ballistic shields – ceramic fiber woven shields offer better protection to hypervelocity (~7 km/s) particles than aluminium shields of equal weight.[26]

- Rocket nozzles, withstands and focuses the exhaust of the rocket booster.

- Unmanned Air Vehicles; Implications of ceramic engine utilization in aeronautical applications (such as Unmanned Air Vehicles) may result in enhanced performance characteristics and less operational costs.[27]

Biomedical

- Artificial bone; Dentistry applications, teeth.

- Biodegradable splints; Reinforcing bones recovering from osteoporosis

- Implant material

Electronics

Optical

- Optical fibres, guided lightwave transmission

- Switches

- Laser amplifiers

- Lenses

- Infrared heat-seeking devices

Automotive

Biomaterials

Silicification is quite common in the biological world and occurs in bacteria, single-celled organisms, plants, and animals (invertebrates and vertebrates). Crystalline minerals formed in such environment often show exceptional physical properties (e.g. strength, hardness, fracture toughness) and tend to form hierarchical structures that exhibit microstructural order over a range of length or spatial scales. The minerals are crystallized from an environment that is undersaturated with respect to silicon, and under conditions of neutral pH and low temperature (0–40 °C). Formation of the mineral may occur either within or outside of the cell wall of an organism, and specific biochemical reactions for mineral deposition exist that include lipids, proteins and carbohydrates.

Most natural (or biological) materials are complex composites whose mechanical properties are often outstanding, considering the weak constituents from which they are assembled. These complex structures, which have risen from hundreds of million years of evolution, are inspiring the design of novel materials with exceptional physical properties for high performance in adverse conditions. Their defining characteristics such as hierarchy, multifunctionality, and the capacity for self-healing, are currently being investigated.[29]

The basic building blocks begin with the 20 amino acids and proceed to polypeptides, polysaccharides, and polypeptides–saccharides. These, in turn, compose the basic proteins, which are the primary constituents of the ‘soft tissues’ common to most biominerals. With well over 1000 proteins possible, current research emphasizes the use of collagen, chitin, keratin, and elastin. The ‘hard’ phases are often strengthened by crystalline minerals, which nucleate and grow in a biomediated environment that determines the size, shape and distribution of individual crystals. The most important mineral phases have been identified as hydroxyapatite, silica, and aragonite. Using the classification of Wegst and Ashby, the principal mechanical characteristics and structures of biological ceramics, polymer composites, elastomers, and cellular materials have been presented. Selected systems in each class are being investigated with emphasis on the relationship between their microstructure over a range of length scales and their mechanical response.

Thus, the crystallization of inorganic materials in nature generally occurs at ambient temperature and pressure. Yet the vital organisms through which these minerals form are capable of consistently producing extremely precise and complex structures. Understanding the processes in which living organisms control the growth of crystalline minerals such as silica could lead to significant advances in the field of materials science, and open the door to novel synthesis techniques for nanoscale composite materials, or nanocomposites.

High-resolution SEM observations were performed of the microstructure of the mother-of-pearl (or nacre) portion of the abalone shell. Those shells exhibit the highest mechanical strength and fracture toughness of any non-metallic substance known. The nacre from the shell of the abalone has become one of the more intensively studied biological structures in materials science. Clearly visible in these images are the neatly stacked (or ordered) mineral tiles separated by thin organic sheets along with a macrostructure of larger periodic growth bands which collectively form what scientists are currently referring to as a hierarchical composite structure. (The term hierarchy simply implies that there are a range of structural features which exist over a wide range of length scales).[30]

Future developments reside in the synthesis of bio-inspired materials through processing methods and strategies that are characteristic of biological systems. These involve nanoscale self-assembly of the components and the development of hierarchical structures.[20][21][23][31]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Kingery, W.D., Bowen, H.K., and Uhlmann, D.R., Introduction to Ceramics, p. 690 (Wiley-Interscience, 2nd Edition, 2006)

- ↑ von Hippel; A. R. (1954). "Ceramics". Dielectric Materials and Applications. Technology Press (M.I.T.) and John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 1-58053-123-7.

- ↑ Patel, Parimal J. (2000). "Transparent ceramics for armour and EM window applications". Proceedings of SPIE. 4102. p. 1. doi:10.1117/12.405270.

- ↑ Harris, D.C., "Materials for Infrared Windows and Domes: Properties and Performance", SPIE PRESS Monograph, Vol. PM70 (Int. Society of Optical Engineers, Bellingham WA, 2009) ISBN 978-0-8194-5978-7

- 1 2 3 4 5 Richerson, D.W., Modern Ceramic Engineering, 2nd Ed., (Marcel Dekker Inc., 1992) ISBN 0-8247-8634-3.

- ↑ Ceramic in Watch-making. Watches.infoniac.com (9 January 2008). Retrieved on 2011-12-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Onoda, G.Y. Jr.; Hench, L.L., eds. (1979). Ceramic Processing Before Firing. New York: Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Brinker, C.J.; Scherer, G.W. (1990). Sol-Gel Science: The Physics and Chemistry of Sol-Gel Processing. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-134970-5.

- ↑ Hench, L.L.; West, J.K. (1990). "The Sol-Gel Process". Chemical Reviews. 90: 33. doi:10.1021/cr00099a003.

- ↑ Klein, L. (1994). Sol-Gel Optics: Processing and Applications. Springer Verlag. ISBN 0-7923-9424-0.

- ↑ Rahaman, M.N., Ceramic Processing and Sintering, 2nd Ed. (Marcel Dekker Inc., 2003) ISBN 0-8247-0988-8

- ↑ Schuh, Christopher; Nieh, T.G. (2002). "Hardness and Abrasion Resistance of Nanocrystalline Nickel Alloys Near the Hall-Petch Breakdown Regime" (PDF). Mat. Res. Soc. Symp. Proc. 740. doi:10.1557/PROC-740-I1.8.

- ↑ Aksay, I.A., Lange, F.F., Davis, B.I.; Lange; Davis (1983). "Uniformity of Al2O3-ZrO2 Composites by Colloidal Filtration". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 66 (10): C–190. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb10550.x.

- ↑ Franks, G.V.; Lange, F.F. (1996). "Plastic-to-Brittle Transition of Saturated, Alumina Powder Compacts". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 79 (12): 3161. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1996.tb08091.x.

- ↑ Evans, A.G.; Davidge, R.W. (1969). "Strength and fracture of fully dense polycrystalline magnesium oxide". Phil. Mag. 20 (164): 373. Bibcode:1969PMag...20..373E. doi:10.1080/14786436908228708.

- ↑ Evans, A.G.; Davidge, R.W. (1970). "Strength and fracture of fully dense polycrystalline magnesium oxide". J. Mat. Sci. 5 (4): 314. Bibcode:1970JMatS...5..314E. doi:10.1007/BF02397783.

- ↑ Lange, F.F.; Metcalf, M. (1983). "Processing-Related Fracture Origins in Al2O3/ZrO2 Composites II: Agglomerate Motion and Crack-like Internal Surfaces Caused by Differential Sintering". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 66 (6): 398. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1983.tb10069.x.

- ↑ Evans, A.G. (1987). "Considerations of Inhomogeneity Effects in Sintering". J. Am. Ceram. Soc. 65 (10): 497. doi:10.1111/j.1151-2916.1982.tb10340.x.

- ↑ Mangels, J.A.; Messing, G.L., Eds. (1984). "Microstructural Control Through Colloidal Consolidation". Advances in Ceramics: Forming of Ceramics. 9: 94.

- 1 2 3 Whitesides, G.M.; et al. (1991). "Molecular Self-Assembly and Nanochemistry: A Chemical Strategy for the Synthesis of Nanostructures". Science. 254 (5036): 1312–9. Bibcode:1991Sci...254.1312W. doi:10.1126/science.1962191. PMID 1962191.

- 1 2 3 Dubbs D. M, Aksay I.A.; Aksay (2000). "Self-Assembled Ceramics". Annu. Rev. Phys. Chem. 51: 601–22. Bibcode:2000ARPC...51..601D. doi:10.1146/annurev.physchem.51.1.601. PMID 11031294.

- ↑ Dalgarno, S. J.; Tucker, SA; Bassil, DB; Atwood, JL (2005). "Fluorescent Guest Molecules Report Ordered Inner Phase of Host Capsules in Solution". Science. 309 (5743): 2037–9. Bibcode:2005Sci...309.2037D. doi:10.1126/science.1116579. PMID 16179474.

- 1 2 Ariga, K.; Hill, J. P.; Lee, M. V.; Vinu, A.; Charvet, R.; Acharya, S. (2008). "Challenges and breakthroughs in recent research on self-assembly". Science and Technology of Advanced Materials. 9 (1): 014109. Bibcode:2008STAdM...9a4109A. doi:10.1088/1468-6996/9/1/014109. PMC 5099804

. PMID 27877935.

. PMID 27877935. - 1 2 3 4 Hull, D. and Clyne, T.W. (1996) An Introduction to Composite Materials. Cambridge Solid State Science Series, Cambridge University Press

- 1 2 3 4 Barbero, E.J. (2010) Introduction to Composite Materials Design, 2nd Edn., CRC Press.

- ↑ Ceramic Fabric Offers Space Age Protection, 1994 Hypervelocity Impact Symposium

- ↑ Gohardani, A. S.; Gohardani, O. (2012). "Ceramic engine considerations for future aerospace propulsion". Aircraft Engineering and Aerospace Technology. 84 (2): 75. doi:10.1108/00022661211207884.

- ↑ Strong, M. (2004). "Protein Nanomachines". PLoS Biology. 2 (3): e73. doi:10.1371/journal.pbio.0020073. PMC 368168

. PMID 15024422.

. PMID 15024422. - ↑ Perry, C.C. (2003). "Silicification: The Processes by Which Organisms Capture and Mineralize Silica". Rev. Miner. Geochem. 54: 291. doi:10.2113/0540291.

- ↑ Meyers, M. A.; Chen, P. Y.; Lin, A. Y. M.; Seki, Y. (2008). "Biological materials: Structure and mechanical properties". Progress in Materials Science. 53: 1. doi:10.1016/j.pmatsci.2007.05.002.

- ↑ Heuer, A.H.; et al. (1992). "Innovative Materials Processing Strategies: A Biomimetic Approach". Science. 255 (5048): 1098. Bibcode:1992Sci...255.1098H. doi:10.1126/science.1546311.