Brush Park

|

Woodward East Historic District | |

|

Streetscape on Edmund Place | |

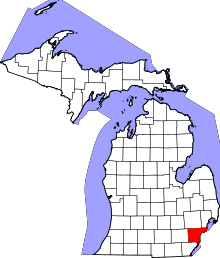

| Location |

Detroit, Michigan |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 42°20′43″N 83°3′9″W / 42.34528°N 83.05250°WCoordinates: 42°20′43″N 83°3′9″W / 42.34528°N 83.05250°W |

| Architect | Multiple |

| Architectural style | Late Victorian, French Renaissance Revival, Second Empire, Italianate, Other |

| NRHP Reference # | 75000973[1] |

| Significant dates | |

| Added to NRHP | January 21, 1975[2] |

| Designated MSHS | September 17, 1974[2] |

The Brush Park Historic District, frequently referred to as simply Brush Park, is a 22-block neighborhood located within Midtown Detroit, Michigan and designated by the city.[3][4] It is bounded by Mack Avenue on the north, Woodward Avenue on the west, Beaubien Street on the east, and the Fisher Freeway on the south.[5][6] The Woodward East Historic District, a smaller historic district completely encompassed by the larger Brush Park neighborhood, is located on Alfred, Edmund, and Watson Streets, from Brush Street to John R. Street, and is recognized by the National Register of Historic Places.[2][7]

Originally part of a French ribbon farm, Brush Park was developed beginning in the 1850s as an upscale residential neighborhood for Detroit's elite citizens by entrepreneur Edmund Askin Brush. Dozens of Victorian mansions were built there during the final decades of the nineteenth century, and Brush Park was nicknamed "Little Paris" due to its elegant architecture.[8] The neighborhood's heyday didn't last long, however: by the early twentieth century most of is affluent residents started moving to more modern, quieter districts, and Brush Park was quickly populated by members of Detroit's fast-growing working class. Severely affected by depopulation, blight and crime during the 1970s and 1980s, the neighborhood is currently experiencing restorations of its historic buildings and luring new residents.[9][10]

History

Early years

_Detroit%2C_p483_RESIDENCE_OF_PHILO_PARSONS%2C_530_WOODWARD_AVE._BUILT_IN_1876.jpg)

The land now occupied by the Brush Park district was originally part of a ribbon farm dating back to the French colonial period, initially conceded by Charles de la Boische, Marquis de Beauharnois to Laurence Eustache Gamelin for military services on May 1, 1747.[11][12][13][14] After the death of its second owner, Jacques Pilet, the farm was acquired by the prominent Barthe family, and in the late eighteenth century John Askin, an Irish fur trader and land speculator, obtained it through marriage with Marie-Archange Barthe.[15][12][16] In 1802 Askin's daughter Adelaide married Elijah Brush, a Vermont lawyer who would soon become Detroit's second mayor from its first incorporation;[17] on October 31, 1806, Elijah purchased the farm for $6000.[18]

Beginning in the 1850s, entrepreneur Edmund Askin Brush, son of Elijah, began developing his family's property, located conveniently close to downtown, into a neighborhood for Detroit's elite citizens.[16] The first street, named after Colonel John Winder, was opened in 1852; the other streets followed soon afterwards, and were mainly named after members of the Brush family (Adelaide, Edmund, Alfred, Eliot).[5][16] The area was developed with care: the land directly facing Woodward Avenue was subdivided into large and expensive lots, soon occupied by religious buildings and opulent mansions rivaling those built along East Jefferson Avenue and West Fort Street, while the land to the east was partitioned into relatively smaller, fifty feet wide parcels;[5][6][16] severe restrictions required the construction of high-end, elegant mansions,[19] giving a uniform and exclusive character to the neighborhood. In the late 19th century, Brush Park became known as the "Little Paris of the Midwest".[8][20]

Architects who designed these mansions included Henry T. Brush, George D. Mason, George W. Nettleton, and Albert Kahn. Homes were built in Brush Park beginning in the 1860s and peaking in the 1870s and 1880s; one of the last homes built was constructed in 1906 by Albert Kahn for his personal use. Other early residents of Brush Park included lumber baron David Whitney Jr. and his daughter, Grace Whitney Evans;[16] Joseph L. Hudson, founder of the eponymous department store;[5] Fulton Iron Works founder Delos Rice;[8] lumber baron Lucien S. Moore; banker Frederick Butler; merchant John P. Fiske; Dime Savings Bank president William Livingstone Jr.; and dry goods manufacturer Ransom Gillis.

In the 1890s the character of the subdivision began to change, as many prominent members of the local German Jewish community moved to Brush Park; this period of the neighborhood's history is recorded by the neoclassical Temple Beth-El, designed by Albert Kahn for the Reform Congregation and constructed in 1902.[21][16][22] Around the same time, Brush Park saw the construction of its first apartment buildings. One of the neighborhood's earliest examples of this type of structure was the Luben Apartments, built in 1901 by architect Edwin W. Gregory[16] and demolished in 2010.[23] The Luben featured large and sumptuous units, and its elaborate limestone façade blended with those of the surrounding mansions; however, the construction of apartment buildings undoubtedly represented a decrease in the quality of Brush Park's building stock.[16]

Decline

The neighborhood began to decline at the turn of the 20th century, when the advent of streetcars and then automobiles allowed prosperous citizens to live farther from downtown: early residents moved out, notably to up-and-coming districts such as Indian Village and Boston–Edison, and Brush Park became less fashionable.[5][8] The Woodward Avenue frontage rapidly lost its residential character, as the lavish mansions were demolished to make way for commercial buildings;[8] throughout the subdivision, homes were converted to apartments or rooming houses—often with the construction of two- and three-story rear additions—to accommodate workers of the booming automobile industry,[16] and dozens of structures were razed for surface parking lots. By 1921, all of the homes on Alfred Street were apartments or rooming houses.[24][25]

The Great Depression and the racial tensions of the 1940s (part of the 1943 race riot took place in the streets of Brush Park)[25] led to a rapid deterioration of the neighborhood. Longtime resident Russell McLauchlin described Brush Park's decline in the preface to his book Alfred Street (1946):

[Alfred Street] is now in what city-planners call a blighted area. The elms were long ago cut down. No representative of the old neighborfamilies remains. The houses, mostly standing as they stood a half-century ago, are dismal structures. Some have night-blooming grocery stores in their front yards. Some have boarded windows. All stand in bitter need of paint and repair. It is a desolate street; a scene of poverty and chop-fallen gloom; possibly of worse things.[26]

Starting in the 1960s, many of the buildings became unoccupied and fell into disrepair; however, the neighborhood maintained much of its historical integrity, and some attempts were made to preserve it. The first serious redevelopment plan in Brush Park's history was the Woodward East Renaissance project, planned to be completed in 1976, America's bicentennial year.[27] The ambitious plan included restoring the surviving historic mansions and erecting modern residential buildings on the empty lots, but it was left unrealized due to disorganization.[28] The area bounded by Alfred, Brush, Watson, and John R. Streets, named Woodward East Historic District, was designated a Michigan State Historic Site on September 17, 1974, and listed on the National Register of Historic Places on January 21, 1975;[2] the larger Brush Park Historic District, bounded by Woodward, Mack, Beaubien, and the Fisher Freeway, was established by the City of Detroit on January 23, 1980.[3] Despite these attempts to save what was left of the neighborhood's historic character, by the 1980s Brush Park had gradually fallen into a state of "nearly total abandonment and disintegration",[5] gaining a poor reputation as one of Detroit's most derelict areas. Abandoned buildings became targets for vandals and arsonists: as a result, dozens of structures were demolished by the City for security reasons. During the 19th century, around 300 homes were built in Brush Park, including 70 Victorian mansions; at present, about 80 original structures remain in the area. Notable buildings that were demolished include the Woodward Avenue Baptist Church (1887), razed in 1986,[29] and St. Patrick Catholic Church (1862), destroyed by fire in 1993.[30]

Revival

Brush Park's revival began in the 1990s and has since accelerated. New condominiums have been built in the southern part of the district, near the Fisher Freeway, and a number of the older mansions have been restored.[10] Several other historic houses have been stabilized and "mothballed" by the City of Detroit between 2005 and 2006, on the occasion of the Super Bowl XL played at the nearby Ford Field. A handful of other buildings still remain in a state of complete neglect, and are threatened with demolition.

The French Renaissance style William Livingstone House (1894)[16] on Eliot Street was one of Kahn's first commissions. The Red Cross intended to demolish the mansion, originally located west of John R. Street, to make way for their new building. Preservationists succeeded in successfully moving the Livingstone House about one block to the east.[31] Nevertheless, after this change of position some serious structural problems concerning the house's foundations caused the gradual collapse of the building. Artist Lowell Bioleau commemorated the William Livingstone House in a painting entitled Open House which he unveiled the day of its demolition September 15, 2007, underscoring preservationist efforts.[32]

On May 10, 2014, the historic First Unitarian Church caught fire under suspicious circumstances and was consequently demolished.[33] The building, which was designed by Donaldson and Meier and dated back to 1890, represents one of the greatest losses in Brush Park's recent history, since it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34]

Architecture

| Name[35] | Image | Year | Location | Style | Architect | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

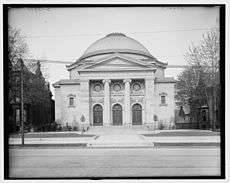

| Bonstelle Theatre |  |

1902 | 3424 Woodward Ave. | Beaux-Arts, Greek Revival | Albert Kahn, C. Howard Crane | In accordance with the wishes of rabbi Leo M. Franklin,[22] Albert Kahn designed this neoclassical temple on Woodward Avenue for Detroit's Jewish community. Groundbreaking began on November 25, 1901, with the ceremonial cornerstone laid on April 23, 1902.[36] After the construction of a new synagogue at 8801 Woodward, in 1925 the Temple Beth El was converted into a theater by C. Howard Crane;[21] the façade was later strongly altered with the 1936 Woodward widening. The structure – the oldest synagogue building in Detroit[21] – is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| Frederick Butler House |  |

1882 | 291 Edmund Pl. | French Renaissance Revival, Second Empire | William Scott & Co. | Built in 1882, the Frederick Butler House is a French Renaissance Second Empire style mansion containing 8,400 sq ft (780 m2); the original owner, Frederick Butler, was a banker.[16] It was restored and converted to condos in 2006.[9] The house, located within the Woodward East Historic District, is presently now as Edmund Place. |

| James V. Campbell House |  |

1877 | 261 Alfred St. | Italianate | James Valentine Campbell (1823–1890) was secretary of the Board of Regents of the University of Michigan, justice of the Michigan Supreme Court, and Marshall Professor of Law at the University of Michigan.[37] The house was occupied by the Campbell family from 1877 to 1891.[24] The building, pictured far left, is within the Woodward East Historic District. | |

| The Carlton | 1923 | 2915 John R. St. at Edmund | Beaux-Arts, Chicago School | Louis Kamper | Renovated as condominiums. | |

| Carola Building | 1912 | 78 Watson St. | Renaissance Revival | Renovated as condominiums. Pictured to the left of the Devon. | ||

| Lyman Cochrane House | 1870 | 216 Winder St. | Italianate | This house is a relatively rare example of residential Italianate architecture in Detroit.[38] It was originally built for eye doctor John F. Terry, but in 1871 was sold to Lyman Cochrane.[39] Cochrane was a state senator and Superior Court Judge,[40] serving in this capacity until his death in 1879.[41][42] | ||

| Crystal lofts | 1919 | 3100 Woodward Ave. at Watson | Art Deco | Originally constructed as a ballroom (the Crystal Palace),[43] the building was recently renovated as condominiums. The Art Deco façade was added in 1936.[44] | ||

| The Devon | 1905 | 64 Watson St. | Art Deco | |||

| J.P. Donaldson House | 1879 | 82 Alfred St. | Queen Anne | Mason & Rice; Gordon W. Lloyd (remodeling) | This house was built in 1879 for James P. Donaldson, a ship chandler. In 1892, David Charles Whitney (son of David Whitney Jr.) acquired the home, which was completely renovated by Gordon W. Lloyd.[45] At the time it was said to be one of the most substantial homes in Detroit and valued at $30,000 (today $750,000±).[46] The home had several other owners before becoming a rooming house;[46][47] in 2012 the building has been sold to a private buyer for $110,000. In the same year the mansion has been a movie set for the vampire film Only Lovers Left Alive, directed by Jim Jarmusch.[48] | |

| Clifford Elliot House |  |

1899 | 305 Eliot St. | Victorian, Edwardian | M.A. Edwards | Built in 1899 for Clifford Elliot, a wholesale grocery executive, this turn-of-the-century house exemplifies the transition from the Victorian design to the Edwardian style of architecture.[16] |

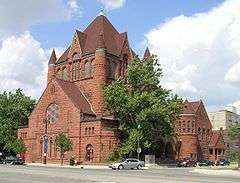

| First Presbyterian Church |  |

1889 | 2930 Woodward Ave. | Richardsonian Romanesque | George D. Mason | George D. Mason modeled the First Presbyterian Church after Henry Hobson Richardson's Trinity Church in Boston.[16] When Woodward was widened in 1936, the elaborately-carved entrance porch was moved from the Woodward façade to the Edmund Place side.[16] The church is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| John P. Fiske House | 1876 | 261 Edmund Pl. | Second Empire, French Renaissance Revival, Victorian | John P. Fiske was a Detroit merchant of china and crockery.[49] The house, located within the Woodward East Historic District, was designated a Michigan State Historic Site on August 18, 1988.[49] | ||

| Ransom Gillis House |  |

1876 | 205 Alfred St. at John R. | Venetian Gothic | Henry T. Brush & George D. Mason | This building has been heavily documented by John Kossik[50] and photographed by documentarian Camilo José Vergara.[51] The house, built between 1876 and 1878 for Ransom Gillis, a wholesale dry goods merchant,[51] is within the Woodward East Historic District. |

| Bernard Ginsburg House |  |

1898 | 236 Adelaide St. | Tudor Revival | George W. Nettleton & Albert Kahn | Bernard Ginsburg was an important figure in philanthropy, civic service, and the Jewish community in Detroit during the late 19th and early 20th century.[52] He commissioned architect Albert Kahn to design this house, one of Kahn's earliest works. Kahn went on to become well known in industrial and commercial architecture; the Ginsburg house and its English Renaissance style exhibited is typical of Kahn's early work.[16] The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| John Harvey House |  |

1887 | 97 Winder St. | Second Empire | John V. Smith | John Harvey was a pharmacist and philanthropist. The house contains 11,000 square feet (1,000 m2), eight marble fireplaces, and three-story staircase. Developers purchased the John Harvey House in 1986, renovated the structure, and, in 2005, opened it as the Inn at 97 Winder, a bed and breakfast.[53] The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| Hudson-Evans House |  |

1874 | 79 Alfred St. | Second Empire, French Renaissance Revival, Italianate | Unknown | Also known as the Joseph Lothian Hudson House or the Grace Whitney Evans House. Built in 1874[54] for shipowner Philo Wright, the house was a gift from David Whitney Jr. to his daughter Grace upon her marriage to John Evans in 1882.[16] It later became the Joseph L. Hudson family residence.[54] Listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| Albert Kahn House |  |

1906 | 208 Mack Ave. | English Renaissance | Albert Kahn | In 1906, architect Albert Kahn built a home for his personal use.[16] He lived in this mansion fronting Mack Avenue from 1906 until his death in 1942; the structure was later obtained by the Detroit Urban League, which still uses it today.[55] The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| George Ladve House | 1882 | 269 Edmund Pl. | Eastlake Victorian | Originally owned by George Ladve, 269 Edmund Pl., an Eastlake Victorian style mansion built in 1882 and restored in 2008, contains 7,400 sq ft (690 m2). Ladve had owned a carpet and upholstery company. In the late 1890s, the Frohlich family added a music room. Edward P. Frohlich was among the original philanthropists to the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. The house is within the Woodward East Historic District.[56] | ||

| Lucien S. Moore House | c. 1885 | 104 Edmund Pl. | French Renaissance Revival, Gothic Revival | Unknown | Originally owned by lumber baron Lucien S. Moore, 104 Edmund Place, built around 1885[16] in a French Renaissance Gothic Revival style and restored in 2006, has 7,000 sq ft (650 m2).[9][57] The Lucien Moore House restoration was featured December 27, 2005 by HGTV's restore America Initiative in partnership with the National Trust for Historic Preservation.[58][59] It may also be known as the Moorie Town House or The Edmund. | |

| Patterson Terrace | 1903 | 203-209-212 Erskine St. | Richardsonian Romanesque | In ruins, the structure needs a massive renovation. | ||

| H.P. Pulling House | 48 Edmund Pl. | Victorian | Henry Perry Pulling (1814–1890) was a doctor and the president of the Peninsular Bank from 1860 until its closure in 1870.[60][61] | |||

| Emanuel Schloss House | 1870 | 234 Winder St. | Second Empire | Emanuel Schloss was a dry goods merchant and haberdasher in Detroit.[62] In 1870, he built one of the best examples of a Second Empire home that still exists in Detroit.[62] The home has been restored and now operates as the 234 Winder Street Inn.[63] | ||

| Horace S. Tarbell House |  |

1869 | 227 Adelaide St. | Victorian, Italianate | One of the oldest existing structures in Brush Park, the house was constructed in 1869 and originally owned by Horace Sumner Tarbell (1838–1904), Michigan Superintendent of Public Instruction from 1876 to 1878.[64] Over the following decades, the property changed hands multiple times before being abandoned and falling into disrepair. | |

| Elisha Taylor House |  |

1870 | 59 Alfred St. | French Renaissance Revival, Second Empire, Victorian, Gothic Revival | Julius Hess | The Elisha Taylor House, with its French Renaissance Revival, Second Empire mansard roof, has distinct elements of Victorian and Gothic Revival style and was built in 1870[5] for William H. Craig, a Detroit land speculator.[16] In 1875, Craig sold the house to Elisha Taylor.[65] Taylor was a Detroit attorney who held many offices during his career, including City Attorney,[5] assistant Michigan Attorney General from 1837 to 1841, and Circuit Court Commissioner from 1846 to 1854.[65] The house is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[34] |

| Joseph F. Weber House | 1901 | 206 Eliot St. | Georgian | Unknown | Originally owned by lumber baron Joseph F. Weber, 206 Eliot is a Georgian style house.[16] | |

Education

Brush Park is within the Detroit Public Schools district. Residents are zoned to Spain Elementary School for K-8,[66][67] while they are zoned to Martin Luther King High School (9-12) for high school.[68]

References

- ↑ National Park Service (2008-04-15). "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service.

- 1 2 3 4 Woodward East Historic District from the state of Michigan. Retrieved on July 19, 2016 via Internet Archive.

- 1 2 Brush Park Historic District from the City of Detroit. Retrieved on July 14, 2016 via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Mullen, Ann (January 3, 2001). Brush Park and hope. Metro Times. Retrieved on June 14, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Hill & Gallagher 2002, p. 116.

- 1 2 Scott 2001, p. 48.

- ↑ Woodward East Historic District. Detroit Historical Society. Retrieved on January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Scott 2001, p. 49.

- 1 2 3 Pfeffer, Jaime (September 12, 2006). Falling for Brush Park. Model D Media. Retrieved on September 26, 2009.

- 1 2 Archambault, Dennis (February 14, 2006). Forging Bush Park. Model D Media. Retrieved on June 14, 2008.

- ↑ Farmer 1890, p. 36.

- 1 2 Jacobson 2002, p. 60.

- ↑ Lowrie 1834, p. 283.

- ↑ Quaife 1928, pp. 25–30.

- ↑ Ewen 1978, p. 59.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 Brush Park Historic District Final Report from the City of Detroit. Retrieved on January 25, 2016.

- ↑ Elijah Brush. Elmwood Cemetery.

- ↑ Jacobson 2002, p. 61.

- ↑ Brush Park Historic District. Detroit Historical Society. Retrieved on June 20, 2016.

- ↑ Piligian, Ellen (April 1, 2008). McMillin's Detroit. Model D Media. Retrieved on July 24, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Hill & Gallagher 2002, p. 110.

- 1 2 Temple Beth-El. Detroit1701.

- ↑ Luben Apartments. Detroiturbex.com. Retrieved on January 26, 2016.

- 1 2 Harding, Matt (December 28, 2013). Alfred St. in Brush Park: A microcosm of Detroit’s early decline. Motor City Muckraker. Retrieved on January 8, 2014.

- 1 2 Loomis, Bill (November 29, 2015). The idyllic neighborhood of Ransom Gillis. The Detroit News. Retrieved on June 14, 2016.

- ↑ McLauchlin 1946.

- ↑ Kossik 2010, p. 97.

- ↑ Kossik 2010, p. 98.

- ↑ Austin, Dan. Woodward Avenue Baptist Church. Historic Detroit. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ Austin, Dan. St. Patrick Catholic Church. Historic Detroit. Retrieved June 19, 2016.

- ↑ William Livingstone Residence. Detroit1701. Retrieved on January 12, 2011.

- ↑ Open House. Retrieved on September 26, 2009.

- ↑ Hutchinson, Derick (May 10, 2014). Historic Detroit church catches fire Saturday morning. ClickOnDetroit.com. Retrieved on May 12, 2014.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 National Register of Historic Places - Michigan: Wayne County. National Park Service. Retrieved on July 27, 2009.

- ↑ Historic sites online. Michigan Historic Preservation Office. Retrieved on December 11, 2007.

- ↑ Katz 1955, pp. 96–101.

- ↑ James Valentine Campbell. Bentley Historical Library. Retrieved on January 8, 2014.

- ↑ Lyman Cochrane House from the city of Detroit. Retrieved on July 19, 2016 via Internet Archive.

- ↑ Lyman Cochrane House. Detroit1701. Retrieved on September 7, 2009.

- ↑ "J. W. Weeks & Co.'s Annual City Directory of the Inhabitants, Business Firms, Incorporated Companies, Etc., of Detroit, for 1873–4". Detroit: J. W. Weeks & Co. p. 198.

- ↑ Detroit Free Press, February 6, 1879, p. 1.

- ↑ Carlisle 1890, pp. 411–412.

- ↑ Bjorn & Gallert 2001, p. 7.

- ↑ Crystal lofts. Detroit1701. Retrieved on December 2, 2011.

- ↑ "Bracing Up All Around". Detroit Freepress-ProQuest Historical Newspapers. 7 February 1892.

- 1 2 "Real Estate Budget". Detroit Free Press-ProQuest Historical Newspapers. 22 September 1901.

- ↑ ProQuest Sanborn Fire Insurance Maps Detroit Map 15, 1921

- ↑ Beshouri, Paul (January 14, 2013). 82 Alfred Street. Curbed Detroit. Retrieved on January 24, 2013.

- 1 2 John P. Fiske House from the city of Detroit. Retrieved on July 19, 2016 via Internet Archive.

- ↑ 63 Alfred Street: Where Capitalism Failed

- 1 2 Ransom Gillis Home. Detroit1701. Retrieved on September 7, 2009.

- ↑ Bernard Ginsburg House from the state of Michigan. Retrieved on July 19, 2016 via Internet Archive.

- ↑ The Largest Historic Mansion in Detroit's Brush Park Area Opens as a New, Prestigious Bed and Breakfast Inn (press release)

- 1 2 Hill & Gallagher 2002, p. 118.

- ↑ Albert Kahn Home. Detroit1701.

- ↑ Crain's Detroit House Party. Crain's Detroit Business. Retrieved on September 27, 2009.

- ↑ Lucien Moore House. Detroit1701. Retrieved on September 26, 2009.

- ↑ National Trust for Historic Preservation (December 27, 2005). Detroit’s Lucien Moore House Honored by HGTV Archived September 1, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved on May 3, 2009.

- ↑ Foster, Margaret (May–June 2005). Rebuilding Begins at Home: HGTV, Trust to focus on housing for Restore America's third year. Preservation Magazine. National Trust for Historic Preservation. Retrieved on September 27, 2009.

- ↑ Farmer 1884, p. 866.

- ↑ Farmer 1890, pp. 1227–28.

- 1 2 Emanuel Schloss House/234 Winder Street Inn. Detroit1701.

- ↑ 234 Winder Street Inn home page

- ↑ Putnam 1899, pp. 339–40.

- 1 2 The Elisha Taylor Home. Detroit1701.

- ↑ "Elementary School Boundary Map." Detroit Public Schools. Retrieved on October 20, 2009.

- ↑ "Middle School Boundary Map." Detroit Public Schools. Retrieved on October 20, 2009.

- ↑ "High School Boundary Map." Detroit Public Schools. Retrieved on October 20, 2009.

Bibliography

- Bjorn, Lars; Gallert, Jim (2001). Before Motown: a history of jazz in Detroit, 1920–60. Ann Arbor, MI: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472067656.

- Carlisle, Fred. (1890). Chronography of Notable Events in the History of the Northwest Territory and Wayne County. Detroit: O. S. Gulley, Bornman & Co., Printers.

- Ewen, Lynda Ann (1978). Corporate Power and Urban Crisis in Detroit. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. ISBN 1400871972.

- Farmer, Silas (1884). The History of Detroit and Michigan or The Metropolis Illustrated: A Chronological Cyclopædia of the Past and Present. Detroit: S. Farmer & Company.

- Farmer, Silas (1890). History of Detroit and Wayne County and Early Michigan: A Chronological Cyclopedia of the Past and Present. 1. Detroit: S. Farmer & Company.

- Farmer, Silas (1890). History of Detroit and Wayne County and Early Michigan: A Chronological Cyclopedia of the Past and Present. 2. Detroit: S. Farmer & Company.

- Hill, Eric J.; Gallagher, John (2002). AIA Detroit: The American Institute of Architects Guide to Detroit Architecture. Detroit: Wayne State University Press. ISBN 0-8143-3120-3.

- Jacobson, Judy (2002). Detroit River Connections: Historical and Biographical Sketches of the Eastern Great Lakes Border Region. Baltimore: Genealogical Publishing Company. ISBN 0-8063-4510-1.

- Katz, Irving I. (1955). The Beth El Story (with a History of Jews in Michigan Before 1850). Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

- Kossik, John (2010). 63 Alfred Street: Where Capitalism Failed. The Life and Times of a Venetian Gothic Mansion in Downtown Detroit. John Kossik.

- Lowrie, Walter, ed. (1834). American State Papers: Documents, Legislative and Executive, of the Congress of the United States. 1. Washington: Duff Green.

- McLauchlin, Russell J. (1946). Alfred Street. Detroit: Conjure House.

- Putnam, Daniel (1899). A History of the Michigan State Normal School (Now Normal College) at Ypsilanti, Michigan, 1849–1899. Ypsilanti, MI: The Scharf Tag, Label & Box Co.

- Quaife, Milo M., ed. (1928). The John Askin Papers, Volume I: 1747–1795. Detroit: Detroit Library Commission.

- Scott, Gene (2001). Detroit Beginnings: Early Villages and Old Neighborhoods. Detroit: Detroit Retired City Employees Association.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Brush Park Historic District. |

- Revitalization in Brush Park

- Dan Gilbert plans 337 new townhouses and apartments for Brush Park.—Detroit Free Press, May 7, 2015

- Detroit’s First Major Residential Development in Decades Blends Historic Preservation and New Construction in Brush Park.—City of Detroit, Press Release May 6, 2015

- Detroit Announces Plan to Preserve Iconic Brewster Wheeler Rec Center and Start Rebuilding Historic Neighborhood.—City of Detroit, Press Release April 14, 2015

- More higher-end apartments planned for Midtown, The Scott @ Brush Park.—Detroit Free Press, March 23, 2015