Conscription in the United States

| Conscription |

|---|

|

Military service |

| Conscription by country |

Conscription in the United States, commonly known as the draft, has been employed by the federal government of the United States in four conflicts: the American Civil War; World War I; World War II; and the Cold War (including both the Korean and Vietnam Wars). The third incarnation of the draft came into being in 1940 through the Selective Training and Service Act. It was the country's first peacetime draft.[1] From 1940 until 1973, during both peacetime and periods of conflict, men were drafted to fill vacancies in the United States Armed Forces that could not be filled through voluntary means. The draft was ended when the United States Armed Forces moved to an all-volunteer military force. However, the Selective Service System remains in place as a contingency plan; male civilians between the ages of 18 and 25 are required to register so that a draft can be readily resumed if needed.[2]

History

Colonial to 1862

In colonial times, the Thirteen Colonies used a militia system for defense. Colonial militia laws—and after independence those of the United States and the various states—required able-bodied males to enroll in the militia, to undergo a minimum of military training, and to serve for limited periods of time in war or emergency. This earliest form of conscription involved selective drafts of militiamen for service in particular campaigns. Following this system in its essentials, the Continental Congress in 1778 recommended that the states draft men from their militias for one year's service in the Continental army; this first national conscription was irregularly applied and failed to fill the Continental ranks.

For long-term operations, conscription was occasionally used when volunteers or paid substitutes were insufficient to raise the needed manpower. During the American Revolutionary War, the states sometimes drafted men for militia duty or to fill state Continental Army units, but the central government did not have the authority to conscript except for purposes of naval impressment. President James Madison and his Secretary of War James Monroe unsuccessfully attempted to create a national draft of 40,000 men during the War of 1812.[3] This proposal was fiercely criticized on the House floor by antiwar Congressman Daniel Webster of New Hampshire.[4]

| "The administration asserts the right to fill the ranks of the regular army by compulsion...Is this, sir, consistent with the character of a free government? Is this civil liberty? Is this the real character of our Constitution? No, sir, indeed it is not...Where is it written in the Constitution, in what article or section is it contained, that you may take children from their parents, and parents from their children, and compel them to fight the battles of any war, in which the folly or the wickedness of government may engage it? Under what concealment has this power lain hidden, which now for the first time comes forth, with a tremendous and baleful aspect, to trample down and destroy the dearest rights of personal liberty? |

| Daniel Webster (December 9, 1814 House of Representatives Address) |

Civil War

The United States first employed national conscription during the American Civil War. The vast majority of troops were volunteers; of the 2,100,000 Union soldiers, about 2% were draftees, and another 6% were substitutes paid by draftees.[5][6]

The Confederacy had far fewer inhabitants than the Union, and Confederate President Jefferson Davis proposed the first conscription act on March 28, 1862; it was passed into law the next month.[7] Resistance was both widespread and violent, with comparisons made between conscription and slavery.

Both sides permitted conscripts to hire substitutes to serve in their place. In the Union, many states and cities offered bounties and bonuses for enlistment. They also arranged to take credit against their draft quota by claiming freed slaves who enlisted in the Union Army.

Although both sides resorted to conscription, the system did not work effectively in either.[8] The Confederate Congress on April 16, 1862, passed an act requiring military service for three years from all males aged eighteen to thirty-five not legally exempt; it later extended the obligation. The U.S. Congress followed with the Militia Act of 1862 authorizing a militia draft within a state when it could not meet its quota with volunteers. This state-administered system failed in practice and in 1863 Congress passed the Enrollment Act, the first genuine national conscription law, setting up under the Union Army an elaborate machinery for enrolling and drafting men between twenty and forty-five years of age. Quotas were assigned in each state, the deficiencies in volunteers required to be met by conscription.

Still, men drafted could provide substitutes, and until mid-1864 could even avoid service by paying commutation money. Many eligible men pooled their money to cover the cost of any one of them drafted. Families used the substitute provision to select which member should go into the army and which would stay home. Of the 168,649 men procured for the Union Army through the draft, 117,986 were substitutes, leaving only 50,663 who had their personal services conscripted. There was much evasion and overt resistance to the draft, and the New York City draft riots were in direct response to the draft and were the first large-scale resistance against the draft in the United States.

The problem of Confederate desertion was aggravated by the inequitable inclinations of conscription officers and local judges. The three conscription acts of the Confederacy exempted certain categories, most notably the planter class, and enrolling officers and local judges often practiced favoritism, sometimes accepting bribes. Attempts to effectively deal with the issue were frustrated by conflict between state and local governments on the one hand and the national government of the Confederacy.[9]

World War I

In 1917 the administration of President Woodrow Wilson decided to rely primarily on conscription, rather than voluntary enlistment, to raise military manpower for World War I when only 73,000 volunteers enlisted out of the initial 1 million target in the first six weeks of the war.[10] One claimed motivation was to head off the former President, Theodore Roosevelt, who proposed to raise a volunteer division, which would upstage Wilson, but there is no evidence that even Roosevelt had the popularity to overcome the unpopular war.

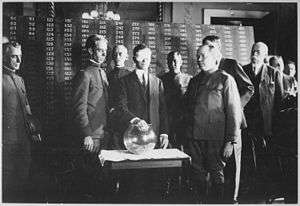

The Selective Service Act of 1917 was carefully drawn to remedy the defects in the Civil War system and—by allowing exemptions for dependency, essential occupations, and religious scruples—to place each man in his proper niche in a national war effort. The act established a "liability for military service of all male citizens"; authorized a selective draft of all those between 21 and 31 years of age (later from 18 to 45); and prohibited all forms of bounties, substitutions, or purchase of exemptions. Administration was entrusted to local boards composed of leading civilians in each community. These boards issued draft calls in order of numbers drawn in a national lottery and determined exemptions.

In 1917 10 million men were registered. This was deemed to be inadequate, so age ranges were increased and exemptions reduced, and so by the end of 1918 this increased to 24 million men that were registered with nearly 3 million inducted into the military services, with little of the resistance that characterized the Civil War, thanks to a huge campaign by the government to build support for the war, and shut down newspapers and magazines that published articles against the war.[11][12]

The draft was universal and included blacks on the same terms as whites, although they served in different units. In all 367,710 black Americans were drafted (13.0% of the total), compared to 2,442,586 white (86.9%). Along with a general opposition to American involvement in a foreign conflict, Southern farmers objected to unfair conscription practices that exempted members of the upper class and industrial workers.

Draft boards were localized and based their decisions on social class: the poorest were the most often conscripted because they were considered the most expendable at home. African-Americans in particular were often disproportionately drafted, though they generally were conscripted as laborers and not sent into combat to avoid the tensions that would arise from mixing races in military units. Forms of resistance ranged from peaceful protest to violent demonstrations and from humble letter-writing campaigns asking for mercy to radical newspapers demanding reform. The most common tactics were dodging and desertion, and many communities sheltered and defended their draft dodgers as political heroes.

Nearly half a million immigrants were drafted, which forced the military to develop training procedures that took ethnic differences into account. Military leaders invited Progressive reformers and ethnic group leaders to assist in formulating new military policies. The military attempted to socialize and Americanize young immigrant recruits, not by forcing "angloconformity", but by showing remarkable sensitivity and respect for ethnic values and traditions and a concern for the morale of immigrant troops. Sports activities, keeping immigrant groups together, newspapers in various languages, the assistance of bilingual officers, and ethnic entertainment programs were all employed.[13]

Opposition

The Conscription Act of 1917 was passed in June. Conscripts were court-martialed by the Army if they refused to wear uniforms, bear arms, perform basic duties, or submit to military authority. Convicted objectors were often given long sentences of 20 years in Fort Leavenworth.[14] In 1918 Secretary Baker created the Board of Inquiry to question the conscientious objectors' sincerity.[15] Military tribunals tried men found by the Board to be insincere for a variety of offenses, sentencing 17 to death, 142 to life imprisonment, and 345 to penal labor camps.[15]

In 1917, a number of radicals and anarchists, including Emma Goldman, challenged the new draft law in federal court, arguing that it was a direct violation of the Thirteenth Amendment's prohibition against slavery and involuntary servitude. The Supreme Court unanimously upheld the constitutionality of the draft act in the Selective Draft Law Cases on January 7, 1918. The decision said the Constitution gave Congress the power to declare war and to raise and support armies. The Court, relying partly on Vattel's The Law of Nations, emphasized the principle of the reciprocal rights and duties of citizens:[16]

It may not be doubted that the very conception of a just government and its duty to the citizen includes the reciprocal obligation of the citizen to render military service in case of need, and the right to compel it. To do more than state the proposition is absolutely unnecessary in view of the practical illustration afforded by the almost universal legislation to that effect now in force.

Conscription was unpopular from left-wing sectors at the start, with many Socialists jailed for "obstructing the recruitment or enlistment service". The most famous was Eugene Debs, head of the Socialist Party of America, who ran for president in 1920 from his Atlanta prison cell. He had his sentence commuted to time served and was released on December 25, 1921, by President Warren G. Harding.

The Industrial Workers of the World mobilized to obstruct the war effort through strikes in war-related industries and not registering.

Conscientious objectors

Conscientious objector exemptions were allowed for the Amish, Mennonites, Quakers, and Church of the Brethren only. All other religious and political objectors were forced to participate. Some 64,700 men claimed conscientious objector status; local draft boards certified 57,000, of whom 30,000 passed the physical and 21,000 were inducted into the U.S. Army. About 80% of the 21,000 decided to abandon their objection and take up arms, but 3,989 drafted objectors refused to serve. Most belonged to historically pacifist denominations, especially Quakers, Mennonites, and Moravian Brethren, as well as a few Seventh-day Adventists and Jehovah's Witnesses. About 15% were religious objectors from non-pacifist churches.[17]

Ben Salmon was a nationally known political activist who encouraged men not to register and personally refused to comply with the draft procedures. He rejected the Army Review Board proposal that he do noncombatant farm work. Sentenced to 25 years in prison, he again refused a proposed desk job. He was pardoned and released in November 1920 with a "dishonorable discharge".[18]

Interwar

The draft ended in 1918 but the Army designed the modern draft mechanism in 1926 and built it based on military needs despite an era of pacifism. Working where Congress would not, it gathered a cadre of officers for its nascent Joint Army-Navy Selective Service Committee, most of whom were commissioned based on social standing rather than military experience.[19] This effort did not receive congressionally approved funding until 1934 when Major Lewis B. Hershey was assigned to the organization. The passage of a conscription act was opposed by some, including Dorothy Day and George Barry O'Toole, who were concerned that such conscription would not provide adequate protection for the rights of conscientious objectors. However, much of Hershey's work was codified into law with the Selective Training and Service Act of 1940 (STSA).[20]

World War II

By the summer of 1940, as Germany conquered France, Americans supported the return of conscription. One national survey found that 67% of respondents believed that a German-Italian victory would endanger the United States, and that 71% supported "the immediate adoption of compulsory military training for all young men".[21] Similarly, a November 1942 survey of American high-school students found that 69% favored compulsory postwar military training.[22]

The World War I system served as a model for that of World War II. The 1940 STSA instituted national conscription in peacetime, requiring registration of all men between 18 and 45, with selection for one year's service by a national lottery. The term of service was extended by one year in August 1941. After Pearl Harbor the STSA was further amended (December 19, 1941), extending the term of service to the duration of the war and six months and requiring the registration of all men 18 to 65 years of age. In the massive draft of World War II, 49 million men were registered, 36 million classified , and 10 million inducted.[23] President Roosevelt's signing of the STSA on September 16, 1940, began the first peacetime draft in the United States. It also established the Selective Service System as an independent agency responsible for identifying and inducting young men into military service. Roosevelt named Hershey to head the Selective Service on July 31, 1941, where he remained until 1969.[20] This preparatory act came when other preparations, such as increased training and equipment production, had not yet been approved. Nevertheless, it served as the basis for the conscription programs that would continue to the present. The act set a cap of 900,000 men to be in training at any given time and limited military service to 12 months. An amendment increased this to 18 months in 1941. Later legislation amended the act to require all men from 18 to 65 to register with those aged 18 to 45 being immediately liable for induction. Service commitments for inductees were set at the length of the war plus six months.[24] As manpower need increased during World War II, draftees were inducted into both the Marine Corps and the Army.

By 1942, the SSS moved away from administrative selection by its more than 4,000 local boards to a system of lottery selection. Rather than filling quotas by local selection, the boards now ensured proper processing of men selected by the lottery.[19] On December 5, 1942, a presidential executive order changed the age range for the draft from 21–36 to 18–37, and mostly ended voluntary enlistment. Paul V. McNutt, head of the War Manpower Commission, estimated that the changes would increase the ratio of men drafted from one out of nine to one out of five. The commission's goal was to have nine million men in the armed forces by the end of 1943.[25] This facilitated the massive requirement of up to 200,000 men per month and would remain the standard for the length of the war. The World War II draft operated from 1940 until 1947 when its legislative authorization expired without further extension by Congress. During this time, more than 10 million men had been inducted into military service. With the expiration, no inductions occurred in 1947.[26] However, the SSS remained intact.

Opposition

Scattered opposition was encountered especially in the northern cities where African-Americans protested the system. The young Nation of Islam was at the forefront, with many Black Muslims jailed for refusing the draft, and their leader Elijah Muhammed was sentenced to federal prison for 5 years for inciting draft resistance. Organized draft resistance also developed in the Japanese American internment camps, where groups like the Heart Mountain Fair Play Committee refused to serve unless they and their families were released. 300 Nisei men from eight of the ten War Relocation Authority camps were arrested and stood trial for felony draft evasion; most were sentenced to federal prison.[27] American Communists also opposed the war until Germany attacked the Soviet Union in June 1941, whereupon they became supporters.

Conscientious objectors

Of the more than 72,000 men registering as conscientious objectors (CO), nearly 52,000 received CO status. Of these, over 25,000 entered the military in noncombatant roles, another 12,000 went to civilian work camps, and nearly 6,000 went to prison. Draft evasion only accounted for about 4% of the total inducted. About 373,000 alleged evaders were investigated with just over 16,000 being imprisoned.[28]

Cold War

The second peacetime draft began with passage of the Selective Service Act of 1948 after the STSA expired. The new law required all men, ages 18 to 26, to register. It also created the system for the "Doctor Draft" aimed at inducting health professionals into military service.[29] Unless otherwise exempted or deferred, these men could be called for up to 21 months of active duty and five years of reserve duty service. Congress further tweaked this act in 1950 although the post–World War II surplus of military manpower left little need for draft calls until Truman's declaration of national emergency in December 1950.[30] Only 20,348 men were inducted in 1948 and only 9,781 in 1949.

Between the Korean War's outbreak in June 1950 and the armistice agreement in 1953, Selective Service inducted over 1.5 million men.[26] Another 1.3 million volunteered, usually choosing the Navy or Air Force.[19][28] Congress passed the Universal Military Training and Service Act in 1951 to meet the demands of the war. It lowered the induction age to 18½ and extended active-duty service commitments to 24 months. Despite the early combat failures and later stalemate in Korea, the draft has been credited by some as playing a vital role in turning the tide of war.[19] A February 1953 Gallup Poll showed 70 percent of Americans surveyed felt the SSS handled the draft fairly. Notably, the demographic including all draft age men (males 21 to 29) reported 64 percent believed the draft to be fair.[31]

To increase equity in the system, President Dwight D. Eisenhower signed an executive order on July 11, 1953, that ended the paternity deferment for married men.[32] In large part, the change in the draft served the purposes of the burgeoning Cold War. From a program that had just barely passed Congressional muster during the fearful prelude to World War II, a more robust draft continued as fears now focused on the Soviet threat. Nevertheless, some dissenting voices in Congress continued to appeal to the history of voluntary American military service as preferable for a democracy.[33][34] The Korean War was the first time any form of student deferment was used. During the Korean War a student carrying at least twelve semester hours was spared until the end of his current semester.[35]

The United States breathed easier with the Korean War Armistice on July 27, 1953; however, technology brought new promises and threats. U.S. air and nuclear power fueled the Eisenhower doctrine of "massive retaliation". This strategy demanded more machines and fewer foot soldiers, so the draft slipped to the back burner. However, the head of the SSS, Maj. Gen. Hershey, urged caution fearing the conflict looming in Vietnam. In May 1953, he told his state directors to do everything possible to keep SSS alive in order to meet upcoming needs.[36]

Following the 1953 Korean War Armistice, Congress passed the Reserve Forces Act of 1955 with the aim of improving National Guard and federal Reserve Component readiness while also constraining its use by the president. Towards this end, it mandated a six-year service commitment, in a combination of reserve and active duty time, for every line military member regardless of their means of entry. Meanwhile, the SSS kept itself alive by devising and managing a complex system of deferments for a swelling pool of candidates during a period of shrinking requirements. The greatest challenge to the draft came not from protesters but rather lobbyists seeking additional deferments for their constituency groups such as scientists and farmers.[20]

Government leaders felt the potential for a draft was a critical element in maintaining a constant flow of volunteers. On numerous occasions Gen. Hershey told Congress for every man drafted, three or four more were scared into volunteering.[37] Assuming his assessment was accurate, this would mean over 11 million men volunteered for service because of the draft between January 1954 and April 1975.[19]

The policy of using the draft as a club to force "voluntary" enlistment was unique in U.S. history. Previous drafts had not aimed at encouraging individuals to sign up in order to gain preferential placement or less dangerous postings. However, the incremental buildup of Vietnam without a clear threat to the country bolstered this.[19] Some estimates suggest conscription encompassed almost one-third of all eligible men during the period of 1965–69.[38][39] This group represented those without exemption or resources to avoid military service. During the active combat phase, the possibility of avoiding combat by selecting their service and military specialty led as many as four out of 11 eligible men to enlist.[40][41] The military relied upon this draft-induced volunteerism to make its quotas, especially the Army, which accounted for nearly 95 percent of all inductees during Vietnam. For example, defense recruiting reports show 34% of the recruits in 1964 up to 50% in 1970 indicated they joined to avoid placement uncertainty via the draft.[42][43][44] These rates dwindled to 24% in 1972 and 15% in 1973 after the change to a lottery system. Accounting for other factors, it can be argued up to 60 percent of those who served throughout the Vietnam War did so directly or indirectly because of the draft.[40]

In addition, deferments provided an incentive for men to follow pursuits considered useful to the state. This process, known as channeling, helped push men into educational, occupational, and family choices they might not otherwise have pursued. Undergraduate degrees were valued. Graduate work had varying value over time, though technical and religious training received near constant support. War industry support in the form of teaching, research, or skilled labor also received deferred or exempt status. Finally, marriage and family were exempted because of its positive social consequences.[20][45] This included using presidential orders to extend exemptions again to fathers and others.[46] Channeling was also seen as a means of preempting the early loss of the country's "best and brightest" who had historically joined and died early in war.[47]

In the only extended period of military conscription of U.S. males during a major peacetime period, the draft continued on a more limited basis during the late 1950s and early 1960s. While a far smaller percentage of eligible males were conscripted compared to war periods, draftees by law served in the Army for two years. Elvis Presley and Willie Mays were two of the most famous people drafted during this period.

Public protests in the United States were few during the Korean War. However, the percentage of CO exemptions for inductees grew to 1.5% compared to a rate of just 0.5% in the past two wars. The Justice Department also investigated more than 80,000 draft evasion cases.[39][48][49]

Vietnam War

President Kennedy's decision to send military troops to Vietnam as "advisors" was a signal that Selective Service Director Lewis B. Hershey needed to visit the Oval Office. From that visit emerged two wishes of JFK with regard to conscription. The first was that the names of married men with children should occupy the very bottom of the callup list. Just above them should be the names of men who are married. This Presidential policy, however, was not to be formally encoded into Selective Service Status. Men who fit into these categories became known as Kennedy Husbands. When President Lyndon Johnson decided to rescind this Kennedy policy, there was a last-minute rush to the altar by thousands of American couples.

Many early rank-and-file anti-conscription protesters had been allied with the National Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy. The completion in 1963 of a Limited Nuclear Test Ban Treaty left a mass of undirected youth in search of a cause. Syndicated cartoonist Al Capp portrayed them as S.W.I.N.E, (Students Wildly Indignant About Nearly Everything). The catalyst for protest reconnection was the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin Resolution.

Consequently, there was some opposition to the draft even before the major U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War began. The large cohort of Baby Boomers who became eligible for military service during the Vietnam War was responsible for a steep increase in the number of exemptions and deferments, especially for college students. Besides being able to avoid the draft, college graduates who volunteered for military service (primarily as commissioned officers) had a much better chance of securing a preferential posting compared to less-educated inductees.

As U.S. troop strength in Vietnam increased, more young men were drafted for service there, and many of those still at home sought means of avoiding the draft. Since only 15,000 National Guard and Reserve soldiers were sent to Vietnam, enlistment in the Guard or the Reserves became a popular means of avoiding serving in a war zone. For those who could meet the more stringent enlistment standards, service in the Air Force, Navy, or Coast Guard was a means of reducing the chances of being killed. Vocations to the ministry and the rabbinate soared, because divinity students were exempt from the draft. Doctors and draft board members found themselves being pressured by relatives or family friends to exempt potential draftees.

The marriage deferment ended suddenly on August 26, 1965. Around 3:10pm President Johnson signed an order allowing the draft of men who married after midnight that day, then around 5pm he announced the change for the first time.[50]

Some conscientious objectors objected to the war based on the theory of Just War. One of these, Stephen Spiro, was convicted of avoiding the draft, but given a suspended sentence of five years. He was later pardoned by President Gerald Ford.[51]

There were 8,744,000 servicemembers between 1964 and 1975, of whom 3,403,000 were deployed to Southeast Asia.[52] From a pool of approximately 27 million, the draft raised 2,215,000 men for military service (in the United States, Vietnam, West Germany, and elsewhere) during the Vietnam era. The draft has also been credited with "encouraging" many of the 8.7 million "volunteers" to join rather than risk being drafted. The majority of servicemen deployed to Vietnam were volunteers.[53]

Of the nearly 16 million men not engaged in active military service, 57% were exempted (typically because of jobs including other military service), deferred (usually for educational reasons), or disqualified (usually for physical and mental deficiencies but also for criminal records including draft violations).[19] The requirements for obtaining and maintaining an educational deferment changed several times in the late 1960s. For several years, students were required to take an annual qualification test. In 1968, educational deferments were dropped for first year graduate students. Those further along in their graduate study could continue to receive a deferment. On December 1, 1969, a lottery was held to establish a draft priority for all those born between 1944 and 1950. Those with a high number no longer had to be concerned about the draft. Nearly 500,000 men were disqualified for criminal records, but less than 10,000 of them were convicted of draft violations.[28] Finally, as many as 100,000 draft eligible men fled the country.[54][55]

End of conscription

During the 1968 presidential election, Richard Nixon campaigned on a promise to end the draft.[56] He had first become interested in the idea of an all-volunteer army during his time out of office, based upon a paper by Martin Anderson of Columbia University.[57] Nixon also saw ending the draft as an effective way to undermine the anti-Vietnam war movement, since he believed affluent youths would stop protesting the war once their own probability of having to fight in it was gone.[58] There was opposition to the all-volunteer notion from both the Department of Defense and Congress, so Nixon took no immediate action towards ending the draft early in his presidency.[57]

Instead, the Gates Commission was formed, headed by Thomas S. Gates, Jr., a former Secretary of Defense in the Eisenhower administration. Gates initially opposed the all-volunteer army idea, but changed his mind during the course of the 15-member commission's work.[57] The Gates Commission issued its report in February 1970, describing how adequate military strength could be maintained without having conscription.[56][59] The existing draft law was expiring at the end of June 1971, but the Department of Defense and Nixon administration decided the draft needed to continue for at least some time.[59] In February 1971, the administration requested of Congress a two-year extension of the draft, to June 1973.[60][61]

Senatorial opponents of the war wanted to reduce this to a one-year extension, or eliminate the draft altogether, or tie the draft renewal to a timetable for troop withdrawal from Vietnam;[62] Senator Mike Gravel of Alaska took the most forceful approach, trying to filibuster the draft renewal legislation, shut down conscription, and directly force an end to the war.[63] Senators supporting Nixon's war efforts supported the bill, even though some had qualms about ending the draft.[61] After a prolonged battle in the Senate, in September 1971 cloture was achieved over the filibuster and the draft renewal bill was approved.[64] Meanwhile, military pay was increased as an incentive to attract volunteers, and television advertising for the U.S. Army began.[56] With the end of active U.S. ground participation in Vietnam, December 1972 saw the last men conscripted, who were born in 1952[65] and who reported for duty in June 1973. On February 2, 1972, a drawing was held to determine draft priority numbers for men born in 1953, but in early 1973 it was announced by Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird that no further draft orders would be issued.[66][67] In March 1973, 1974, and 1975, the Selective Service assigned draft priority numbers for all men born in 1954, 1955, and 1956, in case the draft was extended, but it never was.[68]

Command Sergeant Major Jeff Mellinger, believed to be the last drafted enlisted ranked soldier still on active duty, retired in 2011.[69]

Chief Warrant Officer 5 Ralph E. Rigby, the last Vietnam-era drafted soldier of Warrant Officer rank, retired from the army in November 10, 2014 after a 42-year career.[70]

Post-1980 draft registration

On July 2, 1980, President Carter issued Presidential Proclamation 4771 and re-instated the requirement that young men register with the Selective Service System.[71] At that time it was required that all males, born on or after January 1, 1960, register with the Selective Service System. Those now in this category are male U.S. citizens and male immigrant non-citizens between the ages of 18 and 25, who are required to register within 30 days of their 18th birthday.

The Selective Service System describes its mission as "to serve the emergency manpower needs of the Military by conscripting untrained manpower, or personnel with professional health care skills, if directed by Congress and the President in a national crisis".[72] Registration forms are available either online or at any U.S. Post Office.

The Selective Service registration form states that failure to register is a felony punishable by up to five years imprisonment or a $250,000 fine.[73] In practice, no one has been prosecuted for failure to comply with draft registration since 1986,[74] in part because prosecutions of draft resisters proved counter-productive for the government, and in part because of the difficulty of proving that noncompliance with the law was "knowing and willful". In interviews published in U.S. News & World Report in May 2016, current and former Selective Service System officials said that in 1988, the Department of Justice and Selective Service agreed to suspend any further prosecutions of nonregistrants.[75] Many people do not register at all, register late, or change addresses without notifying the Selective Service System.[76] Registration is a requirement for employment by the federal government and some states, as well as for receiving some state benefits such as driver's licenses.[77] Refusing to register can also cause a loss of eligibility for federal financial aid for college.[78]

Health care personnel

On December 1, 1989, Congress ordered the Selective Service System to put in place a system capable of drafting "persons qualified for practice or employment in a health care and professional occupation", if such a special-skills draft should be ordered by Congress.[79] In response, Selective Service published plans for the "Health Care Personnel Delivery System" (HCPDS) in 1989 and has had them ready ever since. The concept underwent a preliminary field exercise in Fiscal Year 1998, followed by a more extensive nationwide readiness exercise in Fiscal Year 1999. The HCPDS plans include women and men ages 20–54 in 57 different job categories.[80] As of May 2003, the Defense Department has said the most likely form of draft is a special skills draft, probably of health care workers.[81]

Legality

In 1918, the Supreme Court ruled that the World War I draft did not violate the United States Constitution in the Selective Draft Law Cases. The Court summarized the history of conscription in England and in colonial America, a history that it read as establishing that the Framers envisioned compulsory military service as a governmental power. It held that the Constitution's grant to Congress of the powers to declare war and to create standing armies included the power to mandate conscription. It rejected arguments based on states' rights, the 13th Amendment, and other provisions of the Constitution.

Later, during the Vietnam War, a lower appellate court also concluded that the draft was constitutional. United States v. Holmes, 387 F.2d 781 (7th Cir.), cert. denied, 391 U.S. 936 (1968).[82] Justice William O. Douglas, in voting to hear the appeal in Holmes, agreed that the government had the authority to employ conscription in wartime, but argued that the constitutionality of a draft in the absence of a declaration of war was an open question, which the Supreme Court should address.

During the World War I era, the Supreme Court allowed the government great latitude in suppressing criticism of the draft. Examples include Schenck v. United States, 249 U.S. 47 (1919)[83] and Gilbert v. Minnesota, 254 U.S. 325 (1920).[84] In subsequent decades, however, the Court has taken a much broader view of the extent to which advocacy speech is protected by the First Amendment. Thus, in 1971 the Court held it unconstitutional for a state to punish a man who entered a county courthouse wearing a jacket with the words "Fuck the Draft" visible on it. Cohen v. California, 403 U.S. 15 (1971).[85] Nevertheless, protesting the draft by the specific means of burning a draft registration card can be constitutionally prohibited, because of the government's interest in prohibiting the "nonspeech" element involved in destroying the card. United States v. O'Brien, 391 U.S. 367 (1968).[86]

Since the reinstatement of draft registration in 1980, the Supreme Court has heard and decided four cases related to the Military Selective Service Act: Rostker v. Goldberg, 453 U.S. 57 (1981), upholding the Constitutionality of requiring men but not women to register for the draft; Selective Service v. Minnesota Public Interest Research Group (MPIRG), 468 U.S. 841 (1984), upholding the Constitutionality of the first of the Federal "Solomon Amendment" laws, which requires applicants for Federal student aid to certify that they have complied with draft registration, either by having registered or by not being required to register; Wayte v. United States, 470 U.S. 598 (1985), upholding the policies and procedures which the Supreme Court thought the government had used to select the "most vocal" nonregistrants for prosecution, after the government refused to comply with discovery orders by the trial court to produce documents and witnesses related to the selection of nonregistrants for prosecution; and Elgin v. Department of the Treasury, 567 U.S. ____ (2012), regarding procedures for judicial review of denial of Federal employment for nonregistrants.[87]

In 1981, several men filed lawsuit in the case Rostker v. Goldberg, alleging that the Military Selective Service Act violates the Due Process Clause of the Fifth Amendment by requiring that men only and not also women register with the Selective Service System. The Supreme Court upheld the act, stating that Congress's "decision to exempt women was not the accidental byproduct of a traditional way of thinking about women", that "since women are excluded from combat service by statute or military policy, men and women are simply not similarly situated for purposes of a draft or registration for a draft, and Congress' decision to authorize the registration of only men therefore does not violate the Due Process Clause", and that "the argument for registering women was based on considerations of equity, but Congress was entitled, in the exercise of its constitutional powers, to focus on the question of military need, rather than 'equity.'"[88]

The Rostker v. Goldberg opinion's dependence upon deference on decision of the executive to exclude women from combat has garnered renewed scrutiny since the Department of Defense announced its decision in January 2013 to do away with most of the federal policies that have kept women from serving in combat roles in ground war situations. Both the U.S. Navy and the U.S. Air Force had by then already opened up virtually all positions in sea and air combat to women. At least two lawsuits have been filed challenging the continued Constitutionality of requiring men but not women to register with the Selective service System: National Coalition for Men v. Selective Service System (filed April 4, 2013, U.S. District Court for the Central District of California; dismissed by the District Court July 29, 2013 as not "ripe" for decision; appeal argued December 8, 2015 before the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals;[89] reversed and remanded February 19, 2016[90]), and Kyle v. Selective Service System (filed July 3, 2015, U.S. District Court for the District of New Jersey), brought on behalf of Elizabeth Kyle-LaBell, who tried to register but was turned away because she is female.[91]

Conscientious objection

According to the Selective Service System,[92]

- A conscientious objector is one who is opposed to serving in the armed forces and/or bearing arms on the grounds of moral or religious principles.

- [...]

- Beliefs which qualify a registrant for CO status may be religious in nature, but don't have to be. Beliefs may be moral or ethical; however, a man's reasons for not wanting to participate in a war must not be based on politics, expediency, or self-interest. In general, the man's lifestyle prior to making his claim must reflect his current claims.

The Supreme Court has ruled in cases United States v. Seeger[93] (1965) and Welsh v. United States[94] (1970) that conscientious objection can be by non-religious beliefs as well as religious beliefs; but it has also ruled in Gillette v. United States (1971) against objections to specific wars as grounds for conscientious objection.[95]

There is currently no mechanism to indicate that one is a conscientious objector in the Selective Service system. According to the SSS, after a person is drafted, he can claim Conscientious Objector status and then justify it before the Local Board. This is criticized because during the times of a draft, when the country is in emergency conditions, there could be increased pressure for Local Boards to be more harsh on conscientious objector claims.

There are two types of status for conscientious objectors. If a person objects only to combat but not to service in the military, then the person could be given noncombatant service in the military without training of weapons. If the person objects to all military service, then the person could be ordered to "alternative service" with a job "deemed to make a meaningful contribution to the maintenance of the national health, safety, and interest".

Selective Service reforms

The Selective Service System has maintained that they have implemented several reforms that would make the draft more fair and equitable.

Some of the measures they have implemented include:[96]

- Before and during the Vietnam War, a young man could get a deferment by showing that he was a full-time student making satisfactory progress towards a degree; now deferment only lasts to the end of the semester. If the man is a senior he can defer until the end of the academic year.

- The government has said that draft boards are now more representative of the local communities in areas such as race and national origin.

- A lottery system would be used to determine the order of people being called up. Previously the oldest men who were found eligible for the draft would be taken first. In the new system, the men called first would be those who are or will turn 20 years old in the calendar year or those whose deferments will end in the calendar year. Each year after, the man will be placed on a lower priority status until his liability ends.

Conscription controversies since 2003

The effort to enforce Selective Service registration law was abandoned in 1986. Since then, no attempt to reinstate conscription has been able to attract much support in the legislature or among the public.[76] Since early 2003, when the Iraq War appeared imminent, there have been attempts through legislation and campaign rhetoric to begin a new public conversation on the topic. Public opinion since 1973 has been largely negative, and the majority of proposals appear to be motivated by either concerns of fairness in who serves or of public officials withdrawing their support for a war for fear their children would have to serve in the line of fire.

In 2003, several Democratic congressmen (Charles Rangel of New York, Jim McDermott of Washington, John Conyers of Michigan, John Lewis of Georgia, Pete Stark of California, Neil Abercrombie of Hawaii) introduced legislation that would draft both men and women into either military or civilian government service, should there be a draft in the future. The Republican majority leadership suddenly considered the bill, nine months after its introduction, without a report from the Armed Services Committee (to which it had been referred), and just one month prior to the 2004 presidential and congressional elections. The Republican leadership used an expedited parliamentary procedure that would have required a two-thirds vote for passage of the bill. The bill was defeated on October 5, 2004, with two members voting for it and 402 members voting against.

In 2004, the platforms of both the Democratic and Republican parties opposed military conscription, but neither party moved to end draft registration. John Kerry in one debate criticized Bush's policies, "You've got stop-loss policies so people can't get out when they were supposed to. You've got a backdoor draft right now."

This statement was in reference to the U.S. Department of Defense use of "stop-loss" orders, which have extended the Active Duty periods of some military personnel. All enlistees, upon entering the service, volunteer for a minimum eight-year Military Service Obligation (MSO). This MSO is split between a minimum active duty period, followed by a reserve period where enlistees may be called back to active duty for the remainder of the eight years.[97] Some of these active duty extensions have been for as long as two years. The Pentagon stated that as of August 24, 2004, 20,000 soldiers, sailors, airmen, and Marines had been affected.[98] As of January 31, 2006 it has been reported that more than 50,000 soldiers and reservists had been affected.[99]

Despite arguments by defense leaders that they had no interest in re-instituting the draft, Representative Neil Abercrombie's (D-HI) inclusion of a DOD memo in the Congressional Record which detailed a meeting by senior leaders signaled renewed interest. Though the conclusion of the meeting memo did not call for a reinstatement of the draft, it did suggest Selective Service Act modifications to include registration by women and self-reporting of critical skills that could serve to meet military, homeland-defense, and humanitarian needs.[100] This hinted at more targeted draft options being considered, perhaps like that of the "Doctor Draft" that began in the 1950s to provide nearly 66% of the medical professionals who served in the Army in Korea.[101] Once created, this manpower tool continued to be used through 1972. The meeting memo gave DOD's primary reason for opposing a draft as a matter of cost effectiveness and efficiency. Draftees with less than two years' retention were said to be a net drain on military resources providing insufficient benefit to offset overhead costs of using them.[19]

Mentions of the draft during the presidential campaign led to a resurgence of anti-draft and draft resistance organizing.[102] One poll of young voters in October 2004 found that 29% would resist if drafted.[103]

In November 2006, Representative Charles B. Rangel (D-NY) again called for the draft to be reinstated; Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi rejected the proposal.[104]

On December 19, 2006, President George W. Bush announced that he was considering sending more troops to Iraq. The next day, the Selective Service System's director for operations and chief information officer, Scott Campbell, announced plans for a "readiness exercise" to test the system's operations in 2009, for the first time since 1998.[105]

On December 21, 2006, Veterans Affairs Secretary Jim Nicholson, when asked by a reporter whether the draft should be reinstated to make the military more equal, said, "I think that our society would benefit from that, yes sir." Nicholson proceeded to relate his experience as a company commander in an infantry unit which brought together soldiers of different socioeconomic backgrounds and education levels, noting that the draft "does bring people from all quarters of our society together in the common purpose of serving". Nicholson later issued a statement saying he does not support reinstating the draft.[106]

On August 10, 2007, with National Public Radio on "All Things Considered", Lieutenant General Douglas Lute, National Security Adviser to the President and Congress for all matters pertaining to the United States Military efforts in Iraq and Afghanistan, expressed support for a draft to alleviate the stress on the Army's all-volunteer force. He cited the fact that repeated deployments place much strain upon one soldier's family and himself which, in turn, can affect retention.[107]

A similar bill to Rangel's 2003 one was introduced in 2007, called the Universal National Service Act of 2007 (H.R. 393), but it has not received a hearing or been scheduled for consideration.

At the end of June 2014 in Pennsylvania 14,250 letters of conscription were erroneously posted to men born in the 19th century calling upon them to register for the US military draft. This was attributed to a clerk at the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation who failed to select a century during a transfer of 400,000 records to the Selective Service. The Selective Service identified 27,218 records of men born in the 19th century made errantly applicable by the change of century and began sending out notices to them on June 30.[108]

On June 14, 2016, the Senate voted to require women to register for the draft.[109]

Non-citizens

The Selective Service (and the draft) in the United States is not limited to citizens. Howard Stringer, for example, was drafted six weeks after arriving from his native Britain in 1965.[110][111] Today, non-citizen males of appropriate age in the United States, who are permanent residents (holders of green cards), seasonal agricultural workers not holding an H-2A Visa, refugees, parolees, asylees, and illegal immigrants, are required to register with the Selective Service System.[112] Refusal to do so is grounds for denial of a future citizenship application. In addition, immigrants who seek to naturalize as citizens must, as part of the Oath of Citizenship, swear to the following:

... that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the armed forces of the United States when required by the law; that I will perform work of national importance under civilian direction when required by the law;[113]

The United States Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) website also states however:

However, since 1975, USCIS has allowed the oath to be taken without the clauses: ". . .that I will bear arms on behalf of the United States when required by law; that I will perform noncombatant service in the Armed Forces of the United States when required by law...."

Non-citizens who serve in the United States military enjoy several naturalization benefits which are unavailable to non-citizens who do not, such as a waiver of application fees.[114] Permanent resident aliens who die while serving in the U.S. Armed Forces may be naturalized posthumously, which may be beneficial to surviving family members.[115]

See also

- Conscription crisis

- Demobilization of United States armed forces after World War II

- Draft lottery (1969)

- National service

- Peace Churches

- Selective Service System

- Service Nation

- Solomon Amendment

Footnotes

- ↑ Holbrook, Heber A. The Crisis Years: 1940 and 1941 Archived October 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine., The Pacific Ship and Shore Historical Review, July 4, 2001. p. 2. Archived October 19, 2012, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Who Must Register". sss.gov. Archived from the original on May 7, 2009. External link in

|publisher=(help) - ↑ John W. Chambers, II, ed. in chief, The Oxford Companion to American Military History (Oxford University Press, 1999, ISBN 0-19-507198-0), 180.

- ↑ Webster, Daniel (December 9, 1814) On Conscription, reprinted in Left and Right: A Journal of Libertarian Thought (Autumn 1965)

- ↑ Chambers, ed. The Oxford Companion to American Military History, 181.

- ↑ James W. Geary, We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (1991)

- ↑ Escott, Paul. Military Necessity: Civil-Military Relations in the Confederacy. Westport, CT: Praeger Security International, 2006.

- ↑ Arnold Shankman, "Draft Resistance in Civil War Pennsylvania." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1977): 190-204. online

- ↑ Moore 1924

- ↑ Howard Zinn, People's History of the United States. (Harper Collins, 2003): 134

- ↑ Chambers (1987)

- ↑ Zinn (2003)

- ↑ Nancy Ford, Americans all!: foreign-born soldiers in World War I (2001)

- ↑ Chambers, To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987) p 218

- 1 2 Shenk 2005, p. 62.

- ↑ Chambers, To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987) pp. 219–20

- ↑ John Whiteclay Chambers II, To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987) pp. 216–17

- ↑ Staff of the Catholic Peace Fellowship (2007). "The Life and Witness of Ben Salmon". Sign of Peace. 6.1 (Spring 2007).

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Morris, Brett. (2006). The Effects of the Draft on US Presidential Approval Ratings during the Vietnam War, 1954–1975, Doctoral dissertation, University of Alabama (Tuscaloosa).

- 1 2 3 4 Flynn, G. (1985). Lewis B. Hershey, Mr. Selective Service. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- ↑ "What the U.S.A. Thinks". Life. July 29, 1940. p. 20. Retrieved November 10, 2011.

- ↑ "Survey Shows What Youth is Thinking". Life. November 30, 1942. p. 110. Retrieved November 23, 2011.

- ↑ George Q. Flynn, The Draft, 1940–1973. (1993)

- ↑ Clifford, J., & Spencer, S. (1986). First Peacetime Draft. Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas.

- ↑ "Manpower: Sweeping Changes Halt Enlistments, Cut Top Draft Age to 38, Give McNutt Selective Service Control". Life. December 21, 1942. p. 27. Retrieved November 24, 2011.

- 1 2 Selective Service System. (May 27, 2003). Induction Statistics. In Inductions (by year) from World War I Through the End of the Draft (1973) Archived May 7, 2009, at the Wayback Machine.. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ↑ Muller, Eric L. "Draft resistance". Densho Encyclopedia. Retrieved August 27, 2014.

- 1 2 3 Chambers, J. (1987). To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America. New York: Free Press.

- ↑ Hershey, L. (1960). Outline of Historical Background of Selective Service and Chronology. (Available from Selective Service System, 1724 F Street NW, Washington, D.C. 20435)

- ↑ Selective Service System. (1953). Selective Service under the 1948 Act extended (212278-53-7). Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Gallup, G. (1972). The Gallup Poll: Public opinion, 1935–1971 (Vol. 2). New York: Random House.

- ↑ Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, Selective Service System. (February 19, 2004). Fast facts. In Effects of Marriage and Fatherhood on Draft Eligibility. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- ↑ Gilliam, R. (1982). The Peacetime Draft: Voluntarism to Coercion. In M. Anderson (Ed.), The Military Draft: Selected Readings on Conscription (pp. 97–116). Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press. (Original work published 1968)

- ↑ O'Sullivan, J. & A. Meckler. (Eds.). (1974). The Draft and Its Enemies: A Documentary History. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press.

- ↑ Myra MacPherson (2001). Long Time Passing, New Edition: Vietnam and the Haunted Generation. Bloomington, Indiana: Indiana University Press. p. 92.

- ↑ Hershey, 1953

- ↑ House Committee on Appropriations Hearings, 1958.

- ↑ Chambers, J. (ed), 1987

- 1 2 Flynn, G. (2000). The Draft, 1940–1973. Lawrence, KS: University of Kansas Press.

- 1 2 Useem, M. (1973). Conscription, Protest and Social Conflict: The Life and Death of a Draft Resistance Movement. New York: Wiley.

- ↑ Oi, W. (1982). "The Economic Cost of the Draft". In M. Anderson (Ed.), The Military Draft: Selected Readings on Conscription (pp. 317–346). Stanford, CA: Hoover Institution Press.

- ↑ Angrist, J. (1991). "The Draft Lottery and Voluntary Enlistment in the Vietnam Era". Journal of the American Statistical Association, 86(415), 584–95.

- ↑ Binkin, M., & Johnston, J. (1973), All-volunteer Armed Forces: Progress, Problems, and Prospects, report by the Brookings Institution prepared for the Senate Armed Services Committee, 93rd Congress, First Session. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office.

- ↑ Siu, Henry E. (2008). The fiscal role of conscription in the U.S. World War II effort. Journal of Monetary Economics, 55(6).

- ↑ Marmion, H. (1968). Selective Service: Conflict and Compromise. New York: John Wiley & Sons.

- ↑ Office of Public and Intergovernmental Affairs, 2004

- ↑ Senate Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, The nation's manpower revolution, 88th Cong., 2817 (1963) (testimony of Lewis B. Hershey).

- ↑ Chambers, 1987

- ↑ Kohn, S. (1986). Jailed for Peace: The History of American Draft Law Violations, 1658–1985. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press

- ↑ Orvedahl, Reid. "PrimeTime: Marrying to Avoid Draft". ABC News. ABC News. Retrieved June 6, 2015.

- ↑ Cornell, Tom (2008). "Stephen Spiro, 1940–2007". The Catholic Worker. LXXV (May–June): 6.

- ↑ U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs (Nov 2011). "America's Wars" (PDF). Retrieved June 7, 2012.

- ↑ Dunnigan, James F (1999). Dirty Little Secrets of the Vietnam War (First ed.). St martin's Press. p. 18. ISBN 0-312-19857-4.

- ↑ Chambers, J. (Ed.). (1999). The Oxford Companion to American Military History.

- ↑ Reeves, T. & Hess, K. (1970). The End of the Draft. New York: Random House.

- 1 2 3 Thomas W. Evans (Summer 1993). "The All-Volunteer Army After Twenty Years: Recruiting in the Modern Era". Sam Houston State University. Retrieved May 5, 2009.

- 1 2 3 Aitken, Jonathan (1996). Nixon: A Life. Regnery Publishing. ISBN 0-89526-720-9. pp. 396–397.

- ↑ Ambrose, Stephen (1989). Nixon, Volume Two: The Triumph of a Politician 1962–1972. Simon & Schuster. pp. 264–266.

- 1 2 Griffith, Robert K.; Robert K. Griffith, Jr., John Wyndham Mountcastle (1997). U.S. Army's Transition to the All-volunteer Force, 1868–1974. DIANE Publishing. ISBN 0-7881-7864-4. pp. 40–41.

- ↑ David E. Rosenbaum (February 3, 1971). "Stennis Favors 4-Year Draft Extension, but Laird Asks 2 Years". New York Times. Retrieved December 30, 2007.

- 1 2 Black, Conrad (2007). "Waging Peace". Richard M. Nixon: A Life in Full. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-519-9.

- ↑ David E. Rosenbaum (June 5, 1971). "Senators Reject Limits on Draft; 2-Year Plan Gains". New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ↑ John W. Finney (May 9, 1971). "Congress vs. President". New York Times. Retrieved December 31, 2007.

- ↑ David E. Rosenbaum (September 22, 1971). "Senate Approves Draft Bill, 55-30; President to Sign". New York Times. Retrieved December 29, 2007.

- ↑ "Selective Service System: History and Records". Sss.gov. Archived from the original on February 27, 2015. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Military draft system stopped". The Bulletin. Bend, Oregon. UPI. January 27, 1973. p. 1.

- ↑ "Military draft ended by Laird". The Times-News. Hendersonville, North Carolina. Associated Press. January 27, 1973. p. 1.

- ↑ "Selective Service System: History and Records". Sss.gov. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Set to retire, the last Army draftee 'loves being a soldier'". Boston Globe. Associated Press. July 4, 2011. Retrieved February 6, 2013.

- ↑ Phillips, Michael M. (November 18, 2014). "A Reluctant Soldier Completes His Duty". Wall Street Journal. Retrieved August 31, 2016.

- ↑ Proclamation 4771, Registration Under the Military Selective Service Act, July 2, 1980, 45 FR 45247, 94 Stat. 3775. Amended by Proclamation 7275, Registration Under the Military Selective Service Act, February 22, 2000, 65 FR 9199

- ↑ "Selective Service System". Sss.gov. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ Selective Service System: Fast Facts Archived July 27, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "What If I Choose Not To Register?". Retrieved July 27, 2008.

- ↑ Nelson, Steven (May 3, 2016). "Gender-Neutral Draft Registration Would Create Millions of Female Felons: It's unlikely any would face prison, but jailed draft resisters and former officials urge caution.". U.S. News & World Report. Retrieved May 15, 2016.

- 1 2 Edward Hasbrouck. "Prosecutions of Draft Registration Resisters". Resisters.info. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "State / Commonwealth and Territory Legislation". Selective Service System. Archived from the original on April 29, 2015.

- ↑ "Am I eligible to receive financial aid?". United States Department of Education.

- ↑ Edward Hasbrouck. "FAQ about Health Care Workers and the Draft". Medicaldraft.info. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ Proposed Health care personnel delivery System (HCPDS), 54 Federal Register, 33644-33654, August 15, 1989.

- ↑ Roger A. Lalich, Health care personnel delivery System: Another Doctor Draft? (Wisconsin Medical Journal, 2004). Archived July 2, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "''Holmes v. United States'', 391 U.S. 936 (1968)". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''Schenck v. United States'', 249 U.S. 47 (1919)". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''Gilbert v. Minnesota''". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''Cohen v. California'', 403 U.S. 15 (1971)". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''United States v. O'Brien'', 391 U.S. 367 (1968)". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Draft Registration, Draft Resistance, the Military Draft, and Health Care Workers and Women and the Draft". Resisters.info. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ↑ Rostker v. Goldberg, Cornell Law School, retrieved December 26, 2006.

- ↑ Hasbrouck, Edward. "Extend draft registration to women -- or end it?". The Practical Nomad. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ↑ Hasbrouck, Edward. "Future of Draft for Men and Women Goes to Court and Congress". WorldBeyondWar.org. Retrieved February 22, 2016.

- ↑ "Draft Registration, Draft Resistance, the Military Draft, and Health Care Workers and Women and the Draft". Resisters.info. Retrieved February 21, 2016.

- ↑ "Selective Service System: Fast Facts". Sss.gov. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''United States v. Seeger''". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. March 8, 1965. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''Welsh v. United States''". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "''Gillette v. United States''". Caselaw.lp.findlaw.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Differences Between The Selective Service Today And During Vietnam". sss.gov. Archived from the original on May 13, 2013. Retrieved May 1, 2013.

- ↑ "Directive 1304.25 Fulfilling the Military Service Obligation (MSO)". U.S. Department of Defense. August 25, 1997. Archived from the original on November 14, 2004.

- ↑ AlterNet / By Richard Muhammad (August 23, 2004). "War on Iraq: Firing Back". AlterNet. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ Stop-loss used to retain 50,000 troops | csmonitor.com Archived September 25, 2008, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Congressional Record. 108th Cong., 2d sess., 2004. Vol. 150, No. 130: E1938.

- ↑ Salyer, J. (April 26, 1954). "Training of medical officers". In Medical Science Publication 4, Recent Advances in Medicine and Surgery (19-30 April 1954): Based on Professional Medical Experiences in Japan and Korea 1950–1953 (chap.2). Retrieved May 5, 2009. Archived August 10, 2007, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Edward Hasbrouck. "Draft Registration, Draft Resistance, the Military Draft, and the Medical Draft in the USA". Resisters.info. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Newsweek Poll: Youth Vote Shows Bush, Kerry Neck-and-Neck (47% for Kerry, 45% for Bush); But Kerry's Lead Grows Among Likely Voters (52% to 42%)". Prnewswire.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Pelosi says no to draft legislation". CNN. November 20, 2006. Retrieved July 10, 2011.

- ↑ (December 22, 2006). "abc7.com: U.S. Testing National Draft Readiness 12/22/06". Abclocal.go.com. Retrieved October 28, 2013.

- ↑ "VA Head: Draft Beneficial to Society, Veterans Affairs Secretary Says Military Draft Beneficial, but He Doesn't Support It – CBS News". Archived from the original on May 15, 2008.

- ↑ Bush War Adviser Supports Considering a Military Draft FOXNews.com

- ↑ Y2K bug triggers army conscription notices sent to 14,000 dead men | Technology | The Guardian

- ↑ Steinhauer, Jennifer (June 14, 2016). "Senate Votes to Require Women to Register for the Draft". New York Times. Retrieved June 16, 2016.

- ↑ Grifiths, Katherine. "Sir Howard Stringer, U.S. Head Of Sony: Sony's knight buys Tinseltown dream." The Independent, September 18, 2004.

- ↑ "The Interview: Howard Stringer." The Independent, March 21, 2005. Archived August 5, 2010, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Selective Service System – Who Must Register

- ↑ USCIS Home Page

- ↑ Naturalization Information for Military Personnel USCIS Archived November 27, 2005, at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ The ABC's of Immigration: Military Service – March 29, 2005

References and further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Conscription. |

- Martin Anderson; Valerie Bloom (1976). Conscription: a select and annotated bibliography. Hoover Press. ISBN 978-0-8179-2571-0.. (Full text).

- Jehn, Christopher (2008). "Conscription". In David R. Henderson (ed.). Concise Encyclopedia of Economics (2nd ed.). Indianapolis: Library of Economics and Liberty. ISBN 978-0865976658. OCLC 237794267.

- Leach, Jack F. Conscription in the United States: Historical Background. (Rutland, Vt., 1952)

American Revolution

- Dougherty, Keith L. Collective Action under the Articles of Confederation. Cambridge U. Press, 2001. 211 pp.

Civil War

- Bernstein, Iver. The New York City Draft Riots: Their Significance for American Society and Politics in the Age of the Civil War (1990). online edition

- Cruz, Barbara C. and Jennifer Marques Patterson. "'In the Midst of Strange and Terrible Times': The New York City Draft Riots of 1863. Social Education. v. 69#1 2005. pp 10+, with teacher's guide and URL's. online version

- Geary, James W. We Need Men: The Union Draft in the Civil War (1991) pp. 264

- Geary, James W. "Civil War Conscription in the North: A Historiographical Review," Civil War History 32 (1986): 208–28, online

- Hilderman, Walter C., III. They Went into the Fight Cheering! Confederate Conscription in North Carolina. Boone, N.C.: Parkway, 2005. pp. 272

- Hyman, Harold M. A More Perfect Union: The Impact of the Civil War and Reconstruction on the Constitution. (1973), ch 13. online edition

- Kenny, Kevin. "Abraham Lincoln and the American Irish." American Journal of Irish Studies (2013): 39-64.

- Levine, Peter. "Draft Evasion in the North during the Civil War, 1863–1865," Journal of American History 67 (1981): 816–34 online edition

- Moore, Albert Burton. Conscription and Conflict in the Confederacy 1924 online edition

- Murdoch, Eugene C. One Million Men: The Civil War Draft in the North (1971).

- Shankman, Arnold. "Draft Resistance in Civil War Pennsylvania." Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography (1977): 190-204. online

- Wheeler, Kenneth H. "Local Autonomy and Civil War Draft Resistance: Holmes County, Ohio." Civil War History. v.45#2 1999. pp 147+ online edition

World War I

- Chambers II, John Whiteclay. To Raise an Army: The Draft Comes to Modern America (1987), comprehensive look at the national level.

- Ford, Nancy Gentile (2001). Americans All!: Foreign-born Soldiers in World War I. Texas A&M University Military History Series:73. ISBN 978-1-60344-132-2.

- Ford, Nancy Gentile. "'Mindful of the Traditions of His Race': Dual Identity and Foreign-born Soldiers in the First World War American Army." Journal of American Ethnic History 1997 16(2): 35–57. ISSN 0278-5927 Fulltext: in Ebsco

- Hickle, K. Walter. "'Justice and the Highest Kind of Equality Require Discrimination': Citizenship, Dependency, and Conscription in the South, 1917–1919." Journal of Southern History. v. 66#4 2000. pp 749+ online version

- Keith, Jeanette. "The Politics of Southern Draft Resistance, 1917–1918: Class, Race, and Conscription in the Rural South." Journal of American History 2000 87(4): 1335–1361. ISSN 0021-8723 Fulltext: in Jstor and Ebsco

- Keith, Jeanette. Rich Man's War, Poor Man's Fight: Race, Class, and Power in the Rural South during the First World War. 2004. 260pp.

- Kennedy, David M. Over Here: The First Worm War and American Society (1980), ch 3 online edition

- Shenk, Gerald E. "Race, Manhood, and Manpower: Mobilizing Rural Georgia for World War I," Georgia Historical Quarterly, 81 (Fall 1997), 622–62

- Woodward, C. Vann. Tom Watson, Agrarian Rebel (1938), pp 451–63.

- Sieger, Susan. "She Didn't Raise Her Boy to Be a Slacker: Motherhood, Conscription, and the Culture of the First World War." Feminist Studies. v.22#1 1996. pp 7+ online edition

- Shenk, Gerald E. (2005). "Work or fight!": Race, Gender, and the Draft in World War One. Macmillan Publishers. ISBN 978-1-4039-6175-4.

World War II

- Flynn, George Q. The Draft, 1940–1973. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993; the standard history

- Garry, Clifford J. and Samuel R. Spencer Jr. The First Peacetime Draft. 1986.

- Goossen, Rachel Waltner; Women against the Good War: Conscientious Objection and Gender on the American Home Front, 1941–1947 1997 online edition

- Westbrook, Robert. "'I Want a Girl Just Like the Girl That Married Harry James': American Women and the Problem of Political Obligation in WWII," American Quarterly 42 (December 1990): 587–614; online in JSTOR

Cold War and Vietnam

- Lawrence M. Baskir; William A. Strauss (1978). Chance and Circumstance: The Draft, the War, and the Vietnam Generation. Random House. ISBN 0-394-72749-5.

- Flynn, George Q. The Draft, 1940–1973. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas, 1993; the standard history

Recent

- Halstead, Fred. GIs Speak out against the War: The Case of the Ft. Jackson 8. 128 pages. New York: Pathfinder Press. 1970.

- Warner, John T. and Beth J. Asch. "The Record and Prospects of the All-volunteer Military in the United States." Journal of Economic Perspectives 2001 15(2): 169–192. ISSN 0895-3309 Fulltext: in Jstor and Ebsco

- Wooten; Evan M. "Banging on the Backdoor Draft: The Constitutional Validity of Stop-Loss in the Military," William and Mary Law Review, Vol. 47, 2005 online version

- Chambers II, John Whiteclay, ed. Draftees or Volunteers: A Documentary History of the Debate over Military Conscription in the United States, 1787–1973, (1975) (1976) (2011)

External links

| Look up conscription in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

- Selective Service System official website

- Resisters.info

- Rolling Stone Magazine: The Return of the Draft 2005

- How To Beat The Draft Board

- Reinstating the military draft by Walter E. Williams

- Are You Going to be Drafted? by Rod Powers. Discusses the improbability of the draft returning.