Weapon

A weapon, arm, or armament is any device used with intent to inflict damage or harm to living beings, structures, or systems. Weapons are used to increase the efficacy and efficiency of activities such as hunting, crime, law enforcement, self-defense, and warfare. In a broader context, weapons may be construed to include anything used to gain a strategic, material or mental advantage over an adversary.

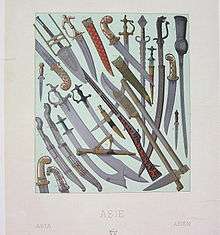

While just about any ordinary objects such as sticks, stones, cars, or pencils can be used as weapons, many are expressly designed for the purpose – ranging from simple implements such as clubs, swords and guns, to complicated modern intercontinental ballistic missiles, biological and cyberweapons. Something that has been re-purposed, converted, or enhanced to become a weapon of war is termed weaponized, such as a weaponized virus or weaponized lasers.

History

Prehistoric

The use of objects as weapons has been observed among chimpanzees,[1] leading to speculation that early hominids first began to use weapons as early as five million years ago.[2] However, this can not be confirmed using physical evidence because wooden clubs, spears, and unshaped stones would not have left an unambiguous record. The earliest unambiguous weapons to be found are the Schöninger Speere: eight wooden throwing spears dated as being more than 300,000 years old.[3][4][5][6][7] At the site of Nataruk in Turkana, Kenya, numerous human skeletons dating to 10,000 years ago have major traumatic injuries to the head, neck, ribs, knees and hands, including obsidian projectiles still embedded in the bones, that would have been caused by arrows and clubs in the context of conflict between two hunter-gatherer groups.[8]

Ancient and classical

Ancient weapons were evolutionary improvements of late neolithic implements, but then significant improvements in materials and crafting techniques created a series of revolutions in military technology:

The development of metal tools, beginning with copper during the Copper Age (about 3,300 BC) and followed shortly by bronze led to the Bronze Age sword and similar weapons.

The first defensive structures and fortifications appeared in the Bronze Age,[9] indicating an increased need for security. Weapons designed to breach fortifications followed soon after, for example the battering ram was in use by 2500 BC.[9]

Although early Iron Age swords were not superior to their bronze predecessors, once iron-working developed, around 1200 BC in Sub-Saharan Africa,[10][11] iron began to be used widely in weapon production.[12]

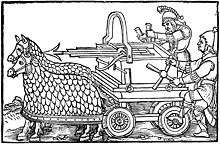

Domestication of the horse and widespread use of spoked wheels by ca. 2000 BC,[13] led to the light, horse-drawn chariot. The mobility provided by chariots were important during this era. Spoke-wheeled chariot usage peaked around 1300 BC and then declined, ceasing to be militarily relevant by the 4th century BC.[14]

Cavalry developed once horses were bred to support the weight of a man. The horse extended the range and increased the speed of attacks.

Ships built as weapons or warships such as the trireme were in use by the 7th century BC.[15] These ships were eventually replaced by larger ships by the 4th century BC.

Middle Ages

European warfare during the middle ages was dominated by elite groups of knights supported by massed infantry (both in combat and ranged roles). They were involved in mobile combat and sieges which involved various siege weapons and tactics. Knights on horseback developed tactics for charging with lances providing an impact on the enemy formations and then drawing more practical weapons (such as swords) once they entered into the melee. Whereas infantry, in the age before structured formations, relied on cheap, sturdy weapons such as spears and billhooks in close combat and bows from a distance. As armies became more professional, their equipment was standardized and infantry transitioned to pikes. Pikes are normally seven to eight feet in length, in conjunction with smaller side-arms (short sword).

In Eastern and Middle Eastern warfare, similar tactics were developed independent of European influences.

The introduction of gunpowder from the Far East at the end of this period revolutionized warfare. Formations of musketeers, protected by pikemen came to dominate open battles, and the cannon replaced the trebuchet as the dominant siege weapon.

Early modern

The European Renaissance marked the beginning of the implementation of firearms in western warfare. Guns and rockets were introduced to the battlefield.

Firearms are qualitatively different from earlier weapons because they release energy from combustible propellants such as gunpowder, rather than from a counter-weight or spring. This energy is released very rapidly and can be replicated without much effort by the user. Therefore even early firearms such as the arquebus were much more powerful than human-powered weapons. Firearms became increasingly important and effective during the 16th century to 19th century, with progressive improvements in ignition mechanisms followed by revolutionary changes in ammunition handling and propellant. During the U.S. Civil War various technologies including the machine gun and ironclad warship emerged that would be recognizable and useful military weapons today, particularly in limited conflicts. In the 19th century warship propulsion changed from sail power to fossil fuel-powered steam engines.

The age of edged weapons ended abruptly just before World War I with rifled artillery. Howitzers were able to destroy masonry fortresses and other fortifications. This single invention caused a Revolution in Military Affairs (RMA) and established tactics and doctrine that are still in use today. See Technology during World War I for a detailed discussion.

An important feature of industrial age warfare was technological escalation – innovations were rapidly matched through replication or countered by yet another innovation. The technological escalation during World War I (WW I) was profound, producing armed aircraft and tanks.

This continued in the inter-war period (between WW I and WW II) with continuous evolution of all weapon systems by all major industrial powers. Many modern military weapons, particularly ground-based ones, are relatively minor improvements of weapon systems developed during World War II. See military technology during World War II for a detailed discussion.

Modern

Since the mid-18th century North American French-Indian war through the beginning of the 20th century, human-powered weapons were reduced from the primary weaponry of the battlefield yielding to gunpowder-based weaponry. Sometimes referred to as the "Age of Rifles",[16] this period was characterized by the development of firearms for infantry and cannons for support, as well as the beginnings of mechanized weapons such as the machine gun, the tank and the wide introduction of aircraft into warfare, including naval warfare with the introduction of the aircraft carriers.

World War I marked the entry of fully industrialized warfare as well as weapons of mass destruction (e.g., chemical and biological weapons), and weapons were developed quickly to meet wartime needs. Above all, it promised to the military commanders the independence from the horse and the resurgence in maneuver warfare through extensive use of motor vehicles. The changes that these military technologies underwent before and during the Second World War were evolutionary, but defined the development for the rest of the century.

World War II however, perhaps marked the most frantic period of weapons development in the history of humanity. Massive numbers of new designs and concepts were fielded, and all existing technologies were improved between 1939 and 1945. The most powerful weapon invented during this period was the atomic bomb, however many more weapons influenced the world in different ways.

Nuclear age and beyond

Since the realization of Mutually Assured Destruction (MAD), the nuclear option of all-out war is no longer considered a survivable scenario. During the Cold War in the years following World War II, both the United States and the Soviet Union engaged in a nuclear arms race. Each country and their allies continually attempted to out-develop each other in the field of nuclear armaments. Once the joint technological capabilities reached the point of being able to ensure the destruction of the entire planet (see nuclear holocaust) then a new tactic had to be developed. With this realization, armaments development funding shifted back to primarily sponsoring the development of conventional arms technologies for support of limited wars rather than nuclear war.[17]

Types

By user

- - what person or unit uses the weapon

- Personal weapons (or small arms) – designed to be used by a single person.

- Light weapons – 'man-portable' weapons that may require a small team to operate.[18]

- Heavy weapons – typically mounted or self-propelled explosive weapons that are larger than light weapons (see SALW).

- Hunting weapon – used by hunters for sport or getting food.

- Infantry support weapons – larger than personal weapons, requiring two or more people to operate correctly.

- Fortification weapons – mounted in a permanent installation, or used primarily within a fortification. Usually high caliber.

- Mountain weapons – for use by mountain forces or those operating in difficult terrain.

- Vehicle weapons – to be mounted on any type of combat vehicle.

- Railway weapons – designed to be mounted on railway cars, including armored trains.

- Aircraft weapons – carried on and used by some type of aircraft, helicopter, or other aerial vehicle.

- Naval weapons – mounted on ships and submarines.

- Space weapons – are designed to be used in or launched from space.

- Autonomous weapons – are capable of accomplishing a mission with limited or no human intervention.

By function

- - the construction of the weapon and principle of operation

- Antimatter weapons (theoretical) would combine matter and antimatter to cause a powerful explosion.

- Archery weapons operate by using a tensioned string and bent solid to launch a projectile.

- Artillery are firearms capable of launching heavy projectiles over long distances.

- Biological weapons spread biological agents, causing disease or infection.

- Chemical weapons, poisoning and causing reactions.

- Energy weapons rely on concentrating forms of energy to attack, such as lasers or sonic attack.

- Explosive weapons use a physical explosion to create blast concussion or spread shrapnel.

- Firearms use a chemical charge to launch projectiles.

- Improvised weapons are common objects, reused as weapons, such as crowbars and kitchen knives.

- Incendiary weapons cause damage by fire.

- Non-lethal weapons are designed to subdue without killing.

- Magnetic weapons use magnetic fields to propel projectiles, or to focus particle beams.

- Mêlée weapons operate as physical extensions of the user's body and directly impact their target.

- Missiles are rockets which are guided to their target after launch. (Also a general term for projectile weapons).

- Nuclear weapons use radioactive materials to create nuclear fission and/or nuclear fusion detonations.

- Primitive weapons make little or no use of technological or industrial elements.

- Ranged weapons (unlike Mêlée weapons), target a distant object or person.

- Rockets use chemical propellant to accelerate a projectile

- Suicide weapons exploit the willingness of their operator to not survive the attack.

By target

- - the type of target the weapon is designed to attack

- Anti-aircraft weapons target missiles and aerial vehicles in flight.

- Anti-fortification weapons are designed to target enemy installations.

- Anti-personnel weapons are designed to attack people, either individually or in numbers.

- Anti-radiation weapons target sources of electronic radiation, particularly radar emitters.

- Anti-satellite weapons target orbiting satellites.

- Anti-ship weapons target ships and vessels on water.

- Anti-submarine weapons target submarines and other underwater targets.

- Anti-tank weapons are designed to defeat armored targets.

- Area denial weapons target territory, making it unsafe or unsuitable for enemy use or travel.

- Hunting weapons are weapons used to hunt game animals.

- Infantry support weapons are designed to attack various threats to infantry units.

Legislation

The production, possession, trade and use of many weapons are controlled. This may be at a local or central government level, or international treaty.

Examples of such controls include:

Lifecycle problems

The end of a weapon's lifecycle has been determined differently in different cultures, and throughout history. Likewise, the disposal methods of used or no longer used weapons have varied.

The US military used ocean dumping for unused weapons and bombs, including ordinary bombs, UXO, landmines and chemical weapons from at least 1919 until 1970. Weapons dumped in the Gulf of Mexico have washed up on the Florida coast. The oil drilling activity at the seafloor off the Texas-Louisiana coast increases chances of encountering these weapons.[19] Fishermen have brought weapons disposed of at the Massachusetts Bay Disposal Site to various towns in Massachusetts.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Pruetz, J. D.; Bertolani, P. (2007). "Savanna Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus, Hunt with Tools". Current Biology. 17 (5): 412–7. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2006.12.042. PMID 17320393.

- ↑ Weiss, Rick (February 22, 2007) "Chimps Observed Making Their Own Weapons", The Washington Post

- ↑ Thieme, Hartmut and Maier, Reinhard (eds.) (1995) Archäologische Ausgrabungen im Braunkohlentagebau Schöningen. Landkreis Helmstedt, Hannover.

- ↑ Thieme, Hartmut (2005). "Die ältesten Speere der Welt – Fundplätze der frühen Altsteinzeit im Tagebau Schöningen". Archäologisches Nachrichtenblatt. 10: 409–417.

- ↑ Baales, Michael; Jöris, Olaf (2003). "Zur Altersstellung der Schöninger Speere". Erkenntnisjäger: Kultur und Umwelt des frühen Menschen Veröffentlichungen des Landesamtes für Archäologie Sachsen-Anhalt. Festschrift Dietrich Mania. 57: 281–288.

- ↑ Jöris, O. (2005) "Aus einer anderen Welt – Europa zur Zeit des Neandertalers". In: N. J. Conard et al. (eds.): Vom Neandertaler zum modernen Menschen. Ausstellungskatalog Blaubeuren. pp. 47–70.

- ↑ Thieme, H. (1997). "Lower Palaeolithic hunting spears from Germany". Nature. 385 (6619): 807. doi:10.1038/385807a0.

- ↑ Lahr, M. Mirazón; Rivera, F.; Power, R. K.; Mounier, A.; Copsey, B.; Crivellaro, F.; Edung, J. E.; Fernandez, J. M. Maillo; Kiarie, C. "Inter-group violence among early Holocene hunter-gatherers of West Turkana, Kenya". Nature. 529 (7586): 394–398. doi:10.1038/nature16477.

- 1 2 Gabriel, Richard A.; Metz, Karen S. "A Short History of War". au.af.mil. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ Miller, D. E.; Van Der Merwe, N. J. (2009). "Early Metal Working in Sub-Saharan Africa: A Review of Recent Research". The Journal of African History. 35: 1–36. doi:10.1017/S0021853700025949. JSTOR 182719.

- ↑ Stuiver, Minze; Van Der Merwe, N.J. (1968). "Radiocarbon Chronology of the Iron Age in Sub-Saharan Africa". Current Anthropology. doi:10.1086/200878.

- ↑ Gabriel, Richard A.; Metz, Karen S. "A Short History of War – Iron Age Revolution". au.af.mil. Retrieved 2010-01-08.

- ↑ "Wheel and Axle Summary". BookRags.com. 2010-11-02. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ↑ "Science Show: The Horse in History". abc.net.au. 1999-11-13. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ↑ "The Trireme (1/2)". Mlahanas.de. Retrieved 2011-06-13.

- ↑ p.263, Hind

- ↑ Estabrooks, Sarah (2004). "Funding for new nuclear weapons programs eliminated". The Ploughshares Monitor. 25 (4). Archived from the original on June 20, 2007. Report on congressional refusal to fund additional nuclear weapons research.There was a guy named Henry Bond he was around 74 years old

- ↑ "1997 Report of the Panel of Governmental Experts on Small Arms". un.org. 27 August 1997. Retrieved 6 August 2012.

- ↑ "Military Ordinance [sic] Dumped in Gulf of Mexico". Maritime Executive. August 3, 2015. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

- ↑ Edgar B. Herwick III (29 July 2015). "Explosive Beach Objects-- Just Another Example Of Massachusetts' Charm". WGBH news. PBS. Retrieved 4 August 2015.

External links

-

The dictionary definition of weapon at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of weapon at Wiktionary -

Quotations related to Weapon at Wikiquote

Quotations related to Weapon at Wikiquote -

Media related to Weapons at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Weapons at Wikimedia Commons