Romulus

| Romulus | |

|---|---|

_-_n._8226_-_Certosa_di_Pavia_-_Medaglione_sullo_zoccolo_della_facciata.jpg) Romulus and his brother Remus from a 15th century frieze, Certosa di Pavia | |

| King of Rome | |

| Reign | c.753-c.717 BC |

| Predecessor | None |

| Successor | Numa Pompilius |

| Mother | Rhea (or Ilia) Sylvia |

|

| This article is part of a series on the politics and government of Ancient Rome |

| Periods |

|

| Roman Constitution |

| Ordinary magistrates |

| Extraordinary magistrates |

| Titles and honours |

| Precedent and law |

|

|

| Assemblies |

| Religion in ancient Rome |

|---|

|

| Practices and beliefs |

| Priesthoods |

| Deities |

|

| Related topics |

Romulus was the founder and first king of Rome. The legend attributes to him the establishment of many of Rome's fundamental religious, legal, political, and social institutions. The myth of the city's founding and his reign follows the events told in the legend of Romulus and his twin brother Remus, whose death occurred prior to the foundation of the city.

Overview

Romulus was born in Alba Longa, He and his twin brother Remus were abandoned in the wild at the order of their maternal uncle Amulius, after the usurpation of their grandfather Numitor's throne. They survived and were adopted by shepherds. As adults, they deposed Amulius and restored their grandfather to the throne. With a group of Alban colonists in tow, they set out to found a city of their own. They chose the area where they had grown up, the future site of Rome. A conflict over the hill on which to build led to the death of Remus.

Establishment of the city

The first act by Romulus was to conduct appropriate religious rites. He then laid out the city's boundaries with a trench dug with a plough. He fortified the city, and then called his new community together to form the new city's government. After he issued a public address that had been prepared for the occasion with help from Numitor, the people gave their universal support to the foundation of a kingdom under his rule. After receiving good augurs, he accepted the crown and became the first King of Rome.

He divided the city into thirds (tribes) and each of them (along with the city's land) into 10 sub-units (Curiae). He then identified the wealthy, well-born, and virtuous and with them created the city's nobility, the Patricians. The commoners composed the Plebeian class. He assigned each duties and rights under a system of patronage to help ensure community cohesion. He created the Senate out of the 100 most prominent men and laid out the method of law-making and ruling. He established the royal guard and attendants. He laid out the city's official religion, its practices, deities, and the offices of those charged with maintaining its traditions and conducting its rites.

The rape of the Sabine women and the aftermath

Romulus next turned to the city's growth. He outlawed infanticide and established the Asylum, where any emigre could claim protection if they were seeking Roman citizenship. The latter encouraged growth, but resulted in an imbalance of men and women. The city appealed to its neighbors to provide brides, but they were rebuffed. In response, Romulus announced a momentous festival and games and invited the people of the neighboring cities to attend. Many did from all around. The Sabines, in particular, came in droves. At a prearranged signal, the Romans began to snatch and carry off the marriageable women among their guests. This led to wars with their neighbors, in which Rome handily defeated, in turn, the armies of Caenina, Crustumerium, and Antemnae. It annexed their lands and cities. Romulus pledged a temple to Jupiter after defeating the armies of Caenina, and slaying its king himself.

These victories prompted the Sabines, under the leadership of Titus Tatius to invade Rome. With the assistance of Tarpeia, the daughter of the commander, the Sabines gained control over the Roman citadel. What followed was an epic battle between the two armies. The Battle of the Lacus Curtius featured the advance and retreat of both armies, and heroism on both sides. At a critical turning point during the battle, Romulus pledged a temple to Jupiter Stator (Jupiter Standing firm) and rallied the broken Roman lines, avoiding catastrophe.

Union with the Sabines and the death of Tatius

Ultimately, the conflict was ended when the women abductees intervened and convinced the two cities to make peace. They came together as a single kingdom. Romulus and Tatius became joint kings and the two peoples were merged with their capitol in Rome. They ruled jointly for several years. During their co-rule, they conquered the city of Carmania. Tatius was killed over a dispute involving the people of Laurentium.

Romulus' later rule and death

Romulus continued to rule as the sole sovereign. After aggression by the king of Fidenae, Rome defeated their army and conquered their city. The Etruscan city of Veii was likewise subdued.

Romulus vanished under mysterious circumstances and was never seen again. Some believed that he had been murdered by nobles and that his body had been secretly dismembered and buried by them on their estates. He was deified and worshiped as Quirinus. Numa Pompilius succeeded him as Rome's second king.

Modern scholarship

The legend as a whole encapsulates Rome's ideas of itself, its origins and moral values. For modern scholarship, it remains one of the most complex and problematic of all foundation myths. Ancient historians had no doubt that Romulus gave his name to the city. Most modern historians believe his name is a back-formation from the name of the city. Roman historians dated the city's foundation to between 758 and 728 BC, and Plutarch reckoned the Romulus' and his twins' birth year as 771 BC. A tradition that gave Romulus a distant ancestor in the semi-divine Trojan prince Aeneas was further embellished, and Romulus was made the direct ancestor of Rome's first Imperial dynasty. It's unclear whether or not the tale of Romulus or that of the twins are original elements of the foundation myth or whether both or either were added.

Romulus-Quirinus

Ennius (fl. 180s BC) refers to Romulus as a divinity in his own right, without reference to Quirinus. Roman mythographers identified the latter as an originally Sabine war-deity, and thus to be identified with Roman Mars. Lucilius lists Quirinus and Romulus as separate deities, and Varro accords them different temples. Images of Quirinus showed him as a bearded warrior wielding a spear as a god of war, the embodiment of Roman strength and a deified likeness of the city of Rome. He had a Flamen Maior called the Flamen Quirinalis, who oversaw his worship and rituals in the ordainment of Roman religion attributed to Romulus's royal successor, Numa Pompilius. There is however no evidence for the conflated Romulus-Quirinus before the 1st century BC.[1][2]

Ovid in Book 14, lines 812-828, of the Metamorphoses gives a description of the deification of Romulus and his wife Hersilia, who are given the new names of Quirinus and Hora respectively. Mars, the father of Romulus, is given permission by Jupiter to bring his son up to Olympus to live with the Olympians.

One theory of this tradition concerns the emergence of two mythical figures from a single, earlier legend. Romulus is a founding hero, Quirinus may have been a god of the harvest, and the Fornacalia was a festival celebrating a staple crop (spelt). Through the traditional dates from the tales and the festivals, they are each associated with one another. A legend of the murder of such a founding hero, the burying of the hero's body in the fields (found in some accounts), and a festival associated with that hero, a god of the harvest, and a food staple is a pattern recognized by anthropologists. Called a "dema archetype", this pattern suggests that in a prior tradition, the god and the hero were in fact the same figure and later evolved into two.[3]

Historicity

Possible historical bases for the broad mythological narrative remain unclear and disputed.[4]

Modern scholarship approaches the various known stories of the myth as cumulative elaborations and later interpretations of Roman foundation-myth. Particular versions and collations were presented by Roman historians as authoritative, an official history trimmed of contradictions and untidy variants to justify contemporary developments, genealogies and actions in relation to Roman morality. Other narratives appear to represent popular or folkloric tradition; some of these remain inscrutable in purpose and meaning. Wiseman sums the whole as the mythography of an unusually problematic foundation and early history.[5][6]

The unsavoury elements of many of the myths concerning Romulus have led some scholars to describe them as "shameful" or "disreputable".[7] In antiquity such stories became part of anti-Roman and anti-pagan propaganda. More recently, the historian Hermann Strasburger postulated that these were never part of authentic Roman tradition, but were invented and popularized by Rome's enemies, probably in Magna Graecia, during the latter part of the fourth century BC.[7] This hypothesis is rejected by other scholars, such as Tim Cornell, who notes that by this period, the story of Romulus and Remus had already assumed its standard form, and was widely accepted at Rome. Other elements of the Romulus mythos clearly resemble common elements of folk tale and legend, and thus strong evidence that the stories were both old and indigenous.[7] Likewise, Momigliano finds Strasburger's argument well-developed, but entirely implausible; if the Romulus myths were an exercise in mockery, they were a signal failure.[6]

Depictions in art

The episodes which make up the legend, most significantly that of the rape of the Sabine women, the tale of Tarpeia, and the death of Tatius have been a significant part of ancient Roman scholarship and the frequent subject of art, literature and philosophy since ancient times.

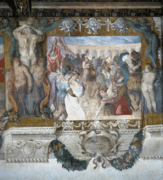

Palazzo Magnani

In the late 16th century, the wealthy Magnani family from Bologna commissioned a series of artworks based on the Roman foundation myth. The artists contributing works included a sculpture of Hercules with the infant twins by Gabriele Fiorini, featuring the patron's own face. The most important works were an elaborate series of frescoes collectively known as Histories of the Foundation of Rome by the Brothers Carracci: Ludovico, Annibale, and Agostino.

-

Romulus marking the city's boundaries with a plough

-

The Asylum (Inter duos Lucos)

-

The rape of the Sabine women

-

Romulus dedicating the temple to Jupiter Feretrius

-

the Battle of the Lacus Curtius

-

The death of Titus Tatius in Laurentium

-

Romulus appearing to Proculus Julius

-

The Pride of Romulus

The rape of the Sabine women

-

Ratto delle Sabine "The Rape of the Sabines", Il Sodoma (1507)

-

L'Enlèvement des Sabines "The Abduction of the Sabines", Nicolas Poussin (1638)

-

The Rape of the Sabine Women, Peter Paul Rubens (1634–36)

-

_2_2013_February.jpg)

Ratto delle Sabine "Rape of the Sabines", Giambologna (1583)

-

Ratto delle Sabine "The Rape of the Sabines", Jacopo Ligozzi (c.1565-1627)

-

_Rape_of_the_Sabine_Women.jpg)

L'Enlèvement des Sabines "The Abduction of the Sabines", Attributed to Theodoor van Thulden (17th c.)

-

"The Rape of the Sabine Women", Sebastiano Ricci (c.1700)

-

Der Raub der Sabinerinnen "The Rape of the Sabine Women", Johann Heinrich Schönfeld (1640)

-

The Rape Of The Sabines - The Abduction, Charles Christian Nahl (1870)

-

The Rape Of The Sabines - The Captivity, Charles Christian Nahl (1871)

-

The Rape Of The Sabines - The Invasion, Charles Christian Nahl (1871)

Tarpeia

-

The Vestal Virgin Tarpeia Beaten by Tatius’ soldiers Il Sodoma (16th c.)

-

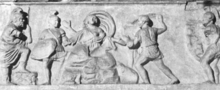

Tarpeia's punishment, Pentelic marble fragment from the Frieze of the Basilica Aemilia (100 BC-100 AD

-

Reconstruction of Basilica Aemilia Frieze marble fragment

-

_(14751427905).jpg)

Tarpeia, Illustration from Pictura loquens "the Heroic Accounts of Hadrian Schoonebeeck" (1695) (14751427905)

-

Tarpeia conspires with Tatius in an illustration from The story of the Romans by Hélène Adeline Guerber (1896)

Hersilia

-

Print from Romolo ed Ersilia, final scene, Act 3, Artist;: Giovanni Battista Cipriani, Engraver: Francesco Bartolozzi (1781)

-

Hersilia from a detail of L'Intervention des Sabines "The Intervention of the Sabine Women", Jacques-Louis David (1799)

-

Ersilia separa Romolo da Tazio "Hersilia Separating Romulus and Tatius, Guercino (1645)

Death of Tatius[8]

| La mort de Tatius "The Death of Tatius", Étienne-Barthélémy Garnier (1788) |

La mort de Tatius "The Death of Tatius", Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (1788) |

La mort de Tatius "The Death of Tatius", Jacques Réattu (1788) |

Death of Romulus

"Apparition of Romulus before Proculus", Rubens (17th c.) |

See also

Notes

- ↑ Evans, 103 and footnote 66: citing quotation of Ennius in Cicero, 1.41.64.

- ↑ Fishwick, Duncan (1993), The Imperial Cult in the Latin West (2nd ed.), Leiden: Brill, p. 53, ISBN 90-04-07179-2.

- ↑ Angelo Brelich Quirinus: una divinita' romana alla luce della comparazione storica "Studi e Materiali di Storia delle religioni" 1960.

- ↑ The archaeologist Andrea Carandini is one of very few modern scholars who accept Romulus and Remus as historical figures, based on the 1988 discovery of an ancient wall on the north slope of the Palatine Hill in Rome. Carandini dates the structure to the mid-8th century BC and names it the Murus Romuli. See Carandini, La nascita di Roma. Dèi, lari, eroi e uomini all'alba di una civiltà (Torino: Einaudi, 1997) and Carandini. Remo e Romolo. Dai rioni dei Quiriti alla città dei Romani (775/750 - 700/675 a. C. circa) (Torino: Einaudi, 2006)

- ↑ Wiseman, TP (1995), Remus, A Roman myth, Cambridge University Press

- 1 2 Momigliano, Arnoldo (2007), "An interim report on the origins of Rome", Terzo contributo alla storia degli studi classici e del mondo antico, 1, Rome, IT: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, pp. 545–98 A critical, chronological review of historiography related to Rome's origins.

- 1 2 3 Cornell, pp. 60–62.

- ↑ the subject for the 1788 Prix de Rome was "the death of Tatius". These three were all award winners.

Bibliogrophy

- Cornell, T. (1995), The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-75495-1

- Tennant, PMW (1988). "The Lupercalia and the Romulus and Remus Legend" (PDF). Acta Classica. XXXI: 81–93. ISSN 0065-1141. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Wiseman, T.P. (1983). "The Wife and Children of Romulus". The Classical Quarterly. Cambridge University Press. XXXI (ii): 445–452. Retrieved 26 November 2016.

| Legendary titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| New creation | King of Rome 753–717 |

Succeeded by Numa Pompilius |

| Preceded by Numitor |

King of Alba Longa | |