Romulus and Remus

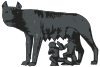

In Roman mythology, Romulus and Remus are legendary twin brothers, whose story tells the events that led to the founding of the city of Rome and the Roman Kingdom by Romulus. The tale of the death of Remus at the hands of his brother and others has been a major source of inspiration for artists throughout the ages. Since ancient times, the image of the twins being suckled by a she-wolf has been a symbol of the city of Rome and the Roman people. Although the tale takes place before the founding of Rome around 750 BC, the earliest known written account of the myth is from the late 3rd century BC. Whether the twins' myth was an original part of Roman myth or a later development is a subject of ongoing debate.

The myth begins with the story of their origins and the palace intrigue that resulted in their being left to die in the wilderness.

Romulus and Remus were born in Alba Longa, one of the ancient Latin cities near the future site of Rome. Their mother, Rhea Silvia was a vestal virgin and the daughter of the former king, Numitor, who had been displaced by his brother Amulius. In some sources, Rhea Silvia conceived them when their father, the god Mars visited her in a sacred grove dedicated to him.[2] Through their mother, the twins were descended from Greek and Latin nobility.

Seeing them as a possible threat to his rule, King Amulius ordered them to be killed and they were abandoned on the bank of the Tiber River to die. They were saved by the god Tiberinus, Father of the River and survived with the care of others, at the site of what would eventually become Rome. In the most well-known episode, the twins were suckled by a she-wolf, in a cave now known as the Lupercal.[3] Eventually, they were adopted by Faustulus, a shepherd. They grew up tending flocks, unaware of their true identities. Over time, their natural-born leadership abilities attracted a company of supporters from the community.

When they were young adults, they became involved in a dispute between supporters of Numitor and Amulius. As a result, Remus was taken prisoner and brought to Alba Longa. Both his grandfather and the king suspected his true identity. Romulus, meanwhile, had organized an effort to free his brother and set out with help for the city. During this time they learned of their past and joined forces with their grandfather to restore him to the throne. Amulius was killed and Numitor was reinstated as king of Alba. The twins set out to build a city of their own.

After arriving back in the area of the seven hills, they disagreed about the hill upon which to build. Romulus prefered the Palatine Hill, above the Lupercal; Remus preferred the Aventine hill. When they could not resolve the dispute, they agreed to seek the gods' approval through a contest of augury. Remus first saw 6 auspicious birds but soon after, Romulus saw 12, and claimed to have won divine approval. This new dispute furthered the contention between them. In the aftermath, Remus was killed either by Romulus or by one of his supporters.[4] Romulus then went on to found the city of Rome, its institutions, government, military and religious traditions. He reigned for many years as its first king.

Primary Sources

It is widely agreed that the "canonical" version of Rome' foundation's myth contains elements from the Roman's own Indo-European origins, as well as Hellenistic elements that were included later. Definitively identifying those original elements has so far eluded the classical academic community.[5] Although the tale takes place before the founding of Rome around 750 BC, the earliest known written account of the myth is from the late 3rd century BC.[6] There is an ongoing debate about how and when the "complete" fable came together.[7]

Some elements are attested to earlier than others, and the story-line and tone were variously influenced by the circumstances and tastes of the different sources as well as by contemporary Roman politics and concepts of propriety.[8] Whether the twins' myth was a an original part of Roman myth or a later development is the subject of an ongoing debate.[7] Sources often contradict one another. These include the histories of Livy, Plutarch, Dionysius of Halicarnassus, and Tacitus as well as the work of Virgil and Ovid.[6][9][10] Quintus Fabius Pictor's work became authoritative to the early books of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita, Dionysius of Halicarnassus's Roman Antiquities, and Plutarch's Life of Romulus.[11]

These three works have been among the most widely read versions of the myth. In all three works, the tales of the lupercal and the fratricide are overshadowed by that of the twins' lineage and connections to Aeneas and the deposing of Amulius. The latter receives the most attention in the accounts. Plutarch dedicates nearly half of his account to the overthrow of their uncle.

Roman Antiquities (Dionysius)

Dionysius cites, among others, the histories of Fabius, Lucius Calpurnius Piso, Cato the Elder, Lucius Cincius Alimentus.

The first book of Dionysius' twenty-volume history of Rome does not mention Remus until page 235 (chapter 71). After spending another 8 chapters discussing the background of their birth in Alba, he and dedicates a total of 9 chapters to the tale (79-87). Most of that is spent discussing the conflict with Amulius.

He goes on to discuss the various accounts of the city's founding by others, and the lineage and parentage of the twins for another 8 chapters until arriving at the tale of their abandonment by the Tiber. He spends the better part of the chapter 79 discussing the survival in the wild. then the end of 79 through 84 on the account of their struggle with amulius. 84 with the non-fantastical account of their survival 294. Finally 295 is the augury 85-86, 87-88 the fratricide.303

Ab Urbe Condita (Livy)

Livy discusses the myth in chapters 4, 5, and 6 of his work's first book. p. 7 parentage 4 p. 8 survival. p. 8 the youth. 5 9-10 the struggle with amulius. 6 p. 11 (the beginning only) the augury and fratricide.

Life of Romulus (Plutarch)

2-10 (PG 96-119). First chapter is about alternative stories of their parentage 96. 97-98 common tale of parentage. 99-103 survival 104-105 youth. 105-113 overthrow. 114-118 fratricide

Fasti (Ovid)

Fasti, the epic Latin poem by Ovid from the early 1st century contains a complete account of the twins' tale. Notably, it relates a tale wherein the ghost of Remus appears to Faustulus and his wife, whom the poet calls "Acca". In the story, Remus appears to them while in bed and expresses his anger at Celer for killing him and his own, as well as Romulus' unquestioned fraternal love.

Roman History (Dio)

Roman History by Cassius Dio survives in fragment from various commentaries. They contain a more-or-less complete account. In them, he mentions an oracle that had predicted Amulius' death by a son of Numitor as the reason the Alban king expelled the boys. There is also a mention of "another Romulus and Remus" and another Rome having been founded long before on the same site.[12]

Origo Gentis Romanae (Unknown)

This work contains a variety of versions of the story. In one, there is a reference to a woodpecker bringing the boys food during the time they were abandoned in the wild. In one account of the conflict with Amulius, the capture of Remus is not mentioned. In stead, Romulus, upon being told of his true identity and the crimes suffered by him and his family at the hands of the Alban king, simply decided to avenge them. He took his supporters directly to the city and killed Amulius, afterwards restoring his grandfather to the throne.[13]

Fragments and other sources

- Annals by Ennius is lost, but fragments remain n later histories.

- Roman History by Appian, in Book I "Concerning the Kings" is a fragment containing an account of the twins parentage and orgins.

- The City of God Against the Pagans by Saint Augustine, claims, in passing, that Remus was alive after the city's founding. Both he and Romulus established the Roman Asylum after the traditional accounts claimed that he had died.[14]

- Historical Library by Diodorus Siculus, is a Universal history which survives mostly in tact in fragments and has a complete recounting of the twins' origins, their youth in the shepherd community, and the contest of the augury and fratricide. In this version, Remus sees no birds at all and he is later killed by Celer, Romulus' worker.

- Origines by Cato the Elder, fragments of which survive in the work of later historians, is cited by Dionysius.

Lost sources

- Quintus Fabius Pictor wrote in the 3rd century BC. His Greek History, written in Greek, is the earliest-known history of Rome. He is cited by all three canonical works.

- Diocles of Peparethus wrote a history of Rome which is cited by Plutarch.

- Lucius Calpurnius Piso wrote a history cited by Dionysius.

- Quintus Aelius Tubero wrote a history cited by Dionysius.

- Marcus Octavius (otherwise unknown) wrote an account cited in the Origio Gentis.

- Licinius Macer wrote an account cited in the Origio Gentis.

- Vennonius wrote an account cited in the Origio Gentis.

Modern scholarship

Modern scholarship approaches the various known stories of Romulus and Remus as cumulative elaborations and later interpretations of Roman foundation-myth. Particular versions and collations were presented by Roman historians as authoritative, an official history trimmed of contradictions and untidy variants to justify contemporary developments, genealogies and actions in relation to Roman morality. Other narratives appear to represent popular or folkloric tradition; some of these remain inscrutable in purpose and meaning. Wiseman sums the whole as the mythography of an unusually problematic foundation and early history.[15][16]

The three canonical accounts of Livy, Dionysius, and Plutarch provide the broad literary basis for studies of Rome's founding mythography. They have much in common, but each is selective to its purpose. Livy's is a dignified handbook, justifying the purpose and morality of Roman traditions of his own day. Dionysius and Plutarch approach the same subjects as interested outsiders, and include founder-traditions not mentioned by Livy, untraceable to a common source and probably specific to particular regions, social classes or oral traditions.[17][18] A Roman text of the late Imperial era, Origo gentis Romanae (The origin of the Roman people) is dedicated to the many "more or less bizarre", often contradictory variants of Rome's foundation myth, including versions in which Remus founds a city named Remuria, five miles from Rome, and outlives his brother Romulus.[19][20]

Roman historians and Roman traditions traced most Roman institutions to Romulus; he was thought to have founded Rome's armies, Senate and government, basic laws, citizen rights and responsibilities, religious institutions, earliest political alliances and even the patronage that underpinned both civil and military life. In reality, such developments would have been spread over a considerable span of time; some were much older, and others much more recent. To most Romans, the evidence for the veracity of the legend and its central characters seemed clear and concrete, an essential part of Rome's sacred topography; one could visit the cave where the twins were suckled by the she-wolf; or offer worship to the deified Romulus-Quirinus at his shepherd's hut; or watch a sacred play on the subject, or simply read the Fasti. Modern scholarship does not support an historical Romulus, or a Remus.

The legend as a whole encapsulates Rome's ideas of itself, its origins and moral values. For modern scholarship, it remains one of the most complex and problematic of all foundation myths, particularly in the manner of Remus's death. Ancient historians had no doubt that Romulus gave his name to the city. Most modern historians believe his name a back-formation from the name Rome; the basis for Remus's name and role remain subjects of ancient and modern speculation. The myth was fully developed into something like an "official", chronological version in the Late Republican and early Imperial era; Roman historians dated the city's foundation to between 758 and 728 BC, and Plutarch reckoned the twins' birth year as 771 BC. A tradition that gave Romulus a distant ancestor in the semi-divine Trojan prince Aeneas was further embellished, and Romulus was made the direct ancestor of Rome's first Imperial dynasty. Possible historical bases for the broad mythological narrative remain unclear and disputed.[21] The image of the she-wolf suckling the divinely fathered twins became an iconic representation of the city and its founding legend, making Romulus and Remus preeminent among the feral children of ancient mythography.

Historicity

Although a debate continues, at present, current scholarship offers little support for the actual occurrence of the tales from the Roman foundation myth, including an historical Romulus or Remus. Roman historians and Roman traditions traced most Roman institutions to Romulus; he was thought to have founded Rome's armies, Senate and government, basic laws, citizen rights and responsibilities, religious institutions, earliest political alliances and even the patronage that underpinned both civil and military life. In reality, such developments would have been spread over a considerable span of time; some were much older, and others much more recent.

Any possible historical bases for the broad mythological narrative remain unclear and disputed. The archaeologist Andrea Carandini is one of very few modern scholars who accept Romulus and Remus as historical figures, based on the 1988 discovery of an ancient wall on the north slope of the Palatine Hill in Rome. Carandini dates the structure to the mid-8th century BC and names it the Murus Romuli.[22] In 2007, archaeologists reported the discovery of the Lupercal beneath the home of Emperor Augustus, although a debate over the discovery continues.[23][24]

Iconography

Ancient pictures of the Roman twins usually follow certain symbolic traditions, depending on the legend they follow: they either show a shepherd, the she-wolf, the twins under a fig tree, and one or two birds (Livy, Plutarch); or they depict two shepherds, the she-wolf, the twins in a cave, seldom a fig tree, and never any birds (Dionysius of Halicarnassus).

The twins and the she-wolf were featured on what might be the earliest silver coins ever minted in Rome.[25]

The Franks Casket, an Anglo-Saxon ivory box (early 7th century AD) shows Romulus and Remus in an unusual setting, two wolves instead of one, a grove instead of one tree or a cave, four kneeling warriors instead of one or two gesticulating shepherds. According to one interpretation, and as the runic inscription ("far from home") indicates, the twins are cited here as the Dioscuri, helpers at voyages such as Castor and Polydeuces. Their descent from the Roman god of war predestines them as helpers on the way to war. The carver transferred them into the Germanic holy grove and has Woden's second wolf join them. Thus the picture served — along with five other ones — to influence "wyrd", the fortune and fate of a warrior king.[26]

In popular culture

- Romolo e Remo: a 1961 film starring Steve Reeves and Gordon Scott as the two brothers.

- The Rape of the Sabine Women: a 1962 film starring Wolf Ruvinskis as Romulus.

- In the Star Trek universe, Romulus and Remus are neighbouring planets with Remus being tidally locked to the star. Romulus is the capital of the Romulan Star Empire, which is loosely based on the Roman Empire.

- The novel Founding Fathers by Alfred Duggan describes the founding and first decades of Rome from the points of view of Marcus, one of Romulus's Latin followers, Publius, a Sabine who settles in Rome as part of the peace agreement with Tatius, Perperna, an Etruscan fugitive who is accepted into the tribe of Luceres after his own city is destroyed, and Macro, a Greek seeking purification from blood-guilt who comes to the city in the last years of Romulus's reign. Publiusa and Perpernia become senators. Romulus is portrayed as a gifted leader though a remarkably unpleasant person, chiefly distinguished by his luck; the story of his surreptitious murder by the senators is adopted, but although the story of his deification is fabricated, his murderers themselves think he may indeed have become a god. The novel begins with the founding of the city and the killing of Remus, and ends with the accession of Numa Pompilius.

- In the game Undead Knights, the main characters are brothers named Romulus and Remus.

- In Harry Potter, one of the characters is named after Remus—Remus John Lupin. And at one point uses the code name Romulus. Professor Lupin is a teacher of defence against the dark arts, and is in fact a werewolf. This reflects the Remus of Roman mythology, who was raised by a wolf. In fact, the name Lupin comes from the Latin word lupus, meaning wolf.

- In Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood Romulus is worshipped as a god by the Followers of Romulus cult. The main character, Ezio Auditore, comes into conflict with the cult on several occasions during his adventures in Rome while trying to locate the keys to the Armor of Brutus, wiping out the cult in the process.[27]

- In the Death Grips song, "Black Quarterback" Romulus and Remus are mentioned. In characteristic Death Grips style, their lyric isn't contextualised in any typical linear sense.

- "Up the Wolves" by The Mountain Goats is a song that alludes to Romulus and Remus.

- Ex Deo released an album in 2009 titled Romulus. Its title track concerns the myth of Romulus and Remus and the founding of Rome.

Depictions in Art

The myth has been an inspiration to artists throughout the ages. Particular focus has been paid to the rape of Ilia by Mars and the suckling of the twins by the she-wolf.

Palazzo Magnani

In the late 16th century, the wealthy Magnani family from Bologna commissioned a series of artworks based on the Roman foundation myth. The artists contributing works included a sculpture of Hercules with the infant twins by Gabriele Fiorini, featuring the patron's own face. The most important works were an elaborate series of frescoes collectively known as Histories of the Foundation of Rome by the Brothers Carracci: Ludovico, Annibale, and Agostino Carracci.

-

Hercules Priapus, Gabriele Fiorini

-

Salone Carracci Palazzo Magnani

-

She-Wolf Suckling Romulus and Remus (Ludavico)

-

Remus and the Cattle Thieves (attributed to one or more of the Carraccis)

-

Remus being brought before King Amulius (attributed to one or more of the Carraccis)

-

The death of Amulius

Fresco of Palazzo Trinci

The Loggia di Romolo e Remo is an unfinished, 15th century fresco by Gentile da Fabriano depicting episodes from the legend in the Palazzo Trinci.

-

The rape of the vestal Rhea Silvia by Mars

-

The birth of Romulus and Remus

-

Loggia di romolo e remo 08

-

Faustulus finding Romulus and Remus

-

Faustulus bringing the twins to his wife Acca Laurentia

-

The deposing of Amulius

Late antiquity

-

Depiction of the goddess Roma and the Capitoline Wolfe (4th century)

-

Detail of a mosaic with Romolus and Remus, (c.510), Photograph by Ma'arrat al-Numan (2010)

-

.jpg)

Mosaic depicting the She-wolf with Romulus and Remus, from Aldborough, (c.300 AD), Leeds City Museum (16025914306)

Middle ages and Pre-Renaissance

-

Woodcut illustration of Rhea Silvia and the birth of Romulus and Remus attributed to Johann Zainer (15th century)

-

Illuminated manuscript of Livy's Ab Urbe Condita Libri, (c.1370)

-

14th century depiction of Romulus and Remus

-

_-_n._8226_-_Certosa_di_Pavia_-_Medaglione_sullo_zoccolo_della_facciata.jpg)

Detail from the facade of the Certosa di Pavia, Giovanni Antonio Amadeo (c.1485), photograph by Carlo Brogi (1850-1925)

-

Romolo e Remo, unknown (c.1520)

Renaissance

-

Faustulus (to the right of picture) discovers Romulus and Remus with the she-wolf and woodpecker. Their mother Rhea Silvia and the river-god Tiberinus witness the moment. Painting by Peter Paul Rubens, c. 1616 (Capitoline Museums)

-

Romulus and Remus nursed by the she-wolf, stucco detail, ceiling of the Grand Cabinet of the Queen, Sully wing, Louvre Museum, Michel Anguier (17th century)

-

Bellona with Romulus and Remus, Alessandro Turchi (15th-16th century)

-

Landscape with She-Wolf Suckling Romulus and Remus, Annibale Carracci (c. 1590)

-

Mars and Rhea Silvia, Nicolas Colombel (1694)

-

Tapestry: Mars appears to Rhea Silvia, No. 8 in a series (History of the Consul Decius Mus), Rubens (c.1629)

-

Mars and the Vestal Virgin, Jacques Blanchard (c.1630)

18th-20th century

-

Comic History of Rome p 007 Remus jumping over the Walls, John Leech, (c.1850)

-

_-_Foto_Giovanni_Dall'Orto_-_18-May-2007.jpg)

Detail from the base of the Monument for the garibaldini who fell at Mentana, Luigi Belli (1844-1919), "Piazza Mentana" square in Milan

-

Hungarian postage stamp commemorating the 1960 Olympic Games

-

The Goddess Roma and the King of Rome, Bartolomeo Pinelli (1811)

-

the Discovery of Romulus and Remus Vincenzo Camuccini (1820)

See also

- Asena, a similar legend concerning the origin of the Turks

- Castor and Pollux

- Dioscuri

- The Golden Bough, a tale concerning Aeneas and Rome

- Greco-Roman world

- Lares

- Proto-Indo-European religion, §Brothers

- Senius and Aschius, the legendary twin founders of Siena

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Romulus and Remus. |

- Plutarch (Lives of Romulus, Numa Pompilius, Camillus)

- Romulus and Remus (Romwalus and Reumwalus) and two wolves on the Franks Casket: Franks Casket, Helpers on the way to war

- Romulous and Remus on the Ara Pacis Augustae

Further reading

- Albertoni, Margherita, et al. The Capitoline Museums: Guide. Milan: Electa, 2006. For information on the Capitoline She-Wolf.

- Beard, M., North, J., Price, S., Religions of Rome, vol. 1, illustrated, reprint, Cambridge University Press, 1998. ISBN 0-521-31682-0

- Cornell, T. (1995), The Beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars (c. 1000–264 BC), Routledge, ISBN 978-1-136-75495-1

- Mazzoni, Cristina (29 March 2010). She-Wolf: The Story of a Roman Icon. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-19456-3. Retrieved 2 December 2016.

- Wiseman, T. P., Remus: a Roman myth, Cambridge University Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-521-48366-7

Bibliography

Primary sources

- Dionysius of Halicarnassus. "Roman Antiquities". doi:10.4159/DLCL.dionysius_halicarnassus-roman_antiquities.1937. Retrieved 19 November 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

- Livy. "History of Rome". doi:10.4159/DLCL.livy-history_rome_1.1919. Retrieved 7 November 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

- Plutarch, "The life of Romulus", in Thayer, The Parallel Lives, Chicago, IL, USA: Loeb.

- Ovid. "Fasti". doi:10.4159/DLCL.ovid-fasti.1931. Retrieved 25 November 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

Secondary sources

- Crawford, Michael Hewson (1985), Coinage and Money Under the Roman Republic: Italy and the Mediterranean Economy, University of California Press, ISBN 978-0-520-05506-3, retrieved 30 November 2016

- Tennant, PMW (1988). "The Lupercalia and the Romulus and Remus Legend" (PDF). Acta Classica. XXXI: 81–93. ISSN 0065-1141. Retrieved 19 November 2016.

- Wiseman, Timothy Peter (25 August 1995), Remus: A Roman Myth, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 978-0-521-48366-7, retrieved 30 November 2016

Notes

- ↑ Adriano La Regina, "La lupa del Campidoglio è medievale la prova è nel test al carbonio". La Repubblica. 9 July 2008

- ↑ Other sources express doubt as to the divine nature of their parentage. One claims the boys were fathered by Amulius himself, who raped his niece while wearing his armor to conceal his identity.

- ↑ For other depictions, see Livy and Dionysius

- ↑ Dionysius lays out several of the different accounts of his death, along with his murder by Romulus.

- ↑ Tennant, p. 81

- 1 2 Dionysius, vol 1 p. 72

- 1 2 Tennant

- ↑ Wiseman, Remus

- ↑ Dionysius, vol. II p. 76

- ↑ Plutarch, Lives

- ↑ von Albrecht, Michael (1997), A History of Roman Literature: From Livius Andronicus to Boethius, I, Leiden: BRILL, p. 374, ISBN 90-04-10709-6, retrieved 20 November 2016

- ↑ Dio Casssius. "Roman History I p.12-18". doi:10.4159/DLCL.dio_cassius-roman_history.1914. Retrieved 24 November 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

- ↑ Origio Gentis Romanae XXI

- ↑ Saint Augustine. "The City of God Against the Pagans v.I p.137". doi:10.4159/DLCL.augustine-city_god_pagans.1957. Retrieved 24 November 2016. – via digital Loeb Classical Library (subscription required)

- ↑ Wiseman Remus.

- ↑ Momigliano, Arnoldo (2007), "An interim report on the origins of Rome", Terzo contributo alla storia degli studi classici e del mondo antico, 1, Rome, IT: Edizioni di storia e letteratura, pp. 545–98. A critical, chronological review of historiography related to Rome's origins.

- ↑ Momigliano, Arnoldo (1990), The classical foundations of modern historiography, University Presses of California, Columbia and Princeton, p. 101. Modern historiographic perspectives on this source material.

- ↑ Dillery (2009), Feldherr, Andrew, ed., The Cambridge Companion to the Roman Historians, Cambridge University Press, pp. 78–81 ff..

- ↑ Cornell, pp. 57-8.

- ↑ Banchich (2004), Origo Gentis Romanae (PDF), trans. by Haniszewski, et al., Cansius College. Translation and commentaries.

- ↑ The archaeologist Andrea Carandini is one of very few modern scholars who accept Romulus and Remus as historical figures, based on the 1988 discovery of an ancient wall on the north slope of the Palatine Hill in Rome. Carandini dates the structure to the mid-8th century BC and names it the Murus Romuli. See Carandini, La nascita di Roma. Dèi, lari, eroi e uomini all'alba di una civiltà (Torino: Einaudi, 1997) and Carandini. Remo e Romolo. Dai rioni dei Quiriti alla città dei Romani (775/750 - 700/675 a. C. circa) (Torino: Einaudi, 2006)

- ↑ See Carandini, La nascita di Roma. Dèi, lari, eroi e uomini all'alba di una civiltà (Torino: Einaudi, 1997) and Carandini. Remo e Romolo. Dai rioni dei Quiriti alla città dei Romani (775/750 - 700/675 a. C. circa) (Torino: Einaudi, 2006)

- ↑ Valsecchi, Maria Cristina (26 January 2007). "Sacred Cave of Rome's Founders Discovered, Archaeologists Say". National Geographic News. National Geographic. Retrieved 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Schulz, Matthia. "Is Italy's Spectacular Find Authentic?" Spiegel Online, 10 November 2016.

- ↑ Crawford, p.31

- ↑ ; see also "The Travelling Twins: Romulus and Remus in Anglo-Saxon England

- ↑ Assassin's Creed: Brotherhood