Demetrius I of Macedon

| Demetrius | |

|---|---|

Marble bust of Demetrius I Poliorcetes. Roman copy from 1st century AD of a Greek original from 3rd century BC | |

| King of Macedonia | |

| Reign | 294–288 BC |

| Predecessor | Antipater II of Macedon |

| Successor | Lysimachus and Pyrrhus of Epirus |

| Born | 337 |

| Died | 283 |

| Spouse | Phila, Eurydice of Athens, Deidamia I of Epirus, Lanassa, Ptolemais |

| Issue |

Stratonice of Syria Antigonus II Gonatas Demetrius the Fair |

| Father | Antigonus I Monophthalmus |

| Mother | Stratonice |

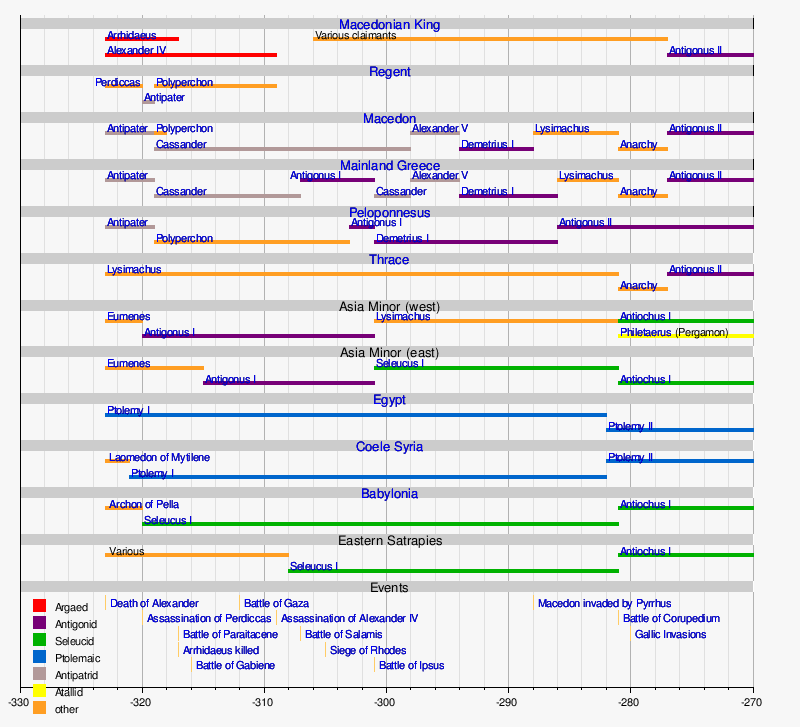

Demetrius I (/dɪˈmiːtriəs/; Greek: Δημήτριος; 337–283 BC), called Poliorcetes (/ˌpɒli.ɔːrˈsiːtiːz/; Greek: Πολιορκητής, "The Besieger"), son of Antigonus I Monophthalmus and Stratonice, was a Macedonian Greek nobleman, military leader, and finally king of Macedon (294–288 BC). He belonged to the Antigonid dynasty and was its first member to rule Macedonia.

Biography

At the age of twenty-two he was left by his father to defend Syria against Ptolemy the son of Lagus. He was defeated at the Battle of Gaza, but soon partially repaired his loss by a victory in the neighbourhood of Myus.[1] In the spring of 310, he was soundly defeated when he tried to expel Seleucus I Nicator from Babylon; his father was defeated in the autumn. As a result of this Babylonian War, Antigonus lost almost two thirds of his empire: all eastern satrapies fell to Seleucus.

After several campaigns against Ptolemy on the coasts of Cilicia and Cyprus, Demetrius sailed with a fleet of 250 ships to Athens. He freed the city from the power of Cassander and Ptolemy, expelled the garrison which had been stationed there under Demetrius of Phalerum, and besieged and took Munychia (307 BC). After these victories he was worshipped by the Athenians as a tutelary deity under the title of Soter (σωτήρ) ("Preserver").[1]

In the campaign of 306 BC he defeated Ptolemy and Menelaus, Ptolemy's brother, in the naval Battle of Salamis, completely destroying the naval power of Ptolemaic Egypt.[1] Demetrius conquered Cyprus in 306 BC, capturing one of Ptolemy's sons.[2] Following the victory Antigonus assumed the title king and bestowed the same upon his son Demetrius. In 305 BC, now bearing the title of king bestowed upon him by his father, he endeavoured to punish the Rhodians for having deserted his cause; his ingenuity in devising new siege engines in his unsuccessful attempt to reduce the capital gained him the title of Poliorcetes.[1] Among his creations were a battering ram 180 feet (55 m) long, requiring 1000 men to operate it; and a wheeled siege tower named "Helepolis" (or "Taker of Cities") which stood 125 feet (38 m) tall and 60 feet (18 m) wide, weighing 360,000 pounds.

.jpg)

In 302 BC he returned a second time to Greece as liberator, and reinstated the Corinthian League. But his licentiousness and extravagance made the Athenians long for the government of Cassander.[1] Among his outrages was his courtship of a young boy named Democles the Handsome. The youth kept on refusing his attention but one day found himself cornered at the baths. Having no way out and being unable to physically resist his suitor, he took the lid off the hot water cauldron and jumped in. His death was seen as a mark of honor for himself and his country. In another instance, Demetrius waived a fine of 50 talents imposed on a citizen in exchange for the favors of Cleaenetus, that man's son.[3] He also sought the attention of Lamia, a Greek courtesan. He demanded 250 talents from the Athenians, which he then gave to Lamia and other courtesans to buy soap and cosmetics.[3]

He also roused the jealousy of Alexander's Diadochi; Seleucus, Cassander and Lysimachus united to destroy him and his father. The hostile armies met at the Battle of Ipsus in Phrygia (301 BC). Antigonus was killed, and Demetrius, after sustaining severe losses, retired to Ephesus. This reversal of fortune stirred up many enemies against him—the Athenians refused even to admit him into their city. But he soon afterwards ravaged the territory of Lysimachus and effected a reconciliation with Seleucus, to whom he gave his daughter Stratonice in marriage. Athens was at this time oppressed by the tyranny of Lachares—a popular leader who made himself supreme in Athens in 296 BC—but Demetrius, after a protracted blockade, gained possession of the city (294 BC) and pardoned the inhabitants for their misconduct in 301.[1]

King of Macedonia

In 294 he established himself on the throne of Macedonia by murdering Alexander V, the son of Cassander.[1] He faced rebellion from the Boeotians but secured the region after capturing Thebes in 291 BC. That year he married Lanassa, the former wife of Pyrrhus. But his new position as ruler of Macedonia was continually threatened by Pyrrhus, who took advantage of his occasional absence to ravage the defenceless part of his kingdom (Plutarch, Pyrrhus, 7 if.); at length, the combined forces of Pyrrhus, Ptolemy and Lysimachus, assisted by the disaffected among his own subjects, obliged him to leave Macedonia in 288 BC.[1]

After besieging Athens without success he passed into Asia and attacked some of the provinces of Lysimachus with varying success. Famine and pestilence destroyed the greater part of his army, and he solicited Seleucus' support and assistance. But before he reached Syria hostilities broke out, and after he had gained some advantages over his son-in-law, Demetrius was totally forsaken by his troops on the field of battle and surrendered to Seleucus.

His son Antigonus offered all his possessions, and even his own person, in order to procure his father's liberty. But all proved unavailing, and Demetrius died after a confinement of three years (283 BC). His remains were given to Antigonus and honoured with a splendid funeral at Corinth. His descendants remained in possession of the Macedonian throne till the time of Perseus, when Macedon was conquered by the Romans in 168 BC.[1]

Family

Demetrius was married five times:

- His first wife was Phila daughter of Regent Antipater by whom he had two children: Stratonice of Syria and Antigonus II Gonatas.

- His second wife was Eurydice of Athens, by whom he is said to have had a son called Corrhabus.[5]

- His third wife was Deidamia, a sister of Pyrrhus of Epirus. Deidamia bore him a son called Alexander who is said by Plutarch to have spent his life in Egypt, probably in an honourable captivity.[6]

- His fourth wife was Lanassa, the former wife of his brother-in-law Pyrrhus of Epirus.

- His fifth wife was Ptolemais, daughter of Ptolemy I Soter and Eurydice of Egypt, by whom he had a son called Demetrius the Fair.

He also had an affair with a celebrated courtesan called Lamia of Athens, by whom he had a daughter called Phila.

Literary references

Plutarch

Plutarch wrote a biography of Demetrius.

Hegel

Hegel, in the Lectures on the History of Philosophy, says of another Demetrius, Demetrius Phalereus that "Demetrius Phalereus and others were thus soon after [Alexander] honoured and worshipped in Athens as God."[7] What the exact source was for Hegel's claim is unclear. Diogenes Laërtius in his short biography of Demetrius Phalereus does not mention this.[8] Apparently Hegel's error comes from a misreading of Plutarch's Life of Demetrius which is about Demetrius Poliorcetes and not Demetrius of Phalereus. Plutarch describes in the work how Demetrius Poliorcetes conquered Demetrius Phalereus at Athens. Then, in chapter 12 of the work, Plutarch describes how Demetrius Poliorcetes was given honors due to the god Dionysus. This account by Plutarch was confusing not only for Hegel, but for others as well.[9]

Others

Plutarch's account of Demetrius' departure from Macedonia in 288 BC inspired Constantine Cavafy to write "King Demetrius" (ὁ βασιλεὺς Δημήτριος) in 1906, his earliest surviving poem on a historical theme.

Demetrius is the main character of the opera Demetrio a Rodi (Turin, 1789) with libretto[10] by Giandomenico Boggio and Giuseppe Banti. The music is set by Gaetano Pugnani (1731-1798).

Demetrius appears (under the Greek form of his name, Demetrios) in L. Sprague de Camp's historical novel, The Bronze God of Rhodes, which largely concerns itself with his siege of Rhodes.

Alfred Duggan's novel Elephants and Castles provides a lively fictionalised account of his life.

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Demetrius s.v. Demetrius I". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 982.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Demetrius s.v. Demetrius I". Encyclopædia Britannica. 7 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 982. - ↑ Walter M. Ellis, Ptolemy of Egypt, Routledge, London, 1994, p. 15.

- 1 2 Plutarch, Life of Demetrius

- ↑ Prado Museum: "Retrato en bronce de un Diádoco"

- ↑ Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology. p. 120. Retrieved 1 December 2015.

- ↑ Plutarch, "Demetrius", 53

- ↑ Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, Lectures on the History of Philosophy, volume 2, Plato and the Platonists, p. 125, translated by E. S. Haldane and Frances H. Simson, Lincoln, Nebraska: University of Nebraska Press, 1995.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, Book V.

- ↑ Kenneth Scott, "The Deification of Demetrius Poliorcetes: Part I", The American Journal of Philology, 49:2 (1928), pp. 137–166. See, in particular, p. 148.

- ↑ Demetrio a Rodi: festa per musica da rappresentarsi nel Regio teatro di Torino per le nozze delle LL. AA. RR. Vittorio Emanuele, 48p. Published by Presso O. Derossi, 1789.

Sources

Ancient sources

- Plutarch, Life of Demetrius

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History, books 19–21

- Polyaenus, Stratagems, 4.7

- Justin, Epitome of Trogus, books 15–16

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophists, 6.252–255

Modern works

- R. M. Errington, A History of the Hellenistic World, pp. 33–58. Blackwell Publishing (2008). ISBN 978-0-631-23388-6.

- Demetrius I at Livius.org

- Billows, Richard A. (1990). Antigonos the One-Eyed and the Creation of the Hellenistic State. Berkeley and Los Angeles, California: University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-20880-3.

- Alfred Duggan, "Besieger of Cities"

| Regnal titles | ||

|---|---|---|

| Preceded by Antigonus I Monophthalmus |

Antigonid dynasty | Succeeded by Antigonus II Gonatas |

| Preceded by Antipater II of Macedon |

King of Macedon 294–288 BC |

Succeeded by Lysimachus and Pyrrhus of Epirus |