Rigel in fiction

The planetary systems of stars other than the Sun and the Solar System are a staple element in much science fiction.

The star Rigel

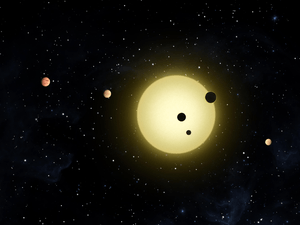

Rigel (Beta Orionis) is a luminous blue supergiant of spectral type B8 Iae,[1] in the constellation Orion, that is frequently featured in works of science fiction. The star is actually a visual binary, with the secondary component Rigel B itself being a spectroscopic binary that has never been resolved visually, and which taken as a single source is 500 times dimmer and over 2200 AU from its overwhelming companion Rigel A ("Rigel").[2] This irregular variable star is the most luminous in our local region of the Milky Way; at about 71 times the diameter of the Sun it would, if viewed from a hypothetical planet at a distance of 1 AU, subtend an angle of 35° in the sky—when rising or setting it would extend from the horizon almost halfway up the sky—and it would shine at a lethal magnitude of −38 (see graphic).[1]

There is no evidence that the Rigel system hosts any extrasolar planets.[3] However, several creators of works of science fiction have chosen to populate it with an unusually large family of worlds (see The Stars My Destination by Alfred Bester, Demon Princes by Jack Vance, and Star Trek below).

Rigel is the brightest star in the constellation Orion and the sixth brightest star in the sky, with an apparent magnitude of 0.18. Although it has the Bayer designation "Beta," it is almost always brighter than Alpha Orionis (Betelgeuse). Whereas the latter star represents the right shoulder of the Hunter, Rigel represents his left foot. It is the first star counterclockwise from Sirius in the Winter Hexagon, and is followed in turn by Aldebaran.

The star's name is a contraction of Riǧl Ǧawza al-Yusra, this being Arabic for left foot of the central one. Another Arabic name is رجل الجبار, riǧl al-ǧabbār, that is, the foot of the great one.[note 1] It figures prominently in the mythologies of Egypt, China, Japan, and Oceania.

General uses of Rigel

Rigel may be referred to in fictional works for its metaphorical (meta) or mythological (myth) associations, or else as a bright point of light in the sky of the Earth, but not as a location in space or the center of a planetary system:

- Mardi, and a Voyage Thither (1849), novel by Herman Melville. In this, his third novel, Melville is comparing archipelagoes of stars to the scatterings of islands he has visited on his exploration of the south seas: And as in Orion, to some old king-astronomer, — say, King of Rigel, or Betelguese, — this Earth's four quarters show but four points afar'; so, seem they to terrestrial eyes, that broadly sweep the spheres. / And, as the sun, by influence divine, wheels through the Ecliptic; threading Cancer, Leo, Pisces, and Aquarius; so, by some mystic impulse am I moved, to this fleet progress, through the groups in white-reefed Mardi's zone.[5] (meta)

- Clarel (1876), epic poem written by Herman Melville. In this 18,000 line poem, the longest in American literature, Melville describes a pilgrimage to the Holy Land: When, afterward, in nature frank / Upon the terrace thrown at ease / Like magi of the old Chalda-a / Viewing Rigel and Betelguese / We breathed the balm-wind from Saba-a.[6] (sky)

- Ben-Hur (1880), novel by General Lew Wallace. Judah Ben-Hur returns to Jerusalem as the adopted "young Quintus Arrius," and has the chance to revenge himself against his erstwhile friend-turned-enemy, the tribune Messala, by defeating him in a great chariot race. He will race the four eager white Arabians of Sheik Ilderim, who are named after stars: Ha, Antares — Aldebaran! Shall he not, O honest Rigel? and thou, Atair, king among coursers, shall he not beware of us? Ha, ha! good hearts.[7] (myth)

- The Old Man and the Sea (1952), novel by Ernest Hemingway. The Old Man Santiago sees Rigel at sunset off the coast of Cuba: It was dark now as it becomes dark quickly after the sun sets in September ... The first stars were out. He did not know the name of Rigel but he saw it and knew soon they would all be out and he would have all his distant friends.[note 2][8] (sky)

There follow references to Rigel as a location in space or the center of a planetary system, categorized by genre:

Literature

- Tékumel (~1940– ), novels and games by M. A. R. Barker. Rigel is the home star of the ngékka, a delicate, six-legged riding beast (riding beasts are extremely rare on Tékumel), thought to be mythological.

- The Lensman Series (1934–48), novels by E. E. "Doc" Smith. The Lensman series takes place on many different worlds over a vast sweep of space. The ancient supercivilization of the Arisians, originators of the "lens," initiates a breeding program for potential godlike heroes, the Lensmen, on four worlds of high potential, including the Earth and Rigel IV—the latter a hot, high-gravity world. "L2" (Second-Stage Lensman) Kimball Kinnison is the product of the program on Earth, and L2 Tregonsee is the Rigellian. Smith's work is strongly identified with the beginnings of US pulp science fiction as a separate marketing genre, and did much to define its essential territory, galactic space, featuring many planets such as those orbiting Rigel. The Lensman series is considered far superior to Smith's Skylark series.[9]

- Empire series (1945–1952), short story and three novels by Isaac Asimov set early in the history of the Galactic Empire that later dominated his overarching Foundation Series of novels. Rigel, the name of the star, is assumed by one of its planets in the Empire series. In the first millennium of the Galactic Era, this world's inhabitants developed a robot-based civilization that became so decadent and lazy that the effete Rigellians fell easy victim to the depredations of the warlord Moray.

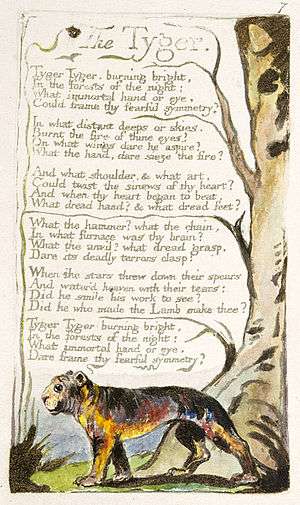

- The Stars My Destination (1956), classic science fiction novel (titled Tiger! Tiger! in the UK) written by Alfred Bester, and doubly inspired by Alexandre Dumas' The Count of Monte Cristo and William Blake's poem "The Tyger" (see graphic). After his apotheosis in the burning cathedral, the legendary Gully Foyle teleports stark naked to the vicinity of several stars, including Rigel: "burning blue-white, five hundred and forty light years from earth, ten thousand times more luminous than the sun, a cauldron of energy circled by thirty-seven massive planets ..."[note 3][12] The interstellar "jaunting" sequence is typical of Bester's signature pyrotechnics, his quick successions of hard, bright images, and mingled images of decay and new life.[13]

- Next of Kin (1959), novel by Eric Frank Russell. Private Leeming is every sergeant's worst nightmare: immune to military discipline and punishment, and given to random acts of insubordination. Thus when a mission to fly a prototype spaceship behind enemy lines comes up, he is the natural candidate to pilot the dangerous but potentially strategic spy mission—one from which he is unlikely to return alive. Once on the job, racks up visits to 72 planets before finally approaching Rigel, the home system of a humanoid, rubber-limbed, pop-eyed, and consistently "friendly" alien race who speak a language eerily similar to English ...[14] (Compare "Hungry are the Damned" below.)

- Adaptation (1960), novelette by Mack Reynolds appearing in Astounding Science Fiction. Humanity is obsessed with the goal of colonizing every single one of the galaxy's millions of earthlike worlds, and they know how to do it: On each even semi-habitable new planet, a colony of a mere few hundred brave souls is seeded; inevitably they quickly revert to barbarism; more often than not, after a standard thousand years, they somehow adapt and develop a civilization peculiarly suited to their strange new home. Such is the case for Rigel, whose planets Genoa and Texcoco are "all but unbelievably Earthlike. Almost all [the] flora and fauna have been adaptable. Certainly [our] race has been." After the requisite millennium, protagonist Amschel Mayer is sent in to take charge as a godlike interloper, to mold the young societies as he sees fit ...[15] Reynolds' Adaptation, like "most of his later works, is unashamedly didactic, although not doctrinaire." (Reynolds was a lifelong socialist.)[16]

- Demon Princes (1964–1981), series of five novels written by Jack Vance. In Vance's Oikumene universe, Rigel is one of the three principal centers of human civilization (together with the Earth and Vega), the Rigel Concourse consisting of "twenty-six magnificent planets, most of them not only habitable but salubrious."[17] The system was discovered by interstellar explorer Sir Julian Hove, who provided its worlds with a stuffy and bombastic list of names culled from a pantheon of Victorian notables. The compendium was intercepted by one Roger Pilgham, a bored transmission clerk who substituted a far more fanciful schedule of names, which gained wide acceptance:

|

|

|

|

|

- Notable locations in the Concourse include:

- • The Esplanade, facing the Thaumaturge Ocean at Avente on Alphanor, and Kirth Gersen's base of operations.[18]

- • The Patch Engineering and Construction Company of Patris on Krokinole, where Gersen builds a faux monster, the dnazd, to the specifications and for the use of the Demon Prince Kokor Hekkus on the fantasy planet Thamber.[19]

- • The Feritse Precision Instruments Company, at Sansontiana on Olliphane, where Gersen takes up the trail of the descrambling strip to Lugo Teehalt's locator monitor—a decoder that will reveal the whereabouts of a secret paradise world.[20]

- "The first full-fleged modern planetary romance is therefore probably Jack Vance's ... [he] supplied sf writers with a model to exploit." Vancian worlds of the Oikumene provide a rich environment together with off-world protagonists (In the case of the above locations: Kirth Gersen) whose need to travel across the planet provides a quest plot and a rationale for the lessons in anthropology and sociology so common to the form.[21]

- The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy (1979), novel by Douglas Adams. Orion Beta is a star system noted for its madranite mining belts. At a hyperspace port catering to the belts, Ford Prefect is taught by the local miners to play a telepathic drinking game similar to Earth's indian wrestling, except that the players imbibe Ol' Janx Spirit, a main ingredient in the Pan Galactic Gargle Blaster. Judging by the star's name, the location of all this is likely to be in the Rigel (Beta Orionis) system.[22]

- Night Train to Rigel (2005), the first novel in the Quadrail series written by Timothy Zahn. Government agent Frank Compton is enlisted by the arachnoid operators of the eponymous intra-galactic rail system to investigate the possibility of a certain WMD being able to slip past their security barriers. To aid in his inquiries, he is provided with an unlimited travel pass enabling him to travel, along with a female companion Bayta, to the ends of the galaxy—and in particular to the Rigel star system.[note 4]

- Out Around Rigel by Robert H. Wilson, downloadable from https://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/20553

Film and television

Star Trek

The items in this subsection all refer to works in the film, television, and print franchise originated by Gene Roddenberry. In the Star Trek universe, Rigel lends its name to at least twelve planets—a large number for a fictional universe—many of which have been colonized by the Federation.

Not all of these worlds are in the Beta Orionis planetary system (see graphic), and the name Rigel is used to describe at least one other star by some aliens. It is also unclear which, if any, of these bodies is home to the Rigellians, a reptilian race seen in Star Trek: The Motion Picture, and distinct from the "one-l" Rigelians of Rigel V.

Note also that, unlike many creators of works of science fiction, Star Trek eschews the use of common names for imaginary extrasolar worlds, instead consistently using (or misusing) the Roman numeral convention (Starname I, II, III, ...[23])—and never the modern astronomical convention (Starname b, c, d, ...[24]).

- "The Cage" (1965; first aired complete in 1988), original pilot episode of Star Trek: The Original Series written by Gene Roddenberry and directed by Robert Butler. Much of the story's footage was repurposed in the two-part episode "The Menagerie" (1966), written by Roddenberry and directed by Marc Daniels. Captain Christopher Pike and a landing party from the USS Enterprise are attacked inside an apparently abandoned fortress on Rigel VII by native Kalar warriors. Three crew members are killed, and seven more are seriously injured. Pike later regretted his decision to enter the fortress, stating that "the swords and the armor" should have alerted him to the possibility of a trap.

- "Mudd's Women" (1966), episode of Star Trek: The Original Series written by Gene Roddenberry and directed by Harvey Hart. The notorious Harcourt Fenton Mudd and three extraordinarily beautiful women are rescued by the USS Enterprise—to the burgeoning distraction of the crew. The Enterprise itself is damaged in the adventure, and limps to the harsh, stormy desert planet Rigel XII, where unknown to Captain Kirk, Mudd secretly cements plans to sell the women to the local miners. (Compare Deneb: "I, Mudd".)

- "Shore Leave" (1966), episode of Star Trek: The Original Series written by Theodore Sturgeon and directed by Robert Sparr. Back in his salad days, while enjoying youthful indiscretions on the resort planet Rigel II, Dr. McCoy had become well acquainted with a couple of scantily-clad ladies from a cabaret chorus line. Now, years later, on the fantasy-fulfilling "Shore Leave" planet, the alluring pair are physically recreated from his imagination. He also meets a white rabbit—who complains of being late.

- "Journey to Babel" (1967), episode of Star Trek: The Original Series written by D. C. Fontana and directed by Joseph Pevney. Intrigue abounds as an assortment of ambassadors, both real and dissembled, and including the first appearance Mr. Spock's father Sarek, board the USS Enterprise en route to negotiations on the neutral planetoid Babel. The subject of this diplomatic exercise is controversial: Shall the Coridan system, a prime but hotly contested natural source of dilithium crystals, be admitted to the Federation? The Rigelians of Rigel V (similar in physiology to the Vulcans but possessed of four or five genders) also want to join, and they finally become members in 2184.[25]

- "Wolf in the Fold" (1967), episode of Star Trek: The Original Series written by Robert Bloch and directed by Joseph Pevney. "Scotty" (Chief Engineer Scott) is accused of the brutal murder of several female acquaintances on the planet Argelius II—killings actually carried out by an enigmatic and misogynistic entity that has cut an ancient and bloody swath across the galaxy, appearing variously through history as Jack the Ripper on the Earth, and as the woman-killer "Beratis" on the planet Rigel IV.

- "The Passenger" (1993), episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine written by Morgan Gendel et al. and directed by Paul Lynch. During the 2360s, Kobliad fugitive Rao Vantika used a subspace shunt to access and purge everything in the active memory of computer systems on Rigel VII. In the episode he seizes mind control of one of Deep Space 9's officers and attempts the same method of attack on the station itself.

- "All Good Things ..." (1994), episode of Star Trek: The Next Generation written by Brannon Braga and Ronald D. Moore, and directed by Winrich Kolbe. Through the machinations of the capricious super-being Q, Captain Picard finds his subjective present jumping between now, 25 years ago, and 25 years from now. In his "ago" state, the USS Enterprise had just been joined by Lt. Geordi La Forge, who "now" has retired, become a novelist, and lives with the wife and kids on Rigel III.

- "The Wire" (1994), episode of Star Trek: Deep Space Nine written by Robert Hewitt Wolfe and directed by Kim Friedman. The Cardassian character Garak is revealed to be a former member of the Obsidian Order, the much-feared Cardassian intelligence service, when the interrogation-resisting implant in his brain begins to fail. Meanwhile, Keiko O'Brien—the wife of the station's Chief Operations Officer Miles O'Brien—attends a week-long hydroponics conference on the planet Rigel IV.

- "Broken Bow" (2001), pilot episode of Star Trek: Enterprise written by Rick Berman and Brannon Braga, and directed by James Conway. The Klingon courier spy Klaang is pursued across the galaxy by Jonathan Archer and the crew of the Enterprise (NX-01), and the pursuit passes through Rigel Colony—a 36-level trade complex populated by numerous sentient species, huge houseflies, and gorgeous butterflies—on the ice planet Rigel X. In the bookend final episode of the series, "These Are the Voyages..." (2005), written by Berman and Braga, directed by Allan Kroeker, and fashioned as a prequel lead-in to Star Trek: The Original Series, Rigel X (the original 36-level sets were re-used) is the final world visited by Captain Jonathan Archer and the Enterprise before its decommissioning.

Other film and television

- "The Plot to Kill a City" (1979), episodes 106 and 107 in the television series Buck Rogers in the 25th Century written by Alan Brennert and directed by Dick Lowry. After capturing Raphael Argus, a notorious assassin who began his career on Altair V, Buck learns that the killer is to attend a conclave of terrorists. Buck assumes his identity, discovers a plot to destroy New Chicago, is himself discovered, and manages to get back to Earth to foil the conspiracy. Certain of the participants in the terror summit began their criminal careers on Rigel IV.

- BraveStarr (1987–1988), animated television series produced by Lou Scheimer. Handlebar is a hulking, 14-ton, green-skinned bartender and former space pirate from the Rigel star system, with a bright orange handlebar mustache and a Brooklyn accent. He mostly serves BraveStarr and Thirty Thirty a drink called "sweetwater" in his bar, as they sit and discuss the moral lesson learned in that day's episode.

- "Hungry are the Damned" (1990), second scary tale in the Treehouse of Horror special halloween episode of Season 2 of The Simpsons, written and directed by the series' extended team. The Simpsons are abducted from a backyard barbecue by Kang and Kodos, horrific cyclopean denizens of Rigel VII, who appear to be fattening them up with sumptuous meals while conducting them back to their home planet in the Rigel system. By "an astonishing coincidence," the Rigelian tongue is identical to English. Given this opportunity for communication, Lisa confronts them with a book she has found on board whose dust-obscured title becomes elucidated piecemeal in a sequence of ominous/reassuring reveals, upon which the disgusted aliens return the Simpsons home. See also the episodes "'Scuse Me While I Miss the Sky" and "Simpson Tide" (paying homage to Rigel VII, from Star Trek, qv).[26]

- Justice League (2001–2004), animated television series created by Bruce Timm and Paul Dini. John Stewart, the phenotype of the Green Lantern in this series, puts down an uprising on the planet Rigel IX, but assures justice for all involved.

- Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer (2007), film written by Don Payne and Mark Frost, and directed by Tim Story. The Earth suffers a series of cosmic disasters at the hands of the Silver Surfer, harbinger of Galactus, a massive cloud-like cosmic entity which feeds on life-bearing planets to survive. Galactus has just consumed the planet Rigel III, and our world is next. In the climax of the film the Surfer sides with humanity and attacks his master, who is ultimately engulfed in a cosmic rift. The Silver one is himself killed in the battle ... or is he?

Comics

- Thor #131 (1966), issue in the Marvel Comics universe created by Stan Lee et al. The Rigellians, natives of Rigel III and also known as the Colonizers of Rigel, are a scientifically, technologically, and mentally advanced alien race bent on establishing the most powerful interplanetary empire in the galaxy through a program of remorseless colonization. The Rigellians make their first appearance in their true forms in this Marvel Comics issue, in which Thor extracts a promise that they will pass over the Earth if he is able to defeat their archenemy, Ego the Living Planet. Several years later, Rigel-3 is destroyed by the extra-galactic threat known as the Black Stars but not before its nine billion inhabitants flee aboard an evacuation fleet of gigantic starships.[27]

- Bucky O'Hare (1984– ), comic series created by Larry Hama and Michael Golden. The series is set in a parallel universe (the aniverse), where there is war between the inept but fundamentally decent United Animals Federation (run by mammals) and the sinister Toad Empire, which is ruled by a vast and manipulative computer system, KOMPLEX. Rigel is the home system of a race of anthropomorphic koalas.

- The Transformers (1984–1991), Marvel comics series written by Bob Budiansky and Simon Furman. In this series Rorza the Rocket-Cycle rider is a native of Rigel III.

- Monty (1985– ), comic strip created and written by Jim Meddick. Monty's alien friend Dave-7 (formerly Mr. Pi) is an extraterrestrial from Rigel who functions as a "straight man" to the protagonist. Cohabiting with Monty, Dave-7 is unemotionally logical and spends his time studying abstruse disciplines such as quantum mechanics. The strip contains occasionally ominous references to the plans of the Rigelians take over the Earth but nothing ever comes of them—the hapless would-be conquerors simply cannot manage such a grandiose scheme.

Games

- Rescue at Rigel (1980), computer game developed and published by Epyx. A player takes on the role of adventurer Sudden Smith. Smith must try to rescue human captives from the interior of an asteroid orbiting the star Rigel. Players have 60 minutes to rescue 10 captives from the labyrinthine body, all the while defeating or evading a variety of exotic alien enemies.

- Rigel's Revenge (1987), text-interface video game designed by Ron Harris and published by Mastertronic. Players assume the roles of two investigators on a mission to the planet Rigel V in rebellion against the Federation of Planets. The Rigellians claim to possess a doomsday machine which will exact a terrible revenge if the Federation refuses to withdraw immediately from their world. Will the players discover the infernal device before it's too late? Will the galaxy be saved?

- Star Control II (1992), computer game developed by Toys for Bob and published by Accolade. Beta Orionis I is the homeworld of the Umgah, large pink or lilac blobs who are born agoraphobes and cruel practical jokers. In the game, Rigel is not the same star at all, and is quite distant from the constellation Orion. Players of the game who explore "Rigel" experience an encounter with an emissary from the Zoq-Fot-Pik, an equally "interesting"[28] group of races who in ancient days discovered the wheel, fire, and religion all on the same day, and who revere the faux-sport "Frungy".

- Duke Nukem II (1993), computer game designed by Todd Replogle et al. and published by Apogee Software. In the year 1998 the evil Rigelatins plan to enslave Earth, and they kidnap Duke Nukem (even as he is promoting his new autobiography Why I'm So Great), because they plan to exploit his brain to put together an unbeatable attack strategy against humanity. Duke breaks free to save the world, again.

- Frontier: Elite II (1993) and Frontier: First Encounters (1995), computer games written by David Braben et al. Rigel is the primary star of a distant, uninhabited planetary system.

- Escape Velocity (1996), computer game by Ambrosia Software. Rigel is a central strategic node for the Confederacy in its battle against the Rebellion. In the Escape Velocity universe, Rigel and Sirius are located the same distance from the Earth. In reality, the situation is quite different: Rigel is between 700 and 900 light-years distant, while Sirius is a mere 8.6 light-years away.

- Pardus (2004), Web-browser based MMORPG developed and published by the Austrian company Bayer&Szell OG. Rigel is a Homeworld sector in the Pardus Empire Contingent (see graphic). The game is set in a technologically advanced but war-torn future universe. Players begin the game with a low-end spacecraft and attempt to increase their wealth, rank, skills and otherwise advance their characters. They may optionally join factions, syndicates or contingents for rank-based rewards, or they may choose to build their wealth by developing trade routes or constructing buildings or starbases that produce commodities.

See also

Rigel is referred to as a location in space or the center of a planetary system unusually often in fiction. For a list containing many stars and planetary systems that have a less extensive list of references, see Stars and planetary systems in fiction.

For other fictional uses not directly connected with the star, see Rigel (disambiguation).

Notes and references

Notes

- ↑ Compare the alternate Arabic derivation riǧl al-ǧabbār of the name Rigel to the cognomen of the famous basketball player: Kareem (generous) Abdul (servant of) Jabbar (the great one), and also to the Bene Gesserit poison needle gom jabbar (the high-handed enemy) in Dune by Frank Herbert.[4]

- ↑ Rigel can be seen in the mornings from August until October and in the evenings from November until January. It would not have been visible on a September evening as Hemingway has it.

- ↑ Bester wrote this book in 1956. The modern-day values of Rigel's distance from the Earth and its luminosity are 860 ± 80 ly (not 540 ly) and 85,000 times that of the Sun (not 10,000).[10][11]

- ↑ Compare this with the plot of the 1979 anime film Galaxy Express 999 wherein the young hero Tetsuro receives an unlimited-use travel pass on the 999 galactic railroad from his mysterious female companion Maytel.

References

- 1 2 Przybilla, N; et al. (January 2006). "Quantitative spectroscopy of BA-type supergiants". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 445 (3): 1099–1126. arXiv:astro-ph/0509669

. Bibcode:2006A&A...445.1099P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053832.

. Bibcode:2006A&A...445.1099P. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20053832. - ↑ Burnham, Robert, Jr (1978). Burnham's Celestial Handbook. 3. New York: Dover Books. p. 1300. ISBN 0-486-23673-0.

- ↑ Schneider, Jean. "Interactive Extra-solar Planets Catalog". The Extrasolar Planets Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2012-03-11.

- ↑ Herbert, Frank (1965). Dune. New York: Ace Books. pp. 523–541 (glossary).

- ↑ Melville, Herman (2010). Mardi: and A Voyage Thither. 2. New York: Qontro Classic Books. p. 197. ASIN B003VTZ6OC.

- ↑ "Clarel/Part 4/Canto 16". Wikisource. pp. [etext: search on quotation]. Retrieved 2012-04-09.

- ↑ Wallace, Lew (2011). Ben-Hur. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace. p. 198. ISBN 1-4663-4816-X.

- ↑ Hemingway, Ernest (2007). The Old Man and the Sea. New York: Heritage Publishers. p. 59. ISBN 81-7026-229-1.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Smith, E E". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. pp. 1123–1124. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ van Leeuwen, F (November 2007). "Validation of the new Hipparcos reduction". Astronomy and Astrophysics. 474 (2): 653–664. arXiv:0708.1752

. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357.

. Bibcode:2007A&A...474..653V. doi:10.1051/0004-6361:20078357. - ↑ Kaler, James B. "Rigel". JAMES B. (JIM) KALER/Professor Emeritus of Astronomy, University of Illinois. Retrieved 2012-03-12.

- ↑ Bester, Alfred (1967). Tiger! Tiger!. Middlesex, England: Penguin Books. pp. 246–247.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Bester, Alfred". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. pp. 113–114. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Russell, Eric Frank (2007). Next of Kin. London: Pollinger in Print. p. 49. ISBN 978-1-905665-46-4.

- ↑ Reynolds, Mack (2011). Adaptation. Scotts Valley, CA: CreateSpace. p. 6. ISBN 1-4662-0043-X.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Reynolds, Mack". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 1006. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). The Star King. 22. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 58. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). The Demon Princes. 22–26. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. pp. passim. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). The Killing Machine. 23. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 79. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Vance, Jack (2005). Star King. 22. Multiple editors. Oakland, CA: The Vance Integral Edition. p. 70. ISBN 0-9712375-1-4.

- ↑ Clute, John; Nicholls, Peter (1993). "Planetary Romance". The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction. New York: St Martin's Griffin. p. 935. ISBN 0-312-13486-X.

- ↑ Adams, Douglas (2002). The Hitchhiker's Guide to the Galaxy. New York: Del Rey Books. p. 218. ISBN 0-345-45374-3.

- ↑ "Earth". Nine Planets. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ↑ Task Group on Astronomical Designations. "Naming Astronomical Objects/Naming Objects outside the Solar System". International Astronomical Union. Retrieved 2012-03-15.

- ↑ Johnson, Shane (1989). Worlds of the Federation. New York: Pocket Books. p. 36. ISBN 0-671-70813-9.

- ↑ Groening, Matt (1997). Richmond, Ray; Coffman, Antonia, eds. The Simpsons: A Complete Guide to Our Favorite Family (1st ed.). New York: HarperPerennial. ISBN 0-06-095252-0. LCCN 98141857. OCLC 37796735. OL 433519M.. pp. 36–37.

- ↑ Thor #218 (1973)

- ↑ Kasavin, Greg. "The Greatest Games of All Time". GameSpot. Retrieved 2012-04-07.