Herman Melville

| Herman Melville | |

|---|---|

Herman Melville, 1870. Oil painting by Joseph Oriel Eaton. | |

| Born |

Herman Melvill August 1, 1819 New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Died |

September 28, 1891 (aged 72) New York City, New York, U.S. |

| Occupation | Novelist, short story writer, teacher, sailor, lecturer, poet, customs inspector |

| Genre | Travelogue, Captivity narrative, Sea story, Gothic Romanticism, Allegory, Tall tale |

| Literary movement | Romanticism |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Knapp Shaw (1822–1906) (m. 1847) |

| Children |

|

|

| |

| Signature |

|

Herman Melville[lower-alpha 1] (August 1, 1819 – September 28, 1891) was an American novelist, short story writer, and poet of the American Renaissance period. His best known works include Typee (1846), a romantic account of his experiences in Polynesian life, and his whaling novel Moby-Dick (1851). His work was almost forgotten during his last thirty years. His writing draws on his experience at sea as a common sailor, exploration of literature and philosophy, and engagement in the contradictions of American society in a period of rapid change. He developed a complex, baroque style: the vocabulary is rich and original, a strong sense of rhythm infuses the elaborate sentences, the imagery is often mystical or ironic, and the abundance of allusion extends to Scripture, myth, philosophy, literature, and the visual arts.

Born in New York City as the third child of a merchant in French dry goods, Melville's formal education ended abruptly after his father died in 1832, leaving the family in financial straits. Melville briefly became a schoolteacher before he took to sea in 1839 as a common sailor on a merchant ship. In 1840 he signed aboard the whaler Acushnet for his first whaling voyage, but jumped ship in the Marquesas Islands. After further adventures, he returned to Boston in 1844. His first book, Typee (1845), a highly romanticized account of his life among Polynesians, became such a best-seller that he worked up a sequel, Omoo (1847). These successes encouraged him to marry Elizabeth Shaw, of a prominent Boston family, but were hard to sustain. His first novel not based on his own experiences, Mardi (1849), is a sea narrative that develops into a philosophical allegory, but was not well received. Redburn (1849), a story of life on a merchant ship, and his 1850 expose of harsh life aboard a Man-of-War, White-Jacket yielded warmer reviews but not financial security.

In August 1850, Melville moved his growing family to Arrowhead, a farm near Pittsfield, Massachusetts, where he established a profound but short-lived friendship with Nathaniel Hawthorne, to whom he dedicated Moby-Dick. Moby-Dick was another commercial failure, published to mixed reviews. Melville's career as a popular author effectively ended with the cool reception of Pierre (1852), in part a satirical portrait of the literary scene. His Revolutionary War novel Israel Potter appeared in 1855. From 1853 to 1856, Melville published short fiction in magazines, most notably "Bartleby, the Scrivener" (1853), "The Encantadas" (1854), and "Benito Cereno" (1855). These and three other stories were collected in 1856 as The Piazza Tales. In 1857, he voyaged to England, where he reunited with Hawthorne for the first time since 1852, and then went on to tour the Near East. The Confidence-Man (1857), was the last prose work he published during his lifetime. He moved to New York to take a position as Customs Inspector and turned to poetry. Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) was his poetic reflection on the moral questions of the Civil War. In 1867 his oldest child, Malcolm, died at home from a self-inflicted gunshot. Clarel: A Poem and Pilgrimage in the Holy Land, a metaphysical epic, appeared in 1876. In 1886, his second son, Stanwix, died and Melville retired. During his last years, he privately published two volumes of poetry, left one volume unpublished, and returned to prose of the sea: the novella Billy Budd, left unfinished at his death, was published in 1924.

Melville's death from cardiovascular disease in 1891 subdued a reviving interest in his work. The 1919 centennial of his birth became the starting point of the "Melville Revival". Critics discovered his work, scholars explored his life, his major novels and stories have become world classics, and his poetry has gradually attracted respect.

Biography

Early life

Born Herman Melvill in New York City on August 1, 1819,[1] to Allan Melvill (1782–1832)[2] and Maria (Gansevoort) Melvill (1791–1872), Herman was the third of eight children. His siblings, who played important roles in his career as well as his emotional life, were Gansevoort (1815–1846), Helen Maria (1817–1888), Augusta (1821–1876), Allan (1823–1872), Catherine (1825–1905), Frances Priscilla (1827–1885), and Thomas (1830–1884), who eventually became a governor of Sailors Snug Harbor. Part of a well-established and colorful Boston family, Melville's father spent much time out of New York and in Europe as a commission merchant and an importer of French dry goods.[3]

Both of Melville's grandfathers were heroes of the Revolutionary War. Major Thomas Melvill (1751–1832) had taken part in the Boston Tea Party,[4] and his maternal grandfather, General Peter Gansevoort (1749–1812), was famous for having commanded the defense of Fort Stanwix in New York in 1777.[5] Melville found satisfaction in his "double revolutionary descent".[6] Major Melvill sent his son Allan not to college but to France at the turn of the nineteenth century, where he spent two years in Paris and learned to speak and write French fluently.[7] He subscribed to his father's Unitarianism. In 1814, Allan married Maria Gansevoort Melvill, who was committed to the Dutch Reformed version of the Calvinist creed of her family. The severe Protestantism of the Gansevoort's tradition ensured that she knew her Bible well, in English as well as in Dutch,[lower-alpha 2] the language she had grown up speaking with her parents.[8]

Almost three weeks after his birth, on August 19, Herman Melville was baptized at home by a minister of the South Reformed Dutch Church.[9] During the 1820s, Melville lived a privileged, opulent life, in a household with three or more servants at a time.[10] Once every four years, the family moved to more spacious and prestigious quarters, all the way to Broadway in 1828.[11] Allan Melvill lived beyond his means and on large sums he borrowed from both his father and his wife's widowed mother. His wife's opinion of his financial conduct is unknown. Biographer Hershel Parker suggests Maria "thought her mother's money was infinite and that she was entitled to much of her portion now, while she had small children".[11] How well, biographer Delbanco adds, the parents managed to hide the truth from their children is "impossible to know".[12] In 1830, Maria's family finally lost patience and their support came to a halt, at which point Allan's total debt to both families exceeded $20,000.[13] The felicity of Melville's early childhood, biographer Newton Arvin writes, depended not so much on wealth as on the "exceptionally tender and affectionate spirit in all the family relationships, especially in the immediate circle. "[14] Arvin describes Allan as "a man of real sensibility and a particularly warm and loving father", while Maria was "warmly maternal, simple, robust, and affectionately devoted to her husband and her brood."[14]

Melville's education began when he was five, around the time the Melvills moved to a newly-built house at 33 Bleecker Street.[15] In 1826, the same year that Melville contracted scarlet fever, Allan Melvill, who sent both Gansevoort and Herman to the New York Male High School, described Melville in a letter to Peter Gansevoort Jr. as "very backwards in speech & somewhat slow in comprehension".[16][17] His older brother Gansevoort appeared to be the brightest of the children, but soon Melville's development increased its pace. "You will be as much surprised as myself to know", Allan wrote Peter Gansevoort Jr., "that Herman proved the best Speaker in the introductory Department, at the examination of the High School, he has made rapid progress during the 2 last quarters."[18][19] In 1829, both Gansevoort and Herman were transferred to Columbia Grammar & Preparatory School, with Herman enrolling in the English Department on 28 September.[18] "Herman I think is making more progress than formerly", Allan wrote in May 1830 to Major Melvill, "& without being a bright Scholar, he maintains a respectable standing, & would proceed further, if he could only be induced to study more – being a most amiable & innocent child, I cannot find it in my heart to coerce him."[20]

Emotionally unstable and behind with paying the rent for the house on Broadway, Allan tried to recover from his setbacks by moving his family to Albany in 1830 and going into the fur business.[21] Melville attended the Albany Academy from October 1830 to October 1831, where he took the standard preparatory course, studying reading and spelling; penmanship; arithmetic; English grammar; geography; natural history; universal, Greek, Roman and English history; classical biography; and Jewish antiquities.[22] It is unknown why he left the Academy in October 1831; Parker suggests that by then "even the tiny tuition fee seemed too much to pay".[23] His brothers Gansevoort and Allan continued their attendance a few months longer, Gansevoort until March the next year.[23] "The ubiquitous classical references in Melville's published writings," as Melville scholar Merton Sealts observed, "suggest that his study of ancient history, biography, and literature during his school days left a lasting impression on both his thought and his art, as did his almost encyclopedic knowledge of both the Old and the New Testaments".[24]

In December, Melville's father returned from New York City by steamboat, but ice forced him to travel the last seventy miles for two days and two nights in an open horse carriage at two degrees below zero, with the result that he developed a cold.[25] In early January, he began to show "signs of delirium"[26] and his situation grew worse until he – in the words of his wife – "by reason of severe suffering was deprive'd of his Intellect".[27] Two months before reaching fifty, Allan Melville died on 28 January 1832.[28] Since Melville was no longer attending school, he must have witnessed these scenes: twenty years later he described such a death of Pierre's father in Pierre.[29]

1832–1838: After father's death

One result of his father's early death was that the religious creed of his mother exerted more influence. Melville's saturation in orthodox Calvinism is for Arvin "surely the most decisive intellectual and spiritual influence of his early life".[30] Two months after his father's death, Gansevoort entered the cap and fur business. Maria sought consolation in her faith and in April was admitted as a member of the First Reformed Dutch Church. Uncle Peter Gansevoort, who was one of the directors of the New York State Bank, got Herman a job as clerk for $150 a year.[31] The issue of his emotional response to all the drama in his young life is a question biographers answer by citing from Redburn: "I had learned to think much and bitterly before my time", the narrator remarks, adding, "I must not think of those delightful days, before my father became a bankrupt ... and we removed from the city; for when I think of those days, something rises up in my throat and almost strangles me."[12][31] According to Arvin's influential suggestion, with Melville, one has to reckon with the "tormented psychology, of the decayed patrician."[30]

When Melville's grandfather died on September 16, 1832, it turned out that Allan had borrowed more than his share of the inheritance. He left Maria Melville only $20.[32] The grandmother died on April 12, 1833.[33] Melville did his job well at the bank; though he was only fourteen in 1834, the bank considered him competent enough to be sent to Schenectady on an errand. Not much else is known from this period, except that he was very fond of drawing.[34] The visual arts became a lifelong interest.

Around May 1834, the Melvilles moved to another house in Albany, a three-story brick house. That same month a fire destroyed Gansevoort's skin-preparing factory, which left him with personnel he could neither use nor afford. Instead he pulled Melville out of the bank to man the cap and fur store.[34] (Biographer Andrew Delbanco says that Gansevoort was doing so well he could hire his younger brother until a fire broke out in 1835, destroying both factory and the store.[35]) In any case, his older brother Gansevoort served as a role model for Melville in various ways. In early 1834 Gansevoort had become a member of the Albany's Young Men's Association for Mutual Improvement, and in January 1835 Melville became a member as well.[36]

In 1835, while still working in the store, Melville enrolled in Albany Classical School, perhaps using Maria's part of the proceeds from the sale of the estate of his maternal grandmother in March 1835.[37] In September of the following year Herman was back in Albany Academy, in the Latin course. He also joined debating societies, in an apparent effort to make up as much as he could for his missed years of schooling. In this period he also became acquainted with Shakespeare's Macbeth at least, and teased his sisters with a passage from the witch scenes.[38]

In March 1837, he was again withdrawn from Albany Academy. Gansevoort had copies of John Todd's Index Rerum, a blank book, more of a register, in which one could index remarkable passages from books one had read, for easy retrieval. Among the sample entries was "Pequot, beautiful description of the war with," with a short title reference to the place in Benjamin Trumbull's A Complete History of Connecticut (1797 or 1818) where the description could be found. The two surviving volumes are the best evidence for Melville's reading in this period, because there is little doubt that Gansevoort's reading served him as a guide. The entries include books that Melville later used for Moby-Dick and Clarel, such as "Parsees—of India—an excellent description of their character, & religion & an account of their descent—East India Sketch Book p. 21."[39] Other entries are on Panther, the pirate's cabin, and storm at sea from James Fenimore Cooper's The Red Rover, Saint-Saba.[40]

That April, the nationwide economic panic forced Gansevoort to file for bankruptcy and Uncle Thomas Jr. secretly planned to leave Pittsfield, where he had not paid taxes on the farm. On June 5 Maria informed the younger children that they had to move to some village where the rent was cheaper than in Albany. Gansevoort became a Law student in New York City and Herman took care of the farm while his uncle settled in Galena, Illinois. That summer Melville decided to become a schoolteacher. He got a position at Sikes District School near Lenox, Massachusetts, where he taught some thirty students of various ages, including his own.[41]

His term over, he returned to his mother in 1838. In February he was elected president of the Philo Logos Society, which Peter Gansevoort invited to move into Stanwix Hall for no rent. Many chambers were vacant as a result of the economic crisis. In March 1838 Melville published in the Albany Microscope two polemical letters about issues in the debating societies he was engaged in, but it is not entirely clear what the polemic was about. Biographers Leon Howard and Hershel Parker suggest that the real issue was the youthful desire to exercise his rhetoric skills in public, and the first appearance in print would have been an exciting experience for all young men involved.[42]

In May the Melvilles moved to Lansingburgh, almost 12 miles north of Albany, into a rented house on the east side of the river in what is now Troy, at 1st Avenue and 114th Street.[43] The family's retreat was now complete: from the metropolis to a provincial city to a village.[44] What Melville was doing after his term at Sikes ended until November, or if he even had a job after that, remains a mystery. Apparently he courted a local Lansingburgh girl sometime during the summer, but nothing else is known.[45]

On 7 November, Melville arrived in Lansingburgh. Where he had come from is unknown. Five days later he paid for a term at Lansingburgh Academy, where he took a course in surveying and engineering. In April 1839 Peter Gansevoort wrote a letter to get Herman a job in the Engineer Department of the Erie Canal, saying that his nephew "possesses the ambition to make himself useful in a business which he desires to make his profession," but no job resulted.[46]

Melville's first known published essay came only weeks after he failed to find a job as an engineer. Using the unexplained initials L.A.V., Herman contributed "Fragments from a Writing Desk" to the Democratic Press and Lansingburgh Advertiser, a weekly newspaper, which printed the piece in two installments, the first on 4 May.[47] According to scholar Sealts, the heavy-handed allusions reveal his early familiarity with the writings of William Shakespeare, John Milton, Walter Scott, Richard Brinsley Sheridan, Edmund Burke, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Lord Byron, and Thomas Moore, which Gansevoort had kept around the house.[48] Biographer Parker calls the piece "characteristic Melvillean mood-stuff," and considers its prose style "excessive enough to allow him to indulge his extravagances and just enough overdone to allow him to deny that he was taking his style seriously".[47] Biographer Delbanco finds the prose "overheated in the manner of Poe, with sexually charged echoes of Byron and The Arabian Nights".[49]

1839–1844: Years at sea

On May 31, 1839, Gansevoort, then living in New York City, wrote that he was sure Herman could get a job on a whaler or merchant vessel.[50] The next day, he signed aboard the merchant ship St. Lawrence as a "boy" (a green hand), which cruised from New York to Liverpool and arrived back in New York October 1.[51] Redburn: His First Voyage (1849) draws on his experiences in this journey. Melville resumed teaching, now at Greenbush, New York, but left after one term because he had not been paid. In the summer of 1840 he and his friend James Murdock Fly went to Galena, Illinois to see if his Uncle Thomas could help them find work. On this trip it is possible that Herman went up the Mississippi, where he may well have witnessed scenes of frontier life he later used in his books. Unsuccessful, he and his friend returned home in autumn, very likely by way of St. Louis and up the Ohio River.[52]

Probably inspired by his reading of Richard Henry Dana, Jr.'s new book Two Years Before the Mast, and by Jeremiah N. Reynolds's account in the May 1839 issue of The Knickerbocker magazine of the hunt for a great white sperm whale named Mocha Dick, Melville and Gansevoort traveled to New Bedford, where Melville signed up for a whaling voyage aboard a new ship, the Acushnet.[53] Built in 1840, the ship measured some 104 feet in length, almost 28 feet in breadth, and almost 14 feet in depth. She measured slightly less than 360 tons, had two decks and three masts, but no galleries.[54] Melville signed a contract on Christmas Day with the ship's agent as a "green hand" for 1/175th of whatever profits the voyage would yield. On Sunday the 27th the brothers heard the Reverend Enoch Mudge preach at the Seamen's Bethel on Johnny-Cake Hill, where white marble cenotaphs on the walls memorialized local sailors who had died at sea, often in battle with whales.[55] When he signed the crew list the next day he was advanced $84.[56]

On January 3, 1841, the Acushnet set sail.[57][lower-alpha 3] Melville slept with some twenty others in the forecastle; captain Valentine Pease, the mates, and the skilled men slept aft.[58] Whales were found near The Bahamas, and in March 150 barrels of oil were sent home from Rio de Janeiro. Cutting in and trying-out (boiling) a single whale took some three days, and a whale yielded approximately one barrel of oil per foot of length and per ton of weight (the average whale weighed 40 to 60 tons). The oil was kept on deck for a day to cool off, and was then stowed down; scrubbing the deck completed the labor. An average voyage meant that some forty whales were killed to yield some 1600 barrels of oil.[59]

On 15 April, the Acushnet sailed around Cape Horn, and traveled to the South Pacific, where the crew sighted whales without catching any. Then up the coast of Chile to the region of Selkirk Island and on 7 May, near Juan Fernández Islands, she had 160 barrels. On 23 June the ship anchored for the first time since Rio, in Santa Harbor.[60] The cruising grounds the Acushnet was sailing attracted much traffic, and captain Pease not only paused to visit other whalers, but at times hunted in company with them.[61] From 23 July into August the Acushnet regularly gamed with the Lima from Nantucket, and Melville met William Henry Chase, the son of Owen Chase, who gave him a copy of his father's account of his adventures aboard the Essex.[62] Ten years later Melville wrote in his other copy of the book: "The reading of this wondrous story upon the landless sea, & close to the very latitude of the shipwreck had a surprising effect upon me."[63]

On 25 September the ship reported 600 barrels of oil to another whaler, and in October 700 barrels.[lower-alpha 4] On 24 October the Acushnet crossed the equator to the north, and six or seven days later arrived at the Galápagos Islands. This short visit would be the basis for The Encantadas.[64] On 2 November, the Acushnet and three other American whalers were hunting together near the Galápagos Islands; Melville later exaggerated that number in Sketch Fourth of The Encantadas. From 19 to 25 November the ship anchored at Chatham's Isle,[65] and on 2 December reached the coast of Peru near Paita.[66]

On July 9, 1842, Melville and his ship-mate Richard Tobias Greene jumped ship at Nukahiva Bay in the Marquesas Islands and ventured into the mountains to avoid capture.[67] Melville's first book, Typee (1845), is loosely based on his stay in or near the Taipi Valley. Scholarly research starting in the 1930s and extending into the twenty-first century has increasingly shown that much if not all of this account was either taken from Melville’s readings or exaggerated to dramatize a contrast between idyllic native culture and Western civilization. [68]

On August 9, Melville boarded the Lucy Ann, bound for Tahiti, where he took part in a mutiny and was briefly jailed in the native Calabooza Beretanee.[67]

In October, he and crew mate John B. Troy escaped Tahiti for Eimeo.[51] He then spent a month as beachcomber and island rover ("omoo" in Tahitian), eventually crossing over to Moorea. He drew on these experiences for Omoo, the sequel to Typee In November, he signed articles on the Nantucket whaler Charles & Henry for a six-month cruise (November 1842 − April 1843), and was discharged at Lahina in the Hawaiian Islands in May 1843.[51][67] After four months of working several jobs, including as a clerk, he joined the US Navy initially as one of the crew of the frigate USS United States as an ordinary seaman on August 20.[67] During the next year, the homeward bound ship visited the Marquesas Islands, Tahiti, and Valparaiso, and then, from summer to fall 1844, Mazatlan, Lima, and Rio de Janeiro,[51] before reaching Boston on October 3.[67] Melville was discharged on October 14.[51] This navy experience is used in White-Jacket (1850) Melville's fifth book.[69]

Melville's wander-years created what biographer Arvin calls "a settled hatred of external authority, a lust for personal freedom" and a "growing and intensifying sense of his own exceptionalness as a person", along with "the resentful sense that circumstance and mankind together had already imposed their will upon him in a series of injurious ways."[70] Scholar Milder believes the encounter with the wide ocean, where he was seemingly abandoned by God, led Melville to experience a "metaphysical estrangement" and influenced his social views in two ways: First that he belonged to the genteel classes but sympathized with the "disinherited commons" he had been placed among; second that experiencing the cultures of Polynesia let him view the West from an outsider's perspective.[71]

1845–1850: Successful writer

Upon his return, Melville regaled his family and friends with his adventurous tales and romantic experiences, and they urged him to put them into writing. Melville completed Typee, his first book, in the summer of 1845 while living in Troy. His brother Gansevoort found a publisher for it in London, where it was published in February 1846 by John Murray and became an overnight bestseller, then in New York on March 17 by Wiley & Putnam.[67] Inspired by his adventures in the Marquesas, the book was far from a reliable autobiographical account. Melville extended the period his narrator spent on the island to three months more than he himself did, made it appear that he understood the native language, and incorporated material from source books he had assembled.[72] Scholar Robert Milder calls Typee "an appealing mixture of adventure, anecdote, ethnography, and social criticism presented with a genial latitudinarianism that gave novelty to a South Sea idyll at once erotically suggestive and romantically chaste".[71]

An unsigned review in the Salem Advertiser, actually written by Nathaniel Hawthorne, called the book a "skilfully managed" narrative, "lightly but vigorously written" by an author with "that freedom of view ... which renders him tolerant of codes of morals that may be little in accordance with our own". The depictions of the "native girls are voluptuously colored, yet not more so than the exigencies of the subject appear to require."[73] Pleased but slightly bemused by the adulation of his new public, Melville later complained in a letter to Nathaniel Hawthorne that he would "go down to posterity ... as a ‘man who lived among the cannibals'!" [74]

Some readers found it unbelievable, however. The book brought Melville into contact with his friend Greene again, Toby in the book, who wrote to the newspapers confirming Melville's account. The two corresponded until 1863, and sustained a bond for life: in his final years Melville "traced and successfully located his old friend."[75]

In March 1847, Omoo, a sequel to Typee, was published by Murray in London, and in May by Harper in New York.[67] Omoo is "a slighter but more professional book," according to Milder.[76] Typee and Omoo gave Melville overnight renown as a writer and adventurer, and he often entertained by telling stories to his admirers. As the writer and editor Nathaniel Parker Willis wrote, "With his cigar and his Spanish eyes, he talks Typee and Omoo, just as you find the flow of his delightful mind on paper".[77] In 1847 Melville tried unsuccessfully to find a "government job" in Washington.[67]

In June 1847, Melville and Elizabeth Knapp Shaw were engaged, after knowing each other for approximately three months. A brief courtship, yet Melville had already asked her father for her hand in March but was turned down.[78] Lizzie's father was Lemuel Shaw, the Chief Justice of the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court. Arvin describes Lemuel Shaw as a man "of an almost childlike tenderness of heart and gentleness of feeling". He had been an intimate friend of Melville's father, and had fallen in love with Allen's sister Nancy. He would have married her had she not died early. His grief was such that for many years he did not marry, and his friendship with the Melvilles continued after Allen's death.[79] His wife Elizabeth died when she gave birth to their first daughter, who was named Elizabeth in remembrance of her mother. Elizabeth was raised by her grandmother and the Irish nurse.[80] Arvin suggests that Melville's interest in Elizabeth may have been stimulated by "his need of Judge Shaw's paternal presence."[30] They were married on August 4, 1847.[67] As Lizzie wrote a relative, "my marriage was very unexpected, and scarcely thought of until about two months before it actually took place."[81] She wanted to be married in church, "but we all thought if it were to get about previously that 'Typee' was to be seen on such a day, a great crowd might rush out of mere curiosity to see 'the author' who would have no personal interest in us whatsoever, and make it very unpleasant for us both".[82] Because of Melville's celebrity status a private wedding ceremony took place at home. The couple honeymooned in Canada, and traveled to Montreal. They settled in a house on Fourth Avenue in New York City.

According to scholars Joyce Deveau Kennedy and Frederick James Kennedy, Lizzie brought the following qualities to their marriage: a sense of religious obligation in marriage, an intent to make a home with Melville regardless of place, a willingness to please her husband by performing such "tasks of drudgery" as mending stockings, an ability to hide her agitation, and a desire "to shield Melville from unpleasantness".[83] The Kennedys conclude their assessment with:

- If the ensuing years did bring regrets to Melville's life, it is impossible to believe he would have regretted marrying Elizabeth. In fact he must have realized that he could not have borne the weight of those years unaided--that without her loyalty, intelligence, and affection, his own wild imagination would have had no "port or haven."[84]

Biographer Robertson-Lorant's cites "Lizzie's adventurous spirit and abundant energy", and she suggests that "her pluck and good humor might have been what attracted Melville to her, and vice versa."[85] An example of such good humor appears in a letter about her not yet used to being married: "It seems sometimes exactly as if I were here for a visit. The illusion is quite dispelled however when Herman stalks into my room without even the ceremony of knocking, bringing me perhaps a button to sew on, or some equally romantic occupation."[86]

In March 1848, Mardi was published by Richard Bentley in London, and in April by Harper in New York.[67] Nathaniel Hawthorne thought it a rich book, he told Evert Augustus Duyckinck, a friend of Melville's, "with depths here and there that compel a man to swim for his life."[87] According to Robert Milder, the book began as another South Sea story but, as he wrote, Melville left that genre behind, first in favor of "a romance of the narrator Taji and the lost maiden Yillah", and then "to an allegorical voyage of the philosopher Babbalanja and his companions through the imaginary archipelago of Mardi".[76] On February 16, 1849, the Melvilles' first child, Malcolm, was born.[88]

In October 1849, Redburn was published by Bentley in London, and in November by Harper in New York.[67] The bankruptcy and death of Allan Melville, and Melville's own youthful humiliations surface in this "story of outward adaptation and inner impairment".[89] Biographer Robertson-Lorant regards the work as a deliberate attempt for popular appeal: "Melville modeled each episode almost systematically on every genre that was popular with some group of antebellum readers," combining elements of "the picaresque novel, the travelogue, the nautical adventure, the sentimental novel, the sensational French romance, the gothic thriller, temperance tracts, urban reform literature, and the English pastoral."[90]

In January 1850, White-Jacket was published by Bentley in London, and in March by Harper in New York.[67]

1850–1851: Hawthorne and Moby-Dick

In early May 1850 Melville wrote to fellow sea author Richard Henry Dana Jr. a letter that contains what is the earliest surviving mention of the writing of Moby-Dick, saying he was already "half way" done. In June he described the book to his English publisher as "a romance of adventure, founded upon certain wild legends in the Southern Sperm Whale Fisheries", and promised it would be done by the fall. The manuscript has not survived, so it is impossible to know its state at this critical juncture. Over the next several months, Melville radically transformed his initial plan, conceiving what Delbanco has described as "the most ambitious book ever conceived by an American writer".[91]

From August 4 to 12, the Melvilles and their neighbor Sarah Morewood, Evert Duyckinck, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and other literary figures from New York and Boston, came to Pittsfield to enjoy a period of social parties, picnics, dinners, and the like. On August 5, Nathaniel Hawthorne and his publisher James T. Fields joined the group, while Hawthorne's wife stayed at home to look after the children.[92] As the men took a stroll through Ice Glen, someone noticed that Hawthorne and Melville were absent, and the group went looking for the two, who were at last found "deep in conversation".[93] The following day, the group visited the Hawthornes, who since May were living in nearby Lenox. "I liked Melville so much", Hawthorne wrote to his friend Horatio Bridge, "that I have asked him to spend a few days with me", an uncharacteristic move for a man so attached to his work that he would not suffer overnight guests to keep him from it.[94] The following days, Melville wrote the essay "Hawthorne and His Mosses", a review of Hawthorne's Mosses from an Old Manse that appeared in two installments, on August 17 and 24, in The Literary World.[95]

Later that summer, Melville received a package from Duyckinck with a letter asking him to forward it to Hawthorne. When he delivered the package to Hawthorne, he did not know it contained his last three books. Hawthorne read them, as he wrote to Duyckinck on August 29, "with a progressive appreciation of their author". He liked the "unflinching" realism of Redburn and White-Jacket, and he thought Mardi was "a rich book, with depths here and there that compel a man to swim for his life", though he also noticed it could have been better if the author had taken more time.[96]

In September, Melville borrowed three thousand dollars from his father-in-law Lemuel Shaw to buy a 160-acre farm in Pittsfield. Melville called his new home Arrowhead because of the arrowheads that were dug up around the property during planting season.[97]

That winter, Melville on an impulse paid Hawthorne a visit, only to discover he was "not in the mood for company" as he was finishing The House of the Seven Gables. Hawthorne's wife Sophia entertained him while he waited for Hawthorne to come down for supper, and gave him copies of Twice-Told Tales and, for Malcolm, The Grandfather's Chair.[98] Melville invited them to visit Arrowhead some time in the next two weeks, and when Sophia agreed, he looked forward to "discussing the Universe with a bottle of brandy & cigars" with Hawthorne. A few days later Sophia notified the Melvilles that Hawthorne could not stop working on his new book for more than one day, and Melville felt moved to repeat his invitation: "Your bed is already made, & the wood marked for your fire."[99] Eventually Melville visited the Hawthornes again, and the next day Hawthorne surprised him by arriving at Arrowhead with his daughter Una. According to Robertson-Lorant, "The handsome Hawthorne made quite an impression on the Melville women, especially Augusta, who was a great fan of his books." They spent the day mostly "smoking and talking metaphysics".[100]

In Robertson-Lorant's assessment of the friendship, Melville was "infatuated with Hawthorne's intellect, captivated by his artistry, and charmed by his elusive personality," and though the two writers were "drawn together in an undeniable sympathy of soul and intellect, the friendship meant something different to each of them," with Hawthorne offering Melville "the kind of intellectual stimulation he needed". They may have been "natural allies and friends", yet they were also "fifteen years apart in age and temperamentally quite different", and Hawthorne "found Melville's manic intensity exhausting at times".[101]

Melville wrote ten letters to Hawthorne, "all of them effusive, profound, deeply affectionate".[102] Melville was inspired and encouraged by his new relationship with Hawthorne[103] during the period that he was writing Moby-Dick. He dedicated this new novel to Hawthorne, though their friendship was to wane only a short time later.[104]

On October 18, The Whale was published in Britain in three volumes, and on November 14 Moby-Dick appeared in the United States as a single volume. In between these dates, on October 22, 1851, the Melvilles' second child, Stanwix, was born.[105] On December 1 Hawthorne wrote a letter of appraisal to Duyckinck, prompted in part by his disagreement with the review in Literary World: "What a book Melville has written! It gives me an idea of much greater power than his preceding ones. It hardly seemed to me that the review of it, in the Literary World, did justice to its best points."[106]

In early December 1852, Melville visited the Hawthornes in Concord, and discussed the idea of the "Agatha" story which he had pitched to Hawthorne. This was the last known contact between the two writers before Melville visited Hawthorne in Liverpool four years later.[107]

1852–1857: Unsuccessful writer

Melville had high hopes that his next book would please the public and restore his finances. In April 1851 he wrote to his British publisher, Richard Bentley that his new book, "possessing unquestionable novelty" is "as I believe, very much more calculated for popularity than anything you have yet published of mine – being a regular romance, with a mysterious plot to it & stirring passions at work, and withall, representing a new & elevated aspect of American life... " [108] In fact, Pierre: or, The Ambiguities was heavily psychological, though drawing on the conventions of the romance, and difficult in style. It was not well received. The New York Day Book on September 8, 1852, published a venomous attack headlined "HERMAN MELVILLE CRAZY". The item, offered as a news story, reported,

A critical friend, who read Melville's last book, Ambiguities, between two steamboat accidents, told us that it appeared to be composed of the ravings and reveries of a madman. We were somewhat startled at the remark, but still more at learning, a few days after, that Melville was really supposed to be deranged, and that his friends were taking measures to place him under treatment. We hope one of the earliest precautions will be to keep him stringently secluded from pen and ink.[109]

On 22 May 1853, Elizabeth (Bessie) was born, the Melvilles' third child and first daughter, and on or about that day Herman finished work on Isle of the Cross—one relative wrote that 'The Isle of the Cross' is almost a twin sister of the little one ..." Herman traveled to New York to discuss it with his publisher, but later wrote that Harper & Brothers was "prevented" from publishing his manuscript, presumed to be Isle of the Cross, which has been lost.[110]

Finding it difficult to find a publisher for his follow-up novel to the commercial and critical failure of Pierre, Israel Potter, the narrative of a Revolutionary War veteran, was first serialized in Putnam's Monthly Magazine in 1853. From November 1853 to 1856, Melville published fourteen tales and sketches in Putnams and Harpers magazines. In December 1855 he proposed to Dix & Edwards, the new owners of Putnam's, that they publish a selection of the short fiction titled Benito Cereno and Other Sketches. The collection would eventually be named after a new introductory story Melville had written for it, "The Piazza," and was published as The Piazza Tales, with five previously published stories, including "Bartleby, the Scrivener" and "Benito Cereno".[111]

On March 2, 1855, Frances (Fanny) was born, the Melvilles' fourth child.[112] In this period his book Israel Potter was published.

The writing of The Confidence-Man put great strain on Melville, leading Sam Shaw, a nephew of Lizzie, to write to his uncle Lemuel Shaw, "Herman I hope has had no more of those ugly attacks"—a reference to what Robertson-Lorant calls "the bouts of rheumatism and sciatica that plagued Melville".[113] Melville's father-in-law apparently shared his daughter's "great anxiety about him" when he wrote a letter to a cousin, in which he described Melville's working habits: "When he is deeply engaged in one of his literary works, he confines him[self] to hard study many hours in the day, with little or no exercise, & this specially in winter for a great many days together. He probably thus overworks himself & brings on severe nervous affections."[114] Shaw advanced Melville $1,500 from Lizzie's inheritance to travel four or five months in Europe and the Holy Land.[113]

From October 11, 1856, to May 20, 1857,[115] Melville made a six-month Grand Tour of the British Isles and the Mediterranean. While in England, in November he spent three days with Hawthorne, who had taken an embassy position there. At the seaside village of Southport, amid the sand dunes where they had stopped to smoke cigars, they had a conversation which Hawthorne later described in his journal:

Melville, as he always does, began to reason of Providence and futurity, and of everything that lies beyond human ken, and informed me that he 'pretty much made up his mind to be annihilated'; but still he does not seem to rest in that anticipation; and, I think, will never rest until he gets hold of a definite belief. It is strange how he persists—and has persisted ever since I knew him, and probably long before—in wandering to-and-fro over these deserts, as dismal and monotonous as the sand hills amid which we were sitting. He can neither believe, nor be comfortable in his unbelief; and he is too honest and courageous not to try to do one or the other. If he were a religious man, he would be one of the most truly religious and reverential; he has a very high and noble nature, and better worth immortality than most of us.[116]

Melville's subsequent visit to the Holy Land inspired his epic poem Clarel.[117]

On April 1, 1857, Melville published his last full-length novel, The Confidence-Man. This novel, subtitled His Masquerade, has won general acclaim in modern times as a complex and mysterious exploration of issues of fraud and honesty, identity and masquerade. But, when it was published, it received reviews ranging from the bewildered to the denunciatory.[118]

1857–1876: Poet

To repair his faltering finances, Melville was advised by friends to enter what had proven to be, at least for others, a remunerative field: public lecturing. From late 1857 to 1860, he embarked upon three lecture tours,[115] and spoke at lyceums, chiefly on Roman statuary and sightseeing in Rome.[119] Melville's lectures, which mocked the pseudo-intellectualism of lyceum culture, were panned by contemporary audiences.[120]

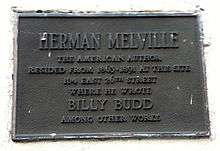

On May 30, 1860, Melville boarded the clipper Meteor for California, with his brother Thomas at the helm. After a shaky trip around Cape Horn Melville returned alone to New York via Panama in November. Turning to poetry, he submitted a collection of verse to a publisher in 1860, but it was not accepted. In 1861 he shook hands with Abraham Lincoln. In 1862, Melville met with a road accident which left him seriously injured. He also suffered from rheumatism.[121] In 1863 he bought his brother Allan's house at 104 East 26th Street in New York City and moved there. Allan for his part bought Arrowhead. On March 30 his father-in-law died.[122]

In 1864, Melville and Allan paid a visit to the Virginia battlefields of the American Civil War.[122] After the end of the war, he published Battle Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866), a collection of 72 poems that has been described as "a polyphonic verse journal of the conflict".[123] It was generally ignored by reviewers, who gave him at best patronizingly favorable reviews. The volume did not sell well; of the Harper & Bros. printing of 1200 copies, only 525 had been sold ten years later.[124] Uneven as a collection of individual poems, "its achievement lies in the interplay of voices and moods throughout which Melville patterns a shared historical experience into formative myth".[123]

In 1866, Melville's wife and her relatives used their influence to obtain a position for him as customs inspector for the City of New York, a humble but adequately paying appointment. He held the post for 19 years and won the reputation of being the only honest employee in a notoriously corrupt institution.[125] Unbeknownst to him, his modest position and income "were protected throughout the periodic turmoil of political reappointments by a customs official who never spoke to Melville but admired his writings: future US president Chester A. Arthur".[126] In 1867 his oldest son Malcolm shot himself, perhaps accidentally, and died at home at the age of 18. Some psychologists believe it was a suicide.[127]

The job came as a relief for his family, because he would be out of the house for much of the day. Melville suffered from unpredictable mood swings, habitually "bullying his servants, wife, and children."[128] As Robertson-Lorant's writes, "Like the tyrannical captains he had portrayed in his novels, Melville probably provoked rebellious feelings in his 'crew' by the capricious way he ruled the home, especially when he was drinking." Nervous exhaustion and physical pain rendered him short-tempered, made worse by his drinking. Robertson-Lorant takes the different ways one can look at Melville in this period to their extremes:

- An unsympathetic person might characterize Melville as a failed writer who held a low-level government job, drank too much, heckled his wife unmercifully about the housework, beat her occasionally, and drove the children to distraction with his unpredictable behavior. A sympathetic observer might characterize him as an underappreciated genius, a visionary, an iconoclastic thinker, a sensitive, orphaned American idealist, and a victim of a crude, materialistic society that ate artists and visionaries alive and spat out their bones. He was both, and more.[129]

In May 1867, Sam Shaw contacted Lizzie's minister Henry Bellows asking assistance with his "sister's case", which "has been a cause of anxiety to all of us for years past."[130] A wife then could not leave her husband without losing all claims to the children, so Bellows suggested Lizzie be kidnapped and brought to Boston. Shaw suspected that Lizzie would not agree to such melodramatic scheme. He thought up a different scheme, in which Lizzie would visit Boston and friends would inform Herman she would not come back. To get a divorce, she would then have to bring charges against Melville, believing her husband to be insane.[131]

In this period, Melville bought books on poetry, landscape, art, and engraving. By 1868, Melville owned a Rembrandt mezzotint which he had framed in New York.[132] In 1872 his brother Allan died,[132] as did his mother, aged eighty-two.[122] Though Melville's professional writing career had ended, he remained dedicated to his writing. Melville devoted years to "his autumnal masterpiece," an 18,000-line epic poem titled Clarel: A Poem and a Pilgrimage, inspired by his 1856 trip to the Holy Land.[133] His uncle, Peter Gansevoort, by a bequest, paid for the publication of the massive epic in 1876. The epic-length verse-narrative about a student's spiritual pilgrimage to the Holy Land, was considered quite obscure even in his own time. Among the longest single poems in American literature, the book had an initial printing of 350 copies, but sales failed miserably, and the unsold copies were burned when Melville was unable to afford to buy them at cost. The critic Lewis Mumford found a copy of the poem in the New York Public Library in 1925 "with its pages uncut"—in other words, it had sat there unread for 50 years.[134]

Clarel is a narrative in 18,000 verse lines, featuring a young American student of divinity as the title character. He travels to Jerusalem to renew his faith. One of the central characters, Rolfe, is similar to Melville in his younger days, a seeker and adventurer. Scholars also agree that the reclusive Vine is based on Hawthorne, who had died twelve years before.[133]

1877–1891: Final years

In 1884, Mrs. Melville received a legacy, which enabled her to allow Melville a monthly sum of $25 to spend on books and prints.[132] While Melville had his steady customs job, he no longer showed signs of depression, which recurred after the death of his second son. On 23 February 1886, Stanwix Melville died in San Francisco at age 36.[135] Melville retired on 31 December 1885,[122] after several of his wife's relatives died and left the couple more legacies which Mrs. Melville administered with skill and good fortune. In 1889 Melville becomes a member of the New York Society Library.[132]

As English readers, pursuing the vogue for sea stories represented by such writers as G. A. Henty, rediscovered Melville's novels in the late nineteenth century, the author had a modest revival of popularity in England, though not in the United States. He wrote a series of poems, with prose head notes, inspired by his early experiences at sea. He published them in two collections, each issued in a tiny edition of 25 copies for his relatives and friends. Of these, scholar Robert Milder calls John Marr and Other Poems (1888), "the finest of his late verse collections".[136] The second privately printed volume is Timoleon (1891).

Intrigued by one of these poems, Melville began to rework the headnote, expanding it first as a short story and eventually as a novella. He worked on it on and off for several years, but when he died in September 1891, the piece was unfinished. Also left unpublished were another volume of poetry, Weeds and Wildings, and a sketch, "Daniel Orme".[122] To Billy Budd, his widow added notes and edited it, but the manuscript was not discovered until 1919, by Raymond Weaver, his first biographer. He worked at transcribing and editing a full text, which he published in 1924 as Billy Budd, Sailor. It was an immediate critical success in England and soon one in the United States. The authoritative version was published in 1962, after two scholars studied the papers for several years. In 1951 it was adapted as a stage play on Broadway, and as an opera by English composer Benjamin Britten with assistance on the libretto by E. M. Forster. In 1961 Peter Ustinov released a movie based on the stage play and starring Terence Stamp.

Death

Melville died at his home in New York City early on the morning of September 28, 1891, at age 72. The doctor listed "cardiac dilation" on the death certificate.[137] He was interred in the Woodlawn Cemetery in The Bronx, New York City. A common story recounts that his New York Times obituary called him "Henry Melville," implying that he was unknown and unappreciated at his time of death, but the story is not true. A later article was published on October 6 in the same paper, referring to him as "the late Hiram Melville," but this appears to have been a typesetting error.[138]

Writing style

Melville's writing style shows enormous changes throughout the years as well as consistencies. In the words of Arvin, Melville's development "had been abnormally postponed, and when it came, it came with a rush and a force that had the menace of quick exhaustion in it."[79] As early a juvenile piece as "Fragments from a Writing Desk" from 1839, scholar Sealts points out, already shows "a number of elements that anticipate Melville's later writing, especially his characteristic habit of abundant literary allusion".[139] Typee and Omoo were documentary adventures that called for a division of the narrative in short chapters. Such compact organization bears the risk of fragmentation when applied to a lengthy work such as Mardi, but with Redburn and White Jacket, Melville turned the short chapter into an instrument of form and concentration.[140] A number of chapters of Moby-Dick are no longer than two pages in standard editions, and an extreme example is Chapter 122, consisting of a single paragraph of 36 words (including the thrice-repeated "Um, um, um.") The skillful handling of chapters in Moby-Dick is one of the most fully developed Melvillean signatures, and is a measure of "his manner of mastery as a writer".[141] Individual chapters have become "a touchstone for appreciation of Melville's art and for explanation" of his themes.[142] In contrast, the chapters in Pierre, called Books, are divided into short numbered sections, seemingly an "odd formal compromise" between Melville's natural length and his purpose to write a regular romance that called for longer chapters. As satirical elements were introduced, the chapter arrangement restores "some degree of organization and pace from the chaos".[141] The usual chapter unit then reappears for Israel Potter, The Confidence-Man and even Clarel, but only becomes "a vital part in the whole creative achievement" again in the juxtaposition of accents and of topics in Billy Budd.[141]

Newton Arvin points out that only superficially the books after Mardi seem as if Melville's writing went back to the vein of his first two books. In reality, his movement "was not a retrograde but a spiral one", and while Redburn and White-Jacket may lack the spontaneous, youthful charm of his first two books, they are "denser in substance, richer in feeling, tauter, more complex, more connotative in texture and imagery."[79] The rhythm of the prose in Omoo "achieves little more than easiness; the language is almost neutral and without idiosyncrasy", yet Redburn shows a "gain in rhythmical variety and intricacy, in sharpness of diction, in syntactical resource, in painterly bravura and the fusing of image and emotion into a unity of strangeness, beauty and dread".[79]

Melville's early works were "increasingly baroque"[143] in style, and with Moby-Dick Melville's vocabulary had grown superabundant. Bezanson calls it an "immensely varied style".[143] According to critic Warner Berthoff, three characteristic uses of language can be recognized. First, the exaggerated repetition of words, as in the series "pitiable," "pity," "pitied," and "piteous" (Ch. 81, "The Pequod Meets the Virgin"). A second typical device is the use of unusual adjective-noun combinations, as in "concentrating brow" and "immaculate manliness" (Ch. 26, "Knights and Squires").[144] A third characteristic is the presence of a participial modifier to emphasize and to reinforce the already established expectations of the reader, as the words "preluding" and "foreshadowing" ("so still and subdued and yet somehow preluding was all the scene ...," "In this foreshadowing interval ...").[145]

After his use of hyphenated compounds in Pierre, Melville's writing gives Berthoff the impression of becoming less exploratory and less provocative in his choices of words and phrases. Instead of providing a lead "into possible meanings and openings-out of the material in hand,"[146] the vocabulary now served "to crystallize governing impressions,"[146] the diction no longer attracted attention to itself, except as an effort at exact definition. The language, Berthoff continues, reflects a "controlling intelligence, of right judgment and completed understanding".[146] The sense of free inquiry and exploration which infused his earlier writing and accounted for its "rare force and expansiveness,"[147] tended to give way to "static enumeration."[148] For Berthoff, added "seriousness of consideration" came at the cost of losing "pace and momentum".[149] The verbal music and kinetic energy of Moby-Dick seem "relatively muted, even withheld" in the later works.[149]

Melville's paragraphing in his best work Berthoff considers to be the virtuous result of "compactness of form and free assembling of unanticipated further data", such as when the mysterious sperm whale is compared with Exodus's invisibility of God's face in the final paragraph of Chapter 86 ("The Tail").[150] Over time Melville's paragraphs became shorter as his sentences grew longer, until he arrived at the "one-sentence paragraphing characteristic of his later prose."[151] Berthoff points to the opening chapter of The Confidence-Man for an example, as it counts fifteen paragraphs, seven of which consist of only one elaborate sentence, and four that have only two sentences. The use of similar technique in Billy Budd contributes in large part, Berthoff says, to its "remarkable narrative economy".[152]

Verily I say unto you, It shall be more tolerable for the land of Sodom and Gomorrah in the day of judgment, than for that city.

—Matthew 10:15

I tell you it will be more tolerable for the Feegee that salted down a lean missionary in his cellar against a coming famine; it will be more tolerable for that provident Feegee, I say, in the day of judgment, than for thee, civilized and enlightened gourmand, who nailest geese to the ground and feastest on their bloated livers in thy paté-de-foie-gras.

— Melville paraphrases the Bible in "The Whale as a Dish", Moby-Dick Chapter 65

In Nathalia Wright's view, Melville's sentences generally have a looseness of structure, easy to use for devices as catalogue and allusion, parallel and refrain, proverb and allegory. The length of his clauses may vary greatly, but the "torterous" writing in Pierre and The Confidence-Man is there to convey feeling, not thought. Unlike Henry James, who was an innovator of sentence ordering to render the subtlest nuances in thought, Melville made few such innovations. His domain is the mainstream of English prose, with its rhythm and simplicity influenced by the King James Bible.[153]

Another important characteristic of Melville's writing style is in its echoes and overtones.[154] Melville's imitation of certain distinct styles is responsible for this. His three most important sources, in order, are the Bible, Shakespeare, and Milton.[155] Scholar Nathalia Wright has identified three stylistic categories of Biblical influence.[156] Direct quotation from any of the sources is slight; only one sixth of his Biblical allusions can be qualified as such.[157]

First, far more unmarked than acknowledged quotations occur, some favorites even numerous times throughout his whole body of work, taking on the nature of refrains. Examples of this idiom are the injunctions to be 'as wise as serpents and as harmless as doves,' 'death on a pale horse,' 'the man of sorrows', the 'many mansions of heaven;' proverbs 'as the hairs on our heads are numbered,' 'pride goes before a fall,' 'the wages of sin is death;' adverbs and pronouns as 'verily, whoso, forasmuch as; phrases as come to pass, children's children, the fat of the land, vanity of vanities, outer darkness, the apple of his eye, Ancient of Days, the rose of Sharon.'[158]

Second, there are paraphrases of individual and combined verses. Redburn's "Thou shalt not lay stripes upon these Roman citizens" makes use of language of the Ten Commandments in Ex.20,[lower-alpha 5] and Pierre's inquiry of Lucy: "Loveth she me with the love past all understanding?" combines John 21:15–17[lower-alpha 6] and Philippians 4:7[lower-alpha 7]

Third, certain Hebraisms are used, such as a succession of genitives ("all the waves of the billows of the seas of the boisterous mob"), the cognate accusative ("I dreamed a dream," "Liverpool was created with the Creation"), and the parallel ("Closer home does it go than a rammer; and fighting with steel is a play without ever an interlude").

A passage from Redburn (see quotebox) shows how all these different ways of alluding interlock and result in a fabric texture of Biblical language, though there is very little direct quotation.

The other world beyond this, which was longed for by the devout before Columbus' time, was found in the New; and the deep-sea land, that first struck these soundings, brought up the soil of Earth's Paradise. Not a Paradise then, or now; but to be made so at God's good pleasure,[lower-alpha 8] and in the fulness and mellowness of time.[lower-alpha 9] The seed is sown, and the harvest must come; and our children's children,[lower-alpha 10] on the world's jubilee morning, shall all go with their sickles to the reaping. Then shall the curse of Babel be revoked,[lower-alpha 11] a new Pentecost come, and the language they shall speak shall be the language of Britain.[lower-alpha 12] Frenchmen, and Danes, and Scots; and the dwellers on the shores of the Mediterranean,[lower-alpha 13] and in the regions round about;[lower-alpha 14] Italians, and Indians, and Moors; there shall appear unto them cloven tongues as of fire.[lower-alpha 15]

— The American melting pot described in Redburn's Biblical language, with Nathalia Wright's glosses.[159]

In addition to this, Melville successfully imitates three Biblical strains: he sustains the apocalyptic for a whole chapter of Mardi; the prophetic strain is expressed in Moby-Dick, most notably in Father Mapple's sermon; and the tradition of the Psalms is imitated at length in The Confidence-Man.

Melville owned an edition of Shakespeare's works by 1849, and his reading of it greatly influenced the style of his next book, Moby-Dick (1851). The critic F. O. Matthiessen found that the language of Shakespeare far surpasses other influences upon the book, in that it inspired Melville to discover his own full strength.[160] On almost every page, debts to Shakespeare can be discovered. The "mere sounds, full of Leviathanism, but signifying nothing" at the end of "Cetology" (Ch.32) echo the famous phrase in Macbeth: "Told by an idiot, full of sound and fury, Signifying nothing."[160] Ahab's first extended speech to the crew, in the "Quarter-Deck" (Ch.36) is practically blank verse and so is Ahab's soliloquy at the beginning of "Sunset" (Ch.37):'I leave a white and turbid wake;/ Pale waters, paler cheeks, where'er I sail./ The envious billows sidelong swell to whelm/ My track; let them; but first I pass.'[161] Through Shakespeare, Melville infused Moby-Dick with a power of expression he had not previously possessed.[162] Reading Shakespeare had been "a catalytic agent"[163] for Melville, one that transformed his writing from merely reporting to "the expression of profound natural forces."[163] The extent to which Melville assimilated Shakespeare is evident in the description of Ahab, Matthiessen continues, which ends in language that seems Shakespearean yet is no imitation: 'Oh, Ahab! what shall be grand in thee, it must needs be plucked from the skies and dived for in the deep, and featured in the unbodied air!' The imaginative richness of the final phrase seems particularly Shakespearean, "but its two key words appear only once each in the plays...and to neither of these usages is Melville indebted for his fresh combination."[164] Melville's diction depended upon no source, and his prose is not based on anybody else's verse but on an awareness of "speech rhythm".[165]

Melville's mastering of Shakespeare, Matthiessen finds, supplied him with verbal resources that enabled him te create dramatic language through three essential techniques. First, the use of verbs of action creates a sense of movement and meaning. The effective tension caused by the contrast of "thou launchest navies of full-freighted worlds" and "there's that in here that still remains indifferent" in "The Candles" (Ch. 119) makes the last clause lead to a "compulsion to strike the breast," which suggests "how thoroughly the drama has come to inhere in the words;"[166] Second, Melville took advantage of the Shakespearean energy of verbal compounds, as in "full-freighted". Third, Melville employed the device of making one part of speech act as another - for example, 'earthquake' as an adjective, or turning an adjective into a noun, as in "placeless".[167]

Melville's style, in Nathalia Wright's analysis, seamlessly flows over into theme, because all these borrowings have an artistic purpose, which is to suggest an appearance "larger and more significant than life" for characters and themes that are in fact unremarkable.[168] The allusions suggest that beyond the world of appearances another world exists, one that influences this world, and where ultimate truth can be found. Moreover, the ancient background thus suggested for Melville's narratives – ancient allusions being next in number to the Biblical ones – invests them with a sense of timelessness.[168]

Critical response

Contemporary criticism

Melville was not financially successful as a writer, having earned just over $10,000 for his writing during his lifetime.[169] After his success with travelogues based on voyages to the South Seas and stories based on misadventures in the merchant marine and navy, Melville's popularity declined dramatically. By 1876, all of his books were out of print.[170] In the later years of his life and during the years after his death, he was recognized, if at all, as a minor figure in American literature.

Melville revival and Melville studies

The "Melville Revival" of the late 1910s and 1920s brought about a reassessment of his work. The centennial of his birth was in 1919. Carl Van Doren's 1917 article on Melville in a standard history of American literature was the start of renewed appreciation. Van Doren also encouraged Raymond Weaver, who wrote the author's first full-length biography, Herman Melville: Mariner and Mystic (1921). Discovering the unfinished manuscript of Billy Budd, among papers shown to him by Melville's granddaughter, Weaver edited it and published it in a new collected edition of Melville's works. Other works that helped fan the flames for Melville were Carl Van Doren's The American Novel (1921), D. H. Lawrence's Studies in Classic American Literature (1923), Carl Van Vechten's essay in The Double Dealer (1922), and Lewis Mumford's biography, Herman Melville: A Study of His Life and Vision (1929).[171]

Starting in the mid-1930s, the Yale University scholar Stanley Williams supervised more than a dozen dissertations on Melville that were eventually published as books. Where the first wave of Melville scholars focused on psychology, Williams' students were prominent in establishing Melville Studies as an academic field concerned with texts and manuscripts, tracing Melville's influences and borrowings (even plagiarism), and exploring archives and local publications.[172] Jay Leyda, known for his work in film, spent more than a decade gathering documents and records for the day by day Melville Log (1951). Led by Leyda, the second phase of the Melville Revival emphasized research. Its scholars tended to think that Weaver, Harvard psychologist Henry Murray, and Mumford favored Freudian interpretations which read Melville's fiction too literally as autobiography, exaggerated Melville’s suffering in the family, mistakenly inferred a homosexual attachment to Hawthorne, and saw a tragic withdrawal after the cold critical reception for his last prose works rather than a turn to poetry as a new and satisfying form.[173]

Other post-war studies, however, continued the broad imaginative and interpretive style. Charles Olson's Call Me Ishmael (1947) presented Ahab as a Shakespearean character, and Newton Arvin's critical biography, Herman Melville (1950) won the National Book Award for non-fiction in 1951. [173] [174]

Critical editions

In the 1960s, Northwestern University Press, in alliance with the Newberry Library and the Modern Language Association, launched a project to edit and published reliable critical texts of Melville's complete works, including unpublished poems, journals, and correspondence. The aim of the editors was to present a text "as close as possible to the author's intention as surviving evidence permits". The volumes have extensive appendices, including textual variants from each of the editions published in Melville's lifetime, an historical note on the publishing history and critical reception, and related documents. In many cases, it was not possible to establish a "definitive text", but the edition supplies all evidence available at the time. Since the texts were prepared with financial support from the United States Department of Education, no royalties are charged, and they have been widely reprinted.

The Melville Society

In 1945, The Melville Society was founded, a non-profit organisation dedicated to the study of Melville's life and works. Between 1969 and 2003 it published 125 issues of Melville Society Extracts, which are now freely available on the society's website. Since 1999 it publishes Leviathan: A Journal of Melville Studies, currently three issues a year, published by Johns Hopkins University Press.

Melville's poetry

Melville did not publish poetry until late in life, and his reputation as a poet was not high until late in the 20th century.

Melville, says recent literary critic Lawrence Buell, "is justly said to be nineteenth-century America’s leading poet after Whitman and Dickinson, yet his poetry remains largely unread even by many Melvillians." True, Buell concedes, even more than most Victorian poets, Melville turned to poetry as an "instrument of meditation rather than for the sake of melody or linguistic play." It is also true that he turned from fiction to poetry late in life. Yet he wrote twice as much poetry as Dickinson and probably as many lines as Whitman, and he wrote distinguished poetry for a quarter of a century, twice as long as his career publishing prose narratives. The three novels of the 1850s which Melville worked on most seriously to present his philosophical explorations, Moby-Dick, Pierre, and The Confidence Man, seem to make the step to philosophical poetry a natural one rather than simply a consequence of commercial failure.[175]

In 2000, the Melville scholar Elizabeth Renker wrote "a sea change in the reception of the poems is incipient".[176] Some critics now place him as the first modernist poet in the United States; others assert that his work more strongly suggests what today would be a postmodern view.[177] Henry Chapin wrote in an introduction to John Marr and Other Sailors (1888), a collection of Melville's late poetry, "Melville's loveable freshness of personality is everywhere in evidence, in the voice of a true poet".[178] The poet and novelist Robert Penn Warren was a leading champion of Melville as a great American poet. Warren issued a selection of Melville's poetry prefaced by an admiring critical essay. The poetry critic Helen Vendler remarked of Clarel : "What it cost Melville to write this poem makes us pause, reading it. Alone, it is enough to win him, as a poet, what he called 'the belated funeral flower of fame'".[179]

Gender studies

Melville's writings did not attract the attention of women's studies scholars of the 1970s and 1980s, though his preference for sea-going tales that involved almost only males has since then been of interest to scholars in men's studies and especially gay and queer studies.[180] Melville was remarkably open in his exploration of sexuality of all sorts. For example, Alvin Sandberg claimed that the short story "The Paradise of Bachelors and the Tartarus of Maids" offers "an exploration of impotency, a portrayal of a man retreating to an all-male childhood to avoid confrontation with sexual manhood," from which the narrator engages in "congenial" digressions in heterogeneity.[181] In line with this view, Warren Rosenberg argues the homosocial "Paradise of Bachelors" is shown to be "superficial and sterile".[182]

David Harley Serlin observes in the second half of Melville's diptych, "The Tartarus of Maids," the narrator gives voice to the oppressed women he observes:

As other scholars have noted, the "slave" image here has two clear connotations. One describes the exploitation of the women's physical labor, and the other describes the exploitation of the women's reproductive organs. Of course, as models of women's oppression, the two are clearly intertwined.[183]

In the end Serlin says that the narrator is never fully able to come to terms with the contrasting masculine and feminine modalities.

Issues of sexuality have been observed in other works as well. Rosenberg notes Taji, in Mardi, and the protagonist in Pierre "think they are saving young 'maidens in distress' (Yillah and Isabel) out of the purest of reasons but both are also conscious of a lurking sexual motive".[182] When Taji kills the old priest holding Yillah captive, he says,

[R]emorse smote me hard; and like lightning I asked myself whether the death deed I had done was sprung of virtuous motive, the rescuing of a captive from thrall, or whether beneath the pretense I had engaged in this fatal affray for some other selfish purpose, the companionship of a beautiful maid.[184]

In Pierre, the motive of the protagonist's sacrifice for Isabel is admitted: "womanly beauty and not womanly ugliness invited him to champion the right".[185] Rosenberg argues,

This awareness of a double motive haunts both books and ultimately destroys their protagonists who would not fully acknowledge the dark underside of their idealism. The epistemological quest and the transcendental quest for love and belief are consequently sullied by the erotic.[182]

Rosenberg says that Melville fully explores the theme of sexuality in his major epic poem, Clarel. When the narrator is separated from Ruth, with whom he has fallen in love, he is free to explore other sexual (and religious) possibilities before deciding at the end of the poem to participate in the ritualistic order represented by marriage. In the course of the poem, "he considers every form of sexual orientation – celibacy, homosexuality, hedonism, and heterosexuality – raising the same kinds of questions as when he considers Islam or Democracy".[182]

Some passages and sections of Melville's works demonstrate his willingness to address all forms of sexuality, including the homoerotic, in his works. Commonly noted examples from Moby-Dick are the "marriage bed" episode involving Ishmael and Queequeg, which is interpreted as male bonding; and the "Squeeze of the Hand" chapter, describing the camaraderie of sailors' extracting spermaceti from a dead whale.[186] Rosenberg notes that critics say that "Ahab's pursuit of the whale, which they suggest can be associated with the feminine in its shape, mystery, and in its naturalness, represents the ultimate fusion of the epistemological and sexual quest."[182] In addition, he notes that Billy Budd's physical attractiveness is described in quasi-feminine terms: "As the Handsome Sailor, Billy Budd's position aboard the seventy-four was something analogous to that of a rustic beauty transplanted from the provinces and brought into competition with the highborn dames of the court."[182]

Law and literature

Since the late 20th century, Billy Budd has become a central text in the field of legal scholarship known as law and literature. In the novel, Billy, a handsome and popular young sailor, is impressed from the merchant vessel Rights of Man to serve aboard H.M.S. Bellipotent in the late 1790s, during the war between Revolutionary France and Great Britain. He excites the enmity and hatred of the ship's master-at-arms, John Claggart. Claggart accuses Billy of phony charges of mutiny and other crimes, and the Captain, the Honorable Edward Fairfax Vere, brings them together for an informal inquiry. At this encounter, Billy is frustrated by his stammer, which prevents him from speaking, and strikes Claggart. The blow catches Claggart squarely on the forehead and, after a gasp or two, the master-at-arms dies.

Vere immediately convenes a court-martial, at which, after serving as sole witness and as Billy's de facto counsel, Vere urges the court to convict and sentence Billy to death. The trial is recounted in chapter 21, the longest chapter in the book. It has become the focus of scholarly controversy; was Captain Vere a good man trapped by bad law, or did he deliberately distort and misrepresent the applicable law to condemn Billy to death?[187]

Themes

As early as 1839, in the juvenile sketch "Fragments from a Writing Desk," Melville explores a problem which would reappear in the short stories "Bartleby" (1853) and "Benito Cereno" (1855): the impossibility to find common ground for mutual communication. The sketch centers on the protagonist and a mute lady, leading scholar Sealts to observe: "Melville's deep concern with expression and communication evidently began early in his career."[188] According to scholar Nathalia Wright, Melville's characters are all preoccupied by the same intense, superhuman and eternal quest for "the absolute amidst its relative manifestations,"[189] an enterprise central to the Melville canon: "All Melville's plots describe this pursuit, and all his themes represent the delicate and shifting relationship between its truth and its illusion."[189] It is not clear, however, what the moral and metaphysical implications of this quest are, because Melville did not distinguish between these two aspects.[189] Throughout his life Melville struggled with and gave shape to the same set of epistemological doubts and the metaphysical issues these doubts engendered. An obsession for the limits of knowledge led to the question of God's existence and nature, the indifference of the universe, and the problem of evil.[76]

Legacy and honors

In 1985, the New York City Herman Melville Society gathered at 104 East 26th Street to dedicate the intersection of Park Avenue south and 26th Street as Herman Melville Square. This is the street where Melville lived from 1863 to 1891 and where, among other works, he wrote Billy Budd.[190]

In 2010, a species of extinct giant sperm whale, Livyatan melvillei, was named in honor of Melville. The paleontologists who discovered the fossil were fans of Moby-Dick and dedicated their discovery to the author.[191][192]

Selected bibliography

- Typee: A Peep at Polynesian Life (1846)

- Omoo: A Narrative of Adventures in the South Seas (1847)

- Mardi: And a Voyage Thither (1849)

- Redburn: His First Voyage (1849)

- White-Jacket; or, The World in a Man-of-War (1850)

- Moby-Dick; or, The Whale (1851)

- Pierre: or, The Ambiguities (1852)

- Isle of the Cross (1853 unpublished, and now lost)

- "Bartleby, the Scrivener" (1853) (short story)

- The Encantadas, or Enchanted Isles (1854)

- "Benito Cereno" (1855)

- Israel Potter: His Fifty Years of Exile (1855)

- The Confidence-Man: His Masquerade (1857)

- Battle-Pieces and Aspects of the War (1866) (poetry collection)

- The Martyr (1866) one of poems in a collection, on the death of Lincoln