Mutagenesis

Mutagenesis /mjuːtəˈdʒɛnɪsɪs/ is a process by which the genetic information of an organism is changed in a stable manner, resulting in a mutation. It may occur spontaneously in nature, or as a result of exposure to mutagens. It can also be achieved experimentally using laboratory procedures. In nature mutagenesis can lead to cancer and various heritable diseases, but it is also a driving force of evolution. Mutagenesis as a science was developed based on work done by Hermann Muller, Charlotte Auerbach and J. M. Robson in the first half of the 20th century.[1]

Background

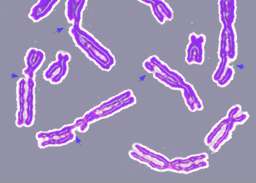

DNA may be modified, either naturally or artificially, by a number of physical, chemical and biological agents, resulting in mutations. In 1927, Hermann Muller first demonstrated that mutation with observable changes in the chromosomes can be caused by irradiating fruit flies with X-ray,[2] and lent support to the idea of mutation as the cause of cancer.[3] His contemporary Lewis Stadler also showed the mutational effect of X-ray on barley in 1928,[4] and ultraviolet (UV) radiation on maize in 1936.[5] In 1940s, Charlotte Auerbach and J. M. Robson, found that mustard gas can also cause mutations in fruit flies.[6]

While changes to the chromosome caused by X-ray and mustard gas were readily observable to the early researchers, other changes to the DNA induced by other mutagens were not so easily observable, and the mechanism may be complex and takes longer to unravel. For example, soot was suggested to be a cause of cancer as early as 1775,[7] and coal tar was demonstrated to cause cancer in 1915.[8] The chemicals involved in both were later shown to be polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAH).[9] PAHs by themselves are not carcinogenic, and it was proposed in 1950 that the carcinogenic forms of PAHs are the oxides produced as metabolites from cellular processes.[10] The metabolic process was identified in 1960s as catalysis by cytochrome P450 which produces reactive species that can interact with the DNA to form adducts,;[11][12] the mechanism by which the PAH adducts give rise to mutation, however, is still under investigation.

Mammalian nuclear DNA may sustain more than 60,000 damage episodes per cell per day, as listed with references in DNA damage (naturally occurring). If left uncorrected, these adducts, after misreplication past the damaged sites, can give rise to mutations. In nature, the mutations that arise may be beneficial or deleterious — this is the driving force of evolution. An organism may acquire new traits through genetic mutation, but mutation may also result in impaired function of the genes, and in severe cases, cause the death of the organism. In the laboratory, however, mutagenesis is a useful technique for generating mutations that allows the functions of genes and gene products to be examined in detail, producing proteins with improved characteristics or novel functions, as well as mutant strains with useful properties. Initially, the ability of radiation and chemical mutagens to cause mutation was exploited to generate random mutations, but later techniques were developed to introduce specific mutations.

The distinction between a mutation and DNA damage

DNA damage is an abnormal alteration in the structure of DNA that cannot, itself, be replicated when DNA replicates. In contrast, a mutation is a change in the nucleic acid sequence that can be replicated; hence, a mutation can be inherited from one generation to the next. Damage can occur from chemical addition (adduct), or structural disruption to a base of DNA (creating an abnormal nucleotide or nucleotide fragment), or a break in one or both DNA strands. When DNA containing damage is replicated, an incorrect base may be inserted in the new complementary strand as it is being synthesized (see DNA repair#Translesion synthesis). The incorrect insertion in the new strand will occur opposite the damaged site in the template strand, and this incorrect insertion can become a mutation (i.e. a changed base pair) in the next round of replication. Furthermore, double-strand breaks in DNA may be repaired by an inaccurate repair process, non-homologous end joining, which produces mutations. Mutations can ordinarily be avoided if accurate DNA repair systems recognize DNA damage and repair it prior to completion of the next round of replication. At least 169 enzymes are either directly employed in DNA repair or influence DNA repair processes.[13] Of these, 83 are directly employed in the 5 types of DNA repair processes indicated in the chart shown in the article DNA repair.

Mechanisms

Mutagenesis may occur endogenously, for example, through spontaneous hydrolysis, or through normal cellular processes that can generate reactive oxygen species and DNA adducts, or through error in replication and repair.[14] Mutagenesis may also arise as a result of the presence of environmental mutagens that induce changes to the DNA. The mechanism by which mutation arises varies according to the causative agent, the mutagen, involved. Most mutagens act either directly, or indirectly via mutagenic metabolites, on the DNA producing lesions. Some, however, may affect the replication or chromosomal partition mechanism, and other cellular processes.

Many chemical mutagens require biological activation to become mutagenic. An important group of enzymes involved in the generation of mutagenic metabolites is cytochrome P450.[15] Other enzymes that may also produce mutagenic metabolites include glutathione S-transferase and microsomal epoxide hydrolase. Mutagens that are not mutagenic by themselves but require biological activation are called promutagens.

Many mutations arise as a result of problems caused by DNA lesions during replication, resulting in errors in replication. In bacteria, extensive damage to DNA due to mutagens results in single-stranded DNA gaps during replication. This induces the SOS response, an emergency repair process that is also error-prone, thereby generating mutations. In mammalian cells, stalling of replication at damaged sites induces a number of rescue mechanisms that help bypass DNA lesions, but which also may result in errors. The Y family of DNA polymerases specializes in DNA lesion bypass in a process termed translesion synthesis (TLS) whereby these lesion-bypass polymerases replace the stalled high-fidelity replicative DNA polymerase, transit the lesion and extend the DNA until the lesion has been passed so that normal replication can resume. These processes may be error-prone or error-free.

Spontaneous hydrolysis

DNA is not entirely stable in aqueous solution. Under physiological conditions the glycosidic bond may be hydrolyzed spontaneously and 10,000 purine sites in DNA are estimated to be depurinated each day in a cell.[14] Numerous DNA repair pathways exist for DNA; however, if the apurinic site is not repaired, misincorporation of nucleotides may occur during replication. Adenine is preferentially incorporated by DNA polymerases in an apurinic site.

Cytidine may also become deaminated to uridine at one five-hundredth of the rate of depurination and can result in G to A transition. Eukaryotic cells also contain 5-methylcytosine, thought to be involved in the control of gene transcription, which can become deaminated into thymine.

Modification of bases

Bases may be modified endogenously by normal cellular molecules. For example, DNA may be methylated by S-adenosylmethionine, and glycosylated by reducing sugars.

Many compounds, such as PAHs, aromatic amines, aflatoxin and pyrrolizidine alkaloids, may form reactive oxygen species catalyzed by cytochrome P450. These metabolites form adducts with the DNA, which can cause errors in replication, and the bulky aromatic adducts may form stable intercalation between bases and block replication. The adducts may also induce conformational changes in the DNA. Some adducts may also result in the depurination of the DNA;[16] it is, however, uncertain how significant such depurination as caused by the adducts is in generating mutation.[17]

Alkylation and arylation of bases can cause errors in replication. Some alkylating agents such as N-Nitrosamines may require the catalytic reaction of cytochrome-P450 for the formation of a reactive alkyl cation. N7 and O6 of guanine and the N3 and N7 of adenine are most susceptible to attack. N7-guanine adducts form the bulk of DNA adducts, but they appear to be non-mutagenic. Alkylation at O6 of guanine, however, is harmful because excision repair of O6-adduct of guanine may be poor in some tissues such as the brain.[18] The O6 methylation of guanine can result in G to A transition, while O4-methylthymine can be mispaired with guanine. The type of the mutation generated, however, may be dependent on the size and type of the adduct as well as the DNA sequence.[19]

Ionizing radiation and reactive oxygen species often oxidize guanine to produce 8-oxoguanine.

DNA damage and spontaneous mutation

As noted above, the number of DNA damage episodes occurring in a mammalian cell per day is high (more than 60,000 per day). Frequent occurrence of DNA damage is likely a problem for all DNA- containing organisms, and the need to cope with DNA damage and minimize their deleterious effects is likely a fundamental problem for life.[20]

Most spontaneous mutations likely arise from error-prone trans-lesion synthesis past a DNA damage site in the template strand during DNA replication. This process can overcome potentially lethal blockages, but at the cost of introducing inaccuracies in daughter DNA. The causal relationship of DNA damage to spontaneous mutation is illustrated by aerobically growing E. coli bacteria, in which 89% of spontaneously occurring base substitution mutations are caused by reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced DNA damage.[21] In yeast, more than 60% of spontaneous single-base pair substitutions and deletions are likely caused by trans-lesion synthesis.[22]

An additional significant source of mutations in eukaryotes is the inaccurate DNA repair process non-homologous end joining, that is often employed in repair of double strand breaks.[23]

In general, it appears that the main underlying cause of spontaneous mutation is error prone trans-lesion synthesis during DNA replication and that the error-prone non-homologous end joining repair pathway may also be an important contributor in eukaryotes.

Crosslinking

Some alkylating agents may produce crosslinking of DNA. Some natural occurring chemicals may also promote crosslinking, such as psoralens after activation by UV radiation, and nitrous acid. Interstrand cross-linking is more damaging as it blocks replication and transcription and can cause chromosomal breakages and rearrangements. Some crosslinkers such as cyclophosphamide, mitomycin C and cisplatin are used as anticancer chemotherapeutic because of their high degree of toxicity to proliferating cells.

Dimerization

UV radiation promotes the formation of a cyclobutyl ring between adjacent thymines, resulting in the formation of pyrimidine dimers.[24] In human skin cells, thousands of dimers may be formed in a day due to normal exposure to sunlight. DNA polymerase η may help bypass these lesions in an error-free manner;[25] however, individuals with defective DNA repair function, such as sufferers of Xeroderma pigmentosum, are sensitive to sunlight and may be prone to skin cancer.

Intercalation between bases

The planar structure of chemicals such as ethidium bromide and proflavine allows them to insert between bases in DNA. This insert causes the DNA's backbone to stretch and makes slippage in DNA during replication more likely to occur since the bonding between the strands is made less stable by the stretching. Forward slippage will result in deletion mutation, while reverse slippage will result in an insertion mutation. Also, the intercalation into DNA of anthracyclines such as daunorubicin and doxorubicin interferes with the functioning of the enzyme topoisomerase II, blocking replication as well as causing mitotic homologous recombination.

Backbone damage

Ionizing radiation may produce highly reactive free radicals that can break the bonds in the DNA. Double-stranded breakages are especially damaging and hard to repair, producing translocation and deletion of part of a chromosome. Alkylating agents like mustard gas may also cause breakages in the DNA backbone. Oxidative stress may also generate highly reactive oxygen species that can damage DNA. Incorrect repair of other damage induced by the highly reactive species can also lead to mutations.

Insertional mutagenesis

Transposons and viruses may insert DNA sequence into coding regions or functional elements of a gene and result in inactivation of the gene.

Effects on replication and DNA repair

While most mutagens produce effects that ultimately result in errors in replication, for example creating adducts that interfere with replication, some mutagens may directly affect the replication process or reduce its fidelity. Base analog such as 5-bromouracil may substitute for thymine in replication. Metals such as cadmium, chromium, and nickel can increase mutagenesis in a number of ways in addition to direct DNA damage, for example reducing the ability to repair errors, as well as producing epigenetic changes.[26]

Mutagenesis as a laboratory technique

Mutagenesis in the laboratory is an important technique whereby DNA mutations are deliberately engineered to produce mutant genes, proteins, or strains of organism. Various constituents of a gene, such as its control elements and its gene product, may be mutated so that the functioning of a gene or protein can be examined in detail. The mutation may also produce mutant proteins with interesting properties, or enhanced or novel functions that may be of commercial use. Mutants strains may also be produced that have practical application or allow the molecular basis of particular cell function to be investigated.

Early methods of mutagenesis produced entirely random mutations; however, later methods of mutagenesis may produce site-specific mutation.

Types

See also

References

- ↑ Beale, G. (1993). "The Discovery of Mustard Gas Mutagenesis by Auerbach and Robson in 1941". Genetics. 134 (2): 393–399. PMC 1205483

. PMID 8325476.

. PMID 8325476. - ↑ Muller, H. J. (1927). "Artificial Transmutation of the Gene" (PDF). Science. 66 (1699): 84–87. doi:10.1126/science.66.1699.84. PMID 17802387.

- ↑ Crow, J. F.; Abrahamson, S. (1997). "Seventy Years Ago: Mutation Becomes Experimental". Genetics. 147 (4): 1491–1496. PMC 1208325

. PMID 9409815.

. PMID 9409815. - ↑ Stadler, L. J. (1928). "Mutations in Barley Induced by X-Rays and Radium". Science. 68 (1756): 186–187. doi:10.1126/science.68.1756.186. PMID 17774921.

- ↑ Stadler, L. J.; G. F. Sprague (1936-10-15). "Genetic Effects of Ultra-Violet Radiation in Maize. I. Unfiltered Radiation" (PDF). Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. US Department of Agriculture and Missouri Agricultural Experiment Station. 22 (10): 572–8. doi:10.1073/pnas.22.10.572. PMC 1076819

. PMID 16588111. Retrieved 2007-10-11.

. PMID 16588111. Retrieved 2007-10-11. - ↑ Auerbach, C.; Robson, J.M.; Carr, J.G. (March 1947). "Chemical Production of Mutations". Science. 105 (2723): 243–7. Bibcode:1947Sci...105..243A. doi:10.1126/science.105.2723.243.

- ↑ Brown, J. R.; Thornton, J. L. (1957). "Percivall Pott (1714-1788) and Chimney Sweepers' Cancer of the Scrotum". British journal of industrial medicine. 14 (1): 68–70. doi:10.1136/oem.14.1.68. PMC 1037746

. PMID 13396156.

. PMID 13396156. - ↑ Yamagawa K, Ichikawa K (1915). "Experimentelle Studie ueber die Pathogenese der Epithel geschwuelste". Mitteilungen aus der medizinischen Fakultät der Kaiserlichen Universität zu Tokyo. 15: 295–344.

- ↑ Luch, Andreas (2005). "Nature and Nurture — Lessons from Chemical Carcinogenesis: Chemical Carcinogens — From Past to Present". Medscape.

- ↑ Boyland E (1950). "The biological significance of metabolism of polycyclic compounds". Biochemical Society Symposia. 5: 40–54. ISSN 0067-8694. OCLC 216723160.

- ↑ Omura, T.; Sato, R. (1962). "A new cytochrome in liver microsomes". The Journal of Biological Chemistry. 237: 1375–1376. PMID 14482007.

- ↑ Conney, A. H. (1982). "Induction of microsomal enzymes by foreign chemicals and carcinogenesis by polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons: G. H. A. Clowes Memorial Lecture". Cancer Research. 42 (12): 4875–4917. PMID 6814745.

- ↑ Wood RD (March 2013). "Human DNA Repair Genes". The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center.

- 1 2 Loeb, L. A. (1989). "Endogenous carcinogenesis: Molecular oncology into the twenty-first century--presidential address" (PDF). Cancer Research. 49 (20): 5489–5496. PMID 2676144.

- ↑ Trevor M. Penning (2011). Chemical Carcinogenesis (Current Cancer Research). Springer. ISBN 978-1617379949.

- ↑ Schaaper, R. M.; Glickman, B. W.; Loeb, L. A. (1982). "Role of depurination in mutagenesis by chemical carcinogens". Cancer Research. 42 (9): 3480–3485. PMID 6213293.

- ↑ Melendez-Colon, V. J.; Smith, C. A.; Seidel, A.; Luch, A.; Platt, K. L.; Baird, W. M. (1997). "Formation of stable adducts and absence of depurinating DNA adducts in cells and DNA treated with the potent carcinogen dibenzoa,lpyrene or its diol epoxides". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 94 (25): 13542–13547. doi:10.1073/pnas.94.25.13542. PMC 28342

. PMID 9391062.

. PMID 9391062. - ↑ Boysen, G.; Pachkowski, B. F.; Nakamura, J.; Swenberg, J. A. (2009). "The Formation and Biological Significance of N7-Guanine Adducts". Mutation Research/Genetic Toxicology and Environmental Mutagenesis. 678 (2): 76–94. doi:10.1016/j.mrgentox.2009.05.006. PMC 2739241

. PMID 19465146.

. PMID 19465146. - ↑ Loechler, E. L. (1996). "The role of adduct site-specific mutagenesis in understanding how carcinogen-DNA adducts cause mutations: Perspective, prospects and problems". Carcinogenesis. 17 (5): 895–902. doi:10.1093/carcin/17.5.895. PMID 8640935.

- ↑ Bernstein, H; Bernstein, C (2013). "Evolutionary Origin and Adaptive Function of Meiosis". In Bernstein, Carol. Meiosis. InTech. ISBN 978-953-51-1197-9.

- ↑ Sakai A, Nakanishi M, Yoshiyama K, Maki H (July 2006). "Impact of reactive oxygen species on spontaneous mutagenesis in Escherichia coli". Genes Cells. 11 (7): 767–78. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2443.2006.00982.x. PMID 16824196.

- ↑ Kunz BA, Ramachandran K, Vonarx EJ (April 1998). "DNA sequence analysis of spontaneous mutagenesis in Saccharomyces cerevisiae". Genetics. 148 (4): 1491–505. PMC 1460101

. PMID 9560369.

. PMID 9560369. - ↑ Huertas P (January 2010). "DNA resection in eukaryotes: deciding how to fix the break". Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17 (1): 11–6. doi:10.1038/nsmb.1710. PMC 2850169

. PMID 20051983.

. PMID 20051983. - ↑ Setlow, R. B. (1966). "Cyclobutane-type pyrimidine dimers in polynucleotides". Science. 153 (734): 379–386. doi:10.1126/science.153.3734.379. PMID 5328566.

- ↑ Broyde, S.; Patel, D. J. (2010). "DNA repair: How to accurately bypass damage". Nature. 465 (7301): 1023–1024. doi:10.1038/4651023a. PMID 20577203.

- ↑ Salnikow K1, Zhitkovich (January 2008). "Genetic and epigenetic mechanisms in metal carcinogenesis and cocarcinogenesis: nickel, arsenic, and chromium". A. Chem Res Toxicol. 21 (1): 28–44. PMID 24188101.

| Look up mutagenesis in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |